OVERVIEW

In the 1660s, men’s and women’s fashion took on added extravagance. Silk brocades became fashionable for womenswear again and enthusiasm for ribbons in menswear reached its peak. A new style of long collarless coat displaced the doublet by the end of the decade.

Womenswear

In the 1660s the foundation of any woman’s outfit remained her linen chemise or shift, on top of which she would either wear a boned bodice or a separate pair of stays. Stays were a sort of stiff corset that originally sought to create a smooth surface to prevent the wrinkling of expensive dress textiles, but came to be appreciated for their ability to shape the woman’s body to the desired silhouette of the period. A beautiful pink 1660s pair of stays and busk survives in the Victoria & Albert Museum collection (Fig. 1). The museum explains its construction:

“The stays are made by hand-stitching the watered silk to a layer of linen in long narrow pockets. Thin strips of whalebone are inserted into the pockets to give the stays their shape. Whalebone is in fact not bone, but cartilage from the mouth of the baleen whale. It grows in large sheets in the mouth of the whale and serves as a kind of sieve to filter out tiny krill, the whale’s primary source of food, from the seawater.”

A 1663 painting by Jan Steen (Figs. 2-3) allows a rare glimpse of stays on a 17th-century body. This unknown woman at her toilette wears stays beneath her unfastened pink silk jacket, which is edged in white fur. As this outfit makes clear, the jacket is separate from the petticoat/skirt worn below. The white edge of her chemise is just visible beneath the gold silk petticoat; she is pulling on her stockings, which would have been held up by garters above the knee. We also see her high-heeled mules discarded at her feet—another rare glimpse as 1660s skirts were typically floor-length.

Gerard ter Borch the Younger’s early 1660s painting Curiosity (Fig. 4) gives a fuller picture of different styles of dressing popular in the decade. The seated woman wears a blue velvet jacket trimmed in white fur like that seen in the Steen image, though now she’s fully dressed. Opposite her, the woman in a pink bodice has pink ribbon ties attaching her sleeves like those on the stays (Fig. 1) discussed above. As the Cunningtons explain in their Handbook of English Costume in the Seventeenth Century (1972):

“Close fitting and boned the bodice became again long-waisted, sloping to a deep point in front [1650-1675] some finished with short tabs flaring out over the hips (similar to the corset). Were mainly in vogue from 1660 to 1675.” (170)

The pink bodice comes to a very deep point and has a very low, off-the-shoulder neckline as was typical. As Daniel Delis Hill explains in The History of World Costume and Fashion (2011): “Necklines widened to encircle the shoulders and the sleeve armscye seam dropped onto the upper arm. Sleeves remained short.” (411)

Her white satin petticoat features many cartridge pleats at the natural waistline to create a very full skirt, supported by a bum roll.

Fig. 1 - Maker unknown (Dutch). Stays and busk, 1660-80. Moire silk, baleen. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.14&A-1951. Source: V&A

Fig. 2 - Jan Steen (Dutch, 1626-79). A Woman at her Toilet (detail), 1663. Oil on panel; 65.8 x 53 cm. London: The Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace, RCIN 404804. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 3 - Jan Steen (Dutch, 1626-79). A Woman at her Toilet, 1663. Oil on panel; 65.8 x 53 cm. London: The Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace, RCIN 404804. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 4 - Gerard ter Borch the Younger (Dutch, 1617-81). Curiosity, ca. 1660-62. Oil on canvas; 76.2 x 62.2 cm (30 x 24 1/2 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.7.38. The Jules Bache Collection, 1949. Source: MET

Fig. 5 - Gerard ter Borch (Dutch, 1617-81). The Letter, ca. 1660-65. Oil on canvas; 81.9 x 68.4 x 12 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 405532. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (English). A woman's bodice made from green silk, ca. 1660. Silk, linen, silver bobbin lace and spangles. London: Museum of London, 011359. Source: Museum of London

Fig. 7 - Gerard ter Borch (Dutch, 1617-81). Lady at Her Toilette, ca. 1660. Oil on canvas; 76.2 x 59.7 cm (30 x 23 1/2 in). Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 65.10. Source: DIA

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (English). Silver Tissue dress, ca. 1660. Silk and silver thread, worn by lady theophilia harris. Bath: Fashion Museum Bath. Source: Fashion Museum Bath

Cartridge pleats were sometimes also used on bodice sleeves to create the desired fullness in the elbow-length sleeves of the period. The blue silk bodice in ter Borch’s Letter (Fig. 5) features just such pleats and has yellow ribbons at the back. A green silk bodice in the Museum of London’s collection (Fig. 6) gives a sense of what these boned bodices looked like when off the body; it has a low, oval neckline and off-the-shoulder sleeves, as well as the characteristic deep point in the front and tabs at the waist. It laces up the back, which likely what the yellow ribbons in the Letter were used for (though in the painting no back-lacing is visible).

Ter Borch’s Lady at her Toilette (Fig. 7) actually shows a maid lacing up her mistress’s bodice. This sort of bodice would have been worn without stays. The applied silver bobbin lace trim was a popular decorative choice in the 1660s. The same sort of metallic lace can be seen edging the skirts in figures 4, 5 and 7. A rare surviving bodice and petticoat ensemble in the Fashion Museum Bath’s collection (Fig. 8) also features applied metallic lace vertically down the center front of the bodice and skirt and at its edges. Silver and silver-gilt decorations were extremely popular and are even seen adorning gloves in the period (Fig. 9) as well, as the Victoria & Albert Museum explains:

“As the 17th century progressed, the shape of gloves changed. The gauntlets became smaller and the length of the fingers shortened to more natural proportions. The embroidery is much denser than at the beginning of the 17th century, with a preference for metal thread over coloured silks… The precious metals have been applied in a variety of forms: strip (broad, flat length of metal), purl (a tube of densely coiled metal), thread (a thin strip of metal wrapped around a linen or silk thread) and spangles (known now as sequins).”

A 1660s bodice also in the V&A’s collection (Fig. 10) summarizes well the decade’s key trends:

“Typical of 1660s fashion are the long waist, off-the-shoulder neckline and short, full, cartridge-pleated sleeves. The bodice fastening took the form of a lacing through the eyelets at the back. It has a complex understructure of boned channels and layers of linen, with a channel for a separate busk at the front. A petticoat of matching satin, with a padded roll underneath, would have been worn with the bodice, as part of a formal ensemble. The bodice is decorated with a two-coloured silk cord in mushroom and cream, and a silk bobbin lace with silk-wrapped parchment, in green, pink, yellow, black, cream and tan.”

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (english). Pair of gloves, 1660s. Leather embroidered with silver and silver-gilt thread, silk ribbon, and spangles; 31.3 x 15.2 x 9.2 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.225&A-1968. Source: V&A

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (english). Bodice, 1660-69. Silk, linen, whalebone; 33 x 20 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 429-1889. Source: V&A

Fig. 11 - Maker unknown (English). Lady Mary Stanhope shoes, 1660s. Blue velvet with silver embroidery. Northhampton: Northampton Shoe Museum. Source: Europeana

The increasing decorative exuberance seen in the 1660s even extended to shoes as a pair of women’s blue velvet latchet-tie shoes with narrow squared toes (Fig. 11) reveals. The velvet is enhanced by elaborate floriate silver embroidery. As Rebecca Shawcross explains in Shoes: An Illustrated History (2014): “Up until this time, styles of women’s shoes had not differed significantly from those of men, yet from the 1660s a division was beginning to grow” (64). Men’s shoes were becoming plainer than women’s; see the black leather heels with pink ribbon latchet ties in figure 7, for example. Women, as we saw in Steen genre scene (Fig. 2), also wore slip-on heeled mules.

In ter Borch’s portrait of an unknown woman (Fig. 12) we see the same satin petticoat trimmed in metallic lace, but also another popular trend of the 1660s: a long line of ribbons down the front of the bodice, with additional ribbon trimmings on the sleeves. Millia Davenport explains in The Book of Costume (1948): “During the period of the beribboned male petticoat-breech, a ladder of ribbon knots, graduated in size, decorates the center line of women’s long unified bodices” (519). Daniel Preisler’s portrait of Justina Katharina Kirchmayr (Fig. 13) features an even larger and more colorful array of ribbons. Adriana Jacobusdr Hinlopen (Fig. 14) wears what appears to be thousands of tiny pale pink ribbons attached to her stomacher, encircling her sleeves and attached to bows in her hair.

Fig. 12 - Gerard ter Borch (Dutch, 1617-81). Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1665. Oil on canvas; 63.3 x 52.7 cm (25 x 20 3/4 in). Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1944.93. Source: CMA

Fig. 13 - Daniel Preisler (German, 1627-65). Justina Katharina Kirchmayr, born Imhoff (1627-1686), ca. 1660. Oil on canvas; 104 x 91.5 cm. Nuremberg: German National Museum, Gm763. Source: GNM

Fig. 14 - Lodewijk van der Helst (Dutch, 1642-93). Adriana Jacobusdr Hinlopen (1646-1736), Wife of Johannes Wijbrants, 1667. Oil canvas; 73.4 x 62.3 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, SK-A-863. Source: Rijksmuseum

Fig. 15 - Caspar Netscher (Dutch, c. 1639-84). A Woman Feeding a Parrot, with a Page, 1666. Oil on panel; 45.7 x 36.2 cm (18 x 14 1/4 in). Washington, DC.: National Gallery of Art, 2016.118.1. Source: NGA

Simpler ways of accenting the bodice remained popular as well. In Caspar Netscher’s Woman Feeding a Parrot (Fig. 15) we see the same gauzy fabric edging the neckline that had been popular in the 1650s. Netscher’s Card Party (Fig. 16) just allows us to view the lacing up the back of the standing woman’s bodice with silver ribbon laces tied decoratively at her waist; the seated woman’s dress sparkles with the metallic lace or embroidery trim we saw earlier.

Some Dutch women paired the new descending bow decoration with the low necklines being worn in France (Fig. 17); as François Boucher explains in A History of Costume in the West (1997), “women’s clothing assimilated a large number of French fashions, particularly in décolletage, after 1660” (273). England had already adopted such styles and Peter Lely’s informal drapery style of portraiture remained popular. His portrait of two ladies of the Lake family (Fig. 18) depicts one in a blue boned bodice, while the other is in a more casual bodice that fastens up the front with clasps.

Fig. 16 - Caspar Netscher (Dutch, 1639-84). The Card Party, ca. 1665. Oil on canvas; 50.2 x 45.1 cm (19 3/4 x 17 3/4 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 89.15.6. Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1889. Source: MET

Fig. 17 - Bartholomeus van der Helst (Dutch, 1613-70). Portrait of a Patrician Couple, 1661. Oil on canvas; 186 x 149 cm (73.2 × 58.7 in). Karlsruhe: Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, 235. Source: The Athenaeum

Fig. 18 - Sir Peter Lely (Dutch, 1618-80). Two Ladies of the Lake Family, ca. 1660. Oil on canvas; 127 x 181 cm. London: Tate Britain, T00058. Purchased with assistance from the National Art Collections Fund 1955. Source: Tate

Shimmering satin gowns (Figs. 16-21) remained popular as well, often in paler colors and paired with a single strand of pearls; as Davenport notes, “The exquisitely put-together satin dresses of the third quarter-century are usually in pale colors: white, through ivory, to canary yellows” (519). The relative simplicity of these dresses paired well with the increasingly elaborate hairstyles of the decade, which evolved towards tight ringlets framing the face and dangling on the chest (Figs. 19-21). Such styles later fell out of favor and in one case was even painted out of a portrait, Netscher’s portrait of Susanna Doublet Huygens (Fig. 19):

“When the portrait was cleaned in 2006, overpaint around the sitter’s head was removed to reveal an extravagant coiffure representing the epitome of French-inspired fashion in the years prior to 1670. Popularized in France by the Marquise de Sévigné, the style (known as ‘à la hurluberlu’) featured massive clusters of dangling curls to either side of the head.” (Leiden)

Fig. 19 - Caspar Netscher (Dutch, c. 1639-84). Portrait of Susanna Doublet Huygens, 1669. Oil on panel; 45.4 x 34.7 cm. The Leiden Collection, CN-102. Source: The Leiden Collection

Fig. 20 - Artist unknown (English). Ane (née Lane), Lady Fisher, ca. 1660. Oil on canvas. London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1798. Source: NPG

Fig. 21 - Jan Mytens (Dutch, 1614-70). Portrait of a Woman, 1660s. Oil on canvas; 69.9 x 57.2 cm (27 1/2 x 22 1/2 in). Los Angeles: Getty Museum, 79.PA.156. Source: Getty

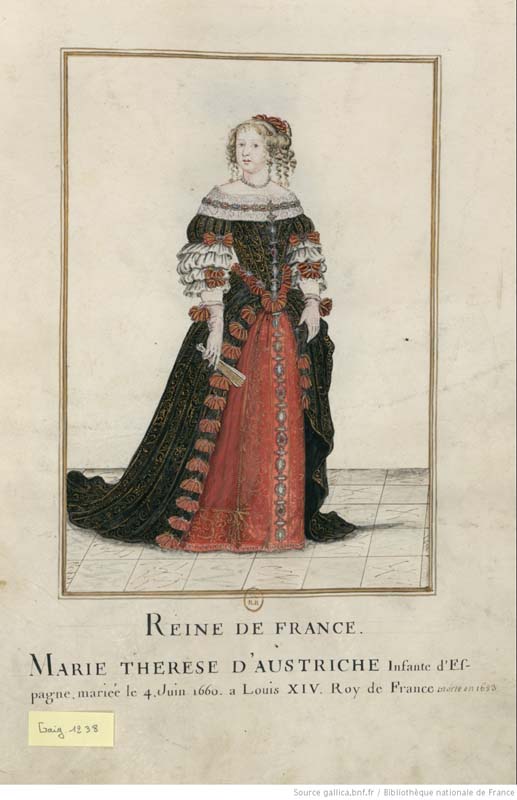

Hortense Mancini, Duchesse de Mazarin (Fig. 22), a prominent beauty at the court of Louis XIV [see “Fashion Icon” of the 1670s], also wears the hurluberlu, as does Countess Monzi (Fig. 23) and Maria Theresa of Spain, who was then Queen of France (Fig. 24). Mancini and Maria Theresa also sport immense plumed headdresses, as Davenport explains: “In France as plumes abound on courtiers’ hats, headdresses of ostrich tips are seen on great ladies” (528).

Maria Theresa had undergone an immense style transformation after her marriage to Louis XIV. At the French court she gave up the tremendously wide garde-infant she’d worn in Spain (See Fig. 3 in Menswear below) and wore the elaborate French textiles her husband became so invested in promoting. This revival of the French weaving industry shifted fashion away from plain satins to more elaborate brocade fabrics like we see in figures 22-24.

Fig. 22 - Henri Gascar (French, 1635-1701). Portrait of Hortense Mancini, ca. 1665. Oil on canvas; 120.5 x 85.5 cm (47.4 x 33.6 in). Private Collection. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 23 - Nicolaes Maes (Dutch, 1634-93). Countess Monzi, ca. 1660. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 24 - Charles and Henri Beaubrun (French, 1604-92, 1603-77). Portrait of Maria Theresa of Spain and her son in Polish costume., ca. 1664. Oil on canvas; 225 x 175 cm. Madrid: Prado Museum, P002291. Source: Prado

An early fashion drawing records Maria Theresa appearance as Queen of France (Fig. 25) including the jewel-encrusted rich textiles she favored. Charles and Henri Beaubrun’s portrait of the Queen and Dauphin (Fig. 24) gives an even clearer view of the richness of the new style of dress. Even when wearing a coronation gown with the French fleur-de-lys and lined with ermine, she wears leather gloves trimmed with hundreds of tiny red ribbon loops—a nod to the immense contemporary popularity of ribbon loop decoration.

Discussion of dress in the 1660s wouldn’t be complete without mentioning that in this period women’s riding dress was nearly identical to menswear in the period. This prompted some shock in Samuel Pepys, whose diary for June 11th, 1666 records:

“Walking in the galleries in White hall, I find the Ladies of Honour dressed in their riding garbs, with coats and doublets with deep skirts, just, for all the world, like mine; and buttoned their doublets up the breast, with periwigs under their hats; so that, only for a long petticoat dragging under their men’s coats, nobody could take them for women in any point whatever; which was an odde sight, and a sight did not please me.” (Waugh Women 61)

Fig. 25 - Artist unknown (French). Queen of France, Maria Theresa of Spain, nd. Gouache on parchment. Paris: National Library of France, FRBNF40555408. Source: Gallica

Fig. 26 - Jean Nocret (French, 1615-1672). Marie-Thérèse of Austria, Queen of France, ca. 1660. Oil on canvas; 148 x 177 cm. Versailles: Palace of Versailles, MV 2159. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 27 - Jacob Huysmans (Flemish, 1633-96). Frances Stewart, later Duchess of Richmond (1647-1702), ca. 1664. Oil on canvas; 127.7 x 104.4 cm. London: Hampton Court Palace, RCIN 405876. Source: Royal Trust Collection

A slightly more unusual example of women wearing men’s style dress is Jacob Huysmans’ portrait of Frances Stewart (Fig. 27), which Pepys also saw as the Royal Collection Trust notes: “On 26 August 1664 Samuel Pepys records seeing in the studio of Jacob Huysmans portraits including ‘Mayds of Honour (particularly Mrs Steward in a buff doublet like a soldier) as good pictures, I think, as ever I saw’.” Why Pepys approved of Stewart in a buff coat, but disliked women in masculine-style riding dress is unclear. Stewart’s tightly tailored buff coat fastens down the front with a tremendous mass of ribbons in contrast to the looser buff coats favored in the 1640s.

Fashion Icon: Barbara Villiers, later Duchess of Cleveland

From a strongly Royalist family, Barbara Villiers (Fig. 1) met Charles II in 1660 while he was living in exile in The Hague. They soon became lovers and she would go on to have six children by him—five of whom were recognized by the surname Fitzroy. She was painted many times and her image became well-known and frequently reproduced.

In the 1660s, she was:

“arguably the most influential woman in Britain at the time. She used her beauty to gain wealth and considerable political power, receiving from the king a generous pension, land grants, and aristocratic titles. Lely’s portrait of Villiers helped establish his reputation as well as her image as the preeminent court beauty.” (North Carolina Museum)

Lely claimed that “it was beyond the compass of art to give this lady her due, as to her sweetness and exquisite beauty” (Ashelford 98). Lely painted portraits of fashionable women at the royal court of which figure 1 is a part; the series became known as the “Windsor Beauties” (NC Museum). She wears a brown satin bodice that appears to be boned, with a matching petticoat as well as Lely’s signature drapery. Notable are the immense numbers of pearls worn at the neck, ears, wrist, center front of the bodice and woven into her hair—presumably gifts from Charles II.

Her every move at court was closely followed and recorded, as Jane Ashelford notes in The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society, 1500-1914 (1996):

“An experienced and discerning judge of female beauty, Pepys accepted that the King’s mistresses were the undisputed leaders of fashion. Barbara Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine, later Duchess of Cleveland – from 1670, was Pepys’s favourite, and his diary is full of details of his sightings of her, even keeping a record of those occasions on which he had seen her underwear laid out to dry in the Privy Garden at Whitehall Palace.” (98)

A miniature of Villiers by Samuel Cooper (Fig. 2) shows her wearing a daringly low-cut bodice with open seams on the sleeves allowing her chemise to peek out. Her hair is arranged in the hurluberlu hairstyle and she wears only a single strand of pearls. Her fashion influence seems to have extended perhaps even to Charles II’s new wife, Catherine of Braganza, daughter of the King of Portugal who arrived at the court in 1662 and who appears nearly identically dressed to Villiers in a Cooper miniature (Fig. 3). Against Catherine’s wishes, Charles made Villiers one of the Queen’s ladies-of-the-bedchamber (Historic UK).

She seemed to enjoy playing different roles as she commissioned portraits in various guises, including as the goddess Minerva, as a shepherdess, as Mary Magdalene (Fig. 4) and in perhaps the most daring role, as the Madonna, with her son Charles Fitzroy as the Christ child (Fig. 5). In 1670 she was made Duchess of Cleveland.

Fig. 1 - Sir Peter Lely (Dutch, 1616-80). Barbara Villiers, later Duchess of Cleveland (1640-1709), ca. 1662-65. Oil on canvas; 127 x 101.6 cm (50 x 40 in). Raleigh: The North Carolina Museum of Art. Gift of the Van Diemen-Lilienfeld Galleries and the Dalzell Hatfield Galleries in memory of William R. Valentiner. Source: NCMA

Fig. 2 - Samuel Cooper (English, 1609-72). Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland (1641-1709), 1661. Watercolour on vellum laid on card with a gessoed back; 8 x 6.5 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 420088. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 3 - Samuel Cooper (English, 1609-72). Catherine of Braganza (1638-1705), ca. 1662. Watercolour on vellum laid on card with a gessoed bac; 12.3 x 9.8 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 420644. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 4 - Sir Peter Lely (Dutch, 1618-80). Barbara Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland, ca. 1662. Oil on canvas; 188 x 128.3 cm (74 x 50.5 in). Kent: Knole, NT 129855. Source: National Trust Collections

Fig. 5 - Sir Peter Lely (Dutch, 1616-80). Barbara Palmer (née Villiers), Duchess of Cleveland with her son, probably Charles FitzRoy, as the Virgin and Child, ca. 1664. Oil on canvas; 124.7 x 102 cm (49 1/8 x 40 1/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 6725. Purchased with help from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, through the Art Fund (with a contribution from the Wolfson Foundation), Camelot Group plc, David and Catharine Alexander, David Wilson, E.A. Whitehead, Glyn Hopkin and numerous other supporters of a public appeal including members of the Chelsea Arts Club, 2005. Source: NPG

Menswear

The 1660s was a period of transition in menswear from the shrunken doublet and petticoat breeches to the adoption of the long straight-cut coat and vest. This will ultimately result in the adoption of the coat, waistcoat and knee breeches that will dominate men’s fashion for more than a century, but that combination was not firmly established until 1680 (Waugh Men 16).

At the start of the decade one finds men wearing the short bolero-style doublet with a bloused shirt appearing at the open seams, with large ruffled cuffs and often worn buttoned only from the collar to the breastbone; an example can be seen in Quirijn van Brekenkam’s Sentimental Conversation (Fig. 1).

Ribbon loop decorations remained extremely popular at the waist, doublet cuffs and at the sides of the petticoat breeches. Petticoat breeches, so named for their resemblance to women’s skirts, were extremely full-cut open breeches that hung freely down to the knees. They were so capacious it was possible to put both legs into one of the breeches as Samuel Pepys’ Diary records: “1661. April 6. Among other things met with Mr. Townsend, who told his mistake the other day, to put both his legs through one of his knees of his breeches, and went so all day” (Waugh Men 47).

Fig. 1 - Quirijn van Brekelenkam (Dutch, 1622–ca. 1669). Sentimental Conversation, early 1660s. Oil on wood; 41.3 x 35.2 cm (16 1/4 x 13 7/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 32.100.19. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931. Source: The Met

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (English). Doublet and petticoat breeches of figured silk, associated with Edmund Verney, ca. 1660. London: Victoria and Albert Museum. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 3 - Jacques Laumosnier (French, c. 1669-1744). The interview of Louis XIV and Felipe IV in the island of the Pheasants, ca. 1659-99. Oil on canvas; 89.1 x 130 cm (35 x 51.1 in). Le Mans: Musee de Tesse, LM 10.101. Source: Wikipedia

A surviving set (Fig. 2) from the Verney collection shows the characteristic silhouette and the enthusiasm for ribbon; the Verney set features six different types of ribbon that total 216 yards in length (Reynolds 92). Waugh affirms the fashionability of this trend in The Cut of Men’s Clothes, 1600-1900 (1964):

“it was in the 1650s and 60s on the very full petticoat-breeches that ribbons really ran riot—loops on the shoulders, round the doublet sleeves, the shirt sleeves, the cravat, round the waist, sides and bottoms of the breeches. Several hundred yards of ribbon might be used to decorate one suit.” (17)

While the Verney suit is English, the trend had originated in France as a painting of the meeting of King Louis XIV of France and King Philip IV of Spain makes clear (Fig. 3). Louis XIV wears a gold doublet and petticoat breeches adorned with red ribbon decorations (as the “Sun King” Louis XIV favored golden and red colors). His doublet even features the thin panes on the sleeves that the Verney doublet has as well, which allow the white of the shirt to show through.

Spanish menswear is plainer, favoring the stiffened semicircular collar (golilla), instead of the large floppy lace collar preferred by the French. Note also Louis XIV’s enormous shoe bows in contrast to the plainness of Philip IV’s black shoes. French courtiers’ hair is elaborately styled into curls compared to the limp locks of the Spaniards. After this meeting, Spanish fashion will also evolve toward the French styles (Davenport 523).

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (English). Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll; Lady Anne (née Mackenzie), Countess of Argyll, 1660s. Oil on canvas; 110.1 x 163.2 cm (43 3/8 x 64 1/4 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 3902. Source: NPG

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (English). Doublet and Trunk Hose worn by the 6th Duke of Lennox, ca. 1665. Silk and silver tissue. Edinburgh: National Museum of Scotland, A.1947.257. Source: NMS

Not all in England welcomed the adoption of French trends. John Evelyn published a pamphlet, Gentle Satyr: Tryannus or the Mode in a Discourse of Sumptuary Lawes in 1661 which questioned why the English, “‘a nation so well conceited of themselves’, should ‘generally submit themselves to the French of whom they speake with so little kindness” (Ashelford 91).

Nonetheless the French fashions dominated English dress as a portrait of Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll further attests (Fig. 4). Charles II himself is shown wearing a short doublet with beribboned breeches in a dancing scene (Fig. 5). A surviving doublet made of silk and silver tissue worn by the 6th Duke of Lennox (Fig. 6) shows the intensity of ribbon loop decoration and the luxury of the textiles then worn.

Fig. 5 - Hieronymus Janssens (Flemish, 1624-93). Charles II dancing at a Ball at Court, ca. 1660. Oil on canvas; 140.2 x 213.8 cm. Berkshire: Windsor Castle, RCIN 400525. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 7 - Gerard ter Borch (Dutch, 1617-81). Portrait of a Young Man, ca. 1663. Oil on canvas; 67.3 x 54.3 cm. London: The National Gallery, NG1399. Source: NG

The interview of Louis XIV and Philip IV (Fig. 3) also shows the adoption of cannons, wide ruffles at the knees that typically were fastened to the tops of the stockings (Davenport 518). Louis XIV wears a white set, while the courtier behind him has a tier of pink cannons; the Cunningtons explain: “Canons were usually attached as decorative additions to the stockings, and when worn almost always accompanied petticoat or open breeches, and were never worn with closed breeches” (161).

It was at this time that hose definitely switched from being a term for breeches to being associated with stockings (Cunningtons 158). Boots were worn less frequently, typically only for riding, but the stocking plus cannons effect resembled the earlier favored boot hose of the 1640s.

French styles met resistance in other countries as well, but remained popular. A portrait of an unknown Dutch young man by Gerard ter Borch ca. 1663 shows him in an all-black version of the shrunken doublet, full petticoat breeches, with ample cannons at the knees and a wide expanse of white shirt and shirt cuff ruffles visible. The National Gallery comments:

“Such ostentatious dressing was not universally approved of in the Netherlands at the time. Stricter Calvinists (who followed Calvinism, a branch of Protestantism) would certainly have raised their eyebrows at what one contemporary writer referred to as ‘immoderately loose and long garments… redolent of over-abundance and profligacy’.”

The young man also models a popular Dutch hat style of the 1660s, the tall sugarloaf or steeple crown hat that featured a truncated conical shape (Hill 405).

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (Italy). Doublet, 1660s. Watered silk lined with silk, trimmed with parchment lace. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.324-1980. Source: V&A

Fig. 9 - Samuel Cooper (English, 1609-72). James, Duke of York, later James II, 1660-61. Portrait miniature, watercolour on vellum; 8 x 6.4 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, P.45-1955. Purchased with Art Fund support. Source: V&A

Fig. 10 - Wallerant Vaillant (Dutch, 1623-77). Louis XIV, 1660. Pastel; 57.7 x 43.4 cm. Versailles: Palace of Versailles, V.2014.56.1. Source: Versailles

A surviving silk doublet in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection (Fig. 8) shows very similar truncated proportions and ample volume of visible shirt. The very full matching petticoat breeches are too fragile to display but have been faithfully reproduced, giving a good idea of the total look.

As for grooming and hair styles of the day, James, Duke of York (Fig. 9) provides a good example:

“men’s hair is now longer and fuller than was fashionable earlier in the seventeenth century. It is coaxed here into soft waves and ringlets, arranged carefully to fall in symmetrical locks over the chest and back.” (Cumming 93)

Men also favored thin mustaches, which were worn by both Charles II and Louis XIV (Fig. 10). See another example on painter William Bruce (Fig. 13). Natural-looking wigs were also beginning to be worn; initially styled like normal hair, wigs will become increasingly artificial as the century progresses. As Diana de Marly explains in Fashion for Men: An Illustrated History (1985):

“The early periwigs were very curly around 1660, but those of the 1670s had ringlets. Their introduction was gradual. The naval administrator Samuel Pepys took the plunge in 1663, James Duke of York did so in February 1664 and Charles II not until April when he was going grey. Louis XIV, for once, took even longer, sporting his own abundant locks, of which he was very proud, into the next decade. Wigs proved an excellent illustration of rank, for they cost several pounds, so the peasantry could not copy them.” (55)

While Louis XIV may have lagged in adopting a wig, he did popularize a new silhouette at court, by adopting the justaucorps, which was a type of loose overcoat that had already been worn in military costume; it “had short sleeves and was long and slightly flared at the bottom” (Boucher 258). As Boucher explains: “In 1662, according to Bussy-Rabutin, Louis XIV granted first a dozen, then about forty of his familiars permission to wear clothes similar to his own – a blue justaucorps lined with red ornaments, and a red veste or jacket – when staying at Saint-Germain or Versailles… first example of a codified form of Court costume.” (258)

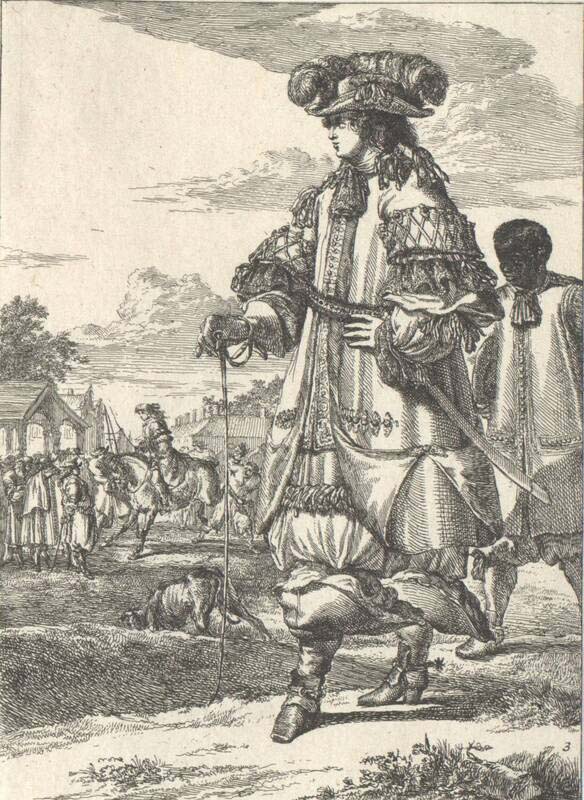

The courtier at far left in the scene of Louis XIV and Philip IV meeting (Fig. 3) seems to be wearing a long blue justaucorps-style garment. The justaucorps supplanted the doublet, which slowly evolved toward a collarless, sleeveless vest. The justaucorps was very plain in cut as it hung loosely in this decade and was not yet tailored to the body. Duke Maximilian Philipp of Bavaria (Fig. 11) wears a short-sleeved, long, loose-cut justaucorps-style outer garment, which he pairs with a truly impressive amount of ribbon trim and pleated lace cannons. An early Dutch fashion print also features two men in long, loose justaucorps.

Charles II introduced a version of the justaucorps to the English court, where he called it a vest. Like the justaucorps it was a long, collarless coat which hung so low that the petticoat breeches were no longer visible; their invisibility eventually resulted in a simplification of their style (Ashelford 92). Cravats, long strips of linen tied at the neck often with lace at the ends, became fashionable as these collarless coats were adopted. The name for the cravat “is said to be derived from Croat as such neckcloths were first seen on Louis XIV’s regiment of Croat mercenaries” (Waugh Men plate 7). The men in figures 12 and 13 all wear cravats. As the men in figures 4, 7, 9, and 11 especially demonstrate, the long hairstyles favored in the period mostly obscured the fine lace collars that men wore previously over their shoulders. The cravat concentrated the collar/lace at the center front where it wasn’t obscured by the hair or increasingly the periwig. Boucher explains more about the cravat’s adoption:

“it was already worn by soldiers, simply knotted and hanging loosely. Civilian costume gave it greater variety and imagination, with panels of rich lace and a fairly full butterfly bow of ribbon under the chin. Cravats were made ready-tied, mounted on a ribbon which was fastened at the back of the neck.” (265)

The portrait of William Bruce (Fig. 13) shows one other fashionable style of informal dress in this period, namely the dressing gown. While Bruce’s gown may be silk, in the 1660s Indian cottons also become fashionable for dressing gowns:

“In the 1660s the East India Company had introduced the English to chintz, a painted or printed cotton cloth made in India which was used as a furnishing fabric and for the loose informal gowns worn at home. Its brilliant colours, the fastness of the dyes used and the adaptation of native designs to suit English taste ensure the popularity of the materials.” (Ashelford 110)

A rival calico (white or unbleached cotton) printing industry soon developed in England and “by 1700 calico printing was flourishing” (110).

Fig. 11 - Sebastiano Bombelli (Italian, 1635-1719). Duke Maximilian Philipp of Bavaria (1638-1705), 1666. Oil on canvas; 212 x 130 cm. Dresden: Old Masters Gallery, Inv.No. Mon 638. Source: SKD

Fig. 12 - Romeyn de Hooghe (Dutch, 1645-1708). A nobleman with an African, sheet 3 from the series "Figures a la mode", 17th century. Etched paper; 16.2 x 11.8 cm. Vienna: Museum of Applied Arts, KI 1967-3. Source: MAK

Fig. 13 - John Michael Wright (English, 1617-94). Sir William Bruce, c 1630 - 1710. Architect, ca. 1664. Oil on canvas; 72.4 x 61 cm. Edinburgh: National Galleries Scotland, PG 894. Source: NGS

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (Swedish). Count Herman Wrangel of Salmis, ca. 1660s. Stockholm: Skokloster Castle, SKO 707. Source: LSH

Fig. 2 - Hendrick Berckman (Dutch, 1629-79). A Young Boy with a Dog, ca. 1667. Oil on panel. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Kolt (Frock). Worn by Karl XI of Sweden, 1660. Silk with silver and gold embroidery. Stockholm: Livrustkammaren, 31311 (3450). Source: LSH

Portraits of children can be more reliable records of fashionable dress as they were less frequently put into imagined or classical informal dress. See, for example, Peter Lely’s portrait of James II with Anne Hyde, Princess Mary and Princess Anne (Fig. 5). While Anne Hyde is in the loosely draped stylized garb Lely specialized in, Princess Mary is dressed in a densely brocaded silk, with the defined waistline fashionable in everyday dress. Note, however, her dress has leading strings attached, which were not a feature of adult dress. Sometimes even children were dressed in Lely’s characteristic fashion for portraiture, however, as in the portrait of Lady Elizabeth Seymour (Fig. 6). David Scougall’s portrait of the young Lord David Hay (Fig. 7) shows the lad in a long justaucorps-style coat, heavily adorned with braid and red ribbon loops.

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (Flemish). Portrait of Three Boys, ca. 1660. Oil on canvas. Ghent: Museum of Fine Arts. Source: Clothes Tell Stories

Fig. 5 - Sir Peter Lely (Dutch, 1618-8-). James II, when Duke of York with Anne Hyde, Princess Mary, later Mary II, and Princess Anne, ca. 1668-85. Oil on canvas; 168.6 x 194 cm. Berkshire: Windsor Castle, RCIN 405879. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 6 - Sir Peter Lely (Dutch, 1618-80). Portrait of Lady Elizabeth Seymour (d.1697) when a child, ca. 1660. Oil on canvas; 125.5 x 103 cm (49 1/2 x 40 1/2 in). Private Collection. Source: Sothebys

Fig. 7 - David Scougall (Scottish, 1654-82). Portrait of Lord David Hay (1656-1726), 1660s. Oil on canvas; 91.5 x 76.1 cm. Private Collection. Source: Sothebys

References:

- Ashelford, Jane, and Andreas Einsiedel. The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society, 1500-1914. London: National Trust, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/759883168.

- Boucher, François, Yvonne Deslandres, and John Ross. A History of Costume in the West. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/443676264.

- Cumming, Valerie. A Visual History of Costume: The Seventeenth Century. 3. London: Batsford, 1984. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/9761398.

- Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Emily Cunnington. Handbook of English Costume in the Seventeenth Century. Boston: Plays, Inc, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/755269282.

- Davenport, Millia. The Book of Costume. New York: Crown Publishers, 1948. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/922657048.

- De Marly, Diana. Fashion for Men: An Illustrated History. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1985. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/752978274.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950.

- Historic UK. “Barbara Villiers.” Accessed July 2, 2020. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Barbara-Villiers/.

- Leiden Collection. “Portrait of Susanna Doublet Huygens.” Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.theleidencollection.com/artwork/portrait-of-susanna-doublet-huygens/.

- North Carolina Museum of Art. “Barbara Villiers, Later Duchess of Cleveland (1640-1709) – NCMALearn.” Accessed June 30, 2020. https://learn.ncartmuseum.org/artwork/barbara-villiers-later-duchess-of-cleveland-1640-1709/.

- Royal Collection Trust. “Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland (1641-1709).” Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/4/collection/420088/barbara-villiers-duchess-of-cleveland-1641-1709.

- Royal Collection Trust. “Jacob Huysmans (c. 1633-96) – Frances Stewart, Later Duchess of Richmond (1647-1702).” Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.rct.uk/collection/405876/frances-stewart-later-duchess-of-richmond-1647-1702.

- Royal Collection Trust. “Jan Steen (Leiden 1626-Leiden 1679) – A Woman at Her Toilet.” Accessed June 30, 2020. https://www.rct.uk/collection/404804/a-woman-at-her-toilet.

- Royal Collection Trust. “Sir Peter Lely (1618-80) – Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland (ca 1641-1709).” Accessed July 3, 2020. https://www.rct.uk/collection/404957/barbara-villiers-duchess-of-cleveland-ca-1641-1709.

- Shawcross, Rebecca. Shoes: An Illustrated History. London: Bloomsbury, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/890162083.

- V and A Collections. “Pair of Gloves | V&A Search the Collections,” June 15, 2020. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O78794.

- V and A Collections. “Bodice | V&A Search the Collections,” June 30, 2020. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O137794.

- V and A Collections. “Stays and Busk | V&A Search the Collections,” June 30, 2020. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O10446.

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes, 1600-1900. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927414537.

- Waugh, Norah, and Margaret Woodward. The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600-1930. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/894728161.

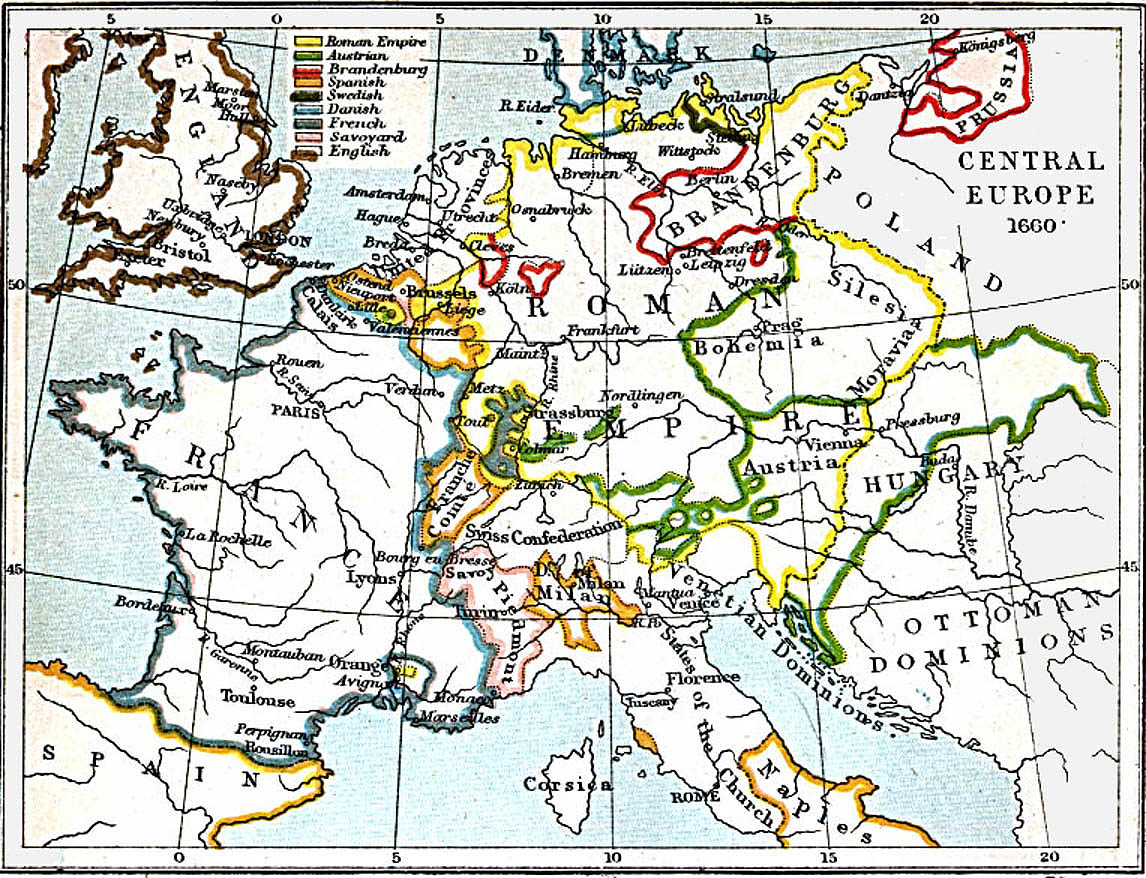

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1660-1669

Rulers:

- England: Charles II (1660-1685)

- France: Louis XIV (1643-1715)

- Spain:

- Philip IV (1621-1665)

- Charles II (1665-1700)

Central Europe 1660 A.D. Source: The University of Texas at Austin

Events:

- 1666 – Charles II introduces the vest (a style of long coat) to England.

- 1666 – Great Fire of London.

- 1667 – John Milton’s Paradise Lost

- 1668-1685 – Palace of Versailles built

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 17th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.