OVERVIEW

1880s women’s fashion was defined by the rigidly structured bustle and an abundance of decoration. Dress reformers, influenced by artistic movements, protested these heavy, ultra restrictive trends.

Womenswear

Fashion in the 1880s was increasingly slender and angular, marked by heavy decoration. Throughout the decade, the focus of clothing design was concentrated at the back, a continuation of trends that began in the 1870s (Tortora 390). The extreme restriction placed on women’s bodies through the princess-line corsetry, large bustles, and profuse trim prompted criticism from both artistic and health reformers (Shrimpton 22).

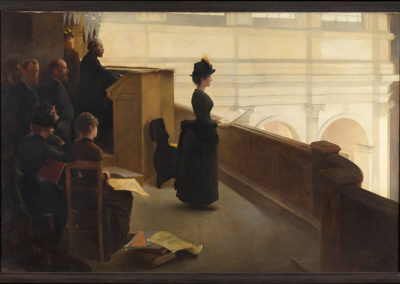

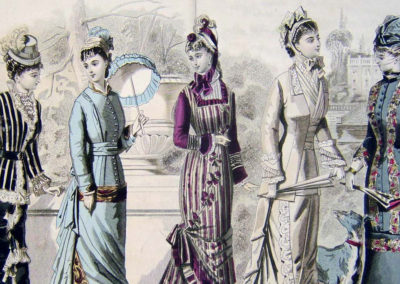

The 1880s featured two distinct silhouettes in women’s fashions. The first was marked by the “princess line” and had begun earlier, around 1876. It was a dress without a horizontal waist seam, instead molded snuggly to the body by vertical seams and tucks, creating a body-hugging silhouette (Fig. 1) (Fukai 214). Similarly, this long, slim line could be created with a cuirass bodice, which emerged as early as 1875; it consisted of a long, tightly-fitted bodice, frequently boned, that extended over the hips (Fig. 2) (Cunnington 276, 320A; Cumming 61). The princess line was marked by the continual diminishment of the soft sloping bustle of the early 1870s, until it nearly disappeared for a short time during the early 1880s (Tortora 390). Instead, minimal fullness emerged from below the hips, with decoration concentrated low on the back (Fukai 214; Tortora 390).

Fig. 1 - Edgard Farasyn (Belgian, 1858-1938). Sad News, ca. 1880-1883. Oil on canvas; (47.2 x 28.8 in). Newcastle Upon Tyne: Laing Art Gallery, TWCMS : G1749. Gift from Mr Jameson, 1948. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 2 - C.L. Kempf (American). Three quarter length portrait of elderly lady in a plaid dress, ca. 1880. Photographic print on cabinet card; 17 x 11 cm. New Haven, CN: Yale University: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, 2002262. Source: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Day Dresses, May 1886. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Special Collections, RS 21/07/009. Source: Iowa State University Special Collections

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown. Bustle, ca. 1885. Cotton twill, cotton braid-covered steel, cotton braid cord. Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2007.211.399. Purchased with funds provided by Suzanne A. Saperstein and Michael and Ellen Michelson. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

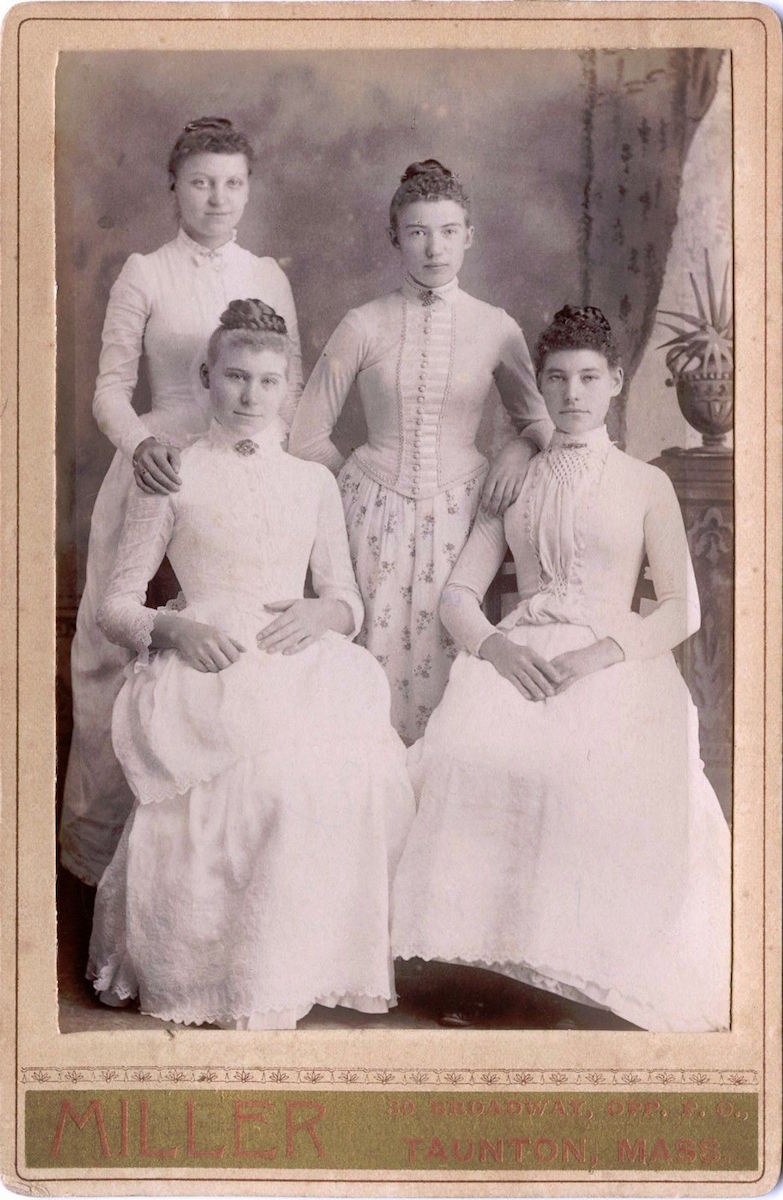

Fig. 5 - Photographer unknown. Four Young Women, ca. 1885. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 6 - Alvan S. Harper (American, 1847-1911). Woman with a fan made of feathers, ca. 1886. Glass photonegative; (7 x 5 in). Tallahassee: State Library and Archives of Florida, HA00288. Source: Florida Memory

The second silhouette of the 1880s began developing around 1883 and disappeared in the 1890s. By 1884, the bustle had returned, this time a hard, shelf-like protrusion that projected from the small of the back (Fig. 3). This bustle was rigidly structured, as opposed to the soft, draped bustle of the 1870s (Tortora 386, 390). The undergarments contrived to support this look became increasingly complex. The “Lillie Langtry” bustle was a series of metal bands that could be folded up to allow the wearer to sit (Laver 198). Figure 4 depicts the common “lobster tail” bustle. The bustle reached its largest size by 1886, “whereon a good-sized tea tray might be carried,” as one writer commented at the time (Shrimpton 24-25). After about 1888, the bustle began to slowly shrink in size until 1891, when it gave way to the bell-shaped skirts of the 1890s (Fukai 239).

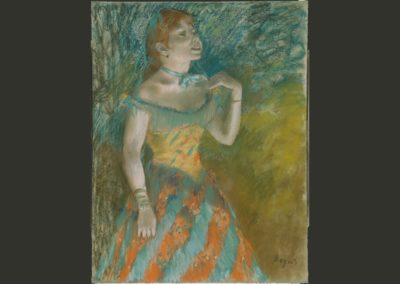

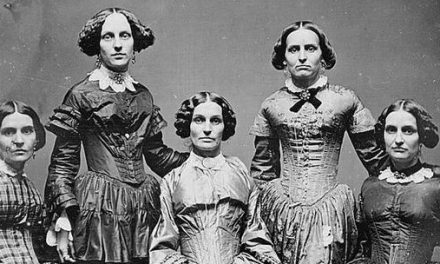

Throughout the 1880s, day bodices and dresses featured high, narrow shoulders descending into impossibly tight sleeves, a departure from the low, sloping shoulders of the past few decades. Collars were tall and fitted, sometimes boned for shaping (Fig. 5). During the day, hemlines were usually just above the floor (Tortora 391). Bodices could feature long basques, and many bodices were designed with central panels that often imitated a jacket and vest, drawing inspiration from menswear fashions (Fig. 6). Skirts usually featured overskirts that were swagged and tucked up in various ways to reveal the underskirt, which was frequently ruffled or pleated; these overskirts ranged from from pannier-type styles (Fig. 6) to the longer, gently draped polonaise style (Fig. 7) (Cunnington 320B-321; Tortora 391). This style was sometimes referred to as the “Dolly Varden” look, named after the character of the same name in Dickens’ popular novel Barnaby Rudge, set in the eighteenth century, underscoring the look’s revivalism influences (Fukai 218; Laver 193). Late afternoon and evening dresses (Fig. 8) featured shorter sleeves, ranging from elbow length to mere shoulder straps, lower necklines, and frequently long, sumptuous trains (Fukai 225-235).

The types and extravagance of outerwear expanded in the 1880s, a development that began in the 1870s. The bustle silhouette was better accommodated by jackets and coat-like garments, as opposed to cloaks and capes that were dominant earlier in the century. Jackets were increasingly worn and cut to fit over the bustle style of any particular year (Tortora 392). Outerwear of the 1880s was particularly marked by the mantle or dolman, a garment featuring a wide sleeve cut with the body in one piece, and short basques in the back that exposed the bustle (Fig. 9). Often, a dolman had long mantlet ends hanging in the front (Cumming 67). Emilie Pingat, one of the most significant couturiers of the era, was known for his luxurious dolmans (Coleman 183).

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown. Day dress, 1886. Silk. Bath, U.K.: Fashion Museum Bath. Source: Fashion Museum Bath Twitter

Fig. 8 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1906). Les Demoiselles de Province, 1885. Oil on canvas; (57.9 x 40.2 in). London, U.K.: Christie's. Source: Christie's

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown. Dolman, 1885-1889. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.41.74.1. Gift of Mrs. Arthur Francis, 1941. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Perhaps womenswear in the 1880s was most marked by the weightiness of decoration (Fig. 10). Womenswear featured an extensive use of trims, including ribbons, ruffles, flounces, shirring, bows, and lace; this over-decoration was not only seen in the evening, but throughout the day (Fukai 216). Dress historian Jayne Shrimpton wrote,

“The resemblance between dress drapery and furnishing fabrics was often noted at around this time, particularly the vogue for rich, dark colors and sumptuous three-dimensional effects using velvet, plush (cotton velvet), satin brocade and embossed fabrics” (25).

Women began to wear their hair more neatly in the 1880s. The long, cascading curls of the previous decade were now tucked up into tight chignons, particularly as the high collars of the mid-1880s came into vogue (Tortora 393). Hats were worn directly on top of the head, and they grew greatly in height becoming tall and narrow, eventually rising to such heights they were mocked as “Four Stories and a Basement” (Ginsburg 92). This new millinery provided a great deal of space for decoration, and thus hats of the 1880s were elaborately trimmed with ribbons, flowers, lace, and most importantly a gruesome amount of feathers and entire stuffed birds (Fig. 11). It was during the 1880s that bird populations began to be slaughtered in such numbers, that many species became endangered (Shrimpton 26). It is not a coincidence that the American Audubon Society was founded in 1886, and the English Royal Society for the Preservation of Birds formed in 1889 (Ginsburg 92).

Fig. 10 - Emile Pingat (French, 1820-1901). Day dress, 1883. Cut velvet silk and chenille fringe. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC10343 2000-26-2AC. Source: Kyoto Costume Institute

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown. Evening hat, ca. 1880. Silk, whole birds, feathers, jet. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.2103. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

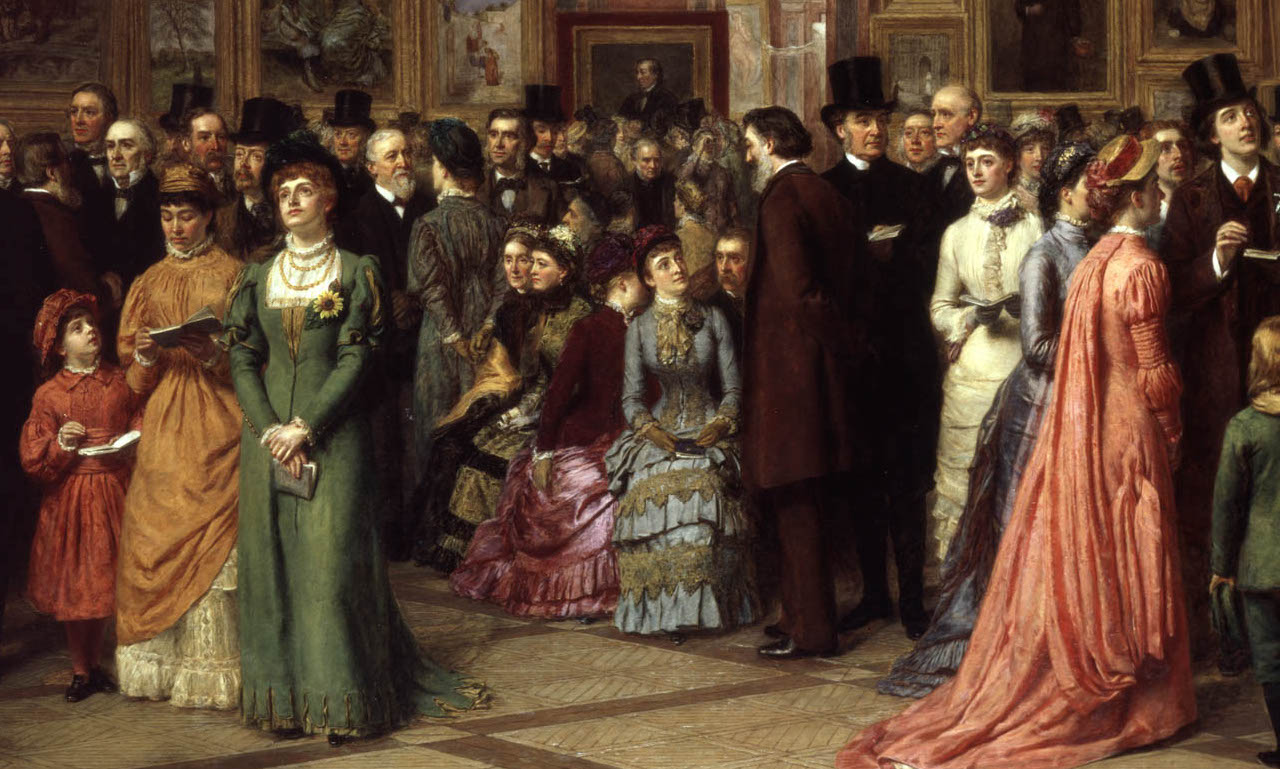

Fig. 12 - William Powell Frith (British, 1819-1909). A Private View at the Royal Academy, 1881, detail, 1883. Oil on canvas. Pope Family Trust Private Collection. Source: Wikipedia

No discussion of 1880s fashion is complete without mention of the Aesthetic Movement and the calls for dress reform. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, several artistic groups were reacting against the new, industrial era, and looking to the past for true beauty. These movements, arguably, all coalesced in their influence on fashion in the 1880s. The Aesthetic Movement, with origins in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of artists which were inspired by medieval and Renaissance themes, came into its own in the 1880s (Ellis 35-36). Aesthetes argued for “art’s for art’s sake,” and adopted reform clothing based on the art of the Pre-Raphaelites (Lambourne 6). For women, Aesthetic dress consisted of a dress with a loosely-fit waist, puffed sleeves, and, most importantly, was often worn without a corset or heavy petticoats and bustles (Tortora 384). Aesthetic dress was also notable for its earth-toned colors, such as mossy green and ochre yellow (Shrimpton 22). Figure 12 depicts Aesthetic women on either side of the painting, which contrasts with women wearing mainstream fashions in the center. The dress of Aesthetes influenced the Rational Dress Society, founded in 1881, which argued against the constrictive and cumbersome mainstream fashion for women (Laver 200). However, the followers of the Rational Dress movement were more concerned with the unhealthiness of current fashions, than artistic pursuits. They protested corsetry in particular, and argued that women’s dress prevented them from being full, productive members of society (Mitchell 77-83).

Neither reform, Aesthetic dress nor Rational Dress, were accepted into the mainstream, and were both mercilessly mocked in the press (Laver 200). Nevertheless, some influence can be seen. For example, the famous London store, Liberty, opened its dress department in 1884 and carried looser styles inspired by the Aesthetes and dress reformers (V&A). The tea gown shown in Figure 13, reflects influence from both reforms, especially in its “medieval” bands of embroidery. Tea gowns were soft dresses, often worn with a loosened corset or without a corset at all, meant to be worn at home, perhaps while visiting with female friends. First introduced in the 1870s, tea gowns became increasingly popular through the 1880s (Tortora 387). A more relaxed garment, the influence of Aesthetic and Rational Dress ideas on tea gowns is clear.

Fig. 13 - Designer unknown. Tea Gown, ca. 1882. Silk and wool. Kent, OH: Kent State University Museum, 1995.017.0017. Transferred from the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio. Source: Kent State University Museum

Fashion icon: oscar wilde (1854-1900)

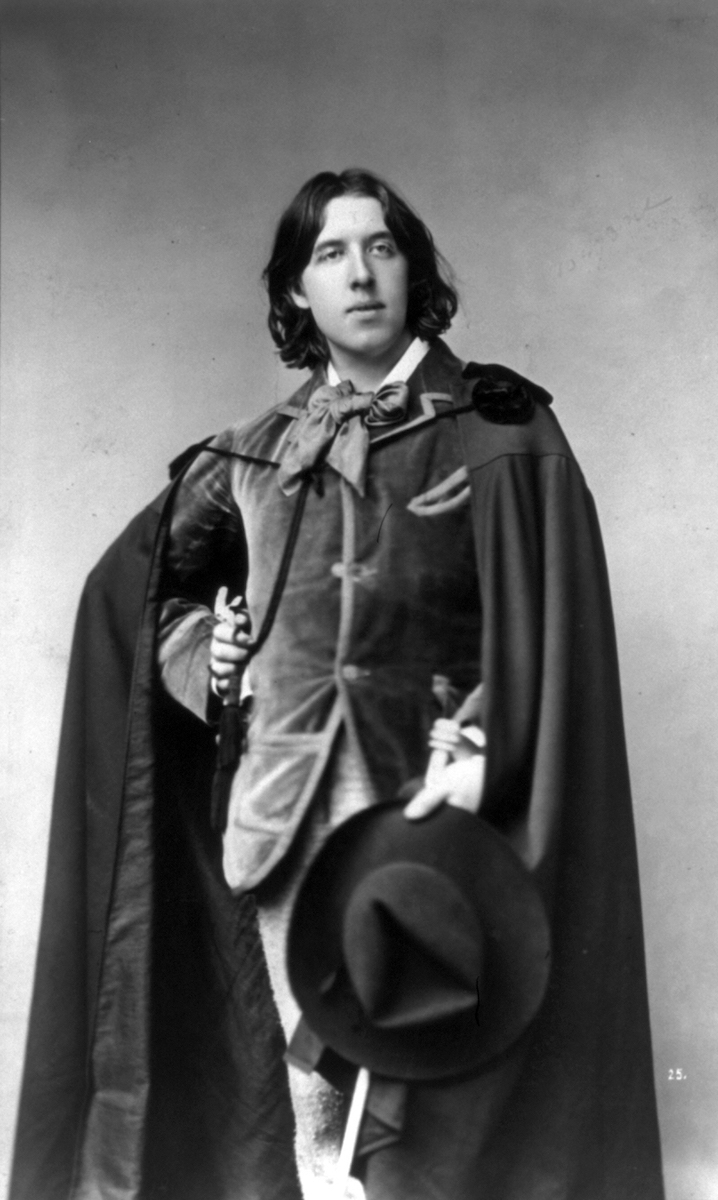

Fig. 1 - Napoleon Sarony (American, 1821-1896). Oscar Wilde, 1882. Albumen print. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-69512. Source: Wikipedia

In 1885, the famous Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde wrote in his essay, “The Philosophy of Dress”:

“Fashion rests upon folly. Art rests upon law. Fashion is ephemeral. Art is eternal.” (Mitchell 87)

Perhaps, then, it would be more accurate to refer to Wilde as an anti-fashion icon. However, the significance of Oscar Wilde as a voice on 1880s fashion and dress cannot be overstated. As one of the leading adherents of the Aesthetic Movement, Wilde made its tenets famous across the Western world. In 1882, he embarked on a lecture tour of the United States, promoting Aestheticism and becoming a nationwide sensation (Lambourne 137). He was so inextricably tied to the movement, that when Gilbert and Sullivan sought to parody Aestheticism in their 1881 operetta, Patience, the leading character was based on Wilde (Tortora 384).

Wilde was keenly aware of the importance of dress in conveying an idea, and he developed his own version of Aesthetic dress (Fig. 1): a velvet suit of knee-breeches and soft jacket, flowing tie, and sometimes a Cavalier inspired cloak and hat (Tortora 384). The look was completed with his long, smoothly curled hairstyle (Lambourne 134-135). He advocated that artistic dress should be taken up by all, and was particularly distressed by the restrictive excesses of women’s fashions. In “Philosophy of Dress,” he argued against the very concept of fashion, writing:

“A fashion is merely a form of ugliness so absolutely unbearable that we have to alter it every six months!” (Mitchell 87)

As with the larger Aesthetic and Rational Dress movements, Wilde’s ideas were not widely accepted. In fact, he was a constant target of ridicule throughout the decade. His strange costumes were cartoonishly replicated across the press (Lambourne 141-142). Nonetheless, his ideas about fashion and dress had an outsized presence in any discussion of dress during the 1880s.

Menswear

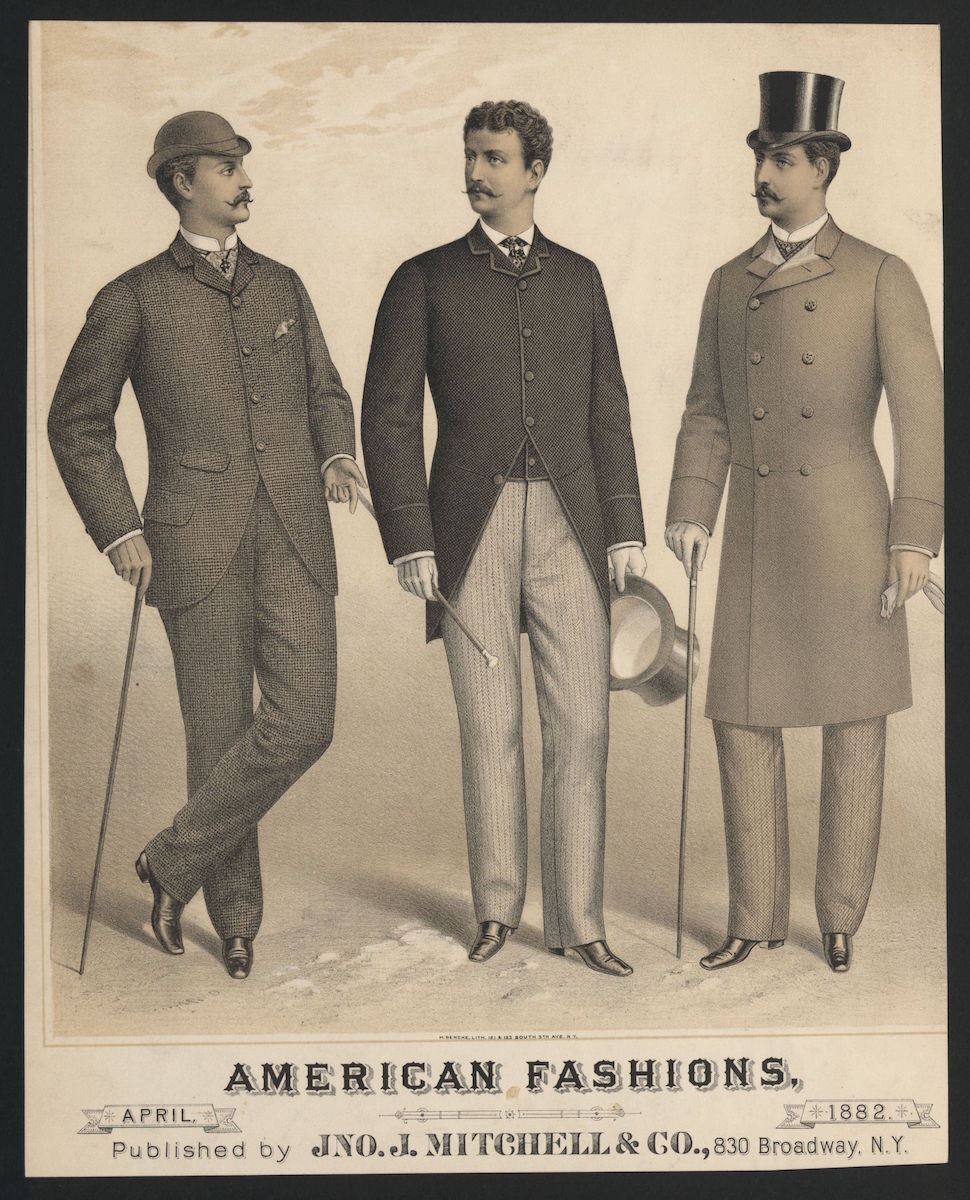

Men’s clothing in the 1880s was marked by a long, slender frame. Suits were cut closer to the body, creating a tall, slim line (Shrimpton 38). The frock coat, featuring a waist seam with a full skirt, remained the most formal daywear in town (Fig. 1) (Cumming 87; Laver 202). The morning coat, a cutaway jacket with a waist seam, was a slightly less formal choice for daywear (Fig. 2). A morning coat was more versatile than the frock coat; it could be quite formal in black and paired with striped trousers, or less formal in a tweed and cut shorter in length (Shrimpton 39). The sack or lounge suit, marked by its relaxed jacket, single or double-breasted, without a waist seam, remained the most informal choice for day (Tortora 401). Figure 3 depicts all three styles.

Fig. 1 - Alvan S. Harper (American, 1847-1911). Man holding a top hat, ca. 1880s. Glass photonegative; (7 x 5 in). Tallahassee: State Library and Archives of Florida, HA00426. Source: Florida Memory

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (English). Man's Morning Coat and Vest, ca. 1880. Wool twill with wool braid trim. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2010.33.15a-b. Purchased with funds provided by Michael and Ellen Michelson. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. American Fashions: Day Menswear, April 1882. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Pinterest

For evening occasions, a formal tailcoat, with a matching double-breasted evening waistcoat and a white bow tie, was required (Fig. 4). In the 1880s, the notched collar of previous years’ tailcoats were often replaced with a continuous rolled collar faced in satin. A new evening option was introduced in the 1880s; a dress version of the lounge jacket became a less formal evening ensemble worn with black tie. This ensemble became known as a tuxedo in the United States and a dinner jacket in the United Kingdom (Tortora 401-402; Waugh 115).

Fig. 4 - James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Arrangement in Flesh Colour and Black: Portrait of Theodore Duret, 1883. Oil on canvas; 193.4 x 90.8 cm (76 1/8 x 35 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 13.20. Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1913. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Photographer unknown. Tennis Players, ca. 1885. Hartford CT: Connecticut Historical Society. Source: Connecticut Historical Society Museum and Library

Sportswear played a special role in menswear during the 1880s. The blazer, in particular, became quite fashionable for wear at the seaside or for sports such as rowing, tennis, and cricket. The blazer, a single-breasted lounge jacket, often made in brightly colored stripes (Fig. 5), was usually paired with light colored flannel trousers for such occasions (Shrimpton 40). Casual doubled-breasted jackets, known as reefers, were also a suitable choice for summer sports and picnics. For shooting and country activities, a Norfolk jacket, marked by its pleated back and belted waist, was the most common ensemble. It was usually paired with loose knee-breeches and gaiters (Tortora 401; Laver 202, 204).

Most jackets buttoned quite high in the 1880s, and thus waistcoats took on less importance. They were frequently made in the same fabric as the jacket and trousers. The tall silhouette of menswear was accentuated by high, stiffened collars that came into vogue. These collars were often removable, along with the cuffs, and could be a stand or fold-over collar. Both bow ties and knotted neckties were fashionable; neckties were often accessorized with a tie pin or stick pin (Tortora 401; Shrimpton 37-38). The two dominant hats for men were the formal black silk top hat or the less formal bowler hat. Exaggeratedly tall bowler hats were particularly fashionable, further underscoring the tall, slim look of the decade (Fig. 6) (Shrimpton 38).

Fig. 6 - Numa & Fils Blanc. Arthur, Duke of Connaught, August 1887. Albumen print; 7.0 x 4.1 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2904540. Source: Royal Collection Trust

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Ballater W. Watson. Group, Balmoral, Portraits of the Royal Children, September 1885. Albumen print; 9.7 x 13.6 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2904323. Source: Royal Collection Trust

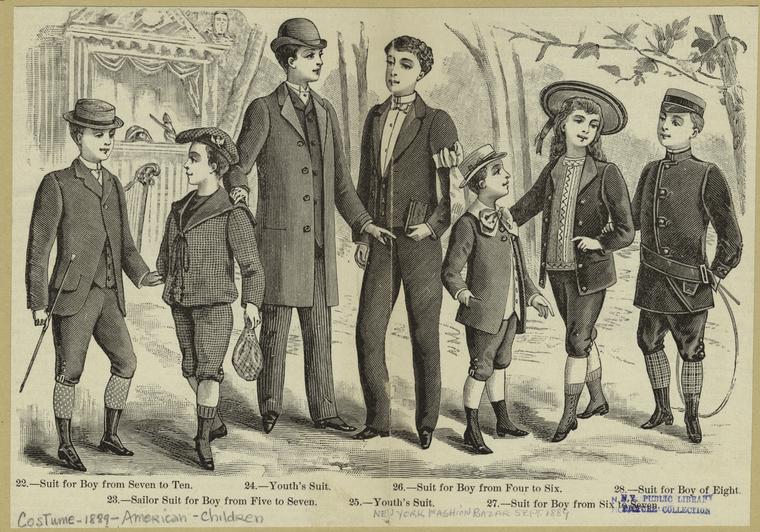

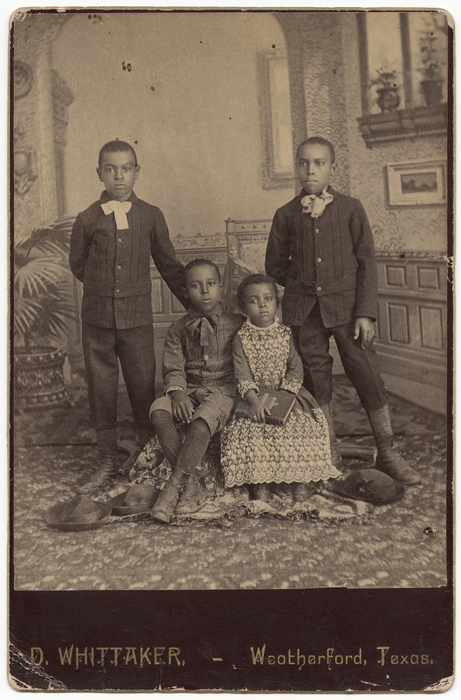

Throughout the nineteenth century, babies and toddlers of both sexes wore long white dresses (Fig. 1), usually with long sleeves (Paoletti 85; Shrimpton 43). In toddlerhood, color could be introduced and dresses shortened to allow movement (Tortora 405). These dresses were loose and often featured rows of tucks or smocking (Shrimpton 45). Young boys were given their first pair of pants (known as breeching) around the age of five. After this, boys wore suits consisting of short trousers or knickerbockers that buckled at the knee, and a jacket (Fig. 2). The pleated and belted Norfolk jacket was especially fashionable (Fig. 3), alongside blazers and reefers (Tortora 404; Rose 139).

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. Suits for Boys and Teenagers, 1889. Print; (5.75 x 8 in). New York: The New York Public Library, b17122166. Source: The New York Public Library

Fig. 3 - Daniel Whittaker (American, 1832-1910). Jeff, George, Oliver, and Lillie Wayes, 1880s. Albumen silver cabinet card; (5 1/2 x 4 in). New York: International Center of Photography, 390.1990. Gift of Daniel Cowin, 1990. Source: International Center of Photography

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown. Ensemble, 1885. Silk, cotton, leather, metal, wood. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.3293a–f. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Carl Backofen (German, 1853-1909). Princess Irene and Princess Alix of Hesse, March 1880. Albumen print; 14.1 x 9.8 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2903497. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 6 - Kate Greenaway (British, 1846-1901). Young Girls, 1880s. Source: Bumble Button Blog

Like the general trend in menswear, boys’ clothing grew quite narrow in the 1880s (Shrimpton 47). The sailor suit, first introduced in the 1840s, became a favorite for boys from about the age of four through early adolescence (Olian vi; Shrimpton 49). The 1880s saw a fad for “Highland dress,” an imitation of the Scottish kilt, among the higher classes (Shrimpton 48). The Aesthetic Movement also exercised influence in boys fashions. The “Little Lord Fauntleroy” suit began to gain favor in 1886; it consisted of a velvet tunic and knickerbockers, flounced shirt, and a wide lace collar (Fig. 4). Named for the eponymous hero of a children’s book, the author claimed his character’s costume was influenced by the Aesthetic dress of Oscar Wilde (Tortora 405).

The introduction of the princess line narrowed girls’ dresses, as it did their mothers’. The 1880s saw girls’ dresses most frequently cut from the shoulder to hem, without a waistline seam, and often featuring a wide sash worn low between the hips and the knee. It was common for the skirt to be pleated (Fig. 5) (Tortora 404). The sash often tied in a pronounced bow in the back, echoing the bustles of adult fashions (Shrimpton 54). Indeed, girls were miniature versions of their mothers, and their dresses could be just as elaborate. While earlier in the decade, the princess line was often cut forgivingly for young girls and may have allowed a child to move, by the middle of the decade, all the restriction endured by adult women was forced onto young girls, as sleeves tightened and the rear projected evermore. The heavy trim seen on their mother’s dresses, frequently weighed down young girls as well. Young girls even wore the tall bonnets and hats then in vogue (Rose 85; Shrimpton 54).

However, some became concerned that these cumbersome fashions were not healthy for young girls. In November 1888, a writer at La Mode Illustreé wrote that a simple tunic-dress, gathered at the neck and tied loosely at the waist, was best for girls aged seven to twelve (Olian iv). The Aesthetic Movement underscored this concern, chiefly through the introduction of “Kate Greenaway” dresses. Greenaway was an Aesthetic Movement illustrator who created many children’s book illustrations featuring young girls in loose, Empire-waist dresses and protective straw bonnets (Fig. 6) (Tortora 404). These dresses, praised by many for their supposed health benefits, saw some favor in the 1880s, a trend that would continue into the 1890s (Mitchell 173).

References:

- Coleman, Elizabeth Ann. The Opulent Era: Fashions of Worth, Doucet, and Pingat. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd., The Brooklyn Museum, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/469409564

- Cumming, Valerie ed., The Dictionary of Fashion History. New York: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1003643284

- Cunnington, C. Willett. English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Guide with 1,117 Illustrations. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868281120

- Ellis, Martin, Victoria Osborne, and Tim Barringer. Victorian Radicals: From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts & Crafts Movement. New York: American Federation of Arts, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1099429593

- Fukai, Akiko, ed. The Collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute: Fashion, A History from the 18th Century to the 20th Century. Kyoto: Taschen, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/81452017

- Ginsburg, Madeliene. The Hat: Trends and Traditions. London: Studio Editions, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/22914760

- “How Arts and Crafts Influenced Fashion.” Victoria & Albert Museum. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/how-arts-and-crafts-influenced-fashion

- Lambourne, Lionel. The Aesthetic Movement. London: Phaidon Press Ltd., 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1120913632

- Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/966352776

- Mitchell, Rebecca N., ed. Fashioning the Victorians: A Critical Sourcebook. London: Bloomsbury, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1085349620

- Olian, JoAnne, ed. Children’s Fashions 1860-1912. New York: Dover Publications, 1994. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28963700

- Paoletti, Jo B. Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/809762103

- Rose, Clare. Children’s Clothes: 1750-1985. London: BT Batsford, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/317672212

- Shrimpton, Jayne. Victorian Fashion. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/896980798

- Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865480300

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes: 1600-1900. New York and London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927414537

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1880-1889

Rulers:

- America:

- President James Garfield (1881)

- President Chester A. Arthur (1881-85)

- President Grover Cleveland (1885-89)

- President Benjamin Harrison (1889-93)

- England: Queen Victoria (1837-1901)

- France:

- President Jules Grévy (1879-87)

- President Marie François Sadi Carnot (1887-94)

- Spain:

- King Alfonso XII (1874-85)

- Regent Maria Christina of Austria (1886-1902)

- King Alfonso XIII (1885-1931)

Europe 1884. Source: Omniatlas

Events:

- 1881 – Population of Paris reaches 2,200,000

- 1882 – Oscar Wilde embarks on a tour of America. His “too too and utterly utter” aesthetic fashion style is regularly remarked upon in the media.

- 1883 – Brooklyn Bridge, the first wire suspension bridge, is built

- 1885 – First motorcar built; first Chicago skyscraper; Thomas Edison invents the first movie in New Jersey

- 1886 – Last Impressionist group exhibition

- 1887- Fancy Dresses Described by Ardern Holt is published.

- 1888 – George Eastman’s first amateur cameras

- 1888 – Portable Kodak camera perfected

- 1889 – Eiffel Tower built

- 1889 – Safety bicycle introduced

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Womenswear Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Menswear Periodicals / Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 19th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.