OVERVIEW

Following the significant changes of the previous decade, the 1450s was a period of relative stability in fashion. The new proportions and trends of the 1440s developed further and were refined. Men’s outer garments grew shorter, and women’s headdresses grew higher, until they became the tall pointed cones with hanging veils that have captured the imagination ever since.

Womenswear

The foundation of women’s dress in the 1450s continued to be the chemise, the undergarment of undyed linen that was worn by all women, whether they were rich or poor (Boucher 445). The Labors of the Months (Fig. 1), a tapestry made in Alsace, in the borderlands between French, Burgundian and German territories, shows men and women doing farm work during the latter half of the year. One woman (Fig. 2) has tucked up the skirts of her dress to reveal a grayish, rough-textured chemise that hovers above her ankles. The chemise was a washable underlayer that protected the next layer of clothing, the dress. The dresses in the tapestry are loose-fitting and not very different from the medieval tunics they were descended from. They could be made of linen or wool and worn in layers according to the season. Dyed wools were no longer completely unaffordable to the working classes (Piponnier and Mane 88), though if a rural woman had a deep blue dress as seen in figure 2, it is likely she would reserve it for church-going on Sunday. The dresses have straight sleeves that can be rolled up or down and skirts wide enough to tuck up for greater freedom of movement; in any case they do not trail on the ground. Practicality also dictated accessories like wooden shoes and woven straw hats.

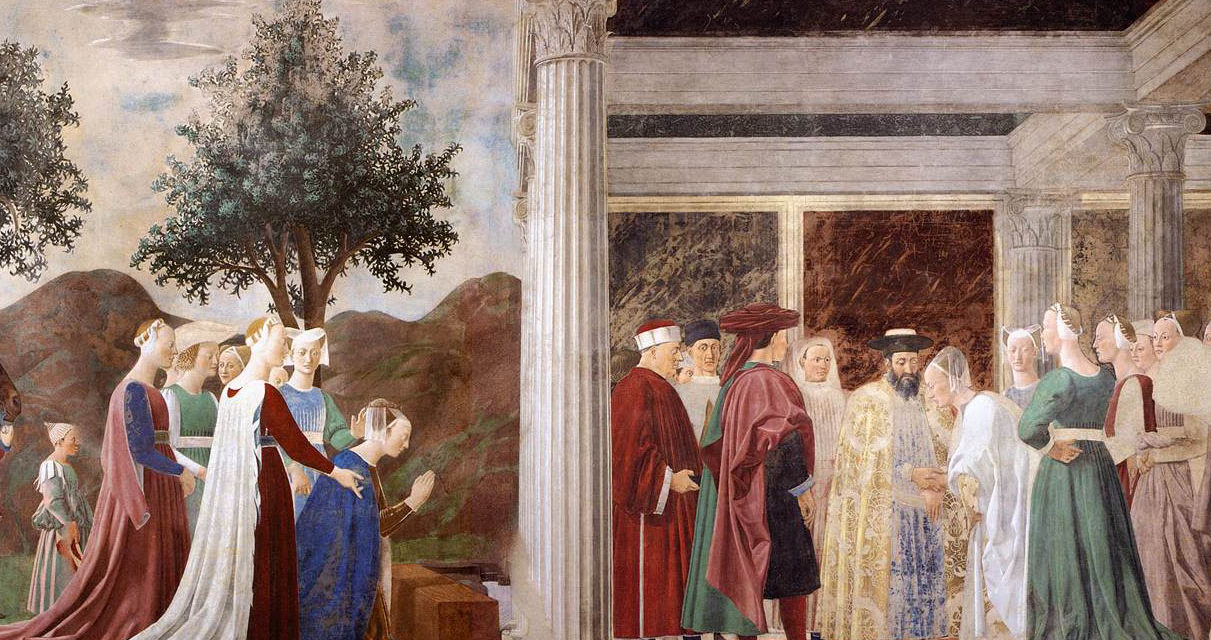

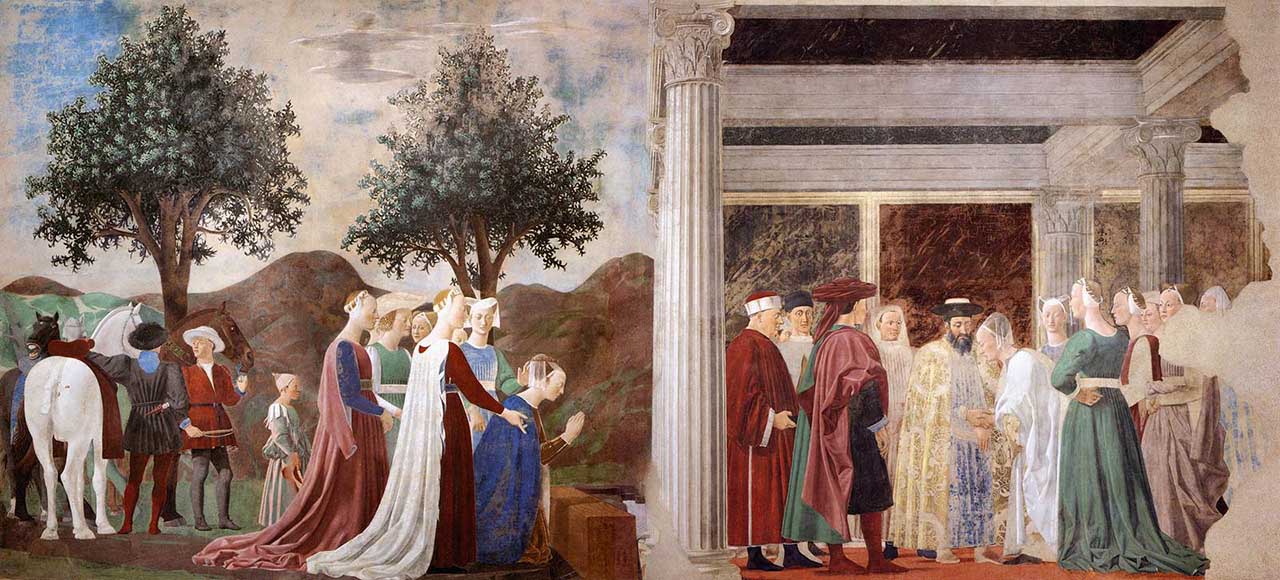

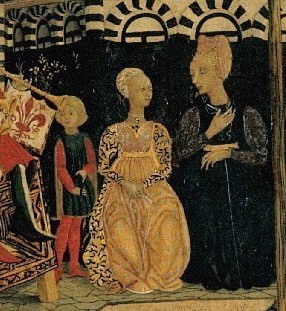

By contrast, the dresses seen in Piero della Francesca’s frescoes The Legend of the True Cross (Fig. 3), in the Church of San Francesco in Arezzo, display the characteristics of the most advanced fashions of the decade in Italy. The fresco cycle, begun in 1452, tells a legendary medieval story of the cross upon which Christ was crucified. To bring such stories to life, artists commonly represented biblical or mythological figures dressed in contemporary fifteenth-century clothing.

Fig. 1 - Maker unknown (French). Labours of the Months, partial view, 1440-60. Tapestry; woolen wefts, linen warp; 39 x 272.2 cm. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 6-1867. Source: VAM

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French). Detail from the Labours of the Months, 1440-60. Tapestry; woolen wefts, linen warp; 39 x 272.2 cm. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 6-1867. Source: VAM

Fig. 3 - Piero della Francesca (Italian, c.1415-1492). The Legend of the True Cross: Procession of the Queen of Sheba; Meeting of the Queen of Sheba with King Solomon, 1452-66. Fresco; 336 x 747 cm. Arezzo: Cappella Maggiore, San Francesco. Source: Web Gallery of Art

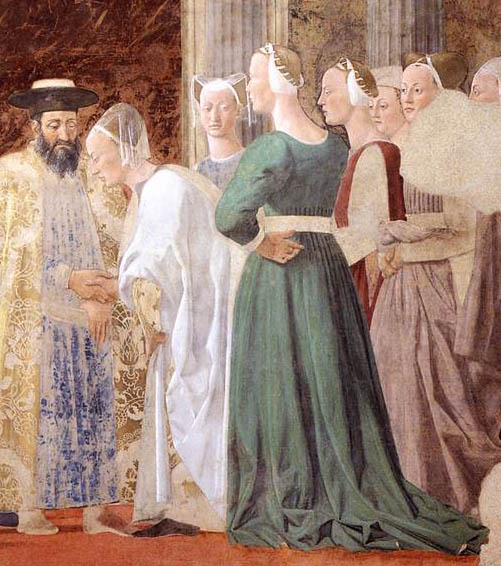

Fig. 4 - Piero della Francesca (Italian, c.1415-1492). Detail from the Procession of the Queen of Sheba; Meeting of the Queen of Sheba with King Solomon, 1452-66. Fresco; 336 x 747 cm. Arezzo: Cappella Maggiore, San Francesco. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 5 - Piero della Francesca (Italian, c.1415-1492). Detail from the Procession of the Queen of Sheba; Meeting of the Queen of Sheba with King Solomon, 1452-66. Fresco; 336 x 747 cm. Arezzo: Cappella Maggiore, San Francesco. Source: Web Gallery of Art

The young woman in green who witnesses The Meeting Between the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon (Fig. 4) might have stepped from the streets of Arezzo. In this region of Italy, her dress would be called a gamurra (Herald 47). It was made of silk or a fine wool, and lined in linen to protect the fabric and give the garment body. We can see that it is constructed with a seam at a high waistline, where the bodice of the dress is joined to the skirt. The skirt is pleated with narrow “pipe pleats” and the fullness released to trail on the ground. At the low scoop neckline of the dress, and at the bottom of the sleeves, we get a glimpse of the fine white linen chemise worn underneath.

In the other scene in this fresco (Fig. 5) the Queen of Sheba is kneeling, surrounded by her attendants. Some of them are wearing an outer garment over their gamurre. The young woman furthest to the left wears a pink cioppa, the Italian equivalent to the northern European houppelande (Herald 50), over a blue gamurra. The sleeves of the gamurra are cut in two sections, with the upper section very full, joined above the elbow to the fitted lower section, a style called “Lombard sleeves.” (Van Buren and Wieck 168). The sleeves of the cioppa are in the Tuscan style, called maniche a gozzi, slit down the front so that the arm can be freed entirely, leaving the sleeve to hang from the shoulder (Frick 192). The woman to her right wears a narrow white cape made of a single width of cloth, its edges decorated with a decorative cutting technique called frappature in Italy and dagging in northern Europe (Herald 56). Like the cioppa, it trails on the ground.

In both scenes in this fresco, the Queen of Sheba is the most heavily dressed figure, envelopped in a mantle (mantello), whether white (Fig. 4) or blue (Fig. 5) (Herald 50). The women have elongated necks, heightened by the scooped back necklines of their dresses and outer garments. Their chests are very gently rounded, almost flat, and although they wear belts, their waistlines are wide, so as not to interrupt the free-flowing drapery. Although their garments are unmistakably modern, they recall the draped costume of antiquity, as intended. The hairstyle shared by several of the young women, in which the hair is wrapped with strips of linen and coiled around the head, is another allusion to antiquity. One woman, behind the Queen of Sheba in figure 5, wears her hair in the “pair of temples” style of earlier decades (Van Buren and Wieck 317-318) but the horn-shaped cones of hair are not very large. The Queen of Sheba has her hair covered with linen and then encased in a cylindrical cap that recalls the Italian balzo of the 1430s (Herald 50); in northern Europe it might be called a turret (Van Buren and Wieck 319), but it is a very restrained version of that headdress (see Fig. 9). It is surmounted by a fine linen veil, anchored in place by her crown.

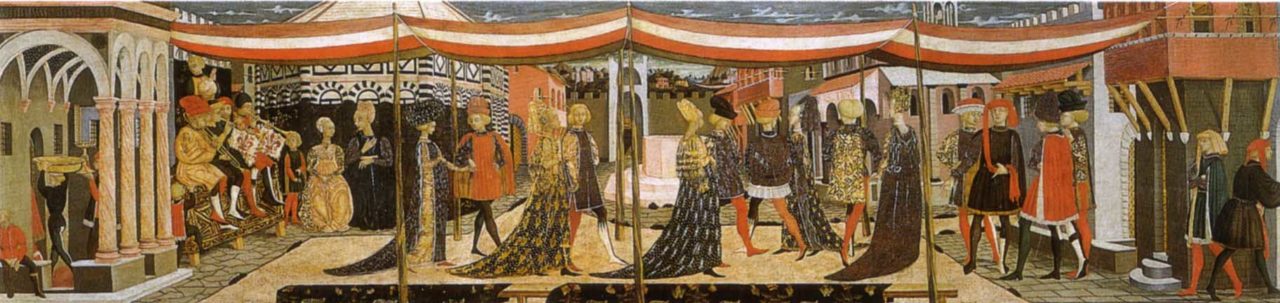

Fig. 6 - Giovanni di ser Giovanni Guidi (Italian, 1406-1486). The Adimari Cassone, 1450s. Tempera on panel; 88.5 x 303 cm. Florence: Galleria dell'Accademia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Legend of the True Cross frescoes represent Italian fashion of the 1450s at its most avant-garde, with multiple references to ancient costume. The panel painting known as the Adimari Cassone (Fig. 6) represents it at its most luxurious. A cassone was a wooden marriage chest, usually with carved and painted decoration, used by a bride to store what she would need in her new household, including gifts that she had received. A wealthy bride might have dozens of fine linen chemises, silk gamurre and outer garments, embroidered sheets, velvet hangings, etc. (Frick 128-131). During the wedding procession the cassone would be carried through the streets to her new home (Witthoft 50-51). In the central scene of the Adimare Cassone five lavishly dressed couples dance in a circle under a striped canopy, with the Baptistry of Florence in the background (Fig. 7). The women are dressed in the most expensive Florentine silk textiles, brocaded or embroidered with gold. Three of them wear cioppe with a gozzi sleeves; the others wear giorneas, sideless capes made of two widths of fabric joined at the shoulders (Herald 218). All the outer garments trail on the ground for several feet.

The woman on the far left, whose blue voided velvet giornea is worn over a golden gamurra, has a headdress based upon a padded roll covered with fabric. In northern Europe it was called a bourrelet (Van Buren and Wieck 296), in Italy the ghirlanda (Herald 217), and in both regions it was a well-established style. What makes this ghirlanda special is that it appears to be covered in peacock feathers. The other women wear headdresses based upon the horn-shaped “pair of temples” hairstyle, but the cones of hair, covered in glittering gold-embroidered hairnets, are taller than in earlier decades, and nearly vertical, as if they are about to merge into the single turret worn in northern Europe. The second woman from the left has topped her hairstyle with wired linen veils. The second from the right has draped voided velvet panels on hers. In Florence, such lavish displays at public wedding festivities were seen as necessary to maintain family prestige, but after the festivities were over, the luxurious clothing could be sold to pawnbrokers or dealers, and transformed into family capital (Frick 131).

Fig. 7 - Giovanni di ser Giovanni Guidi (Italian, 1406-1486). Detail of the Adimari Cassone, 1450s. Tempera on panel; 88.5 x 303 cm. Florence: Galleria dell'Accademia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, at northern European courts fashion Italian silks continued to play an important part in the visual magnificence necessary to maintain power. In Portrait of a Female Donor (Fig. 8), no doubt the right-hand panel to a lost altarpiece, Petrus Christus has portrayed a fashionably dressed young woman with great precision. Her chemise is visible at the low neckline of her red silk velvet dress; filling in the neckline at the center is a small piece of fabric called a partlet (Van Buren and Wieck 168). In addition to the triangular partlet at the center, of black velvet, there is a gorget (Van Buren and Wieck 305) of transparent linen that covers her shoulders and is pinned to the chemise with a gold pin. The dress is trimmed in a flat grey fur, which reappears at the turned-back cuffs and at the hemline, suggesting that it was used to line the dress entirely. Her headdress (Fig. 9), her most important accessory, is an example of the turret style of this decade. Her hair has been gathered into a cylindrical mound and covered with a fine linen or silk hairnet called a crispin (Van Buren and Wieck 302) which has been embroidered with pearls and circular elements that might be red silk, or even rubies. A metallic-embroidered ribbon trims the edges of the crispin and a strip of it extends from the top of the turret to curve around her ear. There is also a wire bisecting her ear, that might connect to the wire that is curved back at the center front to run up to the top of the turret. These ribbons and wires help to stabilize the structure and anchor the fine linen veil that covers the turret, and her forehead.

Fig. 8 - Petrus Christus (Flemish, 1410-1475). Portrait of a Female Donor, ca. 1455. Oil on panel; 41.8 x 21.6 cm (16 7/16 x 8 1/2 in). Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1961.9.11. Samuel H. Kress Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 9 - Petrus Christus (Flemish, 1410-1475). Detail of Portrait of a Female Donor, ca. 1455. Oil on panel; 41.8 x 21.6 cm (16 7/16 x 8 1/2 in). Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1961.9.11. Samuel H. Kress Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown (French). The Arrival of a Princess, Grandes Chroniques de France, ca. 1458. Manuscript. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, BNF MS fr. 6465, fol. 338v. Source: Gallica

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (French). Detail from the Heures de Pierre II duc de Bretagne, 1456. Manuscript. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, BMF MS lat. 1159, fol. 18. Reproduced in Van Buren and Wieck, p. 183. Source: Worldcat

The Grandes Chroniques de France (Fig. 10), a manuscript with some miniatures attributed to Jean Fouquet, court painter to King Charles VII, shows similar styles worn by a princess and her ladies-in-waiting. They all wear low-cut dresses with contrasting trimming and partlets filling in the neckline. The ladies wear taller versions of the turret. The wires running up to the top, keeping the linen veils in place, create a ridge, and the impression that the turret is split or cracked in the center, an effect that has been described as a “cleft cylinder” (Van Buren and Wieck 182). Interestingly, the princess in this scene does not wear the turret, or any headdress at all, save for a crown. Her golden hair flows freely down her back. Her dress, however, is trimmed with ermine, long associated with royalty (Scott 156), and she has a very, very long train. Unlike princesses and queens, fashion-conscious women who did not have ladies-in-waiting must have struggled with their trained dresses; in this decade we begin to see them carrying their trains over one arm (Fig. 11), revealing an under-dress or skirt.

Women in northern Europe are rarely seen wearing any outer garments like the houppelande, which is an increasingly rare word in the clothing inventories and other documents of the time (Van Buren and Wieck 178). All-enveloping mantles and capes, necessary for warmth especially with such low necklines, did exist, but they are rarely seen in art. They would have been similar to the mantles worn by the Queen of Sheba in figures 4 and 5.

The most important development of the 1450s in women’s fashion was the evolution of the turret into an even taller, pointier conical structure. It reaches its classic form at the end of the decade, covered in black fabric with a fine linen veil draped over it and hanging from the top, as seen in figure 12. It must be acknowledged that the popular name for this headdress is hennin, but that term, if it is used at all, should be applied to the horn-shaped headdresses that caused boys in the 1420s to jeer at women with the cry used by shepherds herding sheep, “au hennin, au hennin” (Van Buren and Wieck 317-318). The turret, which appeared in the late 1440s, decidedly replaced horn-shaped headdresses by the mid-1450s and reached even greater heights by the end of the decade (Van Buren and Wieck 180). While it was certainly remarkable, we should also take note of other changes in the late 1450s, seen in figure 12: the low neckline is wider, allowing space for a broad necklace, and the excess length of the dress is lifted up at the sides and tucked under the arm. In this scene depicting the temptation of St. Bertin, a monk who lived in Carolingian times, this characteristic gesture of the fashionable woman of the 1450s reveals her true nature; she is a devil in human form and has a serpent’s tail.

Fig. 12 - Simon Marmion (French, c.1425-1489). Detail from Scenes from the Life of St. Bertin, 1459. Oil on panel; 58.5 x 146.4 cm. Berlin: Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen, 1645A. Source: SMB

Fashion Icon: ISABELLE DE BOURBON (1434-1465)

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (Flemish). Portrait d'Isabelle de Bourbon, seconde femme de Charles le Téméraire, morte en 1465, 16thc. copy of 15thc. original. Oil on panel; 52 x 32 cm. Lille: Musée des Beaux-Arts, P 1527. Source: RMN France

Nevertheless, her marriage to Charles almost didn’t happen, because her father balked at the terms demanded for her dowry, and the groom’s mother, Isabella of Portugal, wanted an English princess and alliance for her son. Philip the Good’s will overcame all obstacles, and the cousins, both twenty years old, were married at Lille on October 30, 1454 (Vaughan 342). Eight days later Isabella of Portugal, who remained on good terms with her new daughter-in-law, threw a banquet for them (Putnam 65). Like the rest of the Burgundian court, the couple traveled frequently throughout the year around the duchy’s territories, but they spent the most time in the northern-most frontier of Holland and Zeeland, where Charles acted as governor on his father’s behalf (Vaughan 342). The marriage was a happy one, with Charles going so far as to remain faithful to his wife, something that was highly unusual at that place and time (Putnam 65). In 1457, Isabelle gave birth to their daughter, Mary of Burgundy (Putnam 83).

Isabelle was the second-highest-ranking woman at the Burgundian court, second only to her mother-in-law the Duchess, who turned sixty years old in 1457. Rogier van der Weyden’s portrait of the Duchess at the start of this decade, now at the Getty Center, shows her wearing a dress of gold-brocaded velvet trimmed with ermine. She continued to fulfill her duty to present a magnificent appearance, but she did not keep up with fashion change. In the portrait she wears the horn-shaped “pair of temples” headdress that was old-fashioned by the 1450s. Shortly after her granddaughter’s birth, disappointed that her influence over her husband and his policies had waned, Isabella retired to a convent “and rarely returned to the world or took part in its ceremonies during the remainder of her life” (Putnam 90). Thus it fell to Isabelle to preside at court and showcase the latest fashions. In the two known portraits of her, both later copies of lost originals, she wears the high turret headdress. Figure 1 also shows a red silk velvet dress trimmed with brown fur, its wide, low neckline filled in with a black velvet partlet that matches the fabric covering her turret. Black velvet was also used to cover the wire that anchors the turret, visible as a semi-circle at the center of her hairline. A delicate gold and silver necklace, with the Burgundian motif of the flaming flint, is another up-to-date accessory.

Menswear

Men’s undergarments during the 1450s continued to be a linen shirt and a pair of linen drawers, both visible in one of Piero della Francesca’s Legend of the True Cross frescos (Fig. 1), where a man who has been digging has unlaced his doublet (called the farsetto in Italy) (Herald 211), and hose (calze) in other to move more freely. The hose were a pair of leggings, like the doublet made by a tailor to fit a particular man (Herald 216). In the fresco we can see the strip of linen at the top of the hose, through which eyelets would be worked, to lace each legging to the hemline of the doublet. Since the doublet was quite short, and the hose were two separate pieces, the underwear would be visible in the gap in between, both in the front and at the back, as seen in another scene in the fresco cycle (Fig. 2). There each legging of the hose is of a different color, a practice called parti-coloring that derived from heraldry. A garment or accessory could be parti-colored (adogato in Italian) with no particular heraldic significance, however (Herald 209). Hose were usually made of cut woven wool, which has natural elasticity (Evans 48, Frick 167). The doublet could be made of wool or silk (Frick 160). The doublet in figure 1 has a seam around the waistline and attached basques, the flaring pieces that form the “skirt” of the garment. By contrast, the pink doublet in figure 2 is shorter and has no basques; the red laces hanging from the sleeves would be attached to the shoulder pieces of a suit of armor (Herald 216). Regardless of the type of doublet, the garment would be lined in linen to ensure a smooth fit. Doublets generally had full upper sleeves and fitted lower sleeves, in the “Lombard” style, which were also seen in women’s dresses. The man in figure 1 wears a simple linen bonnet to absorb perspiration as he works, and black leather shoes. Some historians claim that it in this decade that peasants and urban working-class men first began to wear doublets and hose, abandoning the loose-fitting tunics of the Middle Ages, still seen in figure 1 in womenswear (Piponnier and Mane 87).

Fig. 1 - Piero della Francesca (Italian, c.1415-1492). Detail from The Finding of the True Cross, 1452-66. Fresco; 336 x 747 cm. Arezzo: Cappella Maggiore, San Francesco. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 2 - Piero della Francesca (Italian, c. 1415-1492). Detail from the Legend of the True Cross: The Battle Between Heraclius and Chosroes, 1452-66. Fresco; 336 x 747 cm. Arezzo: Cappella Maggiore, San Francesco. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 3 - Giovanni di ser Giovanni Guidi (Italian, 1406-1486). Detail of the Adimari Cassone, 1450s. Tempera on panel; 88.5 x 303 cm. Florence: Galleria dell'Accademia. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 4 - Piero della Francesca (Italian, c. 1415-1492). The Legend of the True Cross: Procession of the Queen of Sheba; Meeting of the Queen of Sheba with King Solomon, 1452-66. Fresco; 336 x 747 cm. Arezzo: Cappella Maggiore, San Francesco. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (French). Detail from the Grandes Chroniques de France, ca. 1458. Manuscript. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, BNF MS fr. 6465, fol. 166v. Source: Gallica

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (French). Detail from the Grandes Chroniques de France, ca. 1458. Manuscript. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, BNF MS fr. 6465, fol. 165v. Source: Gallica

In the Adimari Cassone painting, we can see an array of outer garments that could be worn over the basic garments of doublet and hose. Most of the young men at the far right (Fig. 3) wear the giornea, the sideless cape that was worn full-length by women (Herald 218). Men’s giorneas generally stopped at the knee; in Italy it was common to belt the front panel of the garment only, leaving the back to hang freely (Scott 148). The giornea could be of wool or silk, with a contrasting lining that would be revealed as the man moved. The man at the extreme far right is the only one wearing a different outer garment – the cioppa, the Italian equivalent of the houppelande of northern Europe. Unlike the draped giornea, the cioppa is a tailored garment with long sleeves; this one has been belted at the waist, and as this scene suggests, it is becoming rare among fashion-conscious young men in this decade. Among older men, however, it persists, as seen in figure 4. In Italy long, flowing garments were thought to lend gravitas to older men. In Florence, a long cioppa in red wool, as worn by the man at the far left, was the mark of a politically active man (Frick 174). The man to his right wears a black cioppa, under a fourth layer of clothing – the mantello, the mantle that was also worn by women. This green mantello in lined in a pinkish red; the man wears it turned up onto his right shoulder, in the alla togata style, alluding to the drapery of the ancient Roman toga (Herald 57).

In northern Europe, where fashion radiated from the courts of Burgundy and France, men’s outer garments were growing ever shorter during this decade. Full-length houppelandes are still seen, as in figure 5, but they are increasingly formal, and rare, as is the word houppelande in contemporary documents (Van Buren and Wieck 178). The knee-length version, called the haincelin (Van Buren and Wieck 306), which had dominated the 1440s, has shortened further, so that it barely covers the torso in the 1450s. At a loss for a consistent name for this garment, some historians refer to it as the “gown” (Van Buren and Wieck 178). Others retain the word houppelande but point out that it is either very long, or very short, as in figure 5 (Evans 60). Some features of the garment, long or short, continue from the previous decade, such as “pipe pleats” cinched at the waistline and width at the shoulders created by pleating the caps of the sleeves and supporting them on the interior with cushions called maheutres (Van Buren and Wieck 311). In northern Europe as in Italy, men had the option of wearing leather-soled hose and foregoing shoes, but even the tips of the hose were stiffened with strips of wood or bone, like the pointy shoes that were called poulaines (Van Buren and Wieck 314). Figure 6 shows a group of men arriving at a moated castle. Their abbreviated houppelandes are well adapted for riding, as are their high leather boots, but the extremely pointed toes seem to be driven by fashion.

Men’s headgear during this decade included draped chaperons, called cappucios in Italy (Figs. 3 & 4), which were smaller than they had been in earlier decades (Herald 212). The young men of Florence wore them with the long trailing end, called the beccheto in Italy (Herald 212) and the cornet in the north (Van Buren and Wieck 300), hanging freely or tucked into a belt; in France and Burgundy the cornets were used to fling the chaperon over the shoulder (Fig. 5). Indoors, men wore caps, including skullcaps that hugged the head, and tall caps that mimicked the conical turrets of women (Fig. 4). Outdoors, hats with narrow brims had tall, puffed crowns in Italy (Fig. 3) and lower, rounded crowns in northern Europe (Fig. 6). The chapel à bec was a traveling hat with a wide brim in the front and a pointy crown, seen in northern Europe (Van Buren and Wieck, 298). An example is worn by the King being welcomed at the castle gate in figure 6, who has added his crown on top. Thanks to Italian influence, this decade also saw the end of the Burgundian “bowl” haircut, in favor of longer hair that can be seen covering the ears, escaping from caps and hats.

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Giovanni di ser Giovanni Guidi (Italian, 1406-1486). The Adimari Cassone, 1450s. Tempera on panel; 88.5 x 303 cm. Florence: Galleria dell'Accademia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

References:

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume in the West. New York: Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/440897519

- Evans, Joan. Dress in Medieval France. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/939659457

- Frick, Carole Collier. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes and Fine Clothing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62133195

- Herald, Jacqueline. Renaissance Dress in Italy, 1400-1500. London: Bell & Hyman, 1981. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/492385048

- Piponnier, Françoise and Perrine Mane. Dress in the Middle Ages. Tr. by Catherine Beamish. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/888880339

- Putnam, Ruth. Charles the Bold, Last Duke of Burgundy, 1433-1477. New York: G.P. Putnam, 1908. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1120814728

- Scott, Margaret. Fashion in the Middle Ages. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/756230586

- Van Buren, Anne and Roger S. Wieck. Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/742330843

- Vaughan, Richard. Phillip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy. Vol. 3 of The Dukes of Burgundy. Woodbridge [UK]: Boydell Press, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1040841568

- Witthoft, Brucia. “Marriage Rituals and Marriage Chests in Quattrocento Florence.” Artibus et Historiae 3 (1982), no. 5: 43-59. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/887233421

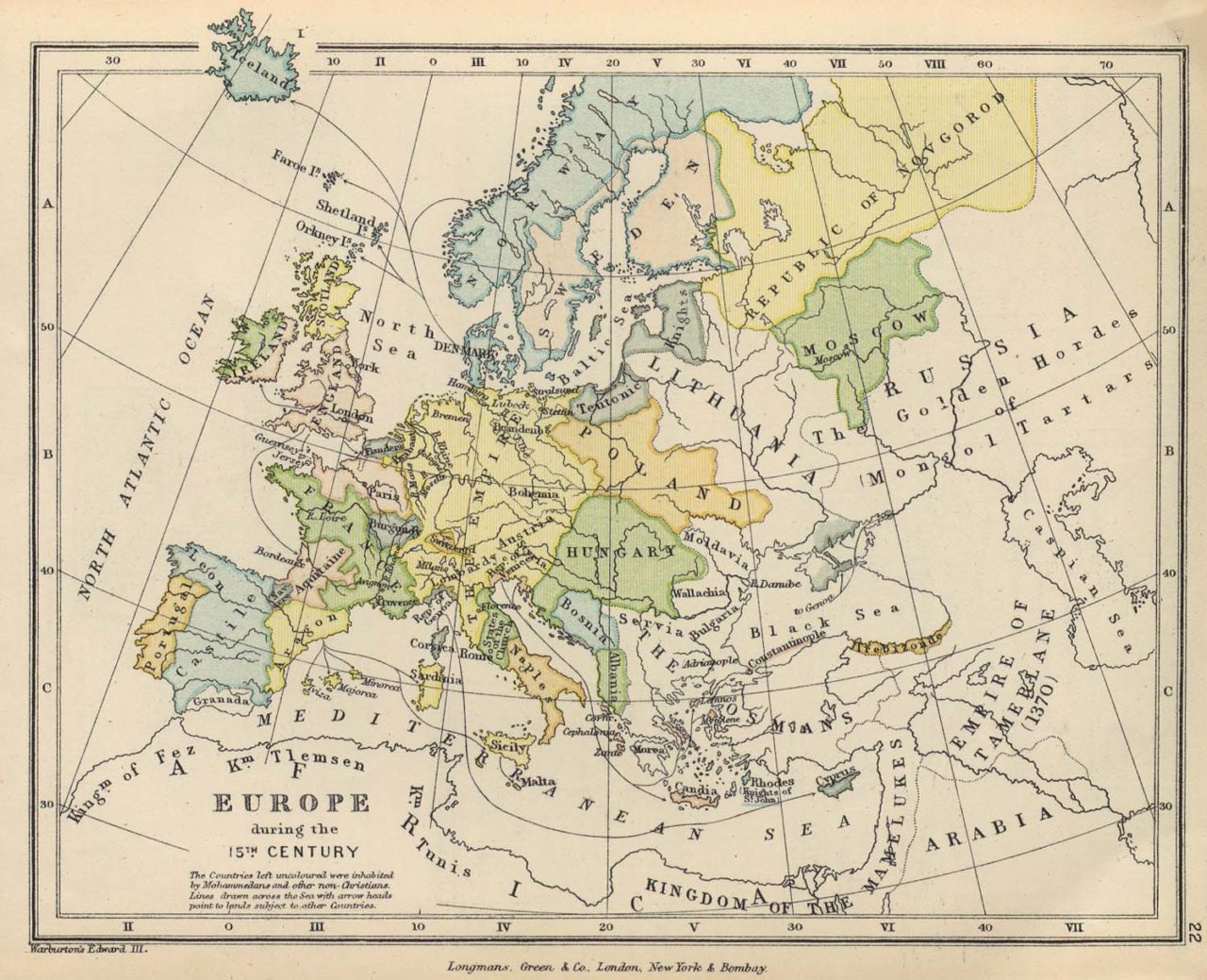

Historical Context

Europe during the 15th Century. Source: University of Texas Libraries

Events:

- 1453 – Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks

- The 1450s – Sable, lynx and other exotic furs become fashionable, replacing squirrel furs such as Miniver and vair. Ermine remains the prerogative of royalty. Women’s hair is pulled back from forehead and covered by a caul (small bag worn over a bun at the back of the head) or a crespine (mesh net). Fashionable women shave their foreheads and eyebrows. In warmer Italy married women wear their hair long, braided, in loose knots, and uncovered. Brocade becomes a luxury fabric as weaving techniques improve. The best fabric comes from Italy with Chinese, Indian, and Persian motifs reflecting increased trade with these countries.

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 15th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.