OVERVIEW

Men’s fashion of the 1530s was dominated by the broad-shouldered silhouettes made iconic by King Henry VIII. Women’s fashion showed greater regional variation, with Italian women establishing trends that would soon spread to the rest of Europe in the second half of the century.

Womenswear

In Italy

In the early 1530s, one finds dress in Italy continuing as it had at the end of the 1520s, with low-cut bodices creating broad shoulder lines extended by bulbous upper sleeves, sometimes with the chest left bare (Figs. 1-2) but often filled in by an embroidered chemise (Figs. 3-8). Gowns are made of sumptuous silk satins and velvets that are variously striped (Figs. 1, 2, 6), embroidered (Figs. 2, 5), slashed and puffed (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 7), or ornamented with bows (Fig. 8).

Italian women often wear or carry gloves (Figs. 3, 6), which were “now part of the wardrobe of all well-to-do people,” but also zibellinos, or sable pelts with jeweled heads (Figs. 6-8) (Davenport 499). As François Boucher notes in A History of World Costume in the West (1997): “The balzo (roll of gilt openwork) is the usual head-dress” (220). The large bulbous headdress is also sometimes referred to as a capigliara; first popular in the 1520s, it becomes smaller over the course of the decade.

Several unusual features to point out include the saffron yellow chemise or partlet (rather than the more typical white linen) in Bartolomeo Veneto’s Portrait of a Lady in a Green Dress (Fig. 3), which is ornamented with red embroidery. Margherita Paleologo (Fig. 4) wears a black dress of particular complexity in construction, as it is “created from interlaced bands of black fabric (perhaps a heavy silk) edged with gold over a pale crimson undergown” (Royal Collection Trust). Isabella d’Este (Fig. 5) has a lynx fur asymmetrically draped over one shoulder.

Fig. 1 - Lorenzo Lotto (Venetian, 1480-1557). Portrait of a Woman inspired by Lucretia, ca. 1530-33. Oil on canvas; 96.5 x 110.6 cm. London: National Gallery, NG4256. Bought with contributions from the Benson family and the Art Fund, 1927.. Source: National Gallery

Fig. 2 - Titian (Venetian, 1488-1576). La Bella, ca. 1536. Oil on canvas; 100 x 75 cm (39.3 x 29.5 in). Florence: Palazzo Pitti. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 3 - Bartolomeo Veneto (Venetian, 1502-1555). Portrait of a Lady in a Green dress, 1530. Oil on oak panel; 85.9 x 67.6 cm (33 7/8 x 26 5/8 in). San Diego: Timken Museum of Art, 1979:003. Source: Timken Museum

Fig. 4 - Giulio Romano (Italian, 1499-1546). Portrait of Margherita Paleologo, ca. 1531. Oil on panel; 115.3 x 91 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 405777. Source: RCT

Fig. 5 - Titian (Venetian, 1488-1576). Isabella d'Este (1474-1539), ca. 1534-36. Oil on canvas; 102.4 x 64.7 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 83. Source: KHM

Parmigianino’s portrait of Antea (Fig. 6) captures a new trend for the decorative wearing of aprons, as Milia Davenport explains in The Book of Costume (1948):

“Towards the end first half XVIc., narrow, pleated, decorative aprons began to appear in rich bourgeoise costume in N. Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Flanders and parts of France…. The apron is worn with a short-waisted bodice and full skirt, which is banded horizontally; or it is the apron with his banded when the skirt is finely pleated.” (499)

Camilla Gonzaga (Fig. 7), wife of Pier Maria de Rossi (see Fig. 5 below), with whom she had nine children, wears the “characteristic Venetian bodice, long and pointed in front, pointed but short behind, is often cut extremely low and is fat-bodied” (Davenport 496). Both Camilla Gonzaga and Eleanora Gonzaga (Fig. 8) wear chemises with standing collars with ruffled edges that will evolve into ruffs in the second half of the century. As Davenport remarks, Eleanora Gonzaga, the Duchess of Urbino:

“With her Italian turban… wears the Italian gown from which the rest of Europe, through Catherine de’ Medici, will develop its standard costume of the second half XVIc.” (498).

Fig. 6 - Parmigianino (Italian, 1503-1540). Antea (Portrait of a Young Woman), ca. 1530-35. Oil on canvas; 136 x 86 cm (53.5 x 33.8 in). Naples: Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, inv.Q 108. Collezione Farnese. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 7 - Parmigianino (Italian, 1503-1540). Camilla Gonzaga, Countess of San Secondo, and her Sons, 1535-37. Oil on panel; 128 x 97 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P000280. Source: Prado

Fig. 8 - Titian (Venetian, 1488-1576). Portrait of Eleanora Gonzaga, 1538. Oil on canvas; 114 x 102.2 cm (44.8 x 40.2 in). Florence: Uffizi Gallery. Source: Wikipedia

In France

While one would assume the Queen of France would embody French fashion trends, Eleanora of Austria (Fig. 9) defied that expectation when she married François I (see Fashion icon, 1520-1529). As Anna Reynolds explains in In Fine Style (2013), Eleanora

“maintained elements of her Spanish style of clothing as a deliberate and politically motivated attempt to preserve her Habsburg identity at the French court. In her portrait by van Cleve, the hairstyle and shape of the fur sleeves can be considered particularly Spanish.” (194)

The square-cut gown bodice with a slight rise in the center (typical of France) is made of a beautiful cloth-of-gold brocade and edged in pearls and gemstones (lavish like the dress of her husband). Her sleeves are fuller than was typical in France and are paned with the chemise puffed out in the gaps between brooches; unusual hanging white fur oversleeves drape from her shoulder.

Fig. 9 - Joos van Cleve (Netherlandish, 1485-1540). Eleanora, Queen of France (1498-1558), ca. 1530. Oil on oak; 35.5 x 29.5 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 6079. Source: KHM

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown (English, 16th century). Anne Boleyn, ca. 1533-1536. Oil on panel; 54.3 x 41.6 cm (21 3//8 x 16 3/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 668. Purchased, 1882. Source: NPG

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish, 16th century). Portrait of a Young Woman, ca. 1535. Oil on wood; 26.7 x 21 cm (10 1/2 x 8 1/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.7.32. The Jules Bache Collection, 1949. Source: The Met

Fig. 12 - Ambrosius Benson (South Netherlandish, 1495-1550). Portrait of Anne Stafford, ca. 1535. Oil on panel; 40.6 x 34 cm (16 x 13 3/8 in). St Louis Museum of Art, 154:2003. Museum Purchase by exchange, and funds given by Mr. and Mrs. John Peters MacCarthy in memory of Cornelia Peters Harms. Source: SLAM

Fig. 14 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Jane Seymour, ca. 1536-37. Oil on oak; 65.5 x 47 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 881. Source: KHM

In England

More typical French style elements can be seen, ironically, in the portrait of Anne Boleyn (Fig. 10), who served as a lady-in-waiting to Mary Tudor, Queen of France (see Fashion Icon, 1510-1519). Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII (see Fashion Icon below), became Queen of England in 1533 and brought French fashion trends to the English court, among them the characteristic headdress, the French hood. Her hood is particularly ornate as a “goffered gold gauze border rests on the smooth curve of the hair” (Ashelford 37). Anne’s reign saw the increasing adoption of the French hood at the English court. This can be seen in the ca. 1535 portrait of a young woman (Fig. 11), who some believe to be Mary I, daughter of Catherine of Aragon and future Queen of England. As both portraits attest: “Square-cut décolletage was usual throughout the sixteenth century, and the rule from the 1530s” (Cunnington 55). Anne Stafford, lady-in-waiting to Anne Boleyn, also wears a version of the French hood, though her red satin kirtle sleeves with the bottom seam open and the chemise puffed out are more typically English.

Queen Jane Seymour (Fig. 13), third wife to Henry VIII, who married her in 1536 after beheading Anne, returned to more safely English modes, reverting back to the gabled hood. As Jane Ashelford explains in A Visual History of Costume: The Sixteenth Century (1983):

“Jane wears the final version of the English hood, a style in which the right half of the material was folded or twisted into the shape of a whelk-shell and then secured on top of the head; the remaining half of the material was allowed to fall behind the shoulder. The frontlet and tucked-up lappets are now shorter in length.” (color plate 20)

Her red velvet gown has a square-cut bodice and her large turned back cuffs or oversleeves are covered in a fine network of gold cord. Her kirtle, made of silver brocade, is visible through the inverted V-front opening of her gown. Her kirtle sleeves have open seams at the bottom, where they are closed with broaches and her chemise, now with intricate blackwork cuffs, is puffed out in the gaps. The stiffness of the silhouette likely reflects a shift in construction and understructure, as Hill explains:

“By the 1530s, though, the padding evolved into the busk, a torso panel made of layers of linen stitched or pasted over reinforcements of whalebone, wood, horn, or metal. The busk was inserted into the front of the bodice compressing the breasts and smoothing the torso into an inverted cone shape. (Later the term ‘busk’ was used synonymously for corset in contemporary writings.)” (378)

The construction of such gowns was more complicated than it appears as they were not all in one piece like dresses today. This is suggested, as Ninya Miklaila and Jane Malcom-Davies point out in the Tudor Tailor (2006), by the “row of pins down the side of her bodice. Her veil is pinned up on one side.” (43)

Fig. 15 - Remigius van Leemput (Netherlandish, d. 1675). Henry VII, Elizabeth of York, Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, 1667 (based on 1537 original). Oil on canvas; 88.9 x 99.2 cm. Hampton Court Palace, RCIN 405750. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 16 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Lady Ratcliffe, ca. 1532-43. Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, brush and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper; 30.1 x 20.3 cm. London: Kensington Palace, RCIN 912236. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Thanks to a rare full-length dynastic portrait (Fig. 15) that includes Jane alongside Henry VIII and his parents, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, we can observe that gown skirts began to shift in shape; they were “trained until 1530 and occasionally until 1540…. Between 1530 and 1540 skirts became ground length all round” (Cunnington 64). Jane like Anne before her became a fashion trendsetter at court as Holbein’s sketch of Lady Ratcliffe (Fig. 16) testifies “for a period in the 1530s some fashionable women at court chose to pin up one long black side lappet, with the other hanging down to the shoulder” (Reynolds 65). We saw the same asymmetric pinning in Holbein’s 1536 portrait of Jane (Fig. 14).

Fig. 17 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Anne of Cleves (1515-1557), ca. 1539. Oil on parchment mounted on canvas; 65 x 48 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, INV. 1348. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 18 - Lucas Cranach the Elder (German, 1472-1553). The princesses Sibylla (1515-1592), Emilia (1516-1591) and Sidonia (1518-1575) of Saxony, ca. 1535. Oil on basswood; 62 x 89 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 877. Source: KHM

In Germany

Henry VIII’s fourth wife, Anne of Cleves (Fig. 17), was German and is said to have brought a few German trends to the English court, among them the wearing of multiple rings on a hand (Hill 381). The marriage was unconsummated and short-lived (though this Anne survived its ending), allegedly because Henry found her appearance unpleasing. Davenport describes her dress in the portrait Holbein was commissioned to paint in advance of the wedding:

“The lower sleeves are funnel-shaped, like her skirt, which was described as ‘without a trayne [train] after the Dutche fassyon,’ at a period when English ladies’ gowns, almost alone, retain them. The tucker or partlet and the cuff-bands of the shirt are not of the Spanish embroidery seen so far, but of cut-work; this antedates lace, which in fact grew out of cutwork; lace has been made since XVc. and will be common by XVIIc.” (432)

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s triple portrait of the princesses of Saxony (Fig. 18) reveals other typical Germanic dress elements. Gown sleeves remain narrow (left), sometimes with paned rolls or open seams (center), or paned with regular cuffs cinching them in (right). The low-cut bodice is sometimes filled only with a heavy gold chain or perhaps a very transparent partlet (center). As Davenport notes, “As the waistline becomes lower, the embroidered band of the plastron remains unchanged in width and position: the wide opening of the bodice is laced across the white shirt below” (392). Very full skirts are created through tight pleating at the waist. Two of the sisters wear incredibly thin gloves that are pinked to reveal their rings below. Their headdress styles are also typical:

“In Germany, hats were wide brimmed and pinned into place at an angle over cauls, or hairnets of gold thread…. A profusion of ostrich plumes was often set in a flower-petal arrangement all around the brim.” (Hill 381)

Bracelets and earrings were rare in Germany as they could not usually be seen given that long sleeve cuffs almost reached the knuckles and the elaborate headdresses typically hid at least one ear.

Fashion Icon: Henry VIII, King of England

Fig. 1 - Joos van Cleve (Netherlandish, d. 1540). Henry VIII (1491-1547), ca. 1530-35. Oil on panel; 72.4 x 58.6 cm. Hampton Court Palace, RCIN 403368. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 2 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Portrait of Henry VIII, ca. 1537-47. Oil on canvas; 239 x 134.5 cm (94.09 x 52.95 in). Liverpool: Walker Art Gallery, WAG 1350. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 3 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Henry VIII of England, ca. 1537. Oil on panel; 28 x 20 cm. Madrid: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Inv. no. 191 (1934.39). Source: Thyssen-Bornemisza

Henry VIII (1497-1547) is perhaps best known for having six wives, three of whom we discussed above: Anne Boleyn (Fig. 10), Jane Seymour (Figs. 14-15) and Anne of Cleves (Fig. 17), but he also masterfully manipulated his own image to project power and authority. The image of Henry VIII in the popular imagination has been set by Hans Holbein’s famous portraits (Figs. 2-3), which depict him in middle age when he had grown quite stout, but as a young man he was considered quite attractive. Indeed, as Maria Hayward records in Dress at the Court of King Henry VIII (2007):

“Sebastian Giustianian, the Venetian ambassador, writing on 10 September 1519… described Henry (aged 29) in the following terms: ‘he is much handsomer than any other sovereign in Christendom; a great deal handsomer than the King of France; very fair, his whole frame admirably proportioned.’” (2)

Henry was in constant competition with François I, King of France (see Fashion Icon, 1520-1529), throughout his reign, having copied François’ beard around 1515. At their famous meeting at the Field of the Cloth of Gold (Fig. 4), the men daily tried to outdo the other in the extravagance of their dress:

“The first day saw Henry in a gown of thickly pleated cloth of silver ribbed with gold, and a doublet of rose velvet. His cap was black velvet encircled with rubies, emeralds and pearls with a white plume. His horse had tissue of cloth of gold over russet velvet, with the gold cut into waves edged with gold to signify the English lordship of the sea.” (De Marly 32)

Many descriptions of Henry’s clothes like this one have been passed down and royal wardrobe records provide a detailed picture of what exactly he owned. For example, Henry VIII’s 1536 Wardrobe Account describes a pair of hose and stockings:

“It’m for making a paire of hoose, upper stocked with carnacion-coloured satten, cutte and embrowdered with golde and also lyned with fyne white clothe, with two paire of nether stockis, the one paire skarlette, and the other paire blacke carsye.” (Cunnington 35)

The visual record is more limited, however, as Hayward explains in Rich Apparel: Clothing and the Law in Henry VIII’s England (2009):

“The images of Henry VIII that Holbein created in the 1530s are so familiar that it is easy to gain the impression that there is a lot of visual evidence for the king’s wardrobe. However, in reality, there are only seven portrait types of the king and only two of these were created by Holbein…. These portraits confirm the use of sable and other dark furs, which were reserved for royal use, along with scarlet velvets, cloth of gold and cloth of silver. All of these were very expensive but there were no instances of the purple silks that the legislation gave him the express right to wear.” (154)

Joos van Cleve’s early 1530s portrait of Henry (Fig. 1) shows him in a cloth-of-gold doublet that is slashed across the chest and sleeves. The neckline of the doublet is low and straight, while his jeweled shirt fits closely at the neck and is puffed out through the gaps created by the slashes. Ashelford comments:

“Henry’s love of jewels and desire for flamboyant display increases as he rapidly puts on weight until the massive surface are of his dress is broken up with slashing and encrusted with applied decoration…. The gown has a wide sable collar that spreads across the shoulders and its sleeves are embroidered with seed pearls.” (34)

Holbein’s full-length (Fig. 2) and half-length (Fig. 3) portraits of Henry VIII show him in very similar dress. His doublet is cut closer to the neck and the slashes (Fig. 2) and open seams (Fig. 3) are smaller than in the van Cleve portrait, though the shirt is still puffed through. His jerkin has a deep U-shaped opening and full skirt and he wears an extremely broad-shouldered gown with a sable revers. His codpiece is prominent, and he carries a dagger and wears a sword. Ashelford describes the effect:

“Male dress was intended to enhance and exaggerate the wearer’s masculinity and this was achieved by creating a massive chest and wide shoulder. Henry adopts the aggressive and dominant stance that was an essential part of this image.” (35)

The tight fit of his white stockings suggest they might be knit; knitted hose began to be made in England c. 1530 (Cunnington 37). The Order of the Garter is tied below his left knee and his duckbill shoes have square toes and slashed uppers. Henry passed many sumptuary laws, or laws regulating dress, during his reign; among them, “An order was issued in Henry VIII’s reign, limiting the width of the toe to six inches” (Cunnington 38).

The black bonnet with halo brim topped with an ostrich feather and adorned with pearls and gemstones closely resembles that worn by François I (see Fig. 7 below and Fashion Icon 1520-1529). Like François I and his own wives discussed above, Henry VIII set the fashion in England and ensured through sumptuary laws that he would always be the best dressed.

Fig. 4 - British School (16th century). The Field of the Cloth of Gold, ca. 1545. Oil on canvas; 168.9 x 347.3 cm. Hampton Court Palace, RCIN 405794. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Menswear

Discussion of Henry VIII above has already introduced the key features of English menswear of the 1530s, so only a few more examples will be added. Holbein’s courtship tondo portrait of Simon George of Cornwall shows the standing collar ornamented with blackwork and the narrow opening of the gown and jerkin that reveals the red doublet below that became common. Doublets began fitting around the neck in the 1530s (Cunnington 17). The Cunningtons describe the changes in the shirt:

“By 1530 this was a standing collar edged with a turn-down collar or a frill, the origin of the ruff. The standing collar increased in height as with the doublet. Embroidery in black-work or coloured silks to shirt necks and wrists was very common…. Shirt Sleeve Frills [1530s] began to appear below the doublet sleeve, at the wrist, in the 1530s.” (17, 21)

George wears a black bonnet, fashionably tilted, and ornamented with ostrich feather, hat badge and golden flowers and other forms like that favored by Henry VIII.

Henry VIII’s illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy (Fig. 2) is shown very unconventionally in a portrait miniature wearing only his shirt, which lays open down his chest, and a linen nightcap with blackwork embroidery. At the opposite end of the scale, an unknown man in red thought to be English (Fig. 3) is shown in an unusual full-length, life-size portrait. His shirt is also decorated with blackwork embroidery at the collar, cuffs and down the front, which is visible thanks to the narrow opening of his jerkin, which is also parted by his large, slashed codpiece. His red hose are paned and loose-fitting, paired with red stockings and slashed red velvet shoes that conform to the natural contours of the foot (unlike Henry VIII’s duckbills above). He wears a sword and dagger suspended from his belt, along with a large gold tassel. The Royal Collection Trust describes his gown, whose upper sleeves are paned and closed by aiguillettes:

“These lower sleeves are decorated with ‘pullings out’ – diaphanous fabric woven with gold thread is pulled through slashes in the layer above. Like most gowns at this date, this one appears to be of velvet. The sheen on the large collar, turned back to reveal the lining of the gown, suggests it is possibly lined with a fabric woven with metal thread. The most expensive fabrics were often reserved for linings.”

In the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire in this period encompassed Spain, the Netherlands, parts of Germany, Italy and Austria, as well as colonies in North and South America, so it is difficult to speak of a single style. Charles V (Fig. 4) was its Emperor and he adopted many Spanish trends as Boucher explains:

“the neck gradually became enclosed to give a high, tightly fastened collar with a purely Spanish, rather prudish character. In the portrait of Charles V by Titian we find one of the first examples of this high collar, and of tight upper stocks.” (229)

In the portrait by Titian, Charles also wears a large gown with sable revers and puffed-out shoulder sleeve, with an attached hanging sleeve below. His doublet sleeves are paned; his hose is very tight-fitting and narrowly pinked. His white stockings are paired with white shoes that are slashed and follow the natural shape of his foot.

Hill describes the impact of these Spanish trends:

“The transition of men’s clothing styles of the mid-sixteenth century was influenced by the Spanish. Garments encased and distorted the figure. Trouser-like upper stocks, a padded codpiece, and jackets with wide lapels and oversized sleeves exaggerated the masculine silhouette and physical proportions.” (356)

Fig. 1 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Simon George of Cornwall, 1536. Oil on oak; 31 x 32.4 cm. Frankfurt: Städel Museum, 1065. Source: Städel Museum

Fig. 2 - Lucas Horenbout (Flemish, 1490-1544). Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset (1519-1536), ca. 1533-34. Watercolour on vellum laid on card; 4.4 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 420019. Source: RCT

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (German/Netherlandish). Portrait of a Man in Red, ca. 1530-50. Oil on panel; 190.2 x 105.7 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 405752. Source: Royal Collection

Fig. 4 - Titian (Venetian, 1490-1576). Emperor Charles V with a Dog, 1533. Oil on canvas; 194 x 112.7 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P000409. Source: Prado

Fig. 5 - Parmigianino (Italian, 1503-1540). Pietro Maria Rossi, Count of San Secondo, 1535-38. Oil on panel; 133 x 98 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P000279. Source: Prado

Fig. 6 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Charles de Solier, Sieur de Morette, 1534-35. Oil on panel; 92.5 x 75.5 cm (36.41 x 29.72 in). Dresden: Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, AM-1890-PS01. Source: Wikipedia

Pier Maria Rossi (Fig. 5), served at the court of Charles V and mirrors the trends seen thus far, with the broad masculine silhouette and newly prominent hose, which in his case are white and slashed to reveal the white lining below. There is a companion portrait of his wife above (Fig. 7). Rossi’s codpiece is exceptionally prominent given the color contrast with his dark jerkin and robe; indeed,

“Now the codpiece was a tailored accessory—cut and sewn into a projecting horn shape, padded, and accented with ribbons, bows, pinking, and assorted other decorative treatments.” (Hill 355)

In France

Charles de Solier (Fig. 6), who served as gentilhomme de la chambre to François I (Fig. 7), was also ambassador to England on several occasions, which is when he had his portrait painted by Holbein. The result is an impressive and imposing frontal portrait in conformance with masculine ideals of the day. His doublet, jerkin and gown are all in dark fabrics, making his face and the bright white of his shirt particularly striking. His doublet sleeves are paned with the gaps between them closed by golden aiguillettes. One gloved hand holds his dagger and a large golden tassel hangs from his waist.

Fig. 7 - Titian (Venetian, 1488-1576). François I, 1538. Oil on canvas; 109 x 89 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, INV 753. Source: Ministère de la Culture

Fig. 8 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). The Ambassadors, 1533. Oil on oak; 207 x 209.5 cm. London: National Gallery, NG1314. Source: National Gallery

Titian’s softer profile portrait of François I (Fig. 7) does not create the same impact. His scarlet satin doublet has long slashes down the chest and a scalloped standing collar. The sleeves are also slashed and he wears a dark gown and black bonnet topped with an ostrich feather.

Holbein’s famous painting The Ambassadors (Fig. 8) depicts two different French envoys to the English court, Jean de Dinteville, seigneur de Polisy, and Georges de Selve, Bishop of Lavaur.

Jean de Dinteville wears a scarlet satin doublet like François I’s and a broad-shouldered gown lined with lynx fur. Davenport comments on this choice:

“Light, spotted lynx, with which his gown is collared and lined, has become a favorite fur; lines of fur were much used at the seams of the upper puffed sleeve, in both male and female costume.” (430)

Fig. 9 - Lucas Cranach the Elder (German, 1472-1553). Lukas Spielhausen, 1532. Oil and gold on beech; 50.8 x 36.5 cm (20 x 14 3/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1981.57.1. Bequest of Gula V. Hirschland, 1980. Source: The Met

Fig. 10 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Hermann von Wedigh III (died 1560), 1532. Oil and gold on oak; 42.2 x 32.4 cm (16 5/8 x 12 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 50.135.4. Bequest of Edward S. Harkness, 1940. Source: The Met

Fig. 11 - Bronzino (Italian, 1503-1572). Portrait of a Young Man, 1530s. Oil on wood; 95.6 x 74.9 cm (37 5/8 x 29 1/2 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.100.16. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. Source: The Met

In Germany and Italy

Lukas Spielhausen (Fig. 9) was a member of the electoral court of Saxony. He wears a low-cut doublet with red pinked strips edged with gold cord and an ample black gown. But the most remarkable feature is his strongly horizontal beard and mustache, as Davenport notes: “Moustaches and short beards at their greatest square width; hair short; hats, caps and embroidered cauls of rich, dignified men” (396). Holbein painted a German merchant, Hermann von Wedigh III (Fig. 10) who, by contrast, is clean shaven, but similarly soberly attired in rich fabrics.

Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man (Fig. 11) continues the Florentine trends first seen in 1520-1529, but with new severity, here dressed mostly in black. His doublet is slashed all over, but, as the lining is also black, the effect is subtle. His hat is decorated with golden aiguillettes as are the joins between his doublet and hose and his codpiece. The high standing collar of his white shirt has a slight frill that will soon evolve into a ruff. He is dressed quite differently from the men in other countries we’ve seen, but is, in fact, the forerunner of what is to come in men’s fashion.

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Microfashion of the 1530s continued to reflect adult trends. As Hill wryly remarks: “Even the hose of prepubescent boys were fashioned with the exaggerated shape of the a padded codpiece” (355). Edward VI, son of Henry VIII (see Fashion Icon above) and Jane Seymour (Fig. 14 above), is dressed much like his father with cloth-of-gold doublet sleeves and a red velvet jerkin ornamented with gold cord and tied with golden aiguillettes. His red velvet bonnet decorated with ostrich feather and again with aiguillettes closely resembles his father’s. Davenport notes that the use of aiguillettes here and by the gentry generally was to elevate this “enormously popular hat” to higher status (431).

Two portraits of the young Maximilian of Austria (Figs. 2-3) show the high collars and cropped hair typically seen on young boys (Davenport 496). The bald head of the toddler John, brother of Maximilian, comically contrasts with his lavish adult clothing.

Fig. 1 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Edward VI as a Child, ca. 1538. Oil on panel; 56.8 x 44 cm (22 3/8 x 17 15/16 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1937.1.64. Andrew W. Mellon Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 2 - Jakob Seisenegger (Austrian, 1505-1567). Portrait of Maximilian of Austria (1527-1576), Aged Three, 1530. Oil on panel; 43 x 34.4 cm. The Hague: Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, 271. Source: Mauritshuis

Fig. 3 - Jakob Seisenegger (Austrian, 1505-1567). Maximilian and his younger brothers Ferdinand II and John, 1539. Oil on canvas; 40 x 60 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, GG_8191. Source: Kunsthistorisches

Jan van Scorel’s portrait of a young student (Fig. 4) offers a rare look at the dress of a non-royal individual. Jane Huggett and Ninya Mikhalia describe his outfit in The Tudor Child (2013):

“This middle-class schoolboy is plainly but respectably dressed in black with a red knitted cap. He wears a shirt of finely-gathered linen fastened with two thread buttons and loops. Over this, he has a double with a standing collar cut in one piece with the body. His coat has pleated skirts and an opening covered by a front-fastening flap with points on either side of the chest. It also has an integral standing collar.” (29)

The rosy-cheeked Eleanor (Fig. 5) was the eighth child of Archduke Ferdinand of Austria (before his election as Holy Roman Emperor) and his wife Anna of Bohemia and Hungary, which explains her more Germanic style of dressing with narrow pink sleeves ornamented with black velvet bands and transparent puffs of fabric.

Jan Gossaert’s portrait of a young princess, perhaps Dorothea of Denmark (Fig. 6) shows her in a square-cut bodice with a slight rise at the center, with large cream sleeves depicting interlocking blue knots and ornamented with hundreds of pearls. Her French hood style headdress is edged again with many pearls—not an outfit for romping around on the playground!

Fig. 4 - Jan van Scorel (Netherlandish, 1495-1562). Portrait of a Young Student, 1531. Oil on panel; 46.5 x 35 cm. Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans, 1797. Aankoop / Purchase: 1864. Source: Boijmans

Fig. 5 - Jakob Seisenegger (Austrian, 1505-1567). Archduchess Eleanor (1534-1594), Duchess of Mantua as a two-year-old, ca. 1536. Oil on basswood; 34 x 27 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 872. Source: KHM

Fig. 6 - Jan Gossaert (Netherlandish, active 1508; died 1532). A Young Princess (Dorothea of Denmark?), ca. 1530-32. Oil on oak; 38.2 x 29.1 cm. London: National Gallery, NG2211. Source: National Gallery

References:

- Ashelford, Jane. A Visual History of Costume: The Sixteenth Century. London: Batsford, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/748457696.

- Boucher, François, Yvonne Deslandres, and John Ross. A History of Costume in the West: With 1188 Illustrations, 365 in Colour. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/443676264.

- Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Cunnington. Handbook of English Costume in the Sixteenth Century. London: Faber and Faber, 1954. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/362761.

- Davenport, Millia. The Book of Costume. New York: Crown Publishers, 1948. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/922657048.

- De Marly, Diana. Fashion for Men: An Illustrated History. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1985. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/752978274.

- “German/Netherlandish School, 16th Century – Portrait of a Man in Red.” Accessed June 21, 2019. https://www.rct.uk/collection/405752/portrait-of-a-man-in-red.

- Hayward, Maria, ed. Dress at the Court of King Henry VIII. Leeds: Maney, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/997437672.

- ———. Rich Apparel: Clothing and the Law in Henry VIII’s England. Farnham, England: Ashgate, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/990796848.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950.

- Huggett, Jane, Ninya Mikhaila, Jane Malcolm-Davies, and Michael Perry. The Tudor Child: Clothing and Culture 1485 to 1625. Hollywood: Quite Specific Media, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/925431430.

- Mikhaila, Ninya, and Jane Malcolm-Davies. The Tudor Tailor: Reconstructing 16th-Century Dress. Hollywood: Costume and Fashion Press, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/937528534.

- Reynolds, Anna. In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/824726826.

- Royal Collection Trust. “Giulio Romano (Rome c. 1499-Mantua 1546) – Portrait of Margherita Paleologo.” Accessed June 21, 2019. https://www.rct.uk/collection/405777/portrait-of-margherita-paleologo.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1530-1539

Rulers:

- England: Henry VIII (1491-1547)

- France: Francis I (1515-1547)

- Spain: Charles I (1516-1566)

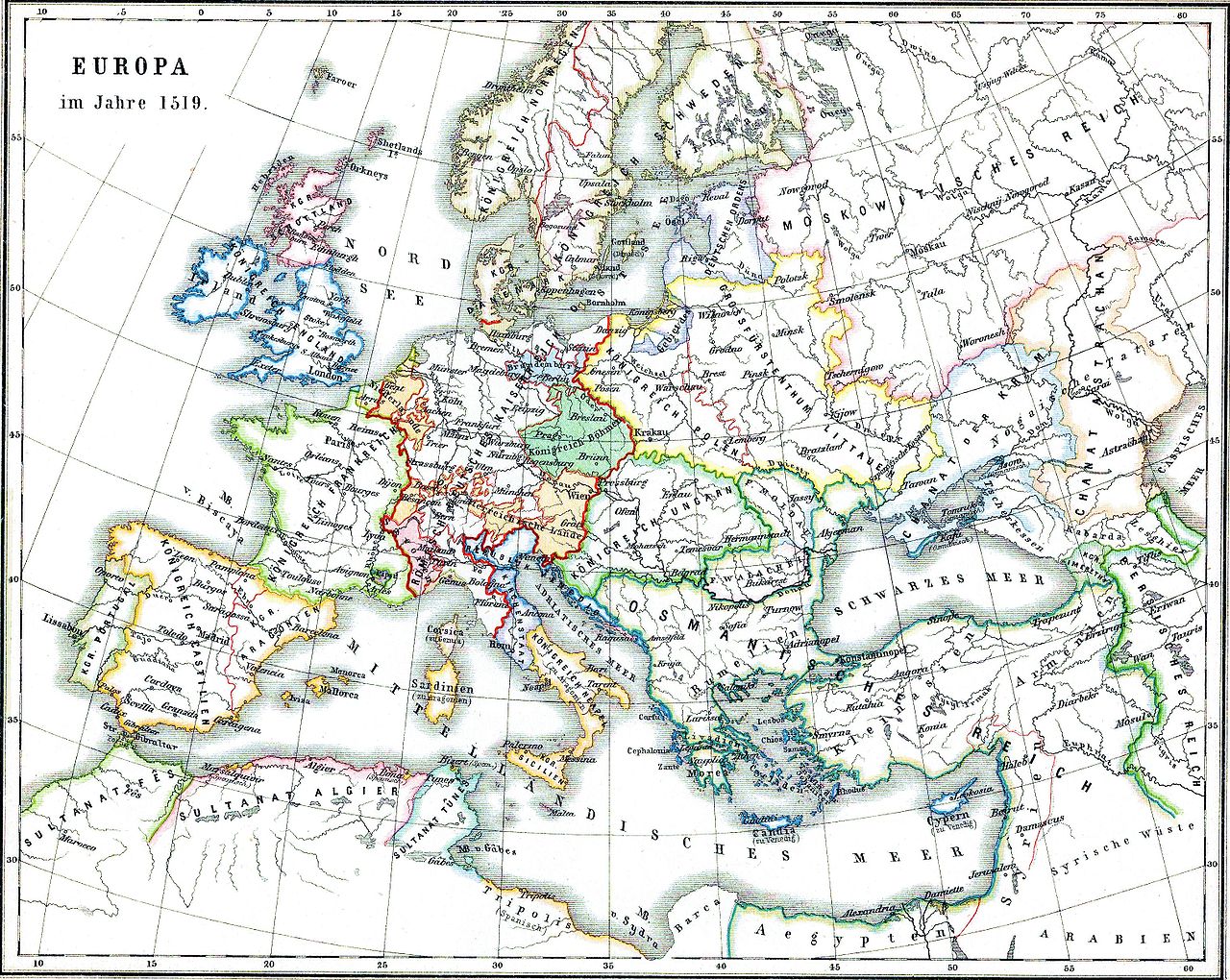

Map of Europe, 1519. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Events:

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 16th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.