OVERVIEW

In the 1730s the silhouette of both womenswear and menswear emphasized shape. At the same time, social events captured by famed artists allowed for the wealthy to display their sense of style and affluence.

Men’s and women’s dress of the 1730s was characterized by volume: women’s billowing gowns and petticoats were worn over dome-shaped panniers and the deep sleeve cuffs and side pleats of men’s coat skirts flared dramatically. Large-scale floral woven silk and embroidery designs were shown to advantage on the uncut panels of women’s dresses and the fronts of men’s coats and waistcoats. In France, Jean-François de Troy portrayed the idealized lifestyle of affluent Parisians in their richly appointed interiors and manicured gardens. In England, William Hogarth commented on the more sordid aspects of contemporary life.

Womenswear

The robe volante or robe battante that came into vogue in the 1720s remained dominant in the 1730s (Fig. 1). Constructed from four uncut panels of silk (two front and two back) that were seamed at the top of the shoulders, the gown hung loosely to the hem with the excess fabric controlled by pleats. The double box pleats at the back were the characteristic feature of what became “known all over Europe as the robe à la française,” until it went out of fashion in the 1770s (Ribeiro 38). Englishwomen, who found the unstructured robe volante too informal, adopted this gown, known as a sack, around the middle of the 1730s when it “became more a formal gown, fitted into the waist and with the bodice cut separately from the skirt and seamed to it” (Ribeiro 38).

In England, popular alternatives to the sack were the closed robe and the “nightgown.” The former was “made all in one piece, with the bodice fastened to the skirt by means of a front-fall opening, like a bib, which tied round the waist with the bodice then laced or pinned over it” (Ribeiro 33).

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (French). Robe Volante, ca. 1720-1730. Silk. Paris: Palais Galliera, 1987.2.20. public sale at Drouot Sales Hall. Source: Paris Musées

Fig. 2 - Charles Philips (British, c. 1708-1747). Tea Party at Lord Harrington's House, St. James's, 1730. Oil on canvas; 102.2 x 126.4 cm. New Haven: Yale Center fir British Art, B1981.25.503. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (British). Mantua, 1733-1734 (woven), 1735-1740 (made). Brocaded silk, hand-sewn with spun silk and spun threads, lined with linen, brown paper lining for cuffs, brass, canvas and pleated silk. London: Victoria and Albert Museun, T.324&A-1985. Given by Gladys Windsor Fry. Source: V&A

The women among the large group of elegantly dressed guests taking tea at the home of Lord Harrington in London are all in closed robes of solid and patterned silks, secured at the waist with a narrow buckled self-fabric belt (Fig. 2). Although the term nightgown may originally have referred to a kind of dressing-gown, “by the early 1730s, [it] appears in a puzzling variety of guises, made of rich and humble fabrics, and sometimes a closed and sometimes an open gown” (Ribeiro 40). By the end of the decade, it was “usually worn as an open robe, tight fitting at the waist” (Ribeiro 40) and in the last decades of the century, it “was to greatly influence the development of the robe à l’anglaise” (Ribeiro 40).

English women still wore the mantua that had come into fashion as an informal T-shaped gown in the 1670s. By the 1720s, however, the mantua became formalized with a more complicated construction; its previously loosely bunched up train that had created a generous bustle-like effect at the back began to be cut separately from the bodice and was worn looped up, as a sign of respect in the royal presence, rather than trailing on the ground as was the case in France (Ginsburg 145). These gowns demanded large quantities of fabric—a mantua and its matching petticoat dating to about 1731 to 1734 (Fig. 3) needed over 15 yards of the boldly patterned expensive silk (Ginsburg 146).

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (British). Stomacher, ca. 1720-1740. Silk, baleen, silver; hand-woven, hand-embroidered, hand-sewn. London: Victoria and Albert Museun, T.99-1962. Given by Mrs W. T. Alderson. Source: V&A

Fig. 5 - Jean François de Troy (French, c. 1679-1752). A Lady Showing a Bracelet Miniature to Her Suitor, ca. 1734. Oil on canvas; 64.77 x 45.72 cm. Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 82-36/2. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust. Source: Nelson-Atkins

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (French). Woman's Corset (Stays), 1730s-40s. Silk moire, silk cording and ribbons, linen lining; 38.1 cm (15 in). Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.57.24.1. Costume Council Fund. Source: LACMA

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (French). Cap Crown, ca. 1720-1740. Needle lace, point d’alençon, linen; 21.4 × 25.6 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.310.9. Gift of The Lady Reigate, in memory of her mother, Mrs. William Redmond Cross, 1979. Source: The Met

Both the sack and closed robe generally required a stomacher to fill in the front opening of the bodice. An example dating 1720 to 1740 (Fig. 4) embroidered in polychrome silk and metal threads and decorated with faux lacing features stylized flowers and foliage surrounding a man in exotic garb who stands above two fantastical birds—one of which reaches up for a tasty insect. It also illustrates the widespread vogue for chinoiserie evident in architecture and interior decoration as well as dress and furnishing textiles. The linen tabs at the sides of the stomacher would have been pinned to the corset and the silver-edged tabs at the lower front would have covered the top edge of the petticoat.

Jean-François de Troy’s painting, A Lady Showing a Bracelet Miniature to her Suitor (Fig. 5), depicts a young woman in the process of getting dressed in the presence of her admirer and assisted by her lady’s maid. Standing at her toilette table, she wears a closed robe volante of red silk heavily embroidered in gold thread with curvilinear foliate motifs graduated in size from the neck to the hem. Visible under the opening of the gown is her matching petticoat; the expansive shape of both garments confirms that she is wearing a pannier. Lace trims the neck and cuffs of her white linen chemise and her blue silk boned corset is laced across the front with matching silk ribbon (Figs. 5 & 6). Her young servant wears a less voluminous version of her mistress’s gown and the striped fabric is a warp-dyed silk called chiné à la branche (a technique in which the warp threads are dyed prior to weaving, creating a shadowy effect in the woven fabric). The direction of the stripes indicates that the seamstress used the straight grain of the fabric to stitch the body of the dress and the cross grain for the sleeves—typical of gown construction during this period. Both mistress and maid wear caps over their short, curled hair (powdered and unpowdered, respectively), although the former’s is decorated with a flower, a point of fashion at the time (Figs. 5 & 7).

Unlike (some of) their male counterparts, female servants did not wear livery during the eighteenth century and a well-dressed lady’s maid reflected the status of her wealthy employer (Figs. 5 & 20). Although social commentators complained vociferously that the practice caused unwanted social blurring, mistresses regularly made gifts of their unwanted or out-of-date garments, to their maidservants, who might wear them (perhaps slightly altered) or sell them as an additional source of income. In de Troy’s painting, the servant has covered her dress with a white linen bib apron to protect it while she completes her household duties and has added a white linen or cotton fichu for modesty.

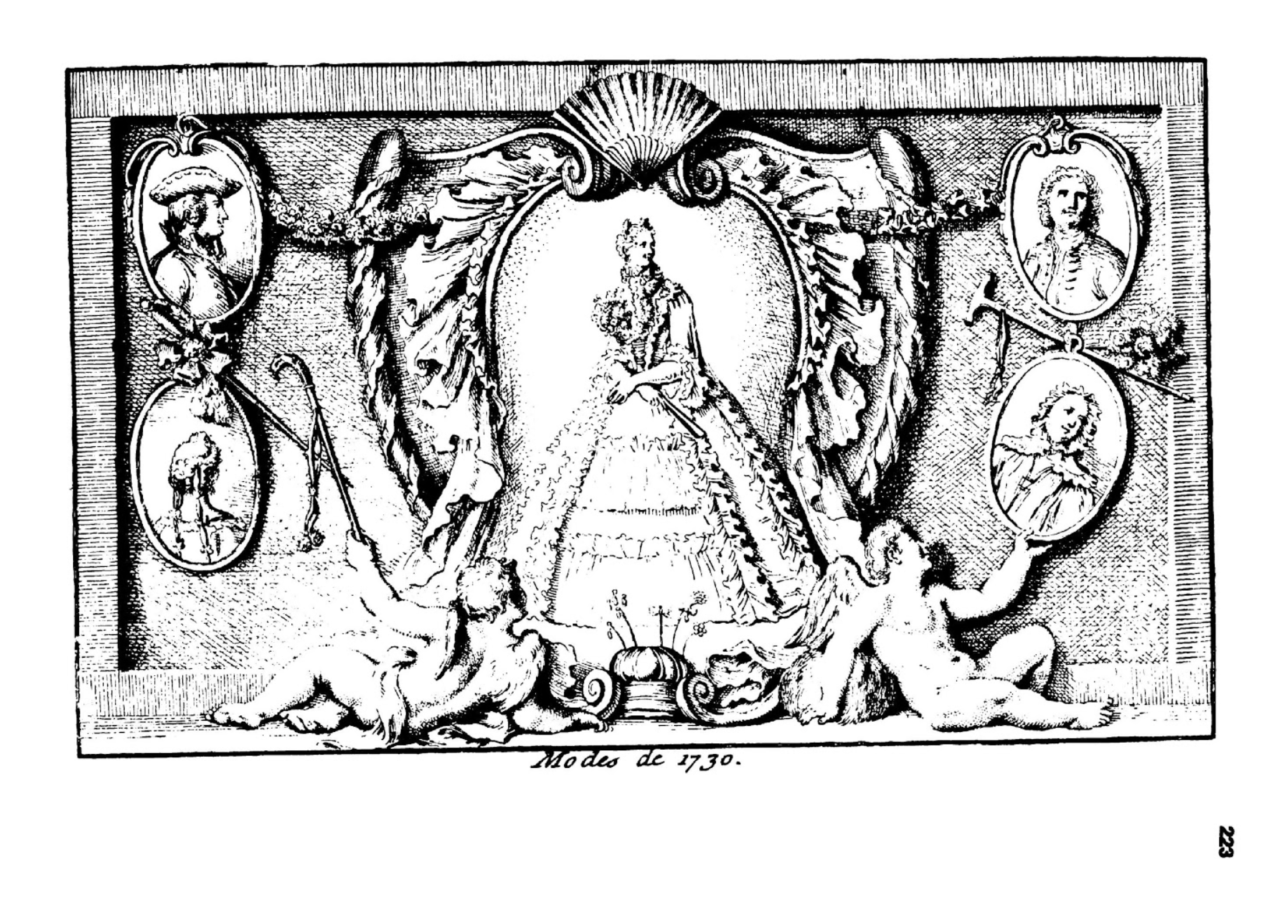

The Declaration of Love (Fig. 8), also by de Troy, shows fashionable young men and women in a garden setting, engaged in conversation. A gallant suitor proffers a nosegay to the object of his admiration, who is dressed in a silver-embroidered white silk robe volante open over a matching petticoat, while the woman to her right wears a closed version of the same gown in pink silk brocaded with a silvery-white floral pattern. The back view of the standing woman—whose hair is unpowdered—illustrates the flowing back pleats ending in a slight train characteristic of the robe volante, cuffs en pagode that the Mercure de France indicated in October 1730 were the still most popular, and the currently fashionable large-scale floral and foliate silk designs (2314). Although all the robes volantes in de Troy’s paintings are untrimmed, an illustration from the Mercure published in October 1730 (Fig. 9) shows a woman in a gown that appears to be more fitted at the bodice front and is generously decorated with self-fabric down the center front opening and across the petticoat (Figs. 5, 8, 9, & 10). Surviving dresses from the 1730s resemble those in the paintings and the decoration seen in the illustration is more typical of dresses from the 1740s and later (Fig. 1).

Small caps introduced in the 1720s to compliment the new, shorter coiffures remained in vogue (Figs. 2, 5, 7, 8, 10). Made of fine muslin (often embroidered) or lace, they were usually adorned with matching lappets and decorated with pastel-colored flowers or ribbons. In the same issue cited above, the Mercure reported that while little had changed in women’s hairstyles since the previous year, aigrettes made of false stones of various colors that had “a very gallant air” had recently come into fashion and did not require a large outlay of money (2316).

The hyper-feminine appearance of these stylish Parisiennes is reinforced by de Troy’s depiction of the central figure’s dainty foot covered in a pale blue silk stocking that matches the bows on her cap and sleeves and her white silk high-heeled mule that accentuates the erotic arch of her foot (Fig. 8). In October 1730, the Mercure observed that many women were wearing cotton stockings embroidered at the ankle with colored wools, while silk stockings were correspondingly decorated in gold or silver thread (2315). The elongated upturned toes and curved heels of the young woman’s mule reflect the sinuous lines associated with the rococo aesthetic (Fig. 11.).

Less likely to cause class confusion than a well-dressed lady’s maid were wealthy women who adopted refined versions of the casaquin (jacket bodice) and petticoat worn by working women and female servants relegated to the kitchen.

Fig. 8 - Jean- François de Troy (French, c. 1679-1752). The Declaration of Love, ca. 1731. Oil on canvas; 71 x 91 cm. Brandenburg: Brandenburg Museum. Source: MD

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown (French). Mercure de France. Modes de 1730, October 1730. Hathi Trust Digital Library. Source: Hathi Trust

Fig. 10 - Jean François de Troy (French, c. 1679-1752). A Reading of Molière or Reading in a salon, ca. 1730. Oil on canvas; 74 x 93 cm. New York: BGC Visual Media Resources Collection, 211440. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (English). Pair of Shoes, ca. 1735 (made). Brocaded silk, lined with leather, grosgrain ribbon and polished steel. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.60&A-1972. Source: V&A

Fig. 12 - Jean Siméon Chardin (French, c. 1699-1779). The Kitchen Maid, ca. 1738. Oil on canvas; 46.2 x 37.5 cm. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1952.5.38. Samuel H. Kress Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 13 - Designer unknown (Italian). Dress, ca. 1725-1740. Linen. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993.17a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1993. Source: The Met

The young woman peeling turnips in Jean Siméon Chardin’s painting of 1738 (Fig. 12) is dressed in a thigh-length, loose-fitting dull brown jacket bodice with blue-green wing cuffs, secured around her waist with a white linen apron, over a red petticoat; the two main garments are likely wool, while her blue and white fichu is probably cotton. Her practical cap is of plain white linen, rather than the delicate flower-bedecked lace seen on the women in de Troy and Phillips’ paintings (Figs. 2, 5, 8, & 10). A particularly fanciful example of a high-end casaquin and petticoat dating to the second quarter of the eighteenth century was surely worn for a special occasion (Fig. 13). Embroidered in wool threads on a linen ground, its “highly original ornamentation…combines chinoiserie imagery and allegorical figures of the Four Continents,” and while “the large, shaded flowers correspond to those in woven dress silks of the 1730s, the embroidery overall is more closely related to that seen in furnishing textiles” (Majer 38).

Throughout the eighteenth century, the fan was an obligatory accessory for the woman of fashion and an important instrument in the performance of gallantry and coquetry (Figs. 8 & 9). In 1711, the Spectator declared that “women are so armed with Fans as Men with Swords and sometimes do more execution with them” and imagined that the “gentle sex” (as they were frequently referred to) might be trained “to Handle your Fans,” “Unfurl your Fans,” and “Flutter your Fans” (quoted in Hart and Taylor 28). Although French fans (made in Paris) were considered the most desirable, London also had its fan makers; in the 1720s and 1730s, many of these were located near the Strand: “William Goupy…at the sign of the ‘Fann’ in Surrey Street…Joseph Jackson…at the ‘Golden Fan’ near Cecil Street and William West was at the ‘Fan and Gown’ nearby” (Hart and Taylor 35). Whether painted on paper, vellum or ivory, the most popular fan imagery included pastoral scenes (influenced by the fêtes galantes of Jean-Antoine Watteau), biblical and classical scenes, chinoiserie, and topical events (Hart and Taylor 29, 80) (Figs. 14 & 15 ). In October 1730, the Mercure humorously commented on the current use of “excessively large” and expensive fans, noting that, in some cases, the “little person” who carried such a fan was barely twice the height of her accessory.

Fig. 14 - Artist unknown (French). Folding Fan Painted with a Fete Champetre, ca. 18th century. London: The Fan Museum, LDFAN1999.11. The Fan Museum. Source: Fan Museum

Fig. 15 - Artist unknown (Italian). Fan Brise, ca. 1730. Painted pierced ivory, watercolour. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2199-1876. Source: V&A

The application of cosmetics among elite women was part of their dressing ritual and important in achieving contemporary notions of ideal female beauty. Aileen Ribeiro sums up the “perfect face [that] typified eighteenth-century ideas of regularity and proportion, being an oval shape with a small straight nose, slightly rosy cheeks and lips and a white complexion” (151) (Figs. 2, 5, 8, & 10). French women were acknowledged to “paint” more aggressively than their English counterparts; while in Paris in 1739, John Russel found the Gallic ladies’ faces to be especially unappealing with their “two globular spots…as fiery red as the orb of the sun when setting in a dusky evening” (quoted in Ribeiro 152). In October 1730, the editor of the Mercure seems to have mentioned the use of powder and rouge in order to chide his female readers. Referring to these cosmetics that women used to “highlight the brilliance of their beauty,” he warned them against relying too heavily on such products:

“We are far from wanting to criticize what the fair sex does to increase its allure. But we will not pretend that their natural beauty is improved; indeed, it suffers a great deal when they try to charm through an outrageous artifice that always lacks grace and the je ne sais quoi of simplicity and naiveté that earns them love and respect.” (quoted in Benhamou 18)

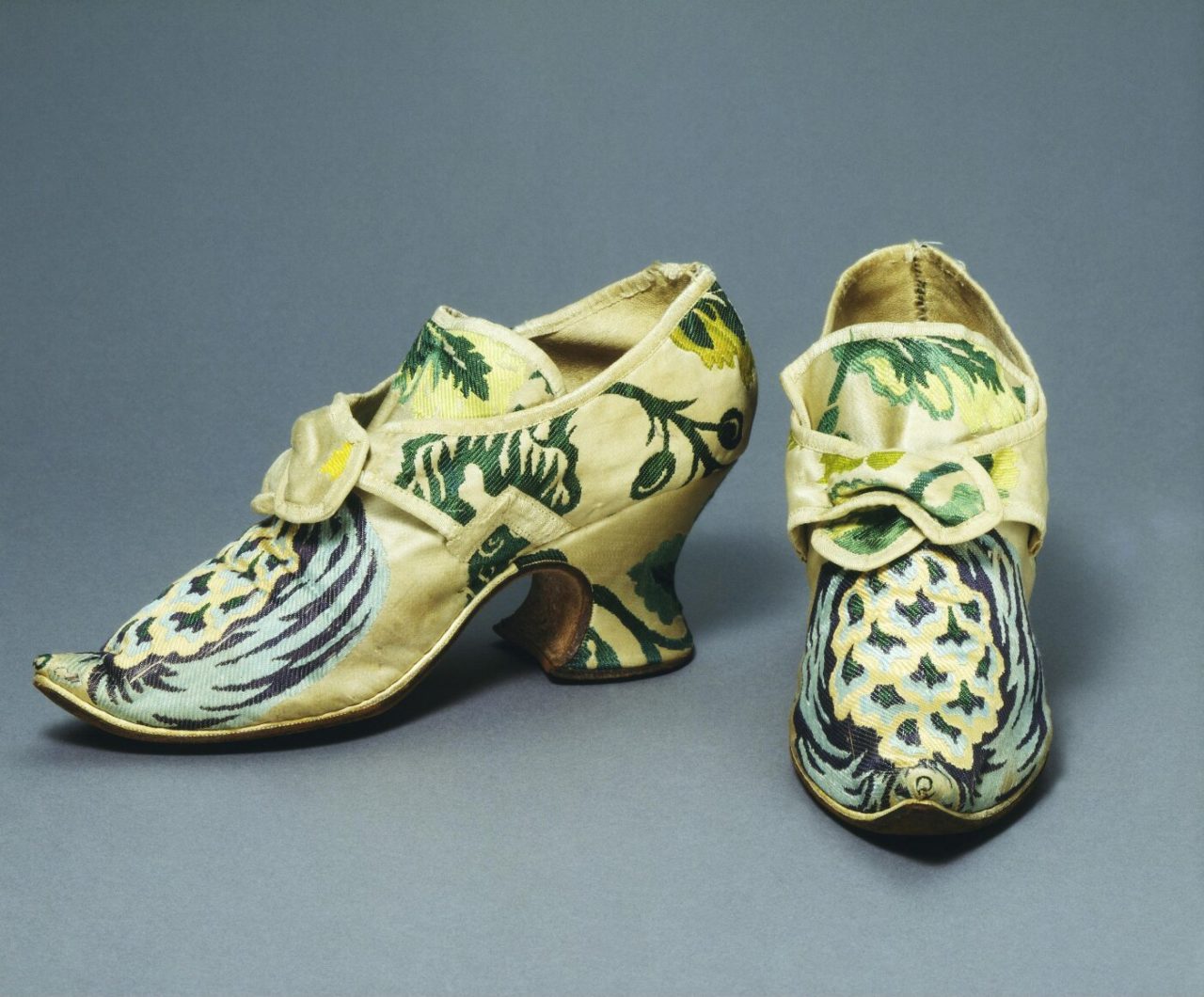

At the end of the 1720s, the dense mesh-filled designs that were typical of lace-patterned silks popular in that decade receded, floral motifs became more prominent, and a mirror repeat gave way to asymmetry (Figs. 3 & 16). Textile historian Natalie Rothstein characterizes silk design between 1733 and 1742 as “the quest for three-dimensional naturalism” (Rothstein 42). This shift was attributed at the time to a French designer named Courtois: “He was the first to attempt colouring by shading and pushed the understanding of light and dark and the art of colouring a fabric to an astonishing point” (quoted in Rothstein 42). Rothstein also highlights an innovation in the preparatory drawings of silk designs, generally credited to Jean Revel (1684-1751), “a painter who became a pattern-drawer,” that resulted in an increased ability to depict floral, foliate, and vegetal motifs more realistically. In a dovetailing technique known as points rentrés, individual wefts of different colors overlap, producing shaded and modeled forms with distinctly plastic, painterly qualities (Fig. 17) (Rothstein 43). Designers and weavers alike quickly exploited the possibility for enhanced pictorial effects and brocaded silks of this decade are filled with a profusion of lush vegetation, ripe fruits, shells, pastoral vignettes, and architectural elements (Fig. 18). Godfrey Smith, author of The Laboratory; or, School of Arts (1750), recalled when designers would give “the size of a cabbage to a rose” and “that of a pompkin [sic] to an olive” (quoted in Rothstein 43). In 1734, at the time of the wedding of Princess Anne of England to the Prince of Orange, newspapers reported that the most fashionable silks:

“were white paduasoys [plain-weave silk] with large flowers of tulips, peonies, emmonies, carnations & in their proper colours some wove in the silk and some embroidered.” (quoted in Ribeiro 42)

The prolific correspondent, highly proficient embroiderer, and artist Mary Delany (1700-1788) wrote that she purchased “a brocaded lutestring, white ground with great ramping flowers in shades of purples, reds, and greens” to wear to this formal event (quoted in Ribeiro 42). Although the impact of the scale and complexity of these designs was best suited to full garments, “naturalistic” silks were often used to fabricate women’s shoes; a pair in the V & A have been carefully matched over the arch (Fig. 11).

Fig. 16 - Designer unknown (British). Mantua, ca. 1732 (weaving), 1735-1740 (sewing). Silk, silk thread; hand-woven brocade, hand sewn. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.9&A-1971. Source: V&A

Fig. 17 - Jean Revel (c. 1684-1751). Woven Silk, ca. 1735. Silk. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.187-1922. Gift of W.J. Collins, Devon. Source: V&A

Fig. 18 - Antoine Pesne (French, c. 1683-1757). Sophie von Preußen mit ihrem Gemahl Markgraf Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg-Schwedt, ca. 1734. Oil on canvas. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Several designs from this period by Anna Maria Garthwaite, who produced hundreds of designs for Spitalfields weavers over the span of her thirty-year career, survive in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum (Fig. 19). Throughout the century, London-based silk designers were well aware of the latest trends from the French weaving center of Lyon and the luxuriant, vibrantly hued fabrics produced in Spitalfields in the 1730s (Fig. 3) confirm Smith’s observation that these silks attested to “the prevailing French fashion among our English ladies” (quoted in Rothstein 43).

Elite men and women reserved their top-of-the-line, expensive brocaded silks for formal or evening wear. For informal daywear, they selected plain and striped silks that were (relatively) more affordable. As Aileen Ribeiro points out, although not many examples survive from the early eighteenth-century, “plain silks were…suitable to be worn for taking tea, or playing cards or just for sitting in a garden or on a terrace” (Ribeiro 42) (Figs. 2, 8, & 10).

In Jacques Dumont’s portrait of Madame Mercier and her family (Fig. 20), all but one of the sitters wear plain and striped silk taffetas and velvets; the floral-patterned gown of the woman on the far right, holding a knotting shuttle, is probably a painted Chinese silk.

Fig. 19 - Anna Maria Garthwaite (English, c. 1688-1763). French Patterns, ca. 1735. Print design for woven silk. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 5974:7. Source: V&A

Fig. 20 - Jacques Dumont le Romain (French, c. 1701-1781). Madame Mercier surrounded by her family, ca. 1731. Oil on canvas. Paris: Grand Palais, RF511. Source: RMN Grand Palais

Mercier was wet nurse to Louis XV and this important royal position was “well paid, well pensioned, and highly honored” (Drake 948). Married to “a village horse-dealer… she eventually became the first femme de chambre of the Queen (Marie Leszczynska) [and] her husband obtained the position of controller-general of the Queen’s Household.” Portrayed 15 years after her ennoblement in 1716, Mercier and her offspring announce their recent social ascent and newfound wealth through the ostentatious simplicity of their clothing (Drake 948). At the left, the young man, who has turned his head to look casually over his shoulder at the viewer, flaunts his rakishly tilted gold-trimmed beaver hat, long queue, gold-trimmed scarlet wool coat with heavily rounded skirts, and a sword. In a not-so-subtle gesture, he has raised the back of his left foot to draw attention to his red-heeled shoes, associated with court dress. Although artists’ skills may have been more challenged by rendering the complex multicolored patterns of brocaded silks, they also liked plain silks “for the opportunities they afforded to display virtuosity in the painting of light on lustrous satins or shining taffetas” (Ribeiro 42).

Throughout the century, fabrics were seasonal; in October 1730, the Mercure described the variety of textiles for women’s dresses including, for warmer months, taffetas and cottons (presumably white) embroidered in vibrant colored silk threads, lined in pink and worn with white petticoats, and velvets, damasks, and plain satins that were popular for winter (2314 / Figs. 1, 2, 8, & 10).

Mercier was wet nurse to Louis XV and this important royal position was “well paid, well pensioned, and highly honored” (Drake 948). Married to “a village horse-dealer… she eventually became the first femme de chambre of the Queen (Marie Leszczynska) [and] her husband obtained the position of controller-general of the Queen’s Household.” Portrayed 15 years after her ennoblement in 1716, Mercier and her offspring announce their recent social ascent and newfound wealth through the ostentatious simplicity of their clothing (Drake 948). At the left, the young man, who has turned his head to look casually over his shoulder at the viewer, flaunts his rakishly tilted gold-trimmed beaver hat, long queue, gold-trimmed scarlet wool coat with heavily rounded skirts, and a sword. In a not-so-subtle gesture, he has raised the back of his left foot to draw attention to his red-heeled shoes, associated with court dress. Although artists’ skills may have been more challenged by rendering the complex multicolored patterns of brocaded silks, they also liked plain silks “for the opportunities they afforded to display virtuosity in the painting of light on lustrous satins or shining taffetas” (Ribeiro 42).

Throughout the century, fabrics were seasonal; in October 1730, the Mercure described the variety of textiles for women’s dresses including, for warmer months, taffetas and cottons (presumably white) embroidered in vibrant colored silk threads, lined in pink and worn with white petticoats, and velvets, damasks, and plain satins that were popular for winter (Figs. 1, 2, 8, & 10).

For upper- and middle-class women, the shift, corset and hoop petticoat constituted the three primary undergarments. In contrast to de Troy’s A Lady Showing a Bracelet Miniature to her Suitor (Fig. 3) that tastefully represents a young woman as she dons her garments, William Hogarth’s The Orgy (Fig. 21), from his series of paintings, The Rake’s Progress (1734), depicts late-night inebriation and dissipation in which the woman in the left foreground undresses in preparation for her performance on the table littered with goblets (Shesgreen pl. 30). She has already discarded her gown and boned corset and is about to remove her shoes and gartered stockings.

An engraving by Hogarth entitled Strolling Actresses in a Barn (Fig. 22) depicts a similarly chaotic behind-the-scenes image with two young female thespians in an enticing state of undress as they prepare to go on stage. At the center stands a young woman whose crescent half-moon hair ornament indicates that she will be playing the part of Diana, the goddess of chastity. Posturing theatrically with her collapsed hoop petticoat at her feet, she has left her chemise open over her bosom and has hiked up the hem, allowing a tantalizing view of her rounded thighs and stockinged calves with ribbon garters—“a sign of casual morality in Hogarth’s work” (Shegreen pl. 46). Kneeling in front of her, completing her coiffure, is Flora who exposes her right breast and whose petticoat appears to need mending in between two of the hoops. Two ropes tied to a rafter serve as laundry lines onto which members of the troupe have hung their body linens (including what looks like a man’s shirt) and accessories.

Throughout the eighteenth century, fashion was perceived as a powerful motor of consumption that benefited domestic economies, while at the same time, it was denounced for encouraging unnecessary expenditures and, in particular, a too-close imitation by the “lower orders” of their social superiors. A 1736 French almanac entitled L’Empire de la Mode (Fig. 23) conveys these critiques in its imagery and text. At the top, enthroned under a hoop-petticoat “baldequin” with flared coat skirt “wings,” sits Fashion wearing a large pannier, flanked by Vanity, symbolized by a peacock, and Inconstancy, symbolized by a windmill. At either side are cartouches commenting on fashion:

“Les fols Donnent cours aux Modes Les Sages n’affectent pas de s’en éloigner” (Fools give way to fashion, The wise ones do not affect to stray from it);

“Le Changement des Modes est une Grande ressource pour le Commerce” (The change in fashions is a great resource for commerce);

“Les Plus belles choses cessent de l’être des qu’elles ne sont plus à la Mode” (The most beautiful things cease to be so as soon as they are no longer in fashion); and

“La Mode degenere sitôt que le petit peuple a le moyen de la Suivre” (Fashion degenerates as soon as the common people have the means to follow it).

The inscription at the bottom reads, “Suivant la deliberation faitte au Magazin de l’Opera il a ête arrête que les paniers n’excéderont point la largeur d’un Carrosse acause des embaras qui en pouroient resulter” (Following the deliberation at the Magazin de l’Opera, it has been decreed that panniers will no longer be any wider than a carriage because of the problems that may result).

Fig. 21 - William Hogarth (English, c. 1697-1764). A Rake's Progress III: The Orgy, ca. 1734. Oil on canvas; 62.5 x 75.2 cm. London: Sir John Soane's Museum, P42. Source: Soane's Museum London

Fig. 22 - William Hogarth (English, c. 1697-1734). Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn, May 1738. Engraving in black on ivory laid paper. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1921.346. Gift of Horace S. Oakley. Source: AIC

Fig. 23 - François Desbrulins (French). Suivant la deliberation faite au Magazin de l’Opera, il a ete arrete que les paniers n’excederant point la largeur d’un Carrosse, ca. 1736. Engraving. Paris: National Library of France, Est. 18/78. Source: BnF Gallica

Introduced into England in 1709, the hoop was quickly taken up by French women. Although its overall shape and dimensions would change, it defined the female silhouette throughout Europe for the next six decades. In October 1730, the Mercure began its fashion column by unhappily acknowledging that the hoop, larger and fuller than ever, was evidence of the “the absolute power” of “la Mode” and was worn by women across the socio-economic spectrum in the both city and in the provinces.

Blaming the origin of this “outré” and irrational fashion on the English (usually the reverse was the case), the editor noted that hoops were more than three ells (approximately 135 inches) in circumference and usually reinforced with whalebone, which was flexible and light. Five bands of whalebone were standard; showier hoops—with eight bands—were called “à l’Angloise” and correspondingly costlier. Also affecting the price of these foundation garments were their materials; while glazed linen or taffeta hoops could be had for 10 to 50 livres, those ornamented with gold or silver galloon or embroidery demanded considerably more from the buyer’s purse.

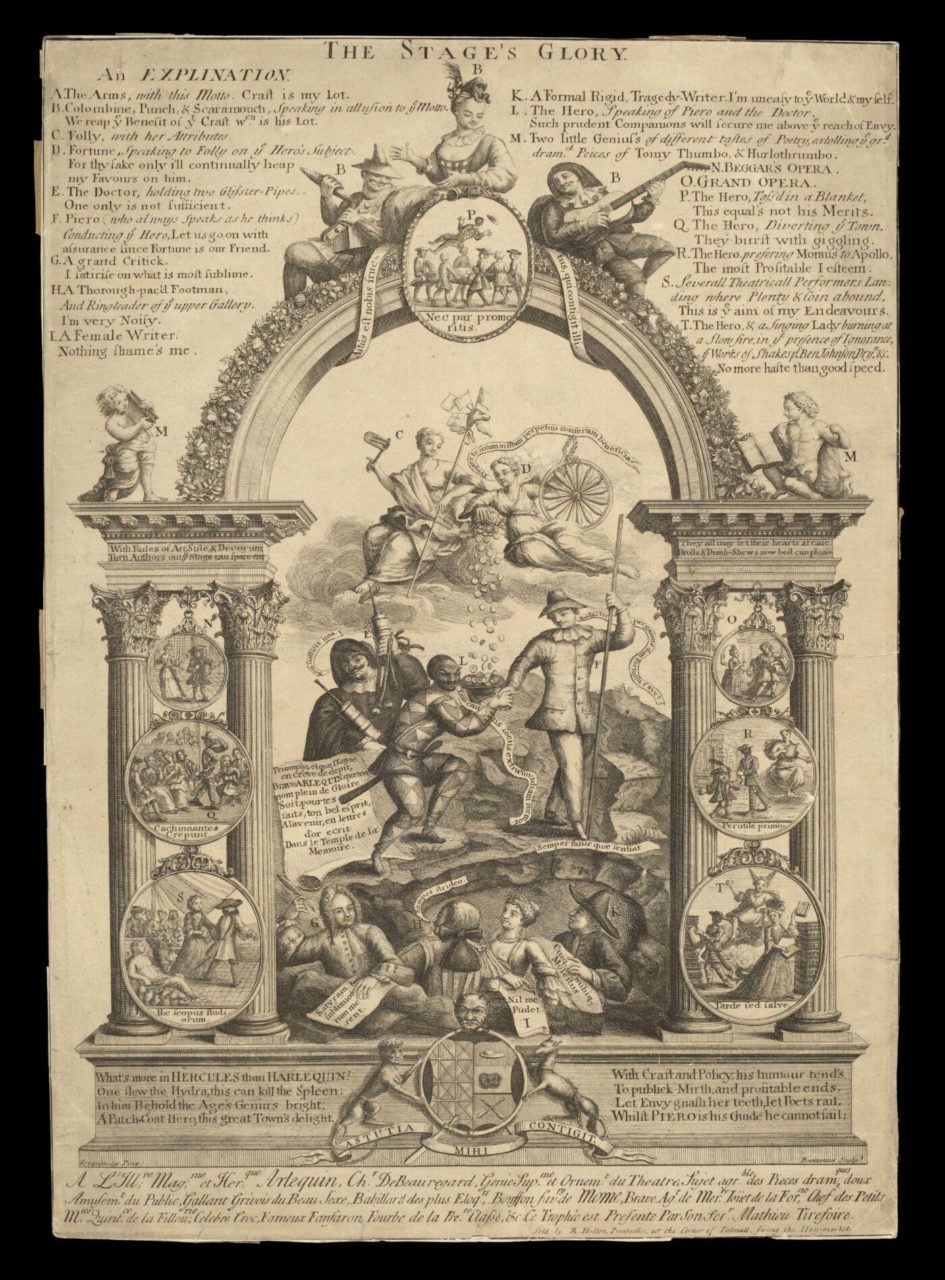

Fashion Icon: COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE costumed performers

Fig. 1 - R. Hulton (British). The Stage's Glory, ca. 1731. Etching, ink on paper; 26.8 x 17.6 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, S.3926-2009. Source: V&A

Originating in Italy, commedia dell’arte (Fig. 1) was a widely popular theatrical form in Europe from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. Actors wearing masks played stock characters, such as Arlecchino (a servant), Pulcinella (a servant or master), Il Dottore (head of the household), Pantalone (an older wealthy man), Columbina (a lively maidservant), and Pierrot (a servant or sad clown). Plots were also based on stock situations in which the actors improvised. Imported into France in the seventeenth century where it was known as the Comédie-Italienne, the genre had its greatest success outside of Italy. The colorful costumes of these entertaining social types (particularly characters like Harlequin and Columbine) and their exaggerated gestures appealed to artists in the early eighteenth century such as Jean-Antoine Watteau, Nicolas Lancret, and Phillipe Mercier, who depicted many scenes of these performers on stage (Figs. 2-4). Art historian Meredith Chilton notes that “while the commedia dell’arte waned as a form of theatre” over the course of the century, “its characters became popular in a broad range of artistic and cultural forms, particularly in the decorative arts” (Fig. 5) (Chilton 238).

Fig. 2 - Jean-Antoine Watteau (French, c. 1684-1721). The Italian Comedy [Die italienische Komödie], ca. 1716. Oil on canvas; 37 x 48 cm. Berlin: Berlin State Museums (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin). Source: JSTOR

Fig. 3 - Nicolas Lancret (French, c. 1690-1743). Italian Comedians (Actors of the Comédie Italienne), ca. 1730. Oil on canvas; 25.5 x 22 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, MI 1073. Source: Gallerix

Fig. 4 - Philippe Mercier (French, c. 1689-1760). Pierrot and Harlequin, ca. 1730. Oil on canvas. Source: Art

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (German). Harlequin Family, ca. 1738–40. Hard-paste porcelain. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982.60.297. The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982. Source: The Met

Although the distinctive commedia costumes did not directly influence fashion, the diamond-patterned patchwork garb of Harlequin and Columbine, all-black gown of the Dottore, and capacious all-white jacket and trousers of Pierrot were frequently worn for masquerade (Figs. 6-8). Throughout the century, men and women across social classes participated in this cultural phenomenon that (temporarily) subverted the established hierarchy and loosened its strict codes of conduct that governed interactions among peers and between those of greater or less rank. Many commentators and members of the clergy fulminated against what they perceived as a dangerous mixing of classes and the potential for licentious behavior that was encouraged by concealed identities.

The most lavish masquerades were held during Carnival in the weeks leading up to Lent between Twelfth Night and Ash Wednesday (Chilton 204). The city of Venice was renowned for its masked celebrations at this time of year and tourists from all over Europe flocked to participate in the many festivities (Fig. 9). However, these public and private gatherings occurred at other times of the year as well, and theatres that were both arenas of display and sites of make-believe often served as venues for masquerades, further blurring the boundaries between the “interplay of reality and illusion [and] the private and public persona” (Chilton 215) (Fig. 10).

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (German). Portrait of Margravine Sibylla Augusta as Harlequin, ca. 1700/1706. Tempera on parchment. London: Haughton Gallery. Source: Haughton Gallery

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Skirt for harlequin costume, probably worn by Ulrika Eleonora at one of the court's masquerades, late 17th century, ca. 1656-1693. Stockholm: The Royal Armoury, 29291 (3658: a). Source: LSH

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown. Harlequin Costume, first half or middle of the 18th century. Linen. Paris: Palais Galleria, 1920.1.1791a-e. Gift of the Société de l’Histoire du Costume. Source: Palais Galleria

Fig. 9 - Francesco Guardi (Italian, c. 1712-1793). The Casino [De speelbank (Il ridotto)], ca. 1720-1790. Canvas; 85 x 101.5 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, SK-A-3405. Source: JSTOR

Fig. 10 - Giuseppe Grisoni (Italian, c. 1699-1769). A Masquerade at the King's Theatre, Haymarket, ca. 1724. Oil on canvas; 24 x 44.7 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, P.22-1948. Source: V&A

The clever disguises that were intended to ensure anonymity at these events were far ranging. Charles-Nicolas Cochin’s watercolor (Fig. 11) depicting the masquerade ball held in honor of the marriage of Louis, Dauphin of France, to Marie-Thérèse of Spain in 1745 shows the crowded hall of mirrors at Versailles full of “Turks, Chinese, pilgrims, magicians, American ‘savages,’ and characters from the commedia dell’arte such as Harlequin, Pierrot and the Dottore” (Chilton 209).

(Louis XV attended the ball—where he first met Madame de Pompdour, who would become his maîtresse en titre—as a large yew tree along with seven other similarly costumed men of the court.)

Fig. 11 - Charles Nicolas Cochin (French, 1715-1790). Bal masqué donné pour le mariage du dauphin, dit bal des Ifs, 1745. Paris: Musée du Louvre, INV 25253. Source: Twitter

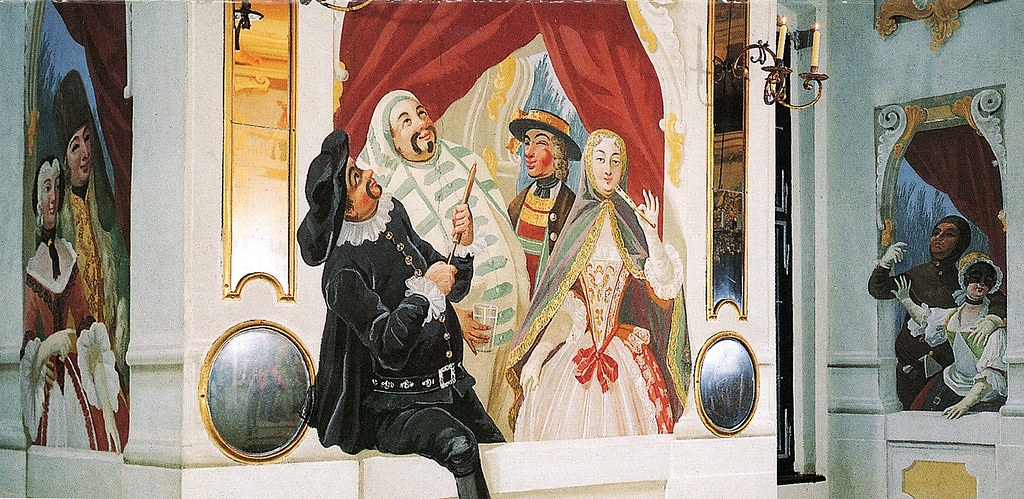

Commedia dell’arte figures appear in a series of trompe l’oeil frescoes depicting an exuberant masked ball by Josef Lederer, commissioned in 1745 by his patron, Prince Joseph Adam, in 1745 for the prince’s palace in the South Bohemian town of Český Krumlov (Figs. 12-14). The “theatre loges with second-floor balconies grouped on both sides of the room” reproduce the spaces in which masquerades were often held (Chilton 223). As Chilton describes,

“two magnificent guards” flank “the entrance doors to the Hall of Masks” [and] the masked revelers [including] fashionable ladies, gentlemen, and soldiers of rank mingle with characters from the commedia dell’arte—Scaramouch, Scapin, Pulcinella, Pierrot, Pantalone, the Dottore, the Captain, and Harlequin.” (Chilton 224)

Fig. 12 - Josef Lederer (Austrian). Masquerade Hall Frescoes Detail, ca. 1745. Fresco. Český Krumlov: Český Krumlov Castle. Source: Flickr

Fig. 13 - Josef Lederer (Austrian). Masquerade Hall Frescoes Detail, ca. 1745. Fresco. Český Krumlov: Český Krumlov Castle. Source: Flickr

Fig. 14 - Josef Lederer (Austrian). Masquerade Hall in the Castle in Český Krumlov, ca. 1745. Fresco. Český Krumlov: Český Krumlov Castle. Source: Country Life

In a further illusionistic twist, Lederer painted commedia costumes hanging on the balcony (Fig. 14) indicating that some of the other partygoers “were expected to duplicate some of the theatrical characters who were already represented on the walls” (Chilton 237-238). Seven of the surviving eighteenth-century theatre and masquerade costumes at Český Krumlov closely resemble the painted versions, suggesting that “for at least one masquerade party at Krumlov… the guests were dressed in costumes directly inspired by Lederer’s frescoes…[appearing like] paintings… to come to life” (Chilton 238).

With their playful theatrical associations, commedia dell’arte costumes evoked intrigue, transgression, and disruptive behavior that were fundamental to the experience of the masquerade.

Menswear

The three-piece suit worn with a linen shirt, knitted stockings, black leather shoes, and a three-cornered hat remained the staple components of men’s dress in this decade (Figs. 2, 8, 10, & 21 in womenswear). The side fullness of the coat that began to increase in the first decade of the century continued to gain in volume until the mid-century and was at its peak in the 1730s and 1740s (Fig. 1). Although the forms of menswear were the same on both sides of the Channel, “the plainness of male attire was from the beginning of the century a recognized feature of English dress, from the king downwards” (Ribeiro 21). As Ribeiro also notes, these differences between English and French dress “were to be the two most important influences on masculine clothing” (21-22) (Figs. 2 & 3). The three men and young boy in Hogarth’s Portrait of a Family (Fig. 3) all wear sober-colored suits accessorized with plain muslin ruffles, while the young suitor in de Troy’s painting “is the epitome of elegance and gentility in both deportment and clothing—the new bag wig with ribbon en solitaire, a stylish suit and red-heeled shoes, which imply that he has been at court” (Ribeiro 15).

Both the collarless coat with its full skirts stiffened with interlining and matching or contrasting waistcoat fastened down the center front (Figs. 1-7). The coat that required expert tailoring for its cut and fit “was the focal point of attention through the luxury and disposition of fabric and trimming… in the form of braid, embroidery, or lace” (Ribeiro 20) (Figs. 1, 2, & 5). From the mid-1720s to about 1750, “the most characteristic cuff was a closed cuff, keeping to the width of the sleeve, but coming almost up to the elbow” and known in England as a ‘boot sleeve’ (Ribeiro 18) (Figs. 3 & 4). The shape of the waistcoat was similar to that of the coat, “but without the side pleats, and with less width in the skirts” (Ribeiro 18) (Figs. 6 & 7). In the first half of the century, “many waistcoats had long sleeves, the upper sleeve matching the back, which… did not show”—demonstrating a judicious use of expensive fabrics (Ribeiro 18) (Figs. 6-8). Two formal waistcoats from the 1730s illustrate the similarity between the large-scale woven-to-shape and embroidered floral-and-foliate motifs in vogue during this decade (Figs. 6 & 7). Under the long skirts of the coat and waistcoat, the full-cut fly-front breeches were barely visible (Figs. 3 & 4).

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (French). Coat, ca. 1730-40. Silk cut and voided velvet, silver brocade. Paris: Les Arts Décoratifs - Musée de la Mode et du Textile, Louvre OAP 630.A. Photo by Patricia Canino. Source: Daily Beast

Fig. 2 - Charles Philips (British, c. 1708-1747). John Harvey Thursby (1709–1764), of Abington Abbey, ca. 1737. Oil on canvas; 124.5 x 100 cm. Northampton: Northampton Museums & Art Gallery, PCF62. on loan from a member of the Thursby family. Source: Art UK

Fig. 3 - William Hogarth (British, c. 1697-1764). Portrait of a Family, ca. 1735. Oil on canvas. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, YCBA/lido-TMS-407. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (European). Waistcoat, ca. 1730. Silk cut, uncut, and voided velvet (ciselé). Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.82.143. Gift of Catherine and Ralph Benkaim. Source: LACMA

Fig. 5 - Designer (French). Ensemble, ca. 1730. Wool, silk, and metallic thread. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.411a, b. Isabel Shults Fund, 2004. Source: The Met

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (Spitalfields (woven)). Man's Waistcoat, ca. 1734. Silk, brocaded with coloured silks and silver thread; 99 x 40.5 cm. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.72-1951. Source: V&A

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (French). Waistcoat, ca. 1730-1739. Silk satin, silver thread, spangles, silk thread; hand-sewn and hand-embroidered. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 252-1906. Source: V&A

Fig. 8 - Charles-Andre van Loo (French, c. 1705-1765). Portrait of an unknown in the reign of Louis XV, ca. 1730s. Oil on canvas. Versailles: Château de Versailles. Source: Wiki Art

Fig. 9 - William Hogarth (British, c. 1697-1764). A Rake's Progress II – The Rake's Levee, ca. 1734. Oil on canvas; 63 x 75.5 cm. London: Sir John Soane’s Museum, SM P41. purchased from the Fonthill sale, Christie's, 1802. Source: Art UK

The hat and—for a “man of quality”—the sword were integral accessories (Fig. 20 in womenswear). The most expensive hats were made of beaver-skin although “half-beavers” (in French, demi-castor) that were produced “by sticking beaver hair onto woollen felt [were] considerably cheaper” (Ribeiro 30) (Figs. 11 & 12). The three-cornered hat was correct for formal dress throughout the century and its trimming of “braid or lace, often with a feather fringe” was more important than the shape, which changed little (Ribiero 30).

The suitor’s shoes in de Troy’s The Declaration of Love (Fig. 8 in womenswear) have the new fashionably rounded toes that replaced the square-toes of the heavier shoes of previous decades. Throughout the century, men’s shoes were “fastened by straps from the heel leathers, buckled in front over the tongues” (Ribeiro 30). Buckles reflected the taste and spending power of the wearer. The most expensive were set with diamonds or made of silver, while “baser forms were of metal such as steel, pinchbeck, an alloy of copper and zinc imitating gold” (Ribeiro 30). The young lover’s up-to-date appearance includes his stockings that are worn with the tops concealed by the knee-breeches’ band, rather than rolled over as was done earlier.

In the privacy of the home, men wore dressing gowns that were roomy T-shaped garments or more fitted versions that fastened securely over the torso. Although the identity of the male sitter in a portrait (Fig. 8) by Carle Van Loo dating to the mid-1730s is unknown, he was intent on showing his wealth. He wears an extravagant brocaded silk dressing gown with large-scale flowers at the peak of their bloom and luxuriant fruits, lined in salmon-pink silk. In portraiture, these gowns were often left open to reveal more of a gentleman’s rich wardrobe. Here, his white silk waistcoat is also extensively woven with silk and gold threads and his unbuttoned fine linen shirt that adds to his carefully composed air of déshabille is trimmed with scallop-edged floral lace. Just visible are the single gold button gown closure at the neck and his untied black silk stock.

Clothes (and their absence) play a key role in Hogarth’s series of eight paintings, The Rake’s Progress (Figs. 9-12), completed in 1734 and engraved in 1735, that tell the cautionary tale of a young man who “rejects a life of work and virtue and uses his own and another’s wealth in follies and dissipations which lead to his ruin…preyed upon by the aristocracy, the businessman, the jail, the madhouse” (Shesgreen pl. 28). Following the sudden death of his miserly middle-class father, Tom Rakewell (Fig. 9) adopts an aristocratic wardrobe and lifestyle. At his morning lever (a ritual associated with the upper classes), he wears a stylish banyan (a fitted undress gown named for a Hindu trader) and turban-like nightcap as he receives his effete French dancing master, who will instruct him in proper comportment, a huntsman, and a fencing master, while a milliner, tailor, and wigmaker wait patiently in the corridor (Ribeiro 26; Shesgreen pl. 29). Later, “on his way to White’s [a well-known gentleman’s club in London] to recover by gambling what he has squandered by excess,” Rakewell (Fig. 10) is arrested for debt as he steps out of his sedan chair wearing a rich formal coat trimmed with passementerie and deep boot cuffs with large buttons, a powdered wig, and black silk solitaire at his neck. Over the course of his decline and oncoming madness, Rakewell loses the sartorial attributes of his brief upper-class status. In The Orgy, a bare-breasted prostitute (wearing the hat of Tom’s wigless friend at the back and upending sartorial gender norms) has unbuttoned his coat and shirt and Tom, perhaps, has undone the knee-bands of his breeches, exposing their fly-front opening (Fig. 21 in womenswear). His unsheathed sword is propped against his chair. In The Gaming House (Fig. 11), his wig—the symbol of male propriety and authority—lies on the floor, revealing his shorn head; and in the last scene, The Madhouse (Fig. 12), he appears wigless and half-naked—no longer a social being.

Fig. 10 - William Hogarth (British, c. 1697-1764). A Rake's Progress IV: The Rake Arrested, Going to Court, ca. 1734. Oil on canvas; 62.5 x 75.5 cm. London: Sir John Soane’s Museum, SM P43. purchased from the Fonthill sale, Christie's, 1802. Source: Art UK

Fig. 11 - William Hogarth (English, c. 1697-1764). A Rake's Progress VI: The Gaming House, ca. 1734. Oil on canvas; 62.5 x 75.5 cm. London: Sir John Soane's Museum, SM P45. Source: Art UK

Fig. 12 - William Hogarth (British, c. 1697-1764). The Rake’s Progress: VIII - The Rake in Bedlam, ca. 1732-1733. Oil on canvas; 62.5 x 75.5 cm. London: Sir John Soane’s Museum. Source: Kennedy Institute

Fig. 13 - After William Hogarth (British). A Midnight Modern Conversation, ca. 1732. Oil on canvas; 76.2 × 163.8 cm (30 × 64 1/2 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.351. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

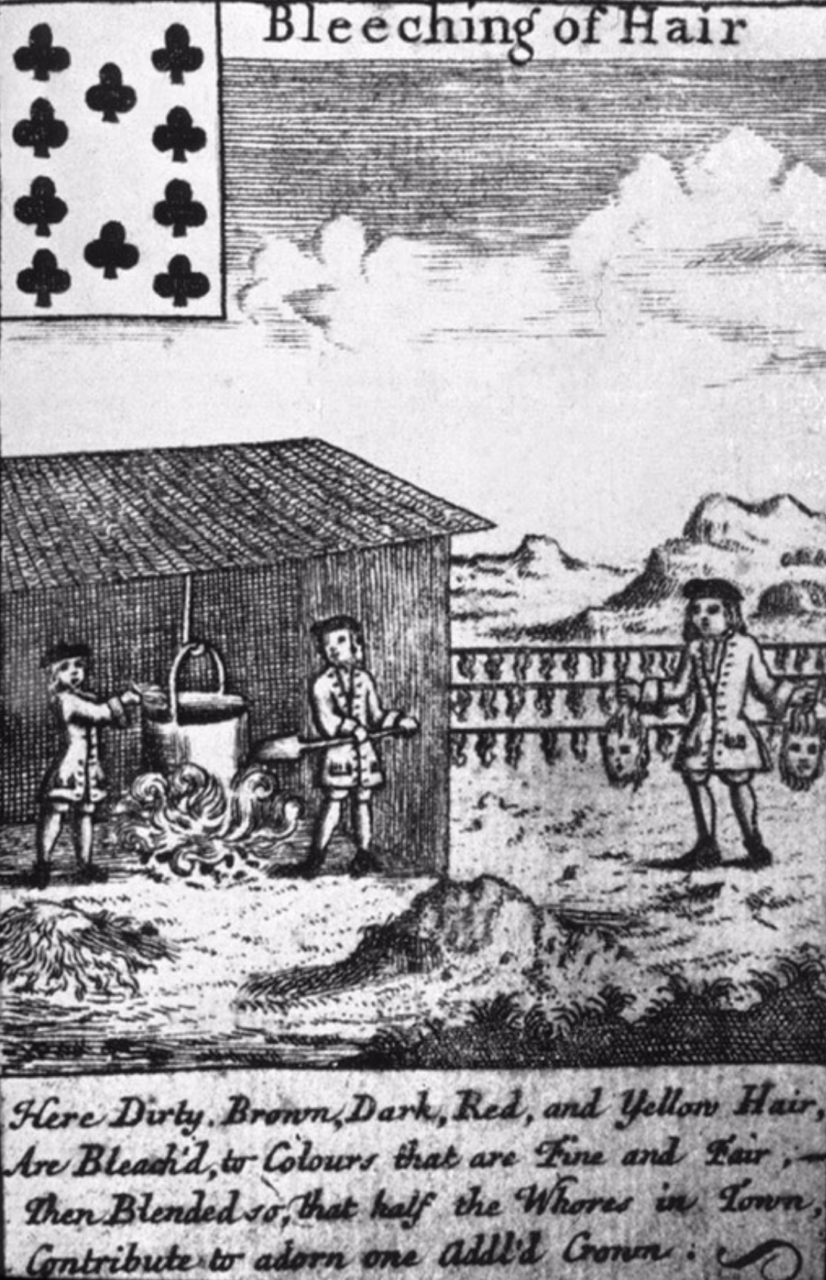

For the eighteenth-century man, his respectable self-presentation depended not only on his clothing but also on the correct wearing and appearance of his wig. Although women’s coiffures sometimes incorporated false hair, only men wore full wigs that generally required them to shave their heads. In portraits and scenes of polite society—like those by de Troy and Philips—both male and female sitters are well dressed and well behaved, without a hair (or wig) out of place (Figs. 2, 8, & 10). As historian Marcia Pointon argues,

“once it became customary for gentlemen to wear wigs, to appear without one was to expose oneself as eccentric, exceptional or deviant” (Pointon 117). In literature and art of this period, “the loss of the wig [was] a recurrent theme… connotative of loss of masculinity and potency” (Pointon 117) (Figs. 11-13).

As she further notes, anxieties regarding this gendered accessory and “register of socialized masculinity” extended to “the manufacture of the objects themselves” as well as their upkeep and cleanliness (Pointon 121-122). Although human hair was the most expensive and the most desirable, the source of that hair—that might come from prostitutes, plague victims, or corpses rather than virtuous young country women—was cause for concern; as a result, “the wig acquired a capacity to symbolize human filth and corruption that was widely exploited” (Pointon 121) (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14 - Artist unknown (English). Bleeching of Hair, ca. 1710. Print. New York: BGC Visual Media Resources Collection, 203094. Source: Google Books

CHILDREN’S WEAR

(BY SUMMER LEE)

Leading into the eighteenth century, attitudes about childhood were changing (Nunn 98). The shift was sparked by new philosophies emerging from the Age of Enlightenment. For example, in his 1693 publication, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, John Locke challenged long-held beliefs about best practices for child-rearing.

However, that was not reflected in childrenswear of the first half of the century. In the 1730s, traditions for childrenswear were not unlike those at the start of the century.

Infants were swaddled, as was the long-held European tradition (Tortora and Marcketti). Swaddling was the practice of tightly binding an infants’ limbs, so as to immobilize them (Callahan). The Victoria and Albert Museum possesses a finely embroidered swaddling band dated circa 1700-1750 (Fig. 1). Its elaborate floral embroidery indicates that this was a fashionable “outer swaddling band” (Victoria and Albert Museum).

In the early eighteenth century, babies typically outgrew the swaddling phase between two and four months (Callahan). They were then dressed in “slips” or “long clothes” (Callahan). These were ensembles with a fitted bodice and a very long, full skirt (Fig. 2) (Nunn 99). Babies also wore tight-fitting caps on their heads.

Once a child was becoming mobile, they transitioned into “short clothes” (Callahan). These ensembles allowed for greater mobility because skirts were cut at the ankle (Callahan). Bodices opened at the back and were boned or otherwise stiffened (Callahan). At this phase, toddlers typically had “leading strings” attached to the back of their bodice (Magidson). Leading strings were streamers of fabric used to protect young children from falling or wandering off (“Childhood”).

In his memoirs, English poet and historian William Hutton recalled of the year 1730:

“This Summer my sister Ann was born; and … the nursing was committed to me. I wished to see her in leading strings, like other children; but, being too poor buy, I procured a packthread string, which I placed under her arms …” (Hutton, 81).

When boys were deemed mature enough, they underwent a rite of passage known as “breeching” (Reinier). Breeching referred to the first time a boy wore bifurcated breeches or trousers, symbolizing his entrance into manhood. In the first half of the eighteenth century, boys were typically breeched between the ages of four and seven (Callahan). From that point on, boys during this time followed menswear fashions. Girls did not fully transition into adult dress until their early teens. However, elements of fashionable womenswear were incorporated into their dress as they aged.

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (French). Swaddling band, 1700-1750. Hand embroidered linen; 340.5 cm x 12.5 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, B.13-2001. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 2 - Joseph Highmore (British, 1692–1780). Mrs. Sharpe and Her Child, 1731. Oil on canvas. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.339. Source: Yale Center for British Art

Fig. 3 - Charles Bridges (English, 1672-1747). Benjamin Grymes (ca. 1725-1776) and Ludwell Grymes (ca. 1733-1795), 1735-1744. Oil on canvas; 100.33 x 125.73 cm (39 1/2 x 49 1/2 in). Richmond: Virginia Museum of History & Culture, 1981.9. Source: Colonial Virginia Portraits

Fig. 4 - William Hogarth (English, 1697–1764). A Children's Tea Party, 1730. Oil on canvas; 64.3 x 76.5 cm. Cardiff: National Museum Wales, National Museum Cardiff, NMW A 94. allocated by HM Government in lieu of tax, 1988. Source: Art UK

William Hogarth’s whimsical painting, A Children’s Tea Party, is an excellent example of 1730s children’s fashions (Fig. 4). A boy, who appears to be quite young, wears a menswear ensemble and plays a drum. His coat and breeches are a dark color, whereas his waistcoat is light. A young girl wears a white gown with pink leading strings and a white cap on her head. Two older girls wear gowns with fashionable floral fabrics and flowery headwear. They both wear translucent aprons, and one of their leading strings blows in the wind.

An English group portrait, circa 1730, depicts the four children of John Ivory Talbot: John, Thomas, Martha, and Ann (Fig. 5). Biographical information informs us that they are approximately ages thirteen, eleven, ten, and seven respectively. Both boys wear adult menswear ensembles, one in a very dark color and the other in beige. Thomas poses with a bow and arrow, similar to Benjamin Grymes in Figure 3. Martha and Ann wear pastel-colored gowns that mimic the fashionable womenswear silhouette. However, their bodices open and close at the back rather than the front, marking them as children.

An American painting from 1730 depicts a four-year-old girl named Susanna Truax (Fig. 6). The bold red and green stripes of Susanna’s dress are rather uncommon in portraiture from this time, giving the painting a striking quality. However, the cut of her ensemble is in line with popular childrenswear. While the bell-shaped silhouette of her skirt resembles womenswear, her bodice opens at the back and she wears a very sheer lace apron.

Fig. 5 - British (English) School. The Four Children of John Ivory Talbot, circa 1730. Oil on canvas. Lacock, Wiltshire: National Trust Collection, 996359. Source: National Trust Collection

Fig. 6 - Pieter Vanderlyn (American, c. 1687 - 1778). Susanna Truax, March 1730. Oil on bed ticking; 95.9 x 83.8 cm (37 3/4 x 33 in). Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1980.62.31. Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch. Source: National Trust Collection

References:

- Benhamou, Reed. “Who Controls This Private Space?: The Offense and Defense of the Hoop in Early Eighteenth-Century France and England.” Dress (Vol. 28, 2001): 13-22. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5525830337

- Buck, Anne. Dress in Eighteenth-Century England. London: B. T. Batsford, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1148934170

- Callahan, Colleen R. “Children’s Clothing.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed August 08, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1223089692

- “Childhood.” In European Renaissance and Reformation, 1350-1600, edited by Norman J. Wilson, 319-321. Vol. 1 of World Eras. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2001. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/45283259

- Chilton, Meredith. Harlequin Unmasked: The Commedia dell’Arte and Porcelain Sculpture. New Haven and London: The George R. Gardiner Museum of Ceramic Art with Yale University Press, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/47901269

- Chrisman, Kimberly. “Unhoop the Fair Sex: The Campaign Against the Hoop Petticoat in Eighteenth-Century England.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, Vol. 30, No 1 (Fall 1996) http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/703516389

- Cunnington, C. Willett. Handbook of English Costume in the Eighteenth Century. London: Faber, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/397113

- Drake, T. G. H. “The Wet Nurse in France in the Eighteenth Century.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine. (Vol. 8, No. 7) July 1940: 934-948.

- Ginsburg, Madeleine. “Ladies Court Dress: Economy and Magnificence.” In The V & A Album, 5, 1988: (142-154). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/860394968

- Hutton, William. The Life of William Hutton, F.A.S.S. Including a Particular Account of the Riots at Birmingham in 1791, and the History of His Family. Edited by Catherine Hutton. London: Printed for BBaldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1817. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1166863345

- “Introduction to 18th-Century Fashion.” Victoria and Albert Museum, January 25, 2011. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/i/introduction-to-18th-century-fashion/.

- Levey, Santina. Lace: A History. London: Victoria & Albert Museum; Leeds: W.S. Maney, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/847457626

- Magidson, Phyllis. “Fashion.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 344-348. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/872355070

- Majer, Michele. “Casaquin and Petticoat.” Recent Acquisitions: A Selection 1992-1993. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. Vol. LI, No. 2 (Fall 1993): 38. Mercure de France. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100116895 (Accessed 6/1/21).

- Nunn, Joan. Fashion in Costume 1200-2000. Bridgewater, NJ: Distributed by Paw Prints/Baker & Taylor, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/232125801

- Pointon, Marcia. Hanging the Head: Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteenth-Century England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/925097861

- Pratt, Lucy, and Linda Woolley. Shoes. London: V & A Publications, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/556898814

- Reinier, Jacqueline S. “Breeching.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 118. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/872355070

- Ribeiro, Aileen. Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/912425456

- Roche, Daniel. The Culture of Clothing: Dress and Fashion in the Ancien Regime. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28632365

- Rothstein, Natalie. Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Boston: Little, Brown, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/438246692

- Shesgreen, Sean, ed. Engravings by Hogarth. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1973. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868280259

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Sara B. Marcketti. “The Eighteenth Century 1700–1790.” In Survey of Historic Costume, 266–297. New York: Fairchild Books, 2015. Accessed August 07, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1150812358

- Victoria and Albert Museum. “Swaddling Band.” V&A Collections. Accessed August 08, 2020. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O62960/swaddling-band/.duction-to-20th-century-fashion/.

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/77806804

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600-1930. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/972515188

Historical Context

Map of Europe in 1730s. Source: Emerson Kent

Events:

- 1733 – John Kay invented the flying shuttle.

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 18th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.

![The Italian Comedy [Die italienische Komödie] The Italian Comedy [Die italienische Komödie]](https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/10.2307_community.15727171-1.jpg)

![The Casino [De speelbank (Il ridotto)] The Casino [De speelbank (Il ridotto)]](https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/10.2307_community.15665930-1.jpg)