OVERVIEW

Fashion during this decade turned away from extravagance and towards simplicity. The elaborate fashions of the court of France that were dominant throughout Europe reached their peak in 1415. In that year, the French defeat at the hands of the English at the Battle of Agincourt, in part because they were over-armored and over-dressed, forced a reckoning. Long houppelandes, bombard sleeves, and decorative dagging declined, and the English and Burgundians took a greater share in fashion leadership.

Womenswear

O ur best source for the fashions of this decade is Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, a beautiful illuminated prayer book commissioned by Jean, Duke of Berry, the uncle of King Charles VI of France. Most of the book’s miniature paintings are the work of the Dutch Limbourg brothers (Paul, Jean and Herman), and are dated between 1410 and 1412 (Van Buren and Wieck 335). The most celebrated pages are the twelve calendar scenes where we see a range of figures and activities, from the labor of peasants to the favorite pastimes of aristocrats, with the Duke’s castles and other landmarks in the distance.

The June calendar page (Fig. 1) is set in Paris. It depicts peasants raking hay in the fields that belonged to the Abbey of St. Germain-des-Prés, on the left bank of the Seine. The two women in the foreground have adapted their dress to their work and the heat of the day. We can see their chemises, the basic undergarment of undyed linen worn by all women (Boucher 445), which would normally be hidden under the next layer, the côte-hardie. The côte-hardie was a long dress with a fitted bodice and a voluminous skirt (Van Buren and Weick 302). These women have loosened the laces and raised the hemlines of their côte-hardies, tucking up the extra length over belts, in order to move more freely. Their côte-hardies have short rather than full-length sleeves. Other features, however, such as the low scoop necklines, reflect the power of fashion and the artists’ desire to make the painting as beautiful as possible by using the most expensive pigments. The woman on the right wears a deep cobalt blue côte-hardie with bright red laces, and her companion wears a delicate, lighter shade of blue. Although dyed textiles were no longer entirely unaffordable to the lower classes, (Piponnier and Mane 88) a peasant possessing a cobalt blue côte-hardie would likely save it for a special occasion. Both women are barefoot, having removed their hose; their headgear consists of pieces of linen, draped around their heads to absorb perspiration and deflect the light of the sun.

Fig. 1 - Limbourg brothers (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). June, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412-1416. Tempera on vellum; 22.5 x 13.6 cm (8.9 x 5.4 in). Paris: Musée Condé, Ms.65, f.6v. Source: Wikimedia Commons

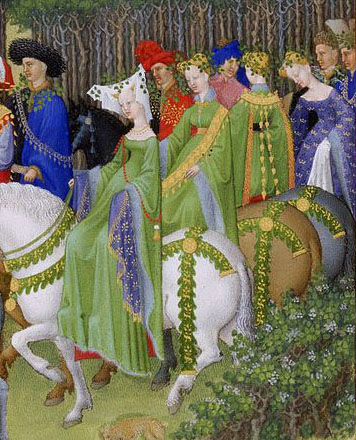

Fig. 2 - Limbourg brothers (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). April, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412-1416. Tempera on vellum; 22.5 x 13.6 cm (8.9 x 5.4 in). Paris: Musée Condé, Ms.65, f.4v. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The April calendar scene (Fig. 2) represents an engagement in the French royal family, likely of Jean de Berry’s granddaughter Bonne d’Armagnac to his nephew, Charles Duke of Orléans, an event which took place in April 1410 (Van Buren and Weick 335). This alliance caused supporters of the Orléans branch of the family to be known as “Armagnacs.” The ladies depicted here wear luxurious and elaborate fashions. One of the women picking flowers wears two layered côte-hardies, the first in cobalt blue with long fitted sleeves, and the second in black with sleeve and hemline borders in white. Hanging from the elbow-length sleeves of the black côte-hardie are strips of fabric called tippets, that would trail behind the wearer and flutter when she moved (Van Buren and Wieck 318). The fiancée in the scene also wears layered côte-hardies, the first painted with gold pigment to indicate a cloth-of-gold, woven with actual gold fibers on a silk foundation. The painter took great care to depict her second côte-hardie, using two shades of blue to indicate a silk voided velvet (Fig. 3) with details brocaded in gold.

Silk and gold textiles with intricate velvet weaves, made in Italy, were some of the greatest luxuries of the age. In order to display the textile to best advantage, this côte-hardie has no sleeves, but rather straight uncut panels hanging from the shoulder and trailing on the ground. In April we can also see examples of the houppelande, an outer garment with a high neckline that was worn by men as well as women (Van Buren and Wieck 307). The flower-picking lady at the right wears a pink houppelande lined in gray, over a black côte-hardie. It has the long funnel-shaped sleeves called bombard sleeves, which were very fashionable during the early years of the decade (Van Buren and Wieck 295). The other example, in black, is worn by the lady witnessing the engagement. Both houppelandes are belted at a high waistline and have turned-down collars. All of the ladies wear variations of the bourrelet headdress, a padded roll that could look very different depending on material and decoration (Boucher 442). The fiancée, for example, wears a bourrelet entirely covered in black feathers and trimmed with vertical feathers in white, red, and gold.

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (Italian). Piece of velvet, 15th century. Cut voided velvet on satin foundation weave; 36.2 x 31.8 cm (14.25 x 12.5 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 08.109.21. Rogers Fund, 1908. Source: MMA

Fig. 4 - Limbourg brothers (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). May (detail), Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412-1416. Tempera on vellum; 22.5 x 13.6 cm (8.9 x 5.4 in). Paris: Musée Condé, Ms.65, f.5v. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The May calendar scene (Fig. 4) reflects the practice of wearing light green, considered the color of vitality and young love, during that month (Van Buren and Wieck 127). Women in the entourage of a high-ranking aristocrat could expect to receive livery gifts of fine green cloth or fashionable green garments to wear in May (Evans 39). The central figure on the white horse has been tentatively identified as Jean de Berry’s daughter Marie, to whom he had granted the title Duchess of Auvergne, and who was Duchess of Bourbon by marriage (Van Buren and Wieck 127). Accompanied by heralds and courtiers, she and her husband are arriving at her father’s Paris residence, the Hôtel de Nesle (Husband 15).

Two of the three ladies accompanying the Duchess wear light green, as does the Duchess herself. Her côte-hardie, likely made of a fine wool lined in grey plush, has bombard sleeves enhanced by blue silk undersleeves, embroidered and fringed in gold. Her long necklace of red coral beads, worn diagonally baldrick style, is similar to that of the fiancée in April. The ladies in green behind the Duchess wear houppelandes, of wool lined in grey plush and with turned-down collars. The houppelandes are nearly identical, suggesting that they were distributed as livery gifts. The ladies are instead distinguished by their accessories — the color of the belt that marked the fashionable high waistline, and the elaborate golden necklaces with long pendants, called carcanets (Van Buren and Wieck 297). This painting also offers us front and back views of the hairstyle known as “a pair of temples,” because the hair was bundled into cones over the temples, where it was held in place by pins and hairnets of fine silk (Van Buren and Wieck 317-318). Atop this hairstyle, the Duchess has the additional decoration of veils of fine white linen, called huves, suspended on wires (Van Buren and Wieck 308). Because it is May, all of the ladies have wreaths and garlands of green leaves interlaced and pinned onto their headdresses.

Les Très Riches Heures is “the utmost and last expression of the extravagant fashions of this time,” according to Van Buren and Wieck (127). During the latter half of the decade, styles that were particularly difficult to wear and expensive to maintain, such as tippets and long bombard sleeves, began to fall out of favor.

Fashion Icon: Jean de Berry (1340-1416)

Fig. 1 - Jean de Limbourg (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). Detail of Horae ad usum Parisiensem (Le départ pour pélérinage), ca. 1412. Illumination on parchment; 21.5 x 14.5 cm. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms Latin 18014, folio 288 verso. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 2 - Limbourg brothers (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). January (detail), Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412-1416. Tempera on vellum; 22.5 x 13.6 cm (8.9 x 5.4 in). Paris: Musée Condé, Ms.65, f.1v. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 3 - Pierre Salmon (French, fl. 1368-1422). The Author Presents His Book to the King (detail), ca. 1410. Parchment. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Ms fr. 23279, fol. 53r. Source: BnF

Remembered today for his art patronage, the French prince Jean, Duke of Berry also set the standard for the sumptuous fashions of his day.

Jean de Berry was the third son of the French King Jean II and his first wife, Bonne of Luxembourg. His life was shaped by the 100 Years War between France and England. In 1356, when he was sixteen, King Jean II was taken prisoner at the Battle of Poitiers, winning his release four years later only after agreeing to send two of his sons to England as hostages. For nine years, Jean de Berry was a captive in England (Autrand 21). By the time he returned to France in 1369, his father had died, and he was charged by the new King, Charles V, with the administration of a large part of the Kingdom, from Normandy to Auvergne (Autrand 77). His political power waxed and waned under his nephew Charles VI, whose frequent attacks of mental illness after 1392 triggered struggles for power in the royal family (Autrand 121). In the clash between his nephews Louis, Duke of Orléans and Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, Jean de Berry tried to play the role of peacemaker. The 1407 assassination of the Duke of Orléans on the orders of the Duke of Burgundy, however, led him to support the Orléans or “Armagnac” faction (Autrand 125-127). As a result, the Burgundians laid siege to Jean de Berry’s properties, such as the castle of Dourdan, seen in the April calendar scene of Les Très Riches Heures, which he lost in 1411 (Pignon 13).

Throughout the year Jean de Berry travelled from castle to castle with a princely retinue, sets of tapestries, gilded table services, and his prized illuminated manuscripts (Stein). In their pages there are several portraits of him attesting to the luxury of his dress. Circa 1412, he asked Paul de Limbourg to execute a portrait of him setting out on pilgrimage (Fig. 1), to insert into an older prayer book, known as Les Petites Heures de Jean de Berry (Husband 43). This painting shows him wearing a traditional cape-sleeved robe called a houce (Van Buren and Wieck 307). His scholarly older brother Charles V had worn such robes during his reign (1364-1380) and they had contributed to his reputation as “le Sage,” (the Wise) (Scott 116). Jean de Berry’s houce appears to be made of a dark blue Italian voided velvet brocaded in red and gold and lined in fur. His accessories are a fur-trimmed barret hat (Van Buren and Wieck 295), a gilded leather belt, and a gold necklace studded with large rubies and pearls. The Duke’s posture, setting out on foot with a pilgrim’s staff, like the choice of the houce, indicate a desire to appear humble and pious, but the luxury of his attire sends a different message, asserting his royal status.

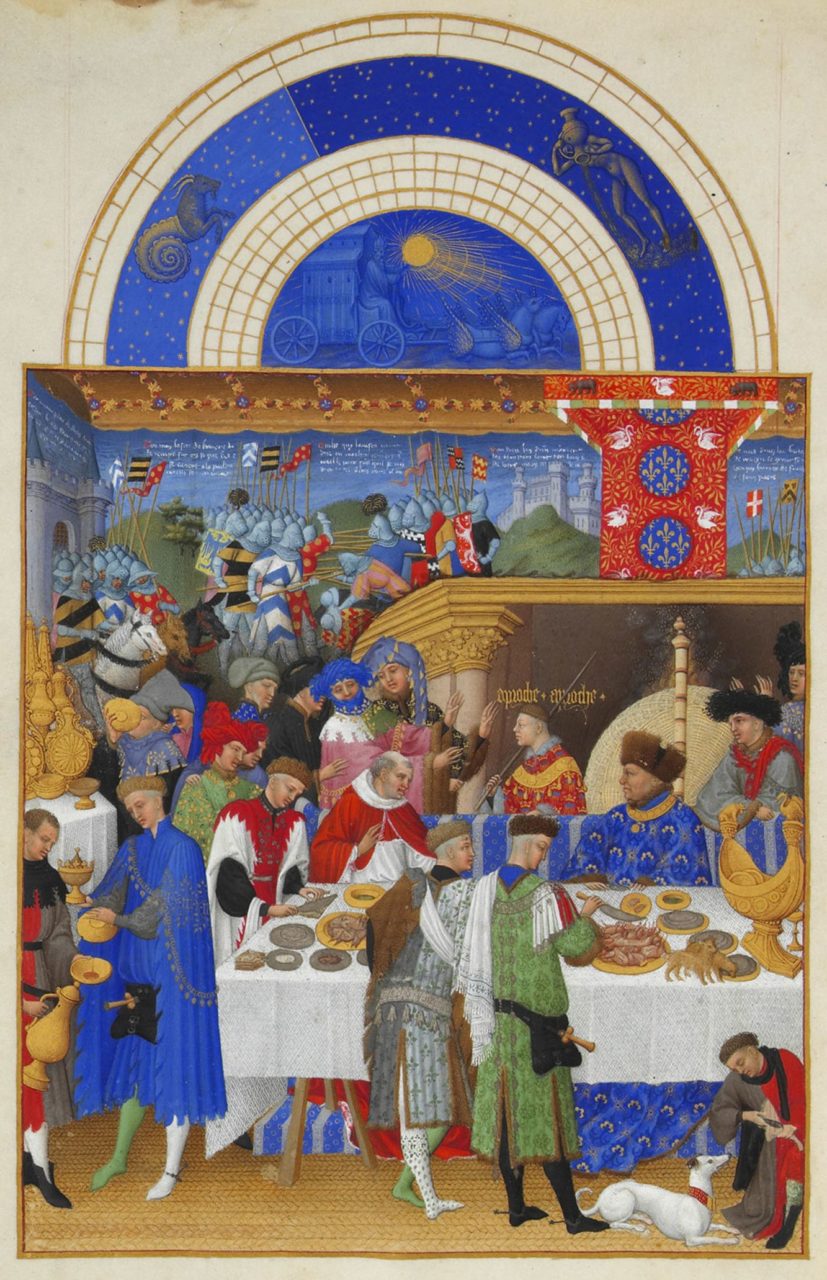

In the January calendar page in Les Très Riches Heures (Fig. 2), depicting the Duke’s New Year’s Day banquet, he wears a fur-lined houppelande of bright blue voided velvet with repeating brocaded motifs in gold that include his emblem of a radiating coronet, suggesting that the textile was custom-woven for him in Italy. His other emblems were the bear and the swan (Evans 50). Along with the French fleur-de-lys, they appear in the canopy suspended above him in this scene, and they were consistently displayed on his attire. In the illuminated manuscript of Pierre Salmon’s Dialogues which the author commissioned for Charles VI or one of the royal princes circa 1410 (Van Buren and Wieck 335), Jean de Berry is shown in conversation with Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, while the King sits on a throne in ceremonial robes of state (Fig. 3). Jean de Berry wears a long black houppelande with sweeping bombard sleeves, embroidered throughout with golden swans, that contrasts markedly with his nephew’s simpler, shorter houppelande of unpatterned cloth.

Jean de Berry’s passion for art and fashion came at a high cost. He owned jewels weighing hundreds of karats, the first piece of Chinese porcelain known to have reached Europe, and a menagerie of exotic animals (Giuffrey, Stein), but he was perennially short of money and died deeply in debt. In 1415, he anticipated a French defeat at the Battle of Agincourt and persuaded Charles VI not to join his troops, likely saving the King from death or capture (Autrand 273). The disaster of Agincourt left France with its borders diminished, its nobility decimated and its treasury empty (Van Buren and Wieck 134). Jean de Berry’s death the following year seemed to mark definitively the end of an era. Months later, the Limbourg Brothers also died, perhaps succumbing to an outbreak of plague (Gardner 410). Most of Jean the Berry’s treasures were dispersed; arguably the greatest, Les Très Riches Heures, was left unfinished and sold in a lot including tapestries and embroidered red velvet. In 1485, the book surfaced in the collection of Charles, Duke of Savoy, who commissioned Jean Colombe to complete the unfinished paintings (Autrand 247-248). It is preserved today at the Musée Condé in Chantilly, near Paris.

Menswear

Men’s fashion changed dramatically during this decade, but the basic foundation of men’s dress remained constant. In the June scene in Les Très Riches Heures (Fig. 1), one of the peasants working in the fields has stripped down to the drawers and shirt of undyed linen that all men wore under their outer clothing. The two peasants flanking him are wearing loose-fitting tunics, which they have tucked up over belts. In winter, they would wear a second tunic of wool over the first, along with woolen hose (Piponnier and Mane 87). Men of the upper classes, however had worn a different garment since the mid-1300s—the doublet, which was shorter and more fitted than the tunic. The doublet (pourpoint in French), was made of at least two layers of fabric, with padding in between the layers held in place by rows of quilting stitches. It evolved hand-in hand with plate armor as necessary padding under a knight’s heavy breastplate (Van Buren and Wieck 2). In the early 1400s the doublet remained associated with the prestige of knighthood, even when no armor was worn over it. The doublet laced down the front and had long sleeves but did not extend past the hips. It was connected to the hose by means of laces (Boucher 195). Though it was a prestigious garment and likely to be made of silk (Piponnier and Mane 68), the doublet was rarely on view during this decade, especially during its early years, when it was hidden underneath full-length houppelandes with high necklines and long flowing sleeves. In figure 2, we can catch a glimpse of Jean de Berry’s bright blue doublet and red hose, under his houce.

Fig. 1 - Limbourg brothers (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). June (detail), Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412-1416. Tempera on vellum; 22.5 x 13.6 cm (8.9 x 5.4 in). Paris: Musée Condé, Ms.65, f.6v. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2 - Jean de Limbourg (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). Detail of Horae ad usum Parisiensem (Le départ pour pélérinage), ca. 1412. Illumination on parchment; 21.5 x 14.5 cm. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms Latin 18014, folio 288 verso. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 3 - Limbourg brothers (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). April (detail), Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412-1416. Tempera on vellum; 22.5 x 13.6 cm (8.9 x 5.4 in). Paris: Musée Condé, Ms.65, f.4v. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Outer garments were the focus of men’s fashion and changed most profoundly during the decade. Les Très Riches Heures and other manuscripts show us several examples of the long houppelandes, made of the finest wools or Italian silk velvets, further decorated with gold and often incorporating personal emblems, that were worn by the men of the French royal family. The blue houppelande worn by the fiancé in the April scene (Fig. 3) has bombard sleeves lined in fur and is dagged along the edges. Dagging, which continued in fashion from the previous decade, was the decorative cutting of the edges of a garment, usually seen at hemline and sleeve edges. The sleeves of the fiancé’s houppelande are embroidered in gold with one of Jean de Berry’s emblems, the radiating coronet. In May (Fig. 4) a houppelande in similar style, made of blue voided velvet brocaded throughout in gold, is worn by the Duke’s son-in-law, the Duke of Bourbon. The entire garment, which is slit at the center back to accommodate horseback riding, is lined in golden brown fur and it is dagged at the sleeve edges. Both houppelandes are belted at a high waistline and accessorized with gold carcanets, similar those worn by women. The Duke of Bourbon displays ultra-luxurious white hose, embroidered in gold. Like his wife and her ladies, he has wound the green leaves of May around his head; his hair has been cropped short in the “bowl” cut that is well established by this decade (Van Buren and Wieck 311). The fiancé wears a chaperon, a draped headdress that took various forms depending on how it was wrapped, tied or pinned around the head. The red fabric used to make this chaperon has dagged edges, and appears to be wrapped over a bourrelet, a padded roll like those worn by women.

Fig. 4 - Limbourg brothers (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). May (detail), Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412-1416. Tempera on vellum; 22.5 x 13.6 cm (8.9 x 5.4 in). Paris: Musée Condé, Ms.65, f.5v. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 5 - Pierre Salmon (French, fl. 1368-1422). Salmon is Questioned by the King, ca. 1414. Parchment; 26.5 x 19 cm. Geneva: Bibliothèque de Genève, MS fr. 165, f. 7r. Source: e-codices

The same pairing of full-length houppelande and chaperon is worn by King Charles VI (Fig. 5), shown reclining on a bed covered in red fabric embroidered with one of his personal emblems, the broom plant; overhead on the valance of the bed hangings is his gold-embroidered motto, “Jamais,” meaning “Never,” expressing his resolve never to surrender France to the English. His black chaperon coordinates with his black voided velvet houppelande, which is brocaded throughout with the peacock feather, another royal emblem (Van Buren and Wieck 130). The bombard sleeves are lined in ermine, a fur associated with royalty and nobility for centuries (Scott 156). They reveal the sleeves of the blue and gold doublet he wears underneath. The King wears a gold belt and a pearl-studded gold necklace with pendants in the form of seedpods, designating his chivalric Order of the Broom.

Fig. 6 - Limbourg brothers (Dutch, fl. 1385-1416). January, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412-1416. Tempera on vellum; 22.5 x 13.6 cm (8.9 x 5.4 in). Paris: Musée Condé, Ms.65, f.1v. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Men’s fashion during this decade was extremely colorful. The courtier attending Jean de Berry as he departs on pilgrimage (Fig. 2), for example, wears a peach-colored chaperon, a bright blue doublet and black hose, with a mid-calf-length houppelande — a style that was called “bastard length”(Van Buren and Wieck 307) — in a lightweight pink wool or silk, lined in white. The hemline and the edges of the long bombard are heavily dagged in deep scallops, which would have emphasized every movement and gesture. The young equerries serving at the Duke’s table in the January scene (Fig. 6) demonstrate how these sleeves could be managed. The equerry in the red houppelande lined in white has pinned both sleeves up on his shoulders; the one in the parti-colored houppelande, color-blocked in contrasting shades of grey embroidered in green, has one fur-lined sleeve pinned on his shoulder. His companion in the green velvet houppelande has no need for such maneuvers, since his fur-lined sleeves are not bombards, but straight and relatively narrow. The equerry acting as the wine steward, in the bright blue houppelande, has no sleeves at all, but long panels hanging from the shoulder, dagged at the edges. The four young men display several fashion trends of the mid-decade — shorter, bastard-length houppelandes, without collars but with V-necklines in the back, low-slung belts with attached bags, and more extreme “bowl” haircuts, with most of the hair shaved except for the fluffy, curled hair at the crown.

Parti-coloring was an established practice that affected all men’s garments and accessories. Royals and aristocrats dressed their servants in parti-colored livery uniforms displaying their colors, whether heraldic or personal (Piponner and Mane 133). The Duke of Berry’s household servants seen in the January scene wear parti-colored red and gray houppelandes, with black chaperons, white hose, and black leather boots. Poulaines, shoes with extremely pointy toes, were still worn in this decade. In 1410, Charles VI was depicted wearing an embroidered pair that were so pointy that he could not have walked far in them (Van Buren and Wieck 118). Hose with attached leather soles made additional footwear optional. Two of the Duke’s equerries wear spurs for horseback riding over their soled hose. The equerry in the parti-colored houppelande also wears parti-colored hose in green and white, with the white embroidered in small green motifs.

In the January scene (Fig. 6), the walls of the Duke of Berry’s banquet hall are hung with a tapestry depicting knights in battle. The tapestry shows that knights were no less colorfully dressed, thanks to the heraldic patterned, knee-length surcôtes worn over their armor. The surcôte had developed centuries earlier to shield armor from the sun’s heat, but it also served to display a knight’s identity, through the language of heraldry, whether at a tournament or on the field of battle (Van Buren and Wieck 44-45). Under the surcôte, the knights are shown wearing solid plate armor, with chain mail gorgets protecting their necks and shoulders, and solid plate helmets with hinged visors. Chain mail, which had proved to be ineffective against the longbow, the weapon responsible for several English victories in the 1300s, had been almost completely supplanted by plate armor by the early 1400s (Evans 45) though it was still used to protect certain parts of the body (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 – Display of armor worn by knights in the early fifteenth century, combining chain mail and plate armor. Royal Armories, Agincourt 600, anniversary exhibition at the Tower of London, 2015. Photograph by Dan Kitwood, Getty Images.

Fig. 8 - Pierre Salmon (French, fl. 1368-1422). Salmon is Questioned by the King (detail), ca. 1414. Parchment; 26.5 x 19 cm. Geneva: Bibliothèque de Genève, MS fr. 165, f. 7r. Source: e-codices

At the pivotal Battle of Agincourt, in October 1415, many French knights had doubled up on their armor, wearing chain mail tunics called hauberks as well as breastplates and other pieces of plate armor (Evans 45). The English army led by the young King Henry V consisted mainly of lightly armed longbowmen and was greatly outnumbered by the French (Barker 8), but they nonetheless had the advantage on the narrow, muddy field. The longbowmen aimed for the French knights’ horses. Once knocked to the ground, weighed down by heavy armor and hampered by long surcôtes, the French sank into the mud, with some suffocating in their helmets (Barker 199-201). Although historians’ estimations of the number of dead and captured vary, the French suffered several thousand casualties and over a thousand prisoners taken for ransom, whereas English losses were in the hundreds (Barker 209-210). While other tactical errors played a part, dress and armor were certainly significant factors in the French defeat, which paved the way for the loss of Normandy and other regions of northern France to the English (Barker 254).

Agincourt also drained the French treasury, with so many aristocratic prisoners who needed to be ransomed. The defeat affected the health of King Charles VI, who became permanently insane, and it shattered the fragile truce between the Armagnac and Burgundian branches of the French royal family (Van Buren and Wieck 134). The Armagnac had taken the lead in the battle and were blamed for its disastrous outcome. The year before the battle, the Duke of Burgundy, Jean the Fearless, was nominally loyal to his cousin Charles VI and was depicted in conversation with courtiers in the King’s bedroom (Fig. 8). As compared to the King and other royal princes, Jean the Fearless is simply dressed in a “bastard-length” houppelande of green wool, with moderately full poke sleeves, a style seen in the previous decade. His matching green chaperon is also of modest proportions, like those of the men standing next to him. The only decoration is a gold-embroidered collar and belt, both alternating daisy motifs with the initials M and E, the first and last letters of the name of his wife, Marguerite of Bavaria.

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown (French). Clitipho Complains of Chremes to Menedemus; Syrus Suggests to Clitipho that he is not Chremes's Son (detail), ca. 1413. Paris: Bibliotheque de l'Arsénal, MS 664, fol. 121r. Source: BnF Gallica

Fig. 10 - Architect unknown (French). Hôtel de Bourgogne, Tour Jean sans Peur, built 1409-1411. Paris. Photo taken 21 February 2007. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The source of these simpler styles was the dress of the middle classes. Pierre Salmon, the author of this manuscript, worked as the King’s secretary and is pictured in conversation with him (Fig. 5). Salmon wears a plain gray wool houppelande with full but straight sleeves, over black hose. The strip of fabric hanging from his right knee is likely his matching chaperon, unfurled.

After Agincourt, the French court lost its appetite for long houppelandes, bombard sleeves, copious dagging, and extreme fashions in general. As Van Buren and Wieck put it, “what remained of the court …. lost all interest in fashion” (134). In illuminated manuscripts that depict middle-class city-dwellers, we see shorter houppelandes and other outer garments in plain, unpatterned wool. In figure 9, a painting from a book that had belonged to Jean de Berry, the character of Clitipho appears twice, distinguished by his pink, knee-length houppelande with straight, turned-up sleeves. His red chaperon de cou drapes around his neck and hangs partly down his back. His black chaperon echoes his black belt with its attached bag, black hose, and the black fur lining the collar and cuffs of the houppelande. The man in blue, his father Chremes, wears a huque or journade, made with two panels of cloth sewn together at the shoulders to cover the body in front and back (Van Buren and Wieck 128). The gray houppelande worn by Syrus, the man at the far right, is short enough to reveal that he wears his hose rolled over garters, exposing his knees. All the men wear short black leather boots rather than soled hose. These styles of dress would have been seen in the streets of Paris and other cities and towns in Europe.

In May of 1418, the people of Paris supported Jean the Fearless’s seizure of power in the city, where he maintained a palace. The Jean-sans-Peur Tower (Fig. 10), built 1409-1411, is all that remains of the fortified palace maintained by the Dukes of Burgundy in Paris.

Fig. 11 - Architect unknown (French). Tour Jean sans Peur (chambre de Jean sans Peur), built 1409-1411. Paris. Photo taken 26 February 2016. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown (French). Ring with a portrait of Jean Sans Peur, Duc de Bourgogne (1404-19), ca. 1410. Gold, agate?, jet, emerald, ruby; translucent enamel on gold; diameter 2.3 cm. Paris: The Louvre, OA 9524. Anonymous gift through the intermediary of the Society of Friends of the Louvre, 1951. Source: Louvre

In 2016, the Jean sans Peur Tower was the setting for the exhibition “La Mode Au Moyen Âge,” which included this reproduction of a fur-lined houppelande, chaperon de cou (resting on the shoulders like a capelet), and chaperon headdress such as Jean sans Peur might have worn (Fig. 11).

After sending the heir to the throne, the Dauphin Charles, fleeing to the south, the Duke of Burgundy now controlled the French capital and most of eastern France (Vaughan 2002, 227), while the English occupied Normandy and northern France. A supporter of Burgundian rule, or perhaps Jean the Fearless himself, wore the gold ring set with his portrait (Fig. 12). The Duke’s face is made of carved white agate, his chaperon of black jade ornamented with a ruby, and his houppelande of translucent emerald green enamel with collar of beige agate. In September 1419, his rule suddenly came to an end when he was assassinated by supporters of the Dauphin (Vaughan 2004, 1).

The decade ended with a partitioned France losing its international cultural influence to other centers of fashion. Under the new Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good (r. 1419-1467) fashion dominance would shift to Burgundy and its Flemish territories.

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Giovanni Boccaccio (Italian, 1313-1375). Decameron (detail), 1418-1419. Parchment, gold leaf; color grisaille, opaque painting; 29.5 x 22.7 cm. Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Pal. lat. 1989, fol. 320r. Source: Heidelberg Historic Literature

I nfants continued to be swaddled in this decade. Young children were dressed in loose-fitting tunics of wool over linen. As they approached the age of ten, children of the upper and middle classes were dressed more and more like adults. In the copy of Boccaccio’s Decameron illustrated in Paris circa 1418-1419 (Fig. 1), the Marquess of Saluzzo’s son wears a high-collared houppelande like his father; his sister wears a côte-hardie with a snug, fashionable cut and a hairstyle and bourrelet like her mother’s.

References:

- Autrand, Françoise. Jean de Berry: l’art et le pouvoir. Paris: Arthème Fayard, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8290775858.

- Barker, Juliet R. V. Agincourt: Henry V and the Battle That Made England. New York: Little, Brown and Co., 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/229300358.

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment. Expanded ed. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/979316852.

- Evans, Joan. Dress in Medieval France. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1952. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1008513009.

- Guiffrey, Jules. Inventaires de Jean, duc de Berry (1401-1416). Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1894. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/422256890.

- Husband, Timothy. The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/783442866.

- Piponnier, Françoise, and Perrine Mane. Dress in the Middle Ages. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/943018667.

- Pognon, Edmond, Pol de Limbourg, and Jean Colombe. Les Très riches heures du duc de Berry: 15th-century manuscript. Fribourg; Genève: Liber, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/21488446.

- Scott, Margaret. Fashion in the Middle Ages. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/777928739.

- Stein, Author: Wendy A. “Patronage of Jean de Berry (1340–1416).” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Accessed January 5, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/berr/hd_berr.htm.

- Van Buren, Anne, and Roger S. Wieck. Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands, 1325-1515. New York: The Morgan Library & Museum, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/921010074.

- Vaughan, Richard. John the Fearless: The Growth of Burgundian Power. Woodbridge [UK]: Boydell Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8290725541.

- ———. Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy. Woodbridge [UK]: Boydell Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/49942761.

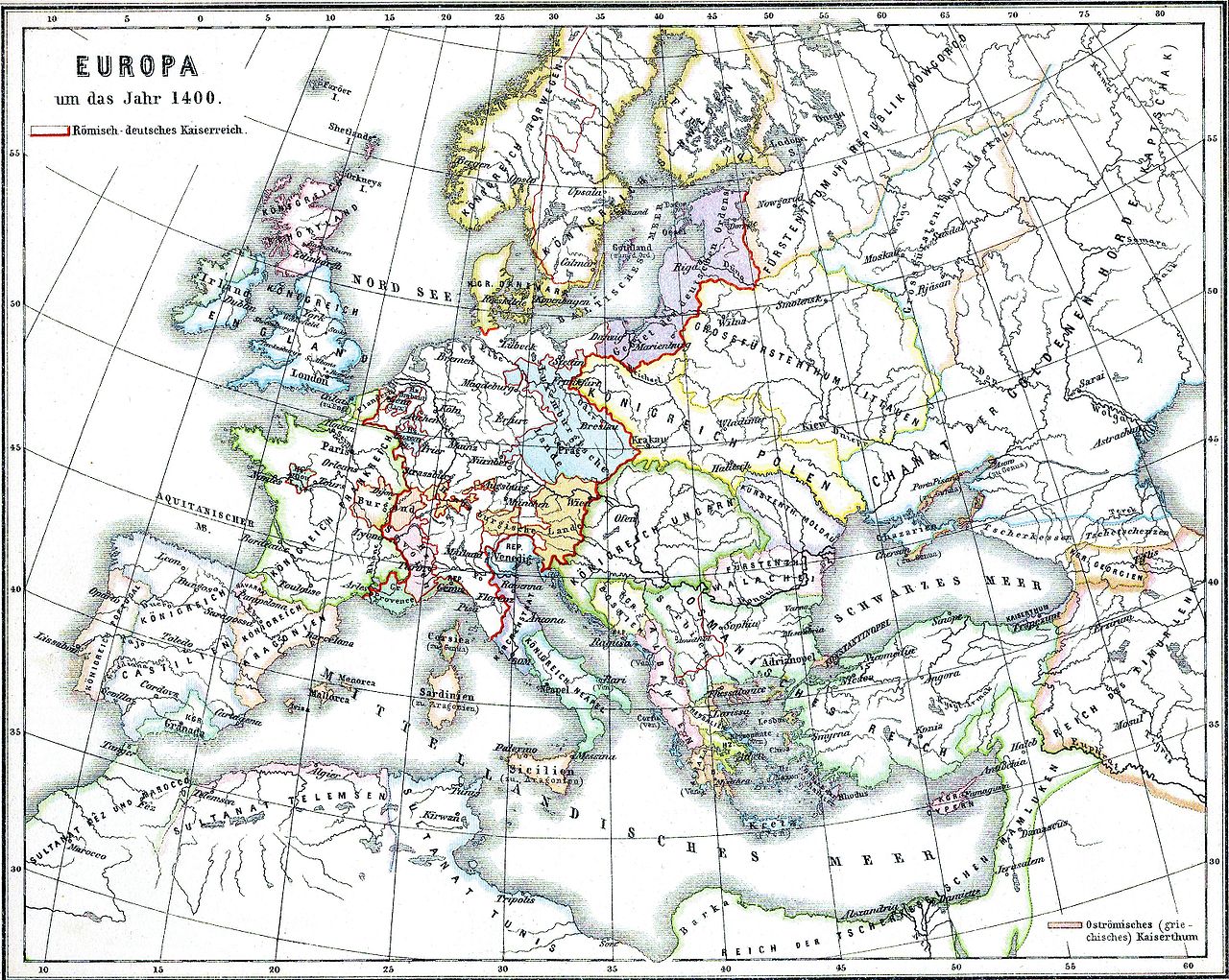

Historical Context

Europa 1400. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Events:

- 1415 – October – Battle of Agincourt

- 1415 – December – Death of the Dauphin Louis, succeeded by his younger brother Jean as heir to the French throne.

- 1416 – June – Death of Jean de Berry

- 1417 – April – Death of the Dauphin Jean, succeeded by his younger brother Charles as heir to the French throne.

- 1418 – May – Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, seizes power in Paris. The Dauphin Charles retreats south to set up a court in Bourges.

- 1419 – September – Assassination of Jean the Fearless on the orders of the Dauphin.

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 15th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.