OVERVIEW

Women in the 1570s believed more was more, loved intense decorative effects, and adopted some influences from menswear. Men’s dress was quite curvilinear, with a padded belly, small waist, and large bulbous melon hose at the thighs.

Womenswear

As Jane Ashelford remarks in Dress in the Age of Elizabeth I (1988): “During the 1570s dress became highly inventive and offered women a wider range of styles and decoration to choose from” (11).

Queen Elizabeth used dress politically and dressing well and in keeping with the latest styles was essential at the English court. A portrait by Nicholas Hilliard shows a favorite style of the Queen (Fig. 1), whose taste favored intense decorative exuberance; as Ashelford remarks: “The proliferation of applied decoration is typical of the Elizabethan’s pre-occupation with pattern and avoidance of plain surfaces” (82). The portrait also features a preferred color scheme: “The Queen loved to contrast lustrous white pearls against her favourite colours of black, silver and gold.” (Ashelford 87)

A portrait of an unknown Englishwoman (Fig. 2) shares the black, white and gold color palette and the all-over surface decoration, as well as mirroring the queen’s neckline and lace-edged, closed figure-8 ruff. The chemises of both women are decorated with blackwork embroidery, which is quite visible due to the low, sloping/square-cut neckline. A late sixteenth-century chemise in the Met’s collection has extensive blackwork on it (Fig. 3). The floral designs are quite similar to those seen on a sheer embroidered partlet in another British portrait (Fig. 4). Notably that woman has embroidery not only on the sheer partlet, but also on the chemise visible below, creating quite a busy visual effect.

A 1578 portrait of Lady Philippa Coningsby (Fig. 5) shows that the ruff will continue to grow in size over the course of the decade (achieving peak width ca. 1585). Lady Coningsby has blackwork embroidery on her chemise and white embroidery on her sheer partlet, in addition to methodically pinked sleeves.

Fig. 1 - Associated with Nicholas Hilliard (English, 1547-1619). Queen Elizabeth I, ca. 1575. Oil on panel; 78.7 x 61 cm (31 x 24 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 190. Purchased, 1865. Source: NPG

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. Unknown woman, formerly known as Mary, Queen of Scots, ca. 1570. Oil on panel; 96.2 x 70.2 cm (37 7/8 x 27 5/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 96. Purchased, 1860. Source: NPG

Fig. 3 - Maker unknown (Italian). Chemise, late 16th century. Silk, linen, metal thread. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 41.64. Source: The Met

Fig. 4 - British School. Portrait of an Unknown Lady (once called 'Catherine Parr', and then 'Catherine Vaux, Lady Throckmorton'), 1576. Oil on panel; 54.5 x 45.5 cm. Alcester: Coughton Court, 135556. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 5 - George Gower (English, 1530-1596). Lady Philippa Coningsby, 1578. Oil on panel; (37 x 27 5/8 in). Indianapolis Museum of Art, 56.107. James E. Roberts Fund. Source: IMA

Fig. 6 - George Gower (English, 1540-1596). Elizabeth Littleton, Lady Willoughby, 1573. Oil on canvas; 75.6 x 63.5 cm (29.7 x 25 in). Source: Wikipedia

Hats and hairstyles adapted to counterbalance the expanding width of the ruff and silhouette in general, as Ashelford notes:

“An increased desire for width can also be seen in the shape of the hair: it is now puffed out on both sides of the head and the jewel-encrusted bonnet that adorns the head is flatter and longer so that it balances the wider shape.” (28-29)

All of these portraits also highlight a shift in period jewelry styles, which Millia Davenport explains with reference to a portrait of Lady Willoughby (Fig. 6)

“During the reign of Elizabeth, the character of jewelry alters: jeweled collars are replaced by draped strands of pearls; and oval medallions by more elaborate pendants, showing better cut stones, increasingly naturalistic enamel work in paler colors; miniatures; cameos; mirrors; and watches of all shapes, octagonal, fat and pomander-like, or flattened. Both the form of the pendant and the spot at which it is places are now less often symmetrical. Lady Willoughby wears her enameled mermaid pendant at one side of her bodice, which is looped with strings of pearls combined with beads.” (439)

Lady Willoughby also wears a man’s style hat—another popular trend of the time:

“Interest in the hat now centers on its band. This carries the jewels formerly pinned to the under side of the brim; and from it, clusters of plumes emphasize the heightening crown. The male hat, much seen on women, is worn here, as was usual, with loose uncovered hair and a tiny reticulated cap, set on the back of the head. The hat, as well as the cap, is often worn indoors by women at this period, just as it is by men.” (Davenport 439)

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown (Continental). Queen Elizabeth I, ca. 1575. Oil on panel; 113 x 78.7 cm (44 1/2 x 31 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2082. Purchased, 1925. Source: NPG

Fig. 8 - Arist unknown. Queen Elizabeth I, ca. 1575. Oil on panel; 98 x 133 cm. Reading Museum, REDMG 1980.168.1. Source: Reading Museum

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (Italian). Robe of the Countess Dorothea Sabina, late 16th century. Silk, velvet, metallic thread. The Bavarian National Museum, Munich. Source: Bayerisches Nationalmuseum

A portrait of Queen Elizabeth (Fig. 7) shows her wearing asymmetrically draped strands of pearls, but also the menswear influence as her dress bodice appears to be modeled on man’s doublet with a center-front fastening, high collar, and very narrow skirt/peplum—now essentially a border at the edge (Ashelford 84). Counterbalancing the masculine styling, the dress is trimmed in pale orange and made with a gold floral brocade pattern on what would originally have been a darker crimson/violet ground. Contemporary critic Philip Stubbes nonetheless complained in the 1570s that “mannes apparell is, for all the worlde” (Arnold 137). Of course, as a queen ruling an empire adopting masculine dress elements likely amplified Elizabeth’s projection of power. The doublet influence is even more evident in a portrait from ca. 1575 (Fig. 8), where her dress bodice ends in pickadils at the peplum and the wings. As Ashelford remarks: “The silhouette is becoming fuller and stiffer. The width across the upper part of the body is accentuated by a tiny waist and the wing no longer projects above the sleeve” (97). Janet Arnold notes other changes in the silhouette as well in Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d (1988),

“From the late 1560s onwards the pleats at the waist were interlined and the skirt was worn over padded cotton rolls which gradually increased in size, giving a dome shape. The waistline rose slightly over the padding in the mid-1570s still keeping the point in the front.” (19)

A surviving dress in Italian fabric (Fig. 9) has similar styling, with tabs edging the doublet-like bodice. The dress still has an inverted V-shaped opening in the front to reveal a contrasting kirtle/skirt. Notably this dress has both long, loose hanging sleeves and narrow, banded tubular sleeves. Hanging sleeves like this were particularly worn in Spain as you can see in Alonso Sánchez Coello’s portrait of a lady with a fan (Fig. 10) and in his portraits of Anna of Austria (see the Fashion Icon section below). Spanish collars were particularly high on both men and women.

For further discussion of Spanish fashion, see the analysis of Anna of Austria in the Fashion Icon section below.

Fig. 10 - Alonso Sánchez Coello (Spanish, 1531-1588). Lady with a Fan, 1570-73. Oil on panel; 62.6 x 55 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P001142. Source: Prado

Fig. 11 - Alessandro Allori (Florentine, 1535-1607). Maria de' Medici, Oil on poplar. 116 x 90. Vienna: Kunsthistoriches Museum, 2583. Source: KHM

Fig. 12 - François Clouet (French, 1510-1572). Elisabeth of Austria (1554-1592), Queen of France, daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II of Austria and Infanta Maria of Spain, wife of King Charles Charles IX of France, ca. 1571. Oil on panel; 37 x 25 cm (14.5 x 9.8 in). Chantilly: Musée Condé, PE 258. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 13 - Monogrammist AC (French, active unti 1577). Sibylle de Clèves-Juliers-Berg, margravine de Burgau, before 1577. Oil on panel; 49.3 x 36.1 cm. Private Collection. Source: Wikipedia

On the other hand, Italian women preferred open collars, which flared out and stood up and framed the neck; this style would later be termed a Medici collar. You can see an example in Alessandro Allori’s portrait of Maria de’ Medici (Fig. 11); her sleeves are banded like those in the surviving dress seen above. She wears a short-sleeved overdress like a Spanish ropa, rather than the doublet-influenced fashions seen on Queen Elizabeth.

Elisabeth of Austria, Queen of France, (Fig. 12) wears the rather stiff, puffed fashions popular at the French court, with a symmetrical arrangement of her jewelry. Sibylle de Clèves-Juliers-Berg (Fig. 13) also wears symmetrically styled jewelry, with a larger figure-8 ruff and cuffs and rather high shoulder wings. The ensemble is very ordered and lavish in its use of gold embroidery; she wears a small mannish bonnet atop her head.

Mette of Münchhausen (Fig. 14) displays more traditional Germanic dress styles, including the decorative pleated white apron at front. Tight pleating is also visible in her dress and skirt as well. She wears a black velvet gollar, or shoulder cape (Brown 86).

Fig. 14 - Ludger Tom Ring the Younger (German, 1522-1584). Mette of Münchhausen, ca. 1570. Oil on pearwood; 58.1 x 38.8 cm. Hamburg Kunsthalle, 344. Gift of Consul Eduard F. Weber 1912. Source: Wikipedia

Fashion Icon: Anna of Austria, Queen of Spain

Fig. 1 - Bartolomé González after Anthonis Mor (Spanish, 1564-1627). Queen Anna of Austria, ca. 1616 (based on portrait of 1570). Oil on canvas; 108.5 x 87 cm. Madrid: Museo el Prado, P001141. Source: Prado

Anna of Austria (1549-1580) was the eldest daughter of Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor, and Maria of Spain. Anna was born in Spain, but raised in Vienna from age 4. She became Queen of Spain in 1570 at the age of 20 when she married King Philip II.

Antonis Mor is thought to have painted Anna as she traveled to Spain to be married. In the portrait (Fig. 1) she wears a white outer robe with gold embroidery, worn open to reveal a diagonally striped doublet-like bodice with a very high collar topped by a small, figure-8 ruff. Her arms are only half covered by the outer robe’s sleeves, which stop at the elbow and then hang freely behind her forearm. Her robe sleeves are attached with large reddish pink ribbons with golden points.

Another portrait by Mor (Fig. 2) shows her in an almost identical pose, complete with one hand gloved in black clutching a white handkerchief, except the color palette here is completely different as she wears a deep black outer robe and a canary yellow doublet-bodice. Her arms are free of the outer robe’s sleeves entirely, which hang loosely behind her. She wears a masculine-style black feathered bonnet encrusted with jewels.

Philip II was her maternal uncle and she had previously been engaged to his son, Don Carlos, but upon Don Carlos’ untimely death plans changed. She was Philip II’s fourth wife. Their marriage was reputed to be a happy one, with Anna described as “vivid and cheerful” (Wikipedia).

Alonso Sánchez Coello’s ca. 1571 portrait of Anna as Queen (Fig. 3) shows her in a more stiffly formal look, with her outer robe buttoned all the way up to her now larger, lace-edged ruff. The white robe is covered in gold embroidery and the surface is slashed all over. As in the first portrait, her arms are inserted only half through her robe sleeves, with the empty sleeves hanging behind.

Fig. 2 - Anthonis Mor van Dashorst (Netherlandish, 1516-1575). Anna of Austria, Queen of Spain, 1570. Oil on canvas; 161 x 110 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 3053. Source: KHM

Fig. 3 - Alonso Sánchez Coello (Spanish, 1531-1588). Anna of Austria, Queen Consort of Spain, ca. 1571. Oil on canvas; 125.7 x 101.5 cm (49.4 x 39.9 in). Madrid: Museo Lázaro Galdiano, 8030. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 4 - Alonso Sánchez Coello (Spanish, 1531-1588). Anna of Austria, 1571. Oil on canvas; 176 x 98 cm (69.3 x 38.6 in). Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, GG 1733. Source: KHM

Another Coello portrait (Fig. 4) features yet another hanging sleeve style, which became fashionable:

“In the 1570s Anna of Austria, Queen of Spain, wore an elegant black saya (gown) with white accents and lavish embroidery. The gown’s long, pointed sleeves and subtle fit earned Spanish tailors international repute.” (Brown 94)

Her dress style is also fashion forward in its use of ribbons as Davenport explains:

“Ribbon loops (which will become extremely important in XVIIc.) have come into use on the jeweled puntas which catch her skirt and great sleeves.” (466)

Anna and Philip had five children together, the youngest and only surviving son (of four) would go onto to rule Spain as Philip III. A Coello painting of 1579 (Fig. 5) shows Anna banqueting with Philip and other family and courtiers. It offers a rare rear view of dress in this period. Anna would die the next year at age 30 only eight months after the birth of her only daughter.

Fig. 5 - Alonso Sánchez Coello (Spanish, 1531-1588). King Philip II of Spain banqueting with his family and courtiers, 1579. Oil on canvas; 110 x 202 cm (43.3 x 79.5 in). Warsaw: National Museum, M.Ob.295 (73635). Source: Wikipedia

Menswear

“a peascod, was created by stiffening the front of the doublet with pasteboard or busks and heavy padding at the point of the waist. The padding was called bombast, and could be made from horsehair, flocks, rags, cotton, flax, rags [sic] and even bran.” (47)

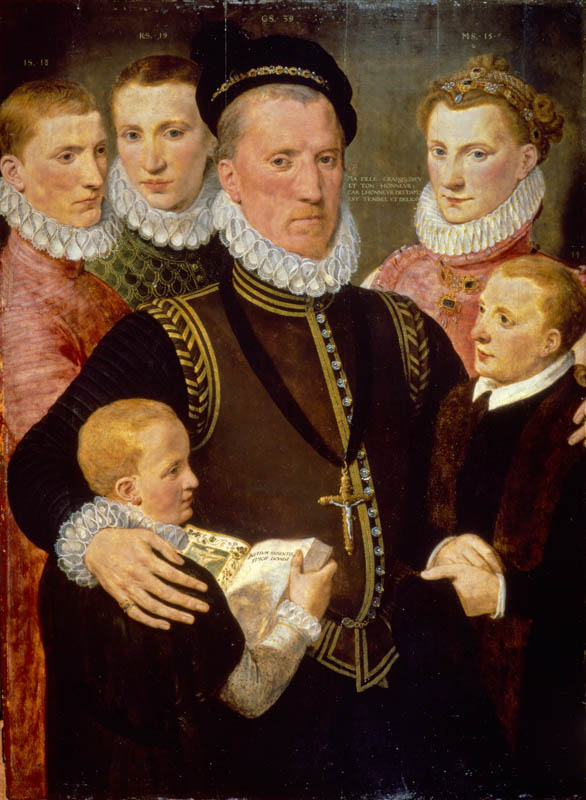

The distinctive peascod shape is visible in Frans Pourbus’s portrait of George, 5th Lord Seton and his Family (Fig. 1). Queen Elizabeth’s favorite, Robert Dudley sports an even more fashionable version in a ca. 1575 portrait (Fig. 2). As Hill points out, the belly’s protrusion was very localized:

“In the 1570s, the tailored protuberance reached such distended proportions that the garment came to be known as the peascod-belly or ‘goose-belly’ doublet. Yet the bulge was confined solely to the front of the garment. The fashion was still very much for a trim, youthful waistline despite the rotund frontal projection.” (356)

This is evident in the portrait of Dudley and also in that of Sir Philip Sidney (Fig. 3). Both men’s doublets are covered all over with slashing and the peplum/skirt of the doublet is now only a mere border, as was typical by 1575 (Cunningtons 91).

Fig. 1 - Frans Pourbus (Netherlandish, 1545-1581). George, 5th Lord Seton (about 1531-1585) and his Family, 1572. Oil on panel; 109 x 79 cm. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, NG 2275. Bequest of Sir Theophilus Biddulph 1948; received 1965. Source: National Galleries of Scotland

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown (Anglo-Netherlandish). Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, ca. 1575. Oil on panel; 108 x 82.6 cm (42 1/2 x 32 1/2 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 447. Purchased, 1877. Source: NPG

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Sir Philip Sidney, 18th century or after, based on work of ca. 1575. Oil on canvas; 115.2 x 82.3 cm (45 3/8 x 32 3/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2096. Given by Harold Lee-Dillon, 17th Viscount Dillon, 1925. Source: NPG

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Sir Thomas Coningsby, 1572. Oil on panel; 94 x 69.9 cm (37 x 27 1/2 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 4348. Purchased, 1964. Source: NPG

Fig. 5 - Cornelis Ketel (Netherlandish, 1548-1616). Sir Martin Frobisher, 1577. Oil on canvas; 211 x 98 cm (83 x 38.5 in). University of Oxford. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 6 - Maker unknown. Jerkin, 1571-1590. Leather, linen; l 67 cm (centre front); c 118 cm (chest); w 46 cm (shoulder); w 4 cm (shoulder tabs); l 59 cm (centre back). Museum of London, 57.127/1. Source: Museum of London

The Cunningtons describe a change in doublet/jerkin collars to accommodate the larger ruffs being worn:

“After 1570 the collar subsided slightly or remained high behind, curving away in front to make room for the large ruffs of the 1570s, which were worn with a forward tilt, up behind and down in front.” (90)

Ruffs are medium-sized, often arranged in a figure-8 pattern and worn closed, with the band strings tied and concealed (Cunningtons 112). There were exceptions, as in Dudley’s portrait his ruff seems to part to allow his beard to descend and Sir Thomas Coningsby’s ruff seems to be embracing a slightly anarchic spirit in its folds (Fig. 4). Sidney’s ruff (Fig. 3) is worn atop a metal gorget, which “could only be worn with civilian dress if the wearer had been on military service,” as Ashelford explains in A Visual History of Costume (93). These ruffs were now frequently separate from the shirt and tied on, rather than merely being an elaboration of the existing shirt collar. The shirt remained the foundational garment for menswear in this period.

While Dudley and Sidney’s doubets feature actual slashing and pinking (regular small slits or shapes cut into the fabric’s surface), Coningsby’s doublet illustrates that embroidery to look like slashing and pinking was also popular. Indeed, as Ashelford remarks: “Experimentation with surface decoration in male and female dress in the 1570s took on an almost trompe l’oeil form” (81). Of course, some doublets and jerkins were quite plain; for example, the leather jerkin seen in the portrait of Sir Martin Frobisher (Fig. 5) and in a similar surviving example in the Museum of London (Fig. 6). Ashelford explains the leather jerkin’s origins and fashionability in Dress in the Age of Elizabeth I:

“The leather jerkin, a military garment adapted for civilian use, was also known as the buff jerkin, as it was made of buff, an ox-hide dressed with oil. This type of jerkin, a relatively inexpensive garment went out of fashion in the mid 1570s, but remained in general use during the seventeenth century.” (47)

While Dudley and Sidney wear very full paned melon hose, with a slight codpiece visible, Frobisher wears much looser trunk hose as Davenport explains: “Full, loose, breeches (venetians) never have codpieces and usually fasten below the knee, and are finished here by picadill slashing” (441).

Frobisher’s portrait reveals another practical trend that is less frequently seen in painting of this period, namely the unbuttoning of the jerkin. While this sort of casual informality will be a hallmark of 17th-century portraiture, it is less frequently seen in the 16th century. It wasn’t merely a style choice as:

“These superimposed padded garments were terribly hot, and both men and women got relief by wearing them open to the waist. In the presence of the French ambassador, De Maisse, Elizabeth opened her gown to the navel.” (Davenport 441)

Fig. 7 - Jean de Court (French, 1530-1584). Henry III before his ascent, 1573-1574. Oil on panel; 35 × 25 cm (13.8 × 9.8 in). Chantilly: Musée Condé, PE 256. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 8 - Monogrammist LAM (French). Portrait of a Man in White, 1574. Oil on wood; 41 x 24.1 cm (16 1/8 x 9 1/2 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 32.100.119. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931. Source: The Met

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown. Miniature of Henri III, ca. 1578. Florence: Pitti Palace. Source: Les Derniers Valois

In France, Henri III (Fig. 7) embraced a particularly extravagant look and a much more buttoned up one than worn at the English court. His doublet and cloak are covered in gold embroidery or braid and his jewel-studded necklace is made of strands of pearls. Contemporary visitors to the French court attest to its status-dressing:

“The size of a courtier’s wardrobe in Paris was described by ambassador Lippomano in 1577, who said a wardrobe of 25 to 30 costumes was necessary to be esteemed rich, and a different outfit had to be worn every day.” (De Marly 33)

A small, full-length portrait of a man in white (Fig. 8) shows an elegant ensemble, with a “doublet with the sloping shoulder seen in France” (Davenport 481). Henri III is credited with pushing the ruff to new widths, as Boucher recounts:

“Possibly Henri III, always on the look-out for new fashions, was attracted by the sheer extravagance of this accessory [the ruff]. In any case, in 1578 he appeared in a starched ruff made of fifteen ells of muslin half a foot wide; this provoke the comments of the Parisians, who compared it with the platter bearing the head of John the Baptist and shouted, ‘You can tell the calf’s head by the ruff’ at courtiers who ventured out thus adorned.” (240)

A portrait miniature from ca. 1578 (Fig. 9) shows Henri III in just such a platter-sized ruff, which will become the fashionable norm in the 1580s.

Fig. 10 - Maker unknown. Doublet, 1570s. Breeches a la sevilla, stocking and cassock made of tabby silk. Private Collection. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 11 - Paolo Veronese (Paolo Caliari) (Italian, 1528-1588). Boy with a Greyhound, 1570s. Oil on canvas; 173.7 x 101.9 cm (68 3/8 x 40 1/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.100.105. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. Source: The Met

Fig. 12 - Giovanni Battista Moroni (Italian, 1520-1578). Bernardo Spini, ca. 1570. Oil on canvas; 98.5 x 197.6 cm. Bergamo: Pinacoteca dell'Accademia Carrara. Source: LombardiaBeniCulturali

A crimson doublet, breeches and stockings ensemble (Fig. 10) from this period survives, providing further evidence of the shift in silhouette—namely, the doublet having narrow sleeves and only a narrow border at the waist rather than the fuller skirt seen earlier in the century. The breeches or melon hose are bulbous as one would expect and the whole look monochromatic like that seen in the portrait by LAM (Fig. 8). A similar style of dress is seen in the unnamed Boy with a Greyhound (Fig. 11) at the Met, which also features a prominent peascod belly.

Giovanni Battista Moroni’s portrait of Bernardo Spini (Fig. 12) shows another monochromatic ensemble, though here the black of doublet, hose, and stockings is enlivened by the bright pops of white of his ruff and cuffs. The surface of his doublet is elaborately pinked. Beneath his full melon hose, he wears (rather difficult to distinguish) canions, “tight fitting extensions from the trunk hose to the knee or just below” (Cunningtons 116).

Gloves were often worn or carried; swords were a must-have accessory even for civilian dress. Shoes tended to follow the natural form of the foot and were still often decorated with slashing.

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Siblings were often dressed in quite similar fashions as that portrait and another of a man his two children (Fig. 2) by Moroni attests. While the National Gallery says the painting features his two daughters, it is also possible the younger child is a boy as boys were dressed in skirts until often the age of 4 or 5. Lady Arabella Stuart (Fig. 3) at 23 months wears a dress with shoulder wings cut into pickadils and elaborate floral embroidery on the bodice and sleeves as was popular in womenswear of the day, but is not yet wearing a ruff, like that seen on the doll she holds. The doll “may have been made to convey fashion news and then handed down as a toy” as Arnold notes in Patterns of Fashion 4 (158).

A portrait of a little girl with a basket of cherries (Fig. 4) also shows her in a simpler lace collar and wearing a coral necklace—both likely concessions to her age. Coral necklaces were popular gifts for children and were thought to confer protection onto them.

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. Three Children, 1575-80. Oil on panel; 73 x 57 cm. Private Collection. Source: Guinea pigs in art

Fig. 2 - Giovanni Battista Moroni (Italian, 1521-1579). Portrait of a Gentleman and His Two Children, ca. 1572-75. Oil on canvas; 125.3 x 98 cm. Dublin: National Gallery of Ireland, NGI.105. Purchased, 1866. Source: National Gallery

Fig. 3 - British School. Lady Arabella Stuart, later Duchess of Somerset (1575-1615), aged 23 months, 1577. Oil on panel; 75.1 x 61.5 cm. Derbyshire: Hardwick Hall, NT 1129175. Source: National Trust

Fig. 4 - Follower of Marten de Vos (Netherlandish). A Little Girl with a Basket of Cherries, ca. 1575-80. Oil on canvas; 80.4 x 52.9 cm. London: The National Gallery, NG6161. Bequeathed by Mrs Elizabeth Carstairs, 1952. Source: National Gallery

References:

- “Anna of Austria, Queen of Spain.” In Wikipedia, July 20, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Anna_of_Austria,_Queen_of_Spain&oldid=907146892.

- Arnold, Janet. Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d: The Inventories of the Wardrobe of Robes Prepared in July 1600. Leeds: Maney, 1988. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/939897963.

- Arnold, Janet, Jenny Tiramani, and Santina M. Levey. Patterns of Fashion 4: The Cut and Construction of Linen Shirts, Smocks, Neckwear, Headwear and Accessories for Men and Women c.1540-1660. Hollywood: Quite Specific Media Group, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/909294834.

- Ashelford, Jane. A Visual History of Costume: The Sixteenth Century. London: Batsford, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/748457696.

- ———. Dress in the Age of Elizabeth I. London: Batsford, 1988. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/17981612.

- Boucher, François, Yvonne Deslandres, and John Ross. A History of Costume in the West: With 1188 Illustrations, 365 in Colour. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/443676264.

- Brown, Susan, ed. Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. New York: DK Publishing, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/840417029.

- Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Cunnington. Handbook of English Costume in the Sixteenth Century. London: Faber and Faber, 1954. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/362761.

- Davenport, Millia. The Book of Costume. New York: Crown Publishers, 1948. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/922657048.

- De Marly, Diana. Fashion for Men: An Illustrated History. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1985. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/752978274.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1570-1579

Rulers:

- England: Queen Elizabeth I (1558 – 1603)

- France:

- Charles IX (1560 – 1574)

- Henry III (1574-1589)

- Spain: Phillip II (1556-1598)

1570 Map of Europe. Source: Fine Art America

Events:

- 1572 – Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre: The marriage of Margaret Valois to the Protestant Henry of Navarre leads to an attack by the Catholics upon the Protestants across France, killing thousands of Huguenots.

- 1574-89 – Reign of Henry III marked by religious civil war

- 1577 – The first clock with a minute hand appears, developed by Jost Burgi, a Swiss clockmaker.

- 1579 – The population of China reaches 60 million.

- 1570s – Introduction of the French, or “wheel,” farthingale, with a stuffed roll around the hips and a hoop with horizontal stiffeners tied around the waist that makes the skirt stick out from the body.

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 16th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.