OVERVIEW

In the 1480s the fashions of Florence shine, immortalized in the work of Ghirlandaio and Botticelli, who create an enduring ideal of beauty and demonstrate the connection between contemporary fashion and the dress of the ancient Greeks and Romans. At the same time, Spanish influence continued to spread, introducing a new hairstyle and new outer garments. In northern Europe, we see the last of the angular silhouette as a new one emerges, slender and streamlined for men and molded for women, hinting at the beginnings of corsetry. This decade is the beginning of the transition to sixteenth-century fashion.

Womenswear

In the 1480s all women continue to wear as their basic undergarment the linen chemise, descended from the Roman tunica intima and related to the Greek linen chiton (Boucher 459). In his depictions of Venus and other mythological figures from classical antiquity, Botticelli showed that this connection was understood in the 1480s. The Venus produced by his workshop (Fig. 1), probably shortly after the completion of the famous Birth of Venus now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, wears a filmy, long-sleeved linen garment that is open in the front and does not conceal her idealized body. She strikes a pose derived from ancient sculptures of the goddess (Galleria Sabauda), but her pale skin, golden auburn hair, long neck, sloping shoulders, long torso and graceful arms represent the ideal of beauty of the 1480s. In Botticelli’s Venus and Mars (Fig. 2), the ideal beauty appears again, dressed in a chemise with a second linen garment layered over it, loose and flowing and with long, slit sleeves. It resembles the guarnello, a linen garment opening down the front that could have trimmings in contrasting colors, and long full sleeves, or no sleeves. Due to its comfort and washability, the guarnello was favored by pregnant women, though it was also worn by children and men, probably as informal un-dress worn in the home. It was favored by artists as the “standard form of dress for angels” (Herald 220). To Botticelli the guarnello was the dress of goddesses and nymphs, as seen again in his Portrait of a Young Woman (Fig. 3), which is probably not the portrait of a particular person but yet another depiction of the ideal woman, or a mythological being. The guarnello that she wears as a dress, however, has details rendered in a very realistic manner. It has been decorated with whitework embroidery, using fine white linen or silk thread on the white linen ground fabric; whitework, typically produced by Franciscan nuns in convent workshops (Arthur 189), is one of the steps towards the development of needle lace by the early sixteenth century (Lace Guild). Similarly, the ribbons wound through the hair (benda or bindi), the hair ornament (frenello) made of pearls, and the brooch (fermaglio) that anchors a feather to the top of her fanciful, all’antica hairstyle inspired by ancient sculptures and coins, are all contemporary fashion acccessories (Herald 210-216). The cameo pendant hanging from her gold necklace is a representation of a real ancient Roman gemstone in the collection of Botticelli’s patron, Lorenzo de Medici, who inscribed it with his name (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1 - Sandro Botticelli (Italian, c.1445-1510). Venus, ca. 1485. Turin: Galleria Sabauda, Musei Reali Torino, 172. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2 - Sandro Botticelli (Italian, c.1445-1510). Detail of Venus and Mars, ca. 1485. Tempera and oil on poplar; 69.2 x 173.4 cm. London: National Gallery of Art, NG915. Source: NGA

Fig. 3 - Sandro Botticelli (Italian, c.1445-1510). Idealised Portrait of a Lady (Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci as Nymph), ca. 1480. Tempera on poplar; 81.3 x 54 cm. Frankfurt: Städel Museum, 936. Source: Städel Museum

Fig. 4 - Possibly Dioskourides (Hellenistic, active late 1st century BCE). The Seal of Nero (Apollo, Olympus and Marysas), 30 BCE-20 CE. Intaglio-carved carnelian. Naples: Museo Nazionale Archaeologico, 26051. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Such “portraits” of ideal beauties blending the ancient and the modern in their dress should be compared to more realistic representations of fashions worn in Florence and elsewhere in Italy. Botticelli’s profile Portrait of a Woman (Fig. 5) shows us the next layer worn over the chemise, a dress called the gamurra (Herald 217). This example is made of plain, unpatterned brown fabric, probably wool; it has a low neckline in front and back, exposing bits of the chemise, which is further exposed at the front opening of the dress and through the gaps at the shoulder and elbow, where the sleeve was made intentionally too small to fit the arm. This style was imported into Italy from Spain (Frick 158), spreading via the Kingdom of Naples, which was ruled by the Spanish Aragon dynasty (Scott 141). The gamurra, as seen here, has a fitted bodice with a seam at the waist where the gathered skirt is sewn; both parts of the dress would be lined with a linen fabric (called bambagia in Italy, Herald 210). The waistline of this dress is slightly high at the back, and higher still in the front. The woman’s hair is flattened at the back of her head and held in place wih a linen cap and a finer linen veil. The simplicity of her dress suggests that it is the everyday attire of an upper-class woman, worn like the guarnello in the privacy of home, or that she is not upper-class at all, perhaps a servant (Frick 86), who would not typically be the subject of a portrait.

Davide Ghirlandaio’s Portrait of Selvaggia Sassetti (Fig. 6), the daughter of a Florentine banker, shows us a three-quarter view of a gamurra made of shiny silk, with other indications of luxury like the gold embroidery surround the eyelets of her front-lacing bodice, and the pearl and ruby pendant of her coral necklace. The sleeves of her gamurra have been sewn to the bodice only at the shoulder, allowing the chemise to spill out below. Both her chemise and her fine linen gorget, the kerchief covering her shoulders (Van Buren and Wieck 305), are edged with tiny white loops of embroidery. Her hair is in the style most favored in Florence during this decade, cut short and waved at the sides to cover the ears, with the rest coiled around the back of the head.

The same young woman appears along with her sisters as witnesses to a miracle of Saint Francis, in a fresco by Domenico Ghirlandaio completed a few years earlier in the Sassetti Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Trinita in Florence (Fig. 7). Women rarely ventured out in public without an outer garment over their gamurre (Frick 162). Here Selvaggia Sassetti, who was only about fifteen years old in this portrait, wears a blue cioppa, a long-sleeved outer garment typically worn in winter (Frick 163). The sleeves of this cioppa have been pushed up above the elbow, revealing the sleeves of the dark red gamurra worn underneath. The cioppa has a scoop neckline, filled in with a linen gorget, and a train at the back that has been turned up and caught by the belt, which is placed at a high waistline. Selvaggia’s older sister Elisabetta stands behind her, dressed in a similar dark red gamurra but wearing a different outer garment, the giornea (Herald 218), a sideless cape that opens partially down the front, where we can see the front lacing of her gamurra; her sleeves too are made in the Spanish split style, with the upper part of the sleeve trimmed with the same fabric used for the giornea, a beautiful patterned voided velvet or bicolored damask. This giornea, like her sister’s cioppa, has a looped-up train, though it is not belted in the front.

Fig. 5 - Sandro Botticelli (Italian, c.1445-1510). Portrait of a Woman,, ca. 1485. Tempera on wood; 61 x 40.5 cm. Florence: Palazzo Pitti, Inv. 1912 n. 353. Source: Uffizi

Fig. 6 - Davide Ghirlandaio (Italian, 1452–1525). Portrait of Selvaggia Sassetti, ca. 1487-88. Tempera on wood; 57.2 x 44.1 cm (22 1/2 x 17 3/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 32.100.71. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931. Source: MMA

Fig. 7 - Domenico Ghirlandaio (Italian, 1449-1494). Detail from The Resurrection of the Child, 1483-5. Fresco. Florence: Santa Trinita. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 8 - Domenico Ghirlandaio (Italian, 1449-1494). Detail from The Birth of St. John the Baptist, 1485-90. Fresco. Florence: Cappella Tornabuoni, Santa Maria Novella. Source: Wikimedia Commons

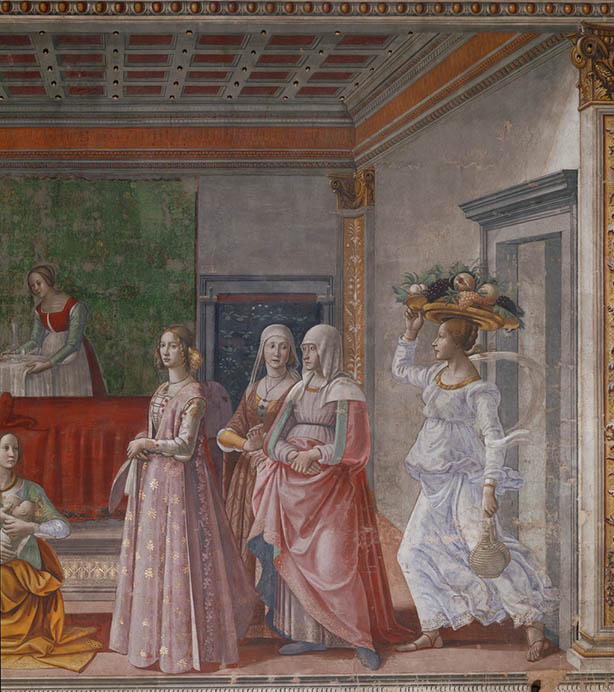

The giornea was usually the outer garment of choice for the spring and summer months (Frick 162) and since it was sleeveless and open at the sides, it allowed a view of the gamurra underneath. The young woman who witnesses the scene in Ghirlandaio’s The Birth of St. John the Baptist (Fig. 8) wears the two garments in contrasting patterned silks. The gamurra is in white satin brocaded or embroidered with small red flowers and gold pomegranate motifs. The bodice fronts were cut so narrow in the front that the chemise is exposed almost to the waistline. The giornea is a lavender-pink silk, brocaded with gold pomegranates, trimmed with gold embroidery along its partial front opening, and dagged along the edges of the back panel. Dagging was a decorative cutwork technique that was more rare in the 1480s than in earlier decades (Van Buren and Wieck 302); in this case the silk has been cut into the shape of oak leaves. This giornea too has a long train, which the young woman carries over her right arm. She has been variously identified as Ludovica Tornabuoni, daughter of the patron Giovanni Tornabuoni, or his daughter-in-law, Giovanna degli Albizzi, who also appears in another scene in the fresco cycle in a more definitive portrait.

The Birth of St. John the Baptist suggests that in the homes of the wealthy, even the servants are fashionably dressed, but fashion is for the young. The middle-aged woman, with the traditional married lady’s veil on her head, is participating in the trend for split sleeves and bodices, but the older woman next to her, wrapped up in a mantle (mantello, Herald 222) is not. Some historians have observed that marriageable girls and brides were “sacred dolls,” put on display as symbols of a family’s wealth and honorable status, whereas older women, despite the substantial power they wielded within their families and communities, were literally hidden under veils and mantellos (Frick 207-210). In contrast, the young maid in the background, under her linen apron, wears a red gamurra with green sleeves; both the bodice and the sleeves are splitting open to show the chemise underneath. The servant at the far right, on the other hand, transcends the trends of the 1480s. She seems to be coming in from the ancient world, bringing fruit and wine, dressed in a Roman tunic. This fresco cycle in the main apse at the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence was completed during the latter half of the decade. In addition to showing Florentine fashion for young women at its most luxurious, it shows a slightly narrower, more slender silhouette. By 1488, this trend would be more pronounced in other Italian cities.

Fig. 9 - Lorenzo Costa (Italian, 1460-1535). Detail from Madonna and Child Enthroned with Bentivoglio Family, 1488. Oil on canvas. Bologna: Cappella Bentivoglio, San Giacomo Maggiore. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In Bologna, for example, the Bentivoglio Altarpiece (Fig. 9) in the church of San Giacomo Maggiore includes portraits of the entire family, with the seven young daughters looking very slender and rather stiff in flat-fronted, long-waisted dresses and straight over-garments like long narrow coats with truncated sleeves. Their smooth center-parted hair partly covers their cheeks before being drawn back into a coil, with a hairnet poised at the back of the head. The origin of these styles is Spain (Bernis 52), as seen in a contemporary Spanish manuscript depicting King Ferdinand, Queen Isabella and their daughter Juana (Fig. 10). In the 1490s, Spanish influence on Italian fashion would grow even stronger.

Fig. 10 - Pedro Marcuello (Spanish, 15th century). Recueil de dévotion de la reine Jeanne la Folle d'Espagne, 1488. Manuscript; 21.3 x 14.5 cm. Chantilly: Bilbliothèque de Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly, MS 604 folio 35v. Source: RMN-Grand Palais

Fig. 11 - Hans Memling (Netherlandish, 1430-1494). Young Woman with a Pink, ca. 1485-90. Oil on wood; 43.2 x 17.5 cm. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.7.23. The Jules Bache Collection, 1949. Source: MMA

Fig. 12 - Honoré Bonet (French, fl. 1378-1398). Maximilian of Austria and Mary of Burgundy presenting the Collar of the Golden Fleece, L’Arbre des Batailles..., ca. 1485. Manuscript; 36cm. New Haven: Beinecke Library, Yale University, MS 230, fol. 118r. Source: Yale

In northern Europe during this decade, we see the last of women’s turret headdresses, pointy cones covered with fabric, usually black silk, anchored in place by a curved, fabric-covered wire, and often accompanied by a veil hanging from the top (Van Buren and Wieck 319). In the 1470s the turret had acquired the frontlet, bands of black silk hanging to the shoulders (Van Buren and Wieck 304). In the 1480s the frontlet takes a variety of forms, sometimes longer and wider, and hanging down the back, as in figure 11.

The turret still has the power to distract the eye from other aspects of women’s fashion where significant changes are occurring. The wide belts that used to mark women’s waistlines, for example, are gone in the 1480s; the waistline is elongated and women’s dresses lace in the front across a stomacher, as in the painting of an ideal beauty by Memling (Fig. 11) or they lace at the back, with the front shaped in a smooth, concave curve, as seen in a manuscript illumination depicting the young duchess of Burgundy and her husband, Maximilian of Austria (Fig. 12). The woman holding a flower has sleeves that are narrow and tight but they have not split open to reveal her chemise, whereas that international trend has reached Mary of Burgundy, whose sleeves are slit at the elbow. In both the Memling painting and the manuscript, however, the dresses fit tightly and look stiffened, as if something were molding the body underneath.

Throughout the fifteenth century, probably in continuation of a medieval practice, women and men’s garments have been lined in linen, which protected and reinforced the outer fabric. As fashion demanded that clothing fit more tightly, the linen linings became heavier in weight. In Italy the bambagia linen fabric used for lining was sold by weight (Herald 210). The heavier the lining, the stiffer the garment appeared, which seemed to be the effect that women in northern Europe wanted. While tailors were padding and stiffening men’s doublets to mimic the shape of breastplates, women too may have been provided with a kind of inner armor. In addition to the stiff stomachers that we see in this decade that flattened their curves, they may have worn separate linen under-bodices stiffened with cord or strips of wood. In order to achieve their smooth, molded silhouette, Mary of Burgundy and her ladies in waiting may have worn an early form of the corset, which certainly existed by the sixteenth century (Boucher 446).

Fashion Icon: Giovanna degli Albizzi (1468-1488)

Fig. 1 - Domenico Ghirlandaio (Italian, 1449-1494). Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, 1489-90. Mixed media on panel; 77 x 49 cm. Madrid: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, 158 (1935.6). Source: MNTB

Fig. 2 - Domenico Ghirlandaio (Italian, 1449-1494). Detail of Visitation, ca. 1485-1490. Fresco. Florence: Cappella Tornabuoni, Santa Maria Novella. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Giovanna degli Albizzi (Fig. 1) was a member of a prominent Florentine family and married into an even more prominent one, the Tornabuoni. In 1486, at the age of seventeen, she married Lorenzo Tornabuoni, son of Giovanni Tornabuoni, who was the treasurer to Pope Sixtus IV and uncle to the ruler of Florence, Lorenzo de Medici. After having one son in 1487, Giovanna died in childbirth the following year (Simons 106-107). By the time she was portrayed by Ghirlandaio in the fresco cycle commissioned by the Giovanni Tornabuoni for the church of Santa Maria Novella (Fig. 2), she had already been buried in the church’s crypt, and her husband had married or become engaged to Ginevra Gianfigliazzi, who appears in the fresco immediately behind her (Simons 105-115). Like the other Tornabuoni women represented in the fresco cycle, Giovanna is present as a witness to scenes of pregnancy and childbirth. Ghirlandaio’s half-length portrait, commissioned by her husband Lorenzo, is also believed to be posthumous, completed within a year or so of her death (Simons 115). In both works, Giovanna wears the same ensemble of gamurra and giornea in silks with contrasting woven patterns. The gamurra has a small scale pattern of a golden lattice on a red satin ground, brocaded with green sprigs of white flowers. The golden yellow-and-white giornea has a pattern on a larger scale, that was probably custom-woven for the Tornabuoni since it has one of their family emblems, the diamond, incorporated into it. The other motifs of sunbursts and eagles have no known associations with the family, but Giovanna’s sister-in-law Ludovica is dressed in the same fabric in another scene of the fresco cycle (Frick 211-212).

In both portrayals of Giovanna, Ghirlandaio has painted interlacing “L” motifs, for Lorenzo, at her shoulder (Simons 116). Both the gamurra and giornea are fashionable in style, with the sleeves of the gamurra particularly notable. In addition to the splitting of the sleeve at the elbow, the upper portion has been slit in the back and at the side and tied with gold-tipped red laces at regular intervals, causing small white puffs to form as the chemise underneath is pulled up through the gaps. For the 1480s, this is a very advanced style that we will see again in future decades. However, Giovanna degli Albizzi was remembered not as a fashion leader but as a paragon of beauty and virtue. With her reddish gold hair, pale skin and regular features, she approximated the ideal beauty of the era, and must have reminded Florentines of another beauty who had died young in the previous decade, Simonetta Vespucci (Herald 157-158). Ghirlandaio idealized Giovanna further by elongating her neck and, as studies of the half-length portrait have revealed, adjusting the curves of her body (Simons 115). In Renaissance Florence physical beauty was seen as a moral good; Giovanna’s beauty went hand-in-hand with her virtue, signaled by the rosary and prayer book in the background of the half-length portrait. The pendant that she wears in both portraits, hanging from a black silk cord, was passed on in the family as part of the dowry of Ludovica Tornabuoni (Simons 126).

Menswear

Two portraits of young men allow us to compare these garments and other aspects of men’s fashion in Italy and in northern Europe. In Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man (Fig. 1), we see an unassuming brown wool doublet, decorated only with a fine white fringe at the high neckline and down the front. This doublet is loose-fitting, and has no visible laces down the front. It has sleeves made of the matching brown fabric, but they are attached only under the arm and at the back of the shoulder, so that the shirt is seen through the gap. This is a fashionable feature in this decade, as is his longer, shoulder-length hair. His round hat, a berretta (Herald 210) is probably of red wool.

In the northern painting (Fig. 2), we see a young man of Brussels, who also wears a brown doublet. His has a narrow standing collar and is fastened down the front with gold-tipped laces. Over it he wears an unfitted black outer garment that is lined in a white fabric with a woven pile texture. If the black and the white fabrics are silk, they would have to be imported from either Italy or Spain (Boucher 213). Over his left shoulder there is the trailing end of a black chaperon, which is now a small round hat covered with fabric; in this decade men still wear it or carry it (Van Buren and Wieck 232), even if they already have on a cap, like this young man. The small figure in the background kneeling at the altar gives us a full-length view of the silhouette, still very angular with long black hose and pointed poulaine shoes (Van Buren and Wieck 314). The kneeling man wears a short over-garment with very wide shoulders, supported by maheutres, round cushions in the upper sleeves of his doublet (Van Buren and Wieck 311). However the man in the foreground who is the subject of the portrait does not exhibit this distorted, padded silhouette, and it’s possible that his outer garment is in the new style of the 1480s–slender and full-length, as worn by Maximilian of Austria and his courtiers (Fig. 12 in womenswear), or by Paolo Pagagnotti, a Florentine merchant in Bruges (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1 - Sandro Botticelli (Italian, c.1445-1510). Portrait of a Youth, ca. 1482/1485. Tempera on poplar panel; 43.5 x 46.2 cm (17 1/8 x 18 3/16 in). Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1937.1.19. Andrew W. Mellon Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Young Man Holding a Book, ca. 1480. Oil on wood; 20.6 x 12.6 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 50.145.27. Bequest of Mary Stillman Harkness, 1950. Source: MMA

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Detail of Saint Paul with Paolo Pagagnotti, late 1480s. Oil on wood. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 32.100.63ab. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931. Source: MMA

In Italy too during this decade we see a return to longer over-garments for men, whether the voluminous cioppas and mantellos seen in Florence that recalled the drapery of the Roman toga (Fig. 4), or the narrow open coats worn by the Bentivoglio brothers in Bologna (Fig. 5) In Florence the long-sleeved cioppa in red wool was the established garb of civic leaders (Frick 174), such as Francesco Sassetti (Fig. 6). By the end of the decade it is clear that the new outer garment, in both northern and southern Europe, is the long narrow coat that some historians simply call a “gown” or a “robe” (Van Buren and Wieck 232). Others point out its Spanish origins (Evans 63) and refer to it as the ropa (Anderson 239), and in Italy the word vestito was used (Herald 214-215) for the outer garment that replaced the cioppa. Its advent was undoubtedly the most momentous change in men’s fashion during the decade, since it changed the entire silhouette, but we should also take note of the longer hair, the prevalence of small caps and low-crowned hats, and the end of the unwieldy poulaines.

Fig. 4 - Domenico Ghirlandaio (Italian, 1449-1494). Detail from The Resurrection of the Child, 1483-5. Fresco. Florence: Santa Trinita. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 5 - Lorenzo Costa (Italian, 1460-1535). Detail from Madonna and Child Enthroned with Bentivoglio Family, 1488. Oil on canvas. Bologna: Cappella Bentivoglio, San Giacomo Maggiore. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 6 - Domenico Ghirlandaio (Italian, 1449-1494). Francesco Sassetti and his Son Teodoro, ca. 1487. Tempera on wood; 75.9 x 53 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.7.7. The Jules Bache Collection, 1949. Source: MMA

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Children in the 1480s continued to be dressed in loose-fitting tunics of linen or wool, layered one over the other, during their earliest years. Some sources show both boys and girls wearing linen aprons or pinafores to protect their clothing (Herald 215). In royal and ducal families even very young children were elaborately dressed in adult fashions, as seen in the portraits of five-year-old Philip (Fig. 1), a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece, and three-year-old Margaret (Fig. 2), the children of Maximilian of Austria and Mary of Burgundy. Francesco Sassetti’s young son Teodoro (Fig. 3) wears a green silk doublet with fashionably split sleeves, held together with golden laces, and a beautiful brocaded silk outer garment trimmed with white fur. The Bentivoglio Altarpiece (Figs. 4, 5) provides a look at older children and teenagers, all dressed in an advanced, elegant style.

Fig. 1 - Master of the Magdalene Legend (attr.) (Netherlandish, active c.1480-c.1520). Portrait of Philip the Fair, ca. 1483. Oil on panel; 29.2 x 24.1 cm (11 1/2 x 9 1/2 in). Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1175. John G. Johnson Collection, 1917. Source: PMA

Fig. 2 - Master of the Magdalene Legend (attr.) (Netherlandish, active c.1480-c.1520). Portrait of Margaret of Austria (1480-1530), ca. 1483. Oil on panel; 29 x 20 cm (11.4 x 7.8 in). Château de Versailles, MV 4026; INV 2098; C 338. Source: Joconde

Fig. 3 - Domenico Ghirlandaio (Italian, 1449-1494). Francesco Sassetti and his Son Teodoro, ca. 1487. Tempera on wood; 75.9 x 53 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.7.7. The Jules Bache Collection, 1949. Source: MMA

Fig. 4 - Lorenzo Costa (Italian, 1460-1535). Detail from Madonna and Child Enthroned with Bentivoglio Family, 1488. Oil on canvas. Bologna: Cappella Bentivoglio, San Giacomo Maggiore. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 5 - Lorenzo Costa (Italian, 1460-1535). Detail from Madonna and Child Enthroned with Bentivoglio Family, 1488. Oil on canvas. Bologna: Cappella Bentivoglio, San Giacomo Maggiore. Source: Wikimedia Commons

References:

- Anderson, Ruth Matilda. Hispanic Costume 1480-1530. New York: The Hispanic Society, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/901098027.

- Arthur, Kathleen G. “Images of Clare and Francis in Caterina Vigri’s Personal Breviary.” Franciscan Studies 62 (2004): 177-191. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/7372826493.

- Bernis, Carmen. Trajes y modes en la España de los Reyes Católicos. 2 vols. Madrid: Instituto Diego Velázquez del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1978-1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/570368497.

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume in the West. New York: Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1159814264.

- Evans, Joan. Dress in Medieval France. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/939659457.

- Frick, Carole Collier. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes and Fine Clothing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62133195.

- Galleria Sabauda, Musei Reali Torino. “Venus, Sandro Botticelli” https://www.museireali.beniculturali.it/catalogo-on-line/#/dettaglio/59994_Venere.

- Herald, Jacqueline. Renaissance Dress in Italy, 1400-1500. London: Bell & Hyman, 1981. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/492385048.

- The Lace Guild, “The Craft of Lacemaking: Origins and History.” https://www.laceguild.org/a-brief-history-of-lace.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Portrait of Selvaggia Sassetti, b. 1470.” Catalogue Entry. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436491.

- Simons, Patricia. “Giovanna and Ginevra: Portraits for the Tornabuoni Family by Ghirlandaio and Botticelli.” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 14/15 (2011-2012): 103-135. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5556769121.

- Scott, Margaret. Fashion in the Middle Ages. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1027807923.

- Van Buren, Anne and Roger S. Wieck. Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/741930848.

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1480-89

Rulers:

- France

- King Louis XI (1461-1483)

- King Charles VIII (1483-1498)

- England

- King Edward IV (1471-1483)

- King Edward V (1483-1483)

- King Richard III (1483-1485)

- King Henry VII (1485-1509)

- Spain

- Queen Isabella I (1474-1504)

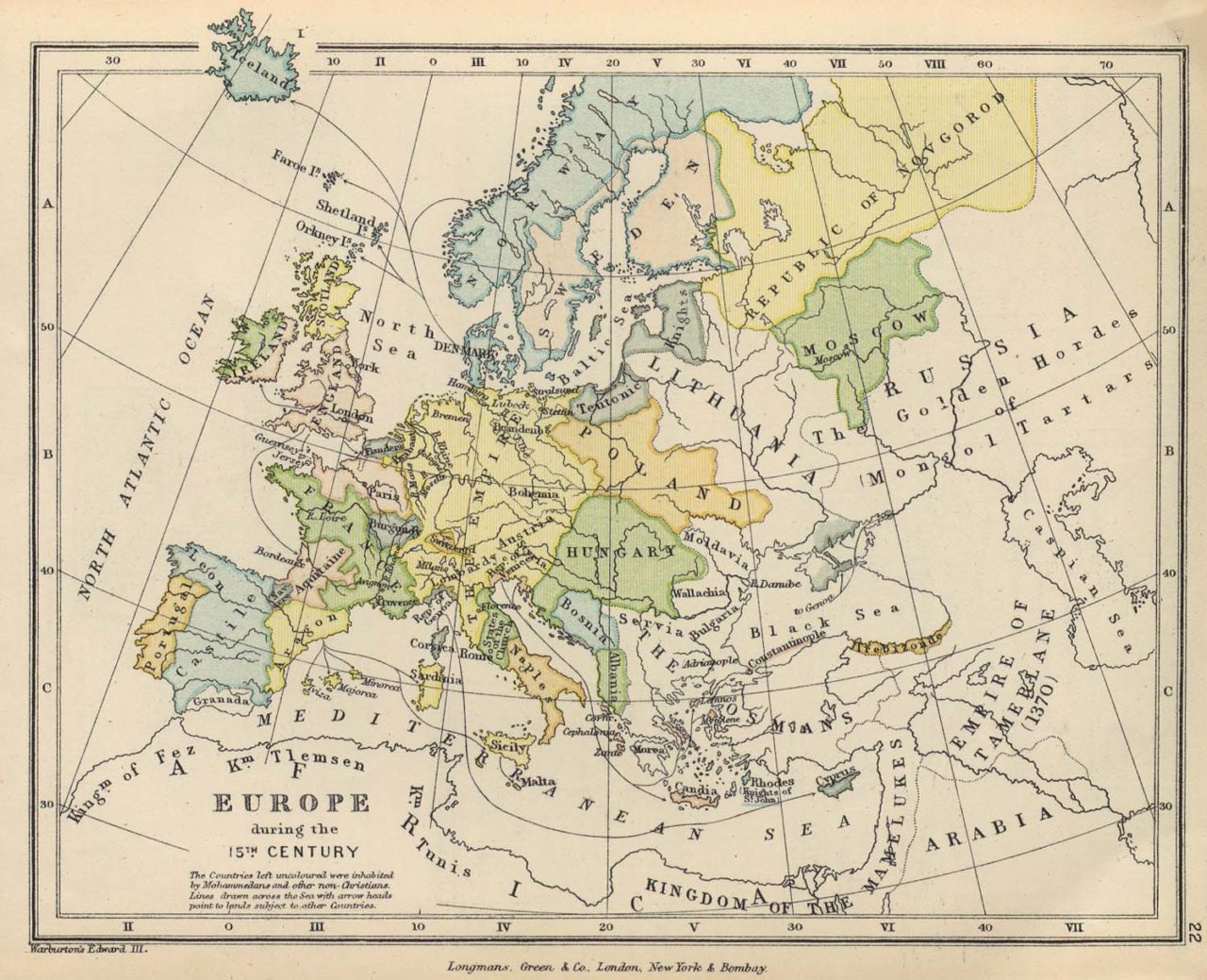

Europe during the 15th Century. Source: University of Texas Libraries

Events:

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 15th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.