“Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving,” on view at the Brooklyn Museum, displays a collection of her personal belongings, including clothes, cosmetics, accessories, medical devices, and paintings, allowing the audience to imagine themselves in the shoes of Kahlo.

“F

rida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving,” on view at the Brooklyn Museum, is the largest American exhibition in ten years devoted to the iconic Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo. The exhibition is the first in the United States to display a collection of her personal belongings, including clothes, cosmetics, accessories, and medical devices, alongside her paintings. As these personal artifacts reveal, Kahlo often crafted her appearance and public identity to reflect her cultural heritage and political beliefs. A streetcar accident in 1925 left Kahlo in a lifetime of pain, necessitating her to wear corsets and leg braces, included in the exhibition. “Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving” brings attention to the personal experiences of Kahlo’s life, allowing the audience to better understand her art and to begin to imagine themselves in the shoes of Kahlo.

The first room of the exhibition introduces Kahlo’s family background and ethnic heritage. Born to a German father and a Mexican mother of Spanish and Native American (mestiza) descent from Oaxaca, Mexico, Kahlo explored her identity by frequently depicting her ancestry as binary opposites in her art (Fig. 1). Although Kahlo never visited the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a municipality in the southeast of Oaxaca, Kahlo incorporated the traditional Tehuana style in her wardrobe. The Museo Frida Kahlo describes the elements of the signature Tehuana dress on Google Arts and Culture (Fig. 2):

“The Tehuana dress is the pure representation of that meeting – the geometric focus on the heavily adorned upper body, the short square chain stitch blouses and the gender political statements that the dress implies. Frida and the Tehuana come together in a perfect union of identity, beauty and design.”

The Tehuana dress consists of the upper garment, the huipil, and a long colorful skirt, which covers much of the body. A huipil is a loose-fitting blouse, traditional in Mexico and Central America, composed of cotton and elaborate embroidery motifs on necklines, sleeve openings, and hem (Fig. 3). The huipil was regularly worn by Kahlo likely because of the effects it would bring–its geometric, short square construction helped her to look taller and avoided discomfort when seated. Alba F. Aragón in Uninhabited Dresses: Frida Kahlo, from Icon of Mexico to Fashion Muse (2014) explains the symbolic purpose of the huipil:

“The Tehuana’s design qualities further reinforce that impression: the unfitted huipil does not suggest a sensual, perishable body of curves and hollows. Instead, its geometry adorns an absent, thus impenetrable, body, in an apparent refusal of West’s brand of feminine seduction and the masculine gaze it implies.” (523)

Fig. 1 - Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907-1954). The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas), 1939. Oil on canvas; 171.9 x 171.9 cm (67-11/16 x 67-11/16 in). Mexico City: Museo de Arte Moderno. Acquired by the INBA directly from the author in 1947, assigned to the MAM on December 28, 1966.. Source: fridakahlo.org

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown. Cotton Mazatec huipil, hand-embroidered and appliqued; plain floor-length skirt, unknown. Cotton. Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archives. Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. Source: The Brooklyn Museum

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown. Cotton huipil with machine-embroidered chain stitch; printed cotton skirt with embroidery and holán (ruffle), unknown. Cotton. Museo Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archives. Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. Source: The Brooklyn Museum

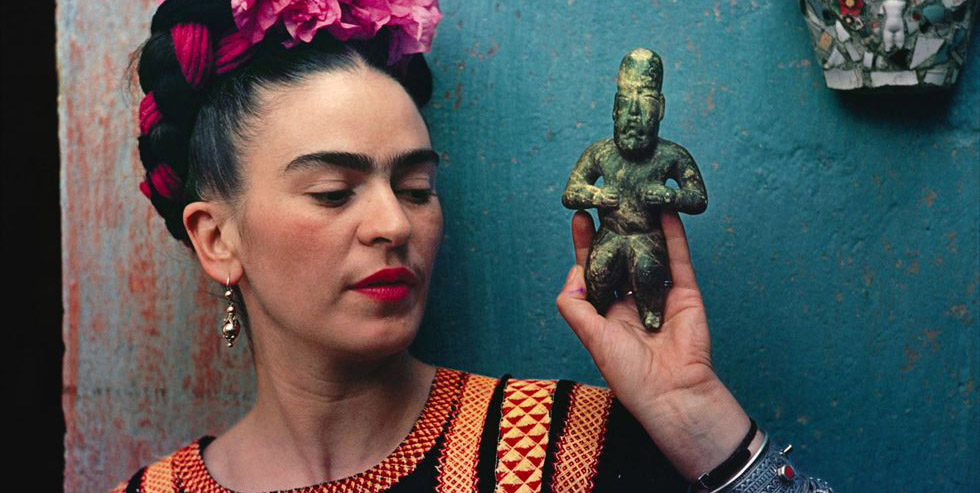

Fig. 4 - Nickolas Muray (American, 1892-1965). Frida on Bench, 1939. Carbon print; 45.5 x 36 cm (18 x 14 in). Nickolas Muray Photo Archives. Courtesy of Nickolas Muray Photo Archives. Source: The Brooklyn Museum

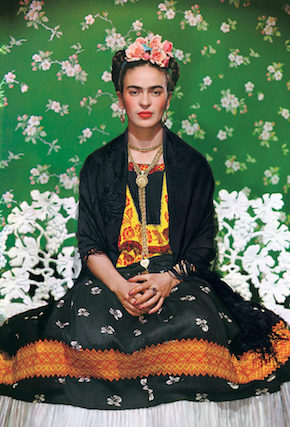

Fig. 5 - Nickolas Muray (American, 1892-1965). Frida Kahlo in Blue Satin Blouse, 1939. Nickolas Muray Photo Archives. Courtesy of Nickolas Muray Photo Archives. Source: V&A Museum

Frida Kahlo stylized her Tehuana dress with the Mexican rebozo, a long rectangular fringed shawl, draped about her shoulders (Fig. 4) and a massive string of Aztec beads about her throat. Her hair was also frequently braided and beribboned in the Tehuana style (Fig. 5). Tehuana dress held a privileged place in the iconography of Mexican identity because of its close association with the Zapotec women of Tehuantepec and their allegedly matriarchal community (Aragón 534). Thus by adopting this dress, Kahlo asserted her anti-colonialist position, as well as her identity of being distinctly Mexican and the exotic “other.” In other words, Kahlo made nationalist statements with the adaptation of traditional indigenous attire, illustrating the cultural vitality of post-revolutionary Mexico. Kahlo was also greatly influenced by socialism, ultimately joining the Mexican Communist Party. Kahlo’s roots in Oaxaca, post-revolutionary constructions of national identity, and the history of the Zapotecs guided her self-fashioning.

Fig. 6 - Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907-1954). Plaster corset, painted and decorated by Frida Kahlo, unknown. Plaster. Mexico City: Museo Frida Kahlo. Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. Source: The Brooklyn Museum

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown. Prosthetic leg with leather boot, unknown. Red leather with red grosgrain ribbon and embroidered in silk thread with chinese motifs; two metallic bells hanging from a salmon-colored ribbon. Mexico City: Museo Frida Kahlo. Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. Source: Google Arts and Culture

Fig. 8 - Florence Arquin (American, 1900-1974). Frida Kahlo, 1951. Gelatin silver print; 25.4 × 20.3 cm (10 × 8 in). New York: Throckmorton Fine Art. Source: Time

Opposite to a row of mannequins in ensembles that Kahlo wore, the gallery floor presents some of her decorated medical accessories, particularly adorned with paintings and cascabeles (a small bell in Spanish). Due to the serious injuries of her spine, Kahlo was required to wear orthopedic corsets made of leather, steel, and plaster (Fig. 6). In addition to this, her lower right leg and foot had to be amputated due to gangrene in 1953. Kahlo beautified her medical accessories by hand-painting emblematic images, fusing embroidered fabric panels, and tying tinkling bells on them (Fig. 7). Aragón details that on her corset, she painted a “red hammer and sickle” (527), indicating her commitment to Communism (Fig. 8).

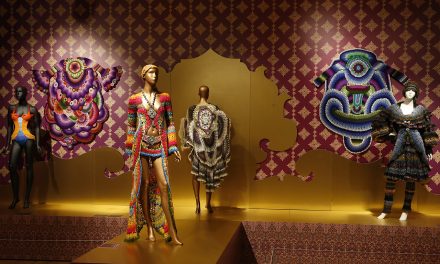

Fig. 9 - Ricky Rhodes (American, 1988-). At left, a white shawl paired with a skirt with a Chinese pattern., unknown. Source: The New York Times

Aragón also describes that the boot worn over her prosthetic leg was enhanced with “embroidered Chinese dragon motif and tiny bells” (527). Kahlo often integrated her Tehuana style dress with certain features of ethnic garments from Guatemala and China as well. For example, within the collection of ensembles displayed in the exhibition, a custom-made, heavy silk fabric skirt with a deep hem formed from a length of finer silk embroidered with Chinese motifs demonstrates her interest in other cultures (Fig. 9). These adornments attest to her creative and joyful approach to life, even as she was afflicted with pain.

“Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving” sheds light on long unseen aspects of the artist’s life, as most of her personal items were locked away at her home, the Blue House (La Casa Azul), at the instruction of her husband, Diego Rivera. Examining examples of Kahlo’s vibrant wardrobe, we now may see how she constructed her own image, influenced by her complex cultural heritage, political outlook, and experience of disability. “Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving” is on view at the Brooklyn Museum from February 8 to May 12, 2019. The museum encourages visitors to purchase their tickets online in advance.

Visit the Brooklyn Museum website for more information: “Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving”

References:

-

“Appearances Can Be Deceiving.” Google Arts & Culture. Accessed April 12, 2019. https://g.co/arts/rKCSYFASQnUPcnvn6.

-

Aragón, Alba F. “Uninhabited Dresses: Frida Kahlo, from Icon of Mexico to Fashion Muse.” Fashion Theory 18, no. 5 (November 1, 2014): 517–49. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174114X14042383562065.