OVERVIEW

In 1520-1529, men and women both began to wear shirts with high standing collars ending in a frill at the neck and cuff, which would later evolve into the ruff. Dark colors continued to grow in popularity, as did everything oversize, among them: codpieces, gown sleeves, and elaborate headdresses.

Womenswear

Women’s dress in Spain was becoming more modest, a trend that would later spread across Europe in contrast to the low necklines of decades previous. Daniel Delis Hill elaborates further in his History of World Costume and Fashion (2011):

“Among the style changes inaugurated by the Madrid court was a restriction against open necklines. Partlets, high-collared chemises, and even veils resolved the issue at first until bodices began to be constructed to completely conceal the upper torso to the neck. As bodices were redesigned, they were heavily padded to provide a smooth lay of the fabric.” (378)

Queen Isabella of Portugal, wife of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, demonstrates this new fashion in her 1520s portrait (Fig. 1). Her transparent linen chemise or partlet completely fills the neckline of her dress. As Jane Ashelford notes in her Visual History of Costume: The Sixteenth Century (1983): “the contrast between the rigidity of the upper half of the body and the wide expanse of the oversleeves becomes a marked characteristic of female fashion during the next two decades” (31).

In Italy

In this period Spain exerted a great deal of influence on Italian dress as much of Northern Italy was under Spanish control. François Boucher describes this influence in A History of Costume in the West (1997):

“The court costume of Charles V gave Italy the system of supporting frameworks round the chest and waist and the inflexible arrangement of formal folds, and Italy adapted its rich textiles to these styles.” (224)

Rich Italian silks and velvets abounded in dress of this period and Italian women’s gowns showcased their excellence. Some Italian women (especially those in Venice) retained the low-cut bodices favored in 1510-1519. The broad silhouette seen in figures 2-3 mirrors that found in menswear of the time. As Boucher notes:

“The Italians showed increasing appreciation of women ‘full in flesh’ and, according to Montaigne, ‘fashion them large and stout’. Muralti compared them with wine barrels.” (223-24)

The stiff, padded bodices of the gowns in figures 4-6 are softened by the sumptuous texture of the fabrics. These three women also follow the Spanish trend of the filled-in neckline, with their expansive chemises with beautiful blackwork embroidery visible. The standing ruffled collar that will be a key feature of Italian menswear is also in evidence here. As Milia Davenport remarks in The Book of Costume (1948) Italian sleeve styles were different from those found elsewhere:

“Instead of the funnel or close sleeve of English, French or German gowns, with their neat shoulder line, the sleeve of an Italian gown is apt to be voluminously gathered at the top.” (496)

Fig. 1 - Circle of Master of the Female Half-Lengths (Flemish). Portrait of Isabella of Portugal (1503-1539), 1520s. Oil on oak. Lisbon: Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 2172 Pint. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 2 - Palma Vecchio (Jacopo Negretti) (Venetian, 1480-1520). Portrait of a Young Woman Known as "La Bella", ca. 1518-1520. Oil on canvas; 95 x 80 cm. Madrid: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Inv. no. 310 (1959.2). Source: Thyssen-Bornemisza

Fig. 3 - Paris Bordone (Italian, 1500-1571). Venetian Lovers, 1525-1530. Oil on canvas; 81 x 86 cm (31.9 x 33.9 in). Milan: Pinacoteca di Brera, 1156. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 4 - Bernardino Luini (Milanese, 1480-1532). Portrait of a Lady, 1520/1525. Oil on panel; 77 x 57.5 cm (30 5/16 x 22 5/8 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1937.1.37. Andrew W. Mellon Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 5 - Bartolomeo Veneto (Venetian, 1502-1555). Portrait of a Young Lady, ca. 1520-30. Oil on wood; 93 x 62.2 cm. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 16909. Purchased 1971. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 6 - Agnolo Bronzino (Italian, 1503-72). Portrait of a Lady in Green, ca. 1528-32. Oil on poplar panel; 76.6 x 66.2 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 405754. Source: RCT

Bernardino Luini’s Portrait of a Lady (Fig. 4) features two key Italian accessories: a zibellino, or sable/marten fur pelt that hangs from a chain on her girdle, and her large turban-style headdress. Davenport comments on this headdress style:

“The turbans which the Italians always loved… return in the early XVI c. in huge round forms, ruffled, netted and knotted.” (496)

Bartolomeo Veneto’s Portrait of a Young Lady (Fig. 5) shows a rich burgundy velvet gown with a chemise embroidered in black with elaborate scrollwork; she does not carry a zibellino, but wears gloves, which are increasingly worn by men and women. According to the National Gallery of Canada: “Technical study reveals that the artist made significant changes to her costume and hairstyle as he painted, likely at the request of the sitter, who would have wanted the latest fashions for her portrait.”

Her turban-style headdress is particularly large and extravagant, which nicely balances the fullness of her sleeves. The lack of balance between the sleeve width and the headdress of the Lady in Green (Fig. 6) has provoked debate, as the Royal Collection Trust notes:

“Costume historians are divided over whether the sitter’s clothes are northern Italian or Florentine. Two elements are perplexing: one would expect a headdress of this date to be much larger, matching the sleeves in effect, and the sleeves to be gathered tightly at the elbows, rather than loosely as here.”

Notably her undersleeves are elaborately paned, a trend we first saw in Germany and that remained popular there.

Fig. 7 - Lucas Cranach the Elder (German, 1472-1553). Portrait of Princess Sibylle of Cleve, 1526. Oil on beech wood; 57 x 39 cm (22.4 x 15.3 in). Weimar: Schloss Weimar, G 12. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 8 - Lucas Cranach the Elder (German, 1472-1553). Portrait of Anna Buchner, née Lindacker, ca. 1520. Oil on panel; 40.6 x 27.3 cm (16 x 10 3/4 in). Minneapolis Institute of Art, 57.10. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund. Source: MIA

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown. Wedding dress of Queen Mary of Hungary, 1522. Budapest: Hungarian National Museum. Source: Hungarian National Museum

In Germany and Hungary

Similar paning is seen on the sleeves of Princess Sibylle of Cleve (Fig. 7), who also wears a minutely pleated chemise that closes at the neck with a gold neckband embellished with pearls. Womenswear in Germany remains very similar to that of the previous two decades, though gradually more modest necklines began to appear as they did elsewhere in Europe.

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s portrait of Anna Buchner (Fig. 8) shows the continuing German enthusiasm for heavy gold chains. Gown sleeves remain narrow drawing attention to the hands, where Buchner wears at least twelve rings. Hill comments on this pervasive German trend:

“In the 1520s and 1530s, matching sets of five rings were worn on various fingers, including the thumb and upper joints.” (381)

The neckline of her low-cut bodice is filled in by her chemise and a plastron embroidered with pearls; lacing joins the two sides of the bodice. The sides of the bodice and the cuffs are made of a different silk damask from the rest of the gown. We see the same construction in the wedding dress of Queen Mary of Hungary (Fig. 9) who married King Louis II of Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia in 1522. The dress is one of only a few surviving 16th-century gowns and is made of two different silk damask fabrics with long narrow sleeves. The open bodice is filled in by a pleated chemise ornamented with silver embroidery at the neckline. It’s possible Mary would have worn her hair down for her wedding, as in Cranach’s Portrait of Princess Sibylle of Cleve (Fig. 7). As the Cunningtons note in their Handbook of English Costume in the Sixteenth Century (1954), this was the practice in England:

“Long Hair flowing loose, the head adorned with a gold fillet, caul, billiment or wreath, was worn by brides and their attendants, queens at their coronation, and young girls.” (84).

Fig. 10 - Jean Clouet (French, 1480-1541). Portrait of Marguerite of Navarre, ca. 1527. Oil on oak; 62 x 52.5 cm. Liverpool: Walker Art Gallery, 1308. Presented to the Walker Art Gallery by the Liverpool Royal Institution in 1948. Source: Liverpool Museums

Fig. 11 - Circle of Corneille de Lyon (French, active 1533-1575). Françoise de Longwy, ca. 1527. Oil on panel; 14.6 x 11.7 cm (5 3/4 x 4 5/8 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 19.764. Francis Bartlett Donation of 1912. Source: MFA Boston

In France

Marguerite of Navarre, sister of King François I (see Fashion Icon section below), wears a combination of Italian and German trends in her 1527 portrait by Jean Clouet (Fig. 10). Her gown has the broad silhouette, low-cut bodice and large sleeves popular in Italy, though worn with only the band of the chemise visible at the edge of the bodice. The chemise has a starring role however in her elaborately slashed and puffed sleeves and is also visible at her forearm, where it is embroidered. Her hair is covered in a golden caul or snood and flat black bonnet worn at a fashionable angle. As the Walker Art Gallery notes, “The golden knots on her headdress resemble daisies – marguerites in French.”

Marguerite wears one large pendant necklace ornamented with pearls and gemstones, but also a very narrow second necklace that disappears into her bodice at the bust. One also sees this trend in Corneille de Lyon’s portrait of Françoise de Longwy (Fig. 11) as well among some of the English women discussed below. De Longwy’s pink satin gown has a square-cut neckline and enormous turned back cuffs or oversleeves made of white fur that almost reach her shoulders.

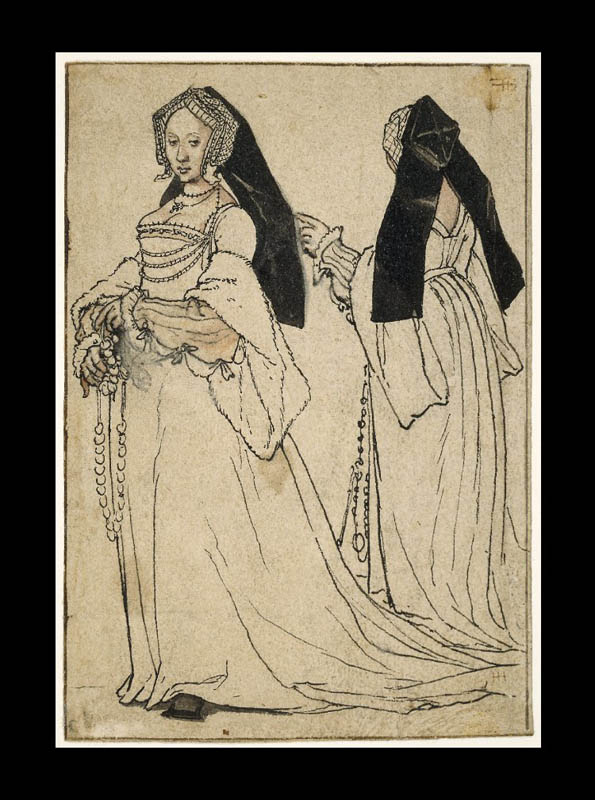

Fig. 12 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Two views of a lady wearing an English hood, ca. 1532-35. Brush drawing in brown ink, tinted with pink and grey wash on off-white paper; 15.9 x 11 cm. London: British Museum, 1895,0915.991. Source: British Museum

Fig. 13 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Mary, Lady Guildford, 1527. Oil on panel; 87 x 70.6 cm (34 1/4 x 27 13/16 in). Saint Louis Art Museum, 1:1943. Source: SLAM

Fig. 14 - Artist unknown. Katherine of Aragon, ca. 1520. Oil on oak panel; 52 x 42 cm (20 1/2 x 16 1/2 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NGP L246. Source: NPG

In England

Under Henry VIII, English women’s dress closely resembled that of French women, excepting the use of the gabled hood rather than the French hood (seen on de Longwy). Hans Holbein’s sketch of an English woman (Fig. 12) reveals the likely construction of de Longwy’s gown and the typical silhouette of English women in this period. It shares her large fur oversleeves turned back almost to the shoulder and the low-cut bodice.

Maria Hayward describes the standard English dress of the period in Dress at the Court of Henry VIII (2007):

“Portraits indicate that necklines were invariably square-cut at the front, but with a V-shaped back which could be either shallow or could reach down to the waistline. Bodice shaping of this type was depicted in Holbein’s drawing of a woman, c. 1528.” (162)

Speaking of the same drawing, Ashelford notes: “The back view shows how pleats in the V-necked bodice lead to the fullness of the trained skirt” and goes on to describe its characteristic gabled hood:

“An English hood of the later style in which the lappets are pinned up on top and the hair is concealed by crossed bands; a linen undercap swerves onto the face. The back view shows how the back of the hood has evolved into a distinctive box-like shape to which are attached two tubes of material.” (33)

Hair ceases to visible beneath the gabled hood circa 1525 as the Cunningtons remark:

“After 1525 the hair was concealed in rolls crossing in the centre. The space under the gable was now invariably filled in by silk sheaths, usually striped and containing the tresses of hair turned up from either side and overlapping in the mid line above the forehead.” (73-74)

Examples of these striped sheaths can be seen in both Holbein’s portrait of Mary, Lady Guildford (Fig. 13) and that of Katherine of Aragon (Fig. 14). It’s likely Holbein’s sketch (Fig. 12) is of Lady Guildford given the close resemblance of their costumes—particularly the gold chains crossing the bodice. Her kirtle sleeves are open along the bottom seam and her chemise is puffed out in the gaps. She seems to have adopted the German trend of wearing five rings on her hand.

Katherine of Aragon’s kirtle sleeves are paned and her turned back oversleeves are cloth-of-gold brocade. The pointed gable of the hood she wears required structural support, an example of which survives (Fig. 15) in the Museum of London.

There were softer alternatives to the rigid gabled hood or even the French hood. One of those was the lettice cap, which was principally worn ca. 1520s-40s and can be seen in Holbein’s portrait of a Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (Fig. 16). The Cunningtons describe its appearance:

“Lettice was a fur resembling ermine, and the lettice cap was not only composed of this fur, but was made in a design of its own. It resembled a large bonnet with the crown raised to a triangular shape above the head, in the spirt of the ‘gable hood’. The front border, fitting close, was cut back to show the hair as far as the temples, and then curving forward to cover the ears, ended at chin level. There was no fastening.” (80)

Fig. 15 - Maker unknown (British). Gable hood frame, late 15th-early 16th century. Copper alloy; 19.8 x 18.4 cm. Museum of London, Z640. Source: Museum of London

Fig. 16 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (Anne Lovell?), ca. 1526-28. Oil on oak; 56 x 38.8 cm. London: National Gallery, NG6540. Bought with contributions from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund and Mr J. Paul Getty Jnr (through the American Friends of the National Gallery, London), 1992. Source: National Gallery

Fig. 17 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Cicely Heron (b. 1507), ca. 1526-27. Black and couloured chalks on paper; 37. 8 x 28.1 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 912269. Source: RCT

Cecily Heron in a Holbein sketch (Fig. 17) wears another variant hood style with some of her hair visible. A slim neckace disappears into her square-cut bodice and her large oversleeves are turned back almost to the shoulder. But the sketch is unusual for revealing dress accommodations made for pregnancy, as Anna Reynolds explains in In Fine Style (2013):

“There was no specific maternity clothing during the period, and accounts do not even reflect adjustments made to existing clothing. One option was to add an additional panel of fabric (known either as a stomacher or placard) between the two sides of a bodice. Or the lacing on the front of the bodice could be loosened, as in Holbein’s portrait of Cicely Heron. This is one of the earliest ‘pregnancy portraits’, a form of self-presentation that enjoyed a particular vogue in England during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.” (53-54)

Fashion Icon: François I, King of France

Fig. 1 - Jean Clouet (French, 1480-1541). François Ier, ca. 1525. Oil on oak; 21.6 x 16.8 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, MI 832. Source: Joconde

Fig. 2 - Jean Clouet (French, 1480-1541). François Ier, ca. 1527-30. Oil on oak; 96 x 74 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, INV 3256. Source: Louvre

François I (1494-1547) became king of France in 1515 and soon became known for the lavishness of his dress. Boucher notes that François was not afraid to import the rich textiles then fashionable:

“François I used his prestige to support the vogue for the fashions of Genoa, Florence, Venice and Milan, for woven silk stockings and, most of all, for the marvelous silks and velvets imported from Italy.” (231)

He helped popularize the wearing of beards (see 1510-1519) and Henry VIII famously grew out his own beard immediately upon hearing François had done so, pointing to his trendsetter status. The famous “Field of the Cloth of Gold” meeting in 1520 between François and Henry was a perhaps unparalleled fashion competition, where cloth-of-gold was much in evidence, as the name given to the event later suggests. English and French lords were said to have bankrupted themselves to pay for their wardrobes. The “Chronicle” of the contemporary English lawyer-historian Edward Hall describes François I’s dress:

“The French King and his band were appareled in purple satin, branched with gold and purple velvet, embroidered with [Franciscan] friars’ knots, and in every knot were pansy flowers, which together, signified ‘Think of Francis.’” (Davenport 473)

François I was a great patron of the arts, who brought Leonardo da Vinci to his court and famously purchased the Mona Lisa. Da Vinci perhaps advised him on the construction of the magnificent Château de Chambord, one of many chateaus he built or expanded.

Portraits reveal his affinity for boat-neck linen shirts edged with a frill decorated with blackwork embroidery; indeed all the shirts in figures 1-4 could be the same. A likely later portrait (Fig. 5) shows his adoption of the standing collar that became popular in the 1530s. François also seems to be wearing virtually the same hat in portraits of this era (though that in Fig. 1 is notched). Bonnets with ‘halo’ brims like these became popular in the 1520s:

“the moderate turned-up brim hid the crown, encircling the head like a halo, and was usually bordered with ostrich tips, or trimmed with a single ostrich feather placed horizontally and roping over one side. A medallion or brooch was generally placed over one temple.” (Cunnington 45)

François’s hats are also decorated by golden aiguillettes (or decorative metal tags/tips). His doublets/jerkins are ornamented by slashing (Fig. 1), embroidery and open seaming (Figs. 2-3), beadwork and knots (Fig. 4), and passementerie/cord (Fig. 5). As became common in the 1520s, he wears a sword and carries gloves. In figures 2 and 3, he wears an alternative to the gown, the “loose and fairly short” chamarre, described by Boucher, “open in front, lined with fur or contrasting silk, and with sleeve openings circled with puffed wings, often decorated with coloured braid or passementerie” (231). In figure 3, his jerkin has an ample skirt and he wears a prominent codpiece, as well as paned hose, stockings held up by garters, and duckbill shoes.

François’ intense fashion rivalry with Henry VIII would extend into the 1530s, as we’ll see. As a powerful and successful king ruling one of the most powerful countries in Europe, François set the fashion of the day in France and influenced it elsewhere.

Fig. 3 - Studio of Jean Clouet (French, 1480-1541). François Ier, ca. 1527-30. Château de Chambord. Source: Google Arts & Culture

Fig. 4 - Joos van Cleve (Netherlandish, 1485-1541). Portrait of Francis I, King of France, ca. 1532-33. Oil on panel; 72.1 × 59.2 cm (28 3/8 × 23 5/16 in). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Cat. 769. John G. Johnson Collection, 1917. Source: PMA

Fig. 5 - French school. Portrait of Francis I of France, ca. 1530. Oil on panel; 32.5 x 25 cm (12.7 x 9.8 in). Château de Chambord. Source: Wikipedia

Menswear

Moretto da Brescia’s 1526 portrait of a man (Fig. 1) gives a rare full-length picture of 1520s menswear trends. As Ashelford explains, Spanish influence became widespread in Italy in this period:

“The sleeveless jerkin and sombre colours worn by this elegant man reflect the dominance of Spanish fashion in Italy after the decisive battle of Pavia in 1525. The unusual head-wear is typically Italian… a red pleated bonnet with a medallion of St. Christopher is worn over a gold turban-like coif.” (27)

He has a beard and mustache as was typical by this period and his shirt, ornamented with gray and gold embroidery, has a high standing collar with a very narrow frill that will eventually become the ruff. His black jerkin is worn atop his slashed doublet and hose; the white of his shirt is visible through the slashes and at his frilled cuff. His brown hose is lined in a fabric of the same color. He has a prominent codpiece and carries a sword and gloves. Swords began to be regularly worn as part of civilian dress in the 1520s. His black shoes are extremely wide at the toe and a very low vamp or upper that leaves much of the top of the foot exposed. He wears a black damask cloak over one shoulder, which was a new trend that would become dominant in the second half of the century, displacing the gown.

As Boucher notes:

“Men wore this Spanish costume with melon-shaped upper stocks and dark-coloured doublets. They took to heart Rafaella’s maxim, ‘Costume is poor when cloth is coarse’, and looked above all for quality and beauty in the materials used.” (224)

Fig. 1 - Moretto da Brescia (Italian, 1498-1554). Portrait of a Man, 1526. Oil on canvas; 201 x 92.2 cm. London: National Gallery, NG1025. Source: National Gallery

Fig. 2 - Titian (Venetian, 1490-1576). Man with a Glove, ca. 1520. Oil on canvas; 100 x 89 cm (39.3 x 35 in). Paris: Musée du Louvre, INV 771. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 3 - Jan Gossart (called Mabuse) (Netherlandish, ca. 1478–1532). Portrait of a Man, ca. 1520-1525. Oil on wood; 47 x 34.9 cm (18 1/2 x 13 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 32.100.62. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

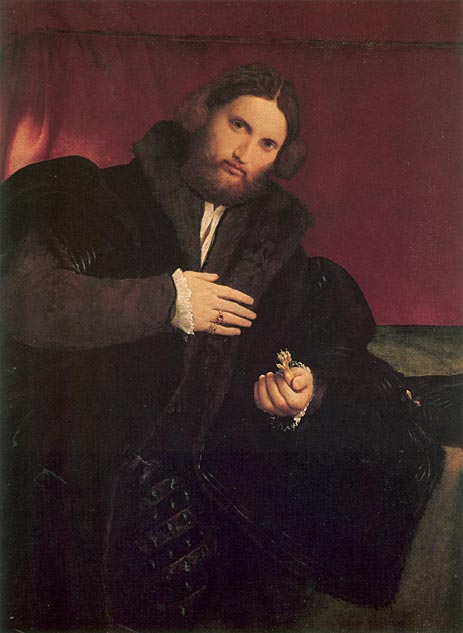

Fig. 4 - Lorenzo Lotto (Italian, 1480-1556). Man with a Golden Paw, ca. 1527. Oil on canvas; 95.5 x 69.5 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie, 265. Source: KHM

Titian’s Man with a Glove (Fig. 2) is similarly severe in color palette and even more restrained in terms of decorative detail. His black jerkin has a similar cut to that seen in Moretto da Brescia’s portrait, ending at the neck and worn open down the chest, revealing the shirt. The shirt has a standing collar with narrow frill, as do the cuffs, but no embroidered decoration. He wears one kidskin glove and holds the other. He may be wearing a chamarre, or loose overgown, seen previously on François I.

Spanish influence extended to the Netherlands, where Jan Gossart’s gray and black-clad Portrait of a Man (Fig. 3) wears the earlier style of square-cut doublet/jerkin and fur-lined gown. Lorenzo Lotto’s Man with a Golden Paw (Fig. 4) shares the somber tonalities of the other portraits on first glance, but also wears hose slashed to reveal a rich green lining fabric.

Fig. 5 - Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci) (Florentine, 1494-1557). Portrait of a Halberdier (Francesco Guardi?), 1529-30. Oil on panel transferred to canvas; 95.3 x 73 cm (37 1/2 x 28 3/4 in). Los Angeles: Getty Museum, 89.PA.49. Source: Getty

Fig. 6 - Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) (Venetian, 1490-1576). Federico Gonzaga, Ist Duke of Mantua, 1529. Oil on panel; 125 x 99 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P000408. Source: Prado

Fig. 7 - Girolamo Romanino (Italian, 1485-1566). Portrait of a Man, ca. 1520-1525. Oil on panel; 83 x 72 cm (32.6 x 28.3 in). Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts. Source: Wikipedia

Indeed, Italian fashion still retained a colorful exuberance as Pontormo’s portrait of a young foot soldier (Fig. 5) attests. His costume is described by Davenport:

“The slope-shouldered, narrow-hipped Florentine male silhouette; sleeve without rolls or picadills at shoulder, widest below elbow; low standing collar, easy and often open with little display of elaborate linen; almost not jewelry. Aiglettes sparsely but functionally used. Cod-piece differs from tailored and decorated English-French form. Short hair; smooth-shaven face.” (499)

The portrait allows us to see how the doublet was laced to the hose with cords ending in decorative metal tips, or aigulettes. The red hose is slashed, as is the codpiece, which is sizable. A sword hangs from his baldrick; the wearing of swords prompted a shift in fashion for accessories, as Davenport explains:

“With the increasing use of swords and daggers, diagonally slung, in the everyday dress of gentlemen, there is a decrease in the importance of chains, which tend to become cords or scarves, carrying a pendant. Increasing use of precious tags, aiglettes; rings.” (375)

Titian’s portrait of Federico Gonzaga (Fig. 6) shows him in a sapphire blue velvet doublet, with pickadils at the shoulder, worn atop a shirt embroidered unusually also in blue. His hose and codpiece are of a bright red hue. Niccolò Machiavelli records a quip by Cosimo the Elder “in his Istorie (1526) that ‘two yards of pink cloth can make a gentleman’” (Currie 5). Of course voided velvet with gold brocade will also work, as in Girolamo Romanino’s portrait of an unknown man (Fig. 7), though the doublet cut is more similar to that of 1510-1519.

Fig. 8 - Bartolomeo Veneto (Venetian, 1502-1531). Portrait of a Gentleman, ca. 1520. Oil on panel transferred to canvas; 76.8 x 58.4 cm (30 1/4 x 23 in). Washington, D.C: National Gallery of Art, 1939.1.257. Samuel H. Kress Collection. Source: National Gallery of Art

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown (Flemish). Hat badge with St George and the dragon, ca. 1520. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 442208. Source: RCT

Fig. 10 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Sir Henry Guildford, 1527. Oil on oak panel; 82.7 x 66.4 cm. Windsor Castle, RCIN 400046. Source: Royal Collection Trust

The broad silhouette is also in evidence in Bartolomeo Veneto’s portrait of a gentleman (Fig. 8). He wears a boat-neck cut shirt and hat with badge like those seen on François I above.

A hat badge said to have belonged to Henry VIII (Fig. 9) that depicts St. George and the dragon gives some sense of the incredible detail and luxury of such items (Hayward 113). Indeed, while the taste for extravagant display may have been waning in Spain and Italy, it remained strong in England and France. For discussion of French men’s fashion, see the Fashion Icon section about François I, King of France, above. As Boucher notes:

“During the first quarter of the century, as we have seen, French costume continued in its earlier style, though with greater richness in material and decoration, reciprocally influenced by Italian fashions.” (230)

Holbien’s portrait of Sir Henry Guildford, Comptroller of Henry VIII’s Household, gives us some idea what the dress of his court was likely like during the meeting at the “Field of the Cloth-of-Gold” discussed in the Fashion Icon section above. Reynolds describes how such lavish textiles were produced:

“Additional metal threads could be woven through a piece of fabric, usually silk, to produce the most expensive fabrics known as cloth-of-gold or cloth-of-silver – restricted to the nobility by legislation in the sixteenth century. Metal threads were produced through a variety of techniques. Filé threads, for example, were strips of silver-gilt hammered to a very fine thickness, then wrapped around a silk core. Holbein’s portrait of Sir Henry Guildford depicts the courtier wearing a doublet of cloth-of-gold woven into a pomegranate pattern.” (149)

See the companion portrait of Mary, Lady Guildford, above (Fig. 13).

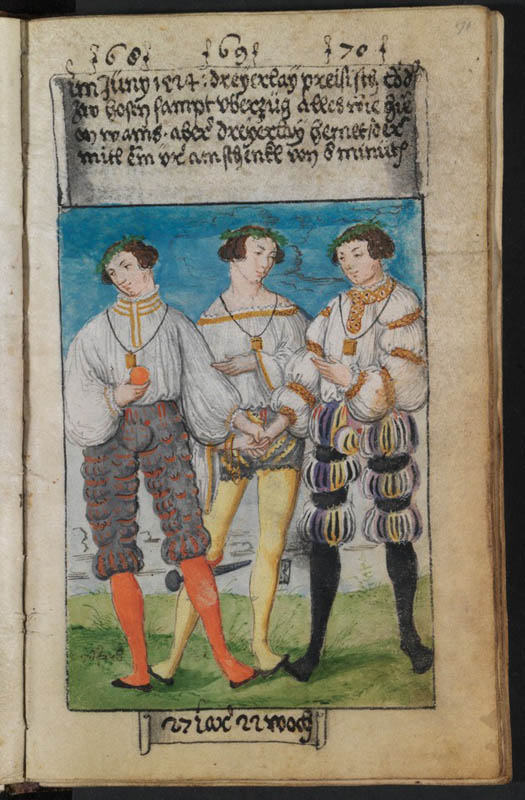

Fig. 11 - Narziss Renner (German, 1502-1536). Matthäus Schwarz (26 years. 1/2 month), March 1523. Braunschweig: Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum. First Book of Fashion (2015). Source: New York Review of Books

Fig. 12 - Kolman Helmschmid (German, active 1471-1532). Landsknechts armor, 1523. Iron, etched ornamnent and leather. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, A 374. Source: KHM

Fig. 13 - Narziss Renner (German, 1502-1536). Matthäus Schwarz, June 1524. Braunschweig: Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum. First Book of Fashion (2015). Source: Atlantic

Fig. 14 - Barthel Beham (German, 1502–1540). Chancellor Leonhard von Eck (1480–1550), 1527. Oil on spruce; 56.2 x 37.8 cm (22 1/8 x 14 7/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 12.194. John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1912. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In Germany, slashing and pinking remained popular decorative treatments for doublets and hose. Matthäus Schwarz (Fig. 11) boasts of his doublet’s elaborate use of slashing: “In March 1523. The doublet of fustian, which has 4,800 slashes with velvet rolls all in white” (112). This enthusiasm for slashing even extended to armor, as in this 1523 suit (Fig. 12) where the metal plate is etched to mimic slashing.

A 1524 image of Schwarz (Fig. 13) shows hose with slashing and pinking that reveals bright fabric below as seen in the portrait by Lotto (Fig. 4). The caption reads: “In June 1524. Three types of Prussian leather as hose and over-hose, everything as shown, without doublet, but three kinds of shirts” (119). Unusually, he wears no doublet, which allows the variety of shirts being worn to be seen. All are decorated with gold embroidery and have a slight frill at the neck, though the central one has the lower cut profile previously popular. As the Cunningtons note, “by 1525 [the shirt] was usually cut high, and finished with a band fitting round the neck.” (17)

The severely minimal portrait of Chancellor Leonhard von Eck, who served at the court of Duke William IV, shows just such a shirt and testifies that not everyone sought decorative excess in dress.

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Children of the 1520s continued to be dressed as miniature adults. François III (Fig. 1) is dressed in much the same manner as François I (see Fashion Icon above), even down to the bonnet with halo brim and hat badge. Of Madeleine of France (Fig. 2), Jane Huggett in The Tudor Child (2013) writes: “An aristocratic two-year-old wears a smock with frilled cuffs under a gown with fashionably wide turnback sleeves and a simplified version of a French hood” (25). The slightly older Charlotte of France (Fig. 3) dresses in an even more fully adult style with a low-cut square bodice like that seen on Françoise de Longwy (Fig. 11) above.

Fig. 1 - Jean Clouet (French, 1480-1541). François III, Dauphin de France, ca. 1520. Oil on panel; 16 x 13 cm (6.2 x 5.1 in). Antwerp: Royal Museum of Fine Arts, inv. nr. 33. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 2 - Jean Clouet (French, 1480-1541). Madeleine of France (1520 - 1537), ca. 1522. Oil on panel; 16.1 x 12.7 cm (6.3 x 5 in). Weiss Gallery. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 3 - Jean Clouet the Younger (French, ca. 1485-1541). Portrait of Charlotte of France, ca. 1522. Oil on cradled panel; 17.78 x 13.34 cm (7 x 5 1/4 in). Minneapolis Institute of Art, 35.7.98. Bequest of John R. Van Derlip in memory of Ethel Morrison Van Derlip. Source: MIA

References:

- “Agnolo Bronzino (1503-72) – Portrait of a Lady in Green.” Accessed June 18, 2019. https://www.rct.uk/collection/405754/portrait-of-a-lady-in-green.

- Ashelford, Jane. A Visual History of Costume: The Sixteenth Century. London: Batsford, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/748457696.

- Boucher, François, Yvonne Deslandres, and John Ross. A History of Costume in the West: With 1188 Illustrations, 365 in Colour. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/443676264.

- Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Cunnington. Handbook of English Costume in the Sixteenth Century. London: Faber and Faber, 1954. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/362761.

- Currie, Elizabeth. Fashion and Masculinity in Renaissance Florence. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1000616867.

- Davenport, Millia. The Book of Costume. New York: Crown Publishers, 1948. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/922657048.

- Hayward, Maria, ed. Dress at the Court of King Henry VIII. Leeds: Maney, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/997437672.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950.

- Huggett, Jane, Ninya Mikhaila, Jane Malcolm-Davies, and Michael Perry. The Tudor Child: Clothing and Culture 1485 to 1625. Hollywood: Quite Specific Media, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/925431430.

- “Portrait of a Young Lady.” Accessed June 10, 2019. https://www.gallery.ca/collection/artwork/portrait-of-a-young-lady.

- “Portrait of Marguerite of Navarre, 13th – 16th Century.” Accessed June 20, 2019. http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/walker/collections/paintings/13c-16c/item.aspx?id=236719.

- Reynolds, Anna. In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/824726826.

- Schwarz, Matthäus, Veit Konrad Schwarz, Ulinka Rublack, Maria Hayward, and Jenny Tiramani. The First Book of Fashion: The Book of Clothes of Matthäus and Veit Konrad Schwarz of Augsburg. London: Bloombury Academic, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/957324375.

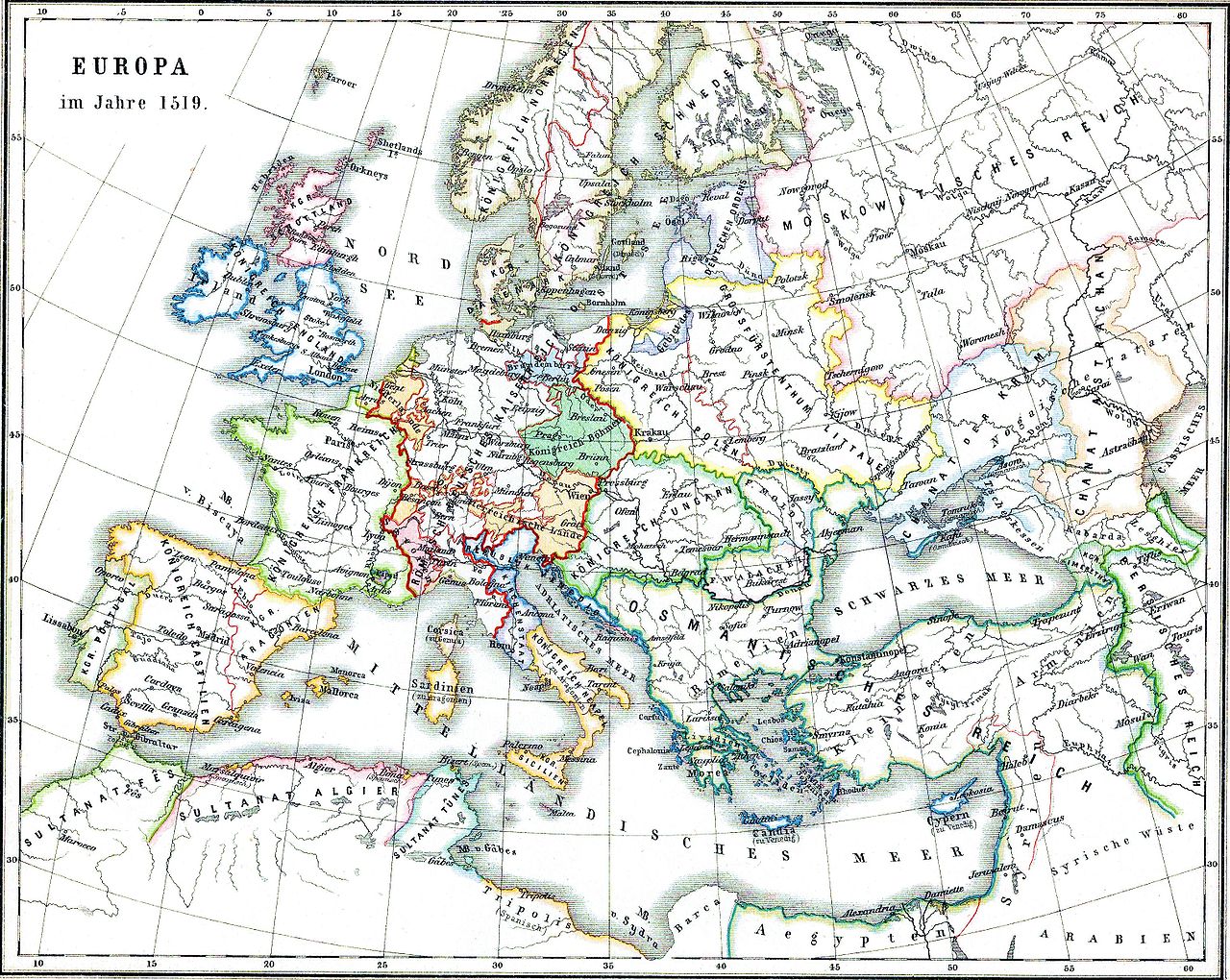

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1520-1529

Rulers:

- France: King Francis I (1515-1547)

- England: King Henry VIII (1509-1547)

- Spain: King Charles V (1516-1556)

Europa 1519. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Events:

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 16th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.