Often known as “needlepoint lace,” needle lace is a term referring to the technique in which the lace is made of entirely needle work; it developed in the 15th century and then became very popular throughout the 16th century.

The Details

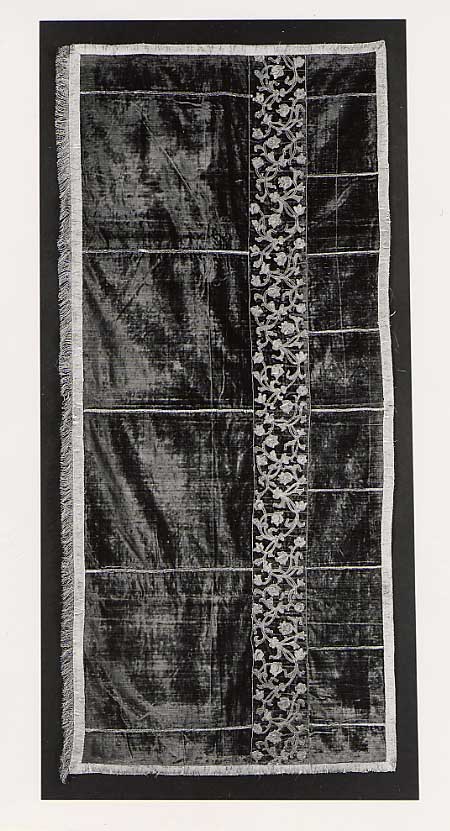

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has a strip (Fig. 1) of early needle lace from the 16th century. This is one style of early lace, as Melinda Watt explains:

“There are essentially two methods of making lace: both involve the manipulation of fine linen thread and they are commonly referred to by the names of the tools used. Needle lace requires the use of a single thread and a needle to make stitches one after another which gradually build up a fabric. Bobbin lace uses many threads attached to small bobbins, which are interwoven in various combinations to create a pattern.”

The Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion explains the original meaning of lace was quite different:

“Before needle and bobbin lace developed in the sixteenth century, the term lace referred to the cords that laced separate parts of a garment together, such as the sleeves to the shoulders, or to close the back of a bodice. The cords were made in a variety of methods, including the use of bobbins to braid the threads. The term also referred to braided tapes of metallic thread that often trimmed military uniforms. This use of the word ‘lace’ in this context continued into the eighteenth century, when it also described the woven bands that trimmed servant’s livery and the furnishings found in coaches and other vehicles.“

Watt explains further: “Fashions in lace change markedly during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, from simple geometric edgings of the early seventeenth century, to the Baroque three-dimensional needle lace of the second half of the seventeenth century, to the airy decorated net of the late eighteenth century.”

‘Needle-point lace’ is often interchanged with ‘needle lace.’ Mary Brooks Picken defines ‘needle-point lace’ in The Fashion Dictionary as:

“Lace that is made entirely with a sewing needle rather than bobbins. Worked with buttonhole- and blanket stitches on paper pattern.” (222)

Fig. 1 - Maker unknown (Italian). Strip, 16th century. Needle lace; 27.9 x 6.4 cm (11 x 2.5 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 79.1.139. Anonymous Gift, 1879. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - Maker unknown (Italian). Antependium, 15th century (antependium) and 16th century or 17th century (border). Silk and metal; 106 x 239.4 cm (41 3/4 x 94 1/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.1.1904. Robert Lehman Collection 1975. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Portrait of Claude of France (1547–1575) Duchess of Lorraine, circa 1565. Oil on panel; 32 × 25 cm (12.6 × 9.8 in). Versailles: Palace of Versailles, RF 1973 30. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 4 - Maker unknown (British). Smock, 1603-1610. Linen. London: Museum of London, 28.83. Source: Museum of London

Fig. 5 - Maker unknown (British). Detail of Smock, 1603-1610. Linen. London: Museum of London, 28.83. Source: Museum of London

“In the painting of Claude, Duchess of Lorraine, needle laces begin to appear, bridging the gap between incidental clothes-decoration and the headier world of fashion; and it was needle laces which first established themselves for Court wear rather than bobbin laces which for a while longer remained simple and ‘lower class’.” (12)

In a women’s smock made circa 1603-1610, you can see examples of both lace techniques (Figs. 4 & 5), as the Museum of London notes:

“Two narrow (15mm) bands of geometric needle lace worked in a plaited thread base are inset 30 and 100mm above the hem. Scallops of freely worked needle lace decorate the hem, the cuffs, the front neck opening and the collar.”

This portrait of Claude (Fig. 6) shows many styles and fashion trends that were prevalent in the 16th century, including the intricate lace ruff, likely of the needle lace technique.

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown. Portrait of Claude of Valois (1547-1575) Duchess of Lorraine, 16th century. Oil on panel. Florence: Uffizi Gallery. Source: Wikimedia

Its Afterlife

References:

- Earnshaw, Pat. Lace in Fashion: From the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries, 2nd ed. Guildford: Gorse, 1991.

- “Needle lace”. Wikipedia. Accessed October 3, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Needle_lace

- Parmal, Pamela A. “Lace.” Gale Virtual Reference Library – Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion. Vol. 2. Detroit: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2005. Accessed October 3, 2016. http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&sw=w&u=fitsuny&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CCX3427500351&asid=da28c3d2a5d4cce357a7e60d7717009a.

- Picken, Mary Brooks. The Fashion Dictionary. Rev. ed. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1973.

- “Smock”. Museum of London. Accessed October 7, 2016. http://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/79205.html

- Tortora, Phyllis G. The Fairchild Books Dictionary of Fashion. 4th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2014.

- Watt, Melinda. “Textile Production in Europe: Lace, 1600–1800.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. October 2003/Accessed October 3, 2016. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/txt_l/hd_txt_l.htm