OVERVIEW

Fashion at the start of the 1910s maintained elements of the previous decade, while beginning to move towards a simpler style. But mid-decade, World War I hit the Western world, causing fashion change to slow.

Womenswear

Fashion in the 1910s, like the decade itself, may be divided into two periods: before the war and during the war. World War I had a profound effect on society and culture as a whole and fashion was no exception. While changes in women’s fashion that manifested in the 1920s are often attributed to changes due to World War I, many of the popular styles of the twenties actually evolved from styles popular before the war and as early as the beginning of the decade.

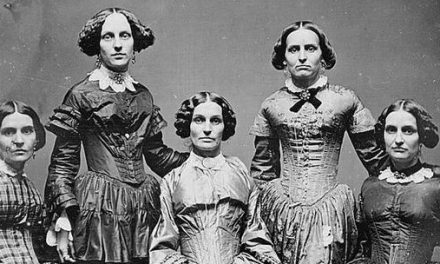

The 1910s opened with a softer silhouette than the decade before, which was dominated by the “S-shape.” While the contorted shape created by straight-fronted corsets had softened into a more natural silhouette, the style in the early years of the decade still had an emphasis on the bust that echoed styles of the previous decade. The ball gown by G & E Spitzer (Fig. 1) shows how the S-curve softened in the early part of the decade but still relied on the top-heavy look. As this S-shape began to disappear altogether, skirts began to taper towards the bottom, like the example by Doeuillet (Fig. 3) and a completely new style, that of a revived empire waist, emerged as well.

Fig. 1 - G & E Spitzer (Austrian). Evening dress, 1910-12. Silk, pearl, glass. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003.46. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 2003. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. At Rockaway Hunt Meet -- fashion mannikins, Between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915. 1 negative : glass; (5 x 7 in). Washington: George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-19041 (digital file from original negative). Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 3 - Georges Doeuillet (French, 1865-1929). Evening dress, 1910-13. Silk, rhinestones. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.1338. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Frederick H. Prince, Jr., 1967. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

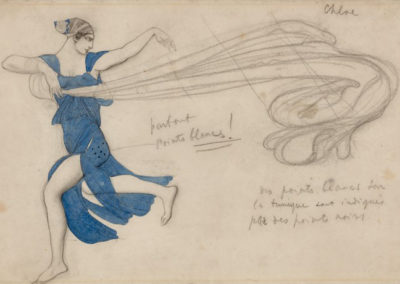

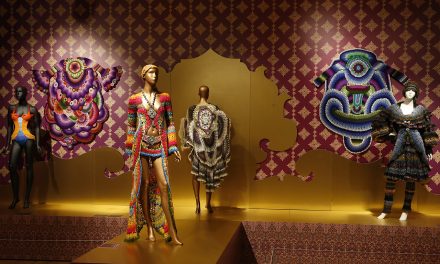

An important development at the beginning of the decade was the rise of Orientalism. The Ballets Russes performed Schéhérazade (a ballet based on One Thousand and One Nights) in Paris in 1910, setting off the craze. Paul Poiret helped popularize this look, which featured draped fabrics, vibrant colors, and a column-like silhouette. He even introduced “harem” pantaloons in 1911, a ballooning pair of trousers that only the most daring of women opted to wear. The fancy dress costume (Fig. 4) worn to his party “The Thousand and Second Night” epitomizes this style.

Poiret’s fashions dominated the first half of the decade if only because they were inventive and news-making. In 1911, he introduced the “hobble skirt” (Fig. 5) which narrowed so much at the bottom of the skirt that it made it difficult for women to walk. His striped dress from 1910 (Fig. 6) hints at this silhouette. He liked to claim that he had abolished the corset and, indeed, his loose chemise dresses no longer required the rigid undergarment, though other designers were also moving away from corseted looks at the same time. Another of his innovative silhouettes included the “lampshade tunic.” In this way, you begin to see how Poiret’s playful and inventive approach to fashion led to the popular styles of the twenties.

Fig. 4 - Paul Poiret (French, 1879–1944). Fancy dress costume, 1911. Metal, silk, cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1983.8a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Trust Gift, 1983. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Author unknown. Hobble Skirt Postcard, ca. 1911. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 6 - Paul Poiret (French, 1879–1944). Evening dress, 1910. Silk, linen. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.1289. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Ogden Goelet, Peter Goelet and Madison Clews in memory of Mrs. Henry Clews, 1961. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 7 - Photographer unknown (American). 5th Avenue Easter Parade, 1911. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 8 - USMC Archives from Quantico. New York Recruiting Office, 1918, 1918. Marine Corps Women's Marine Reserve (COLL/981), Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 9 - USMC Archives from Quantico. Final Review of Marine Reservists and Navy Yeoman, 1919, 1919. Marine Corps Women's Marine Reserve (COLL/981), Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections. Source: Flickr

Though Poiret made a formidable impression on early 1910s fashion, he was by no means the only prominent designer. Lucille, or Lady Duff Gordon, was a popular designer whose London-based business crossed the Atlantic to New York and Chicago at the beginning of the decade. French designer Jacques Doucet enjoyed popularity for his fluid designs, while Mariano Fortuny of Venice patented new processes of pleating and dyeing.

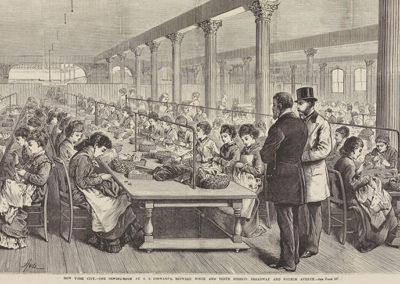

In 1914, the world was thrown into the “war to end all wars.” Tunics worn over skirts, like the ones seen in the picture of the Rockaway Hung Meet (Fig. 2), were a popular wartime fashion, as were simple, utilitarian clothing. Even French designers like Jacques Doucet produced simple, cotton designs during the war (Fig. 12). Women began to wear uniforms, including overalls and trousers, as they worked in munitions factories for the war effort.

Though the US didn’t enter the war until 1917, the war’s effect on fashion was already felt in France, the UK, and the rest of Europe. France had been the center of fashion for years and the war slowed, though did not stop entirely, production and distribution of new fashions. The Worth evening dress from 1916 shows that fashion was not entirely forgotten (Fig. 10), as does the image of women who came to enlist in the Marines in 1918 (Fig. 8). For women, military uniforms had elements of current fashion: the long skirts with tunics or jackets worn over them were reminiscent of civilian dress. The white uniforms of the female Navy Yeomen (Fig. 9) are especially evocative of styles worn by the Suffragettes.

After the war ended, simple styles continued and a “barrel”-like silhouette emerged. Fashion historian James Laver writes in Costume and Fashion: A Concise History that “the effect was completely tubular. Skirts were still long, but an attempt was made to confine the body in a cylinder” (230). This would eventually develop into the popular flapper look of the next decade and Poiret’s pleated skirt and cocoon coat (Fig. 11) strongly hint at what was to come.

Fig. 10 - House of Worth (French, 1858–1956). Evening dress, 1916. Silk, metal, rhinestones. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.3235. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. C. Oliver Iselin, 1961. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 11 - Paul Poiret (French, 1879–1944). Coat, 1918. Wool, rayon. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.201. Isabel Shults Fund, 2005. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 12 - Jacques Doucet (French, 1853–1929). Dress, 1918-19. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.51.97.10a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1951. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fashion Icon: Denise Poiret

“Slim, youthful, and uncorseted, she was the prototype of la garçonne. Poiret used her slender figure as the basis for his radically simplified constructions. In 1913 he told Vogue, ‘My wife is the inspiration for all my creations; she is the expression of all my ideals.’ If Poiret was the prophet of modernism, Denise was its most compelling incarnation.” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Denise donned her husband’s controversial harem pants (with a wired skirt) to an extravagant costume party called “The Thousand and Second Night” (a clear reference to the popularity of Schéhérazade) in 1911 (Fig. 1). The same style was later used in costumes he produced in 1913, and they made their debut outside of the realm of costume later that year. Together with her husband, the duo epitomized avant-garde fashion in the 1910s.

Menswear

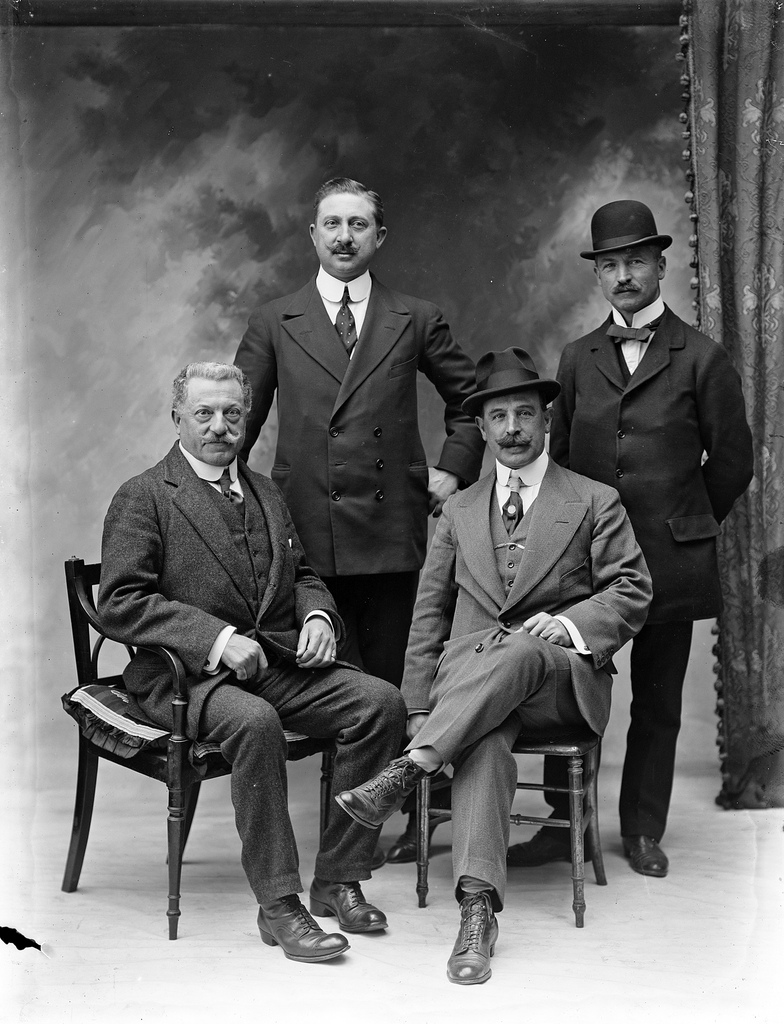

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (Irish). A group of four men from the Imperial Hotel, The Mall, Waterford., May 27, 1914. Dublin: National Library of Ireland. NLI Ref.: POOLEWP 2548. Source: Flickr

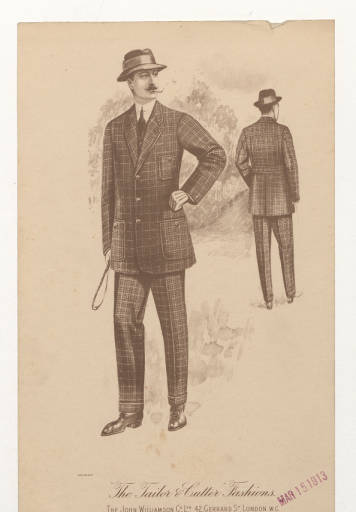

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. The Tailor and Cutter Fashions, 1913. New York: The Met, Costume Institute Fashion Plates. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

“trousers tended to be rather short and very narrow, and young men were beginning to wear them with permanent turn-ups and with a sharp crease in front, which had become possible since the mid 1890s with the invention of the trouser-press.” (221-222)

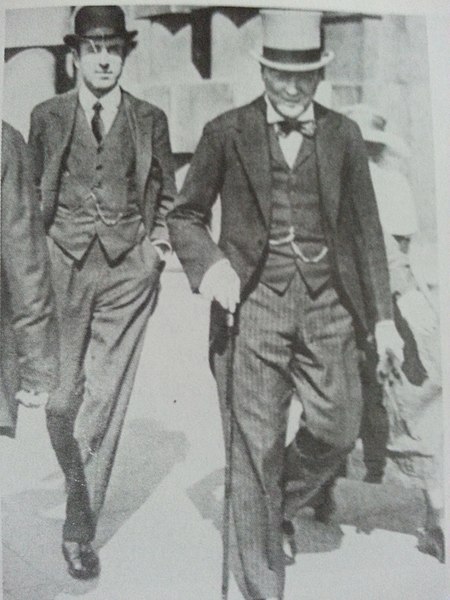

The lounge suit typically consisted of a sack coat, a waistcoat (vest), and trousers. Collars were worn starched and high on the neck. It was referred to as a “lounge suit” because it was far less formal than the suit worn with a frock coat. Though it was worn more frequently in the 1910s, it was previously a well-to-do man’s least formal suit, one that would have been worn to lounge in his home. The lounge suit was often worn with a Homburg hat, a felt hat with a dent down the top, or a bowler hat. Men of the upper-classes continued to wear top hats. An image showing Winston Churchill and his cousin Lord Londonderry in 1919 shows how the morning suit differed from the lounge suit (Fig. 4).

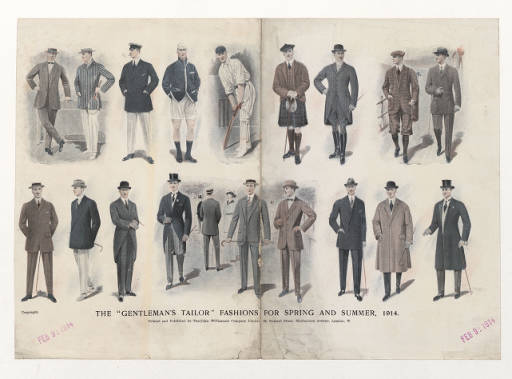

While the lounge suit enjoyed popularity on a day-to-day basis, the frock coat and morning coat continued to have prominence for formal day events. Evening wear was dominated by dark tailcoats, worn with a waistcoat and trousers. However, the less formal tuxedo was also an acceptable form of evening wear. Men sported quite a range of suits, sportswear, and evening wear for every occasion (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. The Gentleman's Tailor, Fashions for Spring and Summer, 1914. New York: The Met, The Costume Institute Fashion Plates. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

Fig. 4 - Angevin Knight. Winston Churchill and his cousin Lord Londonderry, 1919. Source: Wikimedia

Like womenswear, menswear saw a divide between before World War I began and during/after the war. Of course, many men joined the war effort by enlisting in the military. The Victoria and Albert Museum writes, “from 1914 to the end of the decade, many men were photographed in military uniform” (History of Fashion 1900-1970).

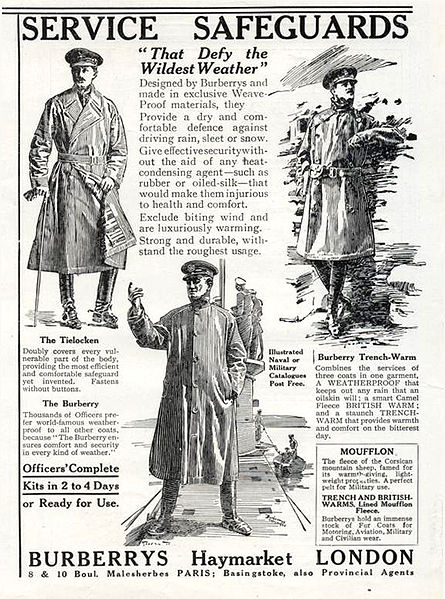

Though men’s fashion would return to the three-piece suit after the war, the conflict did have a lasting effect on both men and women’s fashion. Though part of their uniform and not a fashion statement at the time, the trench coat saw its rise (and was even given its name) in the desperate conditions on the front in World War I. British officers, who outfitted themselves, began to buy the coats that had been developed in the mid-nineteenth century as a functional part of their uniform. Lighter than the coat issued by the British army, water resistant, and a khaki color, the coats helped keep officers warm and dry. Burberry (Fig. 5) and Aquascutum sold these coats to both men and women during the war. It was utilitarian at the time but would later be adopted by Hollywood, providing the garment with a lasting legacy that is still felt today.

Fig. 5 - Burberry (British). Burberry Advertisement 1916, 1916. The Sphere. Source: Wikimedia

CHILDREN’S WEAR

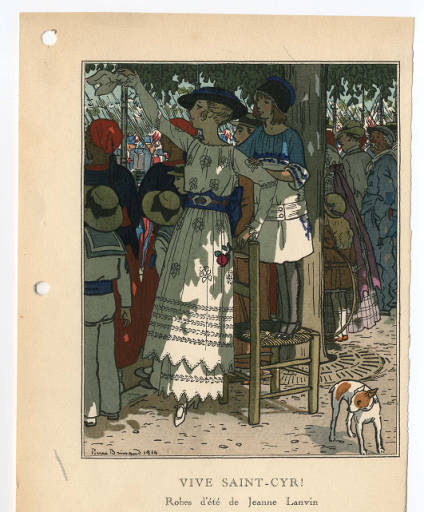

Fig. 1 - Jeanne Lanvin (French, 1867-1946). Robes d'été de Jeanne Lanvin, 1914. New York: The Met, The Costume Institute Fashion Plates. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

Fig. 2 - David Knights Whittome (British, 1876-1943). Carnegy children, 15 December, 1916. Source: Wikimedia

“By around the WWI era, many girls were wearing plainer dresses that ended above the knee (often showing long knickers underneath!), were fitted at the waist and had three-quarter length sleeves.” (Moore)

Young girls had begun to wear styles that were simpler and less like mini versions of womenswear.

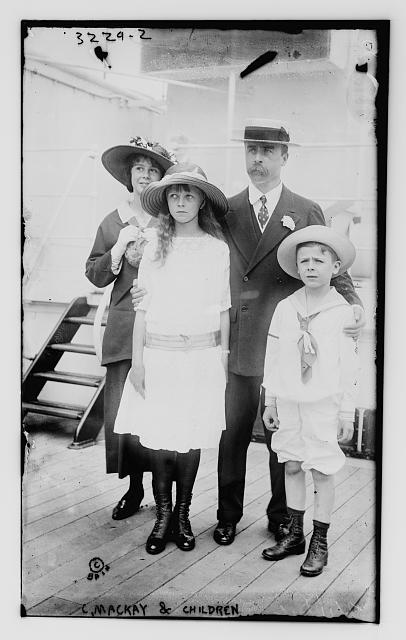

Young boys, too, looked less like little adults. Sailor suits, like the ones worn by the two boys in the background of the fashion plate and by the Mackay boy (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3), and knee-length trousers were popular options. Stretchy, knitted fabrics were popular for boys – and girls – as they were comfortable, allowed for greater freedom of movement, and were easy to make. Both Carnegy brother and sister wear knitted sweaters in 1916 (Fig. 2). By the 1910s, many schools had uniforms for boys consisting of a flannel blazer and shorts (for younger boys) and trousers (for older boys). The young man below has graduated onto trousers, but wears a flannel blazer and tie (Fig. 4). This uniform, or something similar, was often worn outside of school, as well. Like other aspects of fashion in the 1910s, World War I also had an effect on young boys’ fashion as military elements crept into their attire in the latter half of the decade.

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. C. Mackay & children, between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915. 1 negative : glass; (5 x 7 in or smaller). Washington: Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-17240 (digital file from original negative). Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 4 - Bain News Service. Homer, 1919. 1 negative : glass; (5 x 7 in or smaller). Washington: Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-29053 (digital file from original negative). Source: Library of Congress

References:

- “1910s in Western Fashion.” Wikipedia, May 2, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=1910s_in_Western_fashion&oldid=839336973.

- Armstrong, Simon. “The Trench Coat’s Forgotten WW1 Roots.” BBC News, October 5, 2014. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-29033055.

- “First World War Fashions from the Illustrated London News Archive.” Accessed May 31, 2018. http://www.culture24.org.uk/history-and-heritage/military-history/first-world-war/art502502.

- “History of Fashion 1900 – 1970,” July 11, 2013. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/history-of-fashion-1900-1970/.

- Laver, James, Amy De La Haye, and Andrew Tucker. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. 5th ed. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/966352776.

- Lécallier, Sylvie. “Denise Poiret by Delphi.” Palais Galliera | Musée de la mode de la Ville de Paris. Accessed May 31, 2018. http://www.palaisgalliera.paris.fr/en/work/denise-poiret-delphi.

- Moore, Jess. “Family Photos: What Are They Wearing?,” May 24, 2011. https://blog.findmypast.co.uk/family-photos-what-are-they-wearing-1406240689.html.

- “Poiret: King of Fashion.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed May 31, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2007/poiret.

- Stratford, S. J. “1910 to 1919 Kids’ Fashion.” LoveToKnow. Accessed June 1, 2018. https://childrens-clothing.lovetoknow.com/1910-1919-kids-fashion.

- “What Is a Lounge Suit, Anyway?” Moss Bros. Accessed May 31, 2018. https://us.mossbros.com/inside-pocket/post/what-is-a-lounge-suit-anyway.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1910-1919

Events:

- 1910 – Edward VII died; George V became King of England, Mariano Fortuny patents his pleating and dyeing process, Paul Poiret designs a range of loose-fitting, Oriental-inspired dresses, paving the way for modern dress.

- 1912 – China formed a republic, sinking of the Titanic, Nijinsky danced Afternoon of a Faun.

- 1913 – Armory Art Show, The first modern brassiere is patented by New York socialite, Mary Phelps Jacob. Old fashioned corsets are no longer suitable to wear under new lighter, less formal garments. The tango arrives in most European capitals. Jean Paquin designs gowns to be worn for dancing the tango, which is shown during, “dress parades” at popular “Tango Teas” held in London. Coco Chanel opens a boutique in the French seaside resort, Deauville.

- 1914 – Panama Canal opened, World War I begins, ushering in an era of darker colors and simple cuts. Women take over men’s jobs, accelerating the trend toward practical garments. Burberry is commissioned to adapt army officer’s coats for the trenches. The trench coat is born.

- 1915 – Birth of a Nation by D.W. Griffith, Fashion magazine La Gazette du Bon Ton shows full skirts with hemlines above the ankle. They are called the “war crinoline” by the fashion press, who promote the style as “patriotic” and “practical.”

- 1916 – Margaret Sanger opened birth control clinic.

- 1917 – The U.S. declared war on Germany, Russian Czar overthrown. Invented by Gideon Sundback in 1913 the zipper is finally patented in 1917. It is first used for closing rubber boots in the 1920s.

- 1919 – League of Nations chartered, Hollywood’s United Artists founded.

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Periodicals (Digitized)

Filmography

Secondary Sources

Also see the 20th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.

Online

Books/Articles