OVERVIEW

The duchy of Burgundy, enriched by the wealth of its Flemish cities, was the leading center of fashion during the 1420s. The Duke of Burgundy’s alliance with England supported the production of the finest woolen textiles, woven in Flanders from English yarn. Merchants used their profits from manufacture and trade to rival aristocrats as the greatest consumers of Italian silk velvets and other luxuries. Throughout Europe, men dressed in black and women with tall, horn-shaped headdresses were signs of Burgundian influence.

Womenswear

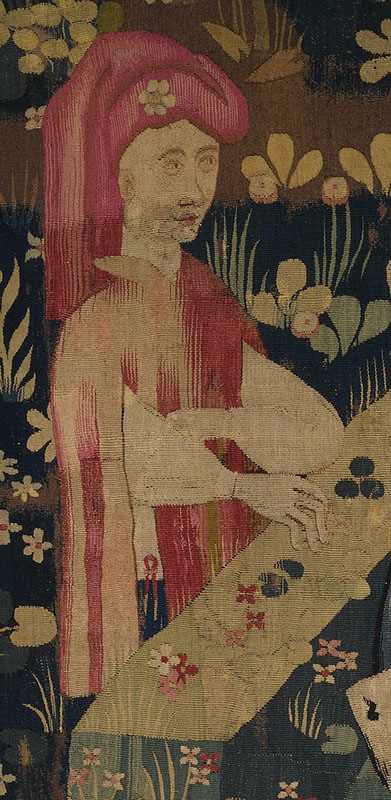

Women’s dress began with the basic undergarment, a chemise of undyed linen (Boucher 445). Over this were layered one or more côte-hardies, dresses with fitted bodices and full, flaring skirts (Van Buren and Wieck 302). The côte-hardie was typically made of wool of varying quality or, for the very rich, of silk (Piponnier and Mane 88). In the allegorical tapestry Honor Making a Chaplet of Roses (Fig. 1), the young woman in red wears a côte-hardie that laces at the right side; it has a wide low neckline and long funnel-shaped sleeves in a restrained example of a style called bombard sleeves (Van Buren and Wieck 295). Since she raises her skirt in the front in a fashionable gesture, we can see the garment underneath and her simple shoes with straps over the insteps. Her other hand points to her red-and-gold bourrelet, a headdress of padded fabric (Boucher 442). Though this area of the tapestry has been re-woven, and we cannot be sure that the bourrelet is unaltered (Cavallo 150), it has the extremely wide shape characteristic of this decade. The inscription below the figure has been interpreted as “to please my friend, I will put on this pretty hat” (Cavallo 151).

The seated figure representing Honor is more elaborately dressed in a houppelande. The houppelande, also worn by men, was an outer garment with a high neckline and long sleeves (Van Buren and Wieck 307). Women’s houppelandes were worn over the côte-hardie and typically belted at a high waistline. This example is likely made of a fine blue wool or silk. It has a wide collar of ermine, the most prestigious fur long associated with royalty, matching the turned-back ermine cuffs of the long sleeves. A second turned-down collar, probably of snow-white linen, sits over the ermine collar. The black-and-gold floral patterned undersleeves belong to the côte-hardie worn underneath; because such textiles were so precious, they were typically used sparingly. The rest of the côte-hardie, hidden under the houppelande, would likely be made of a plain wool.

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (South Netherlandish). Honor Making a Chaplet of Roses, ca. 1420. Tapestry with wool warps and wefts; 236.2 x 274.3 cm (93 x 108 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 59.85. The Cloisters Collection, 1959. Source: MMA

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French). Cluster brooch with letters spelling out "Amor", Mid-15th century. Gold, pearl, emerald, silver pin; 2.9 x 2.4 x 1.4 cm (1 1/8 x 15/16 x 9/16 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 57.26.1. The Cloisters Collection, 1957. Source: MMA

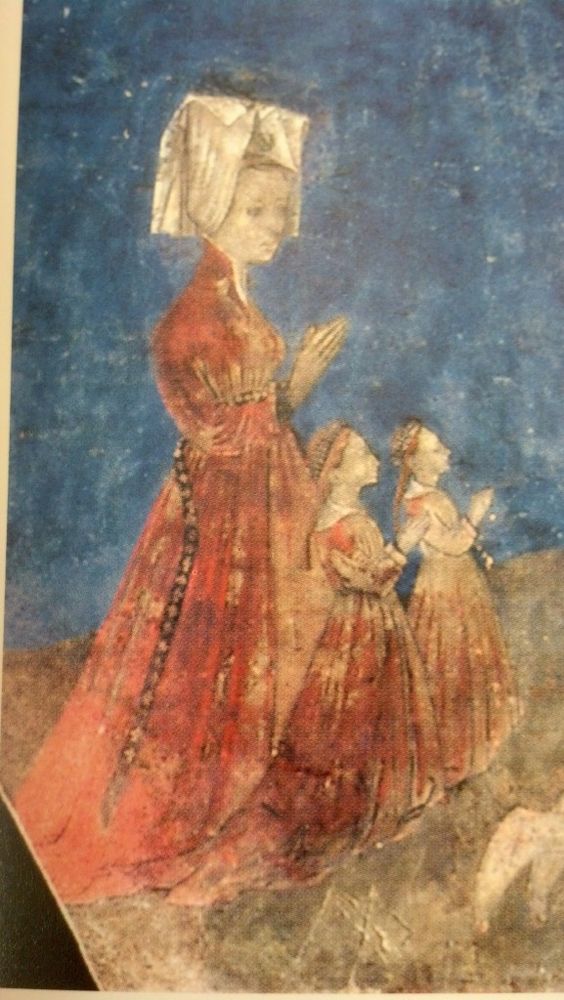

Honor’s headdress is a fine example of the style known as “a pair of temples,” in which the hair was massed into cones over the temples and held in place with hairnets and pins (Van Buren and Wieck 317-18). Although not new in the 1420s, the hairstyle grew markedly taller and wider during the decade. When topped with a bourrelet padded roll, a woman’s headdress projected upwards and outwards like a pair of horns. Honor’s bourrelet is decorated with a dozen jeweled brooches (Fig. 2). An alternative to the bourrelet can be seen in the Bedford Hours, a prayer book that belonged to Anne of Burgundy, Duchess of Bedford (Fig. 3). Two of the ladies attending a queen in ceremonial dress are dressed in houppelandes, in bright green and in red-and-gold, respectively. The lady in green wears a headdress of linen veils called huves, suspended on wires driven into the cones of hair (Van Buren and Wieck 308). An even taller and wider example is worn by a third lady, dressed in a golden côte-hardie with bombard sleeves lined in pink. Hairnets edged with narrow black trimmings, as seen here on all three ladies, was a new detail to heighten fashionable pallor. As in the tapestry we see idealized women with large, oval faces, long necks, narrow shoulders, small breasts and slightly rounded bellies.

Fig. 3 - Bedford Master (French). A hermit presents the fleur-de-lys to Queen Clotilde, detail of The Legend of the Fleur-de-lys, The Bedford Hours, ca. 1430. Parchment, illumination; 26 x 18.5 cm. London: The British Library, Add. MS 18850, fol. 288v. Source: BL.UK

For contemporaries, as for historians today, headdresses were the most notable aspect of women’s fashion during this decade. According to the Burgundian chronicler Enguerrand de Monstrelet, in 1428 a Carmelite monk named Thomas Couette travelled throughout northern France preaching against women who wore tall headdresses and attracting large crowds. Monstrelet wrote that:

“no such woman, whatever her rank, dared to be found in his presence for when he saw any he would incite all the little children …. to cry loudly after them, ‘Au hennin, au hennin!’,”

like shepherds herding their flock. Couette encouraged children to pull off the headdresses and bring them to him, “and there in front of his platform had great fires lit and all these things thrown into them” (Van Buren and Wieck 12). In relating the story of one of the century’s many “bonfires of the vanities,” Monstrelet took the cry of “hennin” and applied it as the name of the headdresses, which as we have seen were not one style but two, with a common foundation in the “pair of temples” hairstyle. Although his use of the word hennin would prove confusing to historians of fifteenth-century fashion, Monstrelet helpfully recounted the aftermath of Couette’s campaign, which was effective only:

“for a little while… [Women] followed the example of the snail, which pulls in its horns for a passer-by and when it hears nothing more thrusts them out again, for, soon after the preacher left the country they forgot his teaching and began to do the same again as before, and little by little took up their former array as grandly or more so than before.” (Van Buren and Wieck 12)

Fig. 4 - Master of Manta (Italian, Early 15th century). Braves and Heroines series: Sinope and Hippolyta, 1411-16. Fresco. Saluzzo, Italy: Castello della Manta, Sala Baronale. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 5 - Master of Manta (Italian, Early 15th century). Braves and Heroines series: Goffredo di Buglione and Delfila, 1411-16. Fresco. Saluzzo, Italy: Castello della Manta. Source: Web Gallery of Art

The influence of these extravagant headdresses, and of Franco-Burgundian fashion in general, can be seen in the frescos completed shortly after 1420 in the Castello della Manta south of Turin, which was then part of the independent duchy of Savoy. The frescos in the castle’s baronial hall depict a traditional medieval subject — the Nine Worthies from the Bible and from ancient and medieval history. Their female counterparts (Figs. 4-5) wear elements of masculine armor to denote their status as ideal heroines and are otherwise dressed in the height of fashion in houppelandes made of Italian patterned silks (Fig. 5). One figure (Fig. 4) wears a houppelande lined in gray fur with a high standing collar and full-length panels hanging from the shoulders rather than sleeves. Her cones of golden hair are covered with beaded hairnets edged with black ribbons and pearls and crowned with a red bourrelet studded with brooches. Another (Fig. 5) wears a houppelande with long bombard sleeves lined in white fur, the edges set off with a decorative cutting technique called dagging (Van Buren and Wieck 302). Her bourrelet features a padded roll covered in black fabric with dagged edges, embroidered with green leaf motifs and white pearls. This type of bourrelet was called a sella in Italy, for its resemblance to a saddle (Herald 56). Both ladies wear necklaces with hanging pendants, called carcanets, spanning their shoulders (Van Buren and Wieck 297).

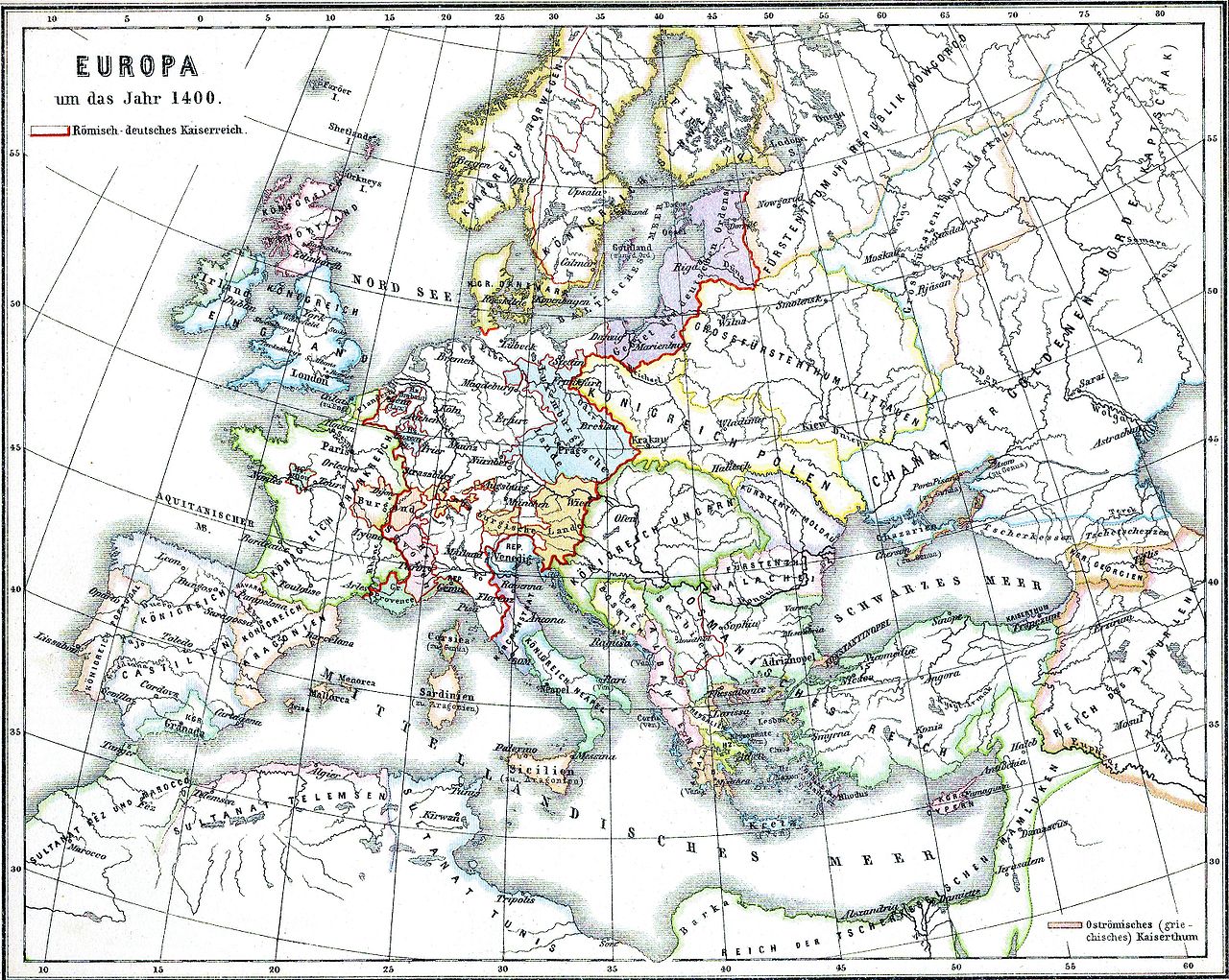

With its location just south of Burgundy, bordered by the duchy of Milan to the east and the republic of Genoa to the south, Savoy was well situated to transmit Burgundian fashions to Italy. However, under Duke Amadeo VIII the duchy enacted one of the strictest and most detailed sumptuary laws ever written. The Statutes of Savoy regulated the fabric, color, cut and ornamentation of dress for women and men in thirty-nine ranked social categories, from the family of the reigning duke to the unmarried daughters of peasants (Piponnier and Mane 84-86). The sumptuous and colorful dress seen in the Castello della Manta frescoes would have been permitted only to high-ranking nobility. The law encouraged some aspects of fashion over others; since the middle classes were not permitted to wear red, they gravitated towards black, which at the court of Burgundy was becoming the most fashionable and powerful color of all, especially in men’s fashion.

Fashion Icon: Anne of Burgundy (1404-1432)

Fig. 1 - Bedford Master (French). Anne of Burgundy, Duchess of Bedford, kneeling before St. Anne, the Virgin Mary, and Christ from The Bedford Hours, ca. 1430. Parchment, illumination; 26 x 18.5 cm. London: The British Library, Add. MS 18850, fol. 257v. Source: BL.UK

Fig. 2 - Bedford Master (French). John, Duke of Bedford kneeling before St. George from The Bedford Hours, ca. 1430. Parchment, illumination; 26 x 18.5 cm. London: The British Library, Add. MS 18850, fol. 256v. Source: BL.UK

Fig. 9 - Guillaume de Veluten (attr.) (French, died 1444). Funerary statue (gisant) from the tomb of Anne of Burgundy (d. 1432), 1432-44. White and black marble; 162 x 42 x 31 cm. Paris: Louvre, L.P. 442. Photograph by Gérard Ducher. Source: Wikipedia

Anne of Burgundy was the daughter of Marguerite of Bavaria and Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, and sister to his successor, Duke Philip III, later known as Philip the Good. She came of age in the midst of the civil war between the French royal family and their Burgundian cousins, and during a period of English ascendancy over France in the 100 Years’ War. After her father’s assassination in 1419 on the orders of the Dauphin Charles, heir to the French throne, Anne became a pawn in her brother’s efforts to forge an alliance with the English against the French (Backhouse 54-60). In 1420, Philip compelled the French King Charles VI, weakened by English military victories and hampered by mental illness, to condemn the assassination and disinherit the Dauphin (Backhouse 55). The Treaty of Troyes concluded that year called for the King of England, Henry V, to marry Charles VI’s daughter Catherine and assume the French throne at his death. However, in August 1422, Henry V died unexpectedly at the age of thirty-five, leaving an infant to reign as Henry VI in England. Less than two months later, Charles VI also died. In May of 1423, when Anne was eighteen, she was married to an English prince, John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, brother of King Henry V, who served as Regent for his nephew and commander of English forces in France (Backhouse 59).

Even before her marriage, Anne was known for distinctive dress. In 1421 she had a fur-lined green wool houppelande decorated with 300 small silver buckles. Because she was generous to others at court and charitable to the poor, she was not criticized for her extravagances (Scott 133). Her personal emblem — the yew tree, usually a symbol of mourning, suggests that like her brother Duke Philip she was ever mindful of her father’s death (Backhouse 58). Around the time of her marriage, Anne was portrayed in the prayer book known as the Bedford Hours (Fig. 1) wearing a sumptuous houppelande made of a silk velvet or brocade with a pattern of interlacing red branches, green leaves and blue pomegranates against a golden yellow ground. The Duke of Bedford wears a matching houppelande in his portrait (Fig. 2), a sign of parity between them (Scott 133). Like the Bedford Hours itself, which was begun in Paris some years earlier with the portraits of the couple inserted later (Backhouse 63), this luxurious Italian textile may have been a wedding gift from the Duke of Burgundy. Anne’s houppelande was made with long, ermine-lined bombard sleeves and a turned-down ermine collar. A second collar of white linen was a fashionable feature that continued from the previous decade. Just as extraordinary as her magnificent houppelande is Anne’s jewel-studded temple hairstyle and bourrelet (Fig. 1) remarkable for their richness as well as their size.

The Bedfords’ marriage proved to be a successful partnership as well as a happy one. The couple held court in Paris and Rouen and travelled frequently throughout northern France to shore up support for the young King Henry VI (Vaughan 9). Towards the end of the decade, the Anglo-Burgundian alliance began to fray. After Joan of Arc rallied the French around the Dauphin, who was crowned King Charles VII in 1429, it was increasingly difficult for Bedford to maintain English conquests in France, and the Duke of Burgundy began to consider making peace with the French (Vaughan 27). His sister Anne was the embodiment of the Anglo-Burgundian alliance; when she died early in the following decade, at the age of twenty-eight, the alliance would not long survive her.

During the nine years of her married life, Anne was the highest-ranked lady in France and as richly dressed as a Queen. Duke Philip accordingly commissioned a tomb for her fit for a queen. The tomb’s gisant or recumbent statue (Fig. 9) shows her in the formal ceremonial costume of a French queen, a surcôte over a côte-hardie; under her crown, her hair is in the style of the 1300s.

Menswear

The Fountain of Youth (Fig. 2), one of the frescoes at the Castello della Manta, reveals the underlayers of men’s dress during this decade; to the right of the fountain a young man, who has probably bathed in its waters, is being helped back into his clothes. We can see his linen drawers, including the ends of the drawstrings that hold them up at the waist, and his linen shirt (Fig. 1). These basic undergarments were worn by all men (Piponnier and Mane 87). The next garment is his doublet, closing with buttons down the front and at the cuffs of the long sleeves. This doublet has a two-tone floral pattern suggesting a linen or silk damask; the painter has clearly indicated a seam at the waistline and lines of stitching on the sleeves, including parallel lines at the sleeve cuffs, that would have perfected the doublet’s close fit. The doublet evolved in the previous century as a padded, quilted garment worn by knights to protect the upper body from the weight of plate armor, and it retained the prestige of its military origins (Van Buren and Wieck 2). Since it was quite short, the doublet was laced to a pair of long hose (Boucher 195).

Fig. 1 - Master of Manta (Italian, Early 15th century). Detail of The Fountain of Youth, 1411-16. Fresco. Saluzzo, Italy: Castello della Manta. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 2 - Master of Manta (Italian, Early 15th century). The Fountain of Youth, 1411-16. Fresco. Saluzzo, Italy: Castello della Manta. Source: Web Gallery of Art

In the foreground on the other side of the fountain, an elderly man is seated on the ground, removing his hose. The paired eyelets for the laces are visible at the top edges of the hose. The leather or braided fabric laces that connected doublet and hose were sometimes designed to catch the eye with contrasting colors and gilt metal tips. The young man standing behind Honor (Fig. 3) in the tapestry Honor Making a Chaplet of Roses (Fig. 1 above in Womenswear), wears a light-colored doublet and dark hose connected by means of red, gold-tipped laces. Various outer garments were worn over doublet and hose, such as the huque, a knee-length cape slit at each side that was favored by young men (Van Buren and Wieck 308). The other young man in the tapestry (Fig. 4), also wears a huque, and a red chaperon, a headdress made of draped fabric (Cavallo 150). Both men’s chaperons appear to be anchored by padded rolls analogous to women’s bourrelets, and like women’s headdresses they are decorated with pearl-studded brooches.

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (South Netherlandish). Detail of Honor Making a Chaplet of Roses, ca. 1420. Tapestry with wool warps and wefts; 236.2 x 274.3 cm (93 x 108 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 59.85. The Cloisters Collection, 1959. Source: MMA

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (South Netherlandish). Detail of Honor Making a Chaplet of Roses, ca. 1420. Tapestry with wool warps and wefts; 236.2 x 274.3 cm (93 x 108 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 59.85. The Cloisters Collection, 1959. Source: MMA

Fig. 5 - Assisted by Masaccio Masolino da Panicale (Italian, 1383-1447). Detail of two young men, The Healing of the Cripple, from Scenes from the Life of St. Peter, ca. 1424. Fresco. Florence, Italy: Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine. Source: Wikipedia

The most important outer garment for men during this decade remained the houppelande, which in Italy was called the pellanda or the cioppa (Herald 50). The two young Florentines who bear witness to a miracle performed by St. Peter in Masolino’s fresco The Healing of the Cripple (Fig. 13) wear knee-length versions in luxury fabrics. The one worn by the young man on the right is made of a fine wool or silk in a delicate shade of pink trimmed with blue, and it has sweeping bombard sleeves. His companion wears a cioppa made of green silk voided velvet. Masolino painted details of the floral pattern in gold, indicating that the textile was further decorated with gold brocading (Fig. 6). The cioppa is edged with fur and has sleeves in the poke style, cut like curved bags hanging from the shoulder and narrowing towards the wrist. The young man has hidden his hands in his sleeves as if they were a muff. His friend wears a chaperon of blue voided velvet, while his own is red, matching his red hose. Both wear soled hose that preclude the need for shoes. The presence of the young men, dressed in the height of fashion and showcasing the textiles that were the pride of Florentine industry, brought viewers closer to an event recounted in the New Testament.

During this decade we see more men dressed entirely in black, such as the donor kneeling before a saint in a Catalan altarpiece (Fig. 7), whose black houppelande and black chaperon, unfurled and draped over one shoulder, are relieved only by the white drawstring bag hung around his black belt. Over black hose, the donor in the Merode Altarpiece (Fig. 8), painted in Tournai in Flanders, wears a black houppelande with poke sleeves, a black chaperon de cou, which is like a capelet covering his neck and shoulders (Van Buren and Wieck 299), and he holds a black brimmed hat with a low crown. The man in the background standing by the city gate has been identified as a town messenger by the Metropolitan Museum; he holds a similar hat in a lighter color. All over Europe the taste for black was partly due to sumptuary laws such as the Statutes of Savoy that ranked red, obtained with the expensive kermes dye, as the most prestigious color, forbidden to all but the highest-ranking nobility (Piponnier and Mane 84). In several Italian city-states, non-nobles were not permitted to wear garments made of silk unless they were black. In Italian silk-weaving centers, these laws stimulated the production of black silks in intricate weaves such as velvets and brocades, for rich middle-class men who wanted to show their wealth within the bounds of the law (Piponnier and Mane 72).

Another factor was the influence of the new Duke of Burgundy. Philip the Good (1396-1467) became Duke upon the assassination of his father Jean the Fearless in September 1419 (Vaughan 2). Though black was customary as a sign of mourning, Philip prolonged his wearing of black to protest his father’s killing (Piponnier and Mane 73). On June 2, 1420, at the wedding of King Henry V of England to the French princess Catherine, at the church of St. John in Troyes in Burgundian-controlled eastern France, he stood out as the man in black in the colorful crowd (Backhouse 52-55). His practice of dressing head-to-toe in black was reinforced first by the death of his first wife, Michelle de Valois, in 1422, then by the death of his second wife, Bonne of Artois, who lived only a year after their marriage in 1424 (Beaulieu 18). Philip’s power and prestige, and the beauty of Italian silks in deep, lustrous black, furthered a fashion that transcended mourning customs and would endure well beyond this decade.

Rulers, princes and high-ranking aristocrats still wore traditional robes of state for the most formal occasions. For the ceremonies investing him as head of state in the various parts of his realm, even Philip the Good laid black aside for long tunics and a cape of red silk brocaded with gold leaves and lined in fur (Evans 44). The Duke of Bedford’s full-length houppelande with bombard sleeves, made of the same golden multi-colored brocade as his wife’s houppelande, was almost as formal. In his portrait in the Bedford Hours (Fig. 9), he kneels before St. George, patron saint of England, with his red chaperon unfurled over his right shoulder, as a mark of respect. We can see that underneath his showy, colorful outer garment, he wears a black doublet, and his hair is styled in the fashionable “bowl” cut. St. George is typically portrayed as a knight in armor, but here he also wears the ermine-lined blue cape and badge that denotes membership in the English order of chivalry, the Order of the Garter (Backhouse 59-60).

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (Italian). Textile with brocade, 14th century. Silk and linen brocade; 19.3 × 30.9 cm (7 5/8 × 12 3/16 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 12.55.1. Rogers Fund, 1912. Source: MMA

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown (Catalan). A Bishop Saint with a Donor (Saint Louis of Toulouse?), early 15th century. Tempera with raised and gilded gesso on wood; panel: 178 x 117.2 cm (70 1/16 x 46 1/8 in). Cleveland Museum of Art, 1927.197. Source: CMA

Fig. 8 - Workshop of Robert Campin (Netherlandish, c. 1375 – 1444). Detail of Annunciation Triptych (Mérode Altarpiece), ca. 1427–32. Oil on oak; 64.5 x 27.3 cm (25 3/8 x 10 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 56.70a–c. The Cloisters Collection, 1956. Source: MMA

Fig. 9 - Bedford Master (French). John, Duke of Bedford kneeling before St. George from The Bedford Hours, ca. 1430. Parchment, illumination; 26 x 18.5 cm. London: The British Library, Add. MS 18850, fol. 256v. Source: BL.UK

Fig. 10 - Bedford Master (French). Queen Clotilde presents the fleur-de-lys to King Clovis, detail of The Legend of the Fleur-de-lys, The Bedford Hours, ca. 1430. Parchment, illumination; 26 x 18.5 cm. London: British Library, Add. MS 18850, fol. 288v. Source: BL.UK

Fig. 11 - Master of Manta (Italian, Early 15th century). Braves and Heroines series: King Arthur and King Charlemagne, 1411-16. Fresco. Saluzzo, Italy: Castello della Manta. Source: Web Gallery of Art

The Bedford Hours also provides us with a good look at the plate armor of the 1420s (Fig. 16). The knight here represents the early medieval French King Clovis, who according to legend, had been given the fleur-de-lys as a heraldic symbol by his Queen, Clotilde, who was a Burgundian princess. The King is helped into his armor by two squires. His suit of armor is more flexible thanks to overlapping, asymmetrical curved pieces called pauldrons that buckled over the breastplate; below the pronounced waistline, the fauld or skirt of the suit was made with half a dozen overlapping horizontal pieces called lames. The lowest lame has a notch at the center to make it more comfortable to sit on horseback (Van Buren and Wieck 150). The squires wear colorful surcôtes over their own armor, like the kings in the Nine Worthies fresco at the Castello della Manta (Fig. 11). Suits of armor were necessarily custom-made, with the finest made in Milan during this decade (Van Buren and Wieck 150). There was no category of attire more aristocratic and masculine than armor, yet as the female Worthies at the Castello della Manta show, the idea of armored women was not inconceivable.

At the end of the decade this concept became reality. In 1429, a peasant girl from eastern France, Joan of Arc, claiming that her actions were directed by the voices of saints, dressed in men’s clothing and borrowed armor and led a French army to victory at Orléans, a city which had been long besieged by the English. This event turned the tide in the Hundred Years’ War in favor of the French. Joan’s cross-dressing, however, was considered so transgressive that it was used against her as proof of wickedness, when she was captured by the Burgundians and handed over to the English, to be tried as a heretic in the following decade (Crane 74-75).

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (French). Detail of Charles Spiefami and His Family Pray to Christ and St. John the Baptist, ca. 1424. Wall painting. Avignon: Church of Notre-Dame-des-Doms. Source: Pinterest

References:

- Backhouse, Janet. “A Reappraisal of The Bedford Hours.” The British Library Journal 7, no. 1 (1981): 47–69. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42554131

- Beaulieu, Michele, and Jeanne Bayle. Le costume en Bourgogne: de Philippe le Hardi a la mort de Charles le Temeraire. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1956. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/610379325.

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment. Expanded ed. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/979316852.

- Cavallo, Adolfo Salvatore. Medieval Tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/958958442.

- Crane, Susan. The Performance of Self: Ritual, Clothing, and Identity During the Hundred Years War. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/956785896.

- Evans, Joan. Dress in Medieval France. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1008513009.

- Herald, Jacqueline. Renaissance Dress in Italy 1400-1500. London: Bell & Hyman, 1981. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/492385048.

- Piponnier, Françoise, and Perrine Mane. Dress in the Middle Ages. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/943018667.

- Scott, Margaret. Fashion in the Middle Ages. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/777928739.

- Van Buren, Anne, and Roger S. Wieck. Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands, 1325-1515. New York: The Morgan Library & Museum, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/921010074.

- Vaughan, Richard. Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy. Woodbridge [UK]: Boydell Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/49942761.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1420-1429

Rulers:

- England

- King Henry V (1413-1422)

- King Henry VI (1422-1461)

- France

- King Charles VI (1380-1422)

- King Charles VII (1422-1461)

Europa 1400. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Events:

- 1420 – Treaty of Troyes, concluded May 21, disinherits the Dauphin Charles, and establishes that Henry V, King of England, will inherit the French throne at the death of King Charles VI. On June 2, as called for in the treaty, Henry V marries Charles VI’s daughter Catherine at the Church of St. John in Troyes. Duke Philip III of Burgundy attends the wedding dressed head-to-toe in black.

- 1420 – Beijing is officially designated the capital of the Ming Dynasty, during the same year that the Forbidden City, the seat of government, is completed.

- 1421 – Birth of future King Henry VI of England, son of Henry V and Catherine, at Windsor Castle.

- 1422 – Death of Henry V, at Château de Vincennes near Paris (August 31). His younger brother John, Duke of Bedford, is named Regent for Henry VI.

- 1422 – Death of Charles VI, King of France, in Paris (October 21).

- 1423 – Marriage of the Duke of Bedford to Anne of Burgundy, sister of Duke Philip III of Burgundy (May 13), at the Church of St. John in Troyes.

- 1427 – Saint Bernard of Siena preaches against Italian fashions for men, objecting to the exposure of underwear under too-skimpy doublets and too-tight hose, and to outer garments open at the sides such as the giornea or huque.

- 1428 – Itzcóatl becomes ruler of the Aztecs. He eventually begins the construction of Tenochtitlan.

- 1428 – Thomas Couette, a Carmelite monk, preaches against women’s hairstyles and headdresses throughout northern France, attracting large crowds.

- 1429 – The French, led by Joan of Arc, lift the siege of Orléans (May), an event that turns the tide in the Hundred Years’ War in favor of France. In July, at the Catheral of Reims, the Dauphin is crowned King Charles VII in Reims.

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 15th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.