OVERVIEW

The 1440s was a period centered around a more angular silhouette in fashion along with the end of popular fashions from the previous decade including the houppelande and other accessories. Regional fashions continued and fashion hubs were influenced by political events including the Hundred Years War.

The 1440s is an important time of transition. In northern Europe it was the last gasp of long houppelandes and horn-shaped headdresses. Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy consolidated his image as the “man in black,” and the women at his court lost their sway-backed, rounded appearance. The fashionable silhouette became sharper and more angular. The French regained some of their former influence over fashion as they recovered more of their territory from the English in the Hundred Years’ War, and as their economy improved. Italian fashion at first interpreted northern styles, then sought naturalism, simplicity, and a connection to the dress of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

Womenswear

Women’s fashion changed considerably during this decade, but the basic undergarment, the linen chemise, remained constant (Boucher 445). Glimpses of the chemise, underneath the next layer of clothing, the dress, can be seen in Rogier van der Weyden’s Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, worn by the figure of Mary Magdalene (Fig. 1). Artists commonly depicted some biblical figures in the dress of the present, to bring religious subjects closer to the viewer’s experience and intensify their emotional and spiritual appeal. Van der Weyden’s mournful Magdalene wears a fifteenth-century dress with a low, scooped neckline in front and back; he has shown us the seams that run down the center back and around the waistline where the skirt is joined to the bodice; the dress probably laces in the front. The smooth red fabric is a fine Flemish wool, lined in linen and laced firmly to achieve the fashionably tight fit.

Women’s dresses could be sewn with full-length sleeves or short ones, as in this example; the lower sleeves are made of a contrasting yellow fabric, possibly silk, and they are detachable, held on by metal-tipped laces (Frick 158). To her left, the figure of Maria Salome wears a dress of green wool under a heavy outer garment called the houppelande (Van Buren and Wieck 307). At the neckline, we again see a glimpse of the linen chemise under the front-lacing dress. The woolen houppelande is entirely lined in fur, as we can see from the turned-up skirt. It is belted at a high waistline, whereas Mary Magdalene’s belt is slung low around her hips. As her outer garment, Mary Magdalene wears a collared cape that has fallen down to her hips; it is in the same red wool as her dress, with a narrow trimming of gold cord along the edges and gold embroidery along the hem, where we see the upturned sole of her pointy right shoe. Such luxurious clothing, far from appearing inappropriate, shows respect for the importance of the scene (Frick 86). The women’s headdresses, however, are simple and conservative in style. Mary Magdalene’s is a linen veil draped around her head and pinned in place; Mary Salome’s veil is crimped around the edges.

In Italy, these fashions that emanated from France, Flanders and Burgundy were still influential in the 1440s, as seen in The Portrait of a Woman with a Man at a Casement by the Florentine painter Fra Filippo Lippi (Fig. 2). The woman’s chemise is seen at the neckline as the faintest wisp of transparent linen. In Italy, the dress was called variously the cotta, gonella, or gamurra, depending on the region and the fabric it was made of (Frick 162, Herald 47-50). Only the left sleeve of this dress is visible. Fra Filippo Lippi has taken the utmost care to render an Italian textile of the utmost luxury: a polychromatic voided and brocaded velvet similar to figure 3. The painted textile has scattered alluciolato weft loops of gold, like points of light in the dark velvet pile (Monnas 301). The sleeve of the dress is constructed in two parts; the upper sleeve is full and pleated into the seam just above the elbow, where it joins the fitted lower sleeve. Since women’s clothing, especially their attire for special occasions, was made by male tailors (Frick 81-82), not surprisingly men’s sleeves were constructed in a similar manner.

Fig. 1 - Roger van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1400-1464). Detail of Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, 1445-50. Oil on oak; 200 x 223cm. Antwerp: Royal Museum of Fine Arts, 393-395. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 2 - Fra Filippo Lippi. Portrait of a Woman with a Man at a Casement, ca. 1440. Tempera on wood; 64.1 x 41.9 cm (25 1/4 x 16 1/2 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 89.15.19. Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1889. Source: The Met

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (Italian). Textile fragment, 1420s. Silk; voided velvet; 63.5 x 52.1 cm. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 46.156.115. Fletcher Fund, 1946. Source: The Met

The woman’s next layer of clothing is a red wool houppelande, which in Italy was known as the cioppa or pellanda (Herald 50). This example has the characteristic “pipe pleats” (Van Buren and Wieck 174), that were probably steamed into shape and stitched in place. It is trimmed, or perhaps entirely lined, in a white fur with pale spots. Although the Metropolitan Museum describes the woman as “dressed luxuriously alla francese,” the houppelande sleeves, which are slit from the shoulder to a wide band at the wrist, revealing the sleeves of the dress underneath, are a particularly Florentine style, called maniche a gozzi (Frick 192-194). The band at the lower edge of the left houppelande sleeve has been embroidered with a motto, “Lealtà,” (Loyalty) in metallic thread and tiny white pearls. In 1439, not long before the portrait is thought to have been completed, a sumptuary law was passed in Florence confining embroidered decoration to sleeves.

Embroidered emblems and mottos remained very fashionable in this decade; often they are difficult to interpret (Frick 197), but this motto lends support to the notion that the portrait celebrates an engagement or marriage and that the woman is wearing her wedding finery (Frick 128-131), which includes a pearl necklace, two pearl and gemstone brooches, and several rings. Although the portrait is half-length, we can surmise that the houppelande is excessively long and trails on the ground, given her gesture of lifting and holding the excess length in front of her body, which is characteristic of the 1430s and early 1440s. Voluminous, heavy garments were thought to lend dignity, causing the wearer to move slowly, as in a wedding procession (Frick 91-93). The woman’s headdress is no less luxurious than her garments. Her blond hair has been gathered into one or two gold-embroidered caps edged with pearls, and surmounted by a bourrelet, a padded roll covered with fabric that in Italy was called a ghirlanda (Herald 50). This one is made of red silk, with sections cut in the decorative technique known as dagging in northern Europe and frappature in Italy (Herald 56), and heavily embroidered with gold thread, gold beads and pearls; it has two hanging lappets (the longer one can be seen hanging past her right shoulder down to her waist), also heavily embroidered with these precious materials.

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (Netherlandish). Courtiers in a Rose Garden: A Lady and Two Gentlemen, 1440-50. Wool warp; wool, silk, metallic weft yarns; 288.9 x 325.1 cm (9 ft 5 3/4 x 10 ft 8 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 09.137.2. Rogers Fund, 1909. Source: The Met

A Flemish tapestry (Fig. 4), one of a group titled Courtiers in a Rose Garden, provides a frontal view of this type of headdress. It begins with a horn-shaped hairstyle called “a pair of temples,” two cones of coiled hair held in place at the temples with hairnets and pins (Van Buren and Wieck 317-318). A flat cap typically covered the top of the head, in between the cones. The cap and the hairnets, which were called crispins (Van Buren and Wieck 150), could be elaborately decorated, as in the tapestry, where they look encrusted with pearls and other gemstones. When placed on top, the circular bourrelet settles into the horned shape and is held in place by pins. The example represented in the tapestry appears to be made of silk damask. The horn-shaped hairstyle topped with a bourrelet had evolved since the early years of the century; it reached its maximum size in the 1420s, and acquired hanging lappets and draperies, as seen in the tapestry, in the 1430s.

An alternative to the bourrelet was the huves headdress of linen veils, suspended on wires driven into the cones of hair (Van Buren and Wieck 308). An example made with layered veils of very fine transparent linen can be seen in figure 5. By the 1440s, the “pair of temples” hairstyle upon which both headdresses rested was nearing the end of its lifecycle (Van Buren and Wieck 177).

Another significant change is reflected in the tapestry. The voluminous houppelande was giving way to the close-fitting dress, either worn alone or layered over another. The green dress in the tapestry has the new neckline in a deep-V, emphasized with contrasting trimming and filled in with a small piece of fabric called a partlet (Van Buren and Wieck 168). The trimming reappears as cuffs at the ends of the narrow sleeves and along the hemline of the dress. The excess length elongates the silhouette and ensures slow and stately deportment.

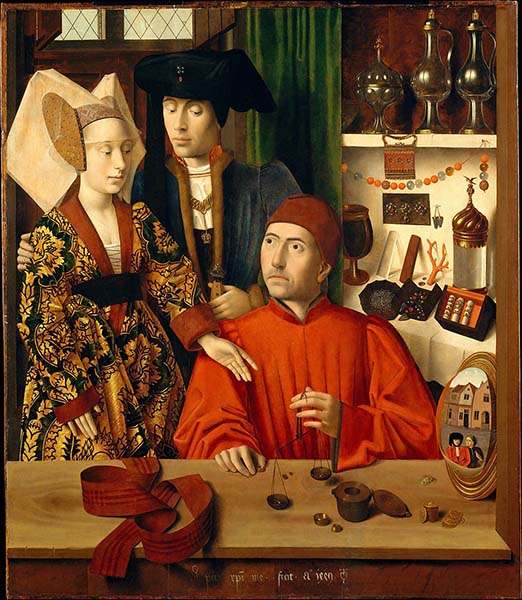

Fig. 5 - Petrus Christus (Netherlandish, 1410-1475). A Goldsmith in his Shop, 1449. Oil on oak panel; 100.1 x 85.8 cm (39 3/8 x 33 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.1.110. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975. Source: The Met

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (Netherlandish). Courtiers in a Rose Garden: Two Ladies and Two Gentlemen, 1440-50. Wool warp; wool, silk, metallic weft yarns; 314.3 x 247.7 cm (123 3/4 x 97 1/2in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 09.137.1. Rogers Fund, 1909. Source: The Met

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. Ladies on a Balcony, 1448. Stone. Bourges: Upper room fireplace, Palais Jacques-Coeur. Source: TripAdvisor

The young woman in the Portrait of a Goldsmith (Fig. 5) wears a similar dress, though hers is made of a sumptuous gold-brocaded voided velvet with straight loose-fitting sleeves. She has taken up the excess length of the dress and tucked it up under her right arm. In this transitional decade, both she and the woman in the tapestry are dressed in transitional style. Their dresses are new but their headdresses are not.

However, in another tapestry in the Courtiers in a Rose Garden group (Fig. 6) the women wear dresses in the new style with headdresses based upon the turret, a single mound of hair covered with a hairnet or cap, rather than “a pair of temples” (Van Buren and Wieck 178). In the case of the woman in the lower register of the tapestry, embroidered hairnets still cover her hair at the sides, and a bourrelet with hanging lappets and a panel of drapery is still placed on top, but it has been folded into a tight curve at the center front and it is smaller and much narrower. The black semi-circle at her hairline is a fabric-covered wire that extends into the turret to help keep it in place (Van Buren and Wieck 178). The woman in the upper register of the tapestry is dressed in a more advanced style. Her dress has a very low V-neckline and a long train, folded back to one side. Her turret is a cylindrical red cap that completely encapsulates her hair, and over it is an M-shaped structure of wires from which layers of fine linen are suspended. This new variation on the huves, which looks like “a ship in full sail” (Van Buren and Wieck 150), is called the banner headdress. While these tapestries are made up of pieces joined together with areas of later reweaving, the areas representing the figures are mostly original (Cavallo 174). However eccentric the fashions appear, there is no reason to think their representation is particularly exaggerated. More examples of the banner and other headdresses based upon the turret can be seen in illuminated manuscripts (Van Buren and Wieck 172-179) and in the sculptures decorating the merchant Jacques Coeur’s house in Bourges, completed circa 1448 (Fig. 7).

By the end of the 1440s, women’s fashion in northern Europe was quite different. The fashionable woman no longer assumed a swaying posture with her abdomen thrust forward, balancing the weight of a heavy houppelande belted at a high waistline; she stood upright in a fitted dress with a revealing neckline and a wide belt at the natural waist. Her sleeves were no longer voluminous bags of fabric, but straight and narrow. Her headdress was no longer horn-shaped, but conical, and increasingly tall.

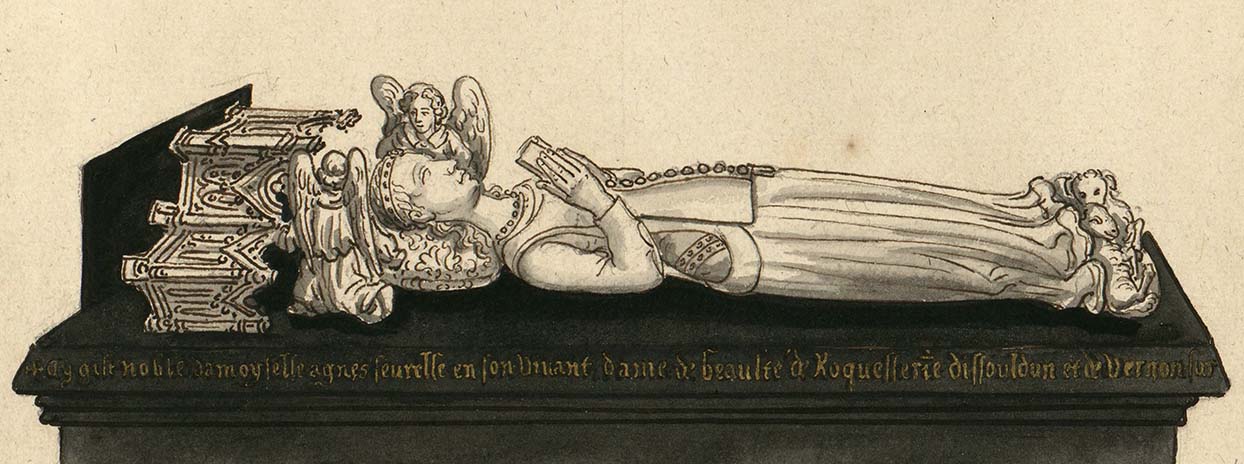

Some historians attribute these changes to the influence of Agnès Sorel, the mistress of King Charles VII of France. Sorel was the King’s mistress from 1444 until her death early in 1450, at the age of twenty-eight. She was the first royal mistress to be officially recognized and held a powerful position at court (Wellman 25-57). She was criticized for having trains on her dresses that were one-third longer than those of princesses (Evans 45) and for wearing very low-cut necklines (Scott 145). It is possible that rather than invent new fashions she simply took trends to their extreme. She was remembered as the embodiment of the ideal beauty of the era, who had extremely pale skin, plucked eyebrows and forehead, and delicate features. Her alabaster tomb effigy shows her dressed in the traditional fourteenth-century côte-hardie and sideless surcote that was worn for the most formal court ceremonies (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 - Louis Boudan (active 1695-1715). Detail from Tomb of Agnès Sorel at the Collégiale de Saint Ours, Loches, 1695 (tomb ca. 1450-54). Paper; 36.1 x 23.6 cm. Paris: Bibliothéque Nationale de France, Gaignières, 3870; Reserve PE-2-FOL. Source: Gallica

Meanwhile in Florence, where low V-necklines, considered to be French, had been banned since 1439 (Scott 145), there were signs that women’s fashion was heading in a different direction. In Scheggia’s Portrait of a Lady (Fig. 9), the lady has golden skin, spots of color on her cheeks, and dark pink lips. Her hair has been brushed into loose swirls around her ears and held in place with a strip of linen and a black silk cord. Such a hairstyle, like the concept of a profile portrait, was inspired by ancient sculptures and coins (Sorabella). Though made of expensive silks with intricate patterns, her garments too are simple in form: a dress (gamurra) and a giornea, a sideless cape (Herald 48). Her necklace is a double row of coral beads and pearls, and her simple hairstyle is surmounted by a matching brooch. Clearly, simplicity does not preclude luxury and refinement. In the following decade, Italian fashion for women would take further steps in this direction, which would bring it closer to the dress of classical antiquity.

Fig. 9 - Giovanni di Ser Giovanni Guidi (Italian, 1406-1486). Portrait of a Lady, ca. 1460. Tempera and gold on panel, transferred to canvas; 44.1 x 36.4 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 34. John G. Johnson Collection, 1917. Source: PMA

Fashion Icon: Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy (1396-1467)

Fig. 1 - After Rogier van der Weyden. Portrait of Philip the Good, 1445. Oil on wood; 31.5 x 22.5 cm. Dijon: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 3782. Source: Joconde

Fig. 2 - Jean Peutin (Flemish, 15th century). Golden Fleece Chain, 15th century. Gold. Source: Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi

Duke Philip the Good of Burgundy had influenced fashion since his accession in 1419, following the assassination of his father, Jean the Fearless, at the hands of the French. To protest his father’s killing and express his resolve to hold the French accountable, Philip wore mourning black long after the customary period of mourning had expired (Piponnier and Mane 73). For the next two decades, he was the man in black around whom a competitive, luxury-loving court revolved. Due to his status as the richest man and greatest patron of the arts in northern Europe (Vaughan 150), inevitably he influenced other men to dress in black, such as Giovanni Nicolao Arnolfini, believed to be the man in van Eyck’s 1434 Arnolfini Portrait, now at the National Gallery in London (see 1430-1439 overview). Even after he had made peace with France at the Treaty of Arras in 1435, Philip continued his practice of dressing head-to-toe in black, no doubt because it was integral to the public image he had established. He may also have discovered that black clothing makes a powerful statement and is an ideal background for the display of jewelry, such as the collar and pendant of the Golden Fleece, the chivalric order he had founded in 1430 (Vaughan 160-161). Since he was the greatest consumer of Italian silks north of the Alps, Philip’s black doublets, houppelandes and chaperons were anything but plain. From 1444 to 1446 he is estimated to have spent 2% of Burgundy’s main tax income with a single Italian supplier of silk and cloth-of-gold, Giovanni di Arrigo Arnolfini, cousin of Giovanni Nicolao (Campbell). Though a significant portion of these purchases must have been for furnishing, gifts, and supplies of livery to the members of the court, when we interpret portraits of the Duke we can assume he is dressed in Italian silk velvets and the finest Flemish wools. The court chronicler Geoges Chastellain wrote that he “dressed smartly but in rich array, and was always changing his clothes…” (quoted by Vaughan 127).

The portraits of Philip the Good made during this decade defined his image for posterity. The most important portrait, a half-length panel painting after Rogier van der Weyden dated circa 1445 (Fig. 1), shows him dressed in a black doublet, with the laces fashionably pulled apart to reveal his white linen shirt; hanging from one of the laces is a gold pendant in the form of a cross, with a ruby and four pearls. His outer garment is a black houppelande trimmed with brown fur at the neckline and sleeves. The Duke wears a black chaperon that was made by covering a padded roll with fabric, as in women’s bourrelets, and draping fabric around it, hence the name for this type of men’s headdress, chaperon à bourrelet (Van Buren and Wieck 297). Two layers of cloth project from the back of the chaperon, and the long trailing end, the cornet (Van Buren and Wieck 300) hangs down past his right shoulder. A gold and gemstone brooch with a large hanging pearl and four smaller pearls is pinned on the chaperon. The unrelieved black ensemble focuses attention on the jewelry, especially the collar and pendant of the Golden Fleece (Fig. 2). The links of the collar are interlaced Bs for Burgundy, alternating with the Duke’s personal badge, the flaming flint (Fig. 3).

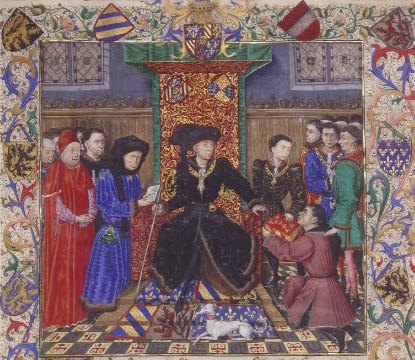

Other portraits of Philip the Good illustrate the changes in men’s fashion during this decade, even as they reinforce his image as the man in black. In an illuminated manuscript dedicated to the Duke, Le Roman de Girart de Roussillon (Fig. 4), he is shown full-length, sitting on a throne in front of a red cloth-of-honor embroidered in gold, wearing a black doublet with the laces pulled apart to reveal the shirt, again with a gold pendant hanging from one of the laces at his throat. Over his black doublet and hose, he wears a long houppelande of a boldly patterned voided velvet, lined with brown fur. The straight sleeves of the houppelande rise up at the shoulders and are possibly supported by small cushions, called maheutres (Van Buren and Wieck 174). Philip’s trim waistline is emphasized with a narrow black and gold belt, from which hangs a small black and gold gipser, a bag hung on a belt (Van Buren and Wieck 304). In this portrait too he wears a black chaperon, with the cornet hanging down on the right side. His shoes are extremely pointy poulaines (Van Buren and Wieck 314). The Duke is surrounded by courtiers, with his son and heir Charles, also dressed in black, to his left. The scene is filled with references to his identity; the heraldic motifs in the coats-of-arms embroidered on the cloth-of-honor are repeated on the carpet under his feet; the floor tiles alternate letters spelling out his mottos “mon yoie” (my joy) and “alture narey” (no other will I have), with his badge of the flaming flint (Monnas 240).

Fig. 3 - Jean Peutin (Flemish, 15th century). Detail of Golden Fleece Chain, 15th century. Gold. Source: Archivio Digitale Boncompagni Ludovisi

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Detail of Roman de Girart de Roussillon, ca. 1448. Manuscript. Vienna: Östereichische Nationalbibliothek, MS 2549, folio 6r. Source: ONB

Fig. 5 - Roger van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1400-1464). Detail from Simon Nockart Presents the Book to Philip the Good, 1448. Manuscript. Brussels: Royal Library of Belgium, KBR MS 9242, fol. 1. Source: KBR

In the contemporary manuscript Chroniques de Hainaut, the frontispiece dedication page was painted by Rogier van der Weyden (Fig. 5). The Duke’s attire is almost identical: black doublet revealing the white shirt, black hose, black voided velvet houppelande trimmed or lined in brown fur, black chaperon, gold pendant at the throat and the collar and pendant of the Golden Fleece. Some details are slightly different or new. He holds a hammer, a symbol of authority, in his right hand. (Van Buren and Wieck 174). The cornet of the chaperon is drawn under the chin to fasten on the opposite side, and in this portrait he is clearly wearing wooden-soled pattens, which in this decade men no longer remove indoors (Van Buren and Wieck 164). The houppelande is slit up the sides but has no discernible opening at the front below the waist. However, the only appreciable difference is in the length of the houppelande. It is above the knee, and thus could also be called an haincelin (Van Buren and Wieck 307). This change to Philip’s established personal uniform shows that it was adaptable to changing fashions. In the late 1440s, long houppelandes were decidedly old-fashioned. In this scene they are worn by the older men to the Duke’s right, including the seventy-one-year-old Chancellor Nicholas Rolin, in blue (Van Buren and Wieck 174). Philip’s short, sharply tailored haincelin exemplifies the angular lines of the new fashion for men. This portrait too demonstrates that the man in black stands out in a crowd, that an all-black ensemble shows the fashionable silhouette to best advantage, and that black is beautiful, elegant and glamorous. As the first “man in black” to fully exploit its power, Philip the Good deserves a special place in fashion history.

Menswear

Fig. 1 - Petrus Christus (Netherlandish, 1410-1475). Portrait of Edward Grimston, 1446. Oil on panel; 33.6 x 24.7 cm (13.2 x 9.7 in). London: National Gallery of Art, L3. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. Detail of Roman de Girart de Roussillon, ca. 1448. Manuscript. Vienna: Östereichische Nationalbibliothek, MS 2549, folio 9v. Source: ONB

In 1446 an English diplomat named Edward Grimston (Fig. 1) arrived in Flanders to negotiate a trade agreement with the Duke of Burgundy on behalf of the English King, Henry VI. In Bruges, he ordered some new clothes from a local tailor and wore them to sit for his portrait by Petrus Christus (Van Buren and Wieck 168). It is extremely rare for the costume in a fifteenth-century painting to be so thoroughly documented. The portrait (Fig. 1) shows his first layer of clothing, a linen shirt, the basic undergarment worn by all men along with a pair of linen drawers (Piponnier and Mane 87). In this decade it became fashionable to reveal the shirt by leaving the next garment, the doublet, open in the front. Grimston’s doublet, a brilliant orange-red in color, is probably made of silk. It has paired red laces that have been pulled apart. The sleeves of the doublet are made in two parts, with the full upper part gathered and joined to the fitted lower part. This style was thought to have originated in northern Italy, and was called the Lombard sleeve (Van Buren and Wieck 311). Grimston’s bright green outer garment is probably a short houppelande, also called an haincelin, with slit sleeves. It is in these outer garments, and the style of their sleeves in particular, that the changes in men’s fashion were seen.

Since this portrait is half-length, it is impossible to say for sure what the rest of the garment looked like, but an illumination in the manuscript Le Roman de Girart de Roussillon (Fig. 2), completed a few years later, offers a clue. In this wedding scene, where the bridegroom wears an elaborate long houppelande with dagged sleeves as a formal ceremonial costume to match the bride’s sideless surcote, one of the guests is dressed very similarly to Edward Grimston, in a red doublet and a green haincelin with slit sleeves. Given the same color scheme of complementary red and green, it is likely that Grimston too wears red hose to match his doublet.

The hose, separate leggings that were laced to the hem of the doublet (Van Buren and Wieck 307), would probably have been custom-made for Grimston by the same tailor who made his other garments. Most pairs of hose were made of wool; a wool jersey called perpignan was particularly favored (Frick 167). Since he wears no shoes, the wedding guest’s hose must have attached leather soles, which was not unusual. In Florence, soled hose was sold ready-made (Frick 45).

The man’s haincelin is heavier than Grimston’s because it is trimmed or lined in fur, and he wears a fur-lined hat with an upturned brim called a barret (Van Buren and Wieck 295), whereas Grimston wears a black chaperon à bourrelet in the style of the Duke of Burgundy, only with the cornet hanging over his left shoulder. Both men wear gold necklaces, though Grimston’s is half-hidden under his haincelin. The interlacing “S” links in the silver chain in his right hand are symbols of the dynastic house of Lancaster, to which Henry VI belonged (X). The coats of arms seen in the background are Grimston’s own. The portrait attests to his status and English nationality, along with his very diplomatic adherence to the latest fashions in the Duke of Burgundy’s realm.

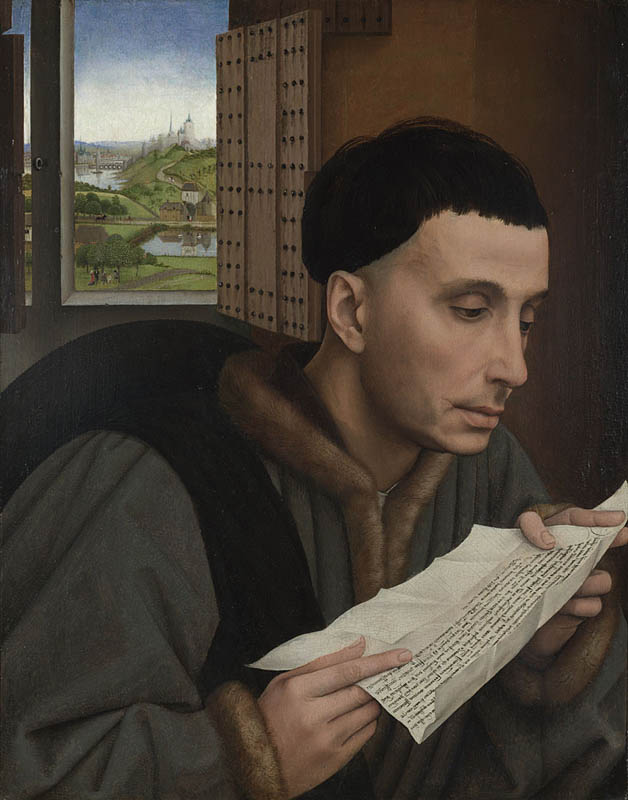

Most men in the 1440s wear variations of the haincelin. Individual style was expressed through the choice of fabric, whether plain or with a woven or embroidered pattern, the choice of color in relation to the doublet and hose, the type of sleeve and the accessories. The young man in A Man Reading (Fig. 3) is very quietly dressed, in a black doublet and a grey haincelin, with a black chaperon slung over his shoulder in a manner very characteristic of this decade (Van Buren and Wieck 174). The portrait shows us an excellent look at the bowl haircut that most men in northern Europe sported (Van Buren and Wieck 311). Although the painting is dated to the end of the decade, the full sleeves are conservative in style, and he wears no jewelry. Despite the apparent austerity of his dress, the haincelin has the soft, velvety look of the finest Flemish wool, and it might be completely lined in fur.

By contrast, a young man seen in another painting from the work-shop of Rogier van der Weyden, dated to the beginning of the decade, The Exhumation of St. Hubert (Fig. 4) is splendidly dressed in a gold-brocaded voided velvet haincelin over an apple green doublet and wine-colored hose. When interpreting such lavish textiles and color schemes in paintings, we must consider the possibility that the extremely expensive luxury fabric was merely depicted by the painter based on a drawing or sample, rather than actually used to make the garment (as in figure 5 in womenswear above, where the scale of the pattern on the young woman’s dress changes from the sleeves to the skirt), and that artists might have cared more about color harmony in their compositions than they cared about depicting dress accurately.

Nevertheless, there are many sources that show men very colorfully dressed, such as figure 5 in the Fashion Icon section above). In figure 5, we can appreciate details about the construction of the haincelin that appear to be accurately observed, such as the rounded “pipe pleats,” stitched in place on the interior, that converge at the natural waistline and widen to the hemline, the V-shaped back neckline of the garment, and the high slit at the side. The sleeves of this haincelin are of the “bag” type, but with a deep slit that freed the arm entirely, like the Florentine maniche a gozzi seen in figure 2.

Fig. 3 - Roger van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1400-1464). A Man Reading, ca. 1450. Oil on oak; 45 x 35 cm. London: National Gallery of Art, NG6394. Source: NGA

Fig. 4 - Roger van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1400-1464). Detail from The Exhumation of Saint Hubert, late 1430s. Oil with egg tempera on oak; 88.2 x 81.2 cm. London: National Gallery of Art, NG783. Source: NGA

Fig. 5 - Petrus Christus (Netherlandish, 1410-1475). A Goldsmith in his Shop, 1449. Oil on oak panel; 100.1 x 85.8 cm (39 3/8 x 33 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.1.110. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975. Source: The Met

Fig. 6 - Jean Fouquet (French, c. 1420-1481). Portrait of Charles VII, 1445-50. Oil on oak; 85.7 x 70.6 cm. Paris: Louvre, INV 9106. Source: Louvre

Another aspect of the haincelin’s construction that varied was whether it was open down the front or closed, in which case it would fasten at the back or side. In Portrait of A Goldsmith (Fig. 5) we see examples of both. The goldsmith’s garment might be a full-length houppelande rather than an haincelin, given its conservative closed construction. On the other hand the King of France, Charles VII (Fig. 6), was portrayed wearing a similar garment of red velvet, probably lined in fur and with maheutres supporting the sleeves at the shoulders, a very up-to-date feature in the late 1440s. The young man visiting the goldsmith’s shop, however, wears an haincelin of blue silk velvet edged with fur that is open down to his waist, allowing us to see that his doublet is made of two contrasting materials, a shiny red silk for the upper part, and black for the lower, central piece that is like a woman’s partlet. This touch of black is echoed in his elegantly draped black silk chaperon, while the ruby hanging from the pearl brooch on the chaperon echoes the reds that are present throughout the painting. In general, in northern Europe, men’s haincelins got shorter and more streamlined as the decade advanced, with front openings, straighter sleeves, cinched waists and slits at the sides, as seen in the Courtiers in a Rose Garden tapestries (Figs. 4 & 6 in womenswear) and among the men gathered around Philip the Good, all knights of the Order of the Golden Fleece, in the Chronique de Hainaut (Fig. 4 in the fashion icon section).

In Italy, the same trends were seen but with some differences, as in women’s fashion, that signalled that Italian fashion would pursue an increasingly divergent path. The young Sienese man seen in a fresco by Domenico di Bartolo (Fig. 7) wears a voided velvet short houppelande that would be called a cioppa, the Italian name for houppelande. It has the fur lining, V-shaped back neckline, and pipe pleats cinched at the waist that were also seen in northern Europe. The sleeves, however, are neither “bags” nor straight, but flaring, pleated panels hanging from the shoulders, as long as the garment itself. The left sleeve has been turned up onto the shoulder, anchored either by the weight of the heavy fur-lined velvet, or held in place with pins. This is an alla togata sleeve, in the style of a Roman toga (Herald 57). Admittedly this cioppa does not resemble the toga at all, but the drapery of the sleeve on the shoulder is an allusion to it.

Fig. 7 - Domenico di Bartolo (Sienese, 1400-1445). Detail of Pope Celestinus III Grants Privilege of Independence to the Spedale, 1442. Fresco. Siena: Pellegrinaio, Spedale di Santa Maria della Scala. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 8 - Giovanni da Oriolo (Italian, active 1439, died by 1474). Portrait of Leonello d’Este, ca. 1447. Tempera on wood; 57.6 x 39.5 cm. London: National Gallery, NG770. Source: NGA

Under the cioppa the man wears a red doublet, which in Italy was called the farsetto (Frick 160) and brightly parti-colored hose, called calze (Herald 211). The practice of dividing up the parts of a garment or accessory and using contrasting colors for each part derived from medieval heraldry (Piponnier and Mane 133). Although it was no longer seen so much in northern Europe, it persisted in Italy, where a parti-colored item would be called adogato (Herald 209). Italian men rarely wore shoes, preferring soled hose to pointy poulaines or pattens (Herald 227). Another notable difference about the young man’s appearance is that underneath his black hat with upturned brim, his wavy red hair is shoulder length. A pet ferret, its long tail curling around his neck, might be considered another accessory; such small animals were symbols of fertility and had the practical purpose of drawing away fleas; their pelts (zibellini) often mounted with jewels, were women’s accessories (Sherrill).

Italy was the source for the patterned voided velvets seen in northern Renaissance paintings, yet among Italians there was ambivalence about consuming these luxury goods themselves (Frick 188). In the city of Brescia in Lombardy in 1439, weavers were blamed for dressing their wives in red velvet and “bringing misfortune on the city” (Scott 136). Red, especially the bright orange-red obtained with kermes dye, was the most expensive and prestigious color, and velvet, since it has one or more extra warps, the most expensive weave. Morello di grana, the most expensive black dye, was only half as costly as kermes, and thus not particularly prestigious (Frick 175). In Italy there were fewer “men in black.” Black clothing retained its traditional association with mourning, rather than with elegance (Scott 144).

Leonello d’Este, who inherited his father Niccolò’s rule over Ferrara in 1441 despite his illegitimate birth, wears both red and black in his portrait by Giovanni da Oriolo (Fig. 8). Leonello was one of the era’s most sophisticated patrons of the arts. Under the guidance of the humanist Guarino Veronese, he gathered at his court not only Pisanello but also Leon Battista Alberti, Jacopo Bellini, Piero della Francesca, and Rogier van der Weyden (Beamish). The profile portrait displays a tendency towards naturalism, seen in the longer hair, and towards simplicity. His shirt is seen as a sliver of white atop the high neckline of his doublet, which has sleeves in the Lombard style. His outer garment is the giornea, a sideless cape, that appears to be of deepest black velvet edged with gold trimming. A contemporary, Angelo Camillo Decembrio, has left this description:

“His style of dress – and one’s dress can be a source of respect and good will among gentlemen – was noteworthy for its tastefulness. He was not concerned with opulence and ostentation, as some other princes are. But – now you will find this remarkable – he thought out his wardrobe in such a way as to choose the colour of his garments according to the day of the month, and the position of the stars and the planets.” (quoted in Herald, 100)

The portrait contains an interesting detail. The doublet sleeves have a row of eyelets intended for lacing on the shoulder pieces of a suit of armor. This recalls the origins of the doublet in the previous century as a “doubled,” padded garment that would protect a knight’s body from the weight of plate armor (Van Buren and Wieck 2). By choosing to wear a military doublet, ready to be laced into armor, Leonello d’Este was making an understated show of strength.

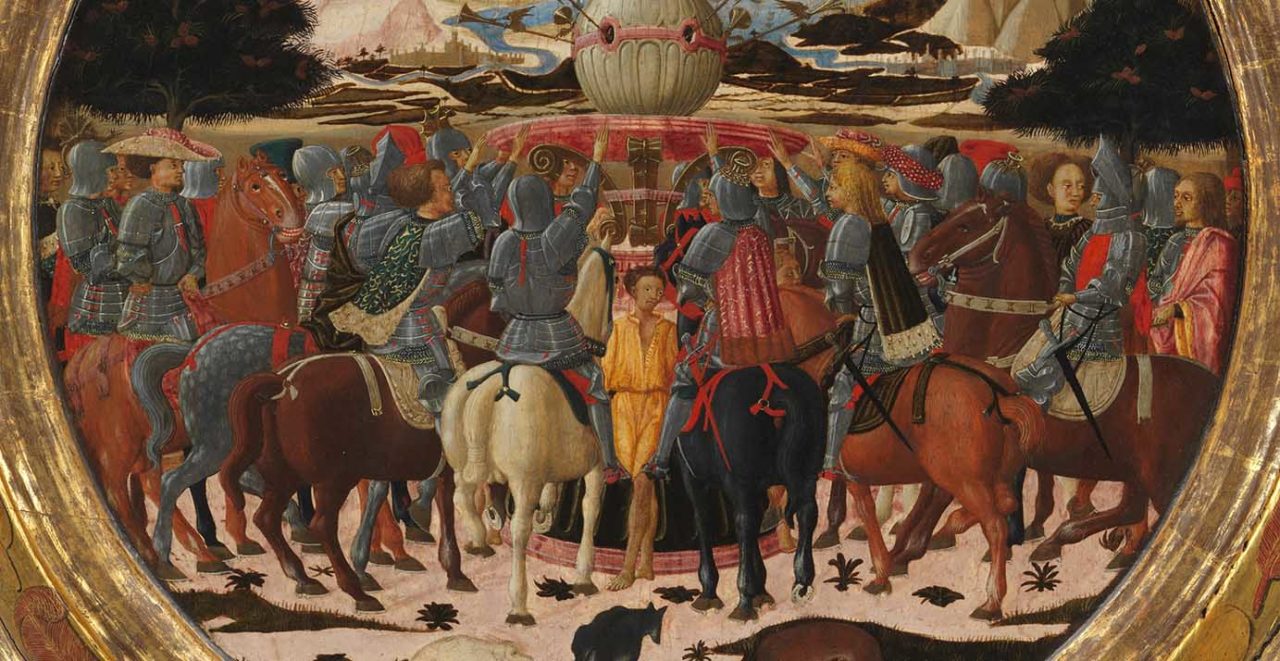

Fig. 9 - Giovanni di Ser Giovanni Guidi (Italian, 1406-1486). Detail The Triumph of Fame, ca. 1449. Tempera, silver, and gold on wood; 62.5 cm (24 5/8 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995.7. Source: The Met

The armor of the mid-fifteenth century is on full display in The Triumph of Fame (Fig. 9), the painted birth tray made in Florence in 1449 to celebrate the birth of Lorenzo de Medici, the future “Lorenzo the Magnificent.” Under the armor that encases the knights’ bodies almost entirely, there are glimpses of red doublets and hose, and the red straps that tie the various pieces of the armor together. The work of armorers and tailors continued to be closely related. Armorers necessarily conceived of the body as an assemblage of connected parts, or segments, and tailors mirrored this segmentation in the cut and fit of men’s garments (Newton 2-3). Over their breastplates, some knights are shown wearing short flowing capes. One figure at the far right has a large piece of drapery thrown over his suit of armor. The paradox of men’s fashion in mid-fifteenth-century Italy is that the basic garments of men’s dress, doublet and hose, were getting more and more fitted, just as armor was more intricately made, yet the Italian ruling elite, steeped in humanist culture, was more and more attracted to the opposite of tailoring – drapery, the costume of antiquity. The tension between these two impulses would play out in subsequent decades.

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Roger van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1400-1464). Detail from Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, 1445-50. Oil on oak; 200 x 223 cm. Antwerp: Royal Museum of Fine Arts, 393-395. Source: Wikimedia

Young children during this decade continued to be dressed in loose-fitting tunics of linen and wool, layered one over the other according to the season. As they grew older, children of the middle and upper classes were dressed in simpler versions of adults’ garments. The boys shown taking the sacrament of confirmation in Rogier van der Weyden’s Seven Sacraments Altarpiece (Fig. 1) wear conservatively long houppelandes with baggy sleeves, but they have fashionable pipe pleats, belts at the natural waistline, and pointy shoes. The youngest boy wears a narrowly cut, very long outer garment that laces down the front. They have bowl haircuts and wear their chaperons draped on their shoulders, not only because it was fashionable but because it would be disrespectful to keep them on inside a church. The youngest boy carries his small red chaperon, decorated with dagging, in his right hand. The small figure half-hidden behind them may be their widowed mother since she wears a black veil. Portraits of the Duke of Burgundy that include his son Charles (Figs. 2 & 3) show him every bit as richly and fashionably dressed as his father.

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. Detail of Roman de Girart de Roussillon, ca. 1448. Manuscript. Vienna: Östereichische Nationalbibliothek, MS 2549, folio 6r. Source: ONB

Fig. 3 - Roger van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1400-1464). Detail from Simon Nockart Presents the Book to Philip the Good, 1448. Manuscript. Brussels: Royal Library of Belgium, KBR MS 9242, fol. 1. Source: KBR

References:

- “1400–1500 in European fashion” Wikipedia. Accessed September 16, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1400%E2%80%931500_in_European_fashion

- Beamish, Gordon Marshall. “Lionello d’Este, 13th Marchese of Ferrara” in “Este Family,” Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, 2003. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:3206/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T026743

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume in the West. New York: Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/824293869

- Campbell, Loren. The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Schools. National Gallery Catalogues, London, 1998. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/464192859

- Cavallo, Medieval Tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/464222703

- Evans, Joan. Dress in Medieval France. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/939659457

- Frick, Carole Collier. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes and Fine Clothing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62133195

- Grollemond, Larisa. “Art Stories: Arts of Luxury for the Renaissance Elite.” Getty Museum, August 27, 2018. http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/arts-of-luxury-for-the-renaissance-elite/

- Herald, Jacqueline. Renaissance Dress in Italy, 1400-1500. London: Bell & Hyman, 1981. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/492385048

- Monnas, Lisa. Merchants, Princes and Painters: Silk Fabrics in Italian and Northern Paintings 1300-1550. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/442203691

- Newton, Stella Mary. Fashion in the Age of the Black Prince. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1980. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1046293362

- Piponnier, Françoise and Perrine Mane, Dress in the Middle Ages. Tr. by Catherine Beamish. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/888880339

- Scott, Margaret. Fashion in the Middle Ages. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/756230586

- Sherrill, Tawny: “Fleas, Furs, and Fashions: Zibellini as Luxury Accessories of the Renaissance,” in Robin Netherton and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8157437211

- Sorabella, Jean. “Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/port/hd_port.htmn (August 2007)

- Wellman, Kathleen. Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1162061980

- Van Buren, Anne and Roger S. Wieck. Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/742330843

- Vaughan, Richard. Phillip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy. Vol. 3 of The Dukes of Burgundy. Woodbridge [UK]: Boydell Press, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1040841568

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1440-1449

Rulers:

- England: King Henry VI (1422-1461)

- France: King Charles VII (1422-1461)

- Spain: King Ladislaus (1440-1457)

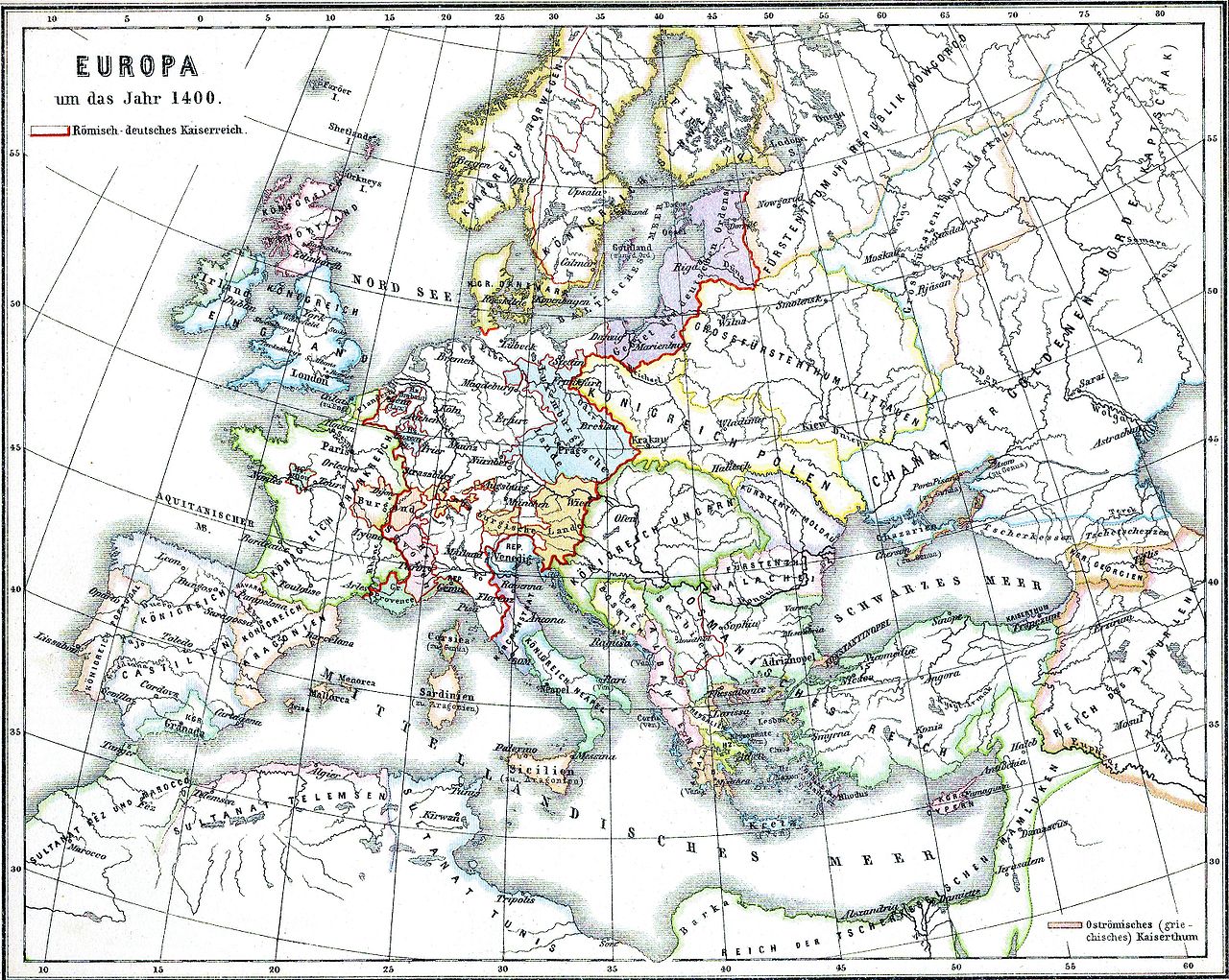

Europa 1400. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Events:

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 15th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.