OVERVIEW

The 1620s saw the adoption of leg-of-mutton sleeves in both men’s and womenswear; while men’s clothing achieved an elegant, longer line, women’s dress became high-waisted and fuller.

Womenswear

The 1620s witnessed a slow transformation in womenswear, as François Boucher explains in A History of Costume in the West (1997):

“Women’s costume also became simplified; the farthingale disappeared; a soft collar replaced the ruff and standing collar; the paned padded sleeves of the undergown are tied at elbow height; the black gown skirt opens over the light-colored underskirt.” (259)

Anthony van Dyck’s portrait of a lady with a fan (Fig. 1) perfectly embodies these new stylistic trends. She no longer wears a farthingale, but has gained tremendous volume in her sleeves, which are paned leg-of-mutton sleeves made of a soft white satin. The volume of the sleeves is moderated somewhat by a ribbon that cinches the sleeve in around the elbow in a decorative bow. That bow was known as a virago and the sleeves are often referred to as virago sleeves (Boucher 272). Norah Waugh in The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600-1930 (1968) comments that: “The 1625 gown was made from damask, velvet, silk, etc. and seems invariably to have been black, with the under-bodice, sleeves and petticoat made usually of a light-coloured contrasting material” (29). The van Dyck portrait is a good example of this contrast between gown and bodice/petticoat color. Notably the gown was now considered an integral part of the outfit rather than an additional layer (in this case it’s secured by a white sash) and so the term ‘gown’ began to be used for the entire outfit from about circa 1625 onward (Cunnington 80).

Jacques Callot’s etching of a masked noble woman (Fig. 2) shows another version of this new silhouette, though her collar seems to still be somewhat wired to stand out from her shoulders rather than lying flat as van Dyck’s woman’s does. The wearing of masks became fashionable in this period as Boucher explains: “The mask, which was held in place by a button gripped between the teeth or by a thick handle pushed into the hair, protected the complexion or preserved the wearer’s incognito” (270).

Fig. 1 - Sir Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599- 1641). Lady with a Fan, ca. 1628. Oil on canvas; 109.7 x 97 cm (43 3/16 x 38 3.16 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1957.14.1. sold March 1932 to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, New York, gift 1957 to NGA. Source: NGA

Fig. 2 - Jacques Callot (French, 1592- 1635). Masked Noble Woman, ca. 1620-1623. Etching. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1969.15.82. R.L. Baumfeld Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 3 - Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640). Portrait of Anne of Austria, Queen of France, ca. 1622-25. Oil on canvas; 120 x 96.8 cm (47-1/4 x 38-1/8 in). Pasadena: Norton Simon Museum, F.1965.1.059.P. The Norton Simon Foundation. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (British). Gertrude Sadler, Lady Aston, ca. 1620-3. Oil on canvas; 227.3 x 133.4 cm. Headquarters in London: Tate, T03030. Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery, the Art Fund and the Pilgrim Trust 1980. Source: Tate

Fig. 5 - Daniel Mytens the Elder (Dutch, 1590-1642). Portrait of a Young Noblewoman, ca. 1629. Oil on canvas; 195.6 x 123.2 cm (77 x 48 1/2 in). Pasedena: The Norton Simon Museum, F.1965.1.042.P. Source: Norton Simon

Peter Paul Rubens’ portrait of Anne of Austria (Fig. 3), Queen of France, features the full sleeve volume then fashionable, though here her sleeves are not paned, but instead have open seams closed by pearls with the lining, or perhaps her chemise, puffed out in the gaps. The neckline remains low and framed by a Medici collar as was typical in France. The front of the bodice is filled by a stiff stomacher, “which was richly decorated and embroidered, formed a bowed curve in front, highly fashionable from 1620 to 1635” (Boucher 271). She wears an ermine-lined mantle and her blue bodice and skirt are covered with the French fleur-de-lys.

English women were slower to adopt the new sleeve volume, seemingly preferring open seams to paned or virago sleeves. As Hill describes in his History of World Costume and Fashion (2011): “Skirts draped naturally from the waist to the floor. The bodice was reduced in size and shortened with a raised waistline…. Sleeves were short, cropped to the elbow in some designs” (409). A portrait of Gertrude Sadler, Lady Aston (Fig. 4), captures well this new state of affairs, with a new very high waistline paired with the very low rounded neckline that had been popular in the 1610s. Her ruff-like collar is supported by a wire frame that tilts it up behind her head. Notably her feet are still visible, which would become less common as the decade progressed.

Daniel Mytens the Elder’s portrait of a young noblewoman (Fig. 5) captures a similar high-waisted look, here further emphasized by the addition of a white lace apron. Indeed, in the 1620s, “lavish quantities of elaborately patterned lace were used for every accessory, from cuffs and collars to handkerchiefs and boot hose. Flemish bobbin lace was widely available, but the new fashions benefited every lace-making center in Europe” (Brown 118). This woman’s sleeves are even shorter, but she wears the same tilted lace-edged ruff collar, though here with a thin strand of hair trailing over it. This sort of display was sometimes called a love lock and was associated with King James I of England; George Villiers wears a love lock in several portraits as well (see “Fashion Icon” section below). This has led some to speculate that the portrait represents Elizabeth Stuart (1596–1662), who was “King James’s first-born and only surviving daughter, … largely based on the single lock of hair hanging down from her neck, which was Elizabeth’s personal hallmark.” However, as the Norton Simon Museum adds, “Many of the members of her court and beyond adopted the whimsical hairstyle.”

Fig. 6 - Paul van Somer I (Southern Netherlandish, 1576-1622). Portrait of a Young Lady, ca. 1620. Oil on panel; 90.5 x 70.5 cm (35.6 x 27.7 in). Denver Art Museum, Berger Collection #33. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 7 - Daniel Mytens (Dutch, 1590-1647). Elizabeth Leicester, 1620s. Oil on canvas; 116.9 x 86.4 cm. Knutsford, Cheshire: Tabley House, 210.3. Source: Art UK

Fig. 8 - Maker unknown (English). Waistcoat, 1620-1625. Linen embroidered with silk. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.4-1935. Source: V&A

Fig. 9 - Rodrigo de Villandrando (Spanish, 1588-1622). Isabel de Borbón, Wife of Philip IV, ca. 1620. Oil on canvas; 201 x 115 cm. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, Poo7124. Legacy Valentín Carderera, 1880. Source: Museo Nacional del Prado

Fig. 10 - Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). A Genoese Lady with her Child, ca. 1623-25. Oil on canvas; unframed: 217.8 x 146 cm (85 3/4 x 57 1/2 in). The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1954.392. Gift of the Hanna Fund. Source: The Cleveland Museum of Art

Paul van Somer I’s portrait of a young woman (Fig. 6) shows another variant of this look with a low, squared neckline now accented by a fan-shaped sort of Medici collar titled up behind her head. As Valerie Cumming notes in A Visual History of Costume: The Seventeenth Century (1984), this was typical of the “late transitional phase of fashionable Jacobean female dress with a high waistline but no agreed style of collar or neckwear” (38).

Elizabeth Leicester (Fig. 7) wears a striking black and white version of this kind of dress, with the open seam of her sleeve revealing a lace underlayer. Notably she has paned upper sleeves, but they have no volume to them. A similarly monochromatic waistcoat is in the Victoria & Albert Museum collection (Fig. 8). The museum describes its typical shape and the inspiration for its designs:

“The high waistline and narrow sleeves, open at the front seam, are characteristic of women’s waistcoats of the early 1620s. The blackwork embroidery is of exquisite quality and is worked in a continuous pattern throughout the body of the garment. A group of interlocking curling stems enhanced with a garden of roses, rosebuds, peapods, oak leaves, acorns, pansy and pomegranates, with wasps, butterflies and birds, make up the embroidery design. The extremely fine speckling stitches create the shaded effect of a woodblock print. This style of blackwork is typical of the early seventeenth-century and thought to have been inspired by the designs from woodblock prints that the embroiderers were using. The waistcoat is unlined and embellished with an insertion of bobbin lace in black and white linen at the back of each sleeve, and an edging of bobbin lace in the same colours.”

While lace caps had been worn with waistcoats in the 1610s, by 1625 fashionable married women abandoned the wearing of a cap and wore their hair elaborately styled, uncovered, or adorned with a feather or with a hat.

In Spain fashions remained quite similar to earlier decades of the 17th century; the Spanish farthingale was still worn with a large ruff as can be seen in a portrait of Isabel de Borbón, wife of Philip IV (Fig. 9). In Genoa, which was allied with Spain, one finds similar fashions, though the farthingale has been discarded as in van Dyck’s portrait of a Genoese woman with her child (Fig. 10). (See also this close analysis of a different Genoese noblewoman of the same period also painted by van Dyck).

Fashion Icon: George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham (1592-1628)

Fig. 1 - Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). Double portrait of George Villiers, Marquess and his wife Katherine Manners, as Venus and Adonis, ca. 1620. Oil on canvas; 222.9 x 163 cm (87.7 x 64.1 in). Private Collection. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 2 - Paul von Somer I (Flemish, 1576/1578- 1622). George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, before 1622. Oil on panel; 87x 74.9 cm. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts. gift of Mr. and Mrs. Walter Weber in memory of Mrs. Weber's father and mother, Judge and Mrs. F. C. Proctor. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 3 - Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577- 1640). George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 1625. Private Collection. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 4 - Michiel van Mierevelt (Dutch, 1567-1641). Portrait of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 1625-1626. Oil on panel; 69.5 x 57.5 cm. Adeliade: Art Gallery of South Australia, 0.2115. South Australian Government Grant 1967. Source: Wikipedia

George Villiers rose very quickly in the court of King James I. He was said to have attracted the king’s attention at a hunt in 1614, after which money was apparently raised to buy him new clothes. He became cupbearer to the king, then was knighted as a Gentleman of the Bedchamber, shortly thereafter he was elevated to the peerage and made a Knight of the Garter, before becoming Earl, then Marquess and finally Duke of Buckingham—a tremendous rise in less than a decade (Wikipedia). He was clearly a favorite of the king and, some have argued, his lover.

What isn’t disputed was his physical attractiveness, as Pauline Gregg details in King Charles I (1984):

“‘He was one of the handsomest men in the whole world’, wrote Sir John Oglander. ‘From the nails of his fingers – nay from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head, there was no blemish in him. The setting of his looks, every motion, every bending of his body was admirable.’” (49)

He appeared at court as a dancer in masques from 1615 and tutored James’s son, Charles I, the crown prince, in dance. Rubens’ rather astonishing portrait of Villiers and his wife Katherine Manners as Venus and Adonis (Fig. 1) gives some hint of his bodily grace and handsomeness. Gregg quotes another contemporary as having written of Villiers:

“All that sat in the Council looking steadfastly on him, saw his face as if it had been the face of an angel…. He was the handsomest bodied man in England; his limbs so well compacted, and his conversation so pleasing, and of so sweet a disposition.” (49)

He was also a lavish dresser as a portrait by Paul von Somer I details (Fig. 2). His face has perhaps more of a devilish cast to it here, though it floats upon an elaborate lace standing collar. His red satin doublet is paned to reveal a gold brocade fabric lining, with the panes edged by pearl buttons and seed pearl eyelets. He wears a sort of sash made of perhaps ten strands of pearls that he has tucked through one of the doublet panes across his torso. In an era before cultured pearls, this represented a nearly unimaginable display of wealth. In this portrait (and also Fig. 4), we see the love lock, or dangling strand of hair discussed above, displayed on the standing band.

In contrast, in Rubens’ portrait (Fig. 3) Villiers is quite simple dressed in a paned black satin doublet with a white satin lining; his standing collar has lace only along the edge. The blue sash signals his knighthood. His face has the pleasing character so often ascribed to it. Upon King James’ death in 1625, Villiers remained highly placed at court through his friendship with now King Charles I. He was sent on diplomatic missions to France and the Netherlands, where he made quite an impression (and commissioned several portraits). Diana de Marly in Fashion for Men: An Illustrated History (1985) describes the impact of his lavish dressing:

“The showiest person at the English court was James I’s favourite George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham… On his visits to France and the Netherlands in 1625-6, the new duke was resolved to outshine all other mortals. A Parisian reported: ‘It must be confessed that the Duke of Buckingham had the finest outfit one could see in a lifetime. I am moved to describe it. It was of gris-de-lin coloured satin, embroidered with pearls, the embroidery being in bands: the pearls in the middle of the band might be worth ten crowns apiece, those on the edge, twenty at least. The buttons were pearls of twenty crowns in value, the buttonholes of pearl embroidery and the tags were also made of pearls in graduated sizes. He had a chain which when six times round his neck, made of pearls of immense value. His girdle was worth at least thirty thousand crowns. In his hat was a plume of heron’s feathers at the base of which was a badge of five very large diamonds and three superb pearl-shaped pearls. From his ear hung a large pearl with a great diamond at the ear-clasp, but this scarcely showed because his hair was so long and so much curled as to hide it.” (46)

One gets a sense of this extravagance in the portrait by Michiel van Mierevelt (Fig. 4), where Villiers again wears the pearl strands seen earlier and a pearl-encrusted doublet of very similar design. It should be noted his family was equally fashionable, as a portrait from 1628 attests (see Fig. 2 in the Children’s wear section below). The family portrait was painted the same year that the Duke, who was a much better dresser than he was a Lord Admiral, was assassinated by a disgruntled army officer.

Menswear

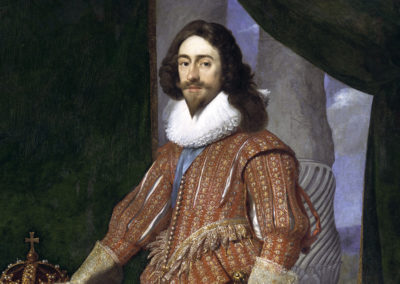

Menswear underwent similar shifts as those seen in womenswear in the 1620s; doublets gained paned leg-of-mutton sleeves and came down to a point in the center front. Softer collars became fashionable. These changes are thought to have be pioneered in France, as a surviving doublet in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art attests (Fig. 1). It has paned sleeves and a paned torso and wide basques that create a point in the front. England, however, had better portrait painters and so our best evidence of these French fashions is at the English court, where they adopted “after 1625 … virtually the same costume as in France: slashed doublets, Venetians, falling collars for men” (Boucher 273). Venetians were long-lined trunk hose that closed at the knee, and sometimes buttoned down the side, but by this period were more commonly referred to as breeches. King Charles I (Fig. 2), like his friend the Duke of Buckingham (See “Fashion Icon” above), was quite fashionable in his dress as the Royal Collection details:

“Charles wears a doublet of brownish plum-coloured silk with a sharply pointed V-shaped waistline. Below the waist at the front are four stiffened laps decorated with silver braid and gold silk satin. The doublet is paned across the chest, revealing a gold coloured silk lining, and the sleeves are constructed in stiffened strips of the same fabric. Tightly spaced buttons stretch from neck to waist ensuring the doublet retains its tight fit across the torso. Around the waistline are ribbon bows tipped with metal aglets. By this stage they are probably purely ornamental, a vestigial feature reflecting the earlier fashion for doublet and breeches to be laced together through holes in the waistband.”

Notably the French doublet in the Met’s collection (Fig. 1) has holes for just such ribbon bows. King Charles I wears a mostly fallen ruff about his neck, as had become fashionable as Hill explains:

“the soft ruff became increasing[ly] popular for the upper middle classes in the 1620s. It was basically constructed as layers of ruffled linen that lay softly over the shoulders. Some soft ruffs were layered with lace or edged with lace trim, and others were arranged into soft, accordion pleats.” (400)

A lace-edged three-layered ruff made of linen from this period survives in the collections of the Swedish Royal Armoury (Fig. 3).

James Hamilton (Fig. 4), 1st Duke of Hamilton, an ardent supporter of Charles I, dresses in a similar style, though he wears the more fashion-forward floppy falling band instead of a fallen ruff. As Hamilton’s portrait attests: “longer hair was newly fashionable for young courtiers” (Cumming 42); a pointed beard—now called a van Dyck beard after the artist who painted so many of them—and a small mustache were also common (Figs. 2, 6, 7). In Millia Davenport’s memorable phrasing it was “the age of long locks, lace and leather” (505). Both the King and the Duke wear knee-high leather boots with deep cuffs and spurs.

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (French). French doublet, early 1620s. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989.196. The Costume Institute Fund, in memory of Polaire Weissman, 1989. Source: The MET

Fig. 2 - Daniel Mytens (Netherlandish, 1590- 1647). Charles I, 1628. Oil on canvas; 219.4 x 139.1 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN404448. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown. Ruff, 1620s. Ruff of three layers of fine white linen, tightly gathered at the neckline, trimmed with bobbin lace; diameter: 40 cm. Stockholm: The Royal Armoury (Swedish: Livrustkammaren), LRK 33076. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 4 - Daniel Mytens (Dutch, 1590-1647). James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton, 1629. Oil on canvas; 221 x 139.7 cm. National Galleries Scotland, PG 2722. Purchased with help from the Art Fund, the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Pilgrims Trust 1987. Source: National Galleries Scotland

Fig. 5 - Daniel Mytens (Dutch, 1590-1647). Portrait of James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, Later 3rd Marquis and 1st Duke of Hamilton, 1623. Oil on canvas; 200.7 x 125.1 cm. Headquarters in London: Tate, NO3474. Presented by Colin Agnew and Charles Romer Williams 1919. Source: Tate

Fig. 6 - Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (Flemish, 1561/1562-1635/1636). Sir Thomas Parker of Ratton, ca. 1620. Oil on canvas; 213.5 x 134.5 cm. Plymouth: Art UK, 872163. accepted in lieu of death duties on the estate of Edmund, 4th Earl of Morley; transferred from HM Treasury, 1957. Source: Art UK

While the 1629 portrait (Fig. 4) embodies the fashions of the end of the decade (and foreshadows fashions of the 1630s), an earlier portrait of Hamilton at age 17 (Fig. 5) reveals the fashions of the first part of the decade. Here the brightly colored hose popular in the 1610s are still being worn, as are shoe rosettes and ribbon garters. His black satin doublet and trunk hose are pinked all over, but otherwise only decorated by the metallic points at his waist and his silver sword belt.

Sir Thomas Parker of Ratton (Fig. 6) wears not bright red hose, but bright red slops (very full cut trunk hose) and a red cape or cloak. His ribbon garters and shoe rosettes are also red, edged in gold lace; he has a fallen ruff and his doublet comes to a sharp point in the front; though the sleeves retain their earlier slender aspect, they are already paned.

James Hay (Fig. 7), 1st Earl of Carlisle, wears a doublet made of similar fabric, but now with more fullness to the panes, creating a leg-of-mutton effect. In place of slops, he wears Venetian style breeches, still with coordinating ribbon garters and shoe rosettes. He maintains a somewhat more old-fashioned standing lace collar, supported by a wire frame. De Marly describes the look in more detail:

“The Earl’s doublet and breeches have the small-scale patterns that were all the rage in the 1620s. A more sloping shoulderline is emerging with the wing set low. The top half of the sleeve was paned, that is, slashed, and in the 1630s the bottom half was paned too.” (49)

A surviving doublet and breeches in Dresden (Fig. 8) feature the now familiar paning and leg-of-mutton sleeves, as well as the same kind of small-scale patterning seen on the Sir Parker and the Earl. The doublet, part of the pomp dress of Elector Johann Georg I of Saxony, lacks the sharp pointed front that was fashionable elsewhere. At this point Saxony and much of central Europe was consumed with the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) so fashion change in the region slowed.

The Dutch, however, were quicker to adopt the new French trends, as Boucher explains:

“As in France, Dutch men’s costume showed a very noticeable change between 1620 and 1635, and this gradually spread over the rest of Europe: doublets became shorter and tighter and short breeches supplanted … trunk hose. These breeches progressively lengthened to give the silhouette a long, vertical line finished off by moderately flaring boots. The cloak was still worn, but as a cape.” (271)

Frans Hals’ portrait of Willem van Heythuysen (Fig. 9) gives a sense of what this looked like. In keeping with Dutch taste, the fabrics are all black, but they are still subtly patterned; they also establish a strong contrast with the white lace ruff and cuffs and the gold lace and thread of his sword belt and ribbon garters. Though this rejection of color is associated with Protestant piety, it was just as much a status marker as more brightly dyed fabrics as a rich, deep black remained one of the mostly costly colors to achieve through dyeing.

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle, 1628. Oil on canvas; 194.6 x 120 cm (76.6 x 47.2 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 520. Purchased, 1978. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown. Pomp dress of Elector Johann Georg I of Saxony, ca. 1620-1625. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, i. 0011.01. Source: SKD

Fig. 9 - Frans Hals (Dutch, 1582-1666). Portrait of Willem van Heythuysen, ca. 1625. Oil on canvas; 204.5 × 134.5 cm (80.5 × 53 in). Munich: Alte Pinakothek, 14101. Source: Sammlung Pinakotheken

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Sir Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599- 1641). Susanna Fourment and Her Daughter, 1621. Oil on canvas; 172 x 117 cm (67 11/16 x 46 1/16 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1937.1.48. Donated to the NGA by Mellon. Source: NGA

Young infants were dressed in white dresses and often wore necklaces featuring coral, which had been thought to protect babies since ancient times. The Duke of Buckingham’s younger child, his son George, is a good example of both trends (Fig. 2). Other signs of childhood included the pudding hat, a kind of toddler bumper helmet, seen in van Dyck’s portrait of Susanna Fourment and her daughter (Fig. 1). Anna Reynolds describes the pudding cap and its origins in In Fine Style (2013):

“a padded circlet around the head the protected young children of both genders from head injuries when learning to walk – they are named after the pudding sausage to which they bear some resemblance (although another interpretation was that they were believed to stop the brain from turning to pudding).” (133)

Otherwise, as the little girl’s dress suggests, young children were dressed in a similar manner to their parents; note how the Duke’s older child, Mary, is dressed nearly identically to her mother (Fig. 2). One key difference that affected boys was that they remained in skirts (Fig. 3) until the age of breeching, when they then would dress in the style of their fathers. A Flemish portrait of a young boy shows that such garments could be quite lavish; as the Royal Collection Trust explains: “The careful arrangement of the pomegranate patterned fabric across the doublet and skirt would have required excess material and been expensive. The over-large scale of the pattern suggests it may have been remade from adult clothing.”

Fig. 2 - Gerrit van Honthorst (Dutch, 1590-1656). The Duke of Buckingham and his Family, ca. 1628. Oil on canvas; 145.4 x 198.1 cm (57 1/4 x 78 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 711. Purchased, 1884. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 3 - Attributed to the Flemish School. A Young Boy, ca. 1620. Oil on canvas; 88.7 x 58.4 cm. Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 401179. First recorded in the Royal Collection during the present reign. Source: Royal Collection Trust

References

- Boucher, François, Yvonne Deslandres, and John Ross. A History of Costume in the West. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/443676264.

- Brown, Susan, ed. Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. New York: DK Publishing, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/840417029.

- Royal Collection Trust. “Charles I.” Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/16/collection/404448/charles-i.

- Cumming, Valerie. A Visual History of Costume: The Seventeenth Century. 3. London: Batsford, 1984. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/9761398.

- Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Emily Cunnington. Handbook of English Costume in the Seventeenth Century. Boston: Plays, Inc, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/755269282.

- Davenport, Millia. The Book of Costume. New York: Crown Publishers, 1948. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/922657048.

- De Marly, Diana. Fashion for Men: An Illustrated History. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1985. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/752978274.

- Royal Collection Trust. “Flemish School, 17th Century – A Young Boy.” Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.rct.uk/collection/401179/a-young-boy.

- “George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham.” In Wikipedia, January 14, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=George_Villiers,_1st_Duke_of_Buckingham&oldid=935751518.

- Gregg, Pauline. King Charles I. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984. https://books.google.com/books?id=h2v69fUCDxYC.

-

Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950.

- Norton Simon Museum. “Portrait of a Young Noblewoman.” Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.nortonsimon.org/art/detail/F.1965.1.042.P.

- Reynolds, Anna. In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/824726826.

- Victoria and Albert Museum. “Waistcoat.” Accessed January 15, 2020. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O110094/waistcoat-unknown/.

- Waugh, Norah, and Margaret Woodward. The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600-1930. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/894728161.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1620-1629

Rulers:

- France: King Louis XIII (1610-1643)

- England

- King James I (1603-1625)

- King Charles I (1625-1649)

- Spain: Phillip IV (1621-1655)

Carte de l’Europe, 1627. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Events:

- 1618-1648 – Thirty Years’ War

- 1620 – Pilgrims landed in America, establish themselves in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 17th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.