OVERVIEW

1470s fashion emphasized the undergarment, creating a tighter silhouette that revealed the chemise underneath. At the same time, Spain had a great influence on other regions lead by fashion icon Charles the Bold who impacted both menswear and womenswear in his era.

During the 1470s the distinctive fashions of Spain first began to gain influence in Italy. The fit of women’s dresses and men’s doublets tightened, to the point that sleeves and bodices could no longer lace closed, revealing the undergarments. In most parts of Europe men’s doublets and outer garments had become so short that the hose had to be joined into a single garment. By the end of the decade, the high turret headdress of northern Europe had begun to decline. In Ferrara, duke Ercole I and his Spanish wife Leonora of Aragon presided over the most brilliant court in Italy, while Burgundy enjoyed a last burst of splendor under Duke Charles the Bold.

Womenswear

The basic undergarment remained the chemise of undyed linen, which was rarely seen when a woman was fully dressed. In Spain, however, the chemise was often revealed and decorated in a style that was originally Moorish, derived from centuries of Islamic civilization in the Iberian peninsula. Spanish chemises were called camisas, from the Latin, or alternatively, alcandoras, from the Arabic (Anderson 189). They were characterized by long pendant sleeves and narrow vertical strips of embroidered decoration, as seen in figure 1. Over the chemise went a dress, in Spain called the brial, or saya if it had a seam at the waistline. The two parts of a saya, the bodice (cos) and skirt (falda), could also be made separately (Bernis 49-50). The general fifteenth-century tendency to divide a garment into segments, each covering a part of the body (Newton 2-3), was especially strong in Spain. The woman standing at the foot of the bed in figure 1 wears a saya of a golden orange fabric, probably silk, whereas the woman sitting in front of her has a separate bodice and skirt of contrasting colors, and an underskirt (faldilla). Another distinctive feature is that the bodices are cut in a deep V-shape, coming to the point of the V at the center of the waistline. The triangular piece that fills in the V, larger and wider than the partlets seen elsewhere in Europe (Van Buren and Wieck 312), were called puertos in Spanish, and can be called stomachers in English (Bernis 36-50).

Whether made in one piece or two, the dress in Spain could be worn sleeveless, revealing the full length of the chemise sleeves underneath, or with separate sleeves that laced around the arm, as in the case of the seated woman; sometimes the sleeves are deliberately made too narrow to completely encircle the arm, and the chemise sleeves are allowed to spill out through the gap, as in the case of the standing woman. While the chemise was always made of washable linen, women’s dresses were typically of wool or silk.

Like Italy, Spain was a center for silk-weaving, and could produce silk velvets brocaded with gold, the “cloth of gold” worn by Salomé in figure 2. In this painting, one woman’s dress, made of red silk velvet, appears to be coming apart (Fig. 3). The sides of her bodice are too narrow to reach the edges of the triangular stomacher; black laces stretch across the front and are also seen at the shoulder connecting the sleeves, which allow the chemise to spill out below the elbow. Since so much of the chemise is revealed under the segmented parts of this dress, it was worthwhile to decorate it with black silk embroidery, called blackwork, which was also characteristically Spanish (Anderson 187). The most striking features of Spanish fashion for women in the 1470s, however, were the wooden hoops (verdugos) inserted into skirts to make them stand out away from the body. This fashion was attributed to Queen Juana of Portugal, consort of King Enrique IV of Castile, who devised it in an attempt to conceal an illegitimate pregnancy (Bernis 80). The verdugos could be stitched into channels on the exteriors of skirts and emphasized with contrasting trimmings, or they could be stitched into underskirts, or both, as seen in figures 1 and 2. While they did not catch on in other parts of Europe during this decade, other aspects of Spanish women’s fashion did.

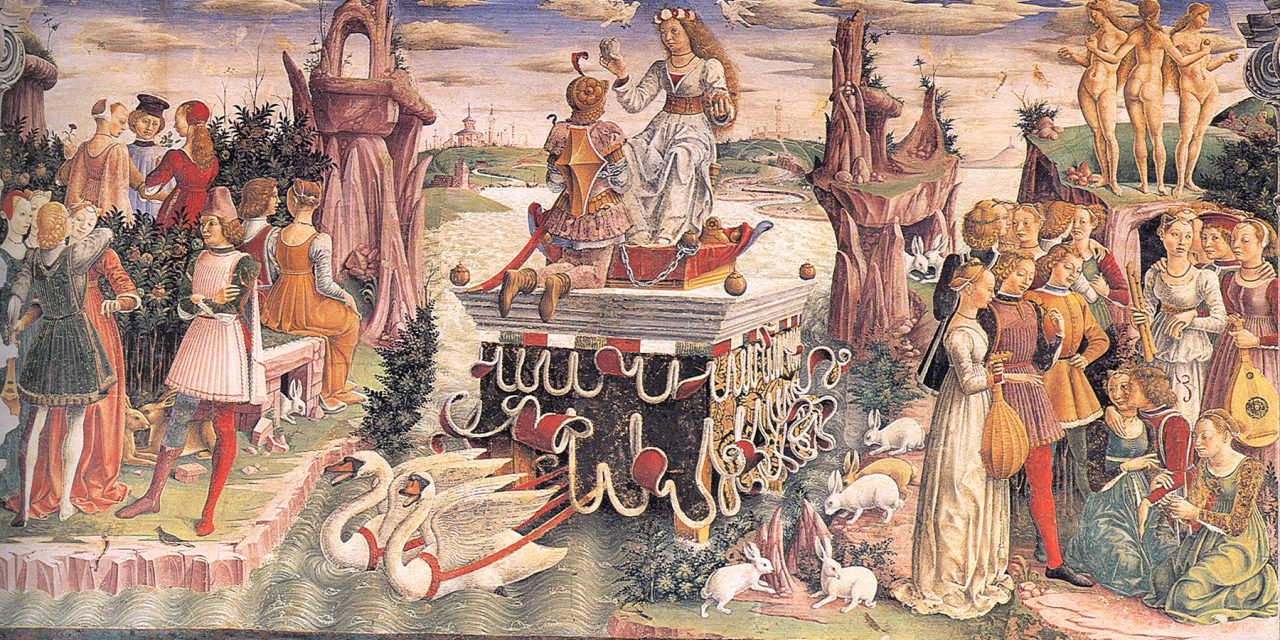

Spanish influence came into Italian fashion via the Aragon court at Naples. Since 1442 the dynasty that ruled Catalonia and Aragon, a kingdom in north-eastern Spain, had also ruled most of southern Italy and Sicily. One of the first places in northern Italy where Spanish influence was felt was Ferrara, due to the marriage in 1473 of Duke Ercole I to Leonora of Aragon, daughter of King Ferdinand of Naples (Herald 26). One of the frescoes that decorated the ducal family’s summer palace, the Palazzo Schifanoia, shows elegant young people celebrating the month of April by flirting and playing music, in the presence of Venus and the Three Graces (Fig. 4). The women wear dresses (gamurre, Herald 217) in the Italian style, with round scoop necklines in the front and back, and high waistlines. The standing woman in white, holding two flutes in her right hand, has drawn up the extra length in her dress over a hidden belt to form a blouson fold, as the ancient Greeks and Romans did with their garments (Boucher 123). Other dresses have sleeves in contrasting fabrics, indicating that they were separate and detachable. The Spanish influence is seen in the tight fit of the bodices and sleeves, that allow glimpses of the chemise underneath. Figure 5, another detail from this fresco, shows a young woman in a red gamurra that laces at the side; the laces have been pulled apart, showing the chemise underneath. The chemise is also escaping from the opening in her sleeve. Her companion, dressed in golden colored silk, has similar sleeves, but unlike the other young women in this scene, she wears an over-garment, called a cioppa (Herald 214-215) that continues from earlier decades. This cioppa has sleeves that have been slit to free the arm, allowing the sleeve of the gamurra to show, and leaving the sleeve of the cioppa to hang from the shoulder. This style of sleeve, called maniche à gozzi, is thought to have originated in Tuscany (Frick 192), but is seen in other parts of Italy as well.

Fig. 1 - Pedro Garcia de Benabarre (Spanish, fl. 1445-1485). The Birth of the Virgin, ca. 1475. Tempera, stucco reliefs, and gold leaf on wood; 127 x 93.5 cm. Barcelona: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 114750-000. Source: MNAC

Fig. 2 - Pedro Garcia de Benabarre (Spanish, fl. 1445-1485). The Feast of Herod, ca. 1470. Tempera, stucco reliefs, and gold leaf on wood; 197.5 x 125.7 cm. Barcelona: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 064060-000. Source: MNAC

Fig. 3 - Pedro Garcia de Benabarre (Spanish, fl. 1445-1485). Detail from The Feast of Herod, ca. 1470. Tempera, stucco reliefs, and gold leaf on wood; 197.5 x 125.7 cm. Barcelona: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 064060-000. Source: MNAC

Fig. 4 - Francesco del Cossa (Italian, 1436-1477). Detail from Allegory of April (The Triumph of Venus), ca. 1476-1482. Fresco; 500 x 320 cm. Ferrara: Palazzo Schifanoia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 5 - Francesco del Cossa (Italian, 1436-1477). Detail from Allegory of April (The Triumph of Venus), ca. 1476-1482. Fresco; 500 x 320 cm. Ferrara: Palazzo Schifanoia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 6 - Antonio or Piero Pollaiuolo (Italian, 1429-98/1441-96). Portrait of a Young Woman, ca. 1470-72. Oil and tempera on panel; 45.5 x 32.7 cm. Milan: Museo Poldi Pezzoli, 442. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 7 - Hans Memling (Netherlandish, 1430-1494). Portrait of Maria Portinari, ca. 1470. Oil on wood; 44.1 x 34 cm. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 14.40.627. Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913. Source: MMA

Italian fashion as in earlier decades is full of allusions to ancient costume, and this was no less evident in women’s hairstyles. In Italy women preferred not to hide their hair under elaborate headdresses. The young woman in red in figure 5 wears a simple matching cap (cuffia, Herald 215) that ties under her chin. Most of the others reveal their hair, which is arranged all’antica, inspired by ancient coins and sculptures, intertwined with strips of linen or silk called benda or binda (Herald 210). The seated woman in the right foreground of figure 4 has benda in her hair and is making another of the garlands of spring greenery that are already crowning some of her companions. A portrait by Pollaiuolo (Fig. 6) shows one of these hairstyles in great detail. Three elements are used – silk cord to bind the hair into a coil, which is then wound around the back of the head; the frenello (Herald 217) a jeweled hair ornament, often a string of pearls, as in this example; and the benda, the strip of fine linen that is seen covering the woman’s ear, held in place by a fine wire. At the crown of the head, the interwined hair accessories and ornaments are surmounted by a fermaglio, a brooch that could also be worn on the bodice or the sleeve of a garment (Herald 216).

Northern Europe continued to pursue different ideals of beauty and fashion in the 1470s. When Maria Maddalena Baroncelli of Florence married Tommaso Portinari, the manager of the Bruges branch of the Medici bank in 1470, she adopted the fashions of her new home, as seen in the portrait by Hans Memling (Fig. 7) that was probably completed soon afterwards (Metropolitan Museum). She wears a dress of darkest red velvet, trimmed in white fur along the wide V-shaped neckline, which is filled in by a black velvet partlet. The dress has fitted sleeves long enough to partly cover her hands, as was fashionable, and it is belted by a white sash. Her hair is completely hidden by her turret headdress (Van Buren and Wieck 319), a tall cone covered with black velvet and anchored in place by a velvet-covered wire, which is visible at the center of her forehead. It is covered with a veil of fine transparent linen hanging from the point. The turret was not a new fashion in the 1470s. Women in northern Europe had managed to wear this eccentric and yet captivating headdress since the late 1440s, but in this decade it was undergoing modifications, one of which can be seen in the portrait of Maria Portinari. On either side of the cone there are now two wide bands of fabric, usually black silk satin, or velvet as seen here, that extend down to the shoulders. This is called the frontlet (Van Buren and Wieck 304), and it may have had a practical function to balance and help adjust the turret. In 1470, the treasurer of Charlotte of Savoy, Queen of France, recorded the purchase of several lengths of black velvet, delivered to her tailor for the making of frontlets and “bonnets,” (the turret was also known as the haut bonnet in France) for the Queen, her two daughters, and a niece (Van Buren and Wieck 304).

However, the frontlet does not consistently accompany the turret later in the decade. Maria Hoose, the wife of a leading citizen of Bruges, wears a dress similar to Maria Portinari’s in her 1473 portrait (Fig. 8), but her turret is a truncated cylinder only a few inches high, and it has no frontlets. With embroidery of gold thread and pearls, it makes up in richness what it lacks in size.

The highest and most luxuriously covered turret seen in this decade belongs to Mary of Burgundy. As the only child of Duke Charles the Bold, Mary was the richest heiress in Europe and after her father’s death in January 1477, the reigning Duchess of Burgundy. In the book of hours commissioned for her in the same year (Fig. 9), she wears a turret covered with cloth-of-gold and a large veil of the finest linen as she sits by a window at her prayers. Through the window, we see a view of a church interior where she appears again, kneeling in prayer before the Virgin and Child. In both portraits, the turret is extremely high, and sans frontlet. The comparison of her dress to those seen in figures 7 and 8 does show that time has passed; the neckline is no longer V-shaped, but in a wide curve meeting in the front. A partlet is no longer necessary, but she does wear a gorget, a kerchief of transparent linen tucked inside the neckline of her dress (Van Buren and Wieck 305), the sash belt, which in this portrait is made of gold-brocaded silk, is now very wide. In Mary’s second appearance inside the church, her entire dress is of made of gold-brocaded velvet. It is possible that her turrets are extremely high not because of fashion, but because of her rank. At the Burgundian court, her English stepmother Margaret of York wore mid-high, very narrow turrets with angled tips and frontlets (Van Buren and Wieck 220).

Nevertheless at the end of the decade modest, truncated versions of the turret are more numerous than the tall cones, and in some sources, such as the French manuscript illuminated circa 1479 (Fig. 10), the frontlet seems to have smothered the turret with black cloth. Although the turret’s days were numbered, it would not be forgotten. Unfortunately, it has been remembered by an erroneous name – hennin, a term which should be applied, if at all, to the horn-shaped headdresses of the first half of the fifteenth-century. Turret, mitre, haut bonnet were the names used in France and French-speaking Burgundy where the fashion began (Van Buren and Wieck 318-319). “Steeple” has been used to describe its shape and proportions (Van Buren and Wieck 212). By any name, this most fanciful and romantic of fifteenth-century accessories has appeared on the heads of countless fairy-tale princesses.

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown (Flemish). Detail from Portrait of Maria Hoose, Triptych of Jan de Witte, ca. 1473. Oak; 74.5 x 38.5 cm. Brussels: Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, 7007. Source: KMSK

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown (Flemish). Mary of Burgundy at Prayer, Hours of Mary of Burgundy, Codex Vindobonensis, ca. 1477. Manuscript; 26.3 x 22.5 cm. Vienna: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, 1857 fol. 14v. Source: Feminae

Fig. 10 - Evrard d'Espinques (French, active 1440-94). Detail from The Birth of Tristan, Roman de Tristan, 1479-80. Manuscript; 44.5 x 31 cm. Chantilly: Musée Condé, MS 645, fol. 037v. Source: Initiale

Fashion Icon: Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (1433-1477)

Fig. 1 - Loyset Liédet (Flemish, born 1420). Detail of The Translator presents the book to Charles the Bold, Quintus Curtius, Fais d’Alexandre le Grant, ca. 1470. Manuscript. Paris: Bilbiothèque Nationale de France, BNF MS fr. 22547, fol. 1r. Source: Gallica

Fig. 2 - Gerard Loyet (Netherlandish, active 1466-1502). St. Lambert Reliquary, 1467-71. Gold and silver gilt; height 53 cm. Liège: Cathedral of St. Paul. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Charles the Bold (Fig. 1), who acquired his nickname in the nineteenth century (Vaughan 167), became Duke of Burgundy in 1467 upon the death of his father, Philip III “the Good”. In addition to the heterogenous Burgundian territories that his ancestors had acquired through strategic marriages, diplomacy and conquest, he inherited the largest treasury in Europe (Vaughan 3). Burgundy’s wealth came from its cities in Flanders and the Netherlands, and from what is today northern France. During his ten-year reign, traveling throughout his territories and often waging war to expand them, Charles used his wealth to project a public image of staggering luxury. On occasions such as a formal entry into a city, the signing of a treaty, an audience for ambassadors, or the annual festivities of the Order of the Golden Fleece, he staged what the chronicler Georges Chastellain called “the magnificences of Duke Charles” (quoted by Vaughan 179), spectacles designed to awe onlookers. An example occurred in January, 1474, when Charles formally took possession of the duchy of Burgundy at its capital, Dijon. He appeared in a suit of armor with the knee-caps and vambraces, the pieces that covered his arms, “encrusted with gems” (Vaughan 169). The gold Reliquary of St. Lambert (Fig. 2), a gift from Charles to the cathedral church of Liège in 1471, helps us to imagine his glittering armor. It shows him kneeling in front of St. George, holding the relic. At Dijon, over his armor, Charles wore an “Italian-style coat” (probably a giornea, see fig. 3 menswear), according to the Neapolitan ambassador Jehane Polimar, who wrote that it was “embroidered all over with the largest pearls” (quoted by Vaughan 169).

Charles liked to surround himself with Italians, such as his friend Francesco d’Este. He spoke Italian well, formed close relationships with ambassadors from Milan and Venice (Vaughan 162-165), and like his father, he consumed great quantities of Italian luxury goods. In 1475 he appeared at a similar ceremony at Nancy, to take possession of the duchy of Lorraine, which he had conquered from René of Anjou. The Milanese ambassador Johanne Petro Panigarola described him “dressed in a long ducal robe of crimson velvet lined with ermine and beaver with a hat on his head more or less in the form of a crown richly adorned with the largest pearls, diamonds, balas-rubies and carbuncles” (quoted by Vaughan 170). In the same year Panigarola described Charles at the publication of a treaty between Burgundy, Milan and Savoy:

“His lordship came to the church dressed in a long robe of cloth-of-old lined with sable, extremely sumptuous … On his head he had a black velvet hat with a plume of gold loaded with the largest balas-rubies and diamonds and with large pearls, some good ones pendent [sic], and the pearls and gems were so closely packed that one could not see the plume, though the first branch of it was as long as a finger.” (quoted by Vaughan 169-170)

Fig. 3 - Ghillebert de Lannoy (French, 1386-1462). Detail of The author presenting the book to Charles the Bold, 1450-75. Manuscript; 26.7 × 18.8 cm. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, BNF MS-5104 réserve, folio 14r. Source: Gallica

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown. Reconstruction of hat of Charles the Bold, 2008 (original before 1467). Switzerland: Château de Grandson. Source: Pinterest

By this decade, long garments for men were almost exclusively ceremonial, worn by court and civic officials. What made Charles’s robes “ducal” was the use of the most expensive fabrics, such as the cloth-of-gold robe seen in figure 3. The jewel-encrusted hats that made such an impression on Italian ambassadors were Charles’s versions of the plain ducal hats worn in Italy. While he pursued his goal of a royal or imperial crown, he had his hats made as crown-like as possible. In 1476, one of these hats was lost with Charles’s abandoned luggage, when his army had to make a hasty retreat at the battle of Grandson in Switzerland. It fell into the hands of the Swiss and its jewels were sold; based on a surviving drawing and a seventeenth-century print, the hat was reconstructed for a 2008 exhibition at the Bern Historisches Museum (Reynolds 490, Fig. 4).

The historian Richard Vaughan dismissed Charles the Bold’s sartorial magnificence as “the hat, the jewels, and all the other rigmarole designed to inflate the duke’s ego and project his image” (Vaughan 169). While it certainly impressed his contemporaries, who recorded that “every act of this prince is done with majesty and much ceremony” (Panigarola, quoted by Vaughan 170), it could not prevent the consequences of his grandiose ambitions and bad judgment, that led to his death in battle at the age of forty-three.

Menswear

Throughout Europe men’s dress began with a linen shirt and a pair of drawers, the basic undergarments that continued from earlier decades (Frick 160). One of the scenes in Francesco del Cossa’s Allegory of April is of a foot race, showing men running in their underwear (Fig. 1). In Italy, shirts were often made by nuns working out of convents, or by women who worked out of their homes. Lorenzo de Medici had a shirtmaker as a member of his household (Frick 40-41). The next layer of men’s clothing was the doublet (farsetto in Italy, Frick 160) and hose (calze) (Herald 210). The doublet was a fitted garment that opened down the front with laces or buttons; it could be made of a variety of fabrics, usually wool or silk (Frick 160). Some doublets in this decade, such as those seen in figure 2, the predella to an altarpiece for a church outside Florence, continued to have sleeves in the “Lombard” style, constructed in two parts with the upper sleeve cut full and gathered, joined to the fitted lower sleeve at a seam above the elbow (Van Buren and Wieck 168).

Fig. 1 - Francesco del Cossa (Italian, 1436-1477). Detail from Allegory of April (The Triumph of Venus), ca. 1476-1482. Fresco; 500 x 320 cm. Ferrara: Palazzo Schifanoia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2 - Domenico Ghirlandaio (Italian, 1449-1494). A Legend of Saints Justus and Clement of Volterra, ca. 1479. Tempera on wood; 14 x 39.4 cm. London: National Gallery of Art, NG2902. Bequeathed by Lady Lindsay, 1912. Source: NGA

Some had a row of eyelets midway down the upper sleeve, in order to lace on the pauldrons, the shoulder pieces of a suit of armor (Herald 216). The young men in figure 2 are supposed to be soldiers besieging a city; they have weapons but no armor. The contrasting laces threaded through the eyelets on their doublet sleeves are probably for decorative purposes only. For most of the fifteenth century the doublet had been a very short garment, barely reaching the hips; the hose, two separate leggings typically made of wool (Frick 167), had to be long enough to be laced to the hemline of the doublet, but typically there was a gap in front and back where the underwear would show.

In the previous decade, the shortening of the outer garments that were men’s third layer, worn over the doublet and hose, provided the impetus for the fusion of the hose into a single garment, sewn together at the back and provided with an additional piece, the codpiece (braghetta in Italy) in the front (Herald 211). The soldier in the center of figure 2 wears an outer garment, the sideless cape known as the giornea (Herald 218), and it is very narrow and quite short. As a result, by the 1470s most hose were constructed as a single garment. In Italy the taste for parti-colored hose, with leggings in contrasting colors, continued. Sometimes a single legging would be divided into upper and lower contrasting colors, as seen on the second soldier from the right in figure 2. A parti-colored garment or accessory in Italy was called adogato or divisato (Herald 209, 215). The colors and patterns could relate to a family’s coat of arms, or indicate livery supplied by a leader to his followers or servants, or they could simply be the individual’s choice (Herald 215).

The tight fit of these soldiers’ doublets and hose is fashionable in this decade, though their garments have not yet “split under the strain,” as Leonardo da Vinci put it (quoted by Herald 152), describing the effect of the trend, emanating from Spain, to make sleeves and bodices deliberately too narrow, exposing the shirt underneath. We can see that trend in Ferrara in Francesco del Cossa’s frescoes (Fig. 3). The young man in the center has a green doublet with Lombard sleeves; the lower, fitted part of the sleeve has seemingly split open to expose his shirt from the elbow to the wrist. In contrast to the soldiers in the predella painting, his parti-colored hose has attached soles, so that he does not need shoes (Herald 211-212). As his outer garment he wears a giornea in a delicate shade of pink, with scalloped trimming at the sides and fringe at the hemline. The belting of the giornea was an individual choice; it could be belted in the front only, with the back panel allowed to hang free, or all the way around as in the case of his companion to the left, or left unbelted.

Examples of unbelted giorneas can be seen in one of Mantegna’s frescoes in the ducal palace of nearby Mantua (Fig. 4). In this fresco in the Camera degli Sposi, Mantegna portrayed Ludovico III Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, greeting his son Francesco, who had recently been made a Cardinal. His older son Federico, at the far right, wears a yellow sbernia, a short cape worn slung over one shoulder (Herald 227); the lower edge has been lifted and draped over the left shoulder, revealing the green lining of what may be a reversible outer garment. The sbernia allowed for the alla togata gestures, recalling the drapery of the Roman toga, that Italians were fond of, but they also wore more tailored outer garments, such as the gonnella and its short variant, the gonnellino (Herald 218), a skirted over-doublet with a seam at the waistline, seen in the Allegory of April on the young man in gold (Fig. 5). In this decade it also becomes evident that Italians, like northern Europeans, may be padding their doublets and tailored outer garments to curve out in the front, in imitation of the breastplates of suits of armor. This padding gave men a military air, even when no armor was worn. The work of tailors and armorers was necessarily closely related (Newton 2-3).

Fig. 3 - Francesco del Cossa (Italian, 1436-1477). Detail from Allegory of April (The Triumph of Venus), ca. 1476-1482. Fresco; 500 x 320 cm. Ferrara: Palazzo Schifanoia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 4 - Andrea Mantegna (Italian, 1431-1506). Ludovico Gonzaga Meeting with His Son, the Cardinal, ca. 1474. Fresco (walnut oil on plaster). Mantua: Camera degli Sposi, Palazzo Ducale. Source: WGA

Fig. 5 - Francesco del Cossa (Italian, 1436-1477). Detail from Allegory of April (The Triumph of Venus), ca. 1476-1482. Fresco; 500 x 320 cm. Ferrara: Palazzo Schifanoia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 6 - Ercole di Roberti (Italian, c.1451-1496). Detail of The Miracles of St. Vincent Ferrer, 1473. Tempera on wood; 30 x 215 cm. Vatican City: Pinacoteca Vaticana, cat. 40286. Source: Musei Vaticani

Fig. 7 - Loyset Liédet (Flemish, born 1420). Detail of The Translator presents the book to Charles the Bold, Quintus Curtius, Fais d’Alexandre le Grant, ca. 1470. Manuscript. Paris: Bilbiothèque Nationale de France, BNF MS fr. 22547, fol. 1r. Source: Gallica

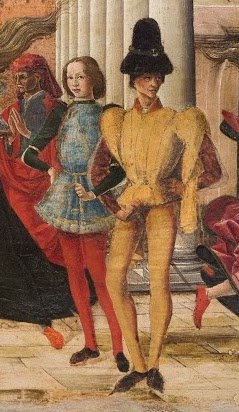

In all these Italian scenes we see men wearing a variety of hats, some simple round berettas (Herald 210), others taller conical caps that resemble those worn in northern Europe. Ludovico Gonzaga’s round hat with a narrow projecting brim is the so-called ducal cap (Herald 18), associated with governing authority. In Ercole di Roberti’s The Miracles of Saint Vincent Ferrer (Fig. 6), a hatless young Italian man, the tight sleeves of his doublet splitting open to show his shirt, is arm in arm with a man who looks very different. His high conical hat, wide padded shoulders and pointy poulaine shoes (Van Buren and Wieck 314) identify him as a man from northern Europe, probably from Burgundy where such fashions were taken to extremes.

A manuscript made for Charles the Bold and illuminated by Loyset Liédet (Fig. 7) depicts a range of Burgundian fashions for men, from the Duke’s long velvet robe trimmed with fur, which is loose and flowing, like the red robes and capes worn by the members of the Order of the Golden Fleece at their annual gatherings (National Library of the Netherlands), to the more fitted red robe worn by the courtier on the right. At the far left, another courtier wears a blue robe lined in fur that is open at the sides, allowing us to see his blue-grey hose underneath. It resembles the huque or journade (northern equivalent of the giornea, Van Buren and Wieck 309) of earlier decades, with the addition of sleeves. These men in long outer garments are more likely to hold government offices, but all of the men display the eccentricities of Burgundian fashion, such as the maheutres, padded spheres at the upper part of the doublet sleeves, as seen on the young man in the floral patterned doublet and bright green hose; this padding supports the extremely wide shoulders of the outer garments, that have sleeves slit at the back. While the Burgundians do not wear parti-colored hose, they do embroider one leg of the hose with emblems and mottos, as seen here. They wear tall conical caps and fling a second hat over their shoulder, or carry their hats perched on the ends of walking sticks, like the man with the green hose, who has one white and one black shoe, both of them pointy poulaines. A member of the Order of the Golden Fleece, his outer garment is a black sbernia. Some of these fashions, like the sbernia, the slit sleeves twisted up and wrapped around the shoulder, and the longer hairstyles, may spring from Italian inspiration. The general silhouette of northern European men, however, continues to be angular and highly distorted in the 1470s, but it is in harmony with northern women’s fashion, as seen in the background where a man and woman are sitting in a garden.

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Children in the 1470s continued to be swaddled at birth, as seen in figures 1 and 2, and dressed in layered tunics of linen and wool in their earliest years. As they grew older they were dressed more and more like adults. Francesco and Sigismondo (Fig. 3), the sons of Federico I Gonzaga, were approximately seven and four years old when Mantegna portrayed them, just as fashionably dressed as their elders.

Fig. 1 - Pedro Garcia de Benabarre (Spanish, fl. 1445-1485). The Birth of the Virgin, ca. 1475. Tempera, stucco reliefs, and gold leaf on wood; 127 x 93.5 cm. Barcelona: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 114750-000. Source: MNAC

Fig. 2 - Evrard d'Espinques (French, active 1440-94). Detail from The Birth of Tristan, Roman de Tristan, 1479-80. Manuscript; 44.5 x 31 cm. Chantilly: Musée Condé, MS 645, fol. 037v. Source: Initiale

Fig. 3 - Andrea Mantegna (Italian, 1431-1506). Ludovico Gonzaga Meeting with His Son, the Cardinal, ca. 1474. Fresco (walnut oil on plaster). Mantua: Camera degli Sposi, Palazzo Ducale. Source: WGA

References:

- Anderson, Ruth Matilda. Hispanic Costume 1480-1530. New York: The Hispanic Society, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/901098027

- Beamish, Gordon Marshall. “Ercoli I d’Este, Marchesse of Este, 2nd Duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio,” Grove Dictionary of Art, Oxford Art Online, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/494064218

- Bernis, Carmen. Trajes y modes en la España de los Reyes Católicos. 2 vols. Madrid: Instituto Diego Velázquez del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1978-1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/570368497

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume in the West. New York: Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1159814264

- Frick, Carole Collier. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes and Fine Clothing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62133195

- Herald, Jacqueline. Renaissance Dress in Italy, 1400-1500. London: Bell & Hyman, 1981. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/492385048

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Portrait of Tommaso di Folco Portinari (1428-1501); Maria Portinari (Maria Maddalena Baroncelli, b. 1456),” Catalogue Entry. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437487

- National Library of the Netherlands, “Order of the Golden Fleece.” https://www.kb.nl/en/themes/middle-ages/more-from-the-middle-ages/order-of-the-golden-fleece

- Newton, Stella Mary. Fashion in the Age of the Black Prince. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1980. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1046293362

- Reynolds, Catherine. “Charles the Bold. Bern, Bruges and Vienna.” The Burlington Magazine 151, no. 1276 (2009): 490-91. Accessed June 13, 2021. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/886838931

- Van Buren, Anne and Roger S. Wieck. Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/742330843

- Vaughan, Richard. Charles the Bold: The Last Valois Duke of Burgundy. Vol. 4 of The Dukes of Burgundy. Woodbridge [UK]: Boydell Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/671311

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1470-1479

Rulers:

- England:

- France

- Louis XI of France (1461-1483)

- Spain

- Isabella I (1474-1504 in Castilla)

- Ferdinand V & II (1475-1504 in Castilla, 1479 – 1516 in Aragon)

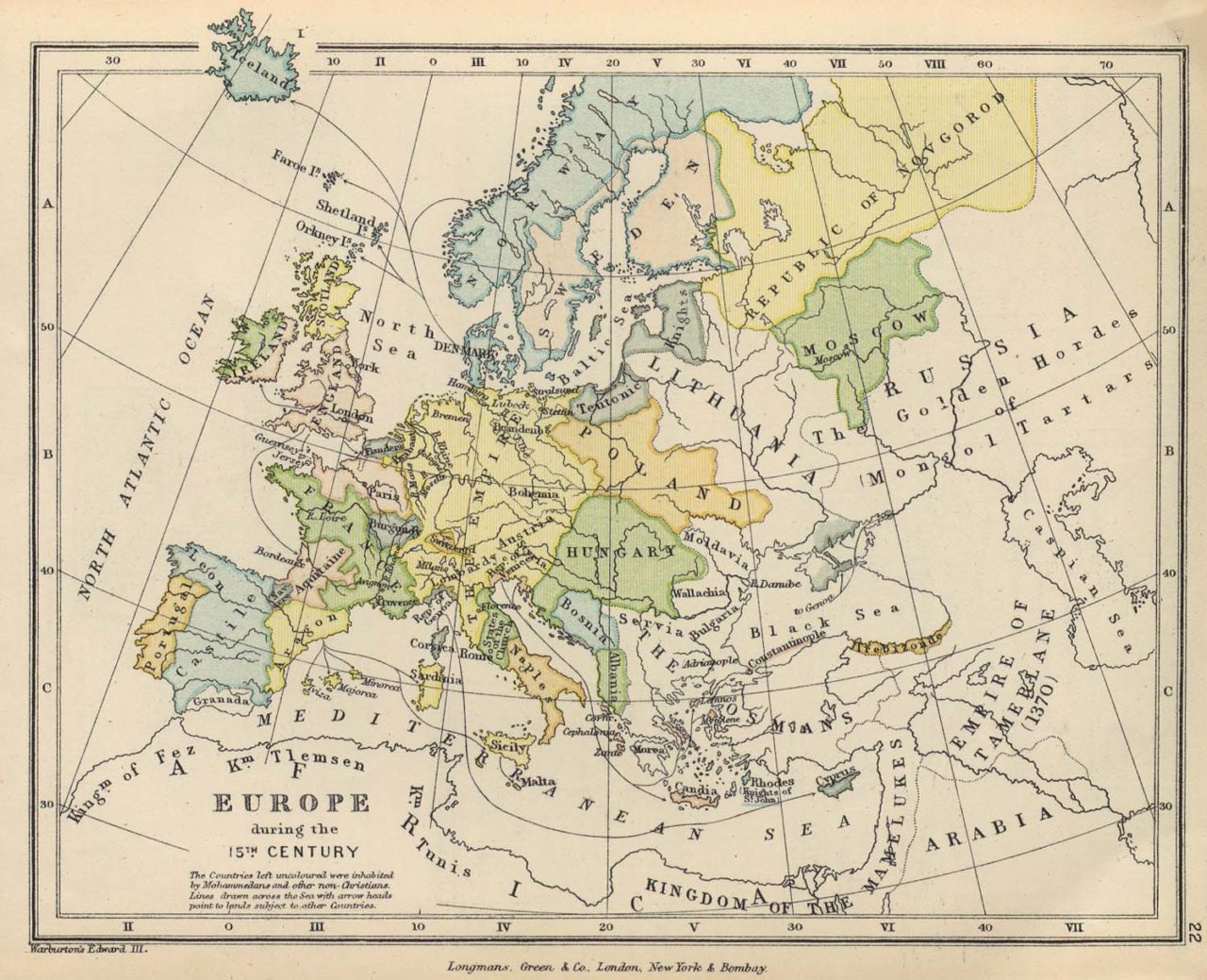

Europe during the 15th Century. Source: University of Texas Libraries

Events:

- 1473 – First edition of The Canon of Medicine

- 1474 – End of the Anglo-Hanseatic War

- 1476 – The new fashion is for slashing garments to reveal the lining or undergarments. Perhaps from the actions of Swiss soldiers following Battle of Grandson in 1476, when they patched tattered clothes with fabrics plundered from dead nobles.

- 1478 – Lorenzo de’ Medici becomes ruler of Florence

- 1478 – The Spanish Inquisition begins.

- 1479 – Ferdinand II ascends the throne of Aragon

- 1470s – Early versions of the farthingale appear in Spain as the verdugada or verdugado, a bell-shaped skirt stiffened with hoops of cane, or later, willow. Originally hoops are worn on the outer surface of the dress, later they go underneath the overskirt.

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 15th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.