To date, these fragments of dress are the only surviving testimonies of elite feminine garments in the Late Byzantine Empire. They offer a remarkable insight into what might have been the fashion habit in Mystras (Greece) and reflect the prestigious and multicultural civilization of Byzantium during the 15th century.

About the Look

Excavated from a tomb in the church Hagia Sophia of Mystras, the corpse and the dress of a young noblewoman were found in 1955 (Fig. 1). In the late 1990s a collaboration between the Museum of Art and History (MAH) of Geneva and the Hellenic Ministry of Culture allowed for the restoration and analysis of these remains. The conclusions of their research were published in 2000 and edited by Marielle Martiniani-Reber in Parure d’une princesse Byzantine. Tissus archéologiques de Sainte-Sophie de Mistra.

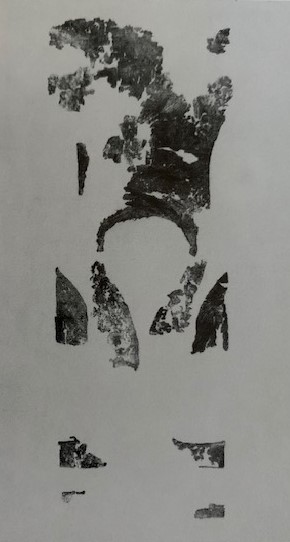

Fig. 1 - Maker unknown (Byzantine). Hagia Sophia, tomb n°5, Fragments of the damask dress,, 15th century. Silk damask. Mystras, Greece: Archaeological Museum of Mystras. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 2 - Maker unknown (Byzantine). Hagia Sophia, tomb n°5, Fragments of the damask dress,, 15th century. Silk damask. Mystras, Greece: Archaeological Museum of Mystras. Source: Wikipedia

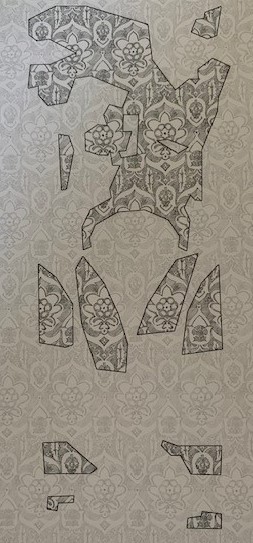

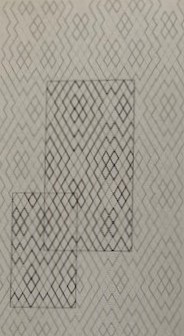

Fig. 3 - Maker unknown (Byzantine). Drawing of patterns on the fragments of the damask dress,, 15th century. Silk damask. Mystras, Greece: Archaeological Museum of Mystras. Source: Wikipedia

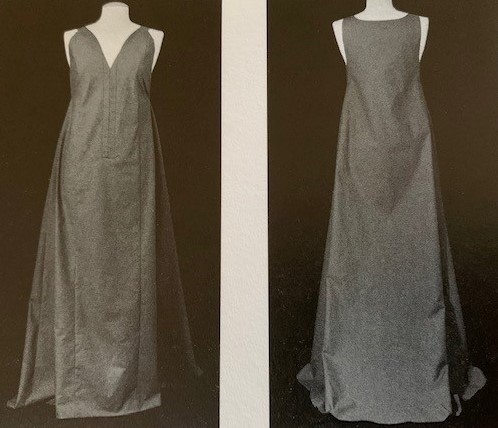

Among the extant pieces, fragments of a dress were identified (Figs. 2-3): a large part of the back and some belonging to the chest. The analysis of this fabric allowed the archeologists to date the corpse from the first half of the 15th century (Martiniani-Reber 87). The reconstruction shows a long and sleeveless dress, adjusted at the bustline, which flares considerably from under the breast (Figs. 4-5). The back is tailored from one sole piece of fabric. A princess line made of an association of bust and waist darts creates this curve effect at the breast (Fiette 37-38). According to Fiette, this line could be similar to the dress worn by the Madonna in the famous Jean Fouquet painting (Fig. 6). There are no remains of any fastening system but there could have been buttons or ties at the middle front (Kalamara 148). The dress is made of silk damask adorned with quite a large intricate floral pattern (Fig. 3). No residue of dyes survived the burial process. The red look of the silk could probably be the consequence of its long stay within the tomb (Walton Rogers, 85).

Fig. 4 - Maker unknown. Reconstruction of the damask dress and the pattern behind, 2008. Mystras, Greece: Archaelogical Museum of Mystras. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 5 - Maker unknown. Reconstruction of the damask dress and the pattern behind, 2008. Mystras, Greece: Archaelogical Museum of Mystras. Source: Wikipedia

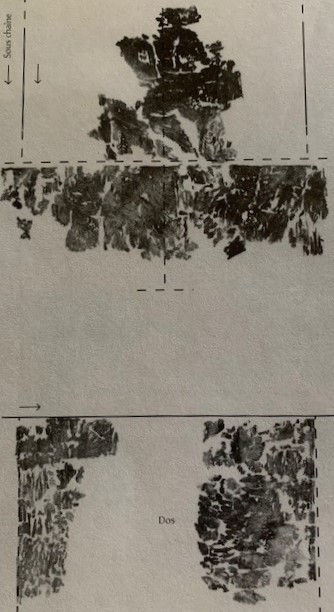

Four pieces of plain and presumably undyed taffeta with a woven pattern were found on the corpse (Figs. 7-8). They originally formed a simple T-shape tunic of undetermined length with cylindrical sleeves, that was worn under the dress described above (Kalamara 149). Two slightly different woven and tone on tone patterns can be identified, however the largest and most complex one is used to adorn the part of the shirt that can be seen when worn under the silk damask dress: the sleeves, the shoulders, and the bust (Kalamara 150). Its patterns combined juxtaposed and interlocked lozenges and X shapes (Fig. 9).

Fig. 6 - Jean Fouquet (French, 1420-1477/1481). Madonna Surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubim, ca. 1450. Antwerp: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, 132. Source: KMSKA

Fig. 7 - Maker unknown (Byzantine). Fragments of the taffeta tunic, 15th century. Silk taffeta; 70 x 59 cm (back), 38 x 25 and 39 x 22 cm (front). Mystras, Greece: Mystras Museum, inv. N° 1745. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 8 - Maker unknown (Byzantine). Fragments of the taffeta tunic, 15th century. Silk taffeta; 70 x 59 cm (back), 38 x 25 and 39 x 22 cm (front). Mystras, Greece: Mystras Museum, inv. N° 1745. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 9 - Maker unknown (Byzantine). Drawing of pattern on fragments of the taffeta tunic, 15th century. Silk taffeta; 70 x 59 cm (back), 38 x 25 and 39 x 22 cm (front). Mystras, Greece: Mystras Museum, inv. N° 1745. Source: Wikipedia

About the context

Mystras was a political, trading, and cultural center that thrived over the last centuries of the Byzantine Empire. It was founded in 1249 during the Latin occupation of Byzantium by a Frank Crusader, Guillaume II Villehardouin. From 1262, after the city was reconquered by the Byzantines, it became a major urban center and then the capital of the despotate of the Morea located in the current Peloponnese region (Greece). Its growing development is due to the city’s close links with Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine empire, and its geographical location. Mystras was ideally situated on the main trade roads with the Western kingdoms meanwhile isolated from the Eastern conflicts with the Turks (Bacourou 19).

The Morea was governed by despots, close relatives of the Byzantine emperors. The empire, severely struck by the Turk conquests and the dominance of the Western merchants in the sea, was in a weak position in the Late Medieval world. On the contrary, Mystras thrived in the last two centuries of its existence. The rulers succeeded in maintaining peace with the Western Latin communities in and outside their borders, as well as close contact with Constantinople (Bacourou 20). The brilliant court of the despots attracted politicians and scholars such as the philosopher Bessarion that promoted Mystras as a major cultural center (Alcouffe, Avisseau-Broustet, Baratte 424).

In the despotate of the Morea, Mystras had become a growing trading center under the Palaiologan rulers. Silk and other textile raw materials destined for the local and western markets were produced in the region. However, the manufacturers were hit by the economic recession and the lack of technical expertise (Mexia 65-66). Thus, the elite of the Morea imported their luxury goods, such as clothes, from Venetian and Florentine merchants established in trading posts in the Morea (Mexia 65-66). Scholars in Mystras lamented that the Byzantines were no longer able to produce garments, like the philosopher Plethon who stated:

It is a great evil for a society which produces wool, linen, silk, cotton, to be unable to fashion these into garments and instead to wear the clothes made in the lands beyond the Ionian Sea from wool produced in the Atlantic (Laiou-Thomadakis 187).

Some elements of the dress found on the remains of the young woman buried in the church of Hagia Sophia in Mystras provide evidence that the Byzantine elite women in the 15th century wore garments with a mix of Byzantine tradition and Western fashions.

Fig. 10 - Rogier van der Weyden (Netherlandish, died 1464). Triptych of the Braque family (right panel), 15th Century. Oil painting on wood panel; 41x136 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre, inv. N° RF2063. Photo©RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Tony Querrec. Source: L’Agence Photo RMN Grand Palais

Concerning the fabrics used for the tunic and dress, Marielle Martiniani-Reber noticed their lightness and fineness compared to the Byzantine cloths preserved in the treasures of Western cathedrals. According to her, the taffeta used for the tunic is like numerous Spanish textile fragments and the patterns of the damask of the dress show similarities with 15th and 16th century Italian velvet fabrics. These fabrics attest to a change in the fashion of the feminine aristocrats of Late Byzantium. Such change is also documented by many representations of elite women in wall paintings of Mystras and Constantinople churches.

The simple T-shaped tunic was an inheritance of the Late Antique tradition. However, the way the tunic and the dress are worn, confronted with a mural painting of a feminine donor in Mystras, testifies that for the first time in Byzantium, the inner layers of garments were revealed at the bust and the sleeves similar to the Western fashions of this period (Fig. 10). However, for the sleeves, this concept had already been initiated in the 13th century in Mani – located in the same region of Peloponnese as Mystras – which was at this time ruled by the Frank conquerors (Tournier 101-103).

The damask dress with its adjusted upper body that becomes large in the bottom is similar to 15th-century Western dresses. This shape was favored by the young women in the West (Florent Véniel 192). Some seams along the armholes, invite us to think that a braided finish was sewn there, like the one that remains at the neckline (Kalamara 106). Pari Kalamara demonstrates that the absence of sleeves is probably due to the Western fashion influence in the Byzantine Empire or its former territories like Cyprus. It was also common that Western women from the elite wore non-permanent sleeves, sometimes made in a different and luxurious material attached to the dress with pins (Fig. 10).

However, due to the extensive presence of foreigners in Mystras as well as the long-standing tradition of Palaiologan rulers to marry Western princesses, we cannot exclude that the young woman buried in Hagia Sophia was of Western origin or born from an intermarriage between a Byzantine and a Westerner. Mystras was a cosmopolite city, like Constantinople, where the historian Nikephoros Gregoras described, as early as the 14th century, the emperor‘s Andronikos III’s court:

Thus these [headdresses of the courtiers] were varies in form and strange and according to the whim of each. For some wore Latin, some similar to those of the Bulgarians and Serbs, others coming from Syria and Phoenicia, and others yet other [types], as each person saw fit. Thay had the same habit with regard to their garments” (Talbot 19).

References:

- Alcouffe, Daniel, Avisseau-Broustet, Mathilde, Baratte, François. Byzance: l’art byzantin dans les collections publiques françaises. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1992. Exhibition catalogue. https://www.worldcat.org/title/90661020

- Bacourou, Aimilia. “Mistra : le contexte historique.” In Parure d’une princesse byzantine : tissus archeologiques de Sainte-Sophie de Mistra, Marielle Martiniani-Reber (ed.). Geneva: Musées d’art et d’histoire de Genève, 2000, 19‑26. https://www.worldcat.org/title/878549795

- Fiette, Alexandre. “Ensemble archéologique provenant de Mistra.” In Parure d’une princesse byzantine : tissus archeologiques de Sainte-Sophie de Mistra, Marielle Martiniani-Reber (ed.). Geneva: Musées d’art et d’histoire de Genève, 2000, 35‑51. https://www.worldcat.org/title/878549795

- Kalamara, Pari. “Le costume à Mistra à la fin de la période Paléologue : données provenant de la fouille des tombes de Sainte Sophie.” In Parure d’une princesse byzantine : tissus archeologiques de Sainte-Sophie de Mistra, Marielle Martiniani-Reber (ed.). Geneva: Musées d’art et d’histoire de Genève, 2000, 105-118. https://www.worldcat.org/title/878549795

- Kalamara, Pari. “The dress worn by the inhabitants of Mystras.” In The City of Mystras. Byzantine Hours: Works and Days in Byzantium, Hellenic Ministry of Culture (ed.). Athens: Kapon Editions, 2001, 143‑51. Exhibition catalogue. https://www.worldcat.org/title/48369297

- Laiou-Thomadakis, Angeliki E. “The Byzantine Economy in the Mediterranean Trade System; Thirteenth-Fifteenth Centuries.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 34/35 (1980): 177‑222. https://www.worldcat.org/title/5547907833\

- Martiniani-Reber, Marielle, Parure d’une princesse byzantine : tissus archeologiques de Sainte Sophie de Mistra. Geneva: Musées d’art et d’histoire de Genève, 2000. https://www.worldcat.org/title/878549795

- Mexia, Angeliki. “Crafts and Industries.” In The City of Mystras. Byzantine Hours: Works and Days in Byzantium, Hellenic Ministry of Culture (ed.). Athens: Kapon Editions, 2001, 66‑67. Exhibition catalogue. https://www.worldcat.org/title/48369297

- Talbot, Alice-Mary. “Revival and Decline: Voices from the Byzantine Capital.” In Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261-1557), Helen C. Evans (ed.). New York: Yale University Press, 2004, 17‑25. Exhibition catalogue. https://www.worldcat.org/title/54082338

- Tournier, Sonia. Tenues féminines aristocratiques entre Byzance et l’Occident. Expressions et mises en œuvre en Grèce au Moyen Âge central et tardif. (Master’s thesis). 2023.

- Véniel, Florent. Le costume médiéval de 1320 à 1480 : la coquetterie par la mode vestimentaire. Saint-Martin-des-Entrées: Éditions Heimdal, 2021. https://www.worldcat.org/title/1291179492

- Walton Rogers, Penelope. “Analysis for dye of a 15th-century silk dress from St Sofia Mistra.” In Parure d’une princesse byzantine : tissus archeologiques de Sainte-Sophie de Mistra, Marielle Martiniani-Reber (ed.). Geneva: Musées d’art et d’histoire de Genève, 2000, 85. https://www.worldcat.org/title/878549795