OVERVIEW

During this decade, men’s fashionable dress exhibited few changes from the preceding ten years, apart from the powdered wig that became noticeably less voluminous. For women, the most significant developments were the decline of the fontange, the elaborate wired headdress that had been popular since the 1680s; the increasingly widespread adoption of the hoop-petticoat, or panier; and, around 1716, the introduction of the robe battante, or sack, a billowing gown that replaced the mantua as everyday dress for women in the 1720s.

Following the death of Louis XIV in 1715, his nephew Philippe II, Duc d’Orléans, served as Regent for the five-year-old King Louis XV (1710-1774) until his own death in 1723. The Regency marked a shift away from the heavily regulated etiquette of court life at Versailles to a (relatively) more informal lifestyle in the aristocratic hôtels particuliers and outdoor spaces of Paris, depicted in the paintings of Jean-Antoine Watteau.

Womenswear

For most of this decade, women continued to wear the bustled and trained mantua over a matching or contrasting petticoat (Fig. 1); however, these were the last years during which this two-piece gown was worn as fashionable dress. London newspapers that regularly included notices of thefts or lost items of dress affirm the continued popularity of the mantua during the 1710s. Several of these garments were stolen from the house of “Colonel Blakiston in Broad Street by Golden Square” in December 1714, including “One Green Sattin Mantua imboider’d with Silver; one Crimson Sattin Mantua; a stript Sattin Mantua, Purple and White; a flower’d Callico Mantua,” as well as “Green and Gold Trimming for Petticoats” (Extracts from Notices, n.p.).

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. Two ladies and an officer seated at tea, ca. 1715 (painted). Oil on canvas; 79.5 x 9.25 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, P.51-1962. Bequeathed by Claude D. Rotch. Source: V&A

Although mantuas remained dominant, the robe battante (also known as the robe volante—both terms that suggest a flowing dress) made its first appearance in the second half of the decade, primarily among daring young women. Similar to the mantua, this informal gown was T-shaped, with two full selvage widths front and back, joined on top of the shoulders, where the excess fabric was pleated to form “robings” down the center front and stitched into two box pleats across the shoulder blades. The robe battante, like the mantua, had elbow-length sleeves with winged cuffs. Unlike the mantua, however, the robe battante was not trained or belted at the waist, allowing the pleats to hang loose from the upper back.

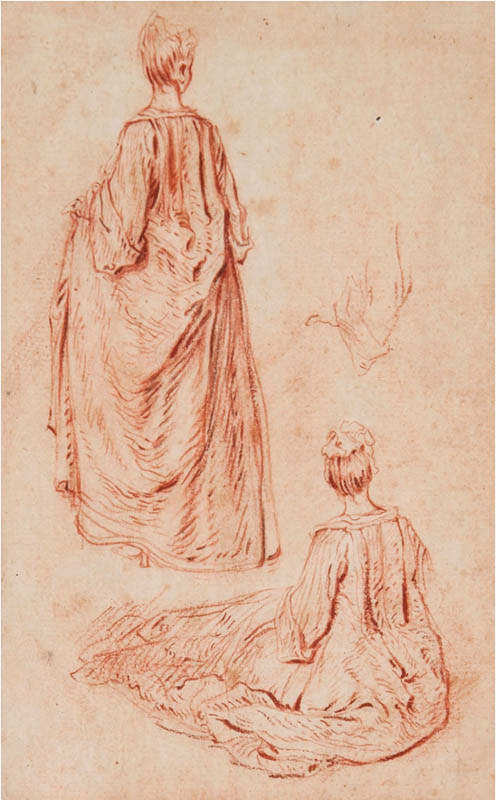

In his paintings and drawings dating from the mid-to-late 1710s, Jean-Antoine Watteau depicted young women, strolling and seated, in billowing, lightweight silk robe battantes (Figs. 2-4). The robe battante’s resemblance to undress was considered indecent by many at the time. In 1718, Elisabeth-Charlotte, Duchesse d’Orléans and the Regent’s mother, attributed the introduction of these gowns to Louis XIV’s long time mistress and mother of his four bastard children, who would later be legitimized:

“It was Madame de Montespan who designed the robe battante to conceal her pregnancies because this style of dress hid her figure. But when she appeared in them it was precisely as if she had publicly announced that which she affected to conceal, for everybody at Court would say: ‘Mme de Montespan has put on her robe battante so she must be pregnant’” (quoted in Waugh/Women 114-15).

Fig. 2 - Antoine Watteau (French, 1684-1721). Detail of Assemblée dans un parc, early 18th century. Oil on panel; 32 x 46 cm. Paris: Louvre Museum, MI1124. Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle. Source: RMN Grand Palais

Fig. 2 - Antoine Watteau (French, 1684-1721). Assemblée dans un parc, early 18th century. Oil on panel; 32 x 46 cm. Paris: Louvre Museum, MI1124. Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle. Source: RMN Grand Palais

Fig. 3 - Antoine Watteau (French, 1684-1721). La Perspective, 1715. Oil on canvas; 46.7 x 55.3 cm. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 25.573. Maria Antoinette Evans Fund. Source: MFA Boston

Fig. 4 - Antoine Watteau (French, 1684-1721). Three Studies of a Woman, Seated and Standing, and Study of a Hand, ca. 1710-1720. Red chalk on paper; 16.5 x 24.8 cm. Stockholm: National Museum of Sweden, NMH 2824/1863. Transferred 1866 from Kongl. Museum. Source: National Museum of Sweden

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. Doll, depicting the nanny as a seamstress, 1715-1730. Chintz, silk, linen, glass, paper, hair, mesh; 18 cm (seated). Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, BK-14656-150. Gift from Mrs. ASM van Tienhoven-Hacke. Source: Rijksmuseum

Fig. 6 - Antoine Trouvain (French, 1656-1708). Mademoiselle d'Armagnac en Robe de Chambre, 1695. Engraving; 27.4 x 19.1 cm. Paris: La Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Source: BNF

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (Dutch). Cambaay, ca. 1710-1730. Painted cotton (chintz), wool, silk. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, BK-NM-13107-A. On loan from Ms. HG Rahusen, Amsterdam. Source: Rijksmuseum

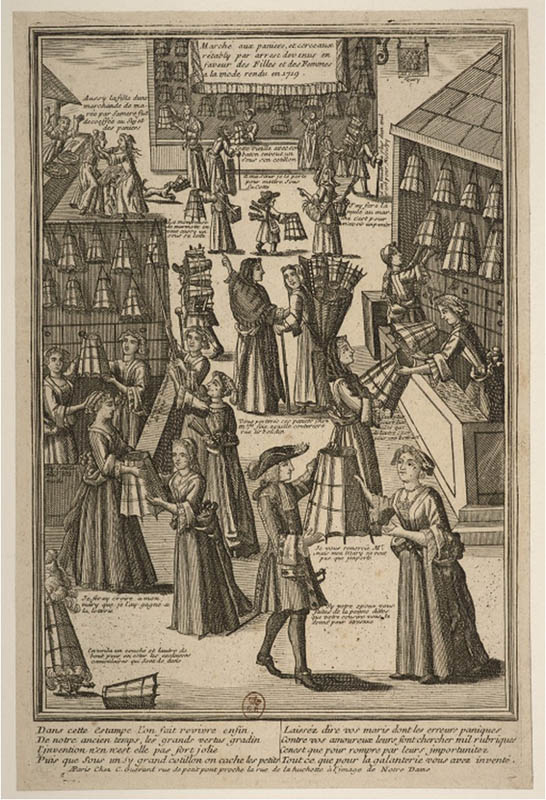

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown. Marché aux paniers et cerceaux, early 18th century. Corbis Historical. Source: Getty Images

Among the mantuas stolen from Colonel Blakiston’s house—presumably the property of one of his female relatives—was one of “flower’d Callico.” Calicoes—painted-and-dyed or printed cottons—for dress and furnishing were introduced to the West from India in the early seventeenth century (Watt 84-87). These colorful and colorfast washable fabrics were increasingly available in a range of qualities and gained widespread popularity among men and women across the socio-economic spectrum throughout the seventeenth and into the early eighteenth centuries (Figs. 5-7). As a result, silk weavers in both France and England protested the importation of Indian cottons that they saw as a threat to their livelihoods. France was the first to enact a ban in October 1686—a decree of the Royal Council of State “prohibited not only the import [into the country] of cotton painted in India but also the production in France of imitations.” Another decree passed in 1691 went further, banning white cotton cloth from India (Brédif 17).

Numerous articles that appeared in English newspapers in 1718 and 1719 chart the escalating tensions around imported Indian cottons that, despite the Calico Act passed by Parliament in 1700, were nonetheless still worn (Eacott 731-32). On August 23, 1718, the Original Weekly Journal reminded readers that:

“all Callicoes painted, dyed, printed or stained there [Persia, China, or East India], are prohibited to be worn, or otherwise used, within this Kingdom,” while simultaneously acknowledging, “that great Quantities of the said Goods are now sold and used in this Kingdom, contrary to the said Act.” (Extracts from Notices, n.p.)

A year later, in July 1719, The Weekly Journal or Saturday’s Post reported an incident that had recently occurred in Norwich in which “a Parcel of Fellows got together in a Mobbish Manner and tore People’s Callico Gowns and Petticoats off their Backs.” The paper also asserted that, “They March in considerable Numbers through the streets…carrying in a triumphing Manner the Callicoes they get upon the Top of Poles…” (Extracts from Notices, n.p.). And, the following month, the Original Weekly Journal recounted that:

“four Persons convicted for riotous Practices among the [silk] Weavers, stood in the Pillory at the Market-Place in Spittle-Fields [the center of the English silk weaving industry in East London]… three Women in Callicoes came in a Hackney-Coach, and drove several times round them, as they imagined, to insult ‘em; but the Weavers, enrag’d at this, stop the Coach, stript them and then sent them home, notwithstanding a Detachment of Guards was there to keep all quiet” (Extracts from Notices, n.p).

These events speak to the determination of the silk weavers to prohibit entirely the wearing of Indian cottons—a campaign in which they were ultimately successful. In March 1721, Parliament passed a second Calico Act that further regulated the consumption of these commodities in Britain, although not in the American colonies (Eacott 732).

Women’s “natural” penchant for fashion and its ever-changing novelties—and the social, economic, gender, and cultural woes that this perceived weakness brought about—was a constant refrain throughout the eighteenth century. In the 1710s, the increasing popularity of the hoop-petticoat, or panier, introduced in England around 1709, resulted in attacks in the press and in visual satire. A French print, Marché aux paniers et cerceaux (Market for paniers and hoops) dated 1719, comments on this form of understructure that had made its way across the Channel (Fig. 8). In a marketplace, women of all ages and social status (most of whom wear mantuas) are examining and—in some cases—purchasing these new fashionable commodities. The woman in the lower right corner indicates to the street seller that her husband would object to her wearing a hoop, to which the merchant replies, “If your husband causes you distress, tell him that your cousin gave it to you as New Year’s gift,” (quoted in Bruna 104), while another shopper tells the vendor that she will present her recent acquisition to her spouse as a lottery winning (Bruna 104).

The hoop was denounced for its size (and, thus, the amount of space that women occupied in public), its inconveniences, its troubling, mechanical nature, and, in particular, its indecency. An address “to the Ladies” published in the Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer on May 9, 1719, averred that the original “Machine” was intended “To hide the Pregnancies of a certain Lady.” The (undoubtedly male) writer declared the hoop “an excellent Invention to break China; crowd Walks, Rooms, Pews, and Coaches” and noted that it exposed “the Sex to the Insults of the Ruder and the Rallies of the more polite sort of mankind.” What “incense[d]” him “above all…is the Immodesty of it” that led women to forget that they were Christians. As he bluntly put it:

“To the Scandal of the Present Age be it spoken, Never were Such secret Discoveries made of the Sex, as by the Hoop Petticoat. The Printing of such Discoveries every Day, with the Names of the Ladies, would, in time, help us to an exact Description of the Legs, Garters, Thighs, &c, of most of the British Ladies” (Extracts from Notices, n.p.).

In “Unhoop the Fair Sex: The Campaign Against the Hoop Petticoat in Eighteen-Century England,” Kimberly Chrisman argues that, “In the face of widespread and violent protest from men, women willingly adopted the hoop as a means of protecting, controlling, and ultimately, liberating female sexuality” (Chrisman 7). The hoop also “acted as a barometer of class tensions” (Chrisman 16). In 1711, The Spectator worried that “the strutting Petticoat smooths all distinctions…Should this fashion get among the ordinary people, our public ways would be so crowded, that we should want street room” (quoted in Chrisman 16). Further, the ambiguity suggested by this new underpetticoat was moral as well as economic: The Spectator complained that the hoop “levels the mother with the daughter; and sets maids and matrons, wives and widows, upon the same bottom” (quoted in Chrisman 20-21).

Next to the body, women of all classes wore a white linen chemise. This T-shaped undergarment with elbow-length sleeves, that remained essentially the same throughout the eighteenth century, protected the outer garments from perspiration and body oils. The fineness of the fabric, the number of shifts in a woman’s wardrobe, and the frequency with which they could be changed corresponded to her wealth. (Styles 79). Upper-class women had multiple shifts of high-quality, expensive white linen, perhaps trimmed with muslin at the neck and sleeves, allowing for a daily renewal of this undergarment; working-class women had fewer shifts that were made from coarser, less expensive types of linen such as flax and hemp that might be washed weekly and would likely remain in their wardrobes far longer than those of wealthy women (Styles 79).

Over the shift, women wore whalebone stays (laced up the center front or center back) that created a rigid inverted cone shape (Waugh 41) (Fig. 1). For women of means, the linen exterior of the stays was often covered with silk, while working-class women’s stays were plain and might even be made of leather (Baumgarten 122). In addition to several gowns that were reported stolen from a house in London by the Daily Courant on September 28, 1715, was “a New Pair of Black Tabby [plain weave silk] Stays, sticht all over” (Extracts from Notices, n.p.)

Under their gown and petticoat, women wore knitted stockings of silk, wool, or cotton in a range of colors including “blue, green, pink, cherry, sky, and scarlet,” secured over the knee with ribbon garters (Cunnington 174), and shoes with long, pointed toes, high curved heels, and latchets that fastened over the instep with buckles or ties (Cunnington 170). The highly feminine appearance of women’s shoes—distinctly different from the heavy form of men’s footwear—was reinforced by their materials that favored woven or embroidered silks, embellished with braid or metal lace (Fig. 9, vs. Fig. 10 in menswear).

In the eighteenth century, women did not carry purses as we know them today. Instead, they placed their small items of value in one, or, more generally, two separate pockets that were tied around the waist with a linen tape over the chemise (Fig. 10). Access to the pockets was through side slits in the outer gown and petticoat and, if one was worn, the hoop. Although entirely concealed from view, these functional accessories could be made of woven silk, embroidered linen (often worked by the wearer), or more serviceable fabrics such as plain sturdy linen. A notice from the Daily Courant lists the contents of a “flower’d Damask Pocket” that was lost “from a Gentle-Woman’s Side” in Grace Church Street one night in February 1718:

“an old Gold Watch, made by F. Stamper, with a Gold Chain and Cornelian Seal, a Bunch of Keys, a Silver Thimble, a Cambrick Handkerchief, a Pair of Spectacles and Case, a silver Toothpick Case, with several other Things of but small Value.” (Extracts from Notices, n.p.)

Along with the mantua that fell out of vogue by the end of this decade, the fontange headdress (with which it had usually been accessorized) also disappeared. In his extensive memoirs detailing life at the French court, Louis de Rouvroy, Duc de Saint-Simon, attributed the sudden fall in popularity of these wired headdresses to the elderly Duchess of Shewsbury, who visited Versailles with her husband in 1713:

“She thought our ladies’ headdress ridiculous, which indeed it was. It was a structure of wire, ribbons, hair and geegaws more than two feet high… The King, in everything else an absolute dictator, could not endure them… and no matter what he said or did, could not get rid of them. What the King could not achieve was accomplished with surprising rapidity by a silly old foreigner. After being so extremely high they then fell extremely low.” (quoted in Waugh/Women 114)

Instead, women began to wear “pinners”—small round caps of fine white linen, with single or double frills and often trimmed with lace or ribbons (Cunnington 156) (Fig. 11). Some pinners were worn with lappets, two long narrow streamers of linen or lace, that could be left hanging or secured onto the crown (Cunnington 156).

Women’s riding habits that, apart from the long, full skirt, took their inspiration from masculine attire continued to draw the ire of social commentators, who decried what they saw as a deliberate and unacceptable form of gender blurring (De Young). In 1714, a writer in The Spectator complained that, “Among the several female extravagancies I have already taken notice of, there is one which still keeps its ground. I mean that of the ladies who dress themselves in a hat and feather, a riding coat and a perriwig, or at least tie up their hair in a bag of ribbon, in imitation of the smarter part of the opposite sex” (quoted in Waugh/Women 114).

Sir Godfrey Kneller’s portrait of Frances Pierrepont, Countess of Mar, dating to 1715, shows her in an elegant riding habit of (impractical) pale pink silk extensively trimmed with silver braid (Fig. 12). Her hair (or wig) worn down over her shoulders, knotted cravat, and three-cornered hat also emulate men’s attire. An advertisement published in the Spectator on June 2, 1711, describes a similar habit that was being offered for sale “at very reasonable Rates” at a shop in Covent Garden: “A Compleat Lady’s Riding Suit of Black Camblet [worsted wool or worsted and silk mixture], well laced with Silver, being a Coat, Wastcoat, Petticoat, Hatt and Feather, never worn but twice” (Extracts from Notices, n.p.). Although hardwearing camlet was generally used for riding habits in the first half of the century, the countess’s silk ensemble denotes her wealth and aristocratic status (Buck 52).

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (English). Pair of shoes, ca. 1710. Leather sole, covered wooden heel, and satin trimmed with silk braid. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.53&A-1940. Given by Alfred Reynolds. Source: V&A

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (English). Pockets, 1700-1725. Linen, hand-sewn with linen thread and embroidered in coloured silks, with silk ribbon and linen tape. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.281&A-1910. Source: V&A

Fig. 11 - Antoine Watteau (French, 1684-1721). A Seated Woman, 1716. Red chalk on paper. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 12 - Godfrey Knller (English, 1646-1723). Frances, Daughter of Evelyn Pierpont, 1st Duke of Kingston, early 18th century. Oil on canvas; 233 x 142 cm. Alloa: National Trust for Scotland, Alloa Tower, 97.7.5. on loan from the Earl of Mar and Kellie. Source: Art UK

Fashion Icon: LOUISE-BÉNÉDICTE DE BOURBON-CONDÉ (1676-1753)

Fig. 1 - Nicolas de L'Armessin II (French, 1645-1725). Portrait of Louise-Benedicte de Bourbon, Duchess of Maine, late 17th century. Engraving. Paris: La Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Source: BNF

In 1700, the duchesse left Versailles and took up residence at the chateau of Sceaux, about eight miles southwest of Paris (Lewallen 8). There, she “established her own court” and created “a fantasy world” in which she reigned supreme, acclaimed in “numerous poems, songs, and plays…as Princess, Queen, and Goddess” (Lewallen 8). One of the many “roles” that the duchesse adopted at Sceaux was that of Queen of a “mock chivalric” order, “The Order of the Honeybee,” with the title, “la grande Ludovise, Dictactrice Perpetuelle de l’Ordre (“The Great Louise, Dictator in Perpetuity of the Order” (Lewallen 8-9).

Late seventeenth-century engravings of the Duchesse show her in the three main types of dress worn by aristocratic women: a formal grand habit that was required at court (Fig. 2); a more informal but, appropriately, luxurious mantua of brilliant red silk mantua edged with gold worn over a blue silk petticoat trimmed with a deep band of brocaded silk as well as jewels on the stomacher and a fontange headdress (Fig. 3); and seated at her toilette in a loose fitting robe de chambre with a cascading train (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. Madame la Duchesse du Maine, on foot, late 17th century. Engraving. Paris: La Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Source: BNF

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Louise Bendedicte de Bourbon, 1692. Engraving. Corbis Historical. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Portrait of A. L. B. de Bourbon, Duchesse du Maine, on foot, early 18th century. Engraving. Paris: La Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Source: BNF

The Duchesse du Maine relentlessly asserted her royal blood through patronage of the arts, including architecture and interior decoration (in particular, of the Hôtel du Maine in Paris), painting, and spectacular theatrical performances held at Sceaux, all of which enabled her to enact multiple roles. An account of the official visit of the papal nuncio in 1732 to the Duchesse’s chambre de parade at her Paris hôtel particulier evokes the image of a monarch and illustrates her brilliant use of etiquette to buttress her status:

“All attention was now focused on the duchesse du Maine, reclining on the bed to receive her guest. Permitted behind the balustrade, the ambassador was acknowledged for his status by the offering of an armchair. Louise-Bénédicte’s many ladies-in-waiting were allowed the tabouret, but were seated outside the privileged zone of the ruelle [the area next to the bed]. They were instead spectators of the action on the stage delimited by the balustrade. At the center, on the throne-like lit de parade, the duchess played her role as princess in the spectacle of courtly display.” (quoted in Lewallen 16-17)

The duchesse further extended her self-serving role playing in paintings that she commissioned from leading artists: François de Troy depicted her as Queen Dido of Carthage in his large-scale canvas, The Feast of Dido and Aeneas (ca. 1702) (Fig. 5), and as the Egyptian pharaoh Cleopatra in a half-length portrait (Fig. 6), and Nicolas de Largillière presented her as Pomona, the Roman goddess of abundance (Lewallen 8). Among the stage roles played by the Duchesse du Maine were Iphigenia in Euripdes’ play Iphigenia in Aulis, Finemouche in Nicolas de Malézieu’s Tarentole, and characters from Molière’s Les Femmes Savantes and L’Avare (Lewallen 8). Although many courtiers were eager to attend these performances, the Duc de Saint-Simon mocked the Duchesse’s passion for “dressing up as an actress, learning and spouting the leading roles, and devoting [herself] to a public spectacle on the stage” (quoted in Lewallen 8).

Yet another role of which the Duchesse was proud was that of a femme savante. Like most young noblewomen, she was not highly educated, but her marriage allowed her the independence to actively pursue her intellectual interests and she filled her numerous, private cabinets with books on history, law, and mathematics and studied with leading thinkers of the day (Lewallen 23). The Astrononomy Lesson of the Duchesse du Maine by François de Troy (Fig. 7) presents Louise-Bénédicte in a white silk gown and blue velvet robe highlighted with gold and her mathematics tutor, Nicolas de Malézieu, dressed in classicizing garments, seated at a table with an open book and armillary sphere.

Masquerade balls—that provided another opportunity for role playing—were a favorite form of entertainment for the duchesse. Beginning in 1705 and continuing to 1743, she hosted lavish evening entertainments at her chateau, known as Les Grandes Nuits de Sceaux. Supervised by preeminent composers, musicians, and literary figures such as Voltaire, these included masquerade balls, musical, dance, and theatrical performances, and elaborate fireworks. An engraving from about 1695 shows Louise-Bénédicte in a mantua with flounces of heavy, scalloped fringe, a lace fontange and cravat à la Steinkirk, holding a black oval mask (Fig. 8).

Following the death of Louis XIV in 1715, the Duc and Duchesse du Maine were involved in a plot to oust the Duc d’Orléans as regent, a treasonous act for which they were both exiled for a year from 1719 to 1720 (Lewallen 5). At the end of her exile, the Duchesse returned to Sceaux and to her new hôtel particulier in the aristocratic faubourg Saint-Germain neighborhood of Paris, where she resumed her former extravagant lifestyle and patronage of the arts that served to convey—and, in some instances, significantly exalt—her reputation and her status at court (Lewallen 10).

Fig. 5 - François de Troy (French, 1645-1730). The Feast of Dido and Aeneas: An Allegorical Portrait of the Family of the Duc and Duchesse du Maine, 1704. Oil on canvas; 160.5 x 202.5 cm. Private collection. Source: Sotheby's

Fig. 6 - François de Troy (French, 1645-1730). The Duchess of Maine depicted as Cleopatra, ca. 1690. Oil on canvas; 50 x 39 cm. Versailles: Chateau de Versailles, ber MV 8288. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 7 - François de Troy (French, 1645-1730). Nicolas de Malézieu enseignant l'astronomie à la duchesse du Maine, ca. 1705. Oil on canvas; 97.5 x 130 cm. Source: Artnet

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown. Louise Bénédicte de Bourbon, duchesse du Maine, early 18th century. Engraving. Paris: La Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Source: Studies in the Decorative Arts

Menswear

Fig. 1 - André Bouys (French, 1656-1740). La Barre and Other Musicians, about 1710. Oil on canvas; 160 x 127 cm. London: The National Gallery, NG2081. Bought, 1907. Source: The National Gallery

A portrait by André Bouys, dating to about 1710, depicts four chamber musicians to Louis XIV: the French flautist and composer Michel de La Barre (second from the right), the violist Antoine Forqueray, and two of the Hotteterre brothers, who were also flautists (Fig. 1/ Caude et al.). The cut, fabric, and trimming of their three-piece suits are very similar to those of the first decade of the century. The coats feature round necklines, center-front button closures, loose-fitting sleeves with wide cuffs ornamented with decorative buttons, full skirts pleated at the sides, deep scalloped pocket flaps, and metal thread embellishment. The waistcoat of one of the Hotteterre brothers is a few inches shorter than his coat, and all but conceals his breeches. All five men wear solid-colored wool suits in shades of brown, taupe, grey, and blue. Turning the pages of one of his composition books, La Barre appears to be wearing a suit in which all three pieces match; the edges of his waistcoat, barely visible underneath his coat that is open to just below the waist, are trimmed with silver as are his coat fronts, sleeve cuffs, and pockets. The Hotteterre brother, however, has left his coat with gold-trimmed buttonholes open, revealing his contrasting waistcoat extensively woven with metal thread.

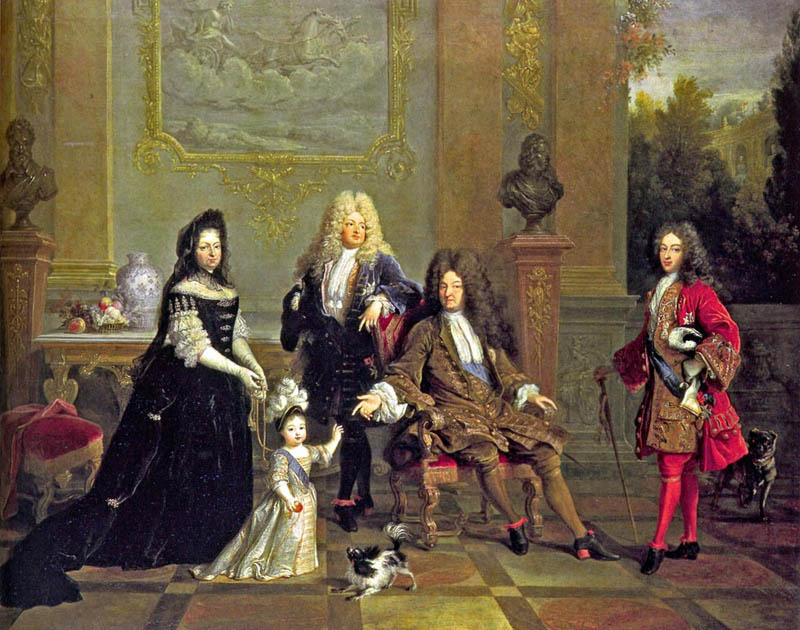

For formal wear, plain or embroidered silk velvet and heavily embellished wool were appropriate. In his portrait by Alexis-Simon Belle, Matthew Prior, the English ambassador to the court of Louis XIV, wears a soft brown wool coat with the center front edges, cuffs, and full skirts covered with a dense floral pattern worked in gold thread (Fig. 2). A posthumous portrait of Louis XIV and his heirs shows the king, his son, known as Monseigneur, and his grandson, the Duc de Bourgogne, in silk velvet suits of lustrous brown, deep blue, and scarlet, respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 - Alexis-Simon Belle (French, 1674-1734). Matthew Prior (1664-1721), Fellow, Ambassador to France, 1713-1714. Oil on canvas; 90.2 x 69.8 cm. Cambridge: St John's College, University of Cambridge, 10. gift from or bequeathed by the sitter, 1718–1721. Source: Art UK

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (French). Madame de Ventadour with Louis XIV and his Heirs, 1715-1720. Oil on canvas; 127.6 x 161 cm. London: The Wallace Collection, P122. Source: The Wallace Collection

Fig. 4 - Sir Godfrey Kneller (English, 1646-1723). Sir Christopher Wren, 1711. Oil on canvas; 124.5 x 100.3 cm. London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 113. Purchased, 1860. Source: NPG

Fig. 5 - Alexis-Simon Belle (French, 1674-1734). Portrait of an Unknown Man, ca. 1712. Oil on canvas; 134.5 x 102 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, P.12-1978. Purchased at Sotheby's London, 19 July 1978, lot 33, at the instigation of the Textiles department. Source: V&A

Fig. 6 - Amoy Chinqua (Chinese). Figure of a European Merchant, 1719. Polychrome unfired clay and wood; 32.9 x 14.1 x 13.7 cm. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014.569. Purchase, Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest and several members of The Chairman's Council Gifts, 2014. Source: The Met

The renowned architect Sir Christopher Wren chose an aubergine-colored velvet suit set off with gold-thread buttons and buttonholes when he was painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller for his portrait in 1711—the year in which he completed St. Paul’s Cathedral (Fig. 4).

In silk design, the “luxurious or transitional” phase was in vogue between 1713 and 1719 (Rothstein 40). Alexis-Simon Belle’s portrait of an unidentified man wearing a magnificent waistcoat with a gold ground brocaded with polychrome silk florals and foliage, dating about 1712-13, illustrates one of these densely patterned silks (Fig. 5). The same silk is used for the cuffs of the sitter’s otherwise plain, fawn-colored wool suit embellished with gold metal thread buttons and long buttonholes, also worked in gold thread. Although such elaborately patterned silks would not have been used for the coat or breeches, they were appropriate—and eye-catching—for waistcoats (Fig. 6). Specialized weavers created these top-of-the-line fabrics that took weeks to complete, with just a few inches woven each day. Given the time and financial investment involved in their creation as well as the regular changes in fashionable silks, only a few lengths were produced. Natalie Rothstein noted that, “Goods as intrinsically expensive as woven silks were not produced for stock, but to order and in limited quantities” (Rothstein 22).

Adding to the opulence of the sitter’s waistcoat in Belle’s portrait is the heavy gold fringe adorning the lower center front opening and the hem (Fig. 5). In Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe, Aileen Ribeiro indicates that “Court waistcoats were sometimes decorated with fringes of silk, silver, and gold thread and chenille in the first third of the eighteenth century” (Ribeiro 21). A notice in the London Gazette on November 17, 1713, described “A Silver Brocade Wastcoat trim’d with a Knotted Fringe and lin’d with White Silk,” and on February 17, 1715, the Post Man reported the theft of a number of male garments and accessories including “a fine Cinnamon Cloth Suit with Plate Buttons, the Wastecoat fringed with a Silk Fringe of the same Colour” (Extracts from Notices, n.p.).

Similar to the women’s shift, men wore a white linen T-shaped shirt as their primary undergarment and, like its female counterpart, the quality and the number of shirts owned by the wearer, that could be plain or decorated with muslin or lace ruffles at the chest and wrists, depended on his wealth (Fig. 7). Throughout this decade, the shirt was accessorized with the cravat, a long rectangular piece of linen tied around the neck with the two ends hanging over the chest (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4) or twisted and secured in one of the waistcoat buttonholes, a style known as a Steinkirk that was introduced in 1692 (Figs. 3, 8, 9). Cravat ends could be left plain or knotted (Figs. 1, 4, 9) or trimmed with delicate lace (Figs. 2, 5, 8), that often matched the shirt cuffs. On November 17, 1713, the Post Boy reported the loss of “four fine Holland [linen] Shirts, the Wrist-bands and Slits of the sleeves laced with fine Macklin [Mechlin, a Flemish bobbin lace]; and one plain one,” and among the contents of a trunk stolen in early January 1719 were “2 Dozen of Shirts, some with laced Ruffles, [and] 13 Cravats” (Post Man, January 17, 1719).

As in the previous decade, men wore their stockings rolled over the knee band of the breeches (Figs. 1, 3, 6) and knitted silk or wool hose that matched the suit were a point of fashion. Two of the sitters in Bouys’s group portrait, who each present a shapely leg to the viewer, wear stockings the same color as their suits, and Louis XIV and the Duc de Bourgogne wear stockings that match their brown and red velvet suits, respectively, and (Figs. 1, 3). On November 17, 1713, the London Gazette notified its readers that “the following Particulars were taken from a Gentleman’s House in Leicester-fields,” including “a Dove-Coloured Cloth Suit embroider’d with Silver, and a pair of Silk Stockings of the same colour” (Extracts from Notices, n.p.).

Fig. 7 - Nicolas de Largillierre (French, 1656-1746). The sculptor René Fremin in his studio, ca. 1713. Oil on canvas; 135.5 x 109.2 cm. Berlin: Berlin State Museums, 80.1. 1979 Acquired from Agnews art dealer, London. Source: SMB

Fig. 8 - Nicolas de Largillierre (French, 1656-1746). François-Marie Arouet known as Voltaire, writer (1694-1778), 1724-1725. Oil on canvas; 81 x 65 cm. Versailles: Chateau de Versailles, MV 8159. Source: Chateau de Versailles

Fig. 9 - Nicolas de Largillierre (French, 1656-1746). Pierre-Joseph Titon de Cogny, ca. 1715. Oil on canvas. Source: Pinterest

Men’s leather shoes remained blocky in their overall shape with blunt square toes and thick heels (Fig. 10).

By about 1715, the oversized full-bottomed wig began to go out of favor among fashionable men (Ribeiro 28) (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 7, 9). Other, less voluminous styles came into vogue, such as the campaign wig, “encouraged by the military campaigns of the War of the Spanish Succession” (Ribeiro 28). The sitter in Belle’s portrait (Fig. 5) wears this newly fashionable wig, characterized by two locks tied at the ends that fell over each shoulder and a third that hung down the back (Ribeiro 28). Powdering the wig was optional, according to the wearer’s preferences (Figs. 1-5, 7-9). On July 16, 1715, the Daily Courant alerted readers to a robbery at a house near Croydon, Surrey, from which were stolen “a full-bottom Perriwig, and 3 Campaine Perriwigs” (Extracts from Notices, n.p). As in the previous decade, black three-cornered hats (usually carried under the arm), swords, and canes remained integral elements of a fashionable man’s ensemble (Figs. 3, 8).

In the morning before dressing or when relaxing or working at home, men often wore informal garments known as nightgowns, morning gowns, or banyans (Cunnington 73). Morning gowns and nightgowns were generously cut T-shapes, whereas banyans were more fitted to the body and fastened, single- or double-breasted, across the chest with buttons or froggings (Cunnington 73). Throughout the eighteenth century, many men sat for their portraits wearing this type of elegant “undress” that denoted wealth, status, and an affinity for—or professional engagement with—literary or artistic pursuits. The well-known English writer Jonathan Swift wears a simple yet refined blue silk morning gown over a black velvet waistcoat and breeches in his portrait by Thomas Jervas (Fig. 11).

Although most men and women had their clothes custom made during the eighteenth century, morning gowns that required little fitting were available ready-made from the early decades. On January 18, 1710, the Examiner published a notice announcing what amounted to a closing sale of these gowns for men (and women):

“of all sizes… at very low Rates… large Gowns, Sattins of both sides, at 50 Shillings per Gown, and all other Sort of half Silks, Calimancoes [wool and silk] and Stuffs [wool], made of extraordinary Goods in their several Kinds, proportionately as Cheap, the price being fixed on each, which all Buyers may be convinced is 15 per Cent Cheaper than usual…” (Extracts from Notices, n. p.)

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown. Pair of men's shoes, 1710-1720. Leather, metal, wood, glass, red paint. Utrecht: Centraal Museum, 7950 / 001-002. gift 2013 (On loan since 1937). Source: Centraal Museum

Fig. 11 - Charles Jervas (Irish, 1675-1739). Jonathan Swift, ca. 1718. Oil on canvas; 123.2 x 97.2 cm. London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 278. Purchased, 1869. Source: NPG

CHILDREN’S WEAR

(by Summer Lee)

Leading into the eighteenth century, attitudes about childhood were changing (Nunn 98). This shift was sparked by new philosophies emerging from the Age of Enlightenment. For example, in his 1693 publication, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, John Locke challenged long-held beliefs about best practices for child-rearing.

However, that was not reflected in children’s wear of the first half of the century. In the 1710s, traditions for children’s wear were not unlike those of the previous decade — or the previous century.

Infants were swaddled, as was the long-held European tradition (Tortora and Marcketti). Swaddling was the practice of tightly binding an infants’ limbs, so as to immobilize them (Callahan). The Victoria and Albert Museum possesses a finely embroidered swaddling band dated circa 1700-1750 (Fig. 1). Its elaborate floral embroidery indicates that this was a fashionable “outer swaddling band” (Victoria and Albert Museum).

In the early eighteenth century, babies typically outgrew the swaddling phase between two and four months (Callahan). They were then dressed in “slips” or “long clothes” (Callahan). These were ensembles with a fitted bodice and a very long, full skirt (Fig. 2) (Nunn 99). Babies also wore tight-fitting caps on their heads.

Once a child was becoming mobile, they transitioned into “short clothes” (Callahan). These ensembles allowed for greater mobility because skirts were cut at the ankle (Callahan). Bodices opened at the back and were boned or otherwise stiffened (Callahan). At this phase, toddlers typically had “leading strings” attached to the back of their bodice (Magidson). Leading strings were streamers of fabric used to protect young children from falling or wandering off (“Childhood”).

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (French). Swaddling band, 1700-1750. Hand embroidered linen; 340.5 cm x 12.5 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, B.13-2001. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 2 - Mary Beale (English, 1633-1699). Portrait of a Baby, 1690-1730. Oil on canvas; 77.5 cm x 65 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, B.447-1994. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

When boys were deemed mature enough, they underwent a rite of passage known as “breeching” (Reinier). Breeching referred to the first time a boy wore bifurcated breeches or trousers, symbolizing his entrance into manhood. In the first half of the eighteenth century, boys were typically breeched between the ages of four and seven (Callahan). From that point on, boys during this time followed menswear fashions.

This is demonstrated in portraiture of the time. An American portrait circa 1710 depicts eight-year-old Henry Darnall III in fashionable masculine finery (Fig. 3). Standing behind Darnall is an enslaved African boy wearing a modest coat and a metal collar — “a symbol of servitude reminiscent of the shackles that constrained slaves during their voyage from Africa” (Roark 2003, 73). It should be noted that this is the earliest known depiction of an enslaved African in American painting (Roark 2014, 391). A British double portrait from eight years later also depicts five-year-old Edward Harpur in a menswear ensemble (Fig. 4).

Girls, however, did not fully transition into adult dress until their early teens. As girls aged, elements of fashionable womenswear were incorporated into their dress. An American portrait circa 1710 depicts six-year-old Eleanor Darnall wearing an ensemble that resembles fashionable woman’s Mantua (Fig. 5). However, the ensemble includes characteristics unique to childhood dress: Eleanor’s bodice is back-opening and she wears a white apron. This also applies to Catherine Harpur’s ensemble in the British double portrait circa 1718, although her age is unknown (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3 - Justus Engelhardt Kühn (German). Henry Darnall III (1702-ca.1787), ca. 1710. Oil on canvas; 137.4 x 112.2 cm. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1912.1.3. Source: Marland Historical Society

Fig. 4 - John Verelst (Dutch, 1648-1734). Edward Harpur (1713 – 1761) and his Sister Catherine Harpur, later Lady Gough (d.1740) as Children, 1718. Oil on canvas; 142 cm x 112 cm. Derbyshire: Calke Abbey, NT 290279. Source: National Trust Collections

Fig. 5 - Justus Engelhardt Kühn (German). Eleanor Darnall (1704-1796), ca. 1710. Oil on canvas; 137.79 x 111.79 cm. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1912.1.5. Source: Maryland Historical Society

References:

- Ashton, John. Social Life in the Reign of Queen Anne, taken from original sources. London: Chatto & Windus, 1882 https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000312255

- Baumgarten, Linda. What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothes in Colonial and Federal America. New Haven & London: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in Association with Yale University Press, 2002 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1126360065.

- Brédif, Josette. Classic Printed Textiles from France, 1760-1843: Toiles de Jouy. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/990693498.

- Bruna, Denis. “Early 18th Century Paniers in Contemporary Sources.” In Structuring Fashion: Foundation Garments through History, edited by Frank Matthias Kammel and Johannes Pietsch, 101-107. Munich: Bayerisches Nationalmuseum; Munich: Hirmer, 2019 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1129699413.

- Buck, Anne. Dress in Eighteenth-Century England. London: B. T. Batsford, 1979 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/271451083.

- Callahan, Colleen R. “Children’s Clothing.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed August 08, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0003223.

- Caude, Élisabeth, Jérôme de la Gorce and Béatrix Saule. Fêtes et Divertissements à la Cour. Paris: Gallimard; Versailles: Château de Versailles, 2016 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/968157809.

- “Childhood.” In European Renaissance and Reformation, 1350-1600, edited by Norman J. Wilson, 319-321. Vol. 1 of World Eras. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2001. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3034600137/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=480f4328.

- Chrisman, Kimberly. “Unhoop the Fair Sex: The Campaign Against the Hoop Petticoat in Eighteenth-Century England.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, Vol. 30, No 1 (Fall 1996): 5-23 http://www.jstor.com/stable/30053852.

- Cunnington, C. Willett. Handbook of English Costume in the Eighteenth Century. London: Faber, 1972 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/731183615.

- De Marly, Diana. Louis XIV & Versailles. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1987 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/17917145.

- De Young, Justine. “1680-1689.” Fashion History Timeline. FIT, August 18, 2020. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1680-1689/

- Eacott, Jonathan P. “The Calico Acts, the Atlantic Colonies, and the Structure of the British Empire.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 69, No. 4 (October 2012): 731-762 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5186513692.

- Extracts from Notices which appeared in London Newspapers referring to Objects of Fine and Decorative Arts. From the Burney Collection of Papers in the British Museum. 1937 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/83526007.

- “Introduction to 18th-Century Fashion.” Victoria and Albert Museum, January 25, 2011. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/i/introduction-to-18th-century-fashion/.

- Levey, Santina. Lace: A History. London: Victoria & Albert Museum; Leeds: W.S. Maney, 1983 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/874134825.

- Lewallen, Nina. “Architecture and Performance at the Hôtel du Maine in Eighteenth-Century Paris.” Studies in the Decorative Arts, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Fall-Winter 2009-2010): 2-32 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5556773605.

- Magidson, Phyllis. “Fashion.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 344-348. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3402800166/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=0084684d.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art “Alexis-Simon Belle | Matthew Prior | 1713-14” https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/699753.

- The National Portrait Gallery. “Sir Godfrey Kneller | Sir Christopher Wren | 1711” https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw06939/Sir-Christopher-Wren?LinkID=mp04934&role=sit&rNo=0.

- Nunn, Joan. Fashion in Costume 1200-2000. Bridgewater, NJ: Distributed by Paw Prints/Baker & Taylor, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/232125801

- Orléans, Elisabeth Charlotte, duchesse d’, 1652-1722. A Woman’s Life in the Court of the Sun King: Letters of Liselotte von der Pfalz, Elisabeth Charlotte, Duchesse d’Orleans, 1652-1722. Trans. Elborg Forster. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/968168997.

- Pratt, Lucy, and Linda Woolley. Shoes. London: V & A Publications, 1999 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/963446693.

- Reinier, Jacqueline S. “Breeching.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 118. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3402800074/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=360a7a45.

- Ribeiro, Aileen. Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1171837408.

- Roark, Elisabeth Louise. Artists of Colonial America. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/302384812

- Roark, Elisabeth L. “Keeping the Faith: The Catholic Context and Content of Justus Engelhardt Kühn’s Portrait of Eleanor Darnall, Ca. 1710.” The Journal of the Maryland Historical Society 109, no. 4 (Winter 2014): 391-427. https://www.mdhs.org/sites/default/files/MHMWinter2014.pdf

- Rothstein, Natalie. Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Boston: Little, Brown, 1990 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/21483608.

- Styles, John. The Dress of the People: Everyday Fashion in Eighteenth-Century England. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/615224941.

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Sara B. Marcketti. “The Eighteenth Century 1700–1790.” In Survey of Historic Costume, 266–297. New York: Fairchild Books, 2015. Accessed August 07, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501304194.ch-010.

- Victoria and Albert Museum. “Swaddling Band.” V&A Collections. Accessed August 08, 2020. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O62960/swaddling-band/.

- Watt, Melinda. “‘Whims and Fancies’: Europeans Respond to Textiles from the East.” In Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, edited by Amelia Peck, 82-103. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013 http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/834961134.

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927414537.

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600-1930. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1074444804.

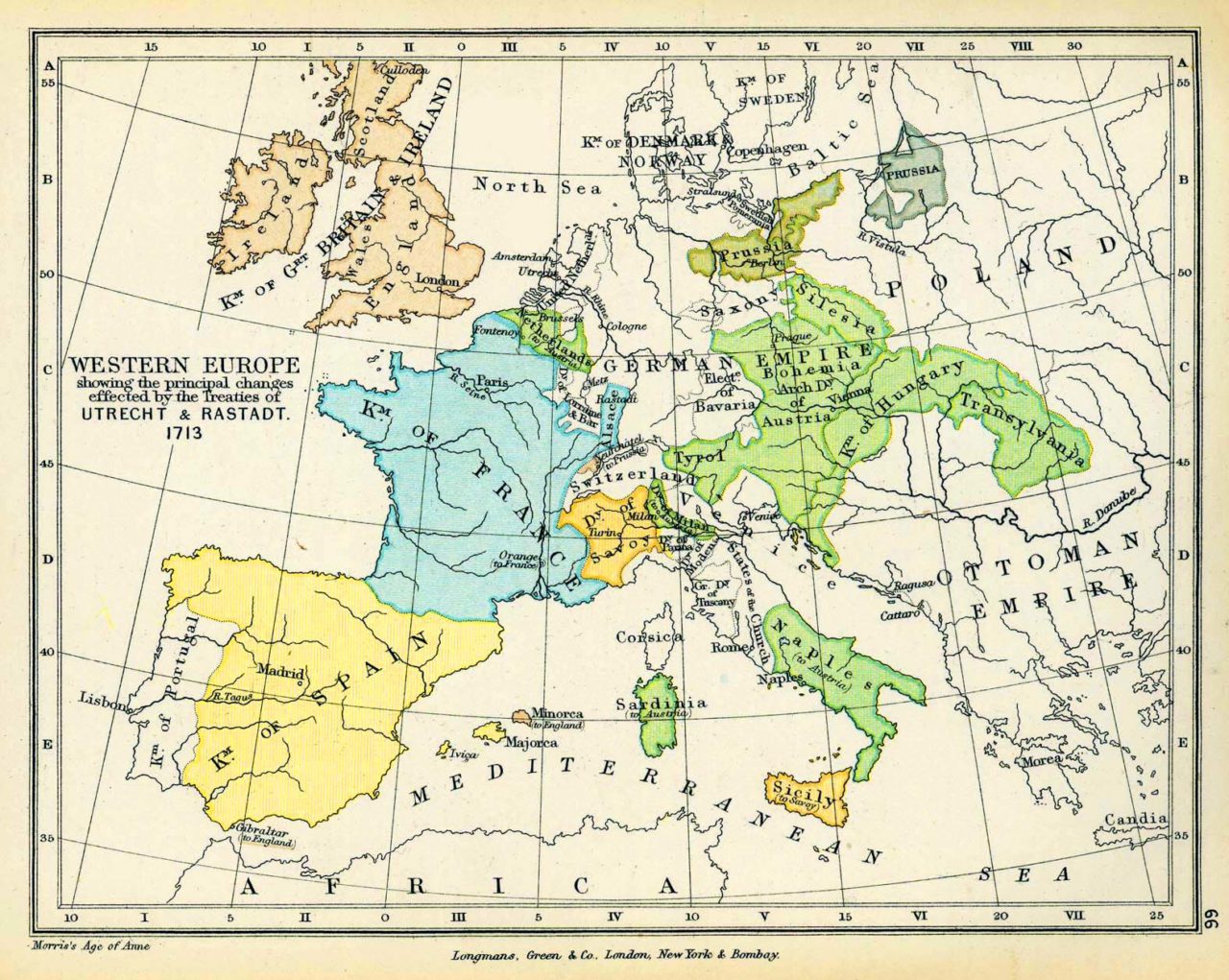

Historical Context

Europe in 1713. Source: emersonkent.com

Events:

- 1711 – Pompeii discovered

- 1717 – Watteau’s Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 18th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.