OVERVIEW

The French Revolution was the defining event of this decade—politically, socially, and culturally. At the meeting of the Estates General in May 1789, dress became a point of contention and between the fall of the Bastille on July 14 to the end of the Reign of Terror in July 1794, men and women’s clothing was the subject of scrutiny, surveillance, and controversy.

Although the Revolution did not introduce new forms of fashionable dress, it strongly influenced attitudes towards clothing and reinforced the trend that emerged in the previous two decades favoring informality and simplicity. In Britain and on the Continent, wools and cottons became more firmly established for men’s daywear and the tailcoat, cut straight across at the waist, replaced the earlier habit and the frock with curved fronts. Women’s dress changed more drastically than men’s during the 1790s. Both white and printed cottons increasingly dominated women’s wardrobes and, by the end of the decade, the columnar white chemise was de rigueur for any woman with pretentions to fashion. In France, the embroidered silks and velvets associated with the Bourbon court would not return until the establishment of the First Empire under Napoleon I in 1804.

Womenswear

Fig. 1 - Maker unknown. Woman's dress (Redingote), ca. 1790. Silk and cotton. Los Angeles: LACMA, M.2009.120. Purchased with funds provided by Robert and Mary M. Looker. Source: LACMA

Fig. 3 - George Romney (British, 1734-1802). Penelope (Rycroft) Lee Acton, 1791. Oil on canvas; (93.75 x 58.25 cm in). Los Angeles: The Huntington, 16.1. Source: The Huntington

Fig. 4 - Maker unknown (French). Jacket, ca. 1790. Silk. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC9113 94-11-2. Source: KCI

Fig. 4 - Rose Adélaïde Ducreux (French, 1761-1802). Self-Portrait with a Harp, 1791. Oil on canvas; 193 x 128.9 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 67.55.1. Bequest of Susan Dwight Bliss, 1966. Source: The Met

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (French). Magasins des Modes Nouvelles, Sept 21, 1789. Paris: Bibliothèque du Mad. Source: Bibliothèque du Mad, Pg. 6

Fig. 6 - A.B. Duhamel after Jean Defraine (French). Magasin des modes Nouvelles, vol. IV, no. 33 (November 11, 1789). Hand-colored etching. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Library. Source: University of Michigan Library

Fig. 7 - Maker unknown (French). Hat (Bicorne), ca. 1790. Wool felt with silk plain weave ribbon cockade. Los Angeles: LACMA, M.2010.33.1. Purchased with funds provided by Michael and Ellen Michelson. Source: LACMA

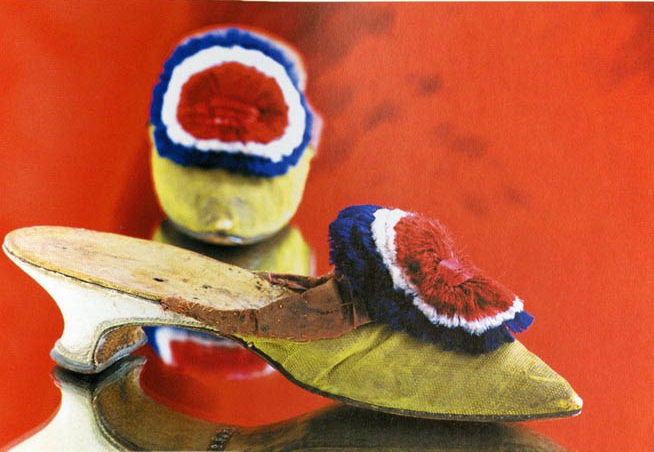

Fig. 8 - Maker unknown (French). Pair of Mules, ca. 1792. Romans: Musée de la Chaussure et d’Ethnologie Regionale. Source: Valence Romans

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown (French). Journal de la Mode et du Goût, 15 April 1790. Etching. Private Collection. Source: Regency Fashion

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown (French). Journal de la Mode et du Goût, 25 August 1790. Etching; 20 x 25.4 cm. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 44.2030. The Elizabeth Day McCormick Collection. Source: MFA Boston

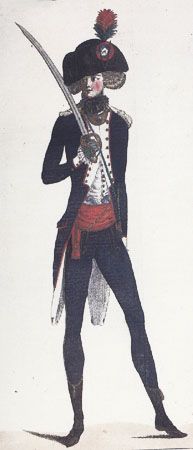

The following year, la mode embraced recent political changes even more enthusiastically. In March, the Journal indicated that women were showing their colors, as it were, by wearing gowns such as the dress à la constitution made of “fine Indian muslin embroidered with tiny, red, white, and blue bouquets” shown in the April 15 issue (Fig. 9 / Ribeiro 58). Women also adopted feminine versions of the red, white, and blue uniform of the National Guard, suitably accessorized with a tricolor cockade and ribbon as seen on a “femme patriote” in the Journal in August 1790 (Fig. 10). The uniform of the National Guard, a citizens’ militia commanded by the Marquis de Lafayette that was set up to keep order during the unrest of mid-July 1789, was “regularized in a decree of 23 July 1790” (Wrigley 64).

In her examination of the Journal, historian Jennifer Jones points to the editor’s reassuring stance towards women’s continued interest in fashion during this tumultuous time that reflected a changing definition of fashion itself in the late eighteenth century by “naturalizing” the relationship between men and women and between women and la mode (Jones 185). During most of the Ancien Régime, a demonstration of luxury (requiring substantial wealth) was the driving force behind one’s self-presentation; however, as the court’s fashion leadership waned in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, taste—a concept that incorporated a wider consumer base—became the guiding principle. Further, “the categories of class, rank, and court etiquette were collapsed onto sex and gender as the primary determinants of fashion” and women’s pursuit of fashion was perceived to be “rooted in their femininity rather than in social etiquette and aristocratic privilege” (Jones 183, 186). In April 1791, a year after the National Assembly had abolished hereditary nobility and the use of aristocratic titles, the Journal informed its elite female readers that, “There only remains, then, for those who wish to play actively and strike the eyes with a lively glitter, the singularity, the richness, and the elegance of one’s costume” (quoted in Jones 186). However, the editor also cautioned women that the “new government does not forbid women to concern themselves with adornment, merely that they combine a certain simplicity with the luxury of the previous times” (quoted in Jones 186). Such “simple” yet “luxurious” costumes were obviously to be found in the pages of the Journal. In November 1792, shortly after the abolition of the monarchy on September 21 and the establishment of a new republican government, the Journal reported that the toilettes of women of distinction conveyed “un air sévère,” perhaps like the ensemble “à l’égalité” (Fig. 11) comprising a matching printed cotton pierrot jacket, skirt and kerchief, worn with a bonnet that was “très à la mode parmi les Républicaines” (very à la mode among Republican women) (quoted in Ribeiro 76-77).

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (French). Journal de la Mode et du Goût, 27th cahier (20 Nov. 1792). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: BGC Visual Media Resources Collection

Fig. 12 - Jean-Baptiste Lesueur (French, 1749-1826). Club Patriotique de Femmes, 1789-1795. Gouache. Paris: Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris, D.9092. Source: Paris Musées

Not all citizens supported the Revolution and some expressed their reservations through their clothing. In April 1790, the Journal de la Mode et du Goût “noted the custom of some ‘aristocrates décidés’ (confirmed aristocrats) to wear full mourning as a sign of their total sympathy with royalty” (Ribeiro 53). And, in February 1792, the editor illustrated a catholic costume (“un costume… catholique”) that demonstrated support for “the clergy who had refused to take an oath of loyalty to the constitution,” decreed in January 1791 (Ribeiro 58). The ensemble consisted of “a red and black pierrot jacket, a white linen skirt… and a bonnet of black trimmed with gold, pearls, diamonds, and an aigrette of white feathers” (Ribeiro 58). However, most of the plates in this periodical between July 1789 and when it ceased publication in 1793 depict fashions that are either nonpolitical or, on the surface, at least, sympathetic to the revolutionary cause.

David’s 1795 portrait of Madame Emilie Sériziat and her son (Fig. 13) illustrates the fashionable female silhouette at the beginning of the Directory (1795-99) following the downfall of Maximilien de Robespierre in June 1794 as well as the changes in the white cotton chemise dress from its introduction in the early 1780s. Rather than the fullness of that decade, Madame Sériziat’s more close-fitting dress has a wide rounded drawstring neckline and gathered bodice, slightly raised waistline accented with a green silk sash, long sleeves buttoned at the wrist, and a softly gathered skirt. The dress has a bib-like opening that fastens at the top of the shoulders and she has tucked a plain white fichu into the front of the bodice. Over her shift (also known as a “chemise” in French), she may be wearing one of the new unboned, high-waisted cotton corsets, although it is possible that the linen bodice lining (seen in many surviving dresses) serves as a bust support (Figs. 14, 15). She also wears a lace-edged cap and a straw hat decorated with a wide silk ribbon and bows matching her sash, tied under her chin with blue ribbons, and her unpowdered, simply styled curly hair reaches her shoulders. Just visible behind the bow on the left side of the hat is the tricolor cockade that was obligatory for women from September 21, 1793 and was still required during the Directory (Ribeiro 77). Since the 1760s, children of both sexes were dressed in short-sleeved white cotton gowns (rather than as miniature versions of their parents) and by the end of the century, portraits and fashion plates show the close similarity between garments worn by adult women and their offspring.

Although English women had been aware of—and often followed—French trends throughout the eighteenth century, this communication was interrupted by the wars between England and France that began in 1793 and, with only a brief cessation of hostilities during the Peace of Amiens in 1802-1803, continued until 1815 when Napoleon was finally defeated at Waterloo. A year after the Journal de la Mode et du Goût ceased publication, Nicolaus Heideloff introduced his high-end fashion magazine, The Gallery of Fashion (1794-1803). Born in Stuttgart, Heideloff lived in Paris during the early years of his career and, at the outbreak of the French Revolution, he went to London where he spent the next three decades (Metropolitan Museum of Art). While women’s dress in England showed the same shift towards one-piece gowns with high waists in the 1790s, the overall silhouette was considerably fuller than in France. The large-format plates of The Gallery of Fashion illustrate the differences—especially evident at the end of the century—between the rounder shape with more coverage preferred by English women than the revealing dresses of their French counterparts (Figs. 16-18).

Fig. 13 - Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825). Madame Pierre Sériziat, née Émilie Pecoul, sister of Mme David, née Marguerite-Charlotte Pécoul, and one of her sons, Émile, born in 1793., 1795. Oil on wood; 131 x 96 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, RF 1282. Source: Louvre

Fig. 14 - Mills Junr. (English). Corset, ca. 1795. Cotton, silk. Providence: RISD Museum, 1987.092. Source: RISD Museum

Fig. 15 - Mills Junr. (English). Corset, ca. 1795. Cotton, silk. Providence: RISD Museum, 1987.092. Source: RISD Museum

Fig. 16 - Nicolaus Heideloff (German, 1761-1837). Gallery of Fashion, vol. 1 (April 1794- March 1795). Etching and engraving. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 50.611. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1950. Source: The Met

Fig. 17 - Nicolaus Heideloff (German, 1761-1837). Gallery of Fashion, vol. 3 (April 1796- March 1797). Etching and engraving. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 50.611.1(3). The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1950. Source: The Met

Fig. 18 - Maker unknown (British). Dress, ca. 1795. Cotton. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1983.156. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn and Alice L. Crowley Bequests, 1983. Source: The Met

Fig. 19 - Maker unknown (English). Trained Gown of Netted Cotton, ca. 1798. Cotton. New York: Cora Ginsburg Collection. Source: Cora Ginsburg Catalog, 2020. Pg. 24-25

Fashion Icon: Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton (1765-1815)

Fig. 1 - George Romney (British, 1734-1802). Lady Hamilton as Nature, 1782. Oil on canvas; 75.9 x 62.9 cm. 1908.1.107. Source: Wikimedia

As curator Quintin Colville asserts, Emma Hamilton’s affair with the celebrated victor of the Battle of the Nile have often defined her and many histories have presented her “principally as a temptress who captured the affections of Britain’s greatest naval hero” and besmirched “the reputation of a man of such unarguable eminence” (Colville 9). Although she was keenly aware of the impact that her beauty had on those around her—especially powerful men—and was “conscious that it acted as her passport,” Emma was not motivated by pure vanity in her social advancement, a charge of which she was frequently accused (Colville 24). And, despite the many ways in which her life was circumscribed by contemporary societal expectations for women (to which she did not necessarily adhere), she “had significant agency and serious intent” (Colville 25).

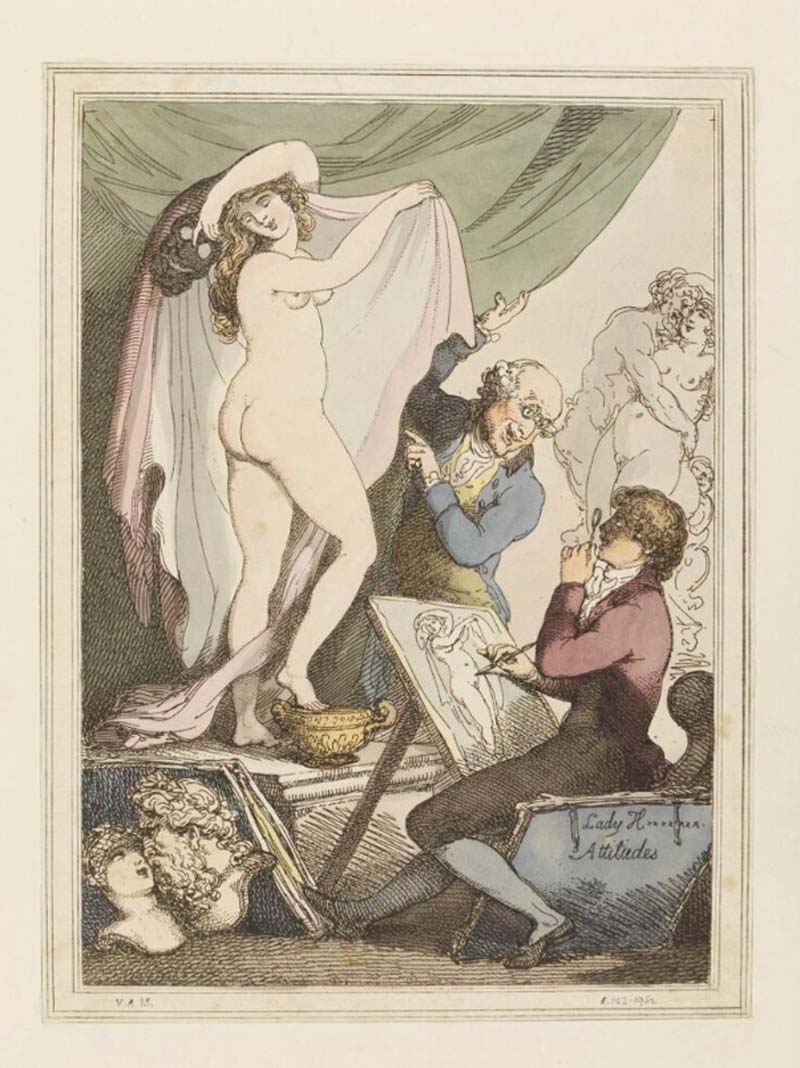

Emma Hamilton’s life was characterized by a series of performances—as a model for leading artists (principally Romney but others including Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun), and, most notably, in her Attitudes that she enacted between about 1786 and 1800 and that brought her widespread acclaim and notoriety (Fig. 4). At the age of 16, Emma Hart (née Amy Lyon), a single mother, became the mistress of Charles Greville, the nephew of Sir William Hamilton, who brought her to Romney’s London studio for the first time in 1782. This young woman who was eager for self-improvement—and willingly submitted to Greville’s tutelage to educate her in the ways and manners of polite society—took advantage of this opportunity, “transforming what could have been a brief engagement into long-standing collaboration and multifaceted artistic education” (Colville 25).

Romney, for his part, was immediately drawn to Emma’s gift for emotional expression and ability to assume theatrical poses that she had learned during a brief stint on the London stage. Over a period of nine years, he would produce over seventy paintings of his “Divine Emma” that range from “society portraits, ‘in character’ representations, rapid ‘unfinished’ sketches… and her portrait incorporated into the subject of history paintings” (Riding 68) (Figs. 5-8). According to curator Christine Riding, “Romney encouraged and nurtured Emma’s talents—which she was to use to such dramatic effect with her famous Attitudes” (Riding 67-68). In his Life of George Romney (1809), the artist’s friend and biographer William Hayley described Emma’s facility for acting:

“Her features, like the language of Shakespeare, could exhibit all the feelings of nature and the gradation of every passion with a most fascinating felicity of expression,” (Riding 63).

Another contemporary, described her as “all Nature, yet all Art” (Seduction and Celebrity 137).

Fig. 2 - Robert Coburn (American, 1900-1990). 'That Hamilton Woman', 1941. Modern bromide print from original negative; 23 x 18 cm. London: National Portrait Gallery, 139689. Given by John Kobal Foundation, 2013. Source: NPG

Fig. 3 - George Romney (British, 1734-1802). Lady Hamilton, 1791. Oil on canvas; 159.1 x 133.1 cm. Austin: Blanton Museum of Art, 1991.108. Bequest of Jack G. Taylor, 1991. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 4 - Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755–1842). Lady Hamilton as a Bacchante, ca. 1790. Oil on canvas; 132.5 x 105.5 cm. Liverpool: National Museums Liverpool, LL 3527. transferred from Lord Leverhulme's private collection, 1922. Source: NML

Fig. 5 - George Romney (British, 1734-1802). Emma Hart, later Lady Hamilton, in a Straw Hat Date, ca. 1782-1784. Oil on canvas; 76.2 x 63.5 cm. San Marino: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, 24.5. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 6 - George Romney (British, 1734-1802). Portrait of Emma Hart, later Lady Hamilton, ca. 1784. Oil on canvas; 74.9 x 61.6 cm. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2019.651. Gift of the heirs of Bettina Looram de Rothschild. Source: MFA

Fig. 7 - George Romney (British, 1734-1802). Emma, Lady Hamilton as a Bacchante, 18th century. Oil on canvas. Private collection, Philip Mould. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 8 - George Romney (British, 1734-1802). Emma Hart, Lady Hamilton, ca. 1782. Oil on canvas; 240.1 x 148.5 cm. Waddesdon: Waddesdon Manor, 104.1995. Loan from Waddesdon (Rothschild Family), 1995. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 9 - Pietro Antonio Novelli (Italian, 1729-1804). The Attitudes of Lady Hamilton, ca. 1791. Pen and brown ink on laid paper; 19.7 x 32.2 cm. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1988.14.1. Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund. Source: NGA

“The Attitudes were important in Emma’s evolution from a London courtesan to an ‘ambassadress,’ and, ultimately political actor in the court of Naples,” (Russell 39).

Further, although Emma was “was known primarily for her visual image” by the mid-1780s, the Attitudes allowed her to exploit the “aura of her ‘real’ presence, forging a connection or ‘touch’ with the viewer” (Russell 146).

On his visit to Naples in 1787, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe saw Emma perform her Attitudes and his description indicates that she had, by then, already developed the elements of these highly individualized presentations. According to Goethe, Sir William:

“has had a Greek costume made for her [Emma] which becomes her extremely. Dressed in this, she lets down her hair and, with a few shawls, gives so much variety to her poses, gestures, expressions, etc. that the spectator can barely believe his eyes. He sees what thousands of artists would have liked to express realized before him in movements and surprising transformations—standing, kneeling, sitting, reclining, serious, sad, playful, ecstatic, contrite, alluring, threatening, anxious, one pose follows another without a break,” (Russell 147).

Although others who saw Emma’s Attitudes were similarly impressed by her emotionally charged evocations of classical and historical figures:

“spectators repeatedly distinguished between the identity of the performer and the success or beauty of the performance” (Bolton 145).

The Comtesse de Boigne, who, as a child in 1792, had participated in the Attitudes, later acknowledged Emma’s dramatic abilities but summarily dismissed the woman herself:

“She brought the statues of antiquity to life and without servile copying, recalled them to the poetic imaginations of the Italians by a sort of improvisation in action. Others have sought to imitate the talent of Lady Hamilton; I don’t believe any have succeeded… Outside this instinct for the arts, nothing was more vulgar and common than Lady Hamilton. After she had shed the antique costume to wear ordinary clothes, she lost all distinction,” (Bolton 145).

Notwithstanding their disdain for Emma Hamilton’s “vulgarity,” her Attitudes, performed for private audiences at Sir William’s residence, became a draw for foreigners on the Grand Tour and other elite visitors to Naples (Russell 155).

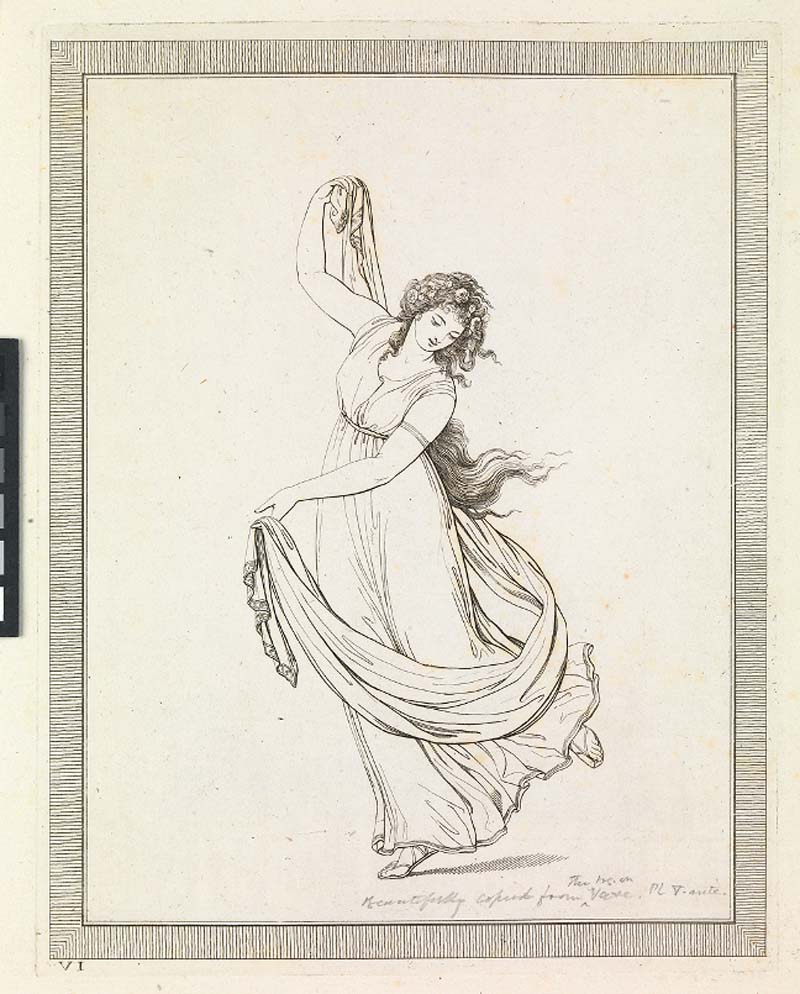

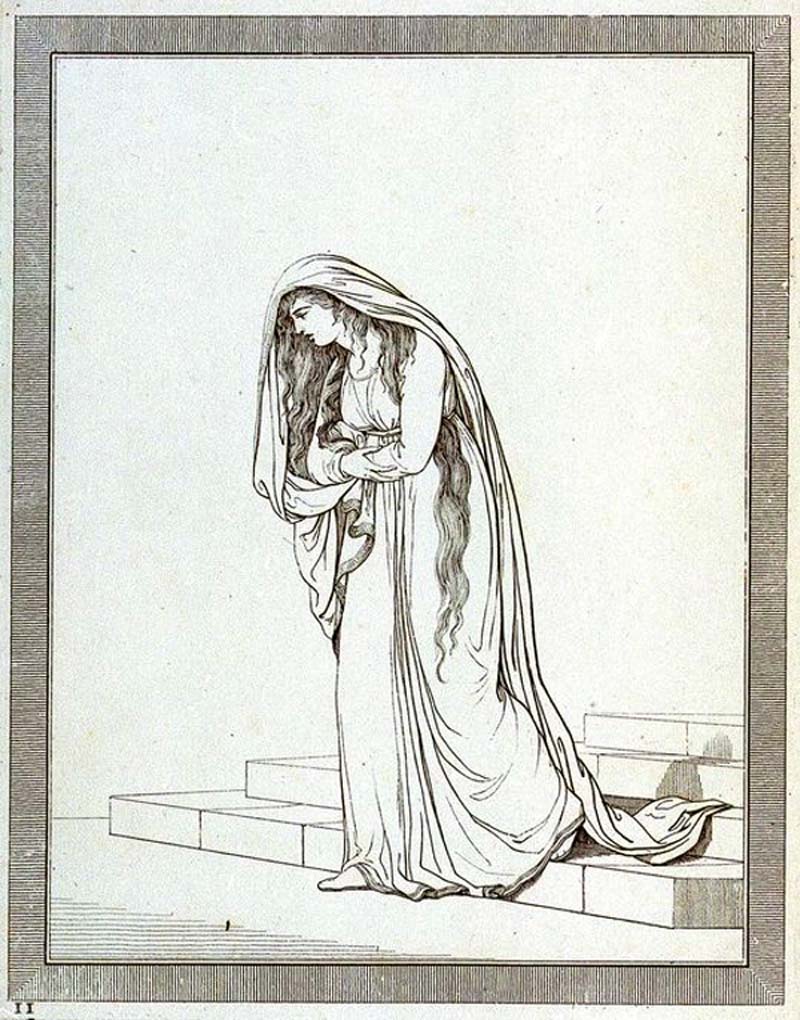

In 1794, the German artist Friedrich Rehlberg published Drawings Faithfully Copied from Nature at Naples that featured twelve of Lady Hamilton’s much larger repertoire of Attitudes, including a Sibyl, the Muse of Dance, Niobe, and Mary Magdalene (Figs. 10, 11). Three years later, an English translation was published in London under the title Lady Hamilton’s Attitudes, an event excitedly reported in The Morning Post: “Lady Hamilton’s attitudes are at last made public” (quoted in Russell 154). Rehlberg’s drawings illustrate the importance of shawls and Emma’s skillful deployment of them. Although Indian shawls would become the rage as fashion accessories by the mid-to-late 1790s, Emma incorporated them as props from 1787, as Goethe attested:

“She knows how to arrange the folds of her veil to match each mood, and has a hundred ways of turning it into a headdress… [A]s a performance, it’s like nothing you ever saw before in your life,” (Bolton 143).

In 1800, the last year that Emma would perform her Attitudes, the Irish writer Melisina Trench highlighted Emma’s use of “several Indian shawls” in enacting different roles and personae:

“She disposes the shawls so as to form Grecian, Turkish, and other drapery, as well as a variety of turbans. Her arrangement of the turbans is absolute sleight-of-hand, and she does it so quickly, so easily, and so well,” (Russell 147).

Following Sir William’s death in 1803, Emma’s financial situation became precarious and when Nelson, her last protector, was killed at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, it declined further. Without the intervention of these influential men who could shield her from public disgrace, Emma was increasingly ostracized by London society. Destitute, Lady Hamilton died in Calais on January 15, 1815, attended by fourteen-year-old Horatia. Although Emma has often been judged harshly by successive generations since the early nineteenth century, her biographer Kate Williams asserts that:

“[Emma’s] early self-representations retained their impact: the Attitudes, the poses, the allure—and, most of all, the sheer power of her skillfully variable self-creation.” (247)

Fig. 10 - Frederick Rehberg (German, 1758-1835). Emma, Lady Hamilton, in a Classical Pose, 1794. Engraving; 23 x 30 cm. London: Royal Museums Greenwich, PAD3221. Source: RMG

Fig. 11 - Friedrich Rehberg (German, 1758-1835). Lady Hamilton II, ca. 1794. Etching; 32.5 x 26 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970.613.25. Purchase, Florance Waterbury Bequest, 1970. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 12 - Johann Heinrich Schmidt (German, 1749-1829). Emma, Lady Hamilton, 1800. Pastel on paper; 46.3 x 39.5 cm. London: Royal Museums Greenwich, PAJ3940. Source: RMG

Fig. 13 - Johann Heinrich Schmidt (German, 1749-1829). Horatio Nelson (1758 -1805), Vice Admiral of the White, 1800. Pastel on paper; 46 x 39.3 cm. London: Royal Museums Greenwich, PAJ3939. Source: RMG

Fig. 14 - Thomas Rowlandson (British, 1756-1827). Lady H Attitudes, ca. 1810s. Etching with aquatint; 23.7 x 17 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, E.122-1952. Given by Michael Sadleur. Source: V&A

Menswear

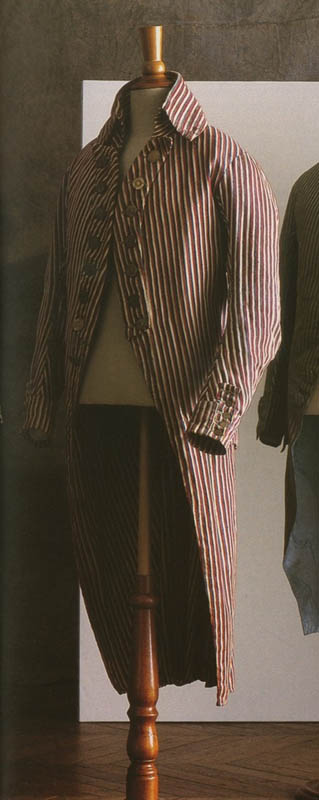

Like women’s dress, men’s daywear fashions of the early 1790s were similar to those of the preceding decade. Three-piece suits comprising single- or double-breasted coats with standing or turned-down collars (the latter known as a frock, or fraque) fitted closely to the body with long tight sleeves and cutaway fronts, single- or double-breasted waistcoats cut straight across, and slim breeches were in vogue. In addition to solid-colored often dark wools, striped silks were popular for men as well as women (Figs. 1, 2).

In France, after July 1789, the Magasin des Modes nouvelles discussed the impact of the political upheaval on men’s dress. Although the forms of their suits remained the same, colors took on new meanings, as was the case with women’s clothing. A striped tricolor cotton coat in the collection of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Fig. 3) was presumably worn by a firm supporter of the Revolution, and the national cockade that appeared on women’s headwear was also worn by men. In October 1789, the Magasin des Modes nouvelles insisted that “The national cockade… is worn, or should be, by absolutely all the men of the capital who can be called to bear arms”—that is, those who were eligible to join the National Guard (Fig. 4 / quoted in Chrisman-Campbell 273). The cockade was obligatory for all men following a decree of July 5, 1792 (Hunt 59). A plate from April 1790 (Fig. 5) shows a “demi-converti” (half-converted) in a red coat, black waistcoat, breeches, stockings, hat and buckled shoes. This young no longer titled aristocrat is beginning to accustom himself to the new constitution, although he is not fully in favor of the current changes (Ribeiro 54). The text accompanying the plate describes his ensemble as “half-mourning,” referring to the aristocrats who lamented “the diminished powers of the monarchy and [signaled] their willingness to die for the royal cause” (Ribeiro 53-54).

Fig. 1 - Maker unknown (French). Coat and Vest, 1790-1795. Los Angeles: LACMA. Source: LACMA

Fig. 2 - French. Ensemble, ca. 1790. Silk, cotton. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2010.33.1. Purchased with funds provided by Michael and Ellen Michelson. Source: LACMA

Fig. 3 - Maker unknown (French). Man's Coat, 1789-1791. Paris: Musée de la Mode et du Textile, UF 55-75-1. Source: MAD

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Journal de la mode et de gout, no. 7 (April 25, 1790): Plate 1. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (French). Journal de la Mode et du Goût, 15 April 1790. Etching. Private Collection. Source: Regency Fashion

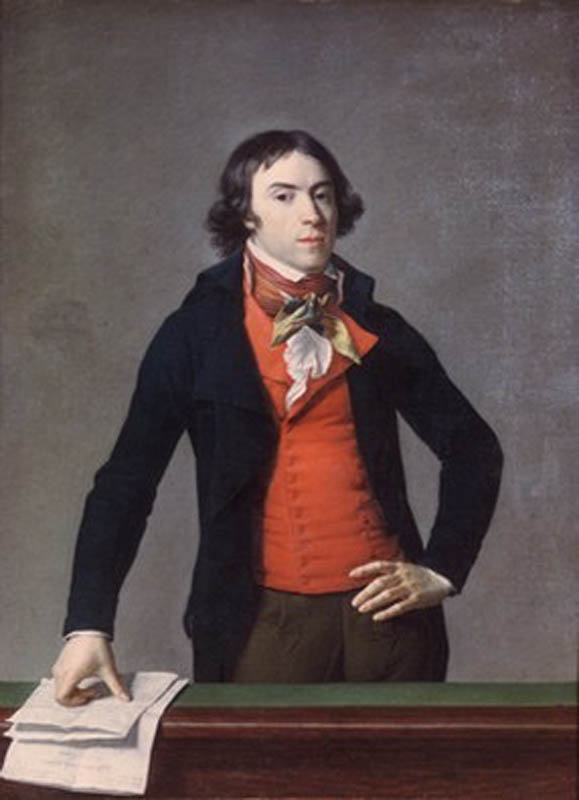

The politically correct simplicity of male dress during the Revolution is evident in Jean-Louis Laneuville’s 1793-94 portrait of Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac (Fig. 8), a member of the National Convention and the Committee of Public Safety that ruled France during the Terror, and exemplifies the revolutionaries’ belief that “dress revealed something about the person” (Hunt 82). His tailcoat with a high turned-down collar and wide lapels, double-breasted waistcoat with lapels, and fall-front breeches are all made of solid-colored wools; his white linen shirt has a fashionably high collar with its top edges just visible over his checked cotton cravat and a plain frill; and his hair is unpowdered. The folded papers under his right hand refer to the trial and sentencing of “Louis Capet” (a dismissive reference to the king’s dynastic lineage) that took place in January 1793. As art historian Amy Freund notes, Laneuville’s portrait of Barère is typical of the artist’s style during the Revolutionary years and “the illusion of immediacy and transparency fostered by these visual strategies suited Revolutionary notions of the politically engaged self” (Freund 332).

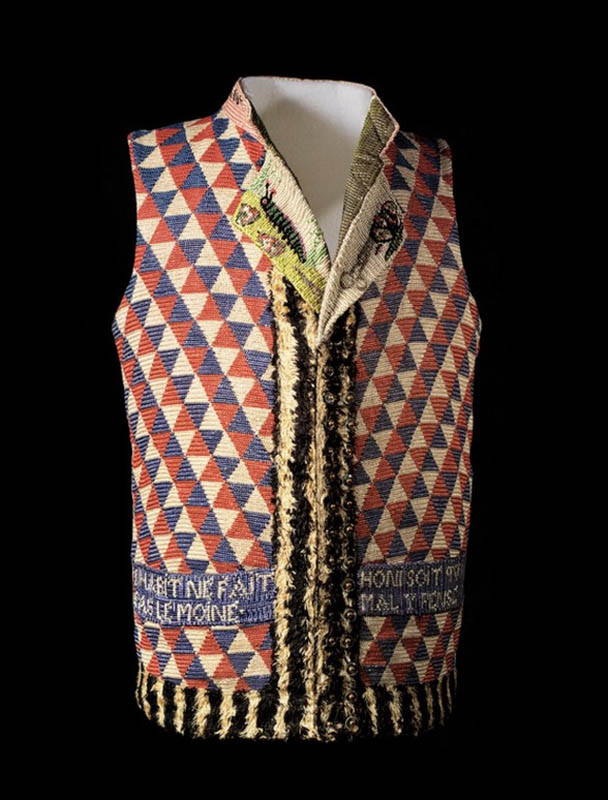

Fig. 6 - Maker unknown (French). Vest, 1789-1794. Linen canvas with silk needlepoint. Los Angeles: LACMA, M.2007.211.1078. Purchased with funds provided by Suzanne A. Saperstein and Michael and Ellen Michelson, with additional funding from the Costume Council, the Edgerton Foundation, Gail and Gerald Oppenheimer, Maureen H. Shapiro, Grace Tsao, and Lenore and Richard Wayne. Source: LACMA

Fig. 7 - Maker unknown (French). Vest, 1789-1794. Linen canvas with silk needlepoint. Los Angeles: LACMA, M.2007.211.1078. Purchased with funds provided by Suzanne A. Saperstein and Michael and Ellen Michelson, with additional funding from the Costume Council, the Edgerton Foundation, Gail and Gerald Oppenheimer, Maureen H. Shapiro, Grace Tsao, and Lenore and Richard Wayne. Source: LACMA

Fig. 8 - Jean-Louis Laneuville (French). Portrait of Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac, 1793-1794. Oil on canvas; 130 x 97 cm. Munich: Neue Pinakothek. Source: Wikimedia Commons

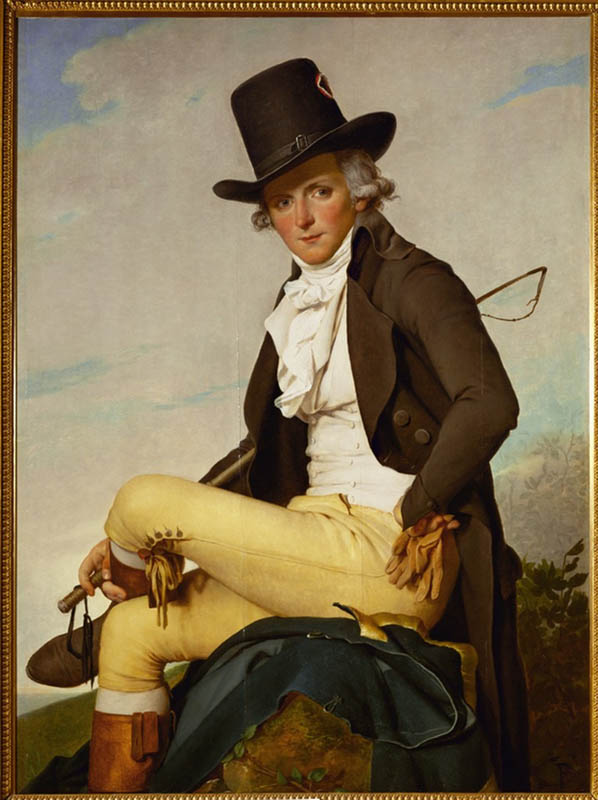

Fig. 9 - Jacques-Louis France David (French, 1748-1825). Pierre Sériziat (1757-1847), brother-in-law of the artist., 1795. Oil on wood; 129 x 96 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, RF 1281. Source: Louvre

Fig. 10 - Louis-Léopold Boilly (French). Presumed portrait of Robespierre, ca. 1791. Oil on canvas; 41 x 32.5 cm. Lille: Palais Beaux-Arts Lille. Source: PBA

More stylish than the austere Barère is Pierre Sériziat in his 1795 portrait by David (Fig. 9), pendant to the artist’s depiction of his wife Emilie Sériziat (Fig. 13 in womenswear). His Anglo-inflected ensemble includes a “jockey” hat (accessorized with the requisite national cockade), English-style riding boots, and a whip. He also wears a brown wool double-breasted coat with a high turned-down collar and wide lapels, double-breasted white waistcoat, long close-fitting buckskin breeches (David has painted the small creases under his right knee) with a fall front and ties at the knee, and white silk stockings. His hair is lightly powdered and his immaculate white linen shirt, tied with a matching cravat, has a deep frill. He carries a pair of leather gloves and next to him on the rock is his greatcoat with a gold-edged collar.

In contrast to Barère’s understated, almost severe, appearance, Maximilien de Robespierre (Fig. 10), a member of the radical Jacobin Club, the Paris Commune, and the Committee of Public Safety and one of most powerful men in France between 1792 and 1794, was known for his adherence to Ancien régime dress. In his portrait by Louis-Léopold Boilly, Robespierre’s powdered wig, silk habit, frilled shirt, and breeches fastened with jeweled buckles would seem to be those of a royalist sympathizer than the ruthless revolutionary who was known as “The Incorruptible” for his unswerving commitment to the Revolution (Fig. 10). And, in fact, it was this devotion to the cause that excused Robespierre’s showy dress since he was perceived as a bridge between the politically empowered bourgeois deputies and the ardently anti-monarchical unenfranchised classes.

Fig. 11 - Pierre Étienne Lesueur (French). Jacobin Knitters, ca. 1790-1793. Paris: Musée Carnavalet. Source: Flickr

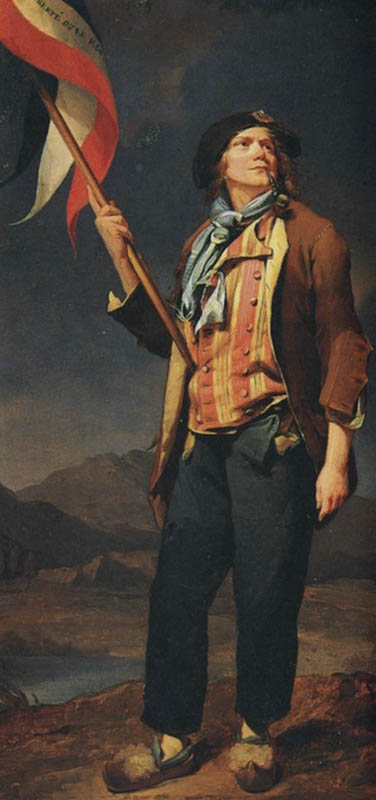

Fig. 12 - Louis Léopold Boilly (French, 1761-1845). Portrait du chanteur Simon Chenard (1758-1832), en costume de sans-culotte, porte-drapeau lors de la fête en l'honneur de la liberté de la Savoie, le 14 octobre 1792, ca. 1792. Oil on wood; 33.5 x 25.4 cm. Paris: Musée Histoire De Paris Carnavalet, P8. Source: Musée Histoire De Paris Carnavalet

Fig. 13 - Maker unknown (French). Sans-culottes ensemble, ca. 1790. Cotton plain weave. Los Angeles: LACMA, M.2010.205. Purchased with funds provided by Phillip Lim. Source: LACMA

Fig. 14 - Jacques-Louise David (French, 1748-1825). Self Portrait, 1794. Oil on canvas; 81 x 64 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, INV 3705. Source: Wikimedia Commons

“two contradictory principles… On the one hand, the deputies of representatives of the people were supposed to be… just like them, because part of them… On the other hand, the representatives were obviously other, different, not like the people exactly because they were the teachers, the governors, the guides of the people.” (Hunt 77)

After the downfall of Robespierre, the issue of civilian dress disappeared, but that of official costume still concerned legislators and, in November 1797, the government of the Directory agreed on a costume that was to be worn by all deputies comprising “a ‘French’ coat of ‘national blue,’ a tricolor belt, a scarlet cloak à la grecque, and a velvet hat with tricolor aigrette” (Hunt 77, 79). When this uniform was finally adopted in February 1798, the response was unenthusiastic. The editor of the Moniteur found that “this great quantity of red clothing fatigues the eyes extremely; yet it must be admitted that this costume has in it something beautiful, imposing and truly senatorial” (quoted in Hunt 80). Bouquerot de Voligny (Fig. 17), a member of the Council of Ancients (one of the governing bodies of the Directory), proudly sat for his portrait in the full splendor of this decidedly distinctive official costume with its “quite noble and picturesque” elements as well as its “theatrical air” that were remarked on by a foreign visitor to Paris (Fig. 18 / quoted in Hunt 80).

Fig. 15 - Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825). Civic Costume Project – Habit of a French Citizen, 1794. Paris: RMN-Grand Palais. Source: L'Histoire par L'Image

Fig. 16 - Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825). Civic Costume Project – Habit of a Legislator, 1794. Paris: RMN-Grand Palais. Source: L'Histoire par L'Image

Fig. 17 - Artist unknown (French). Thomas André Marie Bouquerot de Voligny (1755-1841), député de la Nièvre au Conseil des Anciens, portrait en grand uniforme de membre du Conseil des Anciens, ca. 1798-1799. Oil on canvas. Vizille: Musée de la Révolution Française. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 18 - Maker unknown (French). 'The People's Representative' Coat, ca. 1798. Wool. Paris: Palais Galliera, GAL 1972.26.1. Source: Palais Galliera

DRESS DURING THE DIRECTORY (1795-1799)

Fig. 2 - Maker unknown (British). Pair of Shoes, 1790s. Leather. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.481&A-1913. Source: V&A

Fig. 1 - Alexis Chataignier (French, 1772-1817). Ah! Quelle antiquité!!!, 1797. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, ark:/12148/btv1b84127842. Source: BNF Gallica

“with their square-cut coats and their hounds’ ears locks of hair. Just imagine—they wore medallions, lorgnettes, chains, ear-rings, cameos, and had their cadenenttes [the hair looped up at the back] caught up with a comb. They had the most ridiculous stockings you have ever seen, for they were striped across so as to make large coloured rings round their legs. They also surrounded their necks with an extraordinary style of cravat.” (Fig. 4 / quoted in Waugh/Men 109-110)

Fig. 3 - Louis Darcis (French). Satirical print, 1796. Stipple printed in color; 30.6 x 35.5 cm. London: The British Museum, 1874,0711.835. Source: The British Museum

Fig. 4 - Maker unknown (French). Coat, 1790s. Silk and cotton. Los Angeles: LACMA, M.2007.211.802. Purchased with funds provided by Suzanne A. Saperstein and Michael and Ellen Michelson, with additional funding from the Costume Council, the Edgerton Foundation, Gail and Gerald Oppenheimer, Maureen H. Shapiro, Grace Tsao, and Lenore and Richard Wayne. Source: LACMA

Fig. 5 - Louis-Léopold Boilly (French, 1761-1845). The Incredible March, ca. 1797. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Source: La Tribune de l'Art

The four years of the Directory have been characterized as a period of social flux, headiness, venality, and corruption. After the political repression and guillotining of thousands of men and women throughout France during the Reign of Terror, Parisians reacted by engaging in a flamboyant lifestyle and a full-on return to the pursuit of fashion. Art historian Susan Siegfried’s examination of the works of Louis-Léopold Boilly reveals his (and the wider contemporary) fascination with the different urban types seen on the streets of Paris and the jostling for power among the nouveaux riches, former nobles, and returning émigrés (Fig. 5). Although the Tableau Général du Goût, des Modes et Costumes de Paris that appeared in 1797, signaling a return of the fashion press, claimed that manners and attention to dress were once again acceptable for polite society, critics like Louis-Sébastien Mercier, visitors to Paris, and caricatures commented on men’s slovenly appearance, the scantiness of women’s attire, and the dissipation on view at both private and public gatherings (Figs. 6, 7).

Fig. 6 - Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauvuer (French, 1757-1810). Costumes de Différent Pays, 'Français et Françaises.', ca. 1797. Hand-tinted engraving on paper; 26.3 x 18.3 cm. Los Angeles: LACMA, Inv. Nr. M. 83.190.2. Source: AKG Images

Fig. 7 - Jean François Bosio (French, 1764-1827). La Bouillotte, 1804. Engraving; 42.7 x 54.9 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, RP-P-OB-103.747. Source: Rijksmuseum

“[There were] scintillating parties at which the whole splendor of Greek and Roman fashion was revealed to perfection. How little resemblance there is between this Paris under its new administration and that of the Revolution! Balls, spectacles, and fireworks have replaced prisons and revolutionary committees… The court ladies have disappeared; the newly rich have taken their place and are surrounded… by courtesans who compete with them in extravagance and extreme fashion. These sirens are surrounded in turn by a swarm of fools, who used to be called petits-maîtres and are now known as merveilleux. They talk of politics as they dance, and express their longing for the return of the monarchy as they eat ices or watch fireworks with affected boredom.” (quoted in Willms 94)

Demeunier’s assessment of the transformation of Parisian society and its post-Thermidorean lifestyle (Fig. 8) is one of many similar responses to those who lived in or visited the French capital.

Fig. 9 - Jean-Baptiste-François Desoria (French, 1758-1832). Portrait of Constance Pipelet, 1797. Oil on canvas; 130 x 99.1 cm. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1939.533. Simeon B. Williams Fund. Source: Art Institute of Chicago

Fig. 10 - Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825). Portrait of Madame de Verninac, 1799. Oil paint; 145.5 x 112 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, RF 1942-16. Donations Carlos de Beistegui, princesse Louis de Croÿ, Hélène et Victor Lyon. Source: Wikimedia Commons

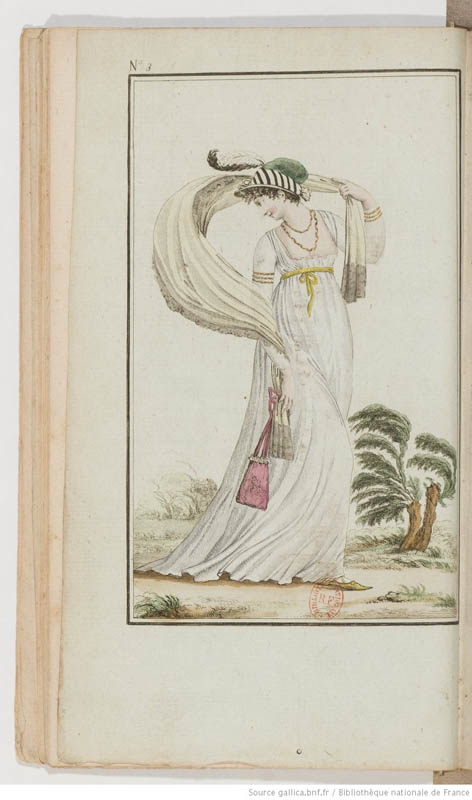

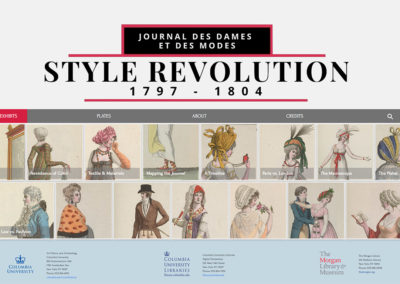

In 1798, the Journal des Dames et des Modes (1797-1839) that would become the most influential French fashion periodical of the early nineteenth century illustrated a sleeveless dress, dubbed “à la prêtresse” worn with knitted silk sleeves. The text accompanying a 1798 plate in the Tableau Général du Goût shows a sleeveless chemise with knitted “flesh-colored” sleeves that were reportedly relegated to theatre corridors (Fig. 12); the few women who preferred knitted sleeves to “nudity” wore white ones. Josephine du Pont who emigrated to the United States with her husband Victor Marie du Pont in 1795 was back in France in 1798, from where she wrote to Margaret Manigault, her friend in Charleston, often describing the latest fashions in detail. In Paris in December, she reported that “The women who do not leave their arms bare resort to silk sleeves held in place by very small fichus [bands]” (quoted in Low 46). She also commented on the body-revealing aspect of chemises and the ideal physique needed to appear alluring:

“Rounded figures are required; the women eat heavily to fatten themselves. You can imagine how attractive one must be to stand a dress without a single bit of lace around it, although one can keep from looking indecent by the way it is made.” (quoted in Low 46)

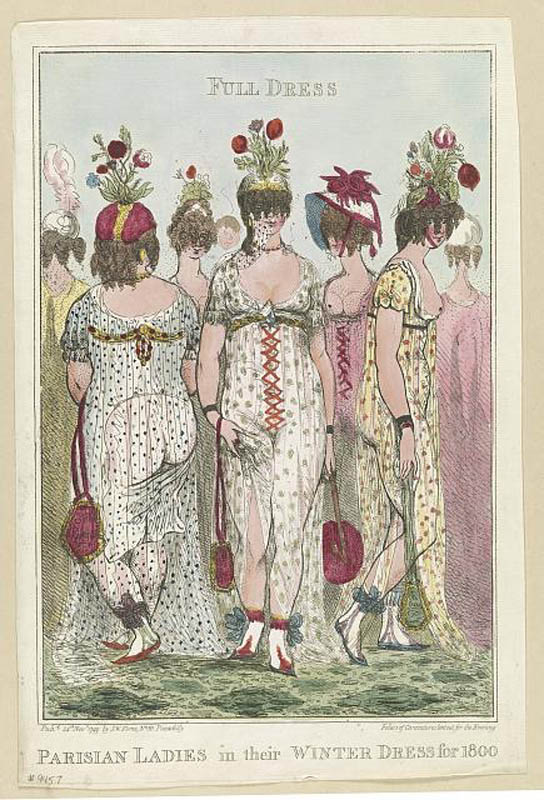

Many caricatures from the turn of the nineteenth century satirize not only the sheerness of muslin gowns but less-than-suitable female bodies that are excessively thin or fat.

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (Indian). Shawl, 1800-1820. Wool, silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.39.13.36. Gift of Mr. Lee Simonson, 1939. Source: The Met

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown (French). Tableau général du goût, des modes et costumes de Paris, October 1798. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 12148/ bpt6k311724g. Source: BNF Gallica

A young unidentified woman (also seated on a understated chair and accessorized with a shawl) painted by a follower of David around 1798 (Fig. 13) displays the most exaggerated version of neoclassical dress evoked by Louis-Sébastien Mercier in his description of public balls a few years earlier:

“Here lighted lustres reflect their splendour on beauties dressed à la Cléopatre, à la Diane, à la Psyché; there, a smoky lamp sheds its oily beams on a troop of washerwomen who dance in wooden shoes, with their muscadins, to the noise of some sorry scraper. I know not whether these dancers have any great affection for the republican forms of the Grecian governments, but they have modelled the form of their dress after that of Aspasia [fifth century BC Greek courtesan and mistress of Pericles]; bare arms, naked breasts, feet shod with sandals, their hair turned in tresses around their heads by modish hairdressers, who study the antique busts. Guess where are the pockets of these dancers? They have none; they stick their fan in their belt, and lodge in their bosom a slight purse of morocco leather in which are a few spare guineas. As to the ignoble handkerchief, it is in the pocket of some courtier, to whom they address themselves in case of need. The shift has long been banished, as it seemed only to spoil the contours of nature; and besides it was an inconvenient part of dress… The flesh-coloured knit-work silk stays, which stuck close to the body did not leave the beholder to divine, but perceive every secret charm. This is what was being called being dressed à la sauvage, and the women dressed in this manner during a rigorous winter, in spite of frost and snow.” (quoted in Ribeiro 124, 127)

An English satirical print, entitled “Parisian Ladies in their Winter Dress for 1800,” (Fig. 14) illustrates a group of women whose faces are almost entirely concealed by their drooping curls but whose individual shapes are fully visible through their transparent gowns.

Fig. 13 - Circle of Jacques-Louis David (French). Portrait of a Young Women in White, ca. 1798. Oil on canvas; 125.5 x 95 cm. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1963.10.118. Chester Dale Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 14 - Artist unknown (British). Parisian Ladies in their winter dress for 1800, 1799. Engraving; 39 x 36 cm. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, PC 1 - 9457 (A size) [P&P]. Source: LOC

Fig. 15 - Artist unknown (French). Fashion Plate Showing a Woman in Empire Period dress and Jewelry, ca. 1800. Paris: Musée de la Mode and du Costume. Source: Artstor

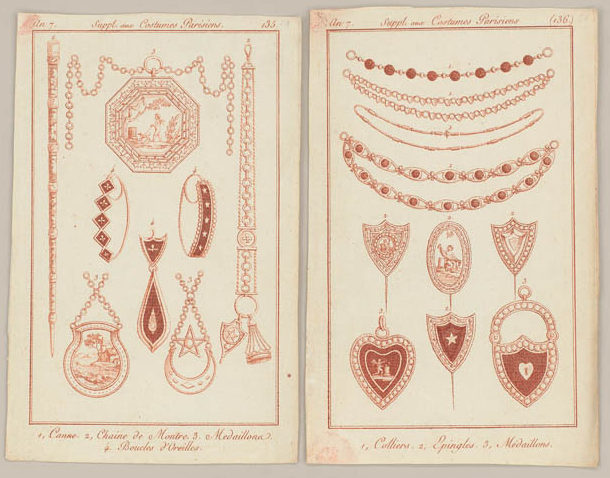

Fig. 16 - Artist unknown (French). Journal des dames et des modes, 1799, plates 135-136. New York: The Morgan Library & Museum. Source: Style Revolution: Journal des dames et des modes

Fig. 17 - Artist unknown (French). Journal des Dames et des Modes, 1798-1700. Source: KDD & Co

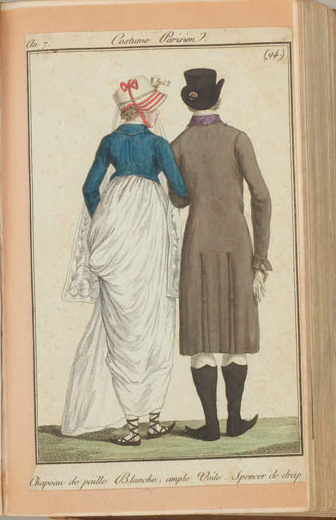

Fig. 18 - Artist unknown (French). Journal des dames et des modes, plate 94 (20 Feb. 1798). New York: The Morgan Library & Museum. Source: Style Revolution: Journal des dames et des modes

New forms of jewelry were also introduced in the late eighteenth century to compliment the overall simplicity of neoclassical dress. Like fashionable hats, shoes, and shawls, jewelry expressed the wearer’s personal taste and her wealth (Figs. 15, 16). Combs and bandeaux decorated long or short hair, bracelets were worn not only at the wrist as previously but now adorned the upper arm, and necklaces included a variety of chokers and long chain necklaces. Two 1799 plates from the Journal des Dames et des Modes illustrate short necklaces, hoop earrings, medallions, and hair pins. The extensive use of “cameos, engraved gems, and semi-precious stones like turquoise” reflected the vogue for classical antiquity that was at its height around 1800 (Ribeiro 132).

Perhaps one of the most striking changes for women at the turn of the nineteenth century was the rage for short hair and short-haired wigs (Figs. 9, 12, 15, 17 / Ribeiro 132). Upon her arrival in Bordeaux in July, Josephine du Pont compared herself to the “merveilleuses” with her blond wig, hat or bonnet, flat shoes, and a “robe hiked at the side,” and was not “absolutely displeased with the effect” (quoted in Low 43). From Paris the following month, she reported on the fashion for Titus hairstyles for men (like that worn by her husband) and for women: “this fashion is extremely convenient, especially when we have a wig for the sake of variety” (quoted in Low 45). In December, she once again referred to the “Titus hairdos, or crops [that] are coming into vogue” and the “little blond wigs, which invariably take ten years off the age of the wearer [that] are the most popular” (quoted in Low 45). The young woman “à la promenade” in the Tableau Général du Goût plate (Fig. 12) wears a blonde wig “à la Nayade;” in the accompanying text, the editor reports on women’s current affinity for wigs and indicates that they change the color of their hair every day, just as they change their gowns (37).

In 1799, the Journal des Dames et des Modes illustrated an arm-in-arm couple out for a walk, seemingly on their way into the nineteenth century (Fig. 18). Depicted from the back, their slender silhouettes are a long way from the breadth that characterized the fashionable shape for most of the eighteenth century, particularly for women. Attached to the side of the woman’s straw bonnet is a long lace veil, a point of fashion noted by the editor (Journal des Dames et des Modes). Her blue wool “spencer,” as it was known in France, is a type of outerwear recently adopted by women on both sides of the Channel. Named for George Spencer, 2nd Earl of Spencer, whose coattails were reputedly torn off during a hunting accident, this garment provided additional warmth at a time when sheer cotton dresses were worn year-round. The wool fabric and understated tailoring of this spencer reflect the influence of masculine dress, but fashion plates and surviving examples attest to the seasonal use of silks, velvets, and sturdy cottons and, increasingly, applied decoration on the fronts, sleeves, and collar. Although women also began to wear full-length coats in the early nineteenth century, spencers remained in vogue until the mid-to-late 1820s when the high waistline returned to its natural placement. The couple’s flat-soled ribbon-tied shoes and boots share the needle-pointed toes that were at their most exaggerated around 1800.

CHILDREN’S WEAR

(BY SUMMER LEE)

Locke and Rousseau advocated that young children receive more regular hygiene. They also believed that dressing children in many layers of heavy fabrics was bad for their health. For those reasons, linen and cotton fabrics were preferred for babies and very young children because they were lightweight and easily washable (Paoletti).

Although the tradition was in decline, some infants may have been swaddled. Swaddling was a very long-held European tradition where an infant’s limbs are immobilized in tight cloth wrappings (Callahan). The practice was losing popularity due to the opposition of Locke and Rousseau (Paoletti).

Babies were then dressed in “slips” or “long clothes” until they began to crawl (Fig. 1) (Callahan). These were ensembles with very long, full skirts that extended beyond the feet (Nunn 99). Babies also sometimes wore tight-fitting caps on their heads.

Once a child was becoming mobile, they transitioned into “short clothes” (Callahan). Unlike long clothes, these ensembles ended at the ankles, allowing for greater freedom of movement (Callahan). Short gowns had back-opening bodices and sometimes “leading strings” attached at the back or tied under the arms (Magidson). Leading strings were streamers of fabric used to protect young children from falling or wandering off (“Childhood”).

The prevailing fashion for short clothes in the 1790s had emerged in the 1760s: a white frock worn with a colored sash around the waist (Fig. 2). This style was worn by very young children of both sexes. The most common sash colors were pink and blue, although they were not used to indicate gender. A colored underslip may have also been worn, which would show through the translucent white top material (Paoletti). While this style originated with very small children, it quickly became more pervasive: in the 1790s, a very similar style was worn by girls even into their teens. Some portraiture from the later years of the 1790s show young children in a high-waisted white frock dress with no colored sash (see Fig. 3). This style would become the reigning fashion for childrenswear — and womenswear — in the early nineteenth century (Callahan).

A significant development in fashion for young boys occurred in the 1780s. Previously, young boys wore skirted gowns until they were “breeched” by age seven, and then wore adult menswear styles (Reinier). However, boys now wore a transitional type of ensemble for young boys called a “skeleton suit” from approximately ages three to seven (Fig. 2) (Callahan). Skeleton suits “consisted of ankle-length trousers buttoned onto a short jacket worn over a shirt with a wide collar edged in ruffles” (Callahan). Older boys would then wear ensembles resembling adult menswear, although the fit was typically looser and more relaxed (Fig. 4).

An American group portrait titled The Cheney Family, circa 1795, is an excellent visual resource for 1790s children’s wear (Fig. 5). The youngest children wear long gowns and short gowns. A young boy wears a skeleton suit while an older boy wears a relaxed variation of a menswear suit. Three girls stand in order of height, each wearing a white frock gown with a pink waist sash.

Fig. 1 - Joseph Wright (English, 1734 -1797). Detail from The Wright Family, 1793. Oil on canvas; 94.8 x 81.3 cm (37 5/16 x 32 in). Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1886.5. Gift of Edward S. Clarke. Source: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Fig. 2 - George Romney (English, 1734-1802). Portrait of the Willett Children, 1789-1791. Oil on canvas; 152.4 × 121.9 cm (60 × 48 in). Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, E1924-4-27. The George W. Elkins Collection, 1924. Source: Philadelphia Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - John Hooner (British, 1758-1810). The Sackville Children, 1786. Oil on canvas; 152.4 x 124.5 cm (60 x 49 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 53.59.3. Bequest of Thomas W. Lamont, 1948. Source: The Met

Fig. 4 - Thomas Beach (English, 1738–1806). William, Mary Ann, and John De la Pole as Children, 1793. Oil on canvas; 228 x 142 cm. Torpoint: National Trust, Antony, 353008. Source: Art UK

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. The Cheney Family, ca. 1795. Oil on canvas; 49 x 65 cm (19 5/16 x 25 9/16 in). Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1958.9.9. Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch. Source: National Gallery of Art

References:

- Bolton, Betsy. “Sensibility and Speculation: Emma Hamilton.” Lewd & Notorious: Female Transgression in the Eighteenth Century. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/587706301.

- Boquillon, Michèle. “Le ‘Portrait parlant’ de Jean-Baptiste Belley.” Nineteenth-Century French Studies Vol. 33, No. 1/2 (Fall-Winter, 2004-2005): 35-56. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/356700565.

- Callahan, Colleen R. “Children’s Clothing.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed August 08, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0003223.

- “Childhood.” In European Renaissance and Reformation, 1350-1600, edited by Norman J. Wilson, 319-321. Vol. 1 of World Eras. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2001. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3034600137/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=480f4328.

- Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly. Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/889941128.

- Colville, Quintin. “Introduction: Re-imagining Emma Hamilton.” In Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity, edited by Quintin Colville with Kate Williams, 8-31. New York: Thames & Hudson Inc; London: In association with the Royal Museums Greenwich, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/994745260.

- Cunnington, C. Willett. Handbook of English Costume in the Eighteenth Century. London: Faber, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/898891338.

- Cunnington, Phillis. The History of Underclothes. New York: Dover Publications, 1992. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868279842.

- DeGregorio, William. “Trained Gown of Netted Cotton, English, ca. 1798.” Cora Ginsburg: A Catalogue of 17th to 19th-century costume textiles & needlework. New York, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/970604231.

- Freund, Amy. “The Citoyenne Tallien: Women, Politics, and Portraiture during the French Revolution.” Art Bulletin, Vol. XCIII No. 3 (September 2002): 325-344. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5570727762.

- Grigsby, Darcy Grimaldo. Extremities: Painting Empire in Post-Revolutionary France. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/6826560444.

- Hunt, Lynn. “Introduction: Re-imagining Emma Hamilton.” In Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity, edited by Quintin Colville with Kate Williams, 8-31. New York: Thames & Hudson Inc; London: In association with the Royal Museums Greenwich, 2016.rnia Press, 1984. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/54001693.

- Jones, Jennifer. Sexing La Mode: Gender, Fashion and Commercial Culture in Old Regime France. Oxford and New York: Berg, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1201426327.

- Kelly, Jason M. “A Classical Education: Naples and the Heart of European Culture.” In Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity, edited by Quintin Colville with Kate Williams, 108-137. New York: Thames & Hudson Inc; London: In association with the Royal Museums Greenwich, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/994745260.

- Levy, Darline Gay, Harriet Branson Applewhite, and Mary Durham Jones. Women in Revolutionary Paris 1789-1795. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/959235281.

- Low, Betty-Bright P. “Of Muslins and Merveilleuses: Excerpts from the Letters of Josephine du Pont and Margaret Manigault.” Winterthur Portfolio Vol. 9 (1974): 29-75. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5548166455.

- Magasins des Modes Nouvelles francaises et anglaises. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10461536s/f7.item.

- Magidson, Phyllis. “Fashion.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 344-348. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3402800166/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=0084684d.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Gallery of Fashion, Vol. I: April 1, 1794- March 1, 1795.” Accessed July 14, 2021. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/837922.

- Nunn, Joan. Fashion in Costume 1200-2000. Bridgewater, NJ: Distributed by Paw Prints/Baker & Taylor, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/232125801

- Paoletti, Jo Barraclough. “Children and Adolescents in the United States.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: The United States and Canada, edited by Phyllis G. Tortora, 208–219. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed August 28, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch3029.

- Reinier, Jacqueline S. “Breeching.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 118. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3402800074/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=360a7a45

- Ribeiro, Aileen. Fashion in the French Revolution. New. York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. 1988. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/925254276.

- Ribeiro, Aileen. The Art of Dress: Fashion in England and France from 1750 to 1820. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/450347616.

- Riding, Christine. “Romney’s Muse: A Creative Partnership in Portraiture.” In Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity, edited by Quintin Colville with Kate Williams, 62-93. New York: Thames & Hudson Inc; London: In association with the Royal Museums Greenwich, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/994745260.

- _______. “Picturing Personas: Emma, George Romney and the Portrait Print.” In Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity, edited by Quintin Colville with Kate Williams, 94-107. New York: Thames & Hudson Inc; London: In association with the Royal Museums Greenwich, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/994745260.

- Rothstein, Natalie. A Lady of Fashion: Barbara Johnson’s Album of Styles and Fabrics. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/748992365.

- Rothstein, Natalie. Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Boston: Little, Brown, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/936909261.

- Russell, Gillian. “International Celebrity: An Artist on Her Own Terms?” In Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity, edited by Quintin Colville with Kate Williams, 138-159. New York: Thames & Hudson Inc; London: In association with the Royal Museums Greenwich, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/994745260.

- _______. “Picturing Performance: Emma, Friedrich Rehlberg and the Attitudes.” In Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity, edited by Quintin Colville with Kate Williams, 160-173. New York: Thames & Hudson Inc; London: In association with the Royal Museums Greenwich, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/994745260.

- Shilliam, Nicola. “Cocardes Nationales and Bonnets Rouges: Symbolic Headdresses of the French Revolution.” Journal of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Vol. 5 (1993): 104-131. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5543776236.

- Siegfried, Susan. The Art of Louis-Léopold Boilly: Modern Life in Napoleonic France. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1025183334.

- Tableau Général du Goût, des Modes et Costumes de Paris, 1797-1799. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k311724g?rk=21459;2.

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/77806804.

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600-1930. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1074444804.

- Weston, Helen D. “Representing the Right to Represent: The ‘Portrait of Citizen Belley, Ex-Representative of the Colonies’ by A.-L. Girodet.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, No 26 (Autumn 1994): 83-99. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5542692367.

- Williams, Kate. “Epilogue: Emma Hamilton in Fiction and Film.” In Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity, edited by Quintin Colville with Kate Williams, 246-271. New York: Thames & Hudson Inc; London: In association with the Royal Museums Greenwich, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/994745260.

- Willms, Johannes. Paris, Capital of Europe: from the Revolution to the Belle Epoque. Trans. Eveline L. Kanes. New York/London: Holmes & Meier, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/51651496.

- Wrigley, Richard. The Politics of Appearances: Representations of Dress in Revolutionary France. Oxford & New York: Berg, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/916401556.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1790-1799

Rulers:

- England: George III (1760-1820)

- France: Louis XVI (1774-1791)

- Spain: Charles IV (1788-1808)

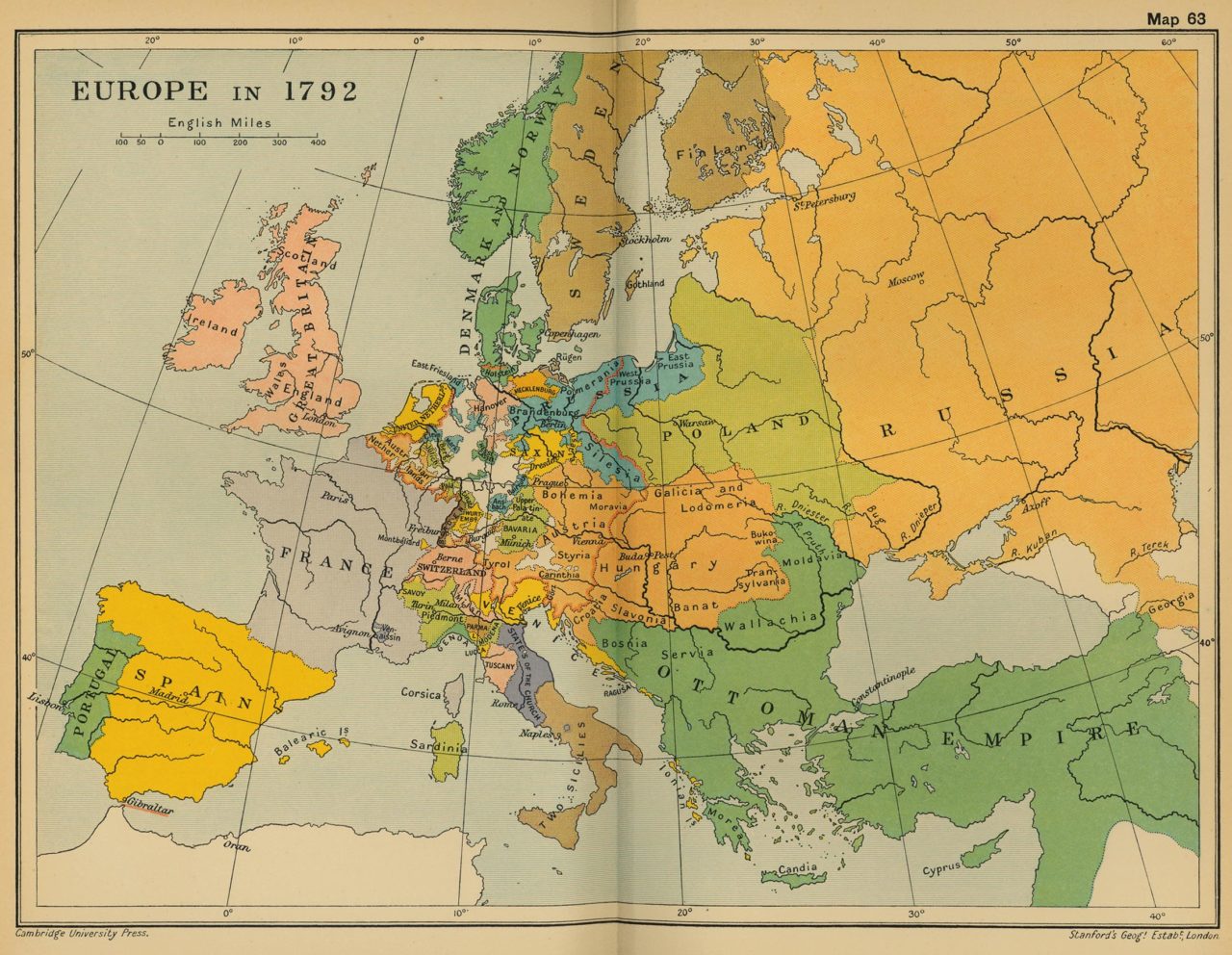

Europe in 1792. Source: emmersonkent.com

Events:

- 1790 – United States President George Washington gives the first State of the Union address, in New York City.

- 1790 – Louis XVI of France accepts a constitutional monarchy.

- 1793 – The Louvre is officially opened in Paris, France.

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Fashion Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 18th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.