OVERVIEW

The 1760s mark the last decade during which the robe à la française dominated women’s wardrobes since it was first introduced in the 1720s. In the last three decades of the eighteenth century, other, more informal styles became fashionable for daywear and the robe à la française was increasingly worn for evening. For men, the distinction between the subdued informality of Englishmen’s dress and the colorful formality of Continental styles (particularly those of France and Italy) remained pronounced, although this would change in the following decades in favor of the former. The narrowing of the coat that began around 1750 continued in this decade and a low standing collar that would increase in height until the end of the century appeared in the middle years.

Womenswear

Thomas Gainsborough’s full-length 1764 portrait of Mary, Countess Howe (Fig. 1), conveys the understated elegance favored by aristocratic English women for daywear. The countess wears a pale pink silk taffeta “nightgown” (a style of dress with a fitted back that was popular in England from the early eighteenth century) with oval sleeve cuffs decorated with bows and a matching petticoat with a single flounce. The gently rounded skirts suggest that she has adopted a newly fashionable small hoop or side hoops. The lightweight silk, known as “lutestring” during the period, was favored for informal summer wear (Ribeiro/Earl and Countess Howe 32). Her “arsenal of accessories” includes a wide-brimmed straw hat decorated with white satin ribbons, a multi-strand pearl choker and large circular pearl earrings, lace sleeve ruffles, or engageantes, a sheer fichu and apron (either fine embroidered mull or gauze), black silk “bracelets,” and high-heeled black leather buckled shoes (Ribeiro/Earl and Countess Howe 32). Although Gainsborough placed Countess Howe in a landscape setting as though he had come upon her out for a walk in the countryside around Bath, the portrait was painted in his studio in that spa town, where the countess’s husband was taking the waters for his gout. As dress historian Aileen Ribeiro observes (Ribeiro/Earl and Countess Howe 33):

“Gainsborough’s portrait of Lady Howe is apt testimony to the art of graceful deportment; it is almost as though she has been captured on canvas, poised to take the next step in a formal dance.”

In the eighteenth century, clothes themselves–especially the corset (Fig. 2) and pannier for women–that gently or otherwise encouraged ideal posture worked together with proper bearing, inculcated from childhood with lessons from the dancing master, to communicate social standing and a life of leisure.

Fig. 1 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727-1788). Portrait of Mary, Countess of Howe, 1764. Oil on canvas; 244 x 152.4 cm. London: Kenwood House, 88028783. Source: MFAH

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French). Corset, ca. 1760s. Silk, linen, leather, wood, baleen. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.50.8.2. Gift of Mrs. William Martine Weaver, 1950. Source: The Met

Fig. 3 - Joseph Wright of Derby (British, 1734-1797). Peter Perez Burdett and his First Wife Hannah, 1765. Oil on canvas; 145 x 205 cm. Prague: National Gallery Prague, DO 4289. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (British). Mitts, ca late 18th century. Leather, silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.6196a, b. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Met

The difference between men’s and women’s clothing during this decade that was especially pronounced in England is evident in Joseph Wright of Derby’s 1765 portrait of Peter Perez Burdett and his first wife Hannah Burdett (Fig. 3). In contrast to her husband’s informal clothing that was eminently suitable for the Derbyshire landscape in which they are portrayed and which he was in the process of surveying, Hannah Burdett (a wealthy widow at the time of her marriage) selected a cream silk sack trimmed with scrolling self-fabric along the center front edges, a pale lavender taffeta petticoat with a scalloped flounce, a stomacher with ribbon bows known in French as an echelle, pearl choker and earrings, a luxurious white silk satin fichu edged with blonde (silk) lace and matching triple engageantes (Egerton 87-88). On her right hand, she wears a mitt, probably of kid, and, around her left wrist, a hardstone bracelet (Fig. 4). While her cartographer husband holds a telescope, Mrs. Burdett’s concession to the out-of-doors setting is the “small branch of may, or hawthorn” in her right hand (Egerton 87).

Fig. 5 - Allan Ramsay II (British, 1713-1784). Anne (Archer) Garth-Turnour, Baroness (later Countess) Winterton, 1762. Oil on canvas; 75.6 x 63.5 cm. San Marino: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, 58.20. Source: The Huntington

Fig. 6 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727–1788). Mary Little, later Lady Carr, 1765. Oil on canvas; 127 x 101.6 cm. B1987.6.2. Bequest of Mrs. Harry Payne Bingham. Source: Yale Center For British Art

Fig. 7 - Anton Raphael Mengs (German, 1728–1779). Maria Amalia of Saxony, ca. 1761. Oil on canvas; 153.2 x 110.2 cm. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, P002201. Source: Museo Nacional del Prado

Fig. 8 - Alexander Roslin (Swedish, 1718-1793). Mme Adelaïde, daughter of Louis XV, 1765. Oil on canvas. Mora: Zorn Collections, ZKO 236. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 9 - Pompeo Batoni (Italian, 1708-1787). Portrait of Lady Margaret Georgiana Poyntz, ca. 1764. Oil on canvas. Northampton: Althorp. Source: Wikimedia

Women of fashion kept up with subtle changes in appearance. In the winter of 1765-66, Lady Sarah Bunbury (née Lennox) shared important advice with her niece, Susan Fox-Strangways:

“To be perfectly genteel you must be dressed thus… The roots of the hair must be drawn up straight and not fruzed at all for half an inch above the roots; you must wear no cap and only little, little flowers dab’d in on the left side; the only feather permitted is a black or white sultane perched up on the left side and your diamond feather against it. A broad puffed ribbon collier [necklace] with a tippet ruff or only a little black handkerchief very narrow over the shoulders; your stays very high and pretty tight at the bottom; your gown trimmed… the sleeves long and loose, the waist very long, the flounces and ruffles of a decent length, not too long nor so hideously short as they now wear them. No trimming on the sleeve, but a ribbon knot tied to hang on the ruffles.” (quoted in Tillyard 157)

After providing these numerous details regarding female attire, Sarah indicated that “the men’s dress is exactly what they used to wear latterly” (quoted in Tillyard 157).

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (British). Dress, ca. 1760. Silk, linen, cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996.374a–c. Purchase, Arlene Cooper and Polaire Weissman Funds, 1996. Source: The Met

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (British). Sack, ca. 1760 - 1765. Silk, linen, silk thread, linen thread. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.77 to B-1959. Given by John Sterling Williams. Source: V&A

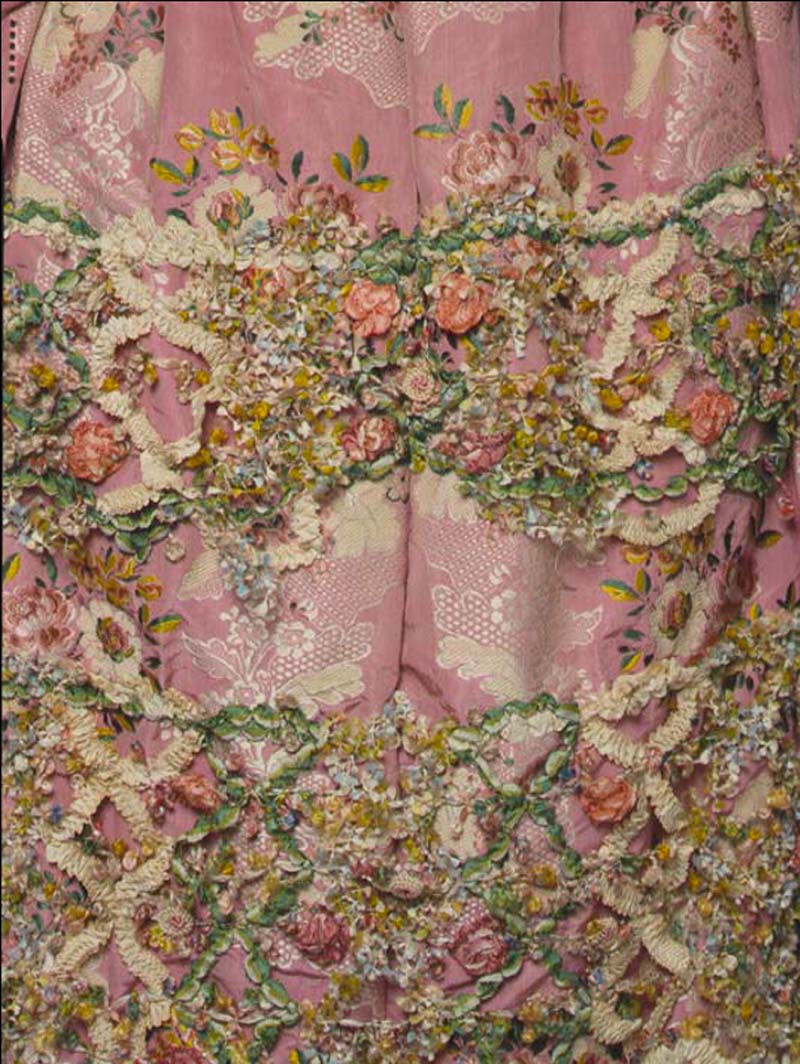

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à la Française, ca. 1750-75. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.59.29.1a, b. Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1959. Source: The Met

Although women’s shoes and stockings were partially obscured by their gowns and petticoats, these accessories were important components of an ensemble and, for wealthy consumers, luxury items in their wardrobes (Fig. 14). Until the end of the century when kid became fashionable, woven or embroidered silks were used for female footwear, reinforcing the gender distinction between these delicate accessories and the sturdy leather of men’s shoes (Fig. 15). And, while a well-shaped calf was an asset for a man and shown to advantage by a smooth white silk stocking, the concealment of women’s legs and hosiery ensured their erotic appeal. Emily, Marchioness of Kildare and future Duchess of Leinster (née Lennox), was particularly fond of clocked stockings (Fig. 16) and her adoring husband purchased these in quantity on visits to London from their home in Ireland to compliment her “dear, pretty legs” (quoted in Tillyard 61). In the English capital in 1762, he informed her excitedly:

“I find I exceed your commission in regard to your stockings with coloured clocks. I bespoke two pairs with bright blue, two pairs with green and two pairs with pink coloured clocks. I am sure when you have them on, your dear legs will set them off. I will bespoke you six more pairs with white clocks; you mean to have them embroidered I suppose, therefore I shall make you a present of the dozen. The writing about your stockings and dear, pretty legs makes me feel what is not to be expressed.” (quoted in Tillyard 61)

Fig. 13 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à la française, ca. 1750-75. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.59.29.1a, b. Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1959. Source: The Met

Fig. 14 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727-1788). Ann Ford (later Mrs. Philip Thicknesse), 1760. Oil on canvas; 197.2 x 134.9 cm. Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 1927.396. Bequest of Mary M. Emery 1927. Source: CAM

Fig. 15 - Designer unknown (British). Pair of shoes, ca. 1760-70. Silk woven with metal thread; 13.5 x 7.8 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.462-1913. Given by Messrs Harrods Ltd.. Source: V&A

Fig. 16 - Designer unknown (European). Pair of Stockings, ca. 1750-1775. Silk; 72 x 15 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.34&A-1969. Source: V&A

Maternity wear as we know it today did not exist in the eighteenth century; instead, women adapted their existing garments. They did, however, substitute sleeveless (often quilted) waistcoats for their rigidly boned corsets, and these comfortable undergarments themselves, worn in the privacy of the home, were adapted for a rounded belly. An example with side lacings (Fig. 17) dating to the mid-eighteenth century may well have been worn by an expectant mother. The front of this waistcoat is made from taupe silk and edged with a matching ribbon, while the sides and back are of brown linen, “indicating that [it] was likely worn underneath a gown or perhaps a sleeved jacket bodice” (Cora Ginsburg 19). Allan Ramsay’s 1765 portrait of the Marchioness of Kildare was done during one of her multiple pregnancies (Fig. 18). The artist depicted her dressed in a pink silk sack accessorized with a black silk lace fichu and triple white sleeve ruffles and seated at a small table, reading, to hide her “condition.”

Fig. 17 - Michael Fredericks (Photographer) (French). Woman's Waistcoat, ca. 1730–1780. Silk, linen; 53.34 × 53.34 cm. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2011.667. Barbara E. and Richard J. Franke Fund. Source: Cora Ginsburg Catalogue

Fig. 18 - Allan Ramsay (Scottish, 1713-1784). Emily Countess of Kildare, 1765. Oil on canvas. Liverpool: Walker Art Gallery, 1356. Purchased 1951. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 19 - Johann Georg Ziesenis (German-Danish, 1716–1776). Princess Philippine Charlotte of Prussia, Duchess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, ca. 1760. Oil on canvas; 147.5 x 96.5 cm. Guildford: National Trust, Hatchlands, 1166728. Transferred by HM Treasury, 1958. Source: Art UK

Fig. 20 - Designer unknown (British). Quilted Petticoat, ca. 1760-1780. Silk. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 133-1900. Source: V&A

Fig. 21 - Joshua Reynolds (British, 1723-1792). Miss Nelly O'Brien, ca. 1762 - 1763. Oil on canvas; 126.3 x 101 cm. London: The Wallace Collection, P38. Source: WC

In the winter months, English women favored quilted petticoats that provided insulation in houses that relied on fireplaces to heat the rooms. An example in the Victoria & Albert Museum (Fig. 20) is typical of these practical yet decorative garments; the top fabric is silk satin, the lining is glazed wool, and the batting is also wool. Quilted petticoats were among the first ready-made clothing items for women, available since the late seventeenth century (Lemire 65). Although manufacturers had to keep abreast of current fashionable colors and quilting patterns, the perennial popularity of these garments ensured regular demand (Lemire 65). They did not require custom fitting since the tapes at the waistband could be tied to accommodate the individual wearer, or other fastenings such as hooks and eyes could be added later as necessary, and “the dimensions of the petticoat were less related to the size of the wearer than to the width of the hoops or number of underpetticoats employed” (Lemire 65).

Characterized by “uniformity and regularity,” ready-made petticoats that ranged in price and quality were made on quilting frames either by a seamstress at home or in a warehouse (Lemire 66). The large expanse of plain silk taffeta or satin (ivory, pink, blue, yellow, and green were favorite colors) provided an ideal surface for decorative display at the front opening of a woman’s gown. Sir Joshua Reynolds’s portrait of Nelly O’Brien dating about 1762-1763 shows the celebrated beauty and courtesan in a blue-and-white striped silk gown and pink silk petticoat quilted in an all-over diamond pattern over which she wears an almost transparent delicately floral-patterned apron (Figs. 21, 22). The petticoat’s subtle color compliments O’Brien’s (rouged) cheeks that set off the paleness of her skin (which was the fashionable ideal for women at the time) and creamy pearl choker.

Fig. 22 - Designer unknown (British). Apron, ca. 1760. Silk gauze; 91.44 x 114.3 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.196-1959. Bequeathed by Miss M. S. Mourilyan. Source: V&A

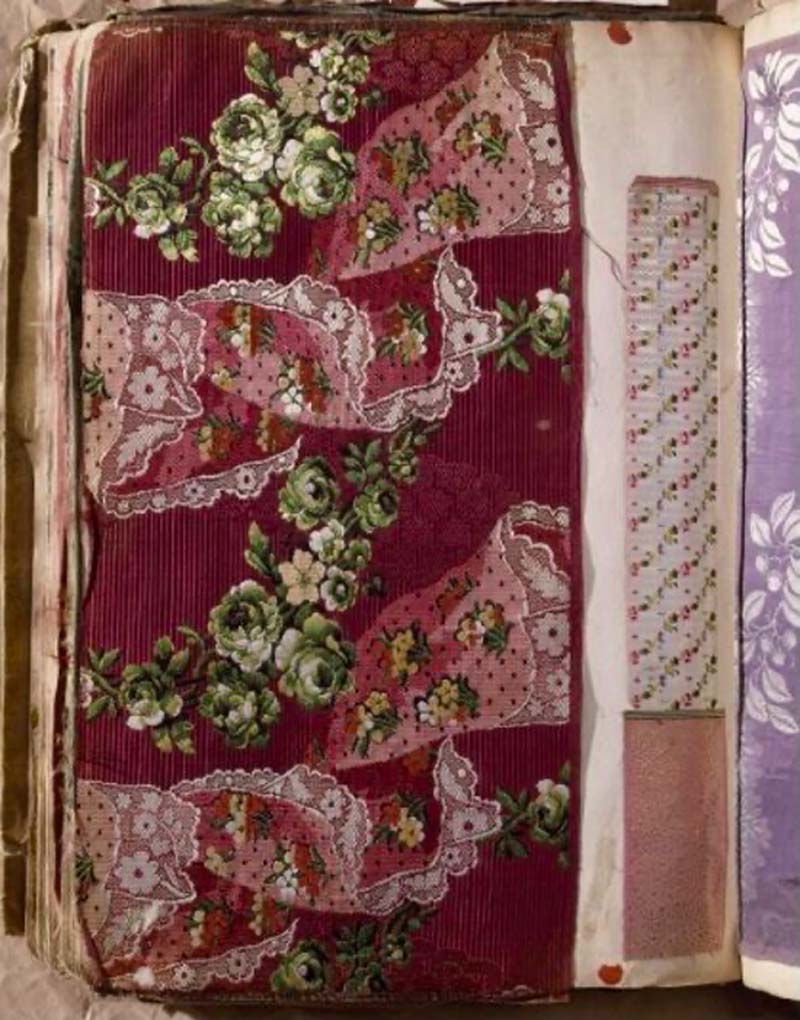

Fig. 23 - Artist unknown (French). Swatch Book, 1764. Silk, taffeta, linen, brocaded, leather bound, paper and ink, sealing wax; 53.97 x 39.37 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.373-1972. Acquired with the help of Marks and Spencer Ltd and the Worshipful Company of Weavers. Source: V&A

Fig. 24 - Artist unknown (French). Swatch Book, 1764. Silk, taffeta, linen, brocaded, leather bound, paper and ink, sealing wax; 53.97 x 39.37 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.373-1972. Acquired with the help of Marks and Spencer Ltd and the Worshipful Company of Weavers. Source: V&A

Fig. 25 - Designer unknown (French). Sack, ca. 1765-1770. Silk, lace; 156 x 26 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.708&A-1913. Given by Messrs Harrods Ltd.. Source: V&A

A French sample book dating to 1764 in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum (Figs. 23-24) shows the wide range of designs, weaves, and palettes that were fashionable in the middle years of the decade. At the high end are the brocaded silks with complex weave structures featuring what are now referred to as “meander patterns” in which undulating bands of ribbons, lace, faux fur, feathers, and other motifs interspersed with floral bouquets create a strong vertical emphasis (Fig. 23). The rich textural effect of these heavy silks—“a tour de force of the weaver’s art”—is enhanced by the amount and variety of threads including silk, metal, and chenille and their figured grounds (Rothstein 53). Taffetas with shaded stripes, floral-sprigged striped satins, and chiné (warp-dyed) taffetas also appear in this merchant’s sample album (Fig. 24). The widespread popularity of these silks is confirmed in both portraiture and surviving garments (Figs. 25-29).

Fig. 26 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à la française, ca. 1765. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 38.30.1a, b. Fletcher Fund, 1938. Source: The Met

Fig. 27 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à la française, ca. 1765. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 38.30.1a, b. Fletcher Fund, 1938. Source: The Met

Fig. 28 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à la française, ca. 1760–70. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.60.40.2a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1960. Source: The Met

Fig. 29 - Tibout Regters (Dutch, 1710-1768). Portrait of a Woman, 1743. Oil on copper; 15.3 x 12.7 cm. Private Collection. Source: Wikimedia

European printed cottons and woven silks as well as Chinese painted silks attested to the continuing vogue for chinoiserie in the 1760s. The “imaginary flowering branches [on] the creamy surface” of an informal French block-printed robe à la française (Fig. 30) “exemplify the spirit of Orientalist fantasy and its perfect adaptation to Rococo taste in French fashion” (Stewart 212). The exotic motifs show the influence of the French artist Jean-Baptiste Pillement (1728-1808), who created numerous designs that were subsequently engraved and used on porcelain, wallpaper, textiles, and silver. His publications including A New Book of Chinese Ornament of 1755 aided in the dissemination of these finely drawn and often whimsical images (Stewart 213). On a French formal gown brocaded with silk and metal thread, the diminutive pagodas are barely visible among the larger floral-and-foliate sprays and gold stripes entwined with floral sprigs (Figs. 31, 32). Chinese painted silks, commissioned for Western consumers, featured colorful exotic flowers on sinuous stems against white or pale-colored taffeta or satin grounds (Fig. 33)

Fig. 30 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à la française, ca. 1760s. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.64.32.3a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1964. Source: The Met

Fig. 31 - Designer unknown (French). Dress, ca. 1760s. Silk, metal thread. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 50.168.2a, b. Gift of Fédération de la Soirie, 1950. Source: The Met

Fig. 32 - Designer unknown (French). Dress, ca. 1760s. Silk, metal thread. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 50.168.2a, b. Gift of Fédération de la Soirie, 1950. Source: The Met

Fig. 33 - Designer unknown (British-Chinese). Sack, ca. 1735-1760. Painted silk, chenille. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.115&A-1953. Source: V&A

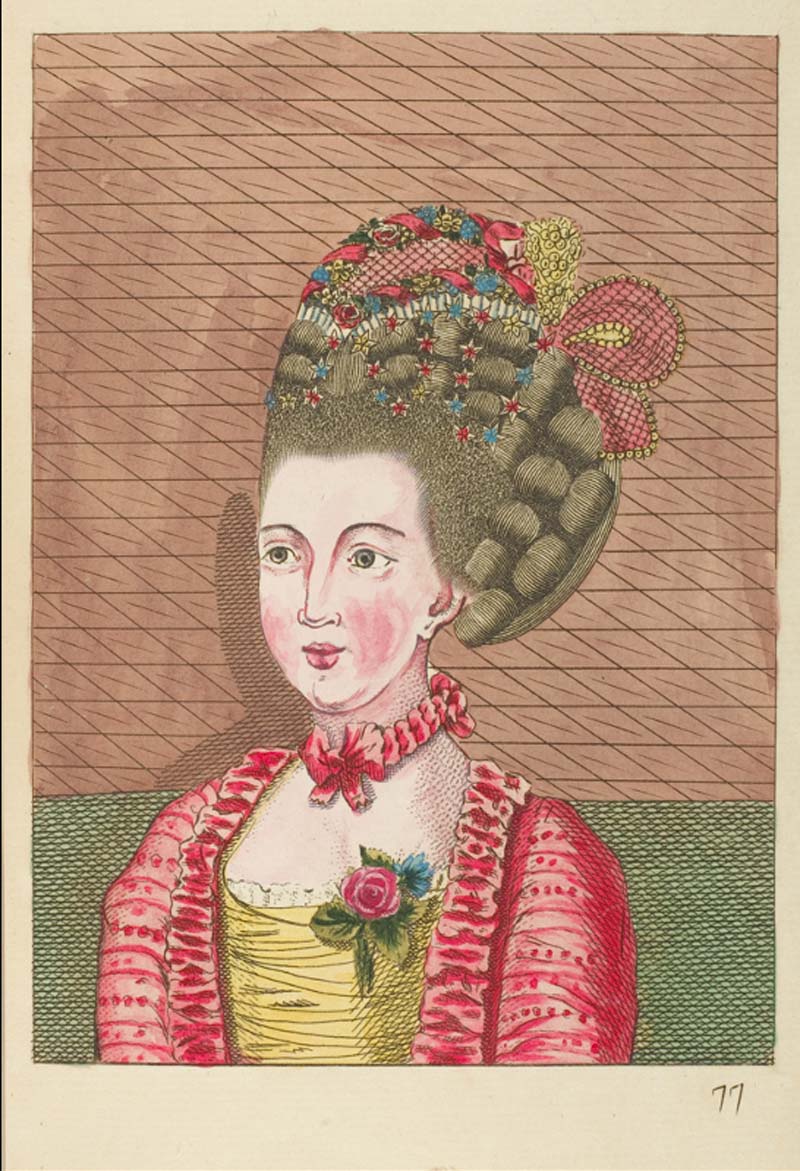

In the early 1760s, women’s hairstyles that had been curled closely to the head since the 1720s began to rise at the front of the crown and by the end of the decade, this increasing height that would reach its fullest vertical expression in the 1770s was already drawing disapproval. In 1763, the Ipswich Journal deplored this unfortunate trend: “Ladies of fashion…their heads are covered with a vast load of false hair which is frizzed on the forehead” (quoted in Cunnington 370). By the end of the decade in 1768, the Gentleman’s Magazine summed up these now more prominent arrangements that depended on a variety of supplementary materials for their construction and blamed their importation on the French:

“When he sees your tresses thin / Tortur’d by some French friseur, / Horsehair, hemp, and wool within, / Garnish’d with a diamond skewer; / When he scents the mingled steam / Which your plastered heads are rich in, / Lard and meal and clotted cream, / Can he love a walking kitchen?” (quoted in Cunnington 372)

L’Art de la Coëffure des Dames Françoises (Figs. 34, 35), a five-volume work with one hundred engraved plates published between 1768 and 1770 by Legros de Rumigny, a “cook-turned-coiffeur,” illustrates numerous examples of these upward-inclined hairstyles that—as their surface area increased—provided ample space for additional ornaments including “ribbons, lace, jewels, artificial flowers, [and] feathers” (Cora Ginsburg 18). Legros was coiffeur to well-placed clients, such as Madame de Pompadour and her successor as the king’s favorite, Madame du Barry, who excelled at self-promotion. In the text of his opus, Legros positions himself as the most talented among his peers and “cites the usefulness of his work for milliners as well as portrait painters, who would benefit from the study of his plates in order to accurately depict their sitters’ hair” (Cora Ginsburg 18). He founded the first hairdressing school, the Académie de Coëffure, which trained aspiring coiffeurs “as well as valets-de-chambre and ladies’ maids” and his publicity-seeking endeavors included hiring “models to walk along the Parisian ramparts, a fashionable promenading spot, and exhibiting dolls at one of the well-known city fairs” (Cora Ginsburg 18). Legros sold his own (undoubtedly superior) pomade that incorporated some of the “kitchen” ingredients satirized by the Gentleman’s Magazine: beef marrow, hazelnut oil, and essence of lemon. Similarly, the names of the complex arrangements of real and false hair in the plates were perhaps inspired by his former profession: “coque (egg) marron (chestnut) and bouillons (bubbles)” (Cora Ginsburg 18).

Fig. 34 - Legros de Rumigny (French, 1710-1770). L'art de la coëffure des dames françoises, avec des estampes, ca. 1768–70. Leather, paper. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.126a–e. Purchase, Friends of The Costume Institute Gifts, 2004. Source: The Met

Fig. 35 - Legros de Rumigny (French, 1710-1770). L'art de la coëffure des dames françoises, avec des estampes, ca. 1768–70. Leather, paper. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.126a–e. Purchase, Friends of The Costume Institute Gifts, 2004. Source: The Met

Fashion Icon: KITTY FISHER (CA. 1738-1767)

Fig. 1 - Sir Joshua Reynolds (British, 1723-1792). Catherine ‘Kitty’ Fisher, later Mrs Norris, 1759. Oil on canvas; 74.5 x 61.5 cm. West Sussex: National Trust, Petworth House, 486167. Source: National Trust

Fig. 2 - Joshua Reynolds (British, 1723-1792). Kitty Fisher as "Cleopatra" Dissolving the Pearl, 1759. Oil on canvas. London: Kenwood House, English Heritage. Iveagh Bequest, 1927. Source: MFAH

Fig. 3 - Allan Ramsay (Scottish, 1713-1784). Portrait of Lady Susan Fox-Strangways, 1761. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 4 - Nathaniel Hone (Irish, 1718-1784). Portrait of Kitty Fisher, 1765. Oil on canvas; 74.9 x 62.2 cm. London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2354. Bequeathed by John Baring, 2nd Baron Revelstoke, 1929. Source: NPG

In the eighteenth century, respectable society women did not draw attention to themselves through their behavior or their dress. Those whose names are familiar to us in the twenty-first century as trendsetters were often perceived as morally compromised. Marie Antoinette’s status as Queen of France did not protect her from vitriol and slander when it came to her pursuit of la mode; in fact, her attention to fashion was a liability that contributed directly to her downfall. Although courtesans’ propensity for ostentatious dress and jewels was condemned, for these women who made their living by being beautiful, fashion was integral to their success and an acknowledged part of their visibility and renown.

Fisher was one of Sir Joshua Reynolds’s favorite models at the time and, in 1759, she sat for two portraits by the celebrated painter. One of these depicts her in pearls, a black silk fichu, and outsized lace engageantes that trail over the edges of the table at which she is seated (Fig. 1). The other shows her as Cleopatra in a scene that “recalls [the Egyptian queen] impressing Mark Antony by dropping a pearl into a glass of wine and drinking it at their first banquet” (Conway 36) (Fig. 2). Literary and cultural historian Alison Conway notes that this painting aptly comments “on Kitty Fisher’s status as a courtesan” since it evokes an incident in which she was said to have ingested a L50 banknote as dismissive gesture to one of her admirers, the Duke of York (Conway 36-37). Conway further suggests that:

“Reynolds was willing to translate Kitty Fisher’s status as a courtesan into an aesthetic and material opportunity for himself, to respond to a popular demand for scandalous images.” (Conway 36)

Both 1759 portraits of Fisher were engraved and widely disseminated, enhancing the reputations of both artist and sitter.

Susan Fox-Strangways, the recipient of fashion advice from her aunt Sarah, was one of many young women at the time who were:

“fascinated with the theatre and the personal power that actresses and courtesans like Kitty Fisher occasionally attained [and] copied her eagerly.” (Tillyard 139)

Another of Fox-Strangways’s female relatives referred to Fisher’s “extravagant dress and manner” as “the Kitty Fisher style” (quoted in Tillyard 139). Nonetheless, Fox-Strangways would emulate Fisher’s pose in Reynolds’s 1759 painting (Fig. 1) when she sat for her own portrayal by Allan Ramsay in 1761 (Fig. 3). Fox-Strangways’s portrait would join those of other members of her illustrious family in the picture gallery at Holland House, London.

Nathaniel Hone’s 1765 portrait of Fisher (Fig. 4) uses a rebus, “a common semiotic tool in eighteenth-century prints,” as a play on the courtesan’s name and as “a kind of ‘doubling’, representing the woman as the subject of the painting, and… by representing her emblematically in a way which says something about her character and her position” (Thom). Draped in gauzy gold-embroidered fabric, Fisher wears a delicate choker and multi-strand pearl bracelet. To her left is a cat dipping its paw into a large goldfish bowl—literally “a fishing cat, or indeed a kitty fisher.” The cat, however, can be interpreted as “representative of Fisher herself, the playful, feminine and kittenish courtesan; but also as a predator” (Thom). Visible for all to see through the glass, the “goldfish, like celebrated ‘women of the town’, are shimmering, ephemeral, and easily replaceable” (Thom). Thus, at the same time that Hone’s portrait promotes Fisher’s beauty and celebrity, it also comments on the courtesan’s vulnerability that, in her case, was her death at age 29.

Menswear

Although many young Englishmen who undertook the Grand Tour commissioned portraits of themselves while abroad in the luxurious silks and velvets worn on the Continent, the four sitters in Nathaniel Dance Holland’s group portrait, A Conversation Piece in Rome: James Grant, Mr. Mytton, The Hon. Thomas Robinson, and Mr. Wynne (Fig. 3), preferred to be recorded in their distinctly understated Anglo-styled wool suits that would become increasingly fashionable in France over the next decades. All wear wool coats and waistcoats trimmed with narrow bands of metallic galloon (Fig. 4). Those worn by James Grant (at the left) and The Hon. Thomas Robinson (seated) comprise three matching pieces, while Mytton has paired his scarlet coat and waistcoat with black (probably wool) breeches and Wynne is the only one wearing silk—his deep red breeches are velvet. The portrait illustrates the personal choices among the men for the two main coat styles—with a round neck (that would develop a standing collar by the end of the decade) and the frock with a turned-down collar that Englishmen had worn since the early eighteenth century.

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (British). Suit, ca. 1760. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.972a, b. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Cora Ginsburg, 1976. Source: The Met

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (British). Suit, ca. 1760. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.972a, b. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Cora Ginsburg, 1976. Source: The Met

Fig. 3 - Nathaniel Dance (British, 1735-1811). Conversation Piece (Portrait of James Grant of Grant, John Mytton, the Honorable Thomas Robinson, and Thomas Wynne), ca. 1760. Oil on canvas; 96.2 x 123.2 cm. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1946-36-1. Gift of John Howard McFadden, Jr., 1946. Source: PMA

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (British). Coat, ca. 1760. Wool, silk, linen. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.73&A-1962. Given by Lt Col A.D. Hunter from the Gorst Collection. Source: V&A

Men’s coats were always lined with silk during the period and we clearly see the white silk lining in three of the sitters’ coats; Mytton’s coat, however, is lined in black silk, which is more unusual. Known as à la marinière and fashionable from about 1750, Wynne’s sleeve cuffs with vertically applied, scalloped galloon are the same width as the sleeves, while those on Grant and Robinson’s suits retain some of the fullness and the horizontal trimming of the first half of the century (Cunnington 193, 203). All four wear white linen shirts with plain muslin ruffled cuffs (matching jabots are visible on Robinson and Wynne’s shirts); black silk stocks; three-cornered black hats, either trimmed or untrimmed, that were ubiquitous during the century; gleaming white silk stockings with long knitted-in clocks and fashionably low-heeled shoes with oval buckles (Fig. 5). Their status as gentlemen is conveyed by the inclusion of their swords, worn on the left side. Adding to their decidedly English appearance is their unpowdered hair.

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (British). Shirt, ca. 1740-1780. Linen. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.246-1931. Given by Mrs H. Egland. Source: V&A

Fig. 6 - Pompeo Batoni (Italian, 1708–1787). Portrait of a Young Man, ca. 1760–65. Oil on canvas; 246.7 x 175.9 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 03.37.1. Rogers Fund, 1903. Source: The Met

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (Italian). Suit, ca. 1740–60. Silk, metal, cotton, linen. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.2480a–d. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of the International Business Machine Corporation, 1960. Source: The Met

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (Italian). Suit, ca. 1740–60. Silk, metal, cotton, linen. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.2480a–d. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of the International Business Machine Corporation, 1960. Source: The Met

A young man who sat to Pompeo Batoni for his impressive life-size full-length portrait in the early 1760s chose to be represented in formal attire (Fig. 6). As the Met explains, he is surrounded by

“the props Batoni used repeatedly in order to announce various aspects of a Grand Tour education, including a bas relief of Antinous, a statue of Minerva, an armillary sphere, guidebooks to ancient and modern Rome, a volume of biographies of painters, and a volume of Homer’s Odyssey.”

The unidentified sitter shows off his suit that announces its cost through its silk velvet textile (expensive to weave), its brilliant red color (expensive to dye), and the extensive gold embroidery on the coat and white silk satin waistcoat. His white silk stockings and black buckled shoes are similar to those worn by the Englishmen in Dance Holland’s portrait; however, his shirt is trimmed with lace and he wears a powdered wig with its queue enclosed in a black silk bag. His sword and feather-fringed hat on the chair beside him complete his courtly ensemble. Although Batoni primarily painted English subjects, “this sitter’s costume suggests that he may have been French”—and, presumably, accustomed to dressing lavishly (Figs. 7, 8).

In addition to solid colors like those worn by Batoni’s elegant young man, small all-over patterned silks and velvets were especially fashionable in the 1760s for formal suits. In 1762, Thomas Gainsborough painted a portrait of Sir Edward Turner (Fig. 9) “who had recently come into a fortune” and was eager to show off his “nouveau-riche taste” with his matching patterned suit of French silk (Fig. 10 / Ribeiro Art of Dress 45). Dress historian Aileen Ribeiro notes that “the effect… is of an embarras de richesse” and that “although such suits survive in museum collections… it is rare to see them in portraits” (Fig. 11 / Ribeiro Art of Dress 45).

Fig. 9 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727–1788). Sir Edward Turner, 2nd Bt of Ambrosden, Oxford, 1762. Oil on canvas; 229 x 147.5 cm. Wolverhampton: Wolverhampton Art Gallery, OP491. Purchased with the assistance of the Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund, 1971. Source: Art UK

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (French). Suit, ca. 1760–80. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.64.31.2a–c. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1964. Source: The Met

Fig. 11 - Alexander Roslin (Swedish, 1718-1793). Portrait of Baron Thure Leonard Klinckowström, 1758. Oil on canvas; 90 x 71 cm. Helsinki: Sinebrychoff Art Museum, A I 498. Otto Wilhelm Klinckowström. Source: Wikimedia

Returning briefly to Peter Perez Burdett in Derbyshire (Fig. 12), his attire is—understandably—more informal than the dress of his compatriots in Rome. He wears a wool frock coat with a velvet collar and matching breeches and he has turned back the top of his sleeveless double-breasted striped cotton waistcoat to form lapels. At this date, the double-breasted closure was primarily limited to clothing for country pursuits and would not become fashionable daywear until the following decades. His has dispensed with the black silk solitaires of the sitters in Dance’s painting (Fig. 3) and his stockings are thickly ribbed, rather than smooth.

Throughout the century, loose dressing gowns provided men with a comfortable garment to wear in place of the coat when at home. They were a favorite choice for portraiture since they allowed the artist to show off his or her skills at depicting the shimmering surface of plain silks and the complex patterns of brocaded silks and the sitter to display his taste and wealth. In 1769, the Encyclopédiste Denis Diderot penned an essay on his difficulty adjusting to a new scarlet dressing gown. This was probably offered as a gift since he makes it clear that he was reluctant to give up his old, worn, but still serviceable garment, which is certainly not the changeant silk gown he wears in his portrait by Louis Michel van Loo in 1767 (Fig. 13). Outraged, he asks:

“Why on earth did I ever part with it? It was used to me and I was used to it. It draped itself so snugly, yet loosely, around all the curves and angles of my body – it made me look picturesque as well as handsome. This new one, stiff and rigid as it is, makes me look like a mannequin.” (McNeil 22)

Diderot reveals that his old gown served as a pen wiper and duster, as evident from “the long black stripes it bore,” but now, to his dismay, “I look like a rich loafer, and nobody can tell by looking at me what my trade is” and he has become “a slave” to his “new one” (McNeil 22). Additionally irritating is the similar unwanted upgrading of his rooms that used to be filled with “poor bric-a-brac” and now contain an expensive mirror and clock, among other commodities (McNeil 23-24). At the end of this lament, Diderot assures himself that he is “not yet corrupted,” although “who can tell what the passage of time may bring?” (McNeil 25).

Fig. 12 - Joseph Wright of Derby (British, 1734-1797). Detail of Peter Perez Burdett and his First Wife Hannah, 1765. Oil on canvas; 145 x 205 cm. Prague: National Gallery Prague, 4289. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 13 - Louis-Michel van Loo (French, 1701-1771). Portrait of Denis Diderot, 1767. Oil on canvas; 81 x 65 cm. Paris: Louvre Museum, RF 1958. Gift of M. de Vandeul to the French State in 1911. Source: Wikimedia

In another league entirely from Diderot’s scarlet dressing gown is the dazzling and highly impractical banyan worn by Göran Nilsson Gyllenstierna (1724-1799), “a Swedish nobleman, jurist, and from 1781 riksmarskalk (Marshal of the Realm)” (Cora Ginsburg 23) (Figs. 14, 15). The resplendent textile features:

“intermingling plum, leafy green, and silver diaper-patterned vines with an ogival lattice structure…brocaded on a sky-blue silk ground… with cloud-like sprigs. Sprays of purple lilies backed by silver feathers and bouquets of red and pink roses float inside the ogives.” (Cora Ginsburg 23)

Particularly opulent is the use of “remarkably untarnished gold (silver gilt) and silver threads” that “suggests that the silk originated on royal looms” (Cora Ginsburg 23).

Fig. 14 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Banyan, ca. 18th century. Silk, gold and silver thread. Photo by Michael Fredricks. Source: Cora Ginsburg Catalogue 2016

Fig. 15 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Banyan, ca. 18th century. Silk, gold and silver thread. Photo by Michael Fredricks. Source: Cora Ginsburg Catalogue 2016

CHILDREN’S WEAR

(BY SUMMER LEE)

Leading into the eighteenth century, new philosophies emerging from the Age of Enlightenment were changing attitudes about childhood (Nunn 98). For example, in his 1693 publication, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, John Locke challenged long-held beliefs about best practices for child-rearing. A slightly later child development theorist was Jean Jacques Rousseau. Locke and Rousseau both put forward general principles about children’s dress. However, it was not until the 1760s that their ideas were clearly reflected in childrenswear (Paoletti).

Swaddling was a very long-held European tradition where an infant’s limbs are immobilized in tight cloth wrappings (Callahan). However, Locke and Rousseau believed that swaddling infants was bad for their health and physical strength (Paoletti). While the tradition was continued throughout the first half of the century, the practice did begin to decline in the second half.

Babies were then dressed in “slips” or “long clothes” until they began to crawl (Callahan). These were ensembles with very long, full skirts that extended beyond the feet (Nunn 99). Babies also wore tight-fitting caps on their heads.

Once a child was becoming mobile, they transitioned into “short clothes” (Callahan). Unlike long clothes, these ensembles ended at the ankles, allowing for greater freedom of movement (Callahan). Short gowns featured back-opening, stiffened bodices and typically had “leading strings” at the back (Magidson). Leading strings were streamers of fabric used to protect young children from falling or wandering off (“Childhood”). A portrait of three-year-old James Badger from 1760 depicts him in a rather masculine-looking skirted short clothes ensemble (Fig. 1).

When boys were deemed mature enough, they underwent a rite of passage known as “breeching” (Reinier). Breeching referred to the first time a boy wore bifurcated breeches or trousers, symbolizing his entrance into manhood. This typically happened by the time a boy reached the age of seven (Callahan). From that point on, they would be dressed in menswear fashions (see Fig. 2) — although suits for children were now becoming more relaxed (Callahan).

Locke and Rousseau advocated that young children receive more regular hygiene. They also believed that dressing children in many layers of heavy fabrics was bad for their health. For those reasons, linen and cotton fabrics were preferred for babies and very young children because they were lightweight and easily washable (Paoletti).

Fig. 1 - Joseph Badger (American, 1708 - 1765). James Badger, 1760. Oil on canvas; 108 x 84.1 cm (42 1/2 x 33 1/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.85. Rogers Fund, 1929. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French or Italian). Boy's Three Piece Suit: Coat, Waistcoat and Breeches, ca. 1760-1775. Silk and linen. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1904-30a--c. Gift of Mrs. William D. Frishmuth, 1904. Source: Philadelphia Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - Johann Zoffany (German, 1733-1810). John, Fourteenth Lord Willoughby de Broke, and His Family, ca. 1766. Oil on canvas; 101.9 × 127.3 cm (40 1/8 × 50 1/8 in). Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum, 96.PA.312. Source: J. Paul Getty Museum

By the mid-1760s, a new style for young children emerged: a white gown worn with a colored sash around the waist (Fig. 3). This style was worn by very young children of both sexes. The most common sash colors were pink and blue, although they were not used to indicate gender. A colored underslip could also be worn, which would show through the translucent white top fabric (Paoletti). While the style originated with very small children, it quickly became more pervasive as the century continued.

An English family portrait circa 1766 depicts the newly emerging white gown style on three young children (Fig. 3). The couple’s daughter is depicted at the center of the painting, wearing a white frock with a pink sash and tight-fitting cap. Two sons are depicted on either side, wearing white frocks with blue sashes. Blue leading strings are visible on the back of the leftmost boy.

As it was in previous decades, girls typically did not transition into adult dress until their early teens. While the ensemble of a young girl may incorporate elements of fashionable womenswear, she would wear a back-opening bodice (see Fig. 4) and possibly an apron as well.

The group family portraits titled The Children of George Bond of Ditchley (Fig. 5) and The Pybus Family (Fig. 6) were painted in 1768 and 1769 respectively. In both portraits, the youngest children wear the novel white gown and colored sash ensemble. Also in both portraits, older boys dress in menswear suits. There is, however, a discrepancy between the dress of older girls. Two older girls stand on the lefthand side of the 1769 painting. Both girls wear aprons and their silhouettes mirror fashionable womenswear, following the childrenswear traditions of the past. However, in the 1768 painting a tall, older girl wears what appears to be a scaled-up version of what her younger siblings wear. This inconsistency is indicative of the transition occurring in older girls’ dress, which would be complete by the end of the century.

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (English). Gown, ca. 1760. Silk. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.183-1965. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 5 - Hugh Barron (English, 1746-1791). The Children of George Bond of Ditchleys, 1768. Oil paint on canvas; 106 × 139.7 cm (41 3/4 × 55 in). London: Tate, T01882. Bequeathed by Alan Evans 1974. Source: Tate

Fig. 6 - Nathaniel Dance-Holland (English, 1735-1811). The Pybus family, ca. 1769. Oil on canvas; 142.8 x 140.2 cm. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2003.687. Felton Bequest, 2003. Source: Wikimedia Commons

References:

- Buck, Anne. Dress in Eighteenth-Century England. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1148934170.

- Callahan, Colleen R. “Children’s Clothing.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed August 08, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0003223.

- “Childhood.” In European Renaissance and Reformation, 1350-1600, edited by Norman J. Wilson, 319-321. Vol. 1 of World Eras. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2001. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3034600137/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=480f4328.

- Conway, Alison. Private Interests: Women, Portraiture, and the Visual Culture of the English Novel, 1709-1791. 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8182072599.

- Cunnington, C W, and Phillis Cunnington. Handbook of English Costume in the Eighteenth Century. London: Faber & Faber, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/751792955.

- Diderot, Denis. “Regrets on Parting with My Old Dressing Gown; or a Warning to Those Who Have More Taste than Money 1769.” In Fashion: Critical and Primary Sources: The Eighteenth Century, Peter McNeil, ed, Oxford & New York Berg, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/958721947.

- Egerton, Judy. Wright of Derby: Tate Gallery. London: Tate Gallery, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/507499396.

- Fass, Paula S. Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/318387847.

- French, Anne, Aileen Ribeiro, and Viola Pemberton-Pigott. The Earl and Countess Howe by Gainsborough: A Bicentenary Exhibition. S.l.: English Heritage, 1988. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/472516312.

- Ginsburg, Cora. A Catalogue of Exquisite & Rare Works of Art Including 16th to 20th Century Costume, Textiles & Needlework: Winter 2001. New York: Cora Ginsburg, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/51865187.

- Ginsburg, Cora. A Catalogue of Exquisite & Rare Works of Art Including 18th to 19th Century Costume Textiles & Needlework. 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/955855038.

- Lemire, Beverly. “Redressing the History of the Clothing Trade in England: Ready-Made Clothing, Guilds, and Women Workers, 1650–1800.” Dress. 21.1 (1994): 61-74. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/4917451500.

- Levey, Santina M. Lace: A History. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/874134825.

- Magidson, Phyllis. “Fashion.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 344-348. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3402800166/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=0084684d.

- Miller, Lesley E. Selling Silks: A Merchant’s Sample Book 1764. London: V&A Publishing, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083133217.

- “Miss Nelly O’Brien – Joshua Reynolds (1723 – 1792).” Wallace Collection Online, https://wallacelive.wallacecollection.org/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=64928&viewType=detailView.

- Nunn, Joan. Fashion in Costume 1200-2000. Bridgewater, NJ: Distributed by Paw Prints/Baker & Taylor, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/232125801

- Paoletti, Jo Barraclough. “Children and Adolescents in the United States.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: The United States and Canada, edited by Phyllis G. Tortora, 208–219. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed August 28, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch3029.

- Pointon, Marcia. “The Lives of Kitty Fisher.” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies. 27.1 (2004): 77-97. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5156717986.

- Pointon, Marcia. Hanging the Head: Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteenth-Century England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/925097861.

- Pratt, Lucy, and Linda Woolley. Shoes. London: V & A Publications, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/603674113.

- Reinier, Jacqueline S. “Breeching.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 118. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3402800074/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=360a7a45

- Ribeiro, Aileen. Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe 1715-1789. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/873114892.

- Roche, Daniel. The Culture of Clothing: Dress and Fashion in the “ancien Régime”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28632365.

- Rothstein, Natalie. A Lady of Fashion: Barbara Johnson’s Album of Styles and Fabrics. London: Thames and Hudson, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/715272687.

- Rothstein, Natalie. Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century in the Collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Boston u.a: Little, Brown, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/643770082.

- Thom, Danielle. “Kitty Fisher & the Fishing Kitty.” The Droll Hackabout, WordPress, 12 May 2013. https://thedrollhackabout.wordpress.com/2013/05/12/kitty-fisher-the-fishing-kitty/.

- Watkins, Gwen. “The Characters of Kenwood: Mary, Countess Howe.” MFAH, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 22 June 2012. https://www.mfah.org/blogs/inside-mfah/characters-kenwood-mary-countess-howe.

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes: 1600-1900. New York: Theatre Arts Book, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/756979502.

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Women’s Clothes 1600-1930: With Line Diagrams by Margaret Woodward. London: Faber and Faber, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/462461256.

- Wilson, Norman J. The European Renaissance and Reformation, 1350-1600. Detroit, MI: Gale Group, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/45283259.

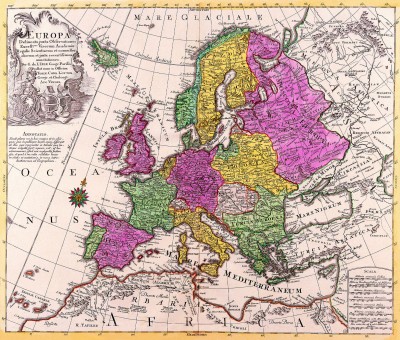

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1760-1769

Rulers:

- England: George III (1760-1820)

- France: Louis XV (1715-1774)

- Spain: Charles III (1759-1788)

Map of Europe in 1760. Source: mapsys.info

Events:

- 1760 – George III becomes King of Great Britain.

- 1763 – Treaty of Paris is signed.

- 1764 – The “Spinning Jenny,” a machine using multiple spindles for spinning yarn, is invented by James Hargreaves.

- 1765 – The caraco emerges as a women’s jacket style in the 1760s.

- 1765 – American Revolution begins.

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 18th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.