OVERVIEW

The 1640s saw womenswear trend in a softer and slightly simpler direction, with low necklines and billowing three-quarter length sleeves often in satin of a single color. With much of Europe at war, menswear took on a more militaristic edge and a parallel simplification, with the wearing of buff coats widely adopted in England.

Womenswear

The 1640s witnessed a gradual simplification of dress for both men and women. Soft, lustrous satins were worn without a great deal of additional surface ornamentation. Lace collars and cuffs were still worn; pearls remained extremely popular both as necklaces, but also as earrings, dress and hair ornaments. François Boucher comments on these changes in A History of Costume in the West (1997):

“the line of costume had been progressively simplified during this quarter century. Width had decreased for men and women alike; superfluous ornaments had disappeared, and even hairstyles had become more restrained.” (256)

This newfound simplicity was embraced by painters, as can be seen in a portrait of Henrietta Maria, Queen Consort of England (Fig. 1). She wears a shimmering blue satin dress, with expansive sleeves, whose open seams are closed by golden eagle brooches. The neckline is extremely low-cut, granting great prominence to her breasts. Golden eagle brooches extend down the center front of her bodice and skirt. She notably wears no lace collar or cuffs, which may have been a further simplification of dress by the painter or more likely reflected her actual dress.

A portrait of a lady of the Grenville family (Fig. 2) similarly omits a lace collar and cuffs and features a similarly plunging neckline. She also has metal brooches closing the gaps in her sleeves and bodice front. The gaps reveal the white linen of her chemise—the foundational layer of women’s dress at the time. Here notably her sleeves are lined in a contrasting fabric of pale pink. The Tate highlights another striking feature:

“the bunch of fresh flowers pinned in the lady’s hair. They are tulips, a fashionable and highly prized commodity, recently introduced from the Netherlands, where during the 1630s they were the subject of financial speculation on an immense scale.”

Fig. 1 - Workshop of Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). Queen Henrietta Maria of England, 1640s. Oil on canvas; 131.3 x 102 cm. Copenhagen: Statens Museum for Kunst, KMSsp240. Source: SMK

Fig. 2 - Gilbert Jackson (English, 1600 – after 1648). A Lady of the Grenville Family and her Son, 1640. Oil on canvas; 74.2 x 60.8 cm. London: Tate, T03237. Source: Tate

Fig. 3 - Gerard van Honthorst (Dutch, 1592-1656). Willem II (1626-50), Prince of Orange, and his wife Maria Stuart (1631-60), 1647. Oil on canvas; 302 x 194.3 cm (118.8 x 76.4 in). Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, SK-A-871. Source: Rijks

Fig. 4 - Bartholomeus van der Helst (Dutch, 1613-1670). Portrait of a Woman, 1649. Oil on canvas; 70 x 60 cm. St. Petersburg: Hermitage, ГЭ-6833. Source: Hermitage

Fig. 5 - Gerrit van Honthorst (Dutch, 1592 - 1656). Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, 1642. Oil on canvas; 205.1 x 130.8 cm. London: The National Gallery, NG6362. Bequeathed by Cornelia, Countess of Craven, 1965. Source: The NGA

Fig. 6 - Wenceslaus Hollar (Bohemian, 1607–1677). Winter, from The Seasons, 1643–44. Etching; 26 × 18 cm (10 1/4 × 7 1/16 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018.846.4. Gift of Barbara E. Fox in Memory of Howard A. Fox, M.D., 2018. Source: The Met

Mary Stuart (Fig. 3) is dressed in daffodil-colored satin, again without lace collar or cuffs; her pinned back sleeves also seem to be made of satin, though were more likely linen. The brooches that pin back the sleeves and close the open seams at her shoulder are made of large pearls. Her white stomacher is adorned with bands of gemstones set into gold that bridge the gap between the two sides of her bodice. Her neckline is low and nearly off-the-shoulder, as in the previous two portraits.

Bartholomeus van der Helst’s 1649 portrait of a woman (Fig. 4) shows that bodices sometimes ended below the bust itself, which is here covered by her gold-lace-edged chemise. She does not wear brooches as all her seams are closed, but their edges are marked by elaborate silver metallic lace. She wears an asymmetrical string of pearls attached by a brooch between her breasts and draped to her left shoulder.

Elizabeth Stuart (Fig. 5), Queen of Bohemia, wears a more somber version of the decade’s trends, as Valerie Cumming notes in A Visual History of Costume: The Seventeenth Century (1984):

“A somber illustration of the emerging line of fashionable dress in the 1640s… The neckline is rounder, closely mirrored by the curve of the deep lace collar. The waistline is longer, terminating in a substantial boned peak which pushes the fullness of the skirt to the sides and back of the waist. The sleeves are less bulky, and a type of turned-back cuff is appearing, pinned back over the rolled-up smock sleeve.” (70)

These pinned-back sleeves exposed most of women’s forearms, so not surprisingly at the same time: “Large fur muffs were a popular, but costly, accessory to winter dresses in the 1640s” (Brown 125).

A 1643 etching by Wenceslaus Hollar titled Winter, shows an English woman dressed for the season with a large muff, fur stole, and even face mask (Fig. 6)

Fig. 7 - Gerard van Honthorst (Dutch, 1592-1656). Portrait of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg, and his Wife Louise Henriette, Countess of Orange-Nassau, 1647. Oil on canvas; 302 × 194.3 cm (118.9 x 76.5 in). Amsterdam: Rijks Museum, SK-A-873. Nationalization 1795 Sep-1798. Source: Rijks

Fig. 8 - Anselm van Hulle (Flemish, 1601-1674). Anna Margareta von Haugwitz (1622 – 73), 1649. Oil on canvas; 237 x 178 cm (93.3 x 70.07 in). Håbo, Sweden: Skokloster Castle, LSH_T8444. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 9 - Benjamin Block (German, 1631-1690). Henriette Luise von Württemberg, 1643. Kulmbach: Plassenburg Castle. Source: Wikipedia

Louise Henriette (Fig. 7), Countess of Orange-Nassau, wears a more lavish silver satin version of the contemporary dress style with large lace collar and cuffs. Notably her skirt still opens in the front to reveal a matching petticoat and the surface of her bodice and skirt is covered with silver lace. Anna Margareta von Haugwitz (Fig. 8) wears a very similar gown, but her petticoat is more noticeable as it contrasts with the black bodice and skirt. Her petticoat seems to be covered entirely in silver and gold brocade designs and matching pearl bracelets wrap seven times about her wrist—clearly not everyone went in for the newfound simplicity.

Similar extravagance is in evidence in the 1643 portrait of Henriette Luise von Würtemberg (Fig. 9). Her black skirt seems to be made of a satin woven with golden floral designs; its v-shaped opening is edged in gold metallic lace and reveals an orange silk petticoat also woven with gold designs. She still wears a love lock alongside a staggering array of necklaces, brooches, pendants, bracelets, rings and earrings. Another example of the “more is more” philosophy embraced by some German women in this period is the Portrait of Anna Rosina Marquart (Fig. 10), who wears a fantastic lace standing collar that circles her face like a bicycle wheel. She still wears the heavy gold chains that had been favored by Germans of both sexes in the 16th century. Her black dress contrasts effectively with the white of her lace collar and cuffs and highlights the gold chains.

Fig. 10 - Michael Conrad Hirt (German, 1613-1671). Portrait of Anna Rosina Marquart, 1642. Oil on canvas. Lübeck, Germany: St. Annen Museum. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 11 - Ferdinand Bol (Dutch, 1616–1680). Portrait of a Woman, 1642. Oil on canvas; 87.3 x 71.1 cm (34 3/8 x 28 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.95.269. Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915. Source: The Met

Fig. 12 - Carlo Francesco Nuvolone (Italian, 1609-1662). Portrait of a Lady, 1647-49. Oil on canvas; 200 x 120 cm (78.7 x 47.2 in). Bologna: Collezioni Comunali d'Arte di Palazzo d'Accursio. Source: Wikipedia

The Dutch by this period had long embraced black, having inherited it from Spain while under Spanish control, and then embraced its supposed somberness when the Protestant reformation arrived. As Ferdinand Bol’s portrait of an unknown woman (Fig. 11) reveals, however, this did not mean Dutch women’s dress was simple. As in the portrait with Anna Rosina Marquart, the black dress fabric sets off the elaborate three-tiered lace kerchief and cuffs. Her stomacher seems to be made of green satin overlaid with black and metallic silver lace. She wears many stranded pearl bracelets and carries a fan, a commonly-seen accessory in this period (Figs. 7, 9, 11, 12).

Some Italian women maintained earlier styles as in Carlo Fancesco Nuvolone’s portrait of an unknown woman (Fig. 12). Here her bodice still has shoulder wings, a trend of the 1610s and she still wears a standing lace collar, where fallen ones were far more common by this period elsewhere in Europe as we’ve seen. The Spanish influence remained strong as Davenport reports: “In 1644, Evelyn notes the ‘Spanish mode and stately garb’ of Genoa and the persistence in Venice of fashions which have endured for a century and a half” (505).

In Spain, the new elliptically shaped Spanish farthingale became firmly established, as can be seen on Maria Teresa, Infanta of Spain (Fig. 2 in the Children’s Wear section). Boucher explains the transition:

“Toward 1640-48 noblewomen and court ladies replaced their bell farthingales with a very broad type of skirt support, worn on the hips…. Their garde-infant was a little flattened at the front and behind, and spread out at the sides.” (278)

Fashion Icon: Mary Villiers, Duchess of Richmond and Lennox

Fig. 1 - Circle of Sir Anthony van Dyck (Dutch, 1559-1641). Portrait of Lady Mary Villiers (1622-1685) as Saint Agnes, 1640. Oil on canvas; 215.3 x 133.3 cm (84 3/4 x 52 1/2 in). Private Collection. Source: Christie's

Lady Mary Villiers (1622-1685) was the daughter of the George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham (see “Fashion Icon” section in 1620-1629), and Katherine Manners, 19th Baroness de Ros. She married at 12, but her young husband, Charles, Lord Herbert, died of smallpox the next year. In 1637, she married James Stewart, the 4th Duke of Lennox, who became Duke of Richmond in 1641. In the 1640s, Mary was Duchess of Richmond and Lennox; she and James had two children—the first born in 1649, when Mary was 27. Some scholars believe Mary was the author of poetry written under the pseudonym Ephelia, most famously, Female Poems by Ephelia (1679):

“Lady Mary … was known not only for her beauty but for her wit, and recent research has established that she was very probably the anonymous poetess at King Charles II’s court who published as ‘Ephelia’ …. This argument would suggest that Lady Mary Villiers was the most highly-placed, publishing woman writer of the Stuart period.” (ephelia.com)

A rather unusual portrait depicts Mary as Saint Agnes (Fig. 1), the patron saint of chastity and purity—an unusual choice for the now twice-married eighteen-year-old. She wears the low-cut satin gown then fashionable, with gaps in the seams closed by pearl brooches. Pearls also dangle from her ears, adorn her neck and the center front of her bodice, which does not feature a lace collar. Lace cuffs are also omitted in the portrait; the skirt is finished with a scalloped edge. The pale blue of her dress is lightly accented by a sky-blue silk drapery that hangs over her right shoulder and then behind her.

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. Mary Villiers, Duchess of Richmond and Lennox (1622 – 85), ca. 1640. Oil on canvas; 104 x 89 cm (40.94 x 35.03 in). Håbo, Sweden: Skokloster Castle. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 3 - Circle of Anthony van Dyck. Lady Mary Villiers, ca. 1640s. Oil on canvas; (39 1/2 x 29 1/2 in). Private Collection. Source: MutualArt

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Mary (Villiers) Stuart, Duchess of Lennox and Richmond, ca. 1640s. Oil on canvas; 120 x 96.5 cm (47 1/4 x 38 in). San Marino: Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, 25.21. Source: Huntington

Mary would remain consistent in her stylistic choices in her portraiture of the 1640s. A portrait from about the same time (Fig. 2) has the same low neckline and pearl brooch closures. The gown here is made of perhaps black satin, with a white stomacher, and a teal drapery hangs over her right shoulder and is held up in her left hand. More shimmering satin is in evidence in a similar portrait (Fig. 3), which omits any hint of her chemise cuffs at the elbow and gives only the barest indication of the chemise at her low neckline, edged in clusters of pearls. The cuffs return in a fourth portrait (Fig. 4) in the collection of the Huntington, where she appears with a ducal coronet resting on the windowsill behind her.

She was a fixture at the court of Charles II and befriended his wife, Catherine of Braganza, with whom she went on a bit of a shopping adventure:

“In October 1670 the duchess, with the queen, and her friend the Duchess of Buckingham decided to go to a fair near Audley End disguised as country women for a ‘merry frolic’, dressed in red petticoats and waistcoats. The costumes were outlandish rather than convincing, and they began to draw a crowd, when they tried to buy stockings and gloves their speech was also conspicuous. A member of the crowd recognised the queen from a dinner she had attended. The party returned followed by as many people at the fair as had horses.” (Wikipedia)

Menswear

Menswear of the 1640s initially maintained some elements of the 1630s including large lace collars on the shoulders and leather boots with deep cuffs. In the portrait of Ulrik Christian Gyldenløve from 1645 (Fig. 1), we still see paned leg-of-mutton sleeves and paning on the upper torso, which was also trendy in the 1630s. But we also see hints of new directions in men’s fashion as Brown explains:

“In the mid-1640s doublets and breeches became much shorter, with breeches gradually getting fuller, finishing in a straight line at the knee. Referred to as petticoat breeches, they resembled a skirt and were worn with underdrawers with decorative edging ‘canions’ that hung beneath the hem” (122)

While Gyldenløve’s breeches don’t yet resemble a skirt, the heavy ribbon loop decoration at their edges will only become more popular. He also wears a shortened doublet that is still largely unbuttoned, revealing his shirt beneath. A cape is draped fashionably over his shoulder.

Endymion Porter has many of the same dress elements in his portrait from about the same time (Fig. 2), though he has abandoned leg-of-mutton sleeves in favor of the now more fashionable sleeves with open seams. As Valerie Cumming points out in her Visual History of Costume: The Seventeenth Century (1984), Porter’s outfit is also a blend of old and new trends:

“The collar could have been worn in the 1630s, but the unstarched cuffs are typical of the 1640s. The high-waisted doublet, with its deep basque, has fewer buttons, allowing a ruffle of lace on the shirt front to assume prominence alongside the ribbon loops at the top of the breeches… The fuller line of the 1640s is broken by billows of linen and ruffles of lace and ribbon.” (72)

The rifle and dead rabbit are perhaps veiled allusions to the ongoing English Civil War, which broke out in 1642 and would eventually result in the execution of King Charles I in 1649 along with some of his Cavalier supporters.

Fig. 1 - Abraham Wuchters (Danish, 1610 - 1682). Ulrik Christian Gyldenløve, son of Christian IV and Vibeke Kruse, 1645. Oil on canvas; 208 x 123 cm (81.8 x 48.4 in). Copenhagen: Statens Museum for Kunst, KMS617. Kleivenfeldts auktion 1777, nr. 137 (kaldet Valdemar Christian), 1851. Source: SMK

Fig. 2 - William Dobson (English, 1611-1646). Endymion Porter, ca. 1642–5. Oil on canvas; 149.9 x 127 cm. London: Tate, N01249. Purchased 1888. Source: Tate

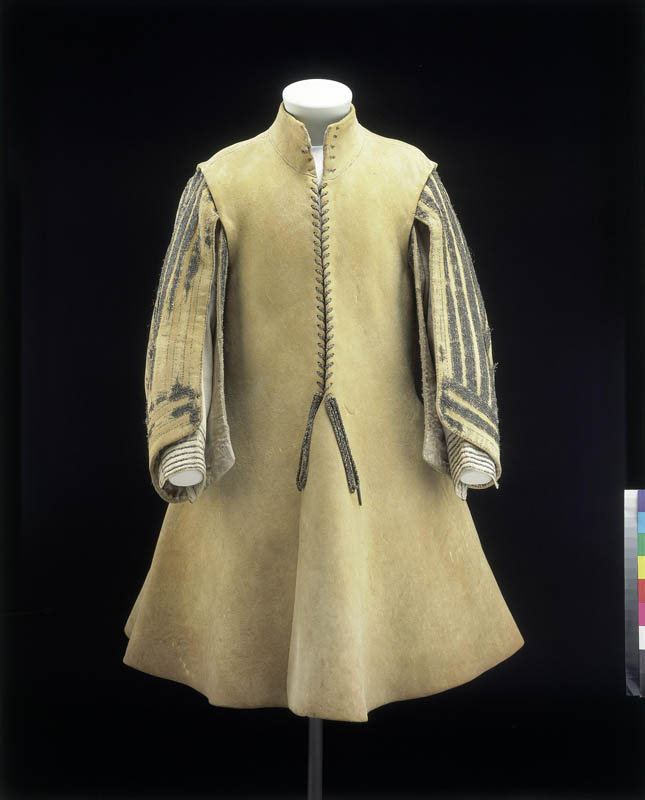

Fig. 3 - Maker unknown (English). Buff leather coat with silver-gilt braid trimming, 1640-1650. Leather, with whalebone stiffening in the collar and silver-gilt braids; height: 103 cm, width: 68 cm skirt, width: 45 cm shoulders, width: 61 cm elbow to elbow. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.34-1948. Source: V&A

Fig. 4 - John Weesop (Flemish, Died: 1652). Sir Henry Gage, 1640s. Oil on canvas; 127.6 x 99.1 cm (50 1/4 x 39 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG2279. Transferred from Tate Gallery, 1957. Source: The NPG

As Cumming notes, “The contrast between the exigencies of warfare and the rich dress of many of its combatants was a feature of the Civil War period” (79). One of the most commonly seen practical concessions to the war was the buff coat, a leather version of the doublet or jerkin. The Victoria & Albert Museum has a 1640s buff coat (Fig. 3) in its collection, of which it writes:

“The buff coat was a feature of military dress during the 17th century, usually worn under a breastplate. Originally these garments were made of European buffalo (or wild ox) hide, which is where the term ‘buff’ comes from. By the mid-17th century, they were most frequently made of oil-tanned cow leather. The thick leather made the coat good protection, not only against musket balls and sword cuts, but also from the friction of the armoured plate worn over it.”

A portrait of Sir Henry Gage (Fig. 4) features just such a usage of the buff coat, as Gage wears a metal armor breastplate over his leather jerkin. But at the same time, his doublet sleeve seams gape tremendously to reveal his billowing linen shirt. The doublet material itself appears to be a lavish gold brocade textile. At his neck he wears a “small linen collar … tied with a lavishly tasseled pair of strings” (Cumming 79). Notably such a reduced collar was not only practical, but also fashionable in France, as the 1644 Les Loix de la Galanterie remarks “our collars are so small that they are like sleeve cuffs” (quoted in Waugh 45).

Fig. 5 - Diego Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660). King Philip IV of Spain, 1644. Oil on canvas; 129.9 x 99.4 cm (51 1/8 x 39 1/8 in). New York: The Frick Collection, 1911.1.123. Henry Clay Frick Bequest. Source: Frick

Fig. 6 - Maker unknown (English). Man's ensemble. Cloak, doublet and breeches in gold satin, 1635-45. Satin, pinked, with applied braid, lined with linen, hand-sewn. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.58 to B-1910. Source: V&A

Fig. 7 - Benjamin Block (German, 1631-1690). Albrecht von Brandenburg-Ansbach (1620-1667), 1643. Kulmbach: Plassenburg Castle. Source: Wikipedia

King Philip IV of Spain (Fig. 5) was also dressed lavishly while on military campaign when painted by Velázquez in 1644. This was a notable break with Philip’s typical fashion avoidance as Millia Davenport remarks in the Book of Costume (1948):

“In this scarlet military costume and baldric, blazing with metal, … Philip makes his first concession to European fashion, except for his hair which he has gradually allowed to lengthen: wide scalloped collar, open button-edged jacket and slightly widened boot-tops over which lace is turned down.” (649)

His scarlet-colored jerkin with matching baldric and cape appears to be covered in luminous silver embroidery, which coordinates with his slender silver doublet sleeves.

A less opulent version of what Philip wears survives in the Victoria & Albert’s collection (Fig. 6). The doublet, cape and breeches all are made of the same gold satin fabric which is covered all over with pinking and applied braid. The museum explains further:

“This ensemble demonstrates fashionable formal dress for men in the late 1630s and early 1640s. The breeches are long and fairly full in cut, reaching just below the knee. The doublet has a high waist at the sides and back, extending to a point in front. A deliberate opening of the seam on each sleeve allows the fine linen shirt underneath to be seen. No ensemble was complete without a cape, and this example spans almost a full circle. The ornamental technique used on this outfit is unique and complicated. Long narrow strips of satin were braided and ‘pinked’ (holed). Then they were cut into short pieces and arranged vertically and diagonally over the underlying shape of each garment to create a rich and decorative effect.”

A similar decorative approach is perhaps seen in Benjamin Block’s portrait of Albrecht von Brandenburg-Ansbach (Fig. 7), which also features leather boots with spurs, lace boot cuffs and the now fashionable ribbon-loop decoration at the end of the breeches.

Fig. 8 - Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck (Dutch, 1606/1609-1662). Andries Stilte as a Standard Bearer, 1640. Oil on canvas; 104 x 78.5 cm (40 15/16 x 30 7/8 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1998.13.1. purchased 1988 by Mr. and Mrs. Michal Hornstein, Montreal; purchased through by NGA.. Source: The NGA

Fig. 9 - Maker unknown (British). Doublet, ca. 1645. Leather, silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982.183.2a–c. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1982. Source: The Met

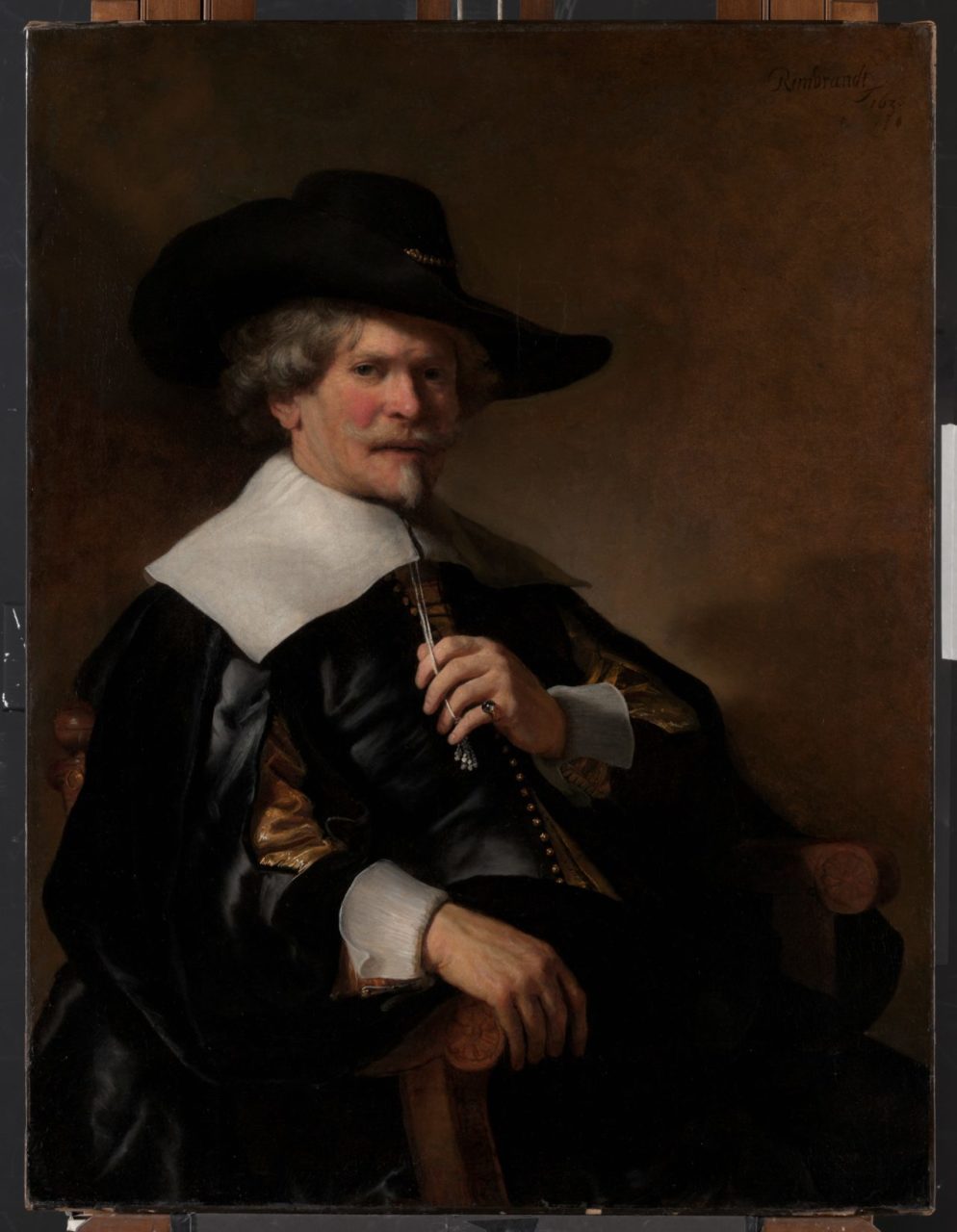

Fig. 10 - Dutch (Amsterdam) Painter (c. 1640-1650). Portrait of a Man Seated in an Armchair, ca. 1640–50. Oil on canvas; 108.3 x 82.6 cm (42 5/8 x 32 1/2 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.1.139. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975. Source: The Met

Some of the swagger of King Philip’s portrait can also be found in the portrait of Andries Stilte as a Standard Bearer (Fig. 8), where he too is ostensibly dressed for military service. Yet his doublet and breeches are made of pale pink satin and edged in expensive lace. Notably his lace collar is gathered into a bow at the front of his neck—a forerunner of the cravat, which will soon replace the large lace collars seen in the first half of the seventeenth century. As the fashion for long hair cascading on the shoulders continued, much of the lace on one’s shoulders would be hidden; it thus became the practice to gather the lace beneath the chin, where it could still be seen. This would be the forerunner of the modern tie. According to the National Gallery of Art:

“Stilte commissioned Verspronck to paint him wearing his sumptuous pink costume right before he resigned his rank to marry. As a married militia officer, Stilte would have worn an elegant black outfit.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has a British doublet of this era in its collection (Fig. 9), which features the same long row of buttons down the forearm as Stilje’s doublet. While the floral brocade pattern may initially seem to be made of gold and silver threads, they are only silk in colors that suggest gold and silver, whereas Sir Henry Gage (Fig. 4) and King Philip (Fig. 5) are painted to suggest the real thing.

A portrait of a man seated in an armchair (Fig. 10) initially gives a somber impression of simplicity given the black of his jerkin and the white plainness of his collar and cuffs, but the open seams of his sleeves reveal luminous golden doublet sleeves. Closer inspection also reveals under his unbuttoned jerkin a line of golden fabric from the doublet and, beneath his somewhat transparent white cuffs, the doublet cuffs themselves softly shimmer. He grasps the band strings of his collar in his left hand (they can be seen properly tied in Fig. 4). So even if married men were expected to adopt black as the National Gallery suggests about Stiltje (Fig. 8), flourishes of dress and of extravagance were still quite possible. In the Childrenswear section below, be sure to notice the bright green silk stockings worn by Sir Arthur Capel (Fig. 1).

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Babies and toddlers were dressed in white gowns as can be seen in the portrait of the Capel Family (Fig. 1). The infant Charles on Lady Capel’s lap has a coral teether on a red satin ribbon tied about his waist. His brother Henry is still dressed in a gown, but the eldest brother Arthur, then aged about 9, wears a pink satin doublet and lace collar like his father. After age 5 or 6, boys began to be dressed as miniature adult men. The two daughters, Elizabeth and Mary, are dressed identically, as was a common practice, and the details of their dress echo those of their mother; for example, they have contrasting satin ribbon laces across their stomachers that are then tied into two bows. They wear lace collars and cuffs and even pearl jewelry like their mother.

The seven-year-old María Teresa (Fig. 2), Infanta of Spain, is already dressed as an adult woman in Spain would be, wearing the new elliptical garde-infant then fashionable as Hill points out in his History of World Costume and Fashion (2011):

“The size and shape of the Spanish court farthingale changed from the conical silhouette to a wide, elliptical form in the early seventeenth century. Attached to the flat front bodice was a wide peplum that softened the hard edge of the hoops.” (408)

Fig. 1 - Cornelius Johnson (Dutch, 1593-1661). The Capel Family, ca. 1640. Oil on canvas; 160 x 259 cm (63 x 102 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 4759. Purchased with help from the Art Fund, 1970. Source: NPG

Fig. 2 - Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo (Spanish, 1612–1667). María Teresa, Infanta of Spain, ca. 1645. Oil on canvas; 148 x 102.9 cm (58 1/4 x 40 1/2 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 43.101. Rogers Fund, 1943. Source: The MET

References:

- “Andries Stilte as a Standard Bearer.” Accessed January 28, 2020. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.104729.html.

- Boucher, François, Yvonne Deslandres, and John Ross. A History of Costume in the West. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/443676264.

- Brown, Susan, ed. Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. New York: DK Publishing, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/840417029.

- V and A Collections. “Coat | V&A Search the Collections,” January 28, 2020. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O78845.

- Cumming, Valerie. A Visual History of Costume: The Seventeenth Century. 3. London: Batsford, 1984. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/9761398.

- Davenport, Millia. The Book of Costume. New York: Crown Publishers, 1948. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/922657048.

- “Ephelia: Recent Acknowledgement & Ducal Portrait of Mary Villiers.” Accessed January 28, 2020. http://www.ephelia.com/e27.html.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950.

- “Mary Stewart, Duchess of Richmond.” In Wikipedia, August 20, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mary_Stewart,_Duchess_of_Richmond&oldid=911686226.

- Tate. “‘A Lady of the Grenville Family and Her Son’, Gilbert Jackson, 1640.” Tate. Accessed January 21, 2020. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/jackson-a-lady-of-the-grenville-family-and-her-son-t03237.

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes, 1600-1900. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927414537.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1640-1649

Rulers:

- England: King Charles I (1625-1649)

- France:

- King Louis XIII (1610-1643)

- King Louis XIV (1643-1715)

- Spain: King Philip IV (1621-1665)

Map of Europe in 1640. Source: Wikimedia

Events:

- 1640 – Independence of Portugal

- 1642 – Rembrandt’s Night Watch

- 1648 – End of Thirty Years War

- 1649-59 – The English Commonwealth is proclaimed, with puritanical Oliver Cromwell at its head. Style in England becomes more subdued as a result.

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 17th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.