Christian Dior’s Eugénie ball gown drew on a nineteenth-century empress for inspiration and injected lighthearted, modern flair to create a fierce, feminine gown for a collection that contributed to the survival of French haute couture.

About the Look

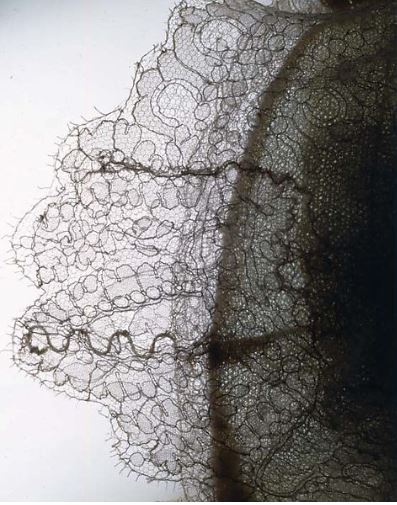

Christian Dior designed the Eugénie ball gown for his 1948 Fall/Winter collection, Zig Zag. The dress, made from blush-pink nylon, was photographed by Willy Maywald in 1948 (Fig. 1) and is full of intricate details. The silhouette has a tiered bell-shaped skirt with a hem that lengthens towards the back in what is called the ailée line. Dior used layers of tulle to create a cascading effect on the skirt. It has a fitted sleeveless bodice with boning to maintain a smooth silhouette at the top with a tight waist. There are lace details (Fig. 2) along the sweetheart neckline kept in place with wire stays, so that even elements of the dress that appear to be light and soft are kept securely in place. By installing a heavy-duty understructure, Dior has created a clear silhouette while staying true to an airy and feminine effect with lacy sheerness throughout the skirt.

Fig. 1 - Willy Maywald (German, 1907-1985). Eugénie dress, Fall/Winter 1948. Photograph. Source: L'Officiel Mexico

Fig. 2 - Christian Dior (French, 1905-1957). "Eugénie" dress lace detail, Fall/Winter 1948-49. Nylon, wire. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.53.40.2a–c. Source: The Met

Christian Dior (French, 1905-1957). Eugénie, Fall/Winter 1948-49. Nylon and leather. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.53.40.2a–c. Gift of Mrs. Byron C. Foy. Source: The Met

About the context

In 1947, Christian Dior established his own maison de la couture with a collection that contributed to the revival of haute couture in France after World War II. Katie Somerville quotes Dior in The House of Dior: Seventy Years of Haute Couture (2017):

“I designed clothes for flower-like women, with rounded shoulders, full, feminine busts, and hand-span waists above enormous, spreading skirts.” (115)

His collections captivated public attention with his creation of new silhouettes and use of extravagant amounts of fabric (Fig. 3), which had been rationed during the war. He debuted what was subsequently deemed by the press as his “New Look” c0llection in 1947, featuring large skirts and small waists, and the 1948 collections continued in that same vein. After women took on many working roles during the war, a rejuvenation of femininity was celebrated – and sometimes protested – with the New Look, and it was not limited to couture. An ad for the Minnesota department store Stix, Baer, & Fuller calls the silhouette of a Nettie Rosenstein gown “the charm of complete femininity raised to new heights” (69). The Rosenstein dress seen in figure 4 dates to 1947 and displays her version of the New Look.

The New Look took inspiration from the crinoline styles of the mid-nineteenth century; Eugénie draws a direct comparison to not only crinoline fashions but the woman most famous in France for contributing to the rise of haute couture itself: Empress Eugénie de Montijo, wife of Napoléon III of France. Eugénie includes lighthearted and feminine Second Empire elements to create a frothy gown.

In Fashion in the Forties & Fifties (1975), Jane Dorner describes how “this ultra-feminine style reminded people of the Empress Eugenie, one of the most influential patrons of French couture in the 1850s” (27). From the 1860s onward, the Empress frequently wore the creations of Charles Frederick Worth, who is often credited as the founder of haute couture. Dior was also inspired by Franz Winterhalter’s romantic paintings of the the Empress’ court (Fig. 5), and from there attached her name to the gown.

A fashion journalist who attended Dior’s Paris Zig Zag opening wrote in a February 19th, 1948 column for Women’s Wear Daily titled “Dior Silhouette Acclaimed Again, Combining Slim, Stiffened Lines,” that “Despite gowns of limitless yardage, and rich costume jewelry and embroideries, the general impression is modern and wearable.”

Dior was perfectly on-trend for the fashions of 1948; in fact, he was helping set the trends. An article entitled “The Big News from Paris” in the October 1948 issue of Harper’s Bazaar described the range in skirts:

“The big news is movement. Movement in skirts that plunge down at one side or swoop out behind… Dior calls his backswept skirts and jacket ailé, or winged. They have tremendous vitality.

The big news is skirt interest, stressed at every house in Paris. Bodices are simple. Skirts swirl, or dip in exciting, irregular lines… Many are beautifully shirred – Jacques Fath, Balenciaga, Dior all break the surface of the skirts of black dresses with rich, bumpy shirring. Skirt interest is often between knee and hemline; shirring or stiffening are reserved for the bottom of the skirt.” (29).

A similar kind of visual interest can be seen in figure 6, Diamant Noir, a cocktail dress from the same F/W 1948 collection by Dior. Many of the dresses in Zig Zag featured shirring or ruffling as details (Fig. 7), and the trend carried over into the work of designers like Balmain, whose dress in figure 8 is from 1949 and shows clear influence of Dior’s Eugénie.

Through photography, Dior visually emphasizes the delicate yet alluring essence of the Eugénie gown. Through the positioning of the models, the audience’s attention is brought towards the full circumference of the gown’s sweeping bell shape and tight waistline, as exemplified in figure 1. Other photos took Winterhalter’s painting as inspiration, bringing the gown into the modern age with an air of relaxation (Fig. 9). Dior places clear emphasis on the revival of conventional, historical feminine styles with an enticing zig-zag twist that restores fantasy to a modern world.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art describes the Zig Zag collection as:

“a series of gowns that advanced the exquisite opulence of this prophetic New Look… Each [dress] exploited the lavish drapery and controlled tailoring of Dior’s New Look, but with novel emphasis on asymmetry that was to become a Dior leitmotif.” (Met)

Daniel James Cole and Nancy Deihl note in The History of Modern Fashion (2015) that “Harper’s Bazaar declared him ‘agent provocateur and hero of the day'” (209). In the creation of Eugénie, Dior did not simply copy the past: he expanded upon the designs of his predecessors to create a modern look of femininity for the new age. His willingness and courage to take risks lead to the reemergence of French haute couture and gave Dior a dominant voice in the world of fashion.

Fig. 3 - Christian Dior (French, 1905-1957). Junon, Fall/Winter 1949-50. Silk, plastic. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.53.40.5a–e. Gift of Mrs. Byron C. Foy, 1953. Source: The Met

Fig. 4 - Nettie Rosenstein (American, 1890-1980). Dress, 1947. Silk / wool faille and horsehair. New York: Museum at FIT, 74.135.8. Gift of Janet Chatfield-Taylor. Source: MFIT

Fig. 5 - Franz Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). The Empress Eugénie Surrounded by her Ladies-in-Waiting, 1855. Oil on canvas; 402 x 300 cm. Château de Compiègne, MMPO 941. Source: Château de Compiègne

Fig. 6 - Christian Dior (French, 1905-1957). Diamant Noir, Fall/Winter 1948. Silk, cotton. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997.331.2a, b. Gift of Helen Marshall Scholz, 1997. Source: The Met

Fig. 7 - Christian Dior (French, 1905-1957). Tourterelle, Fall/Winter 1948. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.176.2a, b. Gift of Mrs. Pierre David-Weill, 1975. Source: The Met

Fig. 8 - Pierre Balmain (French, 1914-1982). Evening dress, 1949. Pink and off-white satin, off-white net, taffeta, and feathers. New York: Museum at FIT, 91.244.1. Gift of Barbara Louis. Source: MFIT

Fig. 9 - Willy Maywald (German, 1907-1985). A model wears the Eugenie dress, Fall/Winter 1948. Photograph. National Gallery of Victoria. Source: ABC

References:

- “Advertisement: (Stix, Baer & Fuller).” Harper’s Bazaar 82, no. 2842 (10, 1948): 69. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1799794473?accountid=27253

- “The Big News from Paris.” Harper’s Bazaar 40, no. 1 (October 1948): 10, 27-29, 82, 30-36. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1920625446?accountid=27253

- Cole, Daniel James, and Nancy Deihl. The History of Modern Fashion from 1850. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/900012311

- “Dior Silhouette Acclaimed Again, Combining Slim, Stiffened Lines: Large Collection Stresses Ensembles Complete with Hats, Shoes and Accessories—”Zig Zag” and “En Vol” Featured Silhouettes — Belted “Nonchalant” Coat Lines Cited.” Women’s Wear Daily (Feb 9, 1948): 3. ProQuest. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1627552720?accountid=27253

- Dorner, Jane. Fashion in the Forties & Fifties. New Rochelle: Arlington House Publishers, 1975. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/2931035

- “Eventail (Fan).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed 6 June 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/128071

- Somerville, Katie, Lydia Kamitsis, and Danielle Whitfield. The House of Dior: Seventy Years of Haute Couture. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1005133722