OVERVIEW

The court of Burgundy, where courtiers vied for status in countless variations of houppelandes, huques and chaperons continued to dominate fashion in Europe during this decade. Meanwhile in Italy, where we find some of the earliest surviving fashion designs, distinctive styles inspired by classical antiquity signaled a new direction.

Womenswear

During this decade, the most notable change in women’s fashion was not a new style of garment or headdress, but rather a change in the idealized fashionable body as depicted by artists. Large oval heads, narrow shoulders and elongated torsos with swollen abdomens, features that were already seen in the 1420s, become much more pronounced in the 1430s, and they were reinforced by posture and gesture (Fig. 1). Women are often shown leaning back and pushing their hips forward, sometimes holding the extra length of their garments in front of their rounded bellies so that they appear to be in the advanced stages of pregnancy (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). The Devonshire Hunting Tapestry: Boar and Bear Hunt, 1425-1430. Tapestry woven with wool warp and weft; 1023 x 385.4cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.204-1957. Source: VAM

The foundation of women’s dress remained the linen chemise, the basic undergarment worn by all classes (Boucher 445). Over it went a full-length dress with a different name in each country and region, such as kirtle in England, côte-hardie in Burgundy and France, and cotta or gamurra in Italy (Herald 52). Most women’s dresses were made of wool, since silk textiles were only accessible to the aristocracy and the rich middle class (Piponnier and Mane 88). To prolong the life of the garment and achieve a smooth, close fit, dresses were lined in linen.

In the foreground of Falconry (Fig. 3), one of the four Devonshire Hunting Tapestries depicting Burgundian courtiers engaged in their favorite sport and mingling with country people, we see a young woman standing by a millwheel with her dress tucked up, showing the linen lining of her upturned skirts as well as her chemise underneath. The tapestry weavers have represented the chemise using a repeating geometric pattern in low contrast, suggesting that it was made of a linen damask; the ruffle at the hemline is an interesting feature, intended to support the full skirts of the dress. The light green dress is very tightly fitted through the upper body and sleeves, which fasten down the lower arm with buttons and are turned up at the wrist to form a cuff. The young woman also wears a linen partlet with an open collar that fills in the neckline of her dress; it is kept in place by ties under the arms.

Similar styles can be seen in The Hours of Margaret of Orléans, an illuminated manuscript made in Paris or Angers circa 1430, where two miniature figures in a decorative floral border wear dresses that contrast in color and fit (Fig. 4). The young woman in red, whose long, exposed hair suggests she is unmarried, wears a front-lacing dress and a linen partlet with a collar. The turned-up sleeves at the wrist reveal the linen lining of the dress, or the long sleeves of the chemise, forming cuffs.

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown (French). Detail of Two Women in Floral Border, Hours of Margaret of Orléans, ca. 1430. Manuscript. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale, Latin 1156B, folio 172r. Source: Gallica

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Detail from the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries: Falconry, 1430s. Tapestry; 445 x 1075.9 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.202-1957. Source: VAM

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (French). Detail of Two Women with Vases of Flowers, Hours of Margaret of Orléans, ca. 1430. Manuscript. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale, Latin 1156B, folio 150R. Source: Gallica

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Detail from the Boar and Bear Hunt Tapestry, 1425-1430. Tapestry woven with wool warp and weft; 1023 x 385.4cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.204-1957. Source: VAM

The sleeves were often the only part of the dress visible under the outer garments that remained the focus of fashion. Boar and Bear Hunt (Fig. 1), the earliest of the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, depicts the fashions of the early 1430s. The two women near the center of the tapestry wear distinctive versions of the houppelande (Fig. 5). This full-length outer garment of wool or silk was the third layer of a woman’s costume (Van Buren and Wieck 307). Houppelandes could look very different depending on their materials and decoration and the style of their sleeves. The woman in blue wears a houppelande in an established style, with a high waistline marked by a wide belt, and the long funnel-shaped sleeves called bombard sleeves (Van Buren and Wieck 295). It was probably made of fine Flemish wool with a lining of white fur, visible at the sleeves and hemline. We can also glimpse the sleeves of the red dress she wears under the houppelande, matching the red belt worn over it. What makes this woman’s houppelande special is the gold-embroidered decoration of reversed letters, spelling out “monte le désir,” or moult le désir,” scattered across the left sleeve. The letters are reversed because the weavers may not have compensated for the fact that they worked from the back of the tapestry when representing the cartoon, or tapestry design (Cavallo 24, Victoria and Albert Museum). Embroidered personal emblems or mottos continued to be highly fashionable (Frick 197).

The woman next to her commands attention with a magnificent red houppelande made of brocaded Italian voided velvet. Instead of sleeves, it has a panel of the velvet, lined in ermine, hanging from the shoulders like a cape. Given ermine’s association with royalty (Evans 43), this houppelande is rather like a coronation cape. It reveals the full sleeves of her blue dress, which are gathered into a band at the wrist. The prominent placement of these figures and their particularly sumptuous attire invites speculation that they might represent Isabella of Portugal, who became the third wife of Duke Philip the Good in January of 1430, and her lady-in-waiting Jeanne d’Harcourt. Isabella was considered dowdy by the Burgundians when she first arrived, and much of her trousseau had been lost at sea. She then received many splendid gifts, and Jeanne d’Harcourt was charged with accompanying her everywhere and teaching her the etiquette of the Burgundian court. After lavish wedding celebrations in Bruges, the Duke and Duchess and their entourage embarked on a tour of Burgundian territories that included Arras, where the tapestries were most likely made over a period of years (Taylor 32-36).

The Burgundian court gathered in Arras again during the summer of 1435, to welcome dignitaries from England and France to a peace conference (Taylor 72). Both women depicted in the tapestry wear wide belts at a high waistline, and gold necklaces layered over white linen collars. The collars are probably stitched onto partlets, like the one seen in Falconry (Fig. 3). Their headdresses illustrate the two main types worn in northern Europe: the huves headdress made of linen veils suspended over wires (Van Buren and Wieck 308), worn by the woman in blue, and the bourrelet, the padded roll headdress (Boucher 442) worn by the woman in red. Both types of headdress rested upon the “pair of temples” hairstyle, in which the hair was bundled into two tall cones over the temples (Van Buren and Wieck 317-318). While these elements were not new in the 1430s, their proportions and decoration continued to evolve. The bourrelet seen here is heart-shaped, dipping down in the front and curving more sharply to meet the sides of the face. The huves headdress displays a new detail: the long pins that were necessary to hold the layers of linen in place have a new prominence as decorative accessories made of gold or gilded metal. A less elaborate version can be seen in a Rogier van der Weyden portrait (Fig. 6).

Fig. 2 - Rogier van der Weyden (Belgian, 1400-1469). Portrait of a Woman with a Winged Bonnet, 1430. Oil on panel; 47 x 32 cm (18.5 x 12.5 in). Berlin: Gemäldegalerie. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). The Devonshire Hunting Tapestry: Falconry, 1430s. Tapestry-woven; 445 x 1075.9 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.202-1957. Accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax payable on the estate of the 10th Duke of Devonshire and allocated to the Victoria and Albert Museum. Source: V&A

Fig. 8 - Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, 1390-1441). The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434. Oil on oak; 82.2 x 60 cm (32.4 x 23.6 in). London: The National Gallery, NG186. Source: The National Gallery

The Devonshire Hunting tapestries represent the most elaborate fashions of this decade (Fig. 7). A more restrained, but no less luxurious version of Burgundian fashion is shown with great precision in the famous Arnolfini Portrait, an oil painting by Jan van Eyck, who signed and dated it in 1434 (Fig. 8). The subjects of the painting were not aristocrats, but a wealthy merchant, believed to be Giovanni Nicolao Arnolfini, and his wife. The Arnolfini family were originally from Lucca, the leading Italian silk-weaving center in the previous century; from 1419, they were established in Bruges as dealers in cloth and other luxury goods (Koster). The wife in the portrait wears a blue silk dress under a green wool houppelande lined in white fur.

The signs of luxury in her attire are discreet but unmistakable; the sleeves of her dress end in bands embroidered with gold, and her belt is similarly decorated. She wears a doubled gold necklace and two gold rings, but the greatest luxury is seen in the houppelande, flowing in abundant folds of fine wool to trail on the floor. Green was an expensive color to produce since it required over-dyeing yellow with blue (St. Clair 214). As if to consume as much of this expensive fabric as possible, the houppelande was made with bag sleeves that hang nearly to the floor and are decorated with strips of the green wool that have been pinked, folded, and twisted to create a richly contrasting texture to the otherwise silky smooth wool. This is a more intricate form of the dagging technique seen in earlier decades (Van Buren and Wieck 302).

The portrayal of the wife in the Arnolfini portrait illustrates how fashion reinforced the contemporary ideal of beauty. Above her plucked hairline, her hair has been arranged in the “pair of temples” style; the cones of hair are edged with a narrow braid and held in place by a fine, nearly invisible linen or silk hairnet called a crispin (Van Buren and Wieck 160). The headdress on top consists of five layers of linen, each with crimped edges. Van Eyck portrayed his wife Margareta wearing a similar headdress in 1439, with a black silk crispin covering her hair (Fig. 9). Although the white linen veils (Fig. 10) are not suspended on a towering scaffolding of wires, as in the aristocratic huves style, the layers of white linen magnify the apparent size of the head, in proportion to the narrow shoulders and small breasts. In the Arnolfini portrait, we can appreciate how the high waistline elongates the lower body and how the gesture of lifting the extra length in the houppelande creates the illusion of a large, rounded abdomen.

Fig. 9 - Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, 1390-1441). Portrait of Margareta van Eyck, 1439. Oil on panel; 32.6 x 25.8cm. Bruges: Groeningemuseum, 0000.GRO0162. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 10 - Robert Campin (French, 1378-1444). A Woman, 1435. Oil and egg tempera on oak; 40.6 x 28.1 cm (15.9 x 11.1 in). London: The National Gallery, NG653.2. Source: The National Gallery

Fig. 11 - Antonio Pisanello (Italian, 1395-1455). Portrait of an Este Princess, ca. 1433. Oil on poplar; 43 x 30cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, RF 766. Source: Louvre

Fig. 12 - Antonio Pisanello (Italian, 1395-1455). Head of a Young Woman, (Study for the fresco St. George and the Princess, Pellegrini Chapel, San Anastasia, Verona), ca. 1434-8. Pen and ink; 24.5 x 18.4 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, Inv. 2343 (recto). Source: Louvre

Fig. 13 - Antonio Pisanello (Italian, 1395-1455). Two Men and a Woman Wearing Long Houppelandes, ca. 1438-40. Pen, ink, watercolor; 23 x 18cm. Bayonne: Musée Bonnat-Helleu. Source: MBH

While fashion was helping women to achieve ideal beauty in northern Europe, a new and different ideal, influenced by classical antiquity, was emerging in Italy. Pisanello portrayed a member of the d’Este family of Ferrara wearing a dress (gamurra) and houppelande (cioppa or pellanda) with pleats arranged to look like the flutings of classical columns (Fig. 11). Embroidered on the houppelande’s hanging sleeve is a pearl-studded vase, resembling a silver vessel from an ancient Roman trove (see British Museum object 1866,1229.6). This emblem perhaps signifies that the young woman had received a prestigious humanist education in Greek and Latin. Her hairstyle, held in place with strips of linen, is another allusion to antiquity. If it is not the sitter’s own, exposed hair, it may be an example of the balzo, a headdress worn by Italian women during this decade. The balzo was a structure of wire or willow covered with fabric or hair (Pipponier and Mane 95); a larger example is shown in a drawing by Pisanello (Fig. 12). Like the headdresses worn in northern Europe, the balzo made a woman’s head look bigger, an effect that was heightened by plucking the eyebrows and hairline. The balzo’s bulbous shape crowned the elongated silhouette created by a woman’s high-waisted houppelande, trailing on the ground (Fig. 13).

Fashion Icon: PISANELLO (Antonio di Puccio Pisano, c. 1395-1455)

The artist known as Pisanello (Fig. 1) holds a special place in the history of fashion. He was born either in Pisa, where his father Puccio di Giovanni di Cereto was a cloth merchant, or in Verona, his mother’s native city, where he first studied art. From 1415 to 1422, he worked in Venice as an assistant to Gentile da Fabriano, master of the International Gothic style, on frescoes decorating the Doge’s Palace that were later destroyed. Pisanello would share Gentile da Fabriano’s refinement, attention to detail and love of sumptuous textiles adorned with silver and gold.

In 1422 he bought a house in Verona, but spent the rest of the decade working for the ruling families of Milan, Mantua and Ferrara, In 1431, Pisanello travelled to Rome to complete frescoes in the Church of St. John Lateran that had been started by Gentile da Fabriano, who had died in 1427. By 1433 he had resumed his rounds of northern Italian courts, painting frescoes and portraits and serving as courtier and general artistic adviser.

The Portrait of an Este Princess (Fig. 11 in womenswear), in which he related the fashions of his own day to the dress of antiquity, is evidence of the influence of ancient art that he had absorbed in Rome. Although many of Pisanello’s paintings were later damaged or destroyed, a significant number of his drawings survive (Chiarelli and Pollard). Several drawings suggest that he also designed textiles and jewelry, and some may be designs for fashions to be worn at court festivities (Monnas 52-54). Rendered with his characteristic delicacy of line, in the three-quarter view that will become standard for fashion illustration, Pisanello’s graceful figures wear elaborate and imaginative houppelandes and capes that extend the boundaries of fashion (Fig. 13 in Womenswear).

One drawing (Fig. 2) shows a man and woman transformed into exotic birds with plumage of pink and green. Such drawings, which include seamlines and other construction details, could be turned over to a tailor to be executed. Centuries later, they inspired the design of a court mantle by Rosa Genoni (1867-1954), a dressmaker, teacher of costume history, and advocate for Italian fashion (Fig. 4).

In addition to creating what may be the earliest surviving fashion designs, Pisanello turned Italian fashion towards antiquity as a source of inspiration. At the end of the decade, he invented a new genre, the cast bronze portrait medal, with antecedents in ancient coins (Chiarelli and Pollard). Pisanello’s multiple talents and skills made him highly sought-after by powerful patrons; because he traveled widely, ending his career in Naples, his influence spread throughout Italy.

Fig. 1 - Antonio Marescotti (Italian). Antonio Pisano, called Pisanello, ca. 1440. Bronze; 5.81cm in diameter (2 5/16 in). Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1957.14.624.a. Samuel H. Kress Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 2 - Antonio Pisanello (Italian, 1395-1455). Gentleman and Lady in Court Costume, ca. 1438-40. Ink and watercolor on parchment; 273 x 196cm. Chantilly: Musée Condé, DE4496. Source: Rmn-GP

Fig. 3 - Rosa Genoni (Italian, 1867–1954). “Pisanello” court mantle, 1906. Embroidered silk satin and silk velvet. Florence: Palazzo Pitti Galeria del Costume. Source: Europeana

Menswear

During this decade men continued to wear underwear consisting of a shirt and a pair of drawers made of undyed linen (Piponnier and Mane 87). An example of a shirt can be seen in the Swan and Otter Hunt tapestry in the Devonshire Hunting series, worn by a young boy who is teetering on a collapsing ladder (Fig. 1). A drawing by Pisanello (Fig. 2) shows us the next layer of clothing: A pair of hose, laced to the main upper body garment, the doublet. The hose was typically made of woven fabric, usually wool for its natural elasticity. Doublets, which fastened down the front with laces or buttons, were lined in linen for a close fit and to protect the more expensive outer fabric, which could be wool or silk (Piponnier and Mane 68). Pisanello’s drawing shows hose laced to the doublet at the sides through paired eyelets; the doublet is fitted, with a seamline at the waist, and the sleeves are each cut in two pieces that follow the curve of the arm.

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Detail from the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries: Swan and Otter Hunt, 1430s. Tapestry woven with wool warp and weft; 424 x 1118 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T. 203-1957. Source: VAM

Fig. 2 - Antonio Pisanello (Italian, 1395-1455). Study of a Young Man with his hands tied behind his back, ca. 1434-8. Pen and ink; 26.8 x 18.6 cm. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, D 722. David Laing Bequest to the Royal Scottish Academy. Source: NGS

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Detail from the Falconry Tapestry, 1430s. Tapestry; 445 x 1075.9 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.202-1957. Source: VAM

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Detail from the Swan and Otter Hunt Tapestry, 1430s. Tapestry woven with wool warp and weft; 424 x 1118 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T. 203-1957. Source: VAM

As in earlier decades during this century, fashion change was most evident in outer garments and accessories. Most men’s houppelandes in the 1430s were the shorter form of the garment, also called the haincelin, that was rarely longer than a few inches below the knee. A simple version can be seen in the Falconry tapestry, worn by a country musician (Fig. 3). This figure also wears red hose and a matching red chaperon, a headdress made of draped fabric that could have a long, trailing end called a cornet (Van Buren and Wieck 300).

The Devonshire Hunting tapestries and other sources from this decade depict many more elaborate houppelandes made of brightly colored wool or richly patterned Italian silks. What most of them have in common is a voluminous, loose fit. In Otter and Swan, two men stand next to two women in towering bourrelet headdresses (Fig. 4). The man on the left wears a two-toned red houppelande (probably meant to represent a silk damask or a voided velvet), trimmed with fur and featuring sleeves in the poke style. The man on the right wears an alternative outer garment, the huque or journade, made of two widths of fabric joined at the shoulders, revealing the sleeves of the doublet underneath (Van Burne and Wieck 308). Under his blue huque, this man’s doublet is of floral-patterned gold and black silk.

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Detail from the Boar and Bear Hunt Tapestry, 1425-1430. Tapestry woven with wool warp and weft; 1023 x 385.4cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.204-1957. Source: VAM

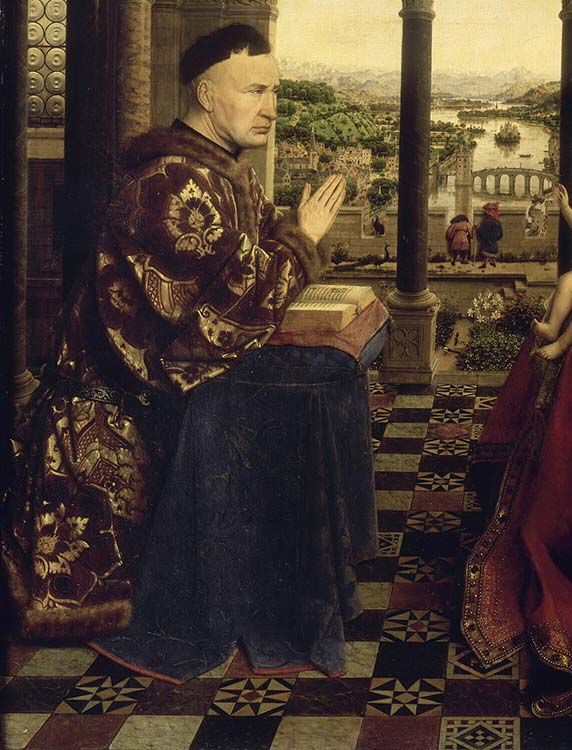

Fig. 6 - Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, 1390-1441). Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, 1435. Oil on oak; 66 x 62 cm (25.9 x 24.4 in). Paris: The Louvre, Inv. 1271. Source: Louvre

A wider huque, made of a boldly patterned blue fabric, trimmed or lined in fur and with deeply dagged edges, can be seen in Boar and Bear (Fig. 5). The doublet underneath is of a greenish-blue, but it appears to have one red sleeve. Parti-coloring, the practice of using contrasting colors or patterns for the different parts of a garment, was well established during this decade (Piponnier and Mane 133). Like his companion to the left, the man’s hose is parti-colored red and white, with red laces connecting the hose to the doublet. Although hunters are seen wearing brown leather boots are throughout the tapestries, both of these men wear soled hose, that eliminated the need for shoes, and both wear red chaperons, but they are draped in different ways around the foundation of a padded roll, as in women’s bourrelet headdresses. Men also wore a variety of hats during this decade, such as the brimmed hat with a flaring crown seen in figure 4, that appears to be of woven straw. The “bag hat” with a soft crown made of fabric (Fig. 1 in fashion icon) was not a new style during this decade, though it was somewhat taller and narrower (Van Buren and Wieck158). Under their headgear, most men during this decade, even in Italy, wore their hair closely cropped in the Burgundian “bowl” style (Van Buren and Wieck, 311).

The tapestries that the duke of Burgundy commissioned and collected in great numbers, and displayed publicly during his frequent travels, reflect the competitive pursuit of luxurious display at his court (Vaughan 56). Burgundian fashion continued to influence the rest of Europe, but its most luxurious materials came from Italy.

In the Madonna of Chancellor Rolin (Fig. 6), the duke’s most trusted government official, Nicolas Rolin, wears a houppelande made of a magnificent dark green Italian silk velvet brocaded with gold (Fig. 7). Jan van Eyck depicted in great detail, including the sparkling loops of gold (“alluciolato” wefts) woven in the areas of velvet pile, which helps textile historians date this new technique to the 1430s (Monnas 113). The houppelande is trimmed or entirely lined in fur and has the voluminous curved poke sleeves and low-slung belt that were fashionable until the final years of the decade, when, sleeves became straighter and belts were placed at the natural waistline (Van Buren and Wieck 158). At the neckline of Chancellor Rolin’s houppelande, we can see the black doublet worn underneath.

Van Eyck portrayed the textile merchant Giovanni Arnolfini (Fig. 8) dressed in similar Burgundian fashions made of Italian luxury materials, but the luxury is in a lower key. As Duke Philip the Good himself demonstrated with his customary black attire (Piponnier and Mane 73), black and other dark colors were particularly elegant and made a powerful statement. Over a black doublet and black hose, Arnolfini wears a dark reddish brown huque, lined in fur. Van Eyck has depicted the materials of the doublet and huque as lustrous, with variations in the depth of color, indicating that both textiles were silk, possibly silk damask or pile-on-pile velvet for the doublet, and a solid velvet for the huque. Arnolfini’s wide-brimmed hat has a flared crown and is made of finely woven straw, like the hat seen in figure 4, only dyed black. His wooden pattens, shoes that before the 1440s were only worn outdoors (Van Buren and Wieck 164), are discarded at his feet. His wife’s red shoes are in the background. A restrained interpretation of court fashions was appropriate for a man from the city-dwelling merchant class, but as in the wife’s dress, the signs of wealth and status are impossible to miss. At the center of the portrait, Arnolfini reaches for his wife’s outstretched hand, and we see that the sleeves of his doublet end in bands embroidered with silver thread, corresponding to the sleeves of her dress, embroidered with gold. As in women’s fashion, sleeves were particularly favored for the display of embroidered personal emblems; one reason why the huque, which in Italy was called the giornea, was increasingly fashionable is that it allowed a view of the doublet sleeves (Frick 192).

Fig. 7 - Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, 1390-1441). Detail from Virgin and Child with Chancellor Rolin, 1430-4. Oil on wood; 66 x 62cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, Inv. 1271. Source: Louvre

Fig. 8 - Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, 1390-1441). The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434. Oil on oak; 82.2 x 60 cm (32.4 x 23.6 in). London: The National Gallery, NG186. Source: The National Gallery

In 1439, Florence enacted a sumptuary law that confined embroidery and trimming to sleeves (Frick 197) but other voices were raised questioning the value of ornament in dress wherever it was placed. Leon Battista Alberti’s I libri della famiglia, a how-to book for the management of the household and family, was published in 1433. Alberti advised the head of a family to be very concerned about dress and to ensure that clothing of good quality was properly cared for. The character Uncle Giannozzo tells his nephews:

“We want to have beautiful clothes. Since they do us honor, we too should have some consideration for them.” (Frick 80)

However Alberti was not in favor of elaborately decorative clothing:

“the slashed garments and embroidery that one sees on some people have never seemed attractive to me except for clowns and trumpeters.” (Frick 82)

What was refreshingly new about his critique of fashion was that it was not on moral or economic, but rather on aesthetic grounds. Alberti did not argue that the fashion of his day was immoral or wasteful, but rather that it was not as beautiful as it could be, if only it were simpler, and closer to the dress of antiquity.

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Detail from the Boar and Bear Hunt Tapestry, 1425-1430. Tapestry woven with wool warp and weft; 1023 x 385.4cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.204-1957. Source: VAM

Nevertheless, in the 1430s there continued to be many examples of men’s dress adorned with metallic embroidery, such as a chaperon trimmed with gold-tipped ribbons and gold leaves, seen in figure 9, and a houppelande with one sleeve covered with golden teardrops (Fig. 5 in womenswear).

Men’s low-slung belts could be made of gold or gilded leather, and they wore gold necklaces festooned across the shoulders, some with dangling pendants (Fig. 5).

At the court of Burgundy the most sought-after jewel was the collar and pendant of the Order of the Golden Fleece, the new chivalric order created by Duke Phillip the Good. It was announced on January 10, 1430, at the culmination of the festivities to celebrate the Duke’s marriage to Isabella of Portugal. At first limited to twenty-four noblemen chosen by the Duke, the Order of the Golden Fleece was intended to be a loyal inner circle that would bind the disparate Burgundian territories together (Vaughan 160-161). Members wore their ceremonial red robes only for their annual meetings, but the jeweled insignia of the Order was supposed to be worn at all times, even into battle (Vaughan 84-85). In the following decade, along with the growing preference for black, the Golden Fleece would become symbolic of Burgundian elegance.

CHILDREN’S WEAR

In the 1430s very young children, just out of their swaddling bands, were dressed in tunics of linen or wool, layered one over the other according to the season. As they grew older, their clothes became more fitted and more fashionable. Children are commonly shown in art wearing fewer layers of clothing and fewer accessories than adults. One of the boys raiding the swans’ nest in Swan and Otter Hunt (Fig. 1) wears only his shirt; the slightly older boy wears a long red doublet with fashionable full sleeves. The doublet is unlaced at the neckline and hem, allowing glimpses of his underwear and the garment’s linen lining. Both boys would wear hose if fully dressed.

Nearby is a teenage girl in a light blue dress, handing a swan to a woman in a boldly patterned houppelande. Her dress is fashionably tight-fitting, but in contrast to the adult woman, she wears no headdress; her hair flows freely down her back, the sign of an unmarried girl (Van Buren and Wieck 180).

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Detail from the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries: Swan and Otter Hunt, 1430s. Tapestry woven with wool warp and weft; 424 x 1118 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T. 203-1957. Source: VAM

References:

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume in the West. New York: Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/824293869.

- Cavallo, Medieval Tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/464222703.

- Chiarelli, Renzo and J.G. Pollard. “Pisanello.” Grove Dictionary of Art. Oxford Art Online, 2003. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:3206/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T067876.

- Evans, Joan. Dress in Medieval France. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/939659457.

- Frick, Carole Collier. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes and Fine Clothing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62133195.

- Harbison, Craig, “Sexuality and Social Standing in Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Double Portrait.” Renaissance Quarterly 43: 2 (Summer 1990) 249–291. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2862365.

- Herald, Jacqueline. Renaissance Dress in Italy, 1400-1500. London: Bell & Hyman, 1981. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/492385048.

- Koster, Margaret L. “The Arnolfini Double Portrait: A Simple Solution.” Apollo Sept. 1, 2003. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/The+Arnolfini+double+portrait%3a+a+simple+solution.-a0109131988.

- Monnas, Lisa. Merchants, Princes and Painters: Silk Fabrics in Italian and Northern Paintings 1300-1550. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/442203691.

- National Gallery of Art, London. “The Arnolfini Portrait.” https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jan-van-eyck-the-arnolfini-portrait.

- Piponnier, Françoise and Perrine Mane, Dress in the Middle Ages. Tr. by Catherine Beamish. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/943018667.

- St. Clair, Kassia. The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1054402560.

- Taylor, Aline S. Isabel of Burgundy: The Duchess who Played Politics in the Age of Joan of Arc, 1397-1471. London: Madison Books, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/669330920.

- Van Buren, Anne and Roger S. Wieck. Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/742330843.

- Vaughan, Richard. Phillip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy. Vol. 3 of The Dukes of Burgundy. Woodbridge [UK]: Boydell Press, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1040841568.

- Victoria and Albert Museum. “The Devonshire Hunting Tapestries.” https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-devonshire-hunting-tapestries.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1430-1439

Rulers:

- England

- Henry VI (1422-1461)

- France

- Henry VI (1422-1453) [disputed]

- Charles VII (1422-1461)

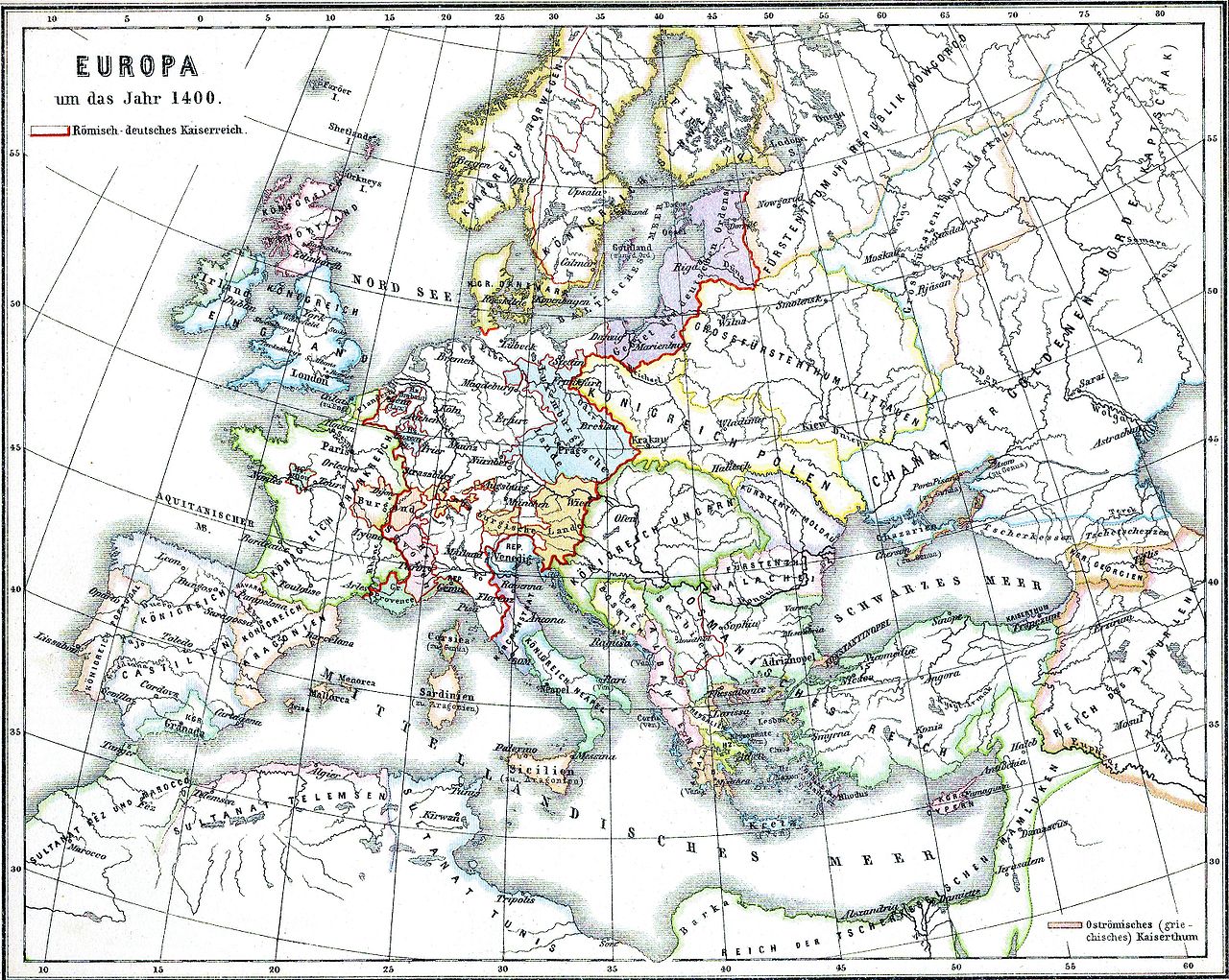

Europa 1400. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Events:

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 15th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.