OVERVIEW

In the 1780s the styles from the previous decade continued to be popularized, emphasizing more casual clothing in both womenswear and menswear. At the same time, fashion publications were becoming a vital part of spreading trends and fashion news.

The informal styles for men and women that were introduced in the previous decade were firmly entrenched by 1780s. For the former, the frock coat with a high turned-down collar and wide lapels, hip-length sleeveless waistcoat, and breeches that outlined the shape of the thighs dominated men’s daytime wardrobes. For the latter, in addition to the robe à l’anglaise, robe à la polonaise, robe à la lévite, robe à la circassienne, and caraco-and-petticoat combination that gained popularity in the 1770s, the robe à la turque, the redingote (the Gallicization of “riding coat”), and the chemise were new options for daywear. A more regular fashion press that emerged in the 1770s continued to expand, disseminating new styles more rapidly to a wider audience.

Womenswear

Apart from the chemise, the various styles referred to above were open robes worn over matching or contrasting petticoats and characterized by a fitted bodice that closed at the center front, usually with hooks and eyes or concealed lacing (Figs. 1-5). The shaped pattern pieces were sometimes lightly boned at the center front and center back seams, ensuring a smooth line (Figs. 1-3, 5). In the preceding decade, the center back panels of the robe à l’anglaise were stitched down as far as the waist and released below to create the fashionable fullness of the skirt (see 1770-1779 overview); in the 1780s, the tightly pleated skirt was cut separately from the bodice, which ended in a pronounced V at the center back waist, accentuating the curve of the lower spine (Figs. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6). As in the 1770s, the preferred fabrics for women’s daytime garments were plain or minimally patterned lightweight silks—stripes of even width were especially in vogue—and cottons that were more suitable to gowns with close-fitting bodices and finely pleated skirts (Figs. 1-6).

In Adelaïde Labille-Guiard’s monumental Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Mademoiselle Gabrielle Capet and Mademoiselle Carreaux de Rosemonde (Fig. 7), exhibited at the Salon of 1785, the artist, who two years earlier was one of the few women to be admitted to the Académie Royale de peinture et de sculpture,

“presented herself to a large and diverse Parisian audience as a protean figure, not only as an ambitious portraitist but also in the guise of a fashionable sitter.” (Auricchio 45)

Seated at her easel, brushes in hand, Labille-Guiard wears a luminous pale blue satin robe à l’anglaise, lined in white silk, with a matching petticoat with one visible seam along her left leg. Ruffles of delicate floral-and-foliate patterned lace and white silk bows decorate the low wide neckline typical of the 1780s and the cuffs of her tight-fitting, elbow-length sleeves. Behind her, Mademoiselle Capet also wears a robe à l’anglaise of soft brown silk taffeta accessorized with a sheer white bonnet, fichu, and sleeve ruffles with matching silk ribbons, while Mademoiselle Carreaux de Rosemonde has sensibly covered her dress with a white linen or cotton smock to protect it from her oil paints.

In her reading of this painting, art historian Laura Auricchio draws attention to Labille-Guiard’s skill at depicting “a dizzying array of materials” including “the shine of satin, the intricacy of lace, the delicacy of feathers… the deep shadows of plush velvet… the porcelain texture of flawless skin” and the “cornucopia of visual treats,” including Labille-Guiard herself in her stylish and highly impractical dress (50). The artist’s flirtatious presentation of her “elaborately clothed but voluptuously revealed body” is closely allied to “another form of commercial imagery associated with women—the fashion plate” (51). Auricchio suggests that two 1784 plates from the Galerie des Modes (Fig. 8) may have provided inspiration for the artist (51). Labille-Guiard thus “simultaneously demonstrated that she possessed the skills required of a portraitist… [and] declared an affinity with the world of trade that was forbidden to academicians and to well-bred women alike” (Auricchio 51).

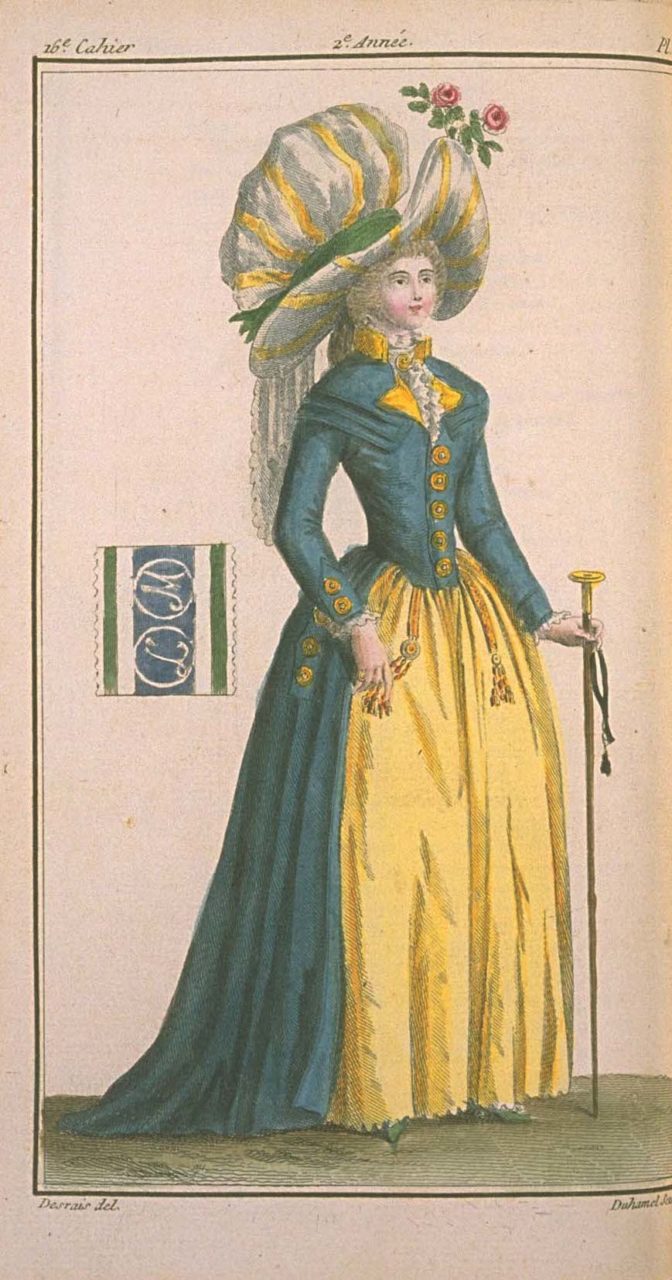

Fig. 1 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Page from Gallerie des modes, 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 x 16 cm. Paris: National Library of France. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à l'Anglaise, ca. 1785-87. Silk. New York: The Metopolitan Museum of Art, C.I.66.39a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1966. Source: The Met

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à l'Anglaise (detail), ca. 1785-87. Silk. New York: The Metopolitan Museum of Art, C.I.66.39a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1966. Source: The Met

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (French). Robe à la Turque, Nov 1, 1786. Engraving. Tokyo: Bunka Gauken University Library, SB00002310. Source: Bunka Gauken

Fig. 5 - Joshua Reynolds (British, 1723-1792). Selina, Lady Skipwith, 1787. Oil on canvas; 128.3 x 102.2 cm. New York: The Frick Collection, 1906.1.102. Henry Clay Frick Bequest. Source: The Frick

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (British). Gown, ca. 1780. Cotton, resist- and mordant-dyed, block-printed, painted and lined. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.217-1992. Source: V&A

Fig. 7 - Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (French, 1749-1803). Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Marie Gabrielle Capet (1761–1818) and Marie Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond (died 1788), 1785. Oil on canvas; 210.8 x 151.1 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 53.225.5. Gift of Julia A. Berwind, 1953. Source: The Met

Fig. 8 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Plate from the Galerie des Modes, 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 x 16 cm. Paris: National Library of France. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown (French). Redingote Magasin des modes nouvelles, April 20 1787. Engraving. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen Library, 070379307. Source: Bunka Gakuen

Although women had worn masculine-inspired wool riding habits throughout the eighteenth century, in the 1780s the redingote constituted fashionable day attire (Fig. 9). This coat dress was also based on menswear with a high collar, wide lapels, and double-breasted closure with outsized buttons, and was often accessorized with paired watch fobs (Fig. 9)—another nod to a current fad among stylish young men. Few redingotes have survived, but their popularity in this decade is evident in the pages of the Galerie des Modes (1778-1787) and the Cabinet des Modes that began publication in 1785 and changed names twice before ceasing in 1793. In November 1786, the retitled Magasin des Modes Nouvelles françaises et anglaises illustrated a young woman in a redingote of “lemon-yellow wool, with apple-green stripes” with a collar and lapels à la marinière (sailor) and a double-tiered “ample gauze fichu” with its ends knotted “en cravatte” (Fig. 10). Barely visible under the hem of her mannish garment are her highly feminine shoes of pink satin trimmed with a black silk ribbon (Fig. 10). At the end of the two-page description that provides further details of her ensemble, “frizzed” coiffure, and “chapeau-bonnette…très bouffante,” the editor notes that “our Ladies have adopted the fashion of redingotes” from English women. In spite of the flamboyantly trimmed hats and delicate footwear that generally accompanied the redingote, its visual similarity to men’s dress prompted the same critiques that were leveled at women throughout the century for transgressing gender boundaries by their adoption of tailored riding suits. In 1789, The Lady’s Magazine worried that,

“[O]f late, I think, women appear, in their great coats, neckcloths, and half-boots, with so masculine an air, that if their features are not very feminine indeed, they may easily be mistaken for young fellows; especially when a watch is suspended on each side of a petticoat.” (Waugh/Women 127) (Fig. 9)

While wool redingotes were most closely associated with men’s fashionable daywear, they were also made of silk. A watercolor drawing of Marie Antoinette dating to about 1780 (Fig. 11) shows the queen in an ivory redingote (likely silk) with a black collar and zigzag trimming and narrow bands of fur edging the skirt fronts and petticoat hem. An extant example in the collection of Palais Galliera (Fig. 12) with an impressive scalloped double collar is of yellow silk taffeta. In her portrait by Labille-Guiard, the Comtesse de Selve (Fig. 13) wears a chic double-breasted dark grey velvet redingote with gold cord crisscrossed around the buttons similar to the plate in the Magasin des Modes nouvelles and a matching hat with a single white plume.

Fig. 10 - Duhamel (French). Cabinet des modes, ca. 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 x 16 cm. Paris: National Library of France. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (French). Marie Antionette in a Redingote, ca. 1780. Engraving. New York: BGC Visual Media Resources Collection, 214248. Source: Fashion Muse

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (French). Redingote and Skirt, ca. 1780-1785. Tafetta, silk. Paris: Palais Galliera, 1988.121.4ab. Source: Dreamstress

Fig. 13 - Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (French, c. 1749-1803). Comtesse Charlotte Elisabeth de Selve (1736-1794), 1787. Oil on canvas. Source: Wiki

The dress that would gain particular prominence in the 1780s and the following decade was the white muslin chemise, or chemise à la reine (Fig. 14). Although Marie Antoinette was vilified in 1784 for allowing herself to be portrayed in this one-piece gown (Fig. 15) adorned only with a matching double-ruffled collar, shallow cuffs, and a sheer, gold-colored sash, the chemise was worn by many women across the socio-economic spectrum and “the evolution of this pivotal garment illuminates a period of profound change in French fashion and society” (Chrisman-Campbell 172; see also 172-199). As dress historian Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell points out, although “the chemise à la reine was similar to the female undergarment in construction… it was not identical [and] it bore a closer resemblance to the unstructured white gowns traditionally worn by young children of both sexes” (Chrisman-Campbell 172). Unlike the two-piece styles described above, the chemise was put on over the head and did not require a pannier and, while muslin was a favorite choice for this dress, “crêpe, silk gauze, lawn, and linen were also used” (Figs. 14, 15) with some of these lightweight fabrics being washable (Chrisman-Campbell 174-175). Sold by couturières and marchandes de modes, the chemise’s

“combination of practicality and novelty made [it] an essential part of the fashionable female wardrobe even before it received Marie-Antoinette’s endorsement and the soubriquet ‘à la reine.’” (Chrisman-Campbell 172, 176)

In its early iteration, the chemise was loose-fitting, with the excess fabric gathered at the neckline and shoulder seams and controlled at the waist by a wide sash, usually of a contrasting color (Figs. 14, 15). A rare surviving example of a chemise in the collection of the Manchester City Galleries “with channels sewn into the sleeves for ribbons” is similar to those worn by Marie Antoinette and Madame Lavoisier (Fig. 16), depicted with her husband by Jacques-Louis David in 1788 (Chrisman-Campbell 193). The style of arranging the sleeves into puffs seen in both paintings was called “attachées sur les bras” (Chrisman-Campbell 193). David has meticulously recorded the sheerness of Madame Lavoisier’s chemise—the dark wood floor and hem of her white petticoat are visible through the gown’s transparent cotton train.

While French women eagerly adopted the robe à l’anglaise, the redingote, and other English styles of dress and headwear, English women were quick to don the chemise (Fig. 17). An admiring husband’s description of his wife’s charms on an outing to Ranelagh (a popular London pleasure garden) that was published in the Lady’s Magazine in 1786 might well apply to Madame Lavoisier’s ensemble:

“She had nothing on but a white muslin chemise, tied carelessly with celestial blue bows; white silk slippers and slight silk stockings, to the view of every impertinent coxcomb peeping under her petticoat. Her hair hung in ringlets down to the bottom of her back…” (quoted in Cunnington/Underclothes 92)

Another husband, also “cited” in the Lady’s Magazine in the same year that Marie Antoinette’s portrait was displayed at the Salon, was confounded by his wife’s appearance in her “new frolic” that was “like none of the gowns [she] used to wear” and further perplexed by her explanation that she was garbed in a “chemise de la reine,” since he was not a “master of French.” On learning that she was, in effect, wearing “the queen’s shift,” he remonstrated “…what will the world come to, when an oilman’s wife comes down to serve in the shop, not only in her shift, but that of a queen” (quoted in Waugh/Women 123).

Fig. 14 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Chemise à la reine, ca. 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 x 16 cm. Paris: National Library of France. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 15 - Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, c. 1755-1842). Marie-Antoinette, ca. 1783. Oil on canvas; 92.7 x 73.1 cm. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1960.6.41. Timken Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 16 - Jacques Louis David (French, 1748-1825). Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794) and Marie Anne Lavoisier (Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze, 1758–1836), 1788. Oil on canvas; 259.7 x 194.6 cm. New York: The Metopolitan Museum of Art, 1977.10. Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, in honor of Everett Fahy, 1977. Source: The Met

The chemise popularized the vogue for white more broadly in this decade as is evident in portraits and fashion plates showing women in white, two-piece cotton and silk gowns and in surviving garments (Figs. 18, 19). In 1786, the Comtesse de Provence, the queen’s sister-in-law, sat for Joseph Boze who depicted her in high-styled robe à l’anglaise and petticoat of gleaming ivory silk satin trimmed with scallop-edged lace and matching bowknots and a satin-striped fichu (Fig. 20). The following year, the Magasins des Modes nouvelles illustrated a young woman in a “fourreau” (a gown with back panels stitched from the back of the neck to the hem) of white linen over a petticoat of white [silk] taffeta, and informed its readers that for morning walks, especially during fine weather, white fourreaux, robes à l’anglaise, and caracos with matching petticoats (Fig. 21) should be worn over white underpetticoats and that blue, pink, purple, and other colored underpetticoats, or “transparens,” were out of fashion.

Fig. 17 - George Romney (English, 1734-1802). Mrs John Matthews, 1786. Oil on canvas. London: Tate Museum, N04490. Presented by Miss Winifred Bertha de La Chere in accordance with the wishes of her uncle, Henry, 1st Viscount Llandaff 1929. Source: Tate

Fig. 18 - Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755–1842). Comtesse de la Châtre (Marie Charlotte Louise Perrette Aglaé Bontemps, 1762–1848), 1789. Oil on canvas; 114.3 x 87.6 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 54.182. Gift of Jessie Woolworth Donahue, 1954. Source: The Met

Fig. 19 - Designer unknown (British). Robe à l'anglaise, ca. 1780. Cotton, flax. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982.291a, b. Gifts in memory of Elizabeth Lawrence, 1982. Source: The Met

Fig. 20 - Joseph Boze (French, 1745–1826). Marie-Joséphine-Louise de Savoie (1753–1810), comtesse de Provence, 1753. Oil on canvas; 192 x w 134.5 cm. Westerham: National Trust, Hartwell House, 1548062. gift to the National Trust with the house as a hotel by Richard Broyd, 2008. Source: Art UK

Fig. 21 - Designer unknown (English). Caraco and Petticoat, ca. 1789. Fine white linen, embroidered in silk. Paris: Musée de la Mode et du Costume, 1959.97.4. Source: Dreamstress

Fig. 22 - Maker unknown (French). Gazette des atours de la Reine Marie-Antoinette pour l'année 1782, 1782. Taffeta, silk. Paris: Archives nationales, AE/I/6 n°2. Source: ARCHIM

In the 1780s, Queen Marie Antoinette, who spent extravagantly on her wardrobe and could afford the most richly brocaded silks, purchased the newly fashionable lightweight, drapey fabrics for both her informal daywear and her formal gowns. The pages of the Gazette des Atours de Marie Antoinette, an album containing fabric swatches of gowns made for the queen in 1782 (Fig. 22), are filled with taffetas (plain woven silks) in solid colors and stripes, some with ikat patterning, that were used for “Robes Turques,” “Lévites,” “Robes angloises,” “Redingotte,” “Grands habits,” “Robes sur Le petit panier,” and “Robes sur Le grand Panier” (James-Sarazin 41-44) (Figs. 2, 4, 12). The inscription next to a swatch of cream-colored taffeta ordered for a grand habit to be worn at Easter indicates that the dress was trimmed by “Mlle Bertin,” who likely lavished yards of three-dimensional trimmings onto this entirely plain fabric. In 1783, Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun reprised her 1778 portrait of Marie Antoinette (much admired by the royal consort) in which the queen wears a frothy grand habit of white silk with white-and-gold trimmings (Vigée-Lebrun updated the queen’s coiffure in the later version) (see 1770-1779 overview) A (slightly) less formal dress (probably a robe parée) dating to the 1780s (Fig. 23) in the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum said to have been worn by Marie Antoinette is of ivory satin embroidered in silk and metal threads and sequins with ribbon swags, tassels, and delicate florals and foliage in shades of pink, green, blue, and ivory.

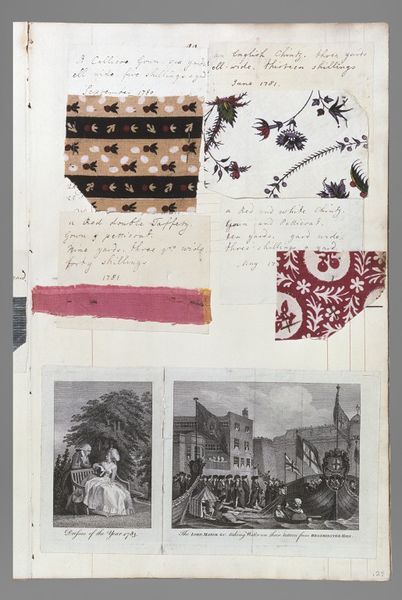

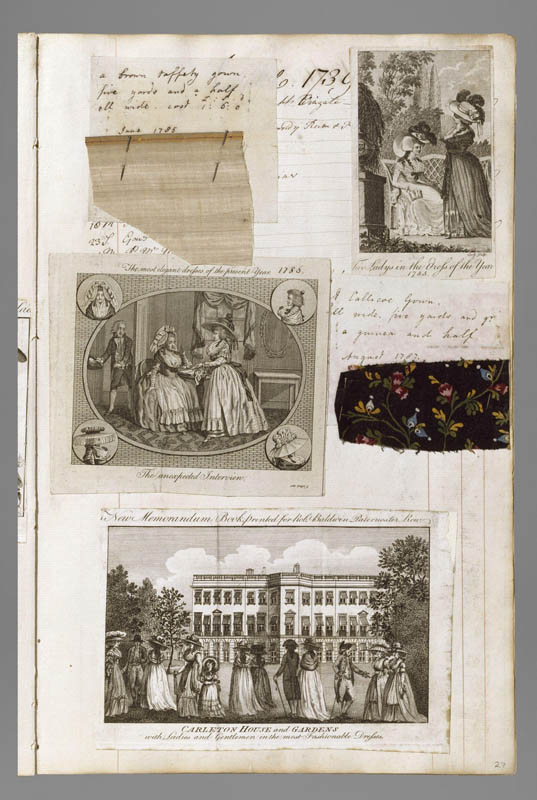

Barbara Johnson (1738-1825), daughter of a clergyman from Olney, Buckinghamshire, who kept an album with fabric swatches of all her gowns (Figs. 24 & 25) beginning in 1746 at the age of 8, bought several examples of understated silks and cottons for gowns and petticoats in the 1780s. These included a “Callicoe” with black-and-tan stripes patterned with tiny sprigs in September 1780; a “Red double Taffety” [plain weave] and “an English Chintz” with a blue, red, and green floral pattern on a white ground in 1781; “a strip’d Satin” in dark green and dusty rose-pink in December 1782; “a brown taffety” in June 1785; and two more “Callicoe[s],” one with a small meandering vine pattern in blue, yellow, and green on a black ground in August 1787 and another with small floral-and-foliate sprigs in yellow, deep pink, white, and light brown on a black ground in October 1789 (Rothstein/Barbara Johnson’s Album of Styles and Fabrics). While many British and French chintzes featured white or light-colored grounds, dark grounds such as green, brown, and black, known as “ramoneur” (chimney sweep) in French, were particularly popular in this decade and the 1790s (Fig. 25).

In addition to domestically produced printed cottons that targeted a range of consumers, elite women favored expensive, skillfully painted-and-dyed and embroidered Indian cottons for the refinement of their embellishment and the high quality of the material itself (Figs. 26, 27).

Fig. 23 - Designer unknown (French). Marie Antionette's dress, ca. 1780s. Ivory satin with silk, metal thread, sequins. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum. Source: ROM

Fig. 24 - Artist unknown. Page from Barbara Johnson's Album of Styles and Fabrics, ca. 1780s. Paper, parchment, textiles. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.219-1973. Source: V&A

Fig. 25 - Artist unknown. Page from Barbara Johnson's Album of Styles and Fabrics, ca. 1780s. Paper, parchment, textiles. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.219-1973. Source: V&A

Fig. 26 - Designer unknown (English). Dress (robe à l'anglaise), ca. 1780s. White cotton chintz with polychrome indian floral print; "compères" front with lacing; border of printed fabric at center front, hem and cuffs.. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC6978 91-11-1. Source: KCI

The main difference between the female silhouette of the 1770s and that of the 1780s was the latter’s rounder shape that was achieved with understructure, accessories, in particular, the fichu, and changes in hairstyles (Figs. 1, 5, 7, 13, 20). Although the corset (now often half-boned) was still essential in the creation of the fashionable body, the various two-piece gowns referred to above would generally have been worn with a cork-filled crescent pad, known in Britain as a “false rump” or “dried bum” and in France as a “cul de Paris” (Cunnington 336) (Figs. 28, 29). If not tied securely around the waist, the tapes might come loose, as seems to have occurred in at least one instance as reported by Town and Country Magazine in 1785:

“Lost: a Lady’s Rump in fine preservation, coming from the City Ball.” (Cunnington/336)

The admiring husband at Ranelagh noted that although his wife was unencumbered by stays under her white muslin chemise, allowing for the “advantageous” display of “her easy shape,” her long ringlets “rested upon the unnatural protuberance which every fashionable female at present chuses to affix to that part of her person,” as seen in the portrait of Marie Anne Lavoisier (Fig. 16) (quoted in Cunnington/History of Underclothes 92).

To balance this posterior rotundity, women wore large white cotton, linen, or gauze fichus loosely folded and crossed over the bust, sometimes with the ends tied around the back of the waist, creating a pouter-pigeon effect (Figs. 1, 5, 8, 18). In 1786, Sophie de la Roche commented on the “get-up of four ladies, who entered a box during the third play.”

Their “wonderfully fantastic caps and hats perched on their heads” drew “loud derision” from the audience, and “their neckerchiefs were puffed up so high that their noses were scarce visible, and their nosegays were like huge shrubs, large enough to conceal a person.” (quoted in Waugh/Women 125)

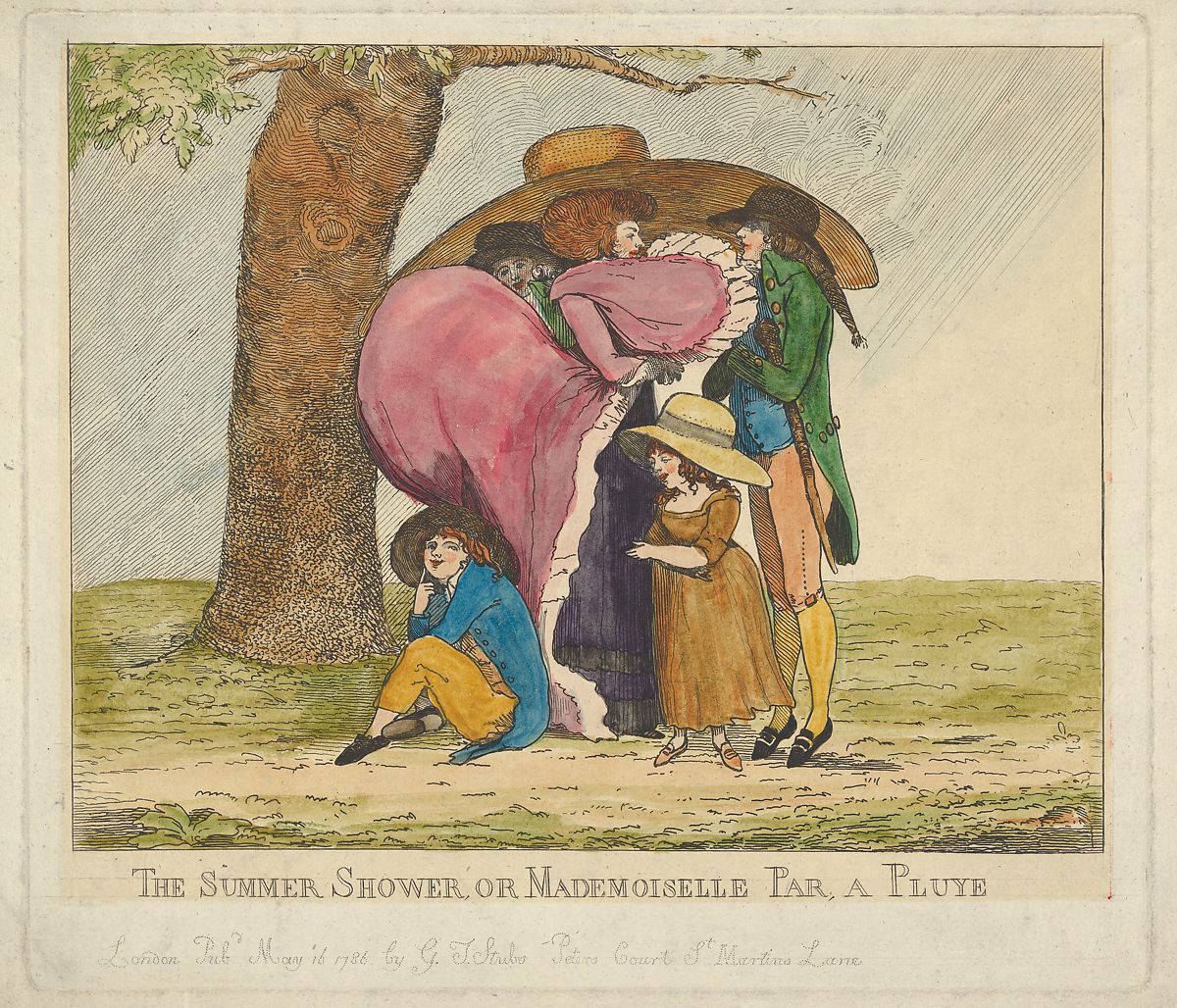

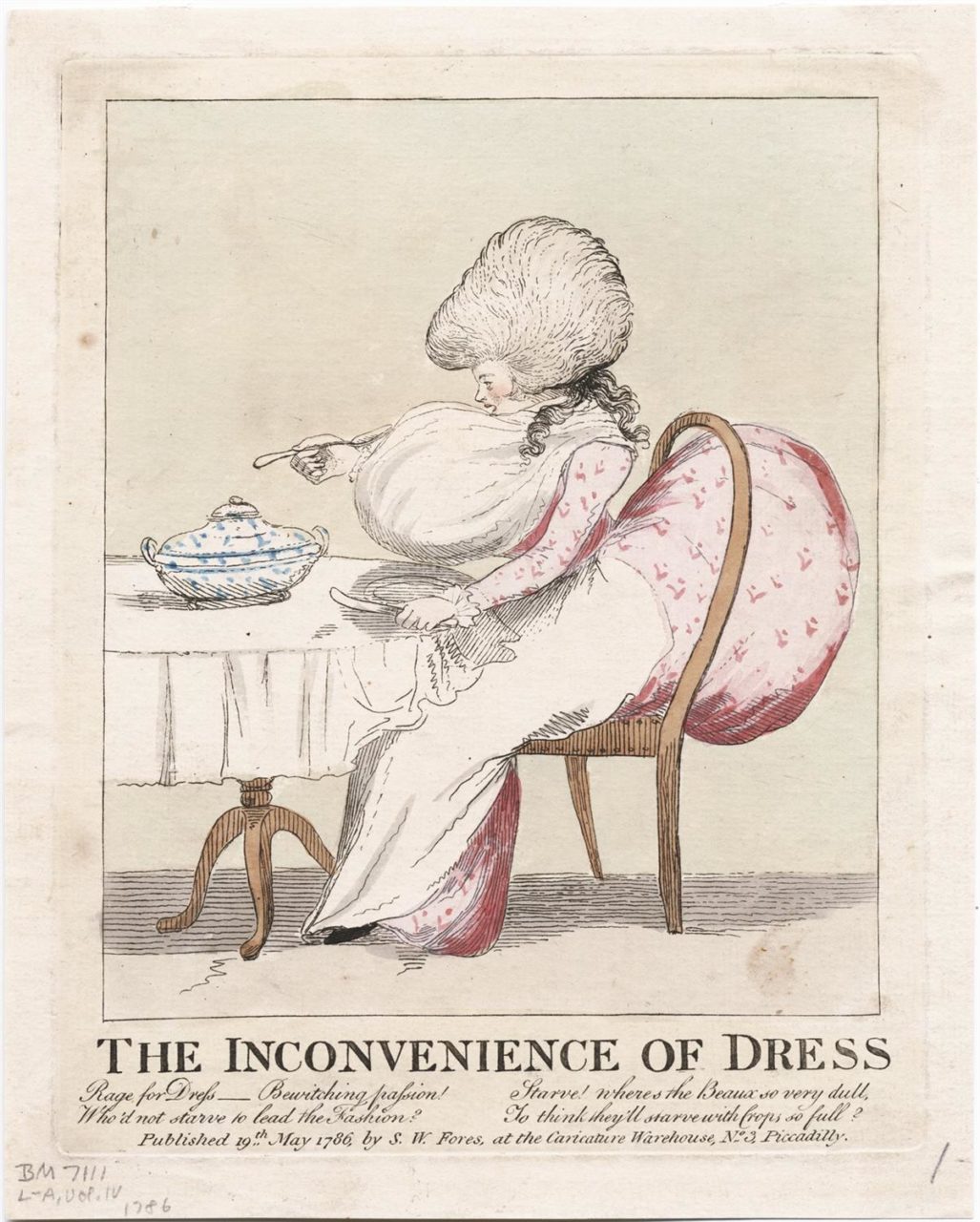

Large muffs, that were a point of fashion for both young women and men in the 1780s, further exaggerated this silhouette especially when held directly in front of the bust (Fig. 30). Caricaturists relentlessly satirized the pros—depending on one’s point of view—and mostly cons of these spherical female proportions (Figs. 31, 32).

Although sizable coiffures continued to be fashionable in the 1780s, the verticality of the previous decade’s hairstyles was replaced by an aureole-like shape that also involved the use of false hair, powder, and pomatum (Figs. 5, 8, 13, 16, 20). To accommodate these new coiffures that were more conducive to headwear, milliners confected hats and bonnets of suitably large dimensions with expansive brims and crowns topped with extravagant ribbons, plumage, and other ebullient decorations. The Galerie des Modes and Cabinet des Modes (and its subsequent versions) chart the frequent changes in these all-important accessories that communicated the wearer’s familiarity with the latest novelties that even the Cabinet’s editor sometimes acknowledged varied only slightly from what he had heralded as the most au courant style in the previous issue (Figs. 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 13, 17, 18, 20, 30, 33). In his Tableau de Paris (1783), the social commentator and urban ethnographer Sebastien Mercier commented on the fleetingness of women’s fashions—including headwear—that were out of date before he could put them to pen. The women of easy virtue who patrolled the Palais-Royal—a favorite hunting ground—

“walk two by two to catch men’s eyes dressed in the latest spoils of the milliner, mad modes too, some of them, which last a day or two, and then are forgotten even by their own inventors. The names of these fashions would fill a dictionary of several volumes folio; however, we have no such useful guide as yet….” (Mercier 207)

In France, the straw hat, associated with English country life, was sartorial shorthand for fashion’s affinity with the pastoral (Figs. 1,7, 15, 17, 18). The marchande de modes (Fig. 33), or milliner, reigned supreme in the last decades of the eighteenth century. The relative simplicity of women’s main garments in both shape and fabric during this period was almost obscured by their accompanying accessories and trimmings (Fig. 34) including “feathers, ribbons, tassels, lace, artificial flowers and other ornaments” that were provided by these fashion merchants and often considerably pricier than the gowns themselves (Chrisman-Campbell 52).

Fig. 27 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à l'anglaise, ca. 1784-1787. Cotton, metal, silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991.204a, b. Purchase, Isabel Shults Fund and Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1991. Source: The Met

Fig. 28 - Designer unknown (British). Stays, 1780-1789. Linen, linen thread, ribbon, chamois and whalebone. London: Victoria and Albert Museunm, T.172-1914. Mrs Strachan. Source: V&A

Fig. 29 - R. Rushworth (British, active 1785–86). The Bum Shop, July 11th, 1785. Hand colored etching; 31 x 44 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970.541.12. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund and Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, by Exchange, 1970. Source: The Met

Fig. 30 - Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755-1842). Madame Molé-Reymond, from the Italian Comedy (1759-1833), ca. 1786. Oil on wood. Paris: The Louvre, MI 694. Reymond, Maurice Gabrielle Hélène Françoise (model's daughter). Source: Louvre

Fig. 31 - Artist unknown (British). The Summer Shower, or Mademoiselle Par, a Pluye, May 16th, 1786. Etching, hand colored; 23.8 x 27.3 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971.564.190. The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1971. Source: The Met

Fig. 32 - George Townley Stubbs (British, c. 1756-1815). The Inconvenience of dress, 1786. Hand-coloured etching. London: The British Museum, 1851,0901.298. Donated by: William Smith, the printseller. Source: Yale University Library

Fig. 33 - Artist unknown (French). Les Belles marchandes de Paris, 1784. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France. Source: BNF

As dress historian Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell notes,

“marchandes de modes were convenient (if problematic) symbols of class, consumption, and sexuality. By displaying themselves to public view in magasins de modes (fashion shops) and in the streets, [they] provoked controversy and curiosity” and these women “came to personify fashion itself, with all its glamour and foibles.” (Chrisman-Campbell 53-54)

The most renowned marchande de modes in Paris was Rose Bertin, whose shop, “Au Grand Mogol,” was on the exclusive Rue St. Honoré. Bertin’s services to the fashion-obsessed Marie Antoinette secured her reputation among an affluent international clientele who were willing—when they settled their bills, sometimes on an annual basis—to pay her exorbitant prices and made her the target of critics, who decried her undue influence over the queen and what was perceived as her familiarity with—and even insolence towards—her high-ranking customers.

In addition to dressmakers who were instrumental in the invention and dissemination of new styles, the burgeoning fashion press on both sides of the Channel kept women in urban centers as well as rural areas increasingly up to date with changes in style. In France, the Cabinet des Modes, edited by Jean Antoine Brun, appeared in October 1785, slightly overlapping with the Galerie des Modes (1778-1787). Published every fifteen days until October 1786, “it provided its subscribers with three color engravings and eight pages of text on the latest fashions” (Jones 181). Over the next three years until December 1789, the journal, renamed Magasin des Modes nouvelles françaises et anglaises was edited by Louis Edme Billardon de Sauvigny, and, in February 1790—just six months after the fall of the Bastille—Brun took the helm once again and changed the title to Journal de la mode et du goût (Jones 181). The Cabinet des Modes (and its subsequent iterations) “provided a detailed view of how the ‘fashion system’ worked…and explicit commentary on the nature of la mode…[as well as] regularly discussing its own role in the culture of fashion” (Jones 181). In her examination of this journal, historian Jennifer Jones argues that “the fashion press played a crucial role in disseminating a new vision of the relationship between women, fashion, and commercial culture” and “relegating” fashion and its associations with frivolity and ephemerality to “the realm of taste rather than the serious realm of art and politics” (Jones 180).

Fig. 34 - Michel Garnier (French, act. 1793-1814). A Fashionably Dressed Young Woman in the Arcade of the Palais-Royal, 1787. Source: Pinterest

Significantly, although publications like the Galerie des Modes and the Cabinet des Modes depict upper-class men and women, they simultaneously reflect the growing consumption of fashion that encompassed the middle and working classes and mark a shift in the locus of trendsetting styles from the court to the city of Paris (Jones 182).

In England, Barbara Johnson’s album attests to the popularity of what were known as Pocket Books that were “issued especially for women [and] appeared in quantity…during the second half of the eighteenth century” (Rothstein 36). These small books included “pages ruled for engagements month by month” as well as a variety of information such as “hackney carriage rates; new taxes… new country dances, songs, cookery recipes…[and] one or two fashion engravings” (Rothstein 36). Beginning in 1754, Johnson affixed engravings from “16 named publications, as well as many unidentified plates” to the pages with her fabric swatches (Rothstein 36). From her home in Buckinghamshire, Johnson had access to The Ladies Complete Pocket Book (first published in 1758 and one of her favorites, judging by the 15 times that identified engravings appear in the album between 1770 and 1825); The English Ladies Pocket Companion or Useful Memorandum Book; Carnan’s Ladies Complete Pocket Book; The Ladies New Memorandum Book among several others (Rothstein 36-37) (Figs. 24, 25). In addition to Pocket Books, more fashion-focused magazines were also available such as The Lady’s Magazine (the fourth publication with that name) that began in 1770 (Rothstein 40).

Fashion Icon: LOUISE CONTAT (1760-1813), French actress

Fig. 1 - Jean-Baptiste Greuze (French, 1725–1805). Louise Contat, ca. 1786. Pastel. Source: Wiki

Fig. 2 - Jacques Philippe Joseph de Saint Quentin (French, b. 1748). 'The mad day, or the marriage of Figaro', ca. 1784. Etching; 16.4 x 10 cm. New York: The Met, 2012.136.58.2. Phyllis Massar, 2011. Source: The Met

In 1784, Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais’ controversial play and succès fou, The Marriage of Figaro, ensured the reputation of Louise Contat as a gifted actress and fashion trendsetter (Fig. 1). Although leading actresses and ballet dancers had set new styles throughout the century, the establishment of a regular fashion press beginning in the 1770s added to their visibility and renown and reinforced the mutually beneficial relationship between fashion and the theatre. Beaumarchais himself recognized this relationship in the preface to the published edition of Figaro:

“Because characters in a play show themselves to have low morals, must we banish them from the stage? What should we seek at the theatre? Foibles and absurdities? That’s well worth the trouble of writing about! They are like our fashions; we can’t correct them, so we change them.” (quoted in Chrisman-Campbell 215)

Born in Paris in 1760, Louise Contat debuted at the Comédie-Française at age 16 in 1776 in the role of Atalide in Jean Racine’s 1672 play, Bajazet. In response to the mixed reviews that acknowledged her “charming figure,” but found her talent somewhat lacking, Contat undertook further dramatic studies and lessons in elocution. Following subsequent performances in Zaïre and Britannicus, she was made a sociétaire of the Comédie Française in 1777—a decision that may also have been prompted by her liaison with a high-ranking admirer, with whom she had two children. Dubbed the “Vénus aux belles fesses” by the underground press, Contat next attracted the attention of Charles Philippe, comte d’Artois, younger brother of Louis XVI, and in December 1780, she gave birth to their son. As mistress to a member of the royal family, Contat’s career benefited and she was offered enviable roles. Her beauty and vivacity were particularly well suited to ingénue parts and her appearances in Le Vieux Garçon by Paul-Ulric Dubuisson, Les Courtisanes by Palissot, and La Coquette corrigée in the early 1780s brought her acclaim. Following her breakout role in The Marriage of Figaro, Contat enjoyed many further theatrical triumphs playing lovers, coquettes, and young mothers. In 1785, the actress was awarded a pension from the royal treasury, and she remained loyal to the Bourbon family after the outbreak of the Revolution in July 1789.

Although she was a confirmed royalist, Contat was protected by leading members of the Revolutionary government after the fall of the monarchy in August 1792; however, she was imprisoned in 1793, sentenced to death, and narrowly escaped the guillotine. In 1799, she returned to the Comédie-Française, where she reclaimed her pre-Revolutionary successes, performing until her retirement in 1809. Her salon, that she established during the Directoire (1795-99), drew guests from the highest echelons of Ancien Regime society. Contat died of cancer in 1813 and is buried in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

Although Beaumarchais’s play The Barber of Seville (1775), the first in his trilogy that introduced the scheming, upstart character of Figaro, was well received, it was the second, The Marriage of Figaro, that became a sensation (Figs. 2, 3, 4). Following its wildly successful first performance at the Comédie-Française in front of a packed house filled with members of the aristocracy, the play spawned a host of feminine fashions, named for both male and female characters including Figaro, Suzanne (maidservant to Countess Almaviva, the object of Count Almaviva’s desire, and Figaro’s wife-to-be), and Chérubin (a male page), that filled the pages of the Galerie des Modes (1778–87) and the Cabinet des Modes (1785–86). A 1785 plate (Fig. 5) from the former presents a “young and elegant Suzanne” holding a letter to “her dear Figaro” dressed in a muslin “caraco” (jacket bodice) and skirt—typical attire for a lady’s maid that “crossed over into fashion in the 1780s,” largely due to Figaro (Chrisman-Campbell 212). In the same year, a “brilliant nymph” of the Palais-Royal, with a coiffure “à la Suzanne” and a juste (another name for a hip-length jacket) “à la Figaro,” offers “to the eyes of the public the charms of her face and the elegance of her shape” that attract high praise, while another “nymph” walking in a public promenade with hopes of meeting an admirer wears a hat “à la Chérubin” (Fig. 6). The Cabinet des Modes illustrated a (presumably respectable) woman in formal dress accessorized with a gauze bonnet “à la Figaro” (Fig. 7).

In its issue of November 20, 1786, the Magasin des Modes nouvelles referred to bonnets “à la Turque” and “à la Randan” (known by some as “à la Bayard”) that owed their origin to the “exquisite taste of the famous Actress who played the role of Madame de Randan in Les Amours de Bayard, a new comedy by M. Monvel”. Lest its readers were unaware of the identity of this “famous Actress,” the editor added a note clarifying that she was “Mademoiselle CONTAT, who had already created hats à la Suzanne, à la Figaro, &c”.

Fig. 3 - J. Coutellier (French, 1776-1789). Louise Contat in the Role of Suzanne in Pierre Beaumarchais's "Le Mariage de Figaro" (The Marriage of Figaro), ca. 1784. Engraving. New York: BGC Visual Media Resources Collection, 215945. Source: Alamy

Fig. 4 - J. Coutellier (French, 1776-1789). Jeanne-Adelaide Olivier in the Role of Chérubin in Pierre Beaumarchais's "Le Mariage de Figaro", ca. 1784. Source: Alamy

Fig. 5 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Page from Gallerie des Modes, ca. 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 x 16 cm. Paris: National Library of France. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 6 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Page from Gallerie des Modes, ca. 1778-1785. Engraving; 23 x 16 cm. Paris: National Library of France. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown (French). Bonnet de gaze soufflée, à la Figaro, surmonté de deux plumes blanches soutenues par une guirland de fleurs, Dec 1st, 1785. Engraving. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen University Library, SB00002310. Source: Bunka Gakuen

In 1787, the Galerie des Modes depicted a young woman in a redingote with steel buttons and a wide-brimmed hat with striped ribbons and a large standing frill dubbed “à la Contat” after the actress herself (see Chrisman-Campbell 215). In attempting to explain the success of Contat’s hats, the Magasin des Modes nouvelles suggested at least one reason why women desired to copy actress fashions:

“Most of our ladies who have adopted these hairstyles have convinced themselves that they will make conquests as striking [as Mlle Contat’s characters had made on stage and Mlle Contat had made off stage], or at least will have the same seductive aura as Mademoiselle Contat.” (quoted in Jones 189-190)

However, the journal cautioned its readers against too closely emulating actresses and to limit their toilettes to the private rather the public sphere: “One must have the most modest, decent, naïve, soft and circumspect tone: the least bit of freedom, the slightest affectation, will give one the look of a prostitute” (quoted in Jones 190). In spite of the appreciation of their talents, their enormous popularity, and their acknowledged roles as fashion leaders, actresses were equated with the “nymphs” who sold their bodies—presumably to the highest bidder—until the turn of the twentieth century.

Menswear

Fig. 1 - Thomas Gainsborough (English, c. 1727-1788). George Drummond, ca. 1780s. Oil on canvas; 233 x w 151 cm. Oxford: The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, WA1955.62. Source: Art UK

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (English or French). Riding coat, ca. 1780s. Wool plain weave, full finish, with metallic-thread embroidery. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2007.211.46. Source: LACMA

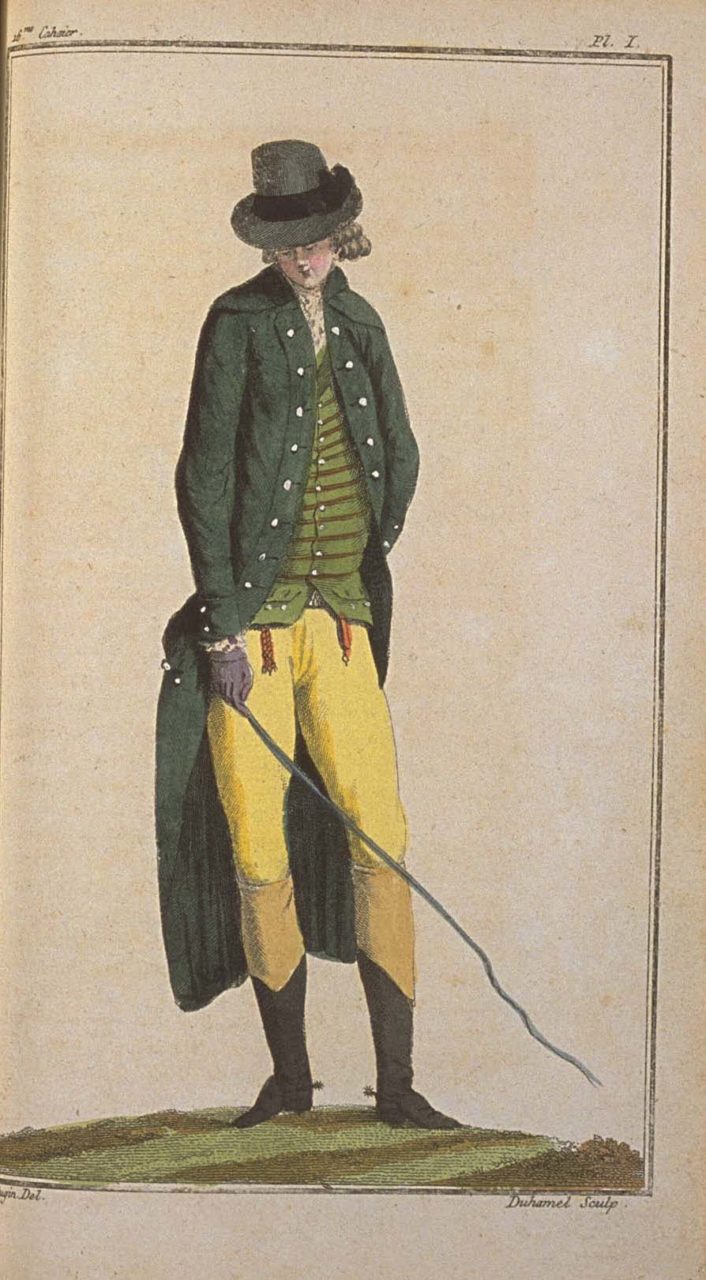

As in the 1770s, the primary influence of fashionable menswear came from England. The trend towards simplicity and informality of the English country gentleman’s attire that took hold in that decade became more pronounced in the 1780s and was emulated by fashionable young men in France and elsewhere on the Continent (Figs. 1, 2). In the French capital, frock coats, jockey hats, and riding boots were expressions of the Anglomania that swept the country at this time, as indicated by the renamed Magasins des Modes Nouvelles françaises et anglaises. Sebastien Mercier deplored this obsession with all things English:

“Just now English clothing is all the rage. Rich man’s son, sprig of nobility, counter-jumper shop clerk—you see them dressed all alike in the long coat, cut close, thick stockings, puffed stock; with gloves, hats on their heads and a riding switch in their hands. Not one of the gentlemen thus attired, however, has ever crossed the Channel or can speak one word of English… [E]nglish coats, with their triple capes, envelop our young exquisites. Small boys wear their hair cut round, uncurled and without powder…” (Mercier 148-149)

Although the writer conceded that “the dress is neat, and implies a most exact cleanliness of person,” he nonetheless implored his “young friend[s]” to “keep your national frippery” and to

“dress French again, wear your embroidered waistcoats, your laced coats; powder your hair… keep your hat under your arm, and wear your two watches, with concomitant fobs, both at once. Character is something more than dress.” (Mercier 148)

Beyond these imitations of English dress that he found distasteful, Mercier also noted other objectionable imports from France’s longstanding rival:

“Shopkeepers hang out signs—‘English Spoken Here.’ The lemonade-sellers even have succumbed to the lure of punch, and write the word on their windows… [T]he racecourse at Vincennes is copied from that at Newmarket. … [A]ll these modes and drinks and customs would have been rejected, and with disdain, by the Parisians of thirty years ago” (Mercier 149).

According to Mercier, the equine fascination among his male compatriots (that would persist into the nineteenth century) resulted in the abandonment their mistresses:

“Young men are mad about horses, and for some time have ignored the ladies of the Opera—the courtisanes resent this treatment; the young men take them out less and their horses more; until the evening, all dress like grooms; they look awkward in dress clothes.” (quoted in Waugh/Men 108)

A dashing speculator striding in the Palais Royal (Fig. 3)—seemingly having just dismounted—wears a full English ensemble comprising an umber-colored frock coat with an imbricated pattern, straight-cut striped waistcoat, thigh-hugging buckskin breeches, a “Jockey” hat, striped stockings, riding boots, and spurs. In July 1786, the Magasin des Modes Nouvelles showed a young man, ready “to mount his horse,” in a “dragon-green” double-breasted coat with mother-of-pearl buttons, a striped waistcoat, leather breeches, paired watch fobs, and “Bottes Anglaises” with silver spurs (Fig 4). Describing the sights and sounds of the Palais-Royal, Sebastien Mercier observed that

“you can hear [the young men] coming from one end of the place to the other, by the tinkle of chains for the two watches they wear.” (Mercier 206)

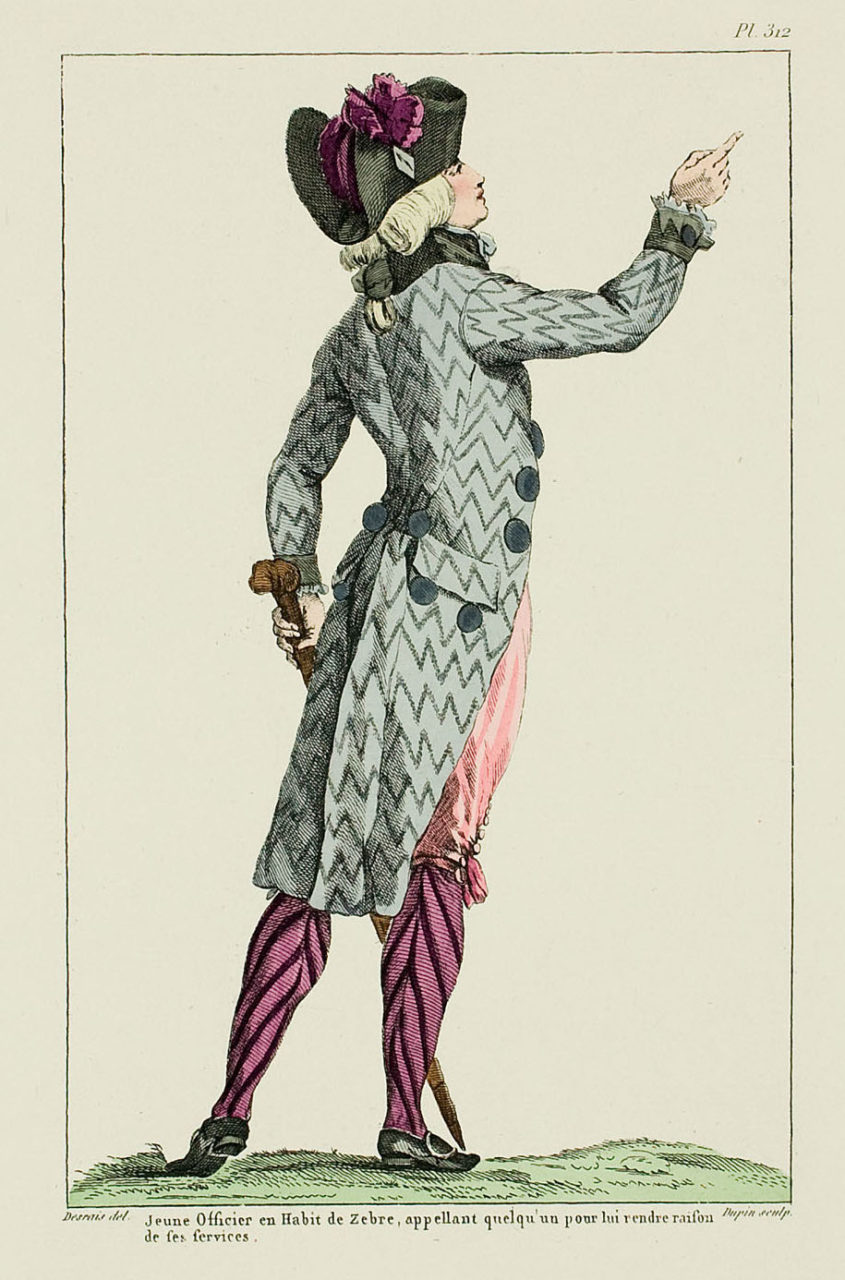

While young Frenchmen embraced the form of English attire, they often preferred more lively patterns and hues than the subdued, solid colors preferred by their counterparts across the Channel (Fig. 3). Throughout the 1780s, stripes decorated coats, waistcoats, and stockings (Fig. 5). In 1787, Mercier attributed this fashion to the zebra in the king’s menagerie:

“coats and waistcoats imitate the handsome creature’s markings as closely as they can. Men of all ages have gone into stripes from head to foot, even to their stockings.” (quoted in Ribeiro/Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe 208).

Although the waistcoat had been a focal point of the suit throughout the century, it provided additional eye-catching interest in the 1780s and 1790s, especially when worn with a plain coat and/or breeches; like women’s hats, these garments signified the wearer’s individual taste and attention to the latest trends that were often inspired by topical events including theatrical productions (such as Henry Purcell’s opera, Dido and Aeneas) and literature as well as exotic animals (Figs. 6-8).

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (French). Stock Market Speculator in Morning Clothes and Chapeau Jokei, Volume IV, plate 282, 1787. Engraving. New York: BGC Visual Media Resources Collection, 203592. Source: Dikats

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (French). English Boots and Striped Waistcoat, ca. 1780s. Engraving. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen University Library, SB00002310. Source: Bunka Gakuen

Fig. 5 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Galerie des modes et costumes français, ca. 1778-1787. Engraving. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen University Library, BB00114340. Source: Bunka Gakuen

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (French). Waistcoat, ca. 1780s. Silk, linen. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 256-1880. Source: V&A

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (French). Embroidered Waistcoat, ca. 1785-1795. Silk, embroidery. New York: Cooper Hewitt, 1962-54-47. Bequest of Richard Cranch Greenleaf in memory of his mother, Adeline Emma Greenleaf. Source: Cooper Hewitt

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (French). Waistcoat, ca. 1780-1789. Silk, linen, embroidery. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.49-1948. Source: V&A

Fig. 9 - Joseph Wright of Derby (English, c. 1734-1797). Sir Brooke Boothby, 1781. Oil on canvas. London: Tate Museum, N04132. Bequeathed by Miss Agnes Ann Best 1925. Source: Tate

Fig. 10 - Joseph Boze (French, 1745-1826). Louis-Stanislas-Xavier, comte de Provence (later King Louis XVIII, King of France) (1755-1824), 1786. Oil on canvas; 194 x 138 cm. Buckinghamshire: Hartwell House, 1548061. Source: National Trust

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (French). Suit, ca. 1780-1785. Silk, velvet, foil, sequins. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2007.211.950a-c. Source: LACMA

The contrast between men’s informal day and formal evening wear is evident in Joseph Wright of Derby’s portrait of Sir Brooke Boothby (Fig. 9) and Joseph Boze’s depiction of the Comte de Provence, younger brother of Louis XVI and future Louis XVIII (Fig. 10). Dress historian Aileen Ribeiro notes that while Boothby’s

“portrait has been seen, both in pose and in dress, as influenced by late Elizabethan and Jacobean melancholy… the costume is certainly not indicative of a melancholic déshabillé, but a definite statement of high fashion.” (Art of Dress 48)

Carefully reclining on the ground in a wooded landscape and holding a copy of Rousseau. Juge de Rousseau, Boothby wears a three-piece matching suit of soft brown wool consisting of a slim-fitting double-breasted frock with turned-down collar and wide lapels and tight sleeves that have been unbuttoned at the wrist to afford greater ease of movement, a double-breasted waistcoat, and close-fitting breeches secured with buttons above the outer knee, white silk stockings, and black low-heeled buckled shoes (Fig. 9). The neutral color and plainness of his suit sets off the whiteness of his equally plain white linen shirt and cravat, tied in a bow. Ribeiro notes that “Oxford Street in London was famous for its shops selling a wide range of cottons and linens, and was particularly admired by foreign visitors in the 1780s” (Art of Dress 48). Set at an angle on Boothby’s unpowdered hair is a hat with a circular brim and a round crown known as a “wide-awake”; by the 1780s, this style “largely replaced the cocked three-corner hat which became the preserve of the conservative and the old-fashioned” (Ribeiro/Art of Dress 49).

At the other end of the spectrum, the Comte de Provence, seated on a gilded chair upholstered in red damask, wears a richly embroidered habit à la française with coat and breeches of pale blue silk glittering with gold spangles and a coordinating white silk waistcoat, covered in embroidery (Fig. 10). A former page to Louis XVI described the king’s formal dress of the 1780s that closely corresponds to Provence’s suit:

“on Sundays and ceremonial occasions his suits were of very beautiful materials, embroidered in silks and paillettes. Often, as was the fashion then, the velvet coat was entirely covered with little spangles, which made it very dazzling.” (quoted in Waugh/Men 107)

The late-eighteen-century formal suit was distinguished from the frock not only by its rich materials, but by its standing collar that emerged in the 1760s and grew in height through the end of the century, single-breasted closure, and the inverted-V shape of the single-breasted waistcoat skirts. While the placement of the embroidery on Provence’s coat along the center front edges, cuffs and pocket flaps is consistent with that seen in earlier decades, the delicate floral sprays and bowknot motifs are typical of the last quarter of the century and reflect an overall change in aesthetic from the heavier, lush ornamentation that previously characterized this type of decoration (Fig. 11). Throughout the century, clients purchased uncut panels embroidered with all the pieces of the suit that were subsequently made up by a tailor for the individual wearer (Fig. 12).

Unlike Boothby’s plain linen, Provence’s shirt frill and cuffs are of floral needle lace (probably French) and, although his buckled shoes are low-heeled like the Englishman’s, their red color had been associated with the French court since the reign of Louis XIV. (Fig. 10). Similarly, Provence’s powdered and curled wig with its queue encased in a black silk bag was strictly relegated to court wear by the last decades of the century. And, like the page’s description of his brother the king, the count wears a jeweled epaulet and the blue ribbon with the Order of the Holy Spirit that, along with aristocratic titles, would be abolished in the early years of the Revolution (Waugh/Men 107).

At the meeting of the Estates General in May 1789, called for the first time since 1614 by Louis XVI in 1788, the sartorial display of wealth and status that distinguished the aristocratic members of the First Estate became a lightning rod for the country’s centuries-long social, political, and economic inequities. Rejecting both his class and its prerogative to wear silks and lace, the Comte de Mirabeau joined the Third Estate and donned the prescribed black wool suit and plain linen, in which he was depicted by Joseph Boze (Fig. 13)—the same artist who had painted the Comte de Provence (Fig. 10) three years earlier.

PALAIS-ROYAL

Many Galerie des Modes plates locate the fashionable figures in the Palais-Royal (Figs. 3, 14). Following its refurbishment in this decade by the hugely wealthy anglophile Philippe d’Orléans, duc de Chartres, cousin of Louis XVI, whose family had lived in the Palais-Royal since the second half of the seventeenth century, it became the epicenter of Parisian highlife frequented by elite society, bourgeois men and women, dodgy speculators, ladies of the night, and tourists from all over Europe and beyond (Fig. 34 in womenswear). The elegant, arcaded galleries were filled with shops, auction galleries, concert rooms, gambling clubs, Turkish baths, cafés, and brothels (Fig. 15). John Villiers, an English visitor in 1788, found the shops:

“the best in Paris, which produce a prodigious rent to the Duke. Every thing that is rich, brilliant, and beautiful, is exposed to sale, at these different boutiques; the splendour of which, together with the pleasantness of the walks, and the croud [sic] of well-dressed company makes this place truly enchanting and delightful.” (quoted in Chrisman-Campbell 57)

Clothing shops—and the possibility to transform oneself—were prominent in what was derisively referred to as “le Palais marchand:”

“Go to the Palais-Royal dressed as an American savage, and in the space of half an hour, you will be dressed in the most perfect fashion.” (quoted in Chrisman-Campbell 57-58)

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (French). Embroidered panels for a man's suit, 1780s. Silk embroidery on woven silk, satin stitch; stem stitch, knots and silk net; 114.9 × 56.5 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982.290a–e. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn and Alice L. Crowley Bequests, 1982. Source: The Met

Fig. 13 - Joseph Boze (French, 1745-1826). Count of Mirabeau (1749-1791), 1789. Oil on canvas; 214 x 116 cm. New York: BGC Visual Media Resources Collection, 207630. Source: AKG

Fig. 14 - Nicolas Dupin (French). Galerie des Modes, 48e Cahier, 5e Figure, pl. 222, ca. 1785. Source: Mimic of Modes

For the more skeptical Paris-dweller, Sebastien Mercier, this “Pandora’s Box,” characterized by sensory overload, was filled with seductive attractions that could lead to ruin (Mercier 205). Declaring it “unique; nothing in London, Amsterdam, Vienna, Madrid can compare with it. A man might be imprisoned within its precincts for a year or two and never miss his liberty…,” he also warned of the “vices [that] hold sway there” and the venality of the “prostitutes [and] the stock-exchange dealers [who] meet here three times a day; money is their one topic, and the prostitution of the State…” (Mercier 202, 205).

Although “prices [were] triple, quadruple the prices anywhere else,” the Palais-Royal was never without those who came and paid, “especially the foreigners [like Villiers], who love having everything the heart of man can desire assembled in one place, under one roof, for their pleasure” (Mercier 206).

On July 12, 1789, as the political situation in France (and Paris, especially) became more unstable, Camille Desmoulins, a young lawyer from Picardy, made an impassioned speech to the crowd gathered in the gardens of the Palais Royal, exhorting his fellow citizens to take up arms. Two days later, the Bastille, the hated symbol of absolute monarchy and tyranny, was stormed by an angry mob and, over the next several months, completely destroyed.

Fig. 15 - Philibert Louis Debucourt (French, 1755-1832). The Palais Royal Gallery’s Walk, 1787. Color aquatint on paper. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1924.1344. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Potter Palmer, Jr.. Source: AIC

CHILDREN’S WEAR

(BY SUMMER LEE)

Leading into the eighteenth century, new philosophies emerging from the Age of Enlightenment were changing attitudes about childhood (Nunn 98). For example, in his 1693 publication, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, John Locke challenged long-held beliefs about best practices for child-rearing. A slightly later child development theorist was Jean Jacques Rousseau. Locke and Rousseau both put forward general principles about children’s dress. However, it was not until the 1760s that their ideas were clearly reflected in children’s wear (Paoletti).

Locke and Rousseau advocated that young children receive more regular hygiene. They also believed that dressing children in many layers of heavy fabrics was bad for their health. For those reasons, linen and cotton fabrics were preferred for babies and very young children because they were lightweight and easily washable (Paoletti).

Although the tradition was in decline, some infants may have been swaddled. Swaddling was a very long-held European tradition where an infant’s limbs are immobilized in tight cloth wrappings (Callahan). The practice was losing popularity due to popular embrace of the opinions of Locke and Rousseau who opposed the practice (Paoletti).

Babies were then dressed in “slips” or “long clothes” until they began to crawl (Fig. 1) (Callahan). These were ensembles with very long, full skirts that extended beyond the feet (Nunn 99). Babies also wore tight-fitting caps on their heads.

Once a child was becoming mobile, they transitioned into “short clothes” (Callahan). Unlike long clothes, these ensembles ended at the ankles, allowing for greater freedom of movement (Callahan). Short gowns had back-opening bodices and sometimes “leading strings” attached at the back or tied under the arms (Magidson). Leading strings were streamers of fabric used to protect young children from falling or wandering off (“Childhood”)

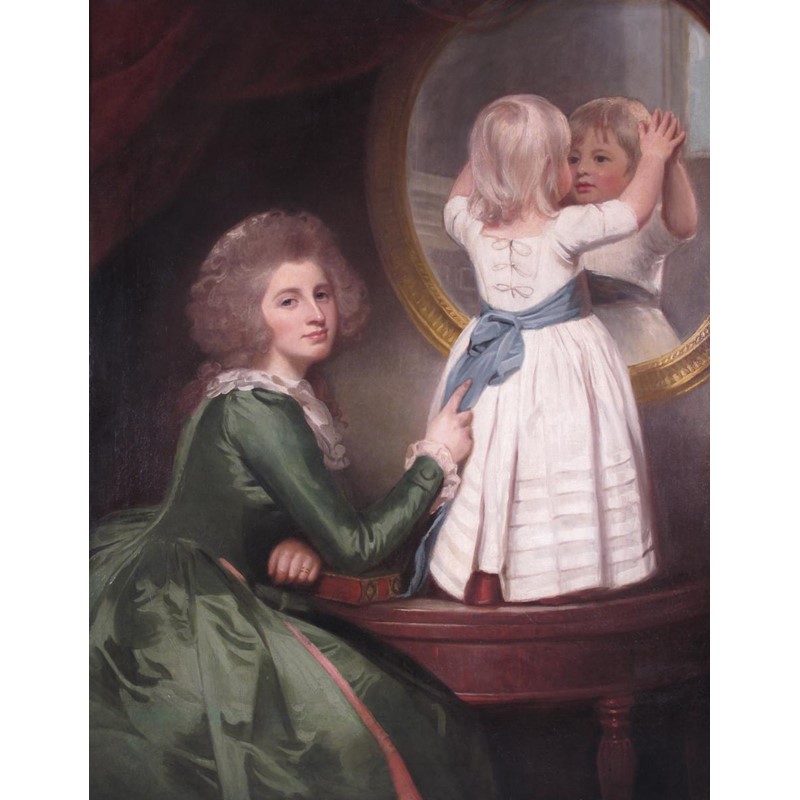

The fashion for short clothes in the 1780s had emerged in the 1760s: a white frock worn with a colored sash around the waist (Fig. 2). This style was worn by very young children of both sexes. The most common sash colors were pink and blue, although they were not used to indicate gender. A colored underslip may have also been worn, which would show through the translucent white top material (Paoletti). While this style originated with very small children, it quickly became more pervasive. By the 1780s, girls sometimes wore this style of dress even into their teenaged years (Nunn 99).

The 1780s saw a significant development in fashion for young boys. Previously, young boys wore skirted gowns until they were “breeched” by age seven, and then wore adult menswear styles (Reinier). However, new to the 1780s was a transitional type of ensemble for young boys called a “skeleton suit,” which they would wear from approximately ages three to seven (Fig. 3) (Callahan). Skeleton suits

“consisted of ankle-length trousers buttoned onto a short jacket worn over a shirt with a wide collar edged in ruffles” (Callahan).

Older boys would then wear ensembles resembling adult menswear, although the fit was typically looser and more relaxed.

Fig. 1 - Thomas Gainsborough (English, 1727-1788). Detail from The Baillie Family, ca. 1784. Oil on canvas; 250.8 × 227.3 cm. London: Tate Museum, N00789. Bequeathed by Alexander Baillie 1868. Source: Tate

Fig. 2 - George Romney (English, 1734-1802). Lady Anne Barbara Russell and her son, ca. 1786-7. Oil on canvas; 144 x 113 cm. Private collection. Source: Wooley & Wallis

Fig. 3 - Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Spanish, 1746-1828). Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga (1784–1792), 1787-88. Oil on canvas; 127 x 101.6 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.7.41. The Jules Bache Collection, 1949. Source: The Met

The Baillie Family, circa 1784, depicts James Baillie with his wife and four children (Fig. 4). Baillie’s wife holds a baby wearing a long gown, which extends well past the baby’s feet. The young boy wears a dark blue skeleton suit with a white collar, which is extremely similar to the one worn in The Oddie Children, circa 1789 (Fig. 5). However, one notable exception is the pink sash tied around his waist. The younger Baillie girl wears a white gown with a blue waist sash, and lifts her skirt to reveal a dark blue underslip. Her ensemble is not unlike those worn by the Oddie girls. The older Baillie daughter wears a more mature style of gown, yet she wears a pervasively fashionable waist sash like her younger siblings.

Fig. 4 - Thomas Gainsborough (English, 1727-1788). The Baillie Family, ca. 1784. Oil on canvas; 250.8 × 227.3 cm. London: Tate Museum, N00789. Bequeathed by Alexander Baillie 1868. Source: Tate

Fig. 5 - William Beechey (English, 1753-1839). The Oddie Children, 1789. Oil on canvas; 182.9 x 182.6 cm. Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of Art Foundation, 52.9.65. Purchased with funds from the State of North Carolina. Source: Wikimedia Commons

REFERENCES:

- Buck, Anne. Dress in Eighteenth-Century England. London: B. T. Batsford, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1148934170

- Blum, Stella, ed. Eighteenth-Century French Fashion Plates in Full Color, 64 Engravings from the “Galerie des Modes, 1778-1787.” New York: Dover, 1982. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1099092948

- Brédif, Josette. Classic Printed Textiles from France, 1760-1843: Toiles de Jouy. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/851978139

- Callahan, Colleen R. “Children’s Clothing.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed August 08, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1223089692

- “Childhood.” In European Renaissance and Reformation, 1350-1600, edited by Norman J. Wilson, 319-321. Vol. 1 of World Eras. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2001. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3034600137/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=480f4328.

- Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly. Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/909036350

- Cullen, Oriole. “Eighteenth-Century European Dress.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed September 16, 2016. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/eudr/hd_eudr.htm

- Cunnington, C. Willett. Handbook of English Costume in the Eighteenth Century. London: Faber, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/397113

- _______, and Phillis Cunnington. The History of Underclothes. New York: Dover Publications, 1992. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868279842

- “Introduction to 18th-Century Fashion.” Victoria & Albert Museum. Accessed September 16, 2016. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/i/introduction-to-18th-century-fashion/

- James-Sarazin, Ariane, and Régis Lapasin, Gazette des Atours de Marie-Antoinette: Garde-robe des atours de la reine: Gazette pour l’année 1782. Réunion des musées nationaux – Archives nationales, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/738549606

- Jones, Jennifer. Sexing La Mode: Gender, Fashion and Commercial Culture in Old Regime France. Oxford and New York: Berg, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1201426327

- Le Coton et la Mode: 1000 ans d’aventures: 10 novembre 2000-11 mars 2001, Musée Galliera, musée de la mode de la Ville de Paris. Paris: Somogy éditions d’art, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/698138631

- Magasins des Modes Nouvelles francaises et anglaises. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10461536s/f7.item

- Magidson, Phyllis. “Fashion.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 344-348. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3402800166/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=0084684d. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/961280814

- Nunn, Joan. Fashion in Costume 1200-2000. Bridgewater, NJ: Distributed by Paw Prints/Baker & Taylor, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/232125801

- Paoletti, Jo Barraclough. “Children and Adolescents in the United States.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: The United States and Canada, edited by Phyllis G. Tortora, 208–219. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed August 28, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/744701921

- Popkin, Jeremy D., ed. Panorama of Paris. Selections from Le Tableau de Paris by Louis Sebastien Mercier, based on the translation by Helen Simpson. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1101345838

- Pratt, Lucy, and Linda Woolley. Shoes. London: V & A Publications, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/880102437

- Reinier, Jacqueline S. “Breeching.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 118. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/961280814

- Ribeiro, Aileen. The Art of Dress: Fashion in England and France from 1750 to 1820. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/263551344

- _______. Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/988795293

- Rothstein, Natalie. A Lady of Fashion: Barbara Johnson’s Album of Styles and Fabrics. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/748992365

- _______. Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Boston: Little, Brown, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/438246692

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927414537

- _______. The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600-1930. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1074444804

- Weber, Caroline. Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. New York: Picador/Henry Holt and Company, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1028433074

- Wroth, William Warwick. The London Pleasure Gardens of the Eighteenth Century. London & New York: Macmillan, 1896. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/975991037

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1780-1789

Rulers:

- England: King George III (1760-1820)

- France: King Louis XVI (1774-1792)

- Spain:

- King Charles III (1759-1788)

- King Charles IV (1788-1808)

- United States:

- President George Washington (1789-1797)

Map of Europe in 1789. Source: emersonkent.com

Events:

- 1781 – Uranus is discovered

- 1783 – Treaty of Paris

- 1783 – Britain recognized Independence of American colonies

- 1785 – David’s Oath of Horatii

- 1788 – The Times is published

- 1789 – George Washington elected

- 1789-99 – French Revolution

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Fashion Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 18th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.