OVERVIEW

The high-waisted neoclassical silhouette continued to define womenswear of the 1810s, as fashion remained inspired by classical antiquity. However, the purity of the line was increasingly broken by trim, colors, and a new angularity as tubular skirts were gradually replaced by triangular ones by the end of the decade. Menswear was led by British tailors, as a perfect fit was paramount. World events such as the Napoleonic Wars played a large role in shaping fashion of the period.

Womenswear

“The fashions of every nation and of every era are open to [a woman’s] choice. One day she may appear as the Egyptian Cleopatra, then a Grecian Helen; next morning the Roman Cornelia; or, if these styles be too august for her taste, there are Sylphs, Goddesses, Nymphs of every region, in earth or air, ready to lend her their wardrobe. In short, no land or age is permitted to withhold its costume from the adoption of a…woman of fashion.” (Davidson 38)

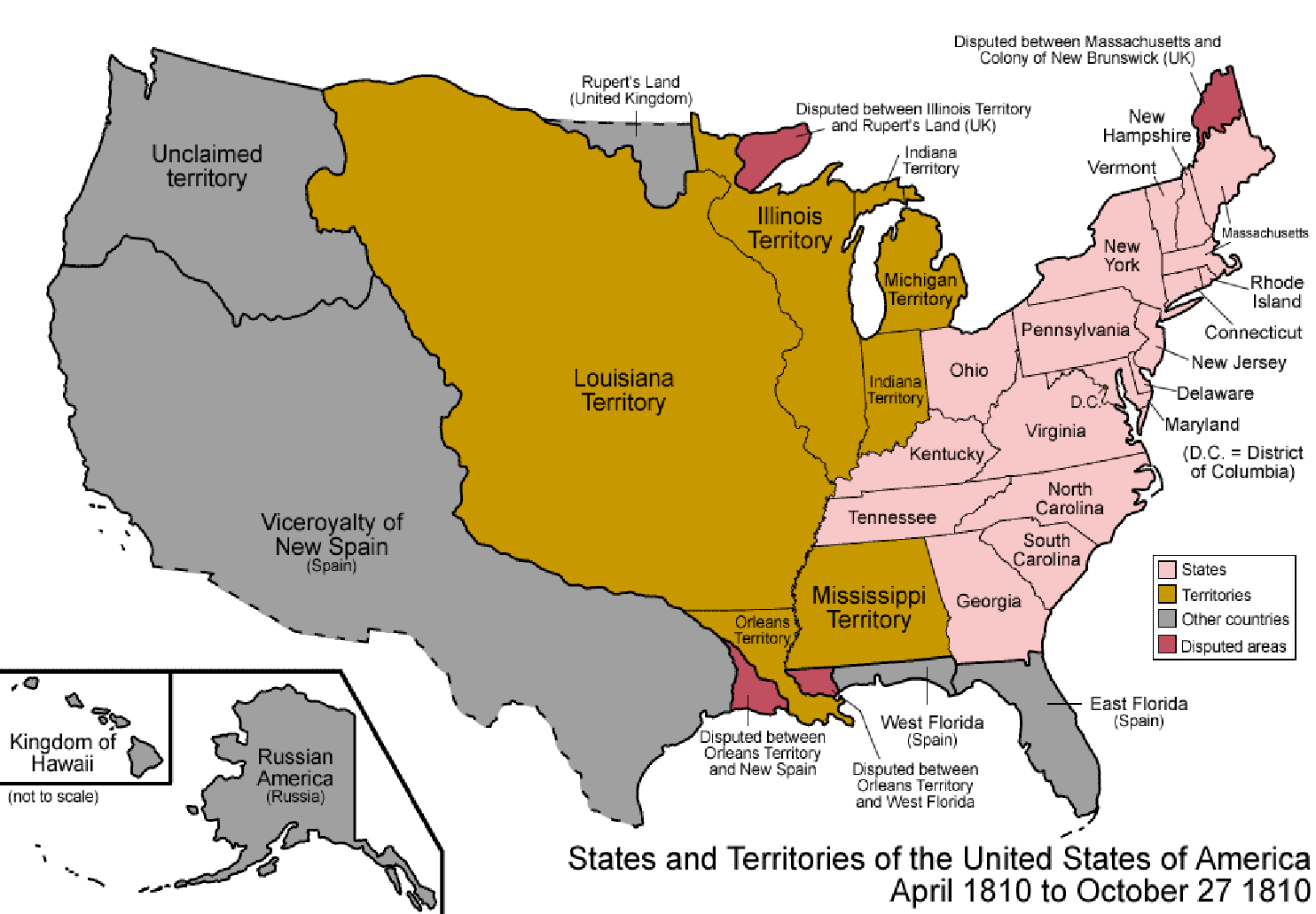

The Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) played an enormous role in the development of fashion, spreading trends across Europe and inspiring a martial appearance in both men’s and women’s clothing. Notably, during the first years of the 1810s, Britain and France were cut off from one another during the Continental blockade. While there is some debate as to how much fashion information crisscrossed the battle lines, there is no doubt that the two countries’ fashions diverged (Davidson 235-245). Most notably, when left to their own devices, British women began to lower the waistline. In 1814, when the British could once again cross the Channel following the Peace of Paris, they were ridiculed by the French. British women quickly adopted the French styles, raising the waistline to its highest point yet (Tortora 313; Byrde 31, 34; Laver 156). Indeed, Paris was the leading fashion capital, and during the war, Parisians were present at every conflict, helping to spread French Empire style (le Bourhis 109). The United States continued to receive fashion news from both Britain and France during the war, but fashion-conscious American women desired French fashion most of all, as did their European counterparts (Tortora 313; le Bourhis 102, 237).

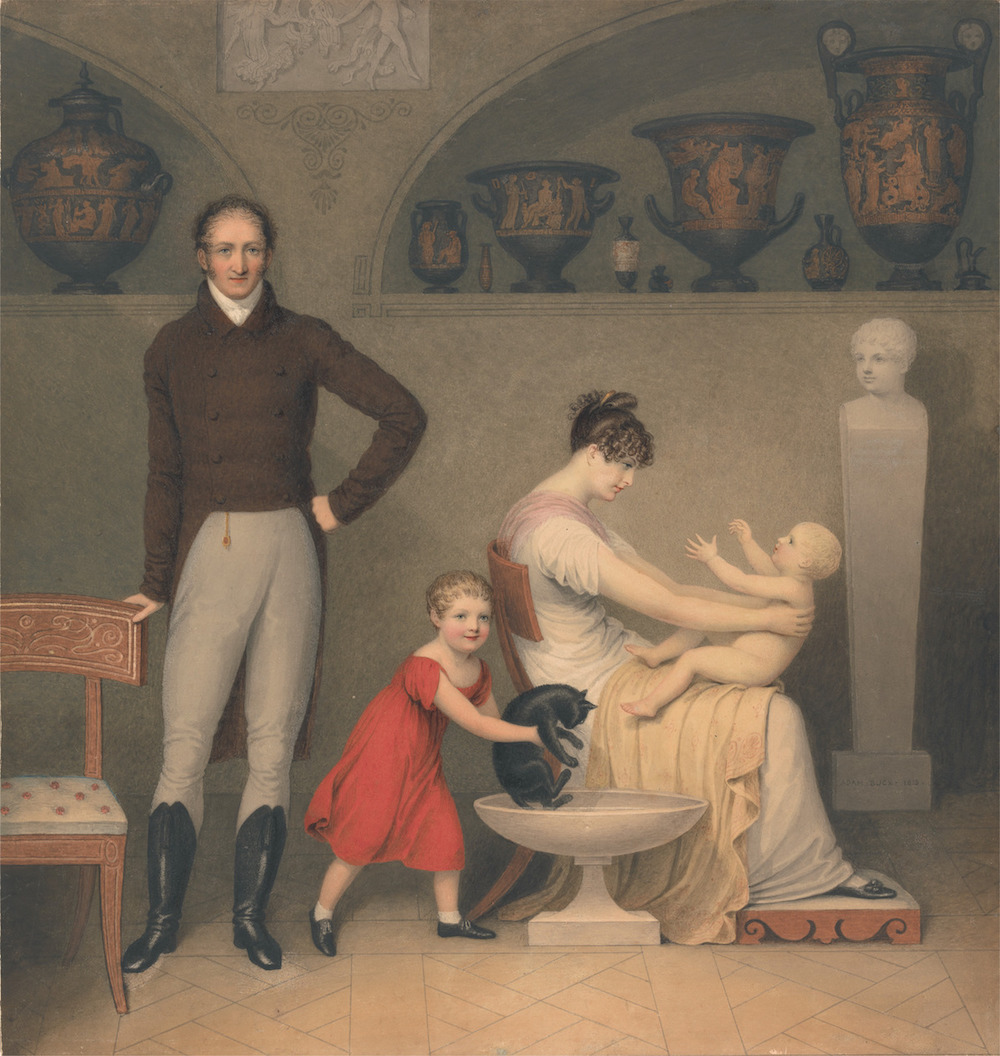

Fig. 1 - Adam Buck (British, 1759-1833). The Artist and His Family, 1813. Watercolor, ink and paper; 44.6 x 42.4 cm. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Center for British Art, B1977.14.6109. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: Yale Center for British Art

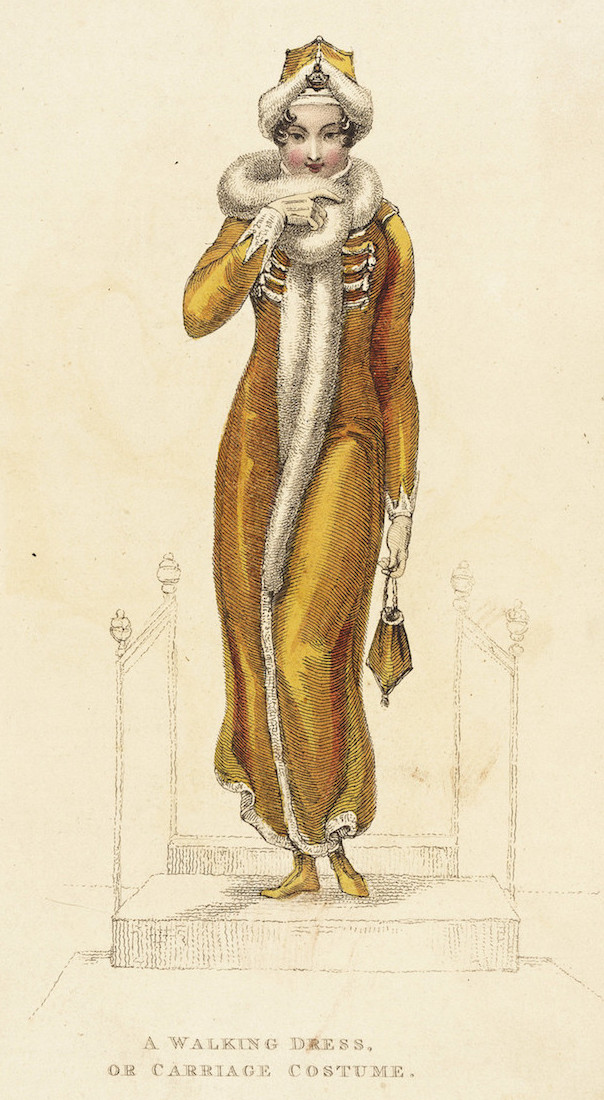

Fig. 2 - Rudolph Ackermann (English, 1764-1834). Fashion Plate: "Walking dress or Carriage Costume" for "The Repository of Arts", February 1, 1811. Hand-colored engraving on paper; (9 5/8 x 5 11/16 in). Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.83.161.270. Gift of Charles LeMaire. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Fashion Plate: "London Dresses for November" for "Ladies' Museum", November 1810. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Public Library, rbc0318. Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Along with the bustle pad, women wore stays and corsets, especially to support the bust. During this period, stays more usually referred to stiff, heavily boned structures like those of the eighteenth century, while corsets were a lighter garment with minimal or no boning. However, as corsets supplanted stays, the words were increasingly used interchangeably (Davidson 64). Both long and short stays were worn. Long stays, extending past the hip were ideal for creating the willowy, slender silhouette (Foster 31). A variation on the corset appeared around 1810, nicknamed the “Divorce Corset” as it featured a stiff panel that separated the breasts, ideal for the wide, square necklines; these were often rather short-waisted as the main objective was to shape the breasts. A petticoat was also worn which followed the shape of the skirt (C.W. Cunnington 72-73).

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (Probably English). Evening dress, 1818-1822. Silk. Cincinnati, Ohio: Cincinnati Art Museum, 1986.1017. Gift of Webb and Stacey Hill, by exchange. Source: Cincinnati Art Museum

Fig. 5 - Rolinda Sharples (English, 1793-1838). The Cloakroom, Clifton Assembly Rooms, 1817. Oil on canvas. Bristol, U.K.: Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, BAG13607. Source: British Library

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (Probably French, worn by an American). Dress, 1815-1820. Silk. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 49.874. Gift of Emily Welles Robbins (Mrs. Harry Pelham Robbins) and the Hon. Sumner Welles, in memory of Georgiana Welles Sargent. Source: Museum of Fine Arts

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. Fashion Plate: Evening Dresses, 1818. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

Fig. 8 - Sir Martin Archer Shee (Irish, 1769-1850). Lady Jane Monro, 1819. Oil on canvas; (30 1/4 x 25 3/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 3124. Purchased, 1942. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (English or French). Dress, ca. 1818. Cotton muslin. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.79-1972. Given by Miss Joan Gibbon. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown. Fashion Plate: Autumnal Walking dress, 1815. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (English). Redingote, ca. 1810. Wool flannel. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC5646 87-27-1. Source: Kyoto Costume Institute

Trim and decoration were the fashionable elements that most disrupted the Classical line during this period. As early as 1812, skirts began to feature horizontal tucks at the hem (C.W. Cunnington 34). By 1815, this hem decoration became more elaborate as flounces of lace, often featuring scalloped or vandyked edges, were applied as well. At the advent of the 1820s, skirts were richly festooned with not only tucks and flounces, but satin rouleaux (stuffed tubes of fabric), puffs, and embroidery in a wide variety of designs (Fig. 7). By 1815, the emphasis on trims spread to the bodice and sleeves; sleeve caps known as mancherons, were common, and panes of fabric at the shoulder revealing puffs underneath became very fashionable by the end of the decade (Fig. 8) (Byrde 35-36; Foster 32; Davidson 38). The increasing trim reflected a move away from Neoclassical influence to a Romantic one. In an arguably “Gothic” style, many elements of fashion were drawn from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Panes and puffs imitating slashing (Fig. 8), ruff collars (Figs. 8, 10), “vandycked” edges, extra-long sleeves that came over the hand, and the very modish “Marie” sleeve, which was a long sleeve banded down at intervals to form a series of puffs (Fig. 9), were all examples of such Romantic historicism (Johnston 46; Davidson 37-38; C. W. Cunnington 29; le Bourhis 100).

Outerwear was rich and varied during the 1810s. The pelisse or redingote, both types of long coats, or the spencer, a cropped jacket (Fig. 10), were the most common (C.W. Cunnington 35-38; le Bourhis 98). By 1817, the pelisse developed into the pelisse-robe, a coat-dress that could be worn by itself (Byrde 27). These garments often displayed the influence of the wars, with a widespread use of military-inspired trim. The uniforms of the Napoleonic Wars were some of the most elaborate and dashing in military history, providing excellent material for fashion (Johnston 18-20). Braid, tassels, frogging, and cords festooned female outerwear especially. The hussar cavalry uniforms served as a particular inspiration; observe figure 2 of the Menswear section. Fashion frequently borrowed their horizontal braid and Brandenburg buttons (Fig. 11) (Fukai 148-151; Byrde 30; Davidson 233). Finally, Kashmiri shawls imported from India, highly-prized and prohibitively expensive for most women, were a much-desired accessory (Fig. 6). Note the shawls worn by Empress Joséphine in the Fashion Icon section below and the woman in figure 4 of the Children’s Wear section. During the first decades of the nineteenth century, there was an expansion and development in the imitation market, most notably in Paisley, Scotland. The city’s name became synonymous with the Indian pine or boteh/buta motif that decorated the shawls (Laver 155; Davidson 273; Ashelford 179).

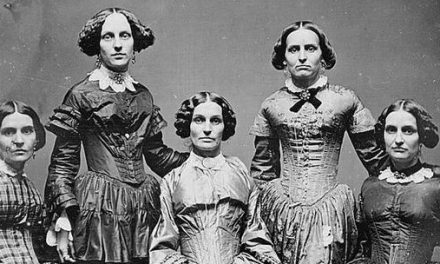

Textiles became more diverse during the 1810s; firmer cottons and silks supplanted the draping fine muslins of the previous years. Additionally, while white remained a color very much in vogue throughout the decade, it gave way to increasingly brighter colors and patterns such as stripes (Byrde 36; Foster 36). Lightweight, transparent nets became extremely popular after the bobbin-net machine was patented by John Heathcoat in 1808, which made the material more affordable (Johnston 146; le Bourhis 100). This net could be embroidered and further decorated, and evening dresses were frequently made entirely of transparent net worn over a silk satin slip (Fig. 12). Lace, particularly the silk “blonde” variety, was a desirable material as well (Davidson 220-223). These lightweight materials softened the stiffer silks and cottons, lending a Romantic quality to a woman’s appearance (Foster 39). Overall, though, textiles lost the sense of fluidity that defined gowns of the previous two decades; by the end of the 1810s, “a soft, curving femininity was established…one featuring stiffer surfaces with increased decoration” (Davidson 26) (Fig. 13).

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (English). Evening dress, ca. 1810. Machine-made silk net, embroidered with chenille thread and silk ribbon. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.194-1958. Given by Mrs George Atkinson and Mrs M. F. Davey. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 13 - Designer unknown (British). Dress, 1817-1820. Silk, cotton, metal. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.110 to B-1969. Given by Mrs A. Wallinger. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

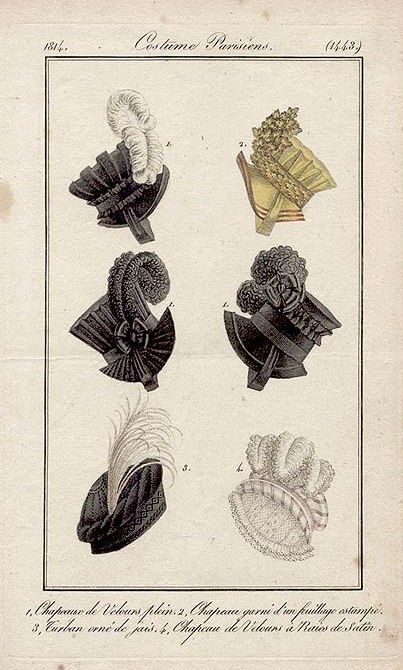

Fig. 14 - Artist unknown (French). Fashion Plate: Costume Parisien, 1814. Source: Pinterest

FAshion icon: Empress Joséphine bonaparte (1763-1814)

Marie-Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie, better known as Empress Joséphine Bonaparte, was the undisputed leader of fashion during the early nineteenth century (Fig. 1). Born to a Creole family in Martinique, she married Napoleon Bonaparte in 1796, and became Empress of the French in 1804, when Napoleon declared himself emperor. In that role, Joséphine rocketed to the forefront of fashion. Biographer Andrea Stuart wrote:

“She was the wife of the world’s most powerful man, and the most visible female figure of her era. Her every action and nuance of appearance were followed eagerly by newspapers and journals in France and abroad. She was the high priestess of style, and fashion-conscious women the world over idolized her. They pored over fashion journals like le Journal des Dames et de la Mode…in order to see what Josephine was wearing, and attempted to copy her style. Joséphine reinforced Paris’s position as fashion capital of the world, which in turn boosted French industry.” (ch. 16)

Joséphine was well-suited to the fashion of the era, adoring fine muslins and luxurious Kashmiri shawls, two pillars of womenswear.

Fig. 1 - Firmin Massot (Swiss, 1766-1849). Portrait of Joséphine de Beauharnais, 1812. Oil on canvas; 74 x 66 cm. Saint Petersburg: State Hermitage Museum, ГЭ-4928. Entered the Hermitage in 1922; formerly in the collection of Grand Duke Nikolai Mikhailovich. Source: Wikimedia

She played a major role in establishing the antique-inspired tunic with the era-defining high waistline (le Bourhis 95). Indeed, Indian shawls, the most coveted item of the time, were her signature piece, and she was considered the most elegant shawl-wearer in France. Joséphine negotiated her love of foreign fabrics with her husband’s desire to stimulate French industry. Napoleon restricted the importation of British muslin and Indian cashmere, but Joséphine continually found a way to incorporate them into her wardrobe (Jensen; Davidson 272). Importantly, though, she was also the face of the reinvigoration of the French fashion industry, which had been decimated following the French Revolution (Fukai 125). She had an insatiable appetite for new clothes, and amassed a shockingly large wardrobe. An 1809 inventory shows how she must have single-handedly boosted French manufacturing, as it included 49 court dresses, 666 winter dresses, 230 summer dresses, 60 cashmere shawls, and 1,132 pairs of gloves (Jensen; Tortora 311). Joséphine was also a passionate admirer of the French le style troubadour, a movement in art, literature, and fashion that borrowed elements from the Medieval past (Mackrell 71-73). Significantly, through her careful sartorial choices that often blended stalwarts of old France such as Lyonnaise silks with elements borrowed from across the Empire from the Middle East to the Caribbean, Joséphine exercised political power. She lent legitimacy to Napoleon’s rule and served as unifying symbol for the whole Empire (Jensen).

Although Joséphine died in 1814, she deserves her mention here, as no other woman exercised as much fashionable influence during the first two decades of the nineteenth century. Even after her death, fashions that she played a significant role in establishing remained in vogue. Other fashionable women of the 1810s, such as American First Lady, Dolley Madison, were followers of the French mode led by Joséphine (le Bourhis 230-237). Biographer Stuart summarized it well:

“As one of history’s great style icons, Joséphine’s influence on the way an entire generation wanted to look, dress and behave cannot be overstated.” (ch. 16)

Menswear

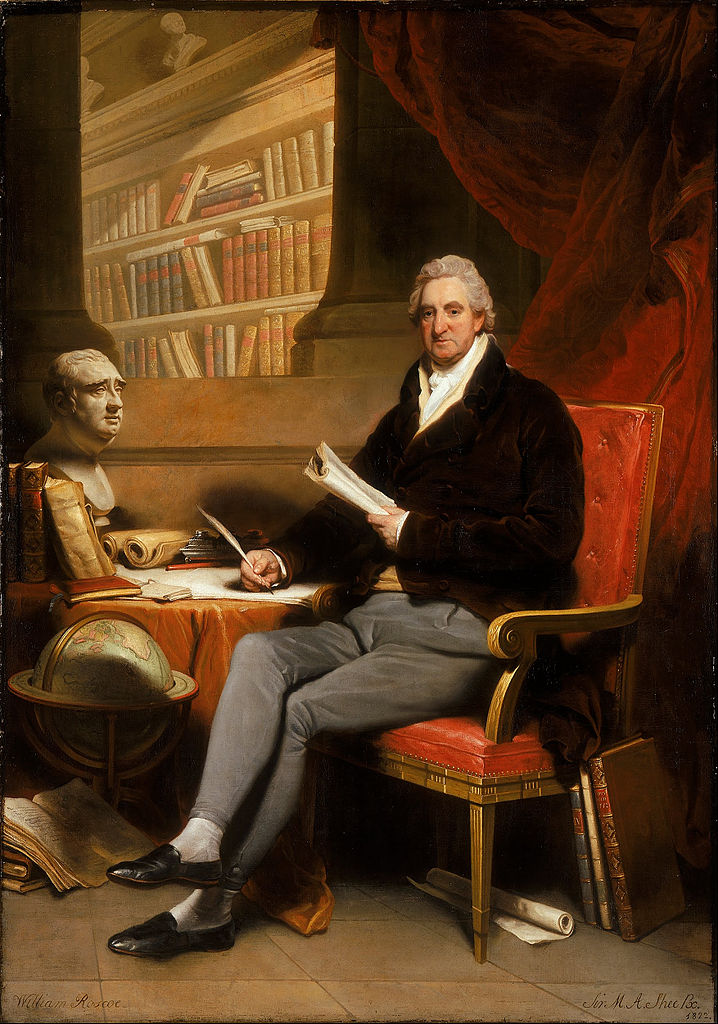

Menswear of the 1810s, like womenswear, was a continuation of trends set during the previous decade. However, there were important developments, and the silhouette changed subtly after 1811, as the waist dropped and padding was added to the shoulder (le Bourhis 112). An expert fit was of paramount importance, and Britain, with its superior tailors, continued to lead male fashion (Laver 158). Fine woolen cloth could be stretched and molded to fit the body, and it dominated the male wardrobe (Fig. 1); crepe or silk jersey pantaloons clung to muscled legs (Davidson 185, 232). Legendary British dandy, George Bryan “Beau” Brummell, set the example for the whole of Western fashion with his refined, perfectly tailored clothing, worn with a restrained air (Byrde 94-95; Ashelford 185-186). Color and adornment remained in retreat from men’s wardrobes, a trend that had begun in the previous decade, as menswear became understated and democratic. As in womenswear, the Napoleonic Wars exercised a marked influence in men’s fashion as men in uniform dominated public life (Fig. 2) (le Bourhis 112, 117).

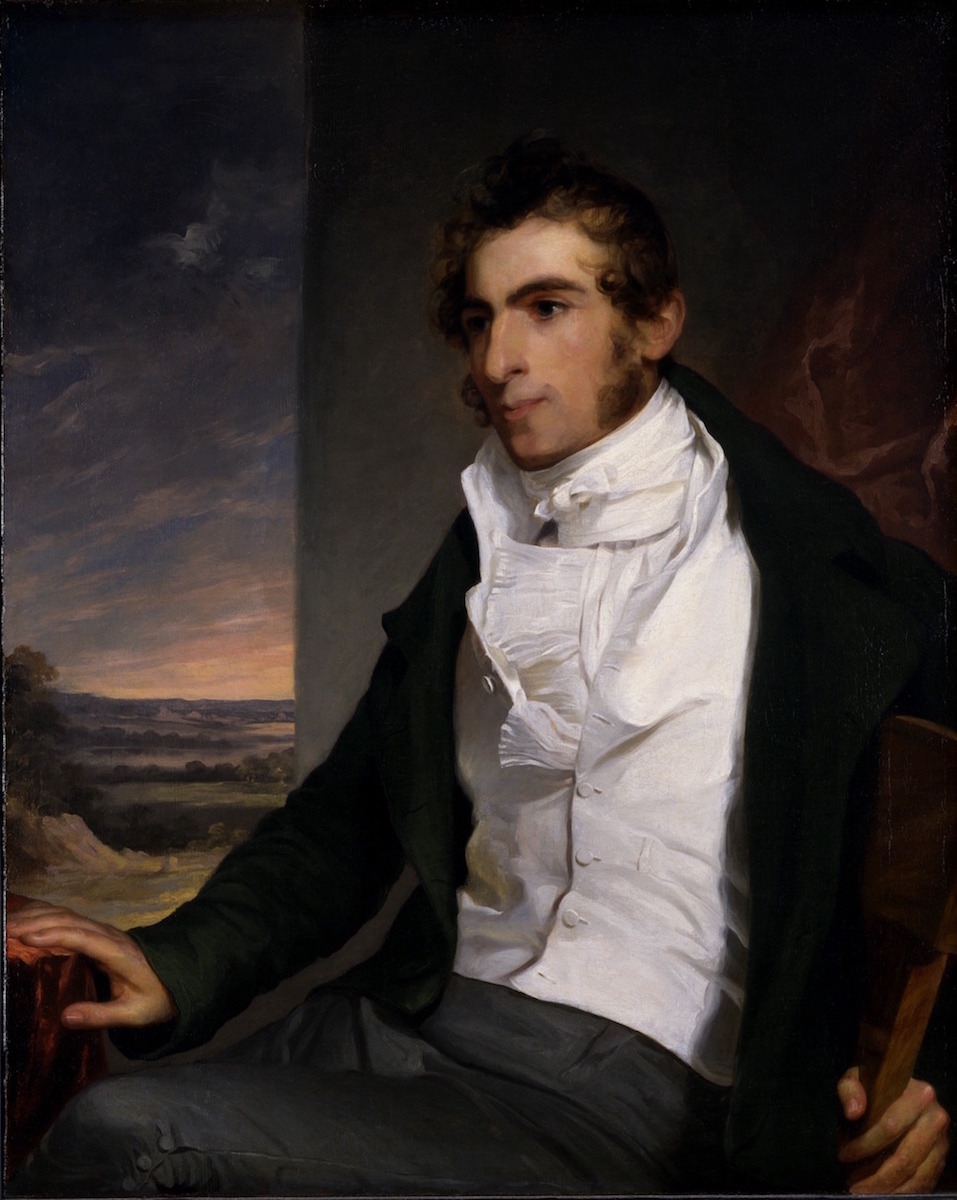

The three elements of a man’s suit were a coat, waistcoat, and breeches or pantaloons; it was rare for all three elements to be of the same color (Tortora 319). There were two main types of coats, both versions of the tailcoat: the dress coat (Fig. 3) and riding coat. The dress coat was cut in at the waist, either straight across or in an inverted U-shape. The riding coat, a less formal choice, sloped gently from the waist back to the tails (Byrde 91). Towards the end of the 1810s, fashion required a more nipped waistline and a smoother fit, so darts were added to eliminate the unsightly crease at the waist (Waugh 113). Both coats featured turn-down collars that were quite high at the back, and sloped down into lapels with sharp “M” or “V” notches (Laver 160; Johnston 138). Waistcoats were cut straight across the waist, single- or double-breasted, and featured tall stand collars (Davidson 28).

Both breeches and pantaloons were worn during the 1810s. Breeches extended to the knee where they were fastened with buttons and a buckle or tie (Fig. 1); pantaloons, which had originated in the 1790s, were very tightly-fitted and longer, extending to the calf or ankle where they fastened with ties or buttons (Fig. 4)(Byrde 93; Johnston 14). Either could be worn during the day, but breeches were the proper evening attire with white stockings and evening pumps (Fig. 5). For daywear, both were frequently worn with tall boots, a favorite fashion of early nineteenth century menswear (le Bourhis 112). It was particularly in vogue to wear pantaloons tucked into “hessian” boots, defined by heart-shaped tops and tassels (Laver 160). Named for the Hessian mercenary soldiers from Germany, these boots and clinging pantaloons, which displayed a man’s leg muscles to great effect, lent a martial glamour to civilian dress (Ashelford 186; Johnston 14). The man in figure 1 of the Womenswear section sports pantaloons and hessians.

Fig. 1 - William Owen (British, 1769-1825). Portrait of a Man, ca. 1815. Oil on canvas; (83 1/2 x 55 in). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Center for British Art, B1973.1.44. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: Yale Center for British Art

Fig. 2 - Sir Thomas Lawrence (English, 1769-1830). Charles William Vane-Stewart, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry, 1812. Oil on canvas; (56 1/2 x 46 3/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 6171. Purchased with help from the Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, 1992. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (American). Coat, ca. 1815. Linen. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997.508. Purchase, NAMSB Foundation Inc. Gift, 1997. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 4 - Sir Martin Archer Shee (Irish, 1769-1850). William Roscoe, 1815-1817. Oil on canvas; (91.73 x 65.55 in). Liverpool, U.K.: Walker Art Gallery, WAG 3130. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 5 - Rudolph Ackermann (English, 1764-1834). Fashion Plate: "Full dress of a Gentleman" for "The Repository of Arts", 1810. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

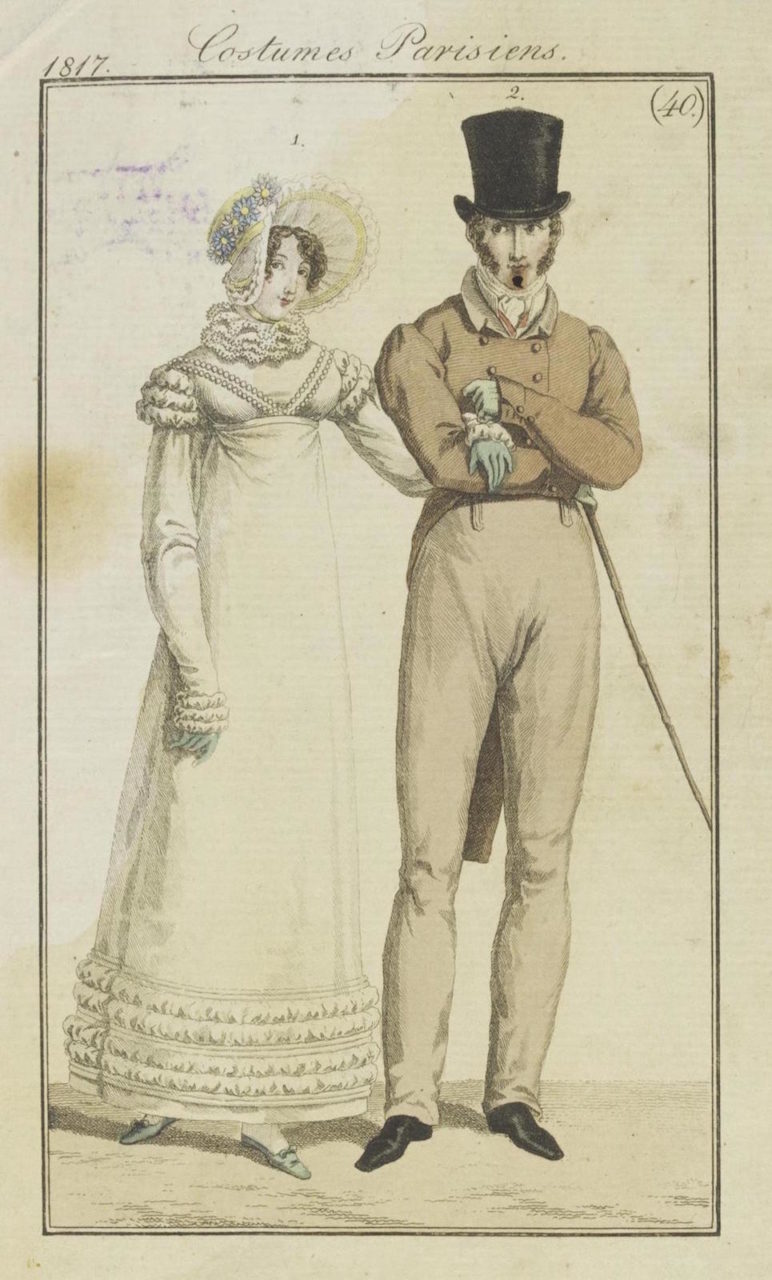

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (French). Fashion Plate: Costume Parisien, 1817. Hand-colored engraving. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, E.22396:95-1957. Given by the House of Worth. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 7 - Thomas Sully (American, 1783-1872). Daniel La Motte, 1812-1813. Oil on canvas; (36 3/8 x 29 in). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1983.76. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ferdinand La Motte III. Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum

A man’s ensemble was completed with several pieces. Shirts were white with ruffled or pleated fronts, and very high stand collars that skimmed the jaw (Tortora 319; le Bourhis 112). Neckwear was a crucial element of a man’s wardrobe. The main form was the cravat, a large square of fine muslin or silk, folded cornerwise and carefully tied in a variety of arrangements (Fig. 7) (Waugh 119). Dangling seals and fobs at the waist, which were attached to the watch tucked into a pocket in the waistband, were a hallmark of early nineteenth-century menswear (Ashelford 186; Cumming 83). The top hat was the favorite form of headwear, available in a wide range of shapes and colors (Fig. 1, 6) (Ginsburg 85; le Bourhis 112-113). For evening, the chapeau-bras was a stylish choice, flat and foldable to be carried under the arm (Fig. 5) (Davidson 200, 226).

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Infants of the 1810s were dressed in very long, back-fastening dresses featuring a low neckline and short sleeves, and a simple baby cap (Buck 46, 50). White cotton was the usual material as it allowed for easy laundering. When a baby reached about six months old, the gowns shortened to calf-length to allow movement (Callahan). During toddlerhood, boys and girls were dressed in similar clothes. Both wore calf-length dresses, often called frocks, sometimes with trousers peeking out beneath (Fig. 1). These would later be referred to as drawers or pantalettes. Like womenswear, toddler dresses usually featured low, square necklines, puffed sleeves, and a very high waistline (Buck 66, 106; Ashelford 280-281).

Boys passed through roughly three stages of dress, beginning with the frocks of toddlerhood, discussed above. Then, at about age three, a boy began wearing the skeleton suit, a garment with origins in the eighteenth century. It consisted of loose trousers buttoned onto a very short jacket, completed with a white shirt featuring an open collar (Fig. 2). Receiving his first pair of trousers was a rite of passage for a boy called breeching, a tradition that continued through the rest of the century (Callahan). A boy remained in the skeleton suit until about age ten, although a variation was sometimes worn by older boys in which the short jacket was worn outside the trousers. Then, through their early teenage years, boys wore short, round jackets and waistcoats with closer-fitting trousers or pantaloons. Sometimes the jacket had shortened, squared tails in the back, especially for boys of thirteen or older (Fig. 3). By fifteen years old or so, a boy made the full transition to men’s styles, switching the open collar for a cravat and wearing adult tailcoats. (Buck 194-196; P. Cunnington 172-174; Callahan).

Throughout their childhood, girls wore high-waisted dresses much like their mothers’ dresses, except that they were slightly shorter. During the 1810s, girls’ hems began to shorten to somewhere between the lower calf and the top of the shoes (P. Cunnington 194-197; Tortora 322). The fashionable narrow skirt allowed young girls to go without stays or layers of petticoats. Instead, they usually wore a single petticoat and drawers, which were just barely visible under the newly shortened hemline (Fig. 4) (Torell; Buck 211). Dresses for morning wear could be of a printed cotton, but afternoon or best dresses were in fine white muslin (Rose 38-41). Eye-catching sashes could be tied at the waist, and were a stylish way to introduce color into a girl’s outfit (P. Cunnington 195). Like womenswear, nearly-transparent nets could be worn over colored silk slips as well. A girl completed her ensemble with outerwear and millinery like those of grown women: spencers (Fig. 5), pelisses, shawls, high-crowned hats, and face-shielding bonnets (Buck 207, 212-217). By sixteen years of age, a girl was considered a young woman, lowering her hem to the floor (P. Cunnington 194).

Fig. 1 - Thomas Lawrence (English, 1769-1830). Lydia Elizabeth Hoare, Lady Acland, with Her Two Sons, Thomas, Later 11th Bt, and Arthur, 1814-1815. Oil on canvas; 152.5 x 117 cm. Exeter, U.K.: National Trust, Killerton, 922303. Purchased by private treaty sale, 1991. Source: Art UK

Fig. 2 - Sir Henry Raeburn (Scottish, 1756-1823). William Stuart Forbes, elder son of Sir William Forbes of Pitsligo, 1802 - 1826, 1809-1813. Oil on canvas; 135.26 x 109.86 cm. Edinburgh: National Galleries Scotland, NG 2882. Accepted in lieu of Inheritance Tax by HM Government from the Forbes of Pitsligo Collection, and allocated to the National Galleries of Scotland, 2018. Source: National Galleries Scotland

Fig. 3 - Henry Thomson (English, 1773-1843). Master Roger Mainwaring, ca. 1810. Oil on canvas; 190.5 x 108.5 cm. Denver, Colorado: Denver Art Museum, 2019.5. Gift of the Berger Collection Educational Trust. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 4 - Alfred Edward Chalon (Swiss, 1780-1860). Portrait of a Woman with Two Children in a Domestic Interior, ca. 1815-1820. Oil on canvas; 35 x 40 cm. London: Museum of the Home, 34/1982. Bequeathed by G. C. Allen through the Art Fund, 1982. Source: Art UK

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (English). Girl's dress and Spencer Jacket, ca. 1817. Silk and wool. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, AC1997.191.40.1-.2. Gift of Helen Larson. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

References:

- Ashelford, Jane. The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society, 1500-1914. London: National Trust, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/243850605

- Buck, Anne. Clothes and the Child: A Handbook of Children’s Dress in England, 1500-1900. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/243852072

- Byrde, Penelope. Nineteenth Century Fashion. London: Batsford, 1992. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/26300526

- Callahan, Colleen R. “Children’s Clothing.” in The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 145-149. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Bloomsbury Fashion Central via the New York Public Library. http://dx.doi.org.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0003223.

- Cumming, Valerie ed., The Dictionary of Fashion History. New York: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1003643284

- Cunnington, C. Willett. English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Guide with 1,117 Illustrations. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868281120

- Cunnington, Phillis, and Anne Buck. Children’s Costume in England: From the Fourteenth to the end of the Nineteenth Century. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1978. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/174334043

- Davidson, Hilary. Dress in the Age of Jane Austen: Regency Fashion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1115106379

- Foster, Vanda. A Visual History of Costume: The Nineteenth Century. London: BT Batsford, 1984. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28405843

- Fukai, Akiko, ed. The Collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute: Fashion, A History from the 18th Century to the 20th Century. Kyoto: Taschen, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/81452017

- Ginsburg, Madeliene. The Hat: Trends and Traditions. London: Studio Editions, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/22914760

- Jensen, Heather Belnap. “Parures, Pashminas, and Portraiture, or, How Joséphine Bonaparte Fashioned the Napoleonic Empire.” in Fashion in European Art: Dress and Identity, Politics and the Body, 1775– 1925. Edited by Justine De Young, 36-59. London/New York: I.B.Tauris, 2017. Bloomsbury Fashion Central via The New York Public Library. http://dx.doi.org.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/10.5040/9781350986381.ch-002

- Johnston, Lucy, Marion Kite, Helen Persson, Richard Davis, and Leonie Davis. Nineteenth Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publications, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/61302743

- Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/966352776

- le Bourhis, Katell, ed. The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire 1789-1815. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/60131971

- Mackrell, Alice. Art and Fashion: The Impact of Art on Fashion and Fashion on Art. London: B T Batsford, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/316202486

- Rose, Clare. Children’s Clothes: 1750-1985. London: BT Batsford, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/317672212

- Stuart, Andrea. The Rose of Martinique: A Life of Napoleon’s Joséphine. London: Grove/Atlantic, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/948040948

- Torell, Viveka Berggren. “Children’s Clothes.” in Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: West Europe. Edited by Lise Skov, 462-268. Oxford: Berg, 2010. Bloomsbury Fashion Central via The New York Public Library. http://dx.doi.org.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch8076

- Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865480300

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes: 1600-1900. New York and London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927414537

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1810-1819

Rulers:

- England: George III (1760-1820)

- France:

- Napoleon (1804-1814)

- Louis XVIII (1815-1824)

- Spain

- Joseph Bonaparte (1808-1813)

- Ferdinand VII (1808-1806 and 1813-1829)

- United States

- James Madison (1809-1817)

- James Monroe (1817-1825)

Events:

- 1810 – British-born Edward Cartwright had patented the first power loom in 1785, but the design was in need of modification. Between then and the early 19th century it underwent improvements and by 1820 was commonly used in both Britain and the United States.

- 1812-1814 – The War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain.

- 1813 – Jane Austen’s novel Pride and Prejudice is published.

- 1815 – Napoleon is defeated at the Battle of Waterloo and exiled to the island of St. Helena.

- 1819 – Spain ceded Florida to the United States.

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Fashion Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 19th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.