OVERVIEW

During the 1860s, the cage crinoline allowed women’s skirts to reach their apex in size, while menswear relaxed into wide, easy cuts. Advances in technology, such as the sewing machine and aniline dyes, and the rise of Parisian couture, beginning with the House of Worth, changed the fashion landscape.

Womenswear

Fig. 1 - Maker unknown. Cage Crinoline, ca. 1865. Steel-wire hoops, linen tapes. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC3863 81-19. Source: Kyoto Costume Institute

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (Probably American). Day dress, 1860-1862. Printed wool, silk braid. Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1978-110-25. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Stanley W. Root, Jr., 1978. Source: The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (American). Afternoon dress, ca. 1865. Silk, metal. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.1000a, b. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (British). Dress, 1868-1869. Silk, wool, glazed cotton, whalebone. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.6 to C-1937. Given by Miss E. Beard. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 5 - George Washington Wilson (Scottish, 1823-1893). The Crown Princess of Prussia (Princess Royal of England) and Prince Henry, October 1863. Albumen print; 10.6 x 7.7 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2900819. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Womenswear consisted of a fitted bodice, a variety of sleeve styles, and a floor-skimming wide skirt. The cage crinoline was worn over a chemise, drawers, and a corset. Corsets shortened as there was no need to confine the hips (Tortora 361). In general, corsets were not tight-laced during this period; the sheer size of the skirts made waists appear small by comparison (Mitchell 94). The location of the waistline moved upwards during the 1860s, creating a short-waisted effect that would carry into the bustle silhouette of the 1870s. Around 1865, it also became common for the topmost skirt layer to be drawn upwards to reveal the underskirt or petticoat beneath, particularly in walking dresses or those worn for sporting (Fig. 5). Petticoats, now often exposed, could then be found trimmed with ruffles along the hem and made in bold colors and patterns (Thieme 51). This double-skirted appearance became more common late in the decade, as looped overskirts and long basques came into fashion (Cunnington 230-235).

Fig. 6 - Photographer unknown. Sarah Parker Remond, ca. 1865. Albumen print. Salem, MA: Peabody Essex Museum, PH322. Gift of Miss Cecelia R. Babcock. Source: National Park Service

Throughout the decade, daytime bodices featured long sleeves and high necklines. Sleeves were dropped, set into an armscye below the natural shoulder. The wide, bell-shaped “pagoda” sleeves of the 1850s, always filled with large, ballooning undersleeves called engageantes, continued to be fashionable (Fig. 6). More frequently, sleeves of the 1860s began to close at the wrist and took on many varieties. The most common was a “jacket” or “coat” sleeve resembling a man’s coat sleeve, featuring a distinctive slight forward curve in the cut (Fig. 7) (Severa 194-197). Detachable collars and belts usually completed a day dress (Tortora 363).

Fig. 7 - Legastelois (French). The Fashions Expressly Designed And Prepared For The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine., January 1864. Print; (8 x 5 in). New York: The New York Public Library, PC COSTU-186-En. Source: The New York Public Library

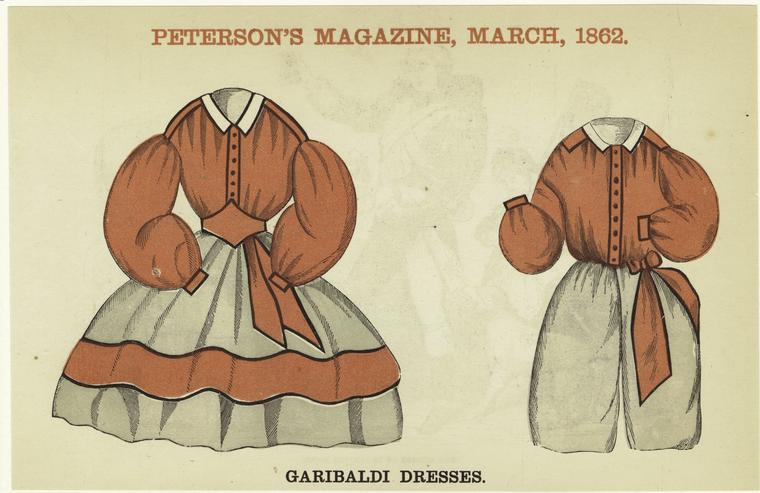

In the 1860s, a trend for skirts paired with shirtwaists, or blouses, as opposed to a matching bodice became prevalent for casual daytime wear, especially among young women. The most important type of shirtwaist was the “garibaldi” inspired by the military uniforms of Italian freedom fighter Giuseppe Garibaldi (Severa 197). Traditionally made in a scarlet merino wool with black braid and buttons, it featured a high neckline and full sleeves gathered into a tight cuff (Fig. 8). The garibaldi shirt was also seen in black wool or white cotton (Cumming 90). Another military-inspired women’s fashion was the “Zouave” jacket borrowed from the Algerian Zouave troops who fought in the Italian war of 1859. The short, collarless Zouave jacket featured rounded borders trimmed in soutache braid, and fastened at the neck (Fig. 9). It was frequently paired with a garibaldi (Cunnington 211; Tortora 366).

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown. Garibaldi Dresses, March 1862. Print; (5 1/2 x 8 1/2 in). New York: New York Public Library, PC COSTU-186-Am. Source: New York Public Library

Fig. 9 - Auguste Toulmouche (French, 1829-1890). A Love Letter, 1863. Oil on canvas; (24 x 19.8 in). Private Collection. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (French). Evening dress, 1860-1861. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.43.7.2a, b. Gift of Estate of Mrs. Robert B. Noyes, 1943. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (Probably American). Dress: Bodice, Skirt, and Belt, 1866-1868. Silk satin, black cotton lace. Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1997-80-1a--c. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. W. W. Keen Butcher, 1997. Source: The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Fig. 12 - Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910). James Pinson Labulo Davies and Sarah Forbes Bonetta, September 15, 1862. Albumen print; (4 1/4 x 5 1/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG Ax61385. Purchased, 1904. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 13 - Artist unknown (French). Modes de Paris, 1868. Print engraving; 27.5 x 18 cm. Seattle: University of Washington, COS177. Source: University of Washington

In the evening, the neckline of dresses dropped off-the-shoulder and could be straight or en coeur (dipped in the center). The neckline was often trimmed with a bertha, a folded band of fabric, usually pleated silk or a fine lace (Fig. 10). Sleeves were very short, sometimes mere straps across the shoulders (Tortora 365). Regarding outerwear, shawls continued to be favored, especially as the wide skirts were a perfect surface upon which to display a large Paisley or “India” shawl. However, jackets were increasingly worn, particularly toward the end of the decade (Severa 203-204). The paletot (Fig. 5), a three-quarter length jacket, featured loose sleeves and draped gently from shoulder to hem (Cumming 146). Mantles were another option usually worn full and often trimmed with tassels and braid (Tortora 366).

Technology and invention was evident in the fashion of 1860s women. Firstly, the use of the sewing machine grew exponentially, especially after the Civil War broke out in the United States instantly causing an enormous demand for ready-to-wear military uniforms (Tortora 358). The Singer Company, founded by Issac Singer in the 1850s, was the largest manufacturer of sewing machines in the world by 1860 and specifically created and marketed versions for domestic use (Brittanica). Soon, many women were using the sewing machine in their homes, and the ready-to-wear industry was expanded thanks to the efficiency that the sewing machine could provide. Arguably, the popularity of ready-made cloaks and cage crinolines were in part due to the sewing machine as it allowed both to be made quickly and cheaply (Tortora 358). Secondly, synthetic dyes were becoming all the rage (Fig. 11). The first one, a vivid purple hue named “mauveine,” had been invented by William Henry Perkins in 1856, and more synthetic shades quickly followed (Tortora 361). By the mid-to-late 1860s, the trend for vivid, sometimes garish colors, often in contrasting combinations, was firmly established (Cunnington 206-207).

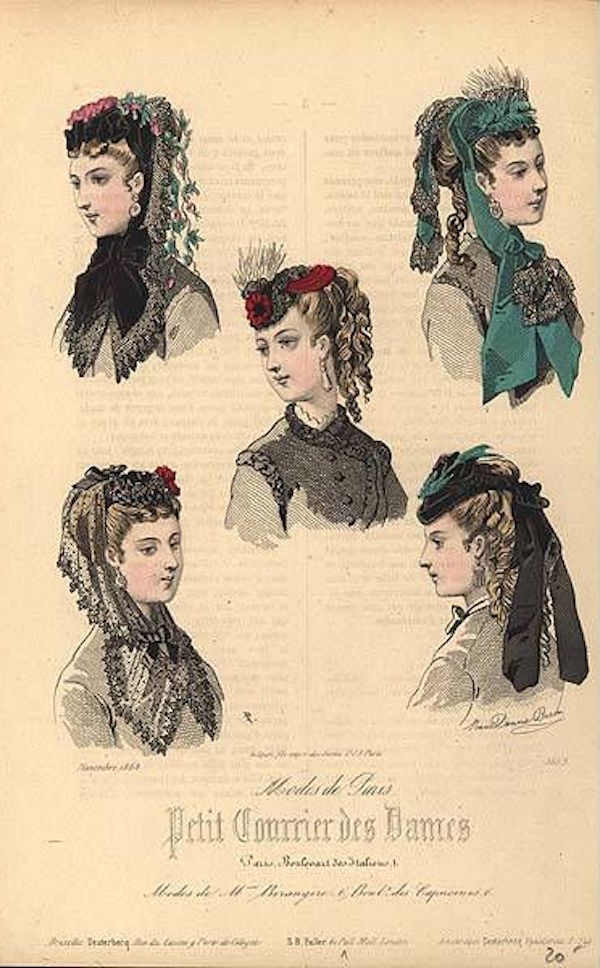

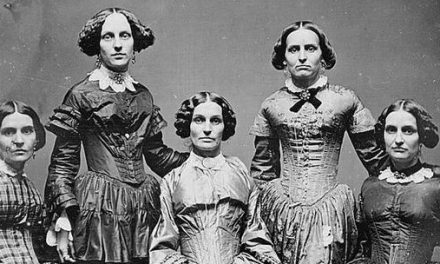

In the early 1860s, women wore their hair parted in the center and smoothly combed back into a chignon, sometimes featuring small curls or braids above the ears (Cunnington 244). The hair net, or snood, was an all-important accessory, usually made of chenille yarns or silk, worn looped around the chignon at the back (Fig. 12). Late in the decade, hairstyles became more complicated; curls were left loose in the back underneath ever larger arrangements of braids and chignons (Fig. 13). False hair became commonplace, sold in puffs, curls, and braids. As hairstyles grew in size and complexity, the snood fell out of fashion (Severa 205-206). Throughout the decade, both the bonnet, defined by its strings tied around the chin, and the hat, which lacked such strings, were worn. In previous years, a bonnet was considered the more formal, modest choice; there had been a certain propriety about whether one wore a bonnet or a hat. During the 1860s, these rules began to fade from relevancy, a trend that continued into the 1870s (Cunnington 238). Bonnets shrank to a small depth, and were worn tipped back on the head. Hats, meanwhile, were worn at the center of the head, and were generally low-crowned, round, and could feature a wide or narrow brim. Around 1868, as hairstyles became high and cascading down the back, the hat was pushed forward to lean over the forehead (Severa 206-207). For formal evening occasions, hair ornaments of jewel, flowers, or fruit were worn (Tortora 367).

The 1860s witnessed the rise of one of the most important characters in nineteenth-century fashion, Charles Frederick Worth, who is celebrated as “the father of haute couture” (Trubert-Tollu 10; Perrot 41). An Englishman who moved to Paris as a young man, Worth worked in the fabric houses and then the well-established Maison Gagelin. In 1858 he opened his own fashion house, alongside his partner Otto Gustave Bobergh, who handled the administration of the business. By 1860, through deliberate outreach and clever marketing, Worth had been introduced into the imperial court circles and began dressing the most elite of French society, including Empress Eugenie (Coleman 12-13). Throughout the 1860s, the House of Worth enjoyed a meteoric rise and was soon counting aristocratic women from across Europe and wealthy socialites in America as his clients (Tortora 354). Worth’s designs were known for their distinctive fabrics and luxurious trims, excellent fit, and historical inspiration, especially seventeenth- and eighteenth-century revivals (Fig. 14) (Coleman 47; Met). The House of Worth led fashion throughout the rest of the century and into the twentieth. The authors of The House of Worth: 1858-1954, The Birth of Haute Couture wrote that Worth was:

“a touchstone for the radical transformation of the world of ladies’ dressmaking that took place from the 1860s, pairing the traditional work of seamstresses with the practices of the ready-made garment industry and the marketing methods of Paris fashion houses…Applying his innate sense of aesthetics and love of art to his couture work, [Worth] was able to marry the exquisite taste of Paris fashions…with the sophisticated commercial and marketing methods developed by his British counterparts.” (10)

Fig. 14 - Charles Frederick Worth (British, 1825-1895). Evening dress, 1866-1868. Silk. Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1996-19-3a,b. 125th Anniversary Acquisition. Gift of the heirs of Charlotte Hope Binney Tyler Montgomery, 1996. Source: The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Fashion Icon: Princess Pauline von Metternich (1836-1921)

Fig. 1 - André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819 - 1889). Princess de Metternich, 1864. Albumen print. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XD.379.169. Source: The J. Paul Getty Museum

Fig. 2 - Franz Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). Princess Pauline von Metternich, 1860. Oil on canvas; 89.5×77.8 cm. Private Collection. Source: Wikipedia

Princess Pauline von Metternich was a glittering member of the French imperial court during the 1860s, and arguably precipitated Worth’s rise to fame, becoming one of his first clients and introducing him to Empress Eugenie. Born in Vienna in 1836, Pauline became the young wife of the Austrian ambassador to France, Prince Richard von Metternich in 1856. They arrived in Paris in 1859, where she quickly established herself as a fashionable lady, one who compensated for her supposedly plain appearance by cultivating a zest for art, music, and lavish parties (Trubert-Trollu 32). More importantly, Pauline was always seen in the latest mode (Figs. 1-2), often ahead of the winds of fashion; it is said that she began to loop up her skirts to reveal a petticoat as early as 1859, a practice that would not become widespread until the mid-1860s (Thieme 51). She was a close friend of Empress Eugenie, and the emperor considered her invaluable in demonstrating the luxury and fashionability of the French court, a sign that France was regaining its prestige.

In 1860, Worth’s wife, Marie, was on a mission to gain clients for her husband from the highest in French society (Coleman 13). Pauline described in her memoirs how her maid received a book of designs from Marie, who was boldly imploring Pauline to examine them and offered that her husband would make her a gown at any price. Impressed with the artistry of the designs, Pauline ordered two gowns for only 600 francs. When she wore her new evening gown, a white tulle confection laden with diamonds and pink daisies, Empress Eugenie immediately requested an introduction to the unknown Englishman who had made it. It was noted in The House of Worth: 1858-1954, that “Worth’s career was thus launched, and never again would the princess be able to have a Worth dress for a mere 300 francs” (34). Even after the fall of the Second Empire in 1871, Pauline’s fashionable influence remained. She continued her patronage of the House of Worth after she and her husband were ordered back to Vienna (Coleman 100). Pauline and Worth remained friends for the remainder of their lives; Worth never forgot that he owed his career to Pauline (Trubert-Tollu 34).

Menswear

“easy to wear but rather shapeless, and because of [its] untailored style, even the dapper mid-Victorian man of fashion known as a “swell” appeared to contemporaries somewhat languid or drooping.” (34)

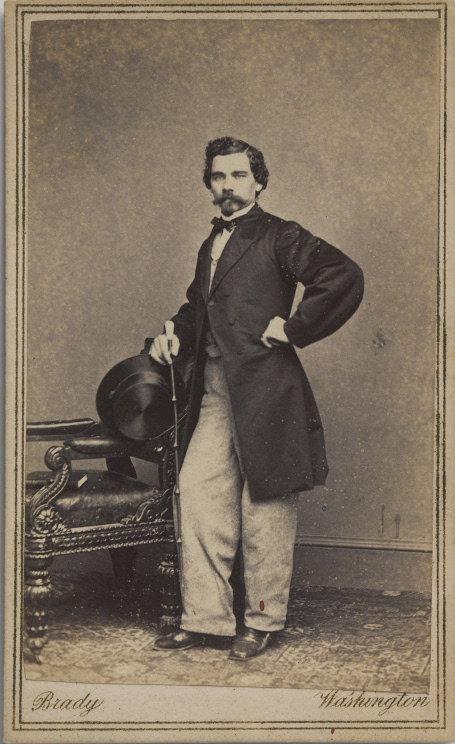

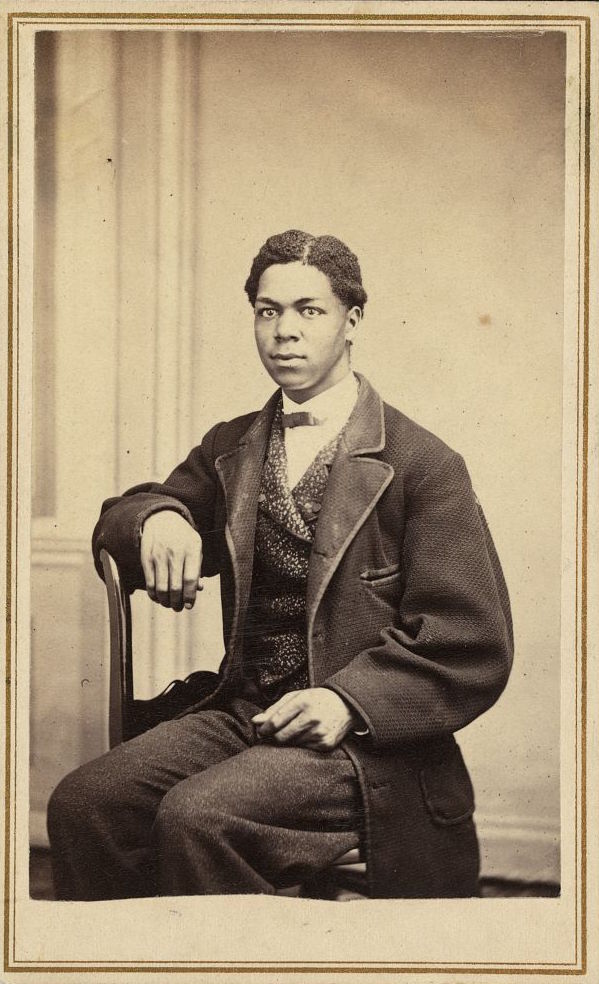

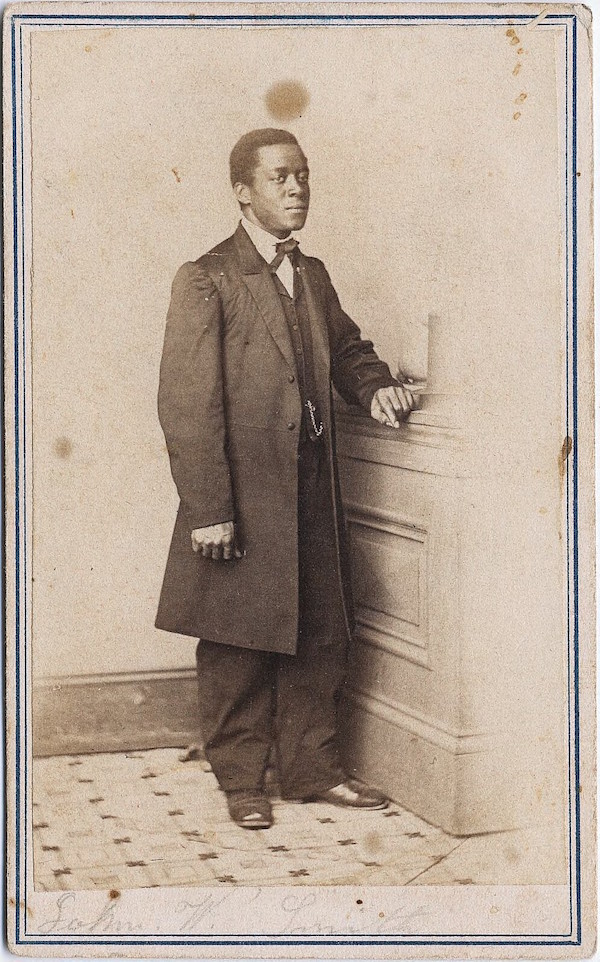

Jackets, of all types, retained the dropped shoulder seam and generously cut sleeves of the 1850s, and extended to thigh-length (Figs. 2-3) (Severa 209). By the late 1860s, the overall silhouette began to slim down and jackets shortened, a trend that continued in the 1870s (Shrimpton 34-35).

As in womenswear, technology had a marked effect on menswear. The sewing machine was quickly creating the ability for much of male clothing to be mass-produced. The Civil War greatly sped up the use of sewing machines; considering the Union army required 1.5 million uniforms a year, there was an overwhelming demand. The number of sewing machines in use doubled from 1860 to 1865 (Tortora 356, 358). Shirts, underwear, accessories, increasingly even trousers and overcoats were made by machine. Brooks Brothers noted in the 1860s, that the creation of an overcoat took six days by hand, but with the assistance of the machine could be completed in three (Severa 208). The Civil War bolstered the ready-to-wear industry in another way when the Union army collected measurements and statistics on adult men. These figures were very useful to manufacturers after the war (Tortora 358).

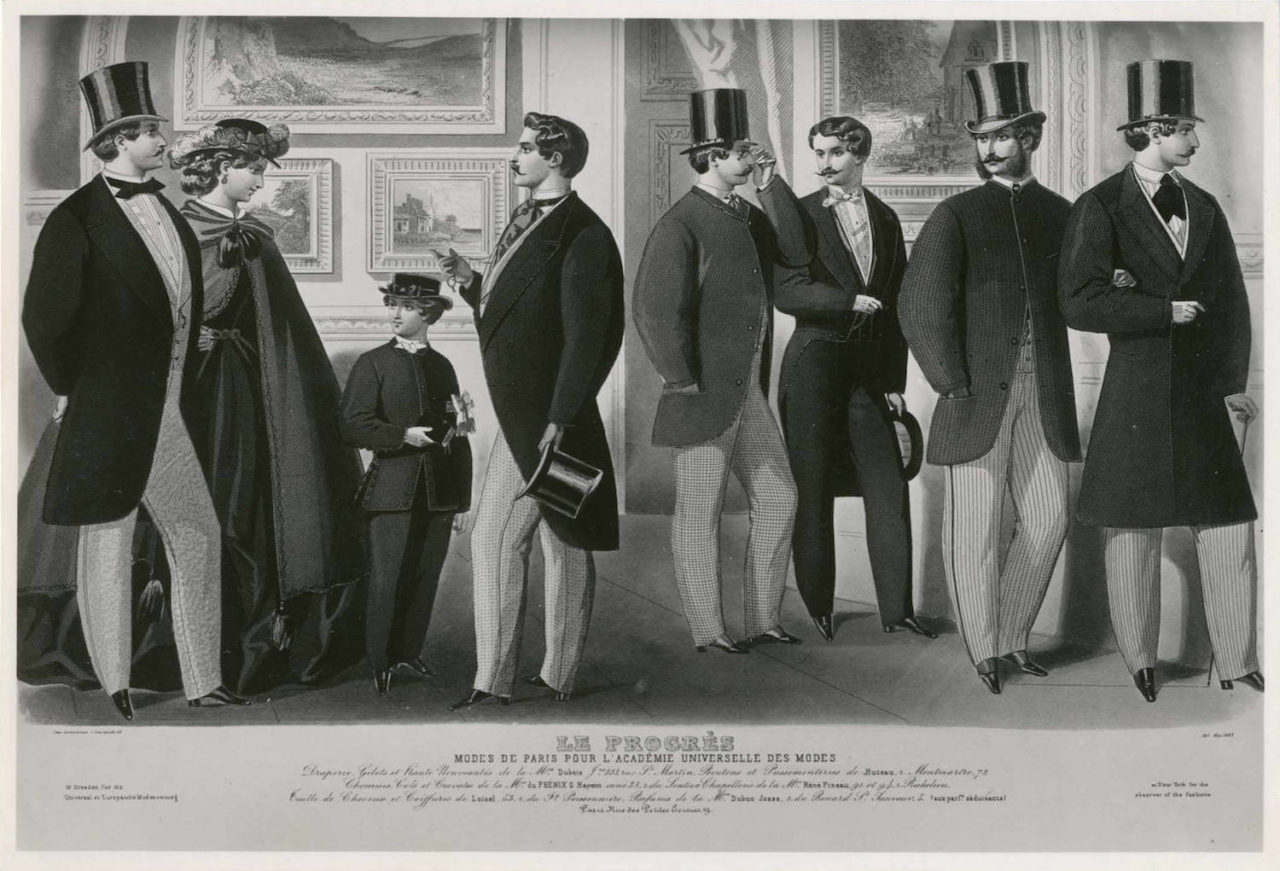

The sack or lounge jacket, straight, loose and lacking a waist seam, was gaining in fashionability and acceptance as casual or even semi-formal daywear. When worn with a matching waistcoat, and contrasting trousers, the sack could be made in a dark wool, or it could be tailored in a three-piece matching light suit (Fig. 4) (Severa 209; Shrimpton 34-35). For more formal, business attire, a man would choose a morning coat, defined by its waistline seam and its cutaway front which became a gentler curve in the 1860s (Cumming 135; Tortora 370). The gentleman second from left in Figure 5 wears a morning coat. Paired with a waistcoat and trousers, the morning coat was often tailored in heavier, dark wools and tweeds. Finally, the black wool frock coat, with its defining waist seam and full skirt (Figs. 1, 6), was increasingly relegated to the more formal daywear occasions (Cumming 87; Severa 209). Trousers, wide and billowing, could be either light or dark, and stripes and checks were sometimes seen, as in Figure 5, though patterns were increasingly rare through the 1860s (Tortora 371; Severa 209). The tailcoat became completely reserved for formal evening occasions in the 1860s, worn with a matching waistcoat and trousers, and a starched ruffled or embroidered white shirt (Tortora 370-371). The gentleman third from right in Figure 5 wears an evening tailcoat suit.

Fig. 1 - Mathew B. Brady (American, 1823-1896). John Mulvaney, ca. 1863. Albumen print; (3 9/16 x 2 3/16 in). Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institute, The National Portrait Gallery, S/NPG.2007.139. Gift of Larry J. West. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 2 - J. N. Ramsdill (American). Three-quarter-length portrait of an unidentified African American man, wearing suit, seated, 1860s. Carte-de-visite photographic print; 10 x 6 cm. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, LOT 14022, no. 88 [P&P]. Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 3 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). The Circle of the Rue Royale, 1868. Oil on canvas; (68.8 x 110.6 in). Paris: Musée d'Orsay, RF 2011 53. Source: WIkimedia

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (British). Sack Suit, 1865-1870. Wool, silk, cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986.114.4a–c. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Trust Gift, 1986. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (French). Le Progrès: Modes de Paris Pour L'Académie Universelle Des Modes, 1863. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

Fig. 6 - Photographer unknown (American). Full length portrait of John W. Smith, ca. 1865. Carte-de-visite photographic print; 10 x 7 cm. New Haven, CT: Yale University: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, 2003888. From the Randolph Linsly Simpson African-American Collection. Source: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library

Regarding outerwear, the chesterfield coat, edged with braid and silk velvet facings (Cumming 46), was a popular form of outerwear, alongside the short, double-breasted reefer (Tortora 371). The top frock and the Inverness, featuring an attached cape, were also fashionable (Laver 205). A cloak, similar to a woman’s mantle, was the appropriate evening outerwear (Tortora 371). Shirts, more often concealed underneath high-buttoned jackets, were now more plain than previous decades. Shirt collars were not particularly high, and often folded down, completed by a variety of ties and cravats. Waistcoats were usually single-breasted and often featured a shawl collar (Severa 209). Figure 3 depicts the various shirt, tie, and waistcoat fashions. Most men held their trousers in place with suspenders; a lovely embroidered pair was considered an appropriate gift to a man from a lady (Tortora 371).

Men wore their hair at ear level, neatly parted and combed to the side; a soft wave was considered attractive (Severa 210). A variety of whiskers were fashionable including trim beards, mustaches, and frequently, long side-whiskers sometimes referred to as “muttonchops” or “Dundreary whiskers” (Fig. 3) (Tortora 371; V&A). The silk top hat remained the predominant choice, reaching tall heights in the early 1860s. It was seen with frock coats, morning coats, and even sack jackets. However, as the decade wore on, the top hat became increasingly formal and began to be reserved for only the frock, morning and tailcoat (Shrimpton 35). The rounded bowler hat was more frequently seen with sack jackets and flat-crowned straws were worn in summer. By the late 1860s, the top hat and the bowler had diminished some in height, as the overall silhouette became more streamlined (Tortora 372).

CHILDREN’S WEAR

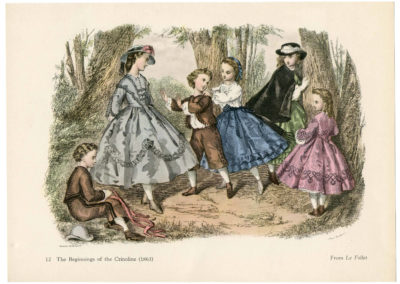

Infants wore long white cotton dresses, short or long-sleeved, until about nine months old when they graduated to shortened dresses. Toddler boys and girls were dressed nearly alike in short-waisted dresses with full skirts until about the age of five or six when boys were breeched (given their first pair of trousers). These dresses could range from strong tartans to delicate calico prints (Fig. 1), the former being slightly more associated with boys’ dresses. Both sexes could also wear plain-colored dresses edged in soutache braid, echoing an adult trend towards military-style trim (Fig. 2) (Severa 210).

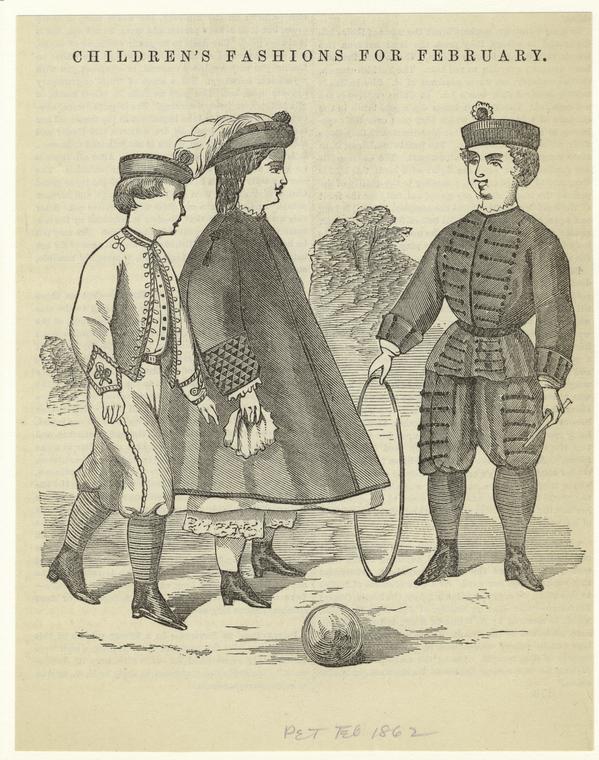

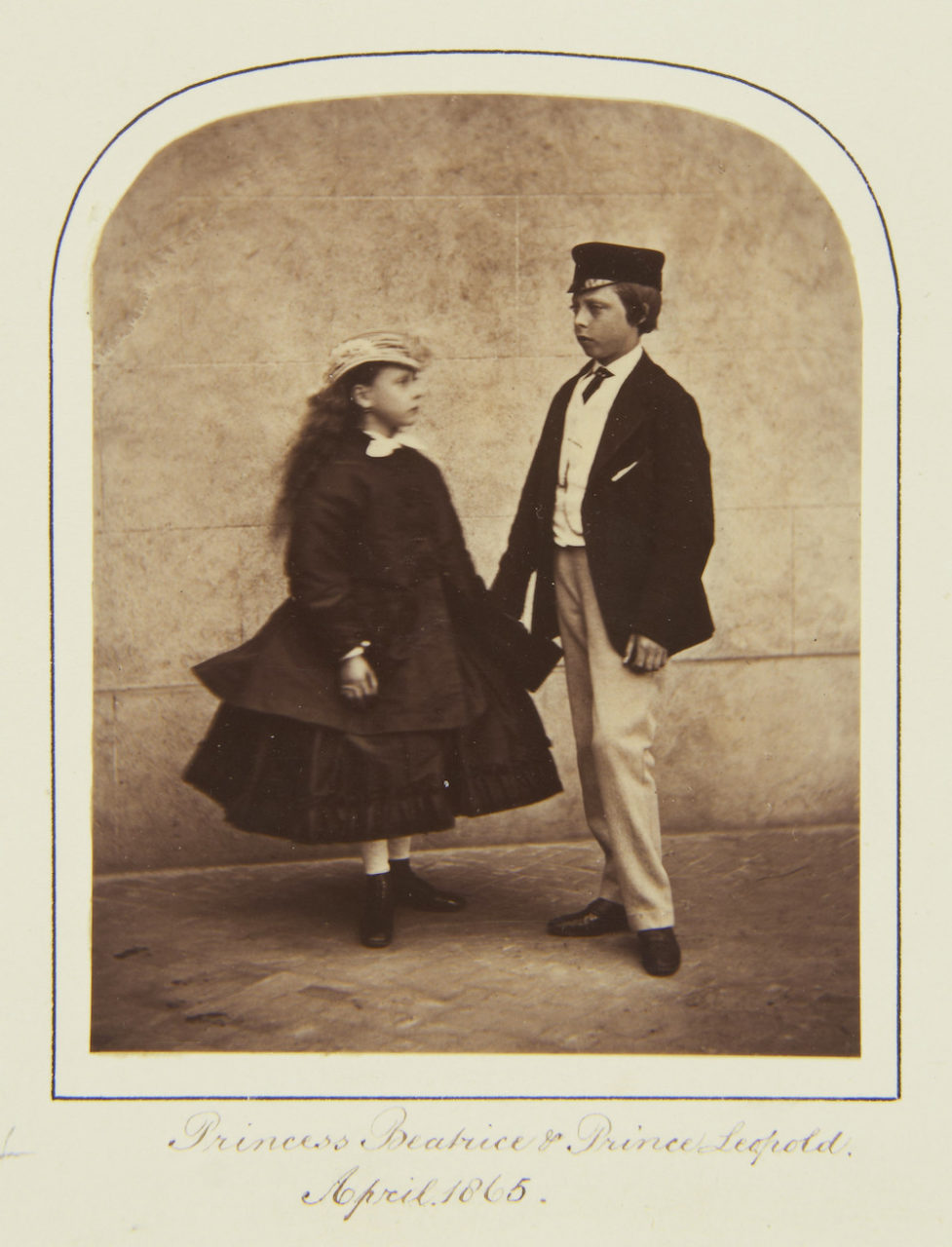

After breeching, small boys wore long trousers and a variety of jackets. Knickerbockers, trousers that buckled below the knee, had been introduced for young boys in the early 1860s (Shrimpton 46), and they were soon a common option as well. With both long trousers and knickerbockers, a small boy could wear a sack jacket, sometimes belted (Severa 211). Another option was a wide-cut Zouave jacket, much like their mother’s, short, buttoned at the neck, and featuring braided trim (Fig. 3) (Shrimpton 46). Underneath sack or Zouave jackets, the shirt sometimes buttoned onto the matching trousers (Fig. 4). The sailor suit, with its distinctive square collar and V-neck opening, was also a common choice for small boys (Tortora 374). Soft felt hats were worn, and there was a marked trend for the peaked “kepi” cap modeled after the military wear of soldiers in the Civil War, seen in the boy’s hand in Figure 4 (Shrimpton 46). After the age of ten, boys were usually dressed as miniature adults, in suits cut much like their father’s (Fig. 5), and by sixteen, were considered full grown men.

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (English). Boy's dress, 1865. Wool, cotton, mother-of-pearl buttons. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, AC1997.191.16. Gift of Helen Larson. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). Portrait of the Marquis and Marchioness of Miramon and their Children, 1865. Oil on canvas; (69.68 x 85.43 in). Paris: Musée d'Orsay, 144940. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Children's Fashions for February, February 1862. Print; (6 1/2 x 5 in). New York: New York Public Library, PC COSTU-186-Am. Source: New York Public Library

Fig. 4 - Photographer unknown (American). Young boy in uniform costume holding kepi, ca. 1862. Ambrotype photograph. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-41116. Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 5 - Jabez Hughes (British, 1819-1884). Princess Beatrice and Prince Leopold, April 1865. Carbon print; 9.2 x 7.4 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2901195. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (American). Girl's dress: Bodice and Skirt, ca. 1860. Silk taffeta, velvet ribbon, rhinestones. Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1950-60-8a,b. Gift of Bertha Lippincott Coles, 1950. Source: The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Young girls were dressed as miniature adults, and their dress reflected the silhouette worn by their mothers, simply shortened to reveal their pantalettes or drawers below (Figs. 3, 5). While children’s crinolines were rare, multiple stiffened petticoats were worn to give the same effect (Rose 83). Girls’ dresses could feature all the pleats and trims of adult fashions (Shrimpton 50), and young girls wore jewelry and styled their hair in curls as well (Olian iv). For small girls, under the age of ten, dresses often featured off-the-shoulder short sleeves (Fig. 6). Like their elders, the garibaldi and Zouave jacket was a popular choice (Fig. 7); La Mode Illustrée noted in December 1860 that the Zouave was “so widely adopted that there is no longer anything eccentric about it.” (Olian v). Paletots and capes were standard outerwear (Figs. 3, 5); frequently a dress and cape were made as a matching ensemble for young girls (Shrimpton 51). Dresses covered with a delicate pinafore became fashionable towards the end of the decade, echoing the layered skirts of adult fashions (Rose 82). By the age of sixteen, hemlines dropped to one or two inches above the floor. Young ladies drew their hair up into chignons, and full hoops were introduced (Tortora 372).

Fig. 7 - Photographer unknown. Little Girls, ca. 1863. Source: Pinterest

References:

- Coleman, Elizabeth Ann. The Opulent Era: Fashions of Worth, Doucet, and Pingat. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd., The Brooklyn Museum, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/469409564

- Cumming, Valerie ed., The Dictionary of Fashion History. New York: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1003643284

- Cunnington, C. Willett. English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Guide with 1,117 Ilustrations. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868281120

- “History of Fashion: 1840-1900.” The Victoria & Albert Musuem. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/history-of-fashion-1840-1900/

- “Issac Singer.” Brittanica Online. Last updated October 23, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Isaac-Singer

- Krick, Jessa. “Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895) and the House of Worth. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Last updated October 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wrth/hd_wrth.htm

- Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/966352776

- Mitchell, Rebecca N., ed. Fashioning the Victorians: A Critical Sourcebook. London: Bloomsbury, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1085349620

- Olian, JoAnne, ed. Children’s Fashions 1860-1912. New York: Dover Publications, 1994. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28963700

- Perrot, Philippe. Fashioning the Bourgeoisie: A History of Clothing in the Nineteenth Century. Translated by Richard Bienvenu. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/36749964

- Rose, Clare. Children’s Clothes: 1750-1985. London: BT Batsford, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/317672212

- Severa, Joan L. Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion 1840-1900. Kent, Ohio: Kent State UP, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/552147475

- Shrimpton, Jayne. Victorian Fashion. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/896980798

- Thieme, Otto C., Elizabeth A. Coleman, Michelle Oberly, and Patricia Cunningham. With Grace and Favor: Victorian & Edwardian Fashion in America. Cincinatti: Cincinatti Art Museum, 1993. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/260147672

- Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865480300

- Trubert-Tollu, Chantal, Françoise Tétart-Vittu, Jean-Marie Martin-Hattemberg, and Fabrice Olivieri. The House of Worth 1858-1954: The Birth of Haute Couture. London: Thames & Hudson, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1027406188

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1860-1869

Rulers:

- America

- President James Buchanan (1857-61)

- President Abraham Lincoln (1861-65)

- President Andrew Johnson (1865-69)

- President Ulysses S. Grant (1869-77)

- England: Queen Victoria (1837-1901)

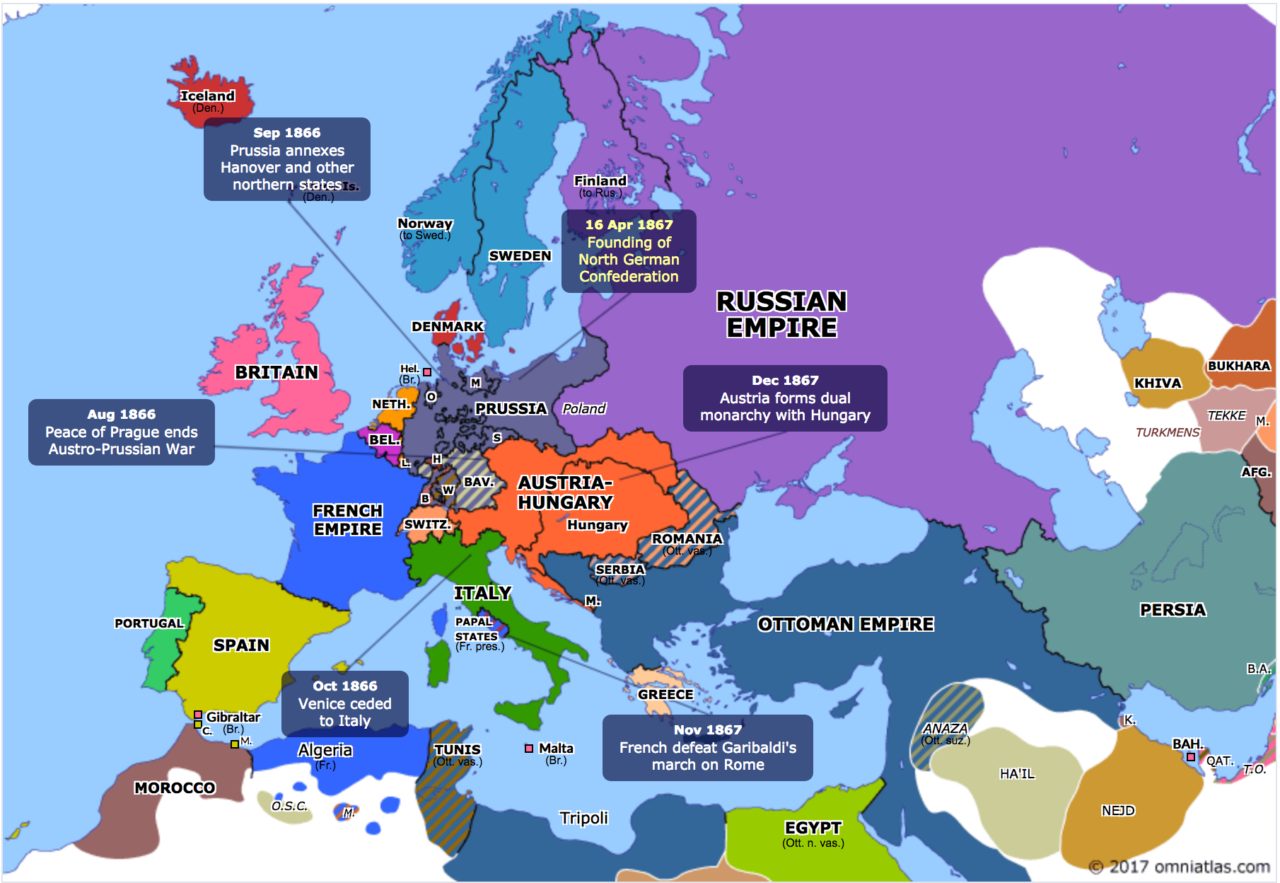

- France: Emperor Napoleon III (1852-70)

- Spain

- Queen Isabella II (1833-68)

- Regent Francisco Serrano y Domínguez (1868-71)

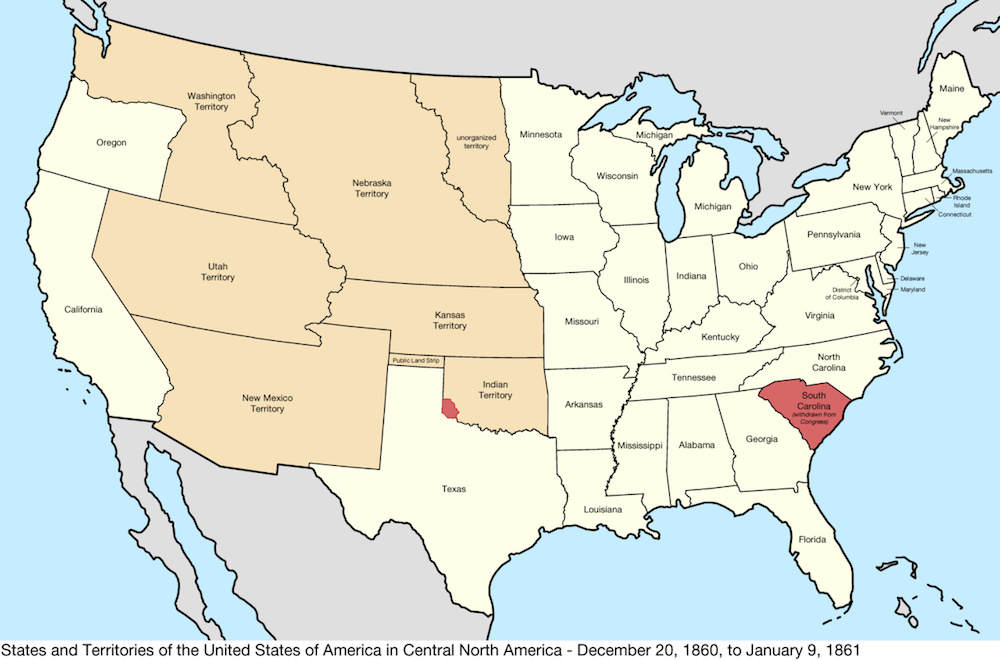

Events:

- 1860 – Snapshot photography steel developed

- 1861 – Italy unifies

- 1861-1865 – American Civil War

- 1863 – The Salon des refusés is held in Paris

- 1867 – Harper’s Bazar first published

- 1867 – Dominion of Canada created by the British North America Act

- 1869 – Suez Canal built

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library:

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine (London: 1852-79), 1860-64, 1867-69 (TT500 .E6)

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Womenswear Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Menswear Periodicals / Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 19th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.