OVERVIEW

Rococo fashion was all the rage in the 1740s along with the robe à la française worn as the primary gown for both formal and informal occasions. At the same time, men’s fashion remained just as full as the 1730s, and French and English fashion represented two ends of a spectrum.

The middle decades of the eighteenth century constitute what dress historian Aileen Ribeiro characterizes as “the triumph of the rococo” (Ribeiro 121). The robe à la française with its characteristic back pleats falling from shoulders to hem was worn throughout Europe, as both formal and informal dress. The most notable change in the gown from its introduction around 1720 was the tighter-fitting bodice that was cut separately from the skirt, oval sleeve ruffles that replaced the wing cuffs of the previous decades, and the addition of applied decoration, often in the form self-fabric, silk flowers, and delicate passementerie that was stitched down the center-front opening and across the front of the petticoat. Hoops, or paniers, were at their widest in this decade, especially when worn at court in England. Men’s coats retained the fullness of the previous decade with prominent sleeve cuffs and flared skirts, and the already established contrast between English understatement and French luxury is evident in contemporary portraiture.

Womenswear

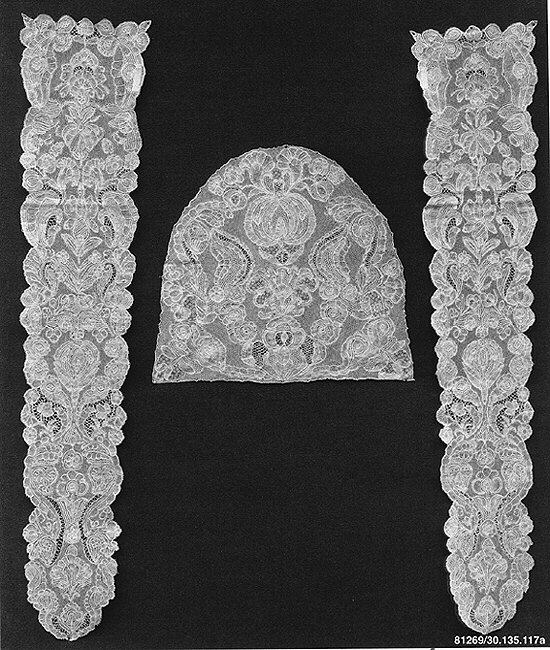

Charles Antoine Coypel’s 1743 pastel portrait of François de Jullienne and his wife, Marie Elisabeth de Séré de Rieux, conveys the grace and elegance associated with male and female clothing during this decade (Fig. 1). Madame de Jullienne, who holds a knotting shuttle, wears an ivory silk satin robe à la française whose plainness sets off her rich accessories (Figs. 2-3). Gathered bands of lace are stitched to her stomacher and bands of metallic bobbin lace almost cover the pleats of her bodice front and embellish the edges of her wing sleeve cuffs. Her black silk lace “necklace” is caught with oval-shaped diamond brooches; and a floral-and-pearl ornament, called a pompon, and a small lace cap with long lappets decorate her delicately powdered hair. Tied with pink silk ribbons matching those at her elbows, the lappets are en suite with her double engageantes, or sleeve ruffles. Coypel has depicted in meticulous detail the flower petals with their raised outlines and the hexagonal mesh ground of her Brussels bobbin lace accessories that stand out against the sheen of the blue-green silk covering the small table to her left (Figs. 1, 4). Madame de Jullienne’s additional jewelry comprises diamond drop earrings and a pearl bracelet set with diamonds and a pink stone. This lavish ensemble was presumably made possible by her equally well-attired husband’s generous purse—his father was “a wealthy textile merchant, collector of paintings, and a patron of Antoine Watteau” (The Met).

Fig. 1 - Charles Antoine Coypel (French, c. 1694–1752). François de Jullienne (1722–1754) and his wife Marie Élisabeth de Jullienne (Marie Élisabeth de Séré de Rieux, 1724–1795), ca. 1743. Oil on canvas; 100 x 80 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.84. Purchase, Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, in honor of Annette de la Renta, 2011. Source: The Met

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (European). Woman's dress and Petticoat (Robe à la française), ca. 1745. Silk plain weave (shot taffeta). Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2007.211.927a-b. Source: LACMA

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (European). Back View of Woman's dress and Petticoat (Robe à la française), ca. 1745. Silk plain weave (shot taffeta). Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2007.211.927a-b. Source: LACMA

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (Flemish). Cap crown and pair of lappets, ca. 1720-1740. Bobbin lace. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.135.117a–c. Gift of Mrs. Edward S. Harkness, 1930. Source: The Met

Fig. 5 - François Boucher (French, c. 1703-1770). La Toilette, ca. 1742. Oil on canvas; 52.5 x 66.5 cm. Madrid: Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum, 58 (1967.4). Source: TBMN

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown. Pair of Shoes, ca. 1740-1750. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.449-1913. Given by Messrs Harrods Ltd.. Source: V&A

François Boucher’s La Toilette (Fig. 5) offers a provocative view of an attractive young woman getting ready for the day, attended by her maidservant who holds out a cap for her approval. Seated close to a fireplace in an elegantly appointed, if slightly disheveled, domestic interior, she wears a white linen sleeved combing jacket, or peignoir, to protect her clothes from cosmetics (applied liberally applied to her face), hair powder and pomatum. Visible under the front opening of the combing jacket are her partially laced corset and the top ruffle of her linen chemise, the primary female undergarments. To secure her pale grey silk clocked stocking with a pink silk ribbon, she has lifted the petticoat of her blue silk gown over her knee, revealing both her white underpetticoat and the suggestively placed kitten playing with a ball of wool. Her maidservant wears a white silk robe à la française with the front corners of the hem tucked up into her petticoat pockets in a style known as retroussée dans les poches over a green silk petticoat. Their close-to-the-head curled coiffures worn with small beribboned caps and high-heeled mules (Fig. 6), primarily worn indoors, are the epitome of feminine fashion during this decade.

Although English women wore the open robe à la française, known as a sack, they often preferred all-in-one gowns, with the petticoat integral to the dress and its top edge concealed at the front by a stomacher (Fig. 7). In William Hogarth’s 1742 portrait of Mary Edwards (Fig. 8)—an heiress and loyal patron of the artist—the sitter wears “an English version of the French sack back gown” with “a closed skirt, rather than an open overskirt worn with a matching petticoat” (Chrisman 7-8).

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (British). Stomacher, ca. 1740-1760. Silk, linen, silver; hand-woven, hand-embroidered. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.186-1959. Given by Mrs O. L. Meyrick-Jones. Source: V&A

Fig. 8 - William Hogarth (British, c. 1697-1764). Miss Mary Edwards, ca. 1742. Oil on canvas; 126.4 × 101.3 cm. New York: The Frick Collection, 1914.1.75. Henry Clay Frick Bequest. Source: The Frick Collection

Fig. 9 - Anna Maria Garthwaite (English, c. 1688-1763). Banyan, 1740-1750 (woven), 1750-1760 (made). Silk, linen, hand-woven damask, hand-sewn. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.92-2003. Purchased with Art Fund support and assistance from the Friends of the V&A, and a number of private donors. Source: V&A

Fig. 10 - Hubert-François Gravelot (French, c. 1699-1773). Le Lecteur, ca. 1725-1750. Oil on canvas. Richmond: English Heritage, Marble Hill House, 88029317. purchased with the assistance of the Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund, 1968. Source: Art UK

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (British). Quilted Petticoat, ca. 1730-1770. Silk, wool; hand-woven, hand-quilted, handsewn. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.427-1966. Given by J. B. Fowler, Esq.. Source: V&A

Dress historian Kimberly Chrisman notes that although Edwards’s gown “is French in origin, the [large-scale] silk design is typical of English damasks of the period” and that her choice of this particular fabric “emphasizes the staunchly English character of the sitter” (Chrisman 8). A woman’s green silk dressing gown dating about 1740-1750 (Fig. 9) shows the impressive long repeats of these monochromatic textiles that depended on the reflection of light to appreciate fully their contrasting satin-and-plain weave surfaces. Like Madame de Jullienne, Mary Edwards has accessorized her gown with lace and jewelry. Although her cap, lappets, kerchief, and sleeve ruffles of expensive Brussels bobbin lace compliment her untrimmed red damask gown, she “wears a quantity of jewellery rarely seen in English portraiture, except for ceremonial or court dress” including “a parure of matching brilliant-cut diamonds together with a pearl necklace… gold rings, chatelaine, and watch” (Chrisman 8). Highly independent and enormously wealthy, Edwards was perceived as somewhat eccentric (Chrisman 1).

Gowns with fitted backs were also popular in England. In Hubert Gravelot’s painting of a young man reading to his female companion (Fig. 10), the attentive listener wears what was known as a “nightgown.” According to dress historian Anne Buck, “originally it probably did not reveal the petticoat;” later, however, “the front opening widened to reveal the petticoat” (Buck 43). As she also notes, although these gowns were often worn with matching petticoats, those that survive without this accompanying garment may well have been worn with a contrasting petticoat. In Gravelot’s quiet interior scene, the young woman wears a quilted pink silk petticoat with her oyster-white silk gown and a sheer white cotton apron. Quilted petticoats (Fig. 11) were much more widely worn in England than in France and they appear often in portraits and genre scenes, like this one. The informality and practicality of the nightgown were “emphasized by its being worn without hoops or very small ones, and with an apron” (Buck 43). In 1740, Lady Hartford wrote of her partiality to aprons when she was at home and that she could “not endure a hoop that would overturn all the chairs and stools in my closet” (quoted in Buck 43).

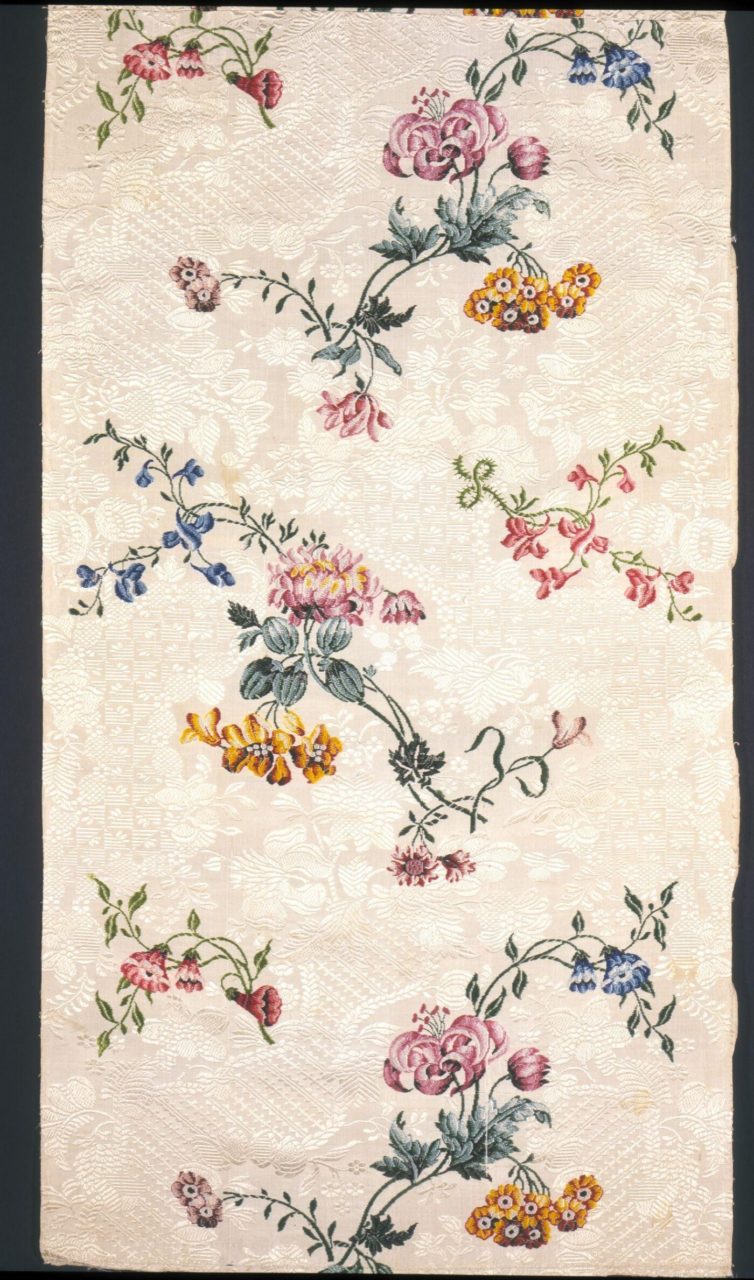

In contrast to single-color damasks with extended repeats, the floral-and-foliate motifs in English brocaded silks of this decade were considerably more restrained in size. Textile historian Natalie Rothstein describes the shift that occurred in 1742 as marking “both the culmination of this [1730s] style and its eclipse” (47). Not only lighter in weight by virtue of their grounds with less complicated weave structures such as taffeta, Spitalfields silks “were the harbingers of a totally new naturalism” with identifiable flowers including “carnations, apple blossoms, roses…carnations, [and] lilies of the valley” (Rothstein 47). Rothstein observes that the “essence of the English interpretation of Rococo in silk design [1743-1753] was an accurate rendering of botanical detail with flowers casually scattered across an open ground” (Rothstein 47), as seen in brocaded silks by Anna Maria Garthwaite (Figs. 12, 13), the only woman among the few known eighteenth-century Spitalfields designers (Rothstein 47).

A closed robe with its rare surviving matching shoes is made of a brocaded silk taffeta dating about 1742-1744, possibly by Garthwaite (Fig. 14). The design “features stylized primroses commingled with blackberries…sprouting curling elements known botanically as ‘styles,’ and hops” (De Gregorio 15). Flowers and fruits were commonly used motifs for woven silks throughout the century, but the inclusion of hops is highly unusual, although they “would have been familiar to Garthwaite… who shared streets with breweries as well as flower stalls” (De Gregorio 15). The gown was remade, probably from a mantua, within about a decade after the textile was woven. These kinds of alterations occurred regularly during the period, a few years or even decades later, due to the great expense and inherent value of silks, especially those with elaborately brocaded patterns.

Fig. 12 - Anna Maria Garthwaite (English, c. 1688-1763). Gown, ca. 1740s. Brocaded satin in coloured silks. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.264-1966. Given by Mrs Olive Furnivall. Source: V&A

Fig. 13 - Anna Maria Garthwaite (English, c. 1688-1763). Dress Fabric, ca. 1749. Dress fabric, brocaded silk. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.192-1996. Source: V&A

Fig. 14 - Possibly Anna Maria Garthwaite (English, c. 1688-1763). Round Gown of Brocaded Silk, ca. 1750-1760. English brocaded silk. Source: Cora Ginsburg

Fig. 15 - Designer unknown (Dutch). Woman’s dress (Robe à la française), ca. 1740-1760. Silk satin with silk and metallic-thread supplementary weft-float patterning. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2007.211.928. Source: LACMA

Fig. 16 - Designer unknown (Dutch). Fabric from a Woman’s dress (Robe à la française), ca. 1740-1760. Silk satin with silk and metallic-thread supplementary weft-float patterning. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2007.211.928. Source: LACMA

Chinoiserie silks were also in vogue during the 1740s. A brocaded satin robe à la française (Figs. 15, 16) with the newly fashionable oval sleeve cuffs combines familiar floral-and-foliate motifs with whimsical diminutive pagoda-like structures, seated figures in tall, pointed hats, and fantastical birds. A highly unusual robe à la française (Fig. 17) is hand-painted on a silk moiré ground with large-scale exotic and stylized blooms and serrated leaves on undulating stems “that transform its wearer into a floating garden” (Stewart 83). The gown also illustrates the type of rich trimmings that (in addition to self-fabric) characterize formal dresses of the third quarter of the eighteenth century. Here, “a passementerie lattice of crocheted netting ivory silk” net (Fig. 18) dotted with silk fly-fringe flowers decorates the front edges and a profusion of flowers and fly-fringe adorns the oval sleeve cuffs (Fig. 19) (Stewart 83).

By the 1730s in England, the mantua that had started out as a loose-fitting informal garment in the 1670s had become formalized with a tight-fitting bodice and a long narrow train looped up behind.

Fig. 17 - Designer unknown (Dutch or German). Robe à la Française, ca. 1740s. Silk, pigment, linen. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995.235a, b. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1995. Source: The Met

Fig. 18 - Designer unknown (Dutch or Germsn). Detail of a Robe à la Française, ca. 1740s. Silk, pigment, linen. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995.235a, b. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1995. Source: The Met

Fig. 19 - Designer unknown (Dutch or German). Detail of a Robe à la Française, ca. 1740s. Silk, pigment, linen. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995.235a, b. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1995. Source: The Met

Fig. 20 - Designer unknown (English). Mantua, ca. 1740-1745. Silk, linen, silk thread, linen thread. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.227&A, B-1970. Given by Lord and Lady Cowdray. Source: V&A

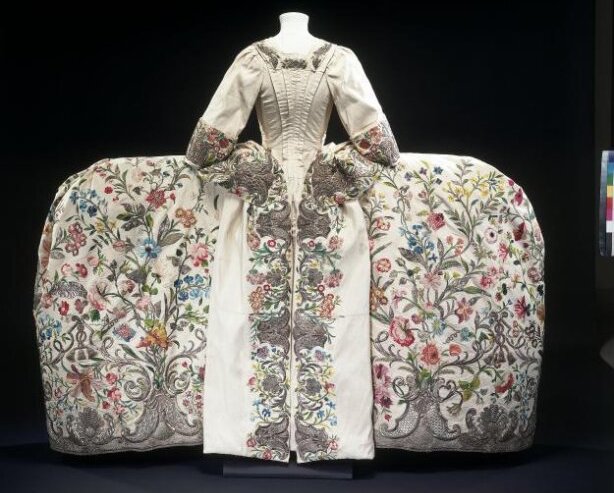

According to dress historian Madeleine Ginsburg, a mantua dating to the late 1740s in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum (Fig. 20) “is the most sumptuous piece of costume embroidery known to have survived… and unique in bearing the signature of one of its embroideresses” (Ginsburg 151). Spread across the front and back of the four-and-a-half-foot wide skirt are serpentine stems with large-scale stylized flowers that “recall the mixture of oriental and western motifs on Indian chintz hangings” of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, while the border “also looks back to older, more formal styles” (Ginsburg 151). The enormous cost involved in embroidering this expanse of fabric was compounded by the wearer’s change of mind—areas of colored silks on the back later oversewn with silver thread indicate that the gown originally was to be multicolored (Ginsburg 151). Ginsburg notes that the inscription on the reverse of the train, “Received of Mdme Lecompte by me Magd Giles,” may “have referred to the handing over of a large amount, approximately ten pounds, of expensive silver wire in several textures, plated, spangles and twist, or to the subcontracting of a very large complicated piece of work” (Ginsburg 151). The finished gown weighs a substantial 15 pounds.

Fig. 21 - Designer unknown (English). Mantua, ca. 1740-1745. Embroidered silk with coloured silk and silver thread. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.260&A-1969. Source: V&A

Fig. 22 - Designer unknown (English). Back View of a Mantua, ca. 1740-1745. Embroidered silk with coloured silk and silver thread. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.260&A-1969. Source: V&A

Another opulent mantua (Figs. 21, 22), worked in both silk and metal threads and worn by Isabella Courtenay for her wedding on May 14, 1744, incorporates the more-up-to-date naturalistic flowers and shell motifs typical of rococo ornament (Ginsburg 152).

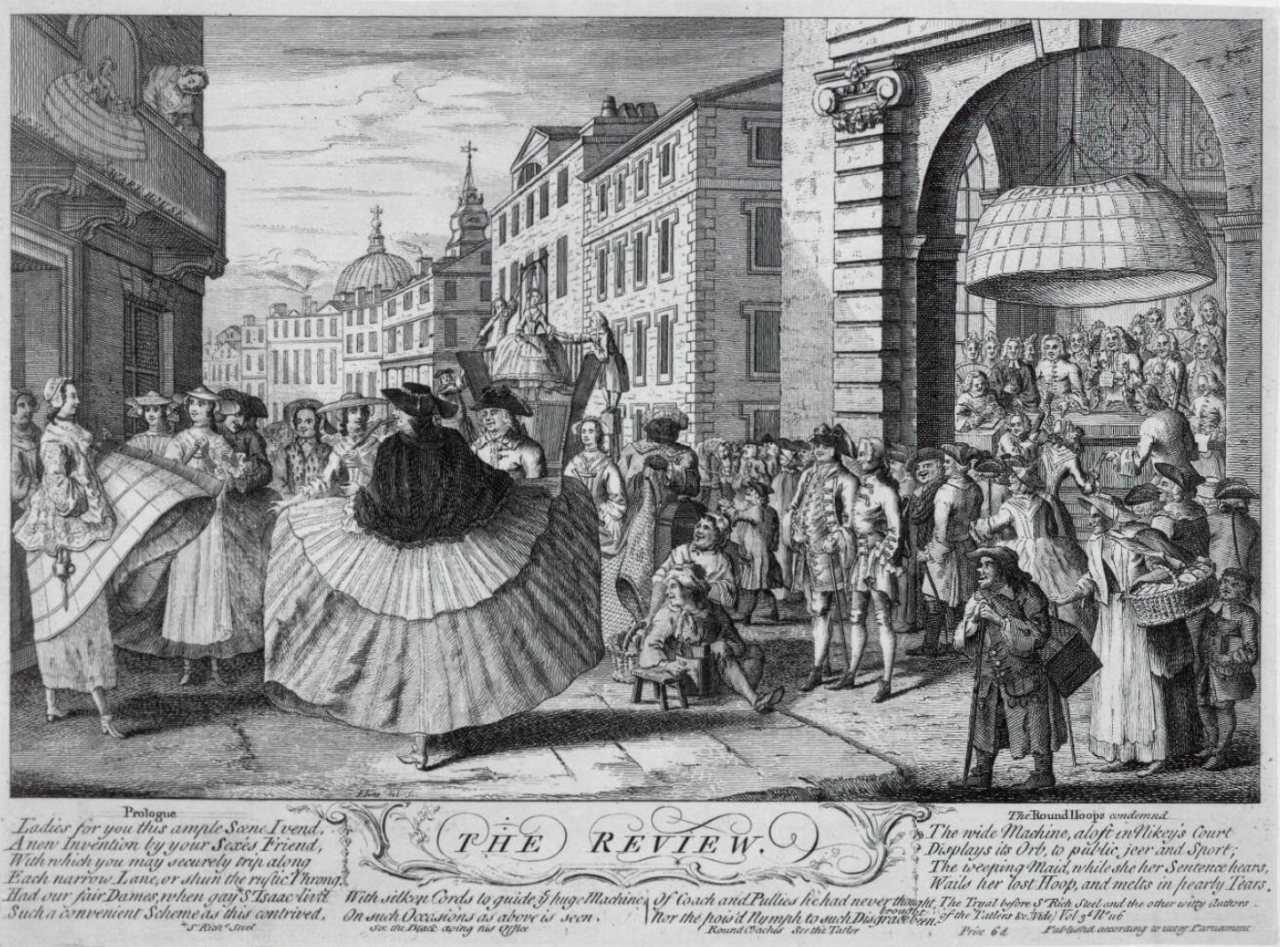

Although wide hoops were worn on both sides of the Channel, their rigid squared-off shape was distinctive to England (Figs. 20-24). A 1748 caricature mocks the extravagant proportions of the hoop that—to the consternation of critics—grew ever larger and women firmly refused to give up (Fig. 25). In the foreground, a woman in a spreading hoop prepares to make her way down a crowded street. In the distance, another woman attached to a pulley is being lowered into her carriage through the open roof by two men. At the right, a large, suspended hoop serves as a dome for the men and women gathered underneath in consultation; and on the left, a young woman collapses her hoop—the better to enter the fray. Above the doorway of the building identified as a “warehouse” is a hoop-attired ornamental figure that suggests the woman’s hoop is a recent purchase.

Fig. 23 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, c. 1727-1788). Conversation in a Park, ca. 1740. Oil on canvas; 73 x 68 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre. Source: WGA

Fig. 24 - Arthur Devis (British, c. 1712-1787). Alicia Maria Carpenter, Countess of Egremont, ca. 1745. Oil on canvas; 61.3 x 42.2 cm. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1940.10. Mildred Anna Williams Collection. Source: FAMSF

Fig. 25 - John June (British). Satire on Female Fashion, ca. 1748. Engraving. London: The British Museum, 1871,1209.2822. Source: British Museum

Fig. 26 - Louis Tocqué (French, c. 1696-1772). Portrait of Marie Leszczyńska (1703-1768), Queen of France, ca. 1740. Oil on canvas. Paris: Musée du Louvre, INV. 8177. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 27 - Artist unknown (English). Page from Barbara Johnson's Album, ca. 1746-1823. Paper, parchment, textiles. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.219-1973. Source: V&A

In France, the long-fossilized grand habit remained obligatory court attire for women. In 1740, Louis Tocqué painted Queen Maria Leszynska in this three-piece ensemble comprising a heavily boned bodice, petticoat, and long train (Fig. 26). The brocaded silk with swirling polychrome flowers and scrolling gold bands is undoubtedly a product of Lyon, which had been the center of the silk weaving industry since the reign of Louis XIV. These renowned luxury commodities were sought after by affluent consumers and copied by weavers throughout Europe. In addition to the (undoubtedly French) lace tour de gorge and tiered, gathered sleeve ruffles and gold bobbin lace, the queen wears diamonds in her hair and a spectacular diamond-and-pearl stomacher brooch surrounded by gold bobbin lace. Diamond clasps secure her blue velvet ermine-lined mantle embroidered with large gold fleur-de-lys, and all of these reflective surfaces would have sparkled in candlelight.

In addition to plain silks, such as taffetas, that women might use for everyday dress, printed fabrics of cotton-and-linen mixture (with linen warps and cotton wefts) and linen were also available, particularly in England, where the bans against these textiles were less stringent than in France. Barbara Johnson (1738-1825), daughter of a clergyman from Olney, Buckinghamshire, kept a wardrobe diary between 1746 and 1823 that charts both her fabric preferences and changing fashions in textiles over this seventy-year span (see Timeline 1750s; 1770s; 1780s). A page from her album (Fig. 27) includes swatches of silks, cottons, and linen purchased from 1746 to 1749 to make up “a flower’d Calicoe [block-printed floral cotton] long sack;” “a Blue damask Coat [petticoat];” “a flower’d Cotton Jacket;” “a blue & white linnen long sack;” “a flower’d silk Robe-Coat [gown and petticoat];” and “a green Camblet [wool or wool-and-silk mixture) Coat” (Rothstein/Barbara Johnson’s Album of Styles and Fabrics, n. p.).

As her album confirms, Johnson wore sacks of silk, cotton, and linen, probably for a variety of occasions; her cotton jacket, however, would have been for informal wear.

Printed cottons were also within the purchasing power of working-class people. As historian of consumption John Styles states, “cotton was the fiber of industrial revolution,” processed “in “the new factories powered by water or steam that multiplied from the 1770s [and] housed machines invented specifically” for that purpose (Styles 109). In 1774, the Acts established in the early eighteenth century that prohibited “the wearing of pure cotton” were repealed, enabling “printing to be undertaken legally on fabric with a cotton warp and weft” (Styles 127).

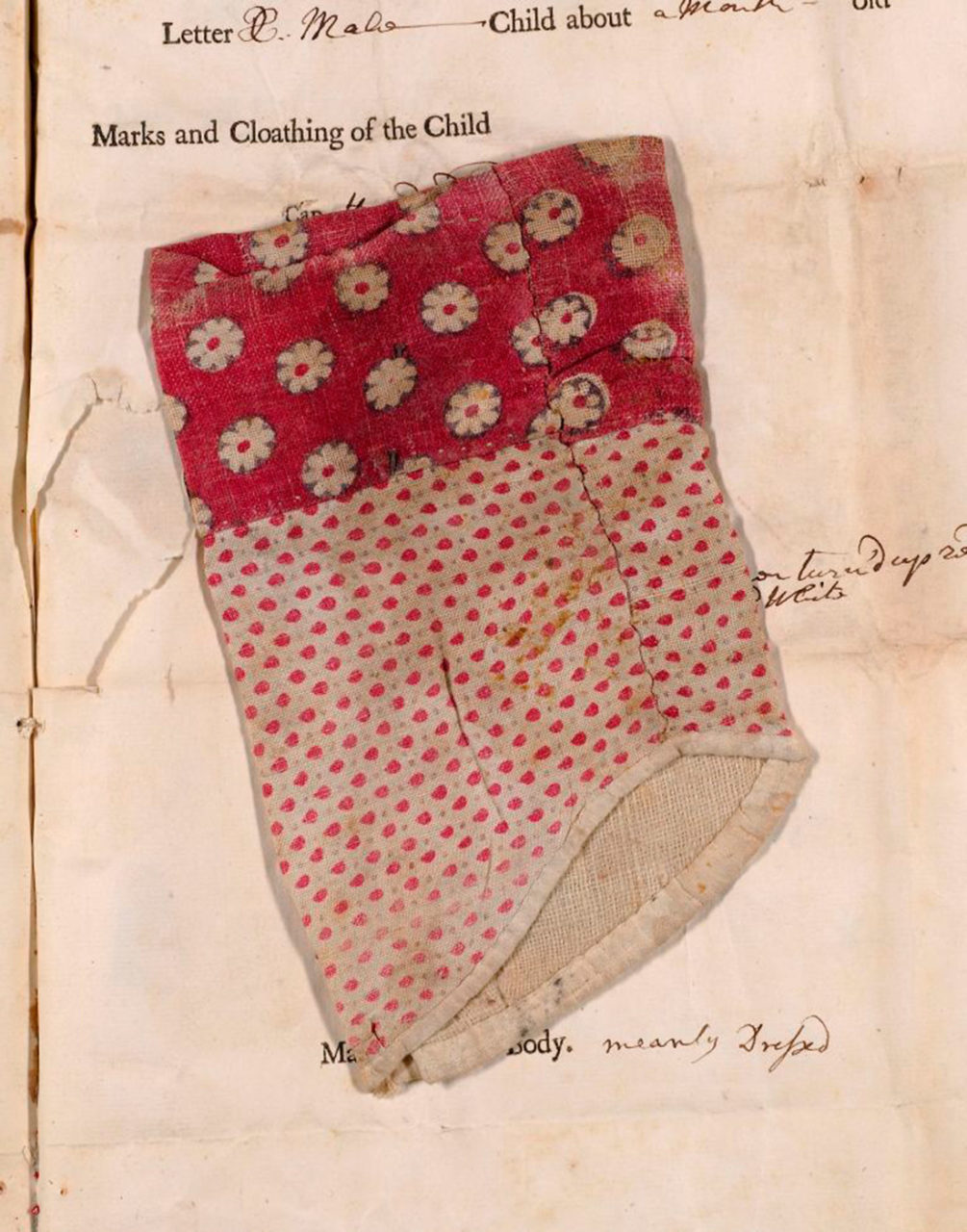

Fig. 28 - Designer unknown. Sleeve from London Foundling Hospital Billet Books, ca. 1746. Sleeves red and white speckl’d linen turn’d up red spotted with white. London: The Foundling Museum. Source: Foundling Museum

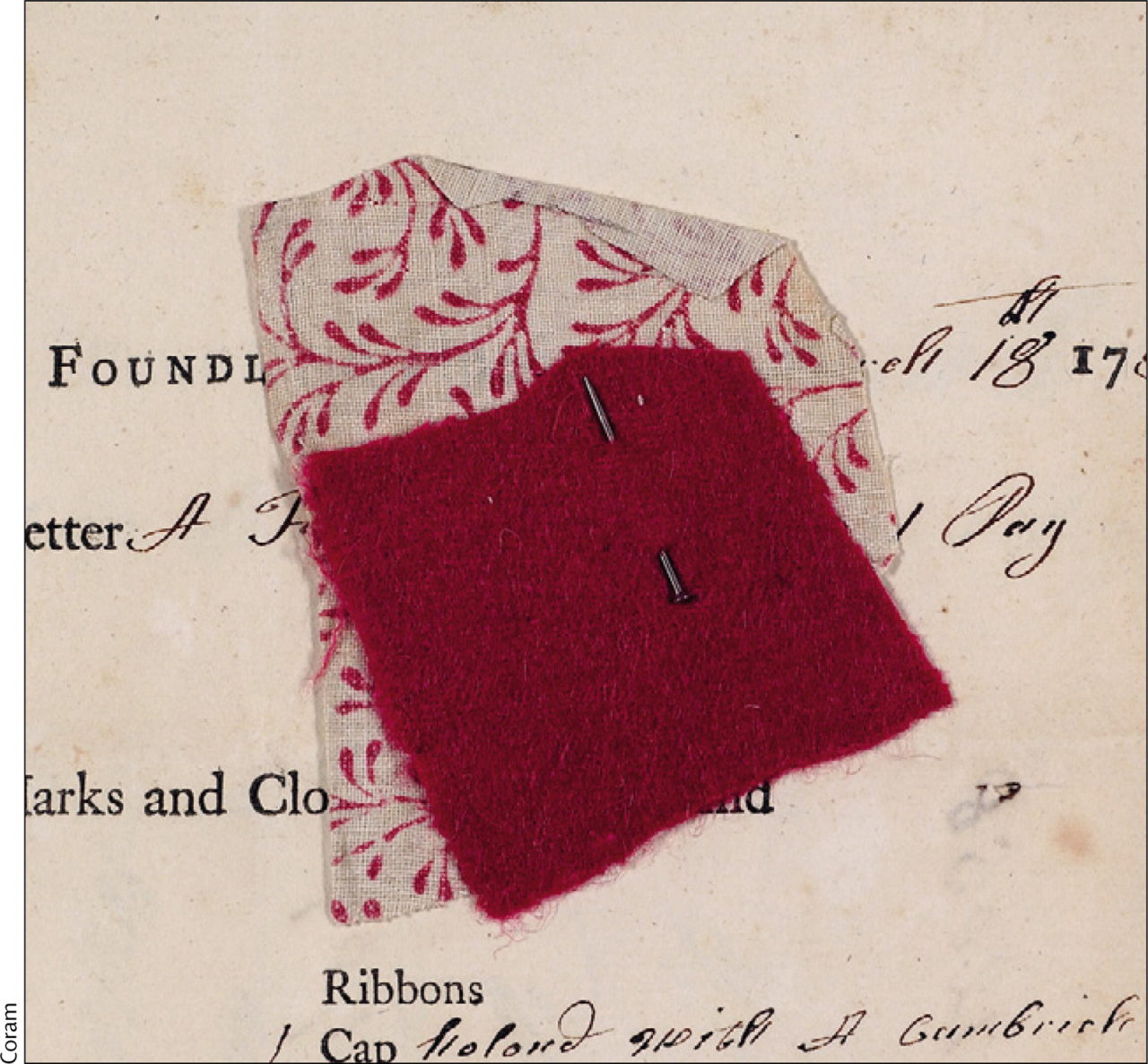

Fig. 29 - Designer unknown. Textile from London Foundling Hospital Billet Books, ca. 1758. London: The Foundling Museum. Source: Lancet

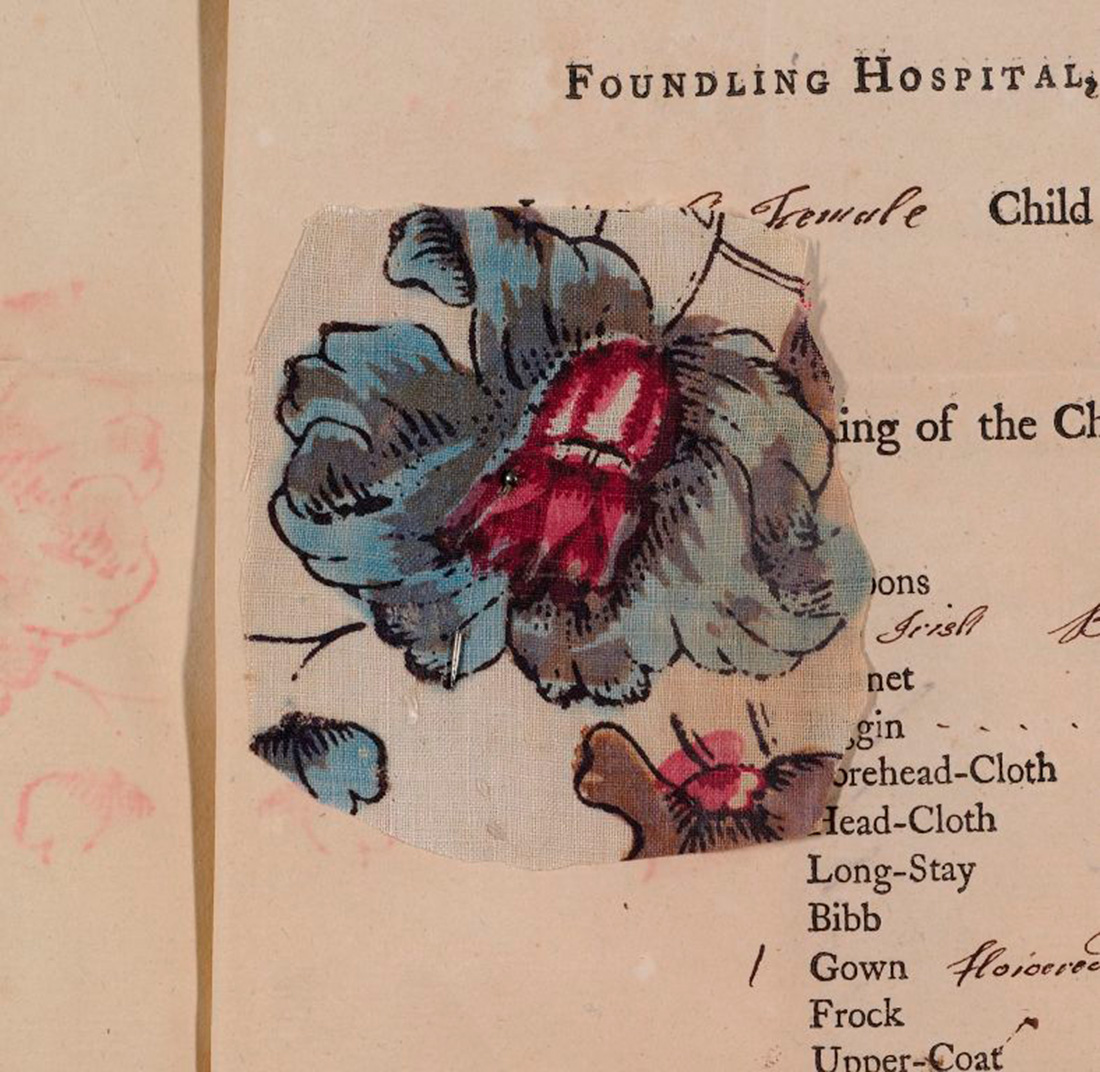

Fig. 30 - Designer unknown. Textile from London Foundling Hospital Billet Books, ca. 1759. Lawn printed with flowers. London: The Foundling Museum. Source: Foundling Museum

In 1769, Richard Arkwright was granted a patent for the power-driven spinning frame that allowed for the manufacture of cotton threads strong enough to be used for the warp. Although expensive, hand-painted-and-dyed Indian cottons satisfied the desire for sartorial exclusivity among the wealthy, English manufacturers produced more affordable cotton-and-linen mixtures and linens that targeted plebian consumers, who appreciated them for their washability, fashion, and price (Styles 114).

In his exhaustive study of clothing worn by ordinary English men and women in the eighteenth century, Styles examined criminal records, inventories, diaries, and other documentary evidence, including the large collection of cotton and linen swatches in the London Foundling Hospital billet books (Figs. 28-30), dating from 1741 to 1760 that provide “an unparalleled archive of what ordinary women wore” (Styles 114). As he points out, although these printed textiles reflect current design trends, the frequent use of one or two colors and “the coarseness of the yarn, the density of the weave and the register of the printing” made them cheaper to produce and more attractive to those of lesser means, especially when compared with the alternatives of low-end wool and wool-and-silk mixtures (Styles 116, 118). However, as Styles notes, the success that cotton enjoyed as a dress fabric among women of the middling and working classes “resulted…from its superior appearance, not its cheapness” (Styles 127).

SECOND-HAND AND READY-MADE CLOTHING

Throughout the eighteenth century, men and women—including those of the working classes—had their clothes custom made. However, the thriving second-hand market and warehouses that sold ready-made garments and accessories were important sources for those of lesser means. From the beginning of the century, men could buy suits and loose-fitting gowns, while for women, day and at-home gowns and accessories were available. In 1747, R. Campbell, author of The London Tradesman, identified the second-hand industry:

“The Salesmen [or saleswomen] deal in Old Cloaths, and sometimes in New. They trade very largely, and some are worth some Thousands: they are mostly Taylors, at least, must have a perfect Skill in that Craft. I do not know [if] they take Apprentices as Salesmen, but they keep Journeymen, to whom they give common Taylor’s Wages.” (quoted in Lemire 70)

In her examination of this sector of the clothing market in eighteenth-century England, historian Beverly Lemire explains that “the second-hand trade in clothes flourished as one of the most common commercial transactions of the pre-industrial and early industrial period” and that by “[channeling] garments of fashion and utility through the largest segment of the population, [it] helped stimulate a greater industrial productivity and involved the majority of the population as sellers and buyers” (Lemire 67). The desire for and easy access to second-hand clothing in both large urban centers and smaller towns made it possible for those of the middle and laboring classes to purchase current fashions at reduced prices (Lemire 67).

However, the recycling of garments that started at the top caused consternation among those who adhered to the notion that one’s socio-economic status should be communicated by appropriate dress. In 1754, a commentator groused about the “tawdry Gentility of a Tallow-chandler’s Daughter… the aukward Pride of Dress in a Butcher’s Wife [and] numerous Fraternity of the Shabby-genteel” who wore altered, second-hand coats and waistcoats (quoted in Lemire 80). In spite of such complaints made continuously throughout the century, the second-hand clothing trade “developed new patterns of consumerism and bolstered the spread of popular fashions” (Lemire 80).

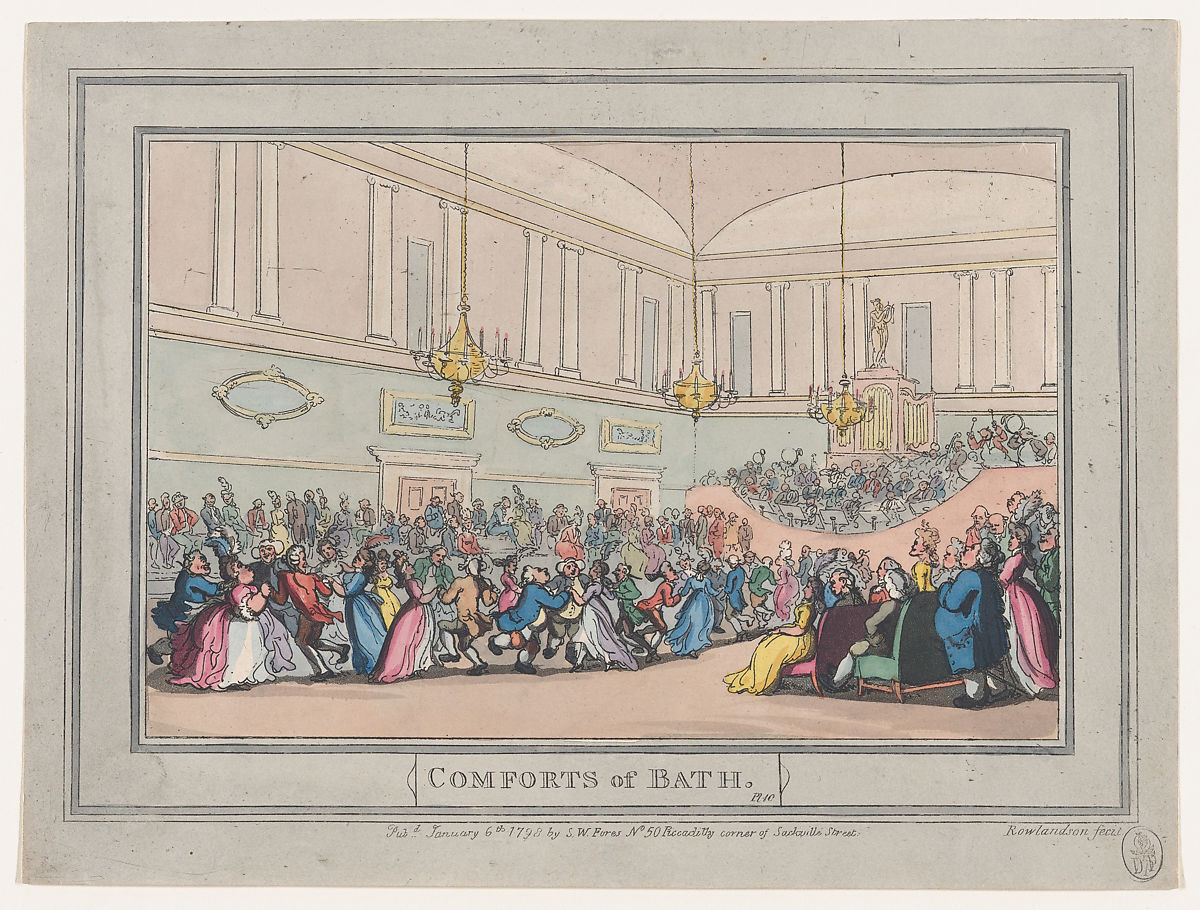

Fig. 31 - Thomas Rowlandson (British, c. 1757-1827). Comforts of Bath, Plate 10, January 6, 1798. Hand-colored etching and aquatint; 19.6 × 26 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 59.533.558(10). The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959. Source: The Met

Beginning in the 1730s in London, the term “warehouse” (Fig. 25) referred to “any large shop that sold commodities cheaply and in quantity—especially fabrics, articles of ready-made clothing, personal accessories, fancy goods, [and] household wares” (Fawcett 32). Although a warehouse might sometimes be the “sales outlet for a single manufacturer,” it generally “served as agent and distributor for a variety of suppliers, retailing directly and also wholesaling to other tradesmen in its area” (Fawcett 32). Like today’s department stores, these retailing establishments depended on a rapid turnover of stock, “which in turn meant regular replenishment, moderate pricing… active sales promotion, and a standard rather than exclusive range of goods” (Fawcett). Additionally, while affluent consumers were usually extended credit by their fabric merchants, tailors, and dressmakers (the more affluent the customer, the more credit he or she generally received), those shopping at warehouses paid cash.

The spa city of Bath (Fig. 31) attracted many visitors who sought to cure their various ills by drinking or submerging themselves in the mineral waters as well as those who wanted to enjoy the numerous leisure activities it offered—including shopping—and the surrounding scenic beauty. Retail warehouses were a fixture of Bath from the 1740s. In 1744, the firm of Francis Bennett & Co. that dealt in linen and woolens used the term “when they referred to [their] main warehouse in Abbey Churchyard and to ‘their several other Ware-Houses in Bath’” (quoted in Fawcett 32). In this notice that appeared in the Bath Journal on both June 4 and October 4, the drapers also indicated that their policy was to sell at the lowest prices possible and to accept only “ready money” (quoted in Fawcett 32). In 1748, Elizabeth Chancellor, a lace dealer with a warehouse in London, placed an advertisement in the Bath Journal notifying customers that she received weekly consignments from her establishment in the capital at her recently opened premises in Bath (Fawcett 32).

Fashion Icon: PAMELA, or Virtue Rewarded (1740)

In November 1740, Samuel Richardson published his eponymous, epistolary novel, Pamela, or, Virtue Rewarded, that was both a literary success and a commercial triumph. One of the first novels to be published in England, Richardson’s tale is of a beautiful young servant girl who is aggressively pursued by the son of her late mistress and consistently refuses his advances until he agrees to marry her (Figs. 1-5). The first five editions were published in less than a year, attesting to the novel’s enormous popularity (Keymer and Sabor 20). In addition to these multiple authorized editions and Richardson’s 1741 sequel, Pamela in Her Exalted Condition, there were “piracies of several kinds including abridgments, newspaper serializations and Dublin editions,” as well as Henry Fielding’s satirical response, An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews in which the many notorious Falshehoods and Misrepresentations of a Book called Pamela are exposed and refuted, also published in 1741 (Keymer and Sabor 20).

The Pamela phenomenon included paintings and prints, ephemeral merchandise, waxworks, and racehorses named for this virtuous young maiden. In late 1741 and early 1742, while the artist Francis Hayman was working on illustrations for an edition of Pamela, he was commissioned by Jonathan Tyers, the proprietor of the fashionable Vauxhall Gardens, to paint scenes from the novel to decorate the supper-boxes on the south side of the Thames (Keymer and Sabor 159). In 1742, Hayman and the London-based French painter Hubert Gravelot produced a series of engravings for a 1742 edition of the novel published that year (Keymer and Sabor 143). Another well-known painter, Joseph Highmore, embarked on a set of twelve paintings illustrating key scenes from the novel (Figs. 1-5) with the intention of subsequently selling prints by subscription (Keymer and Sabor 163). In February 1744, with ten of the twelve paintings completed, he advertised the availability of “Twelve Prints, by the best French Engravers, after his own Paintings, representing the most remarkable Adventures of Pamela” (Keymer and Sabor 163-164).

Fan makers also cashed in on the salability of Pamela items. In April 1741, the Daily Advertiser announced the arrival of an item, “For the Entertainment of the Ladies, more especially those who have the Book, PAMELA, a new Fan, representing the principal Adventures of her Life, in Servitude, Love, and Marriage. Design’d and engraven by the best Masters” (quoted in Keymer and Sabor 143). The notice informed interested “Ladies” that the Pamela fan was “Sold by M. Gamble, at her Warehouse, No. 19, in Plough-Court, Fetter-Lane; and at all the Fan-Shops and China-Shops in and about London,” suggesting the scope of the Pamela craze. Although no known extant fan survives, correspondence between Elizabeth Postlethwaite and her married sister, Barbara Kerrich, both residents of Norfolk, attests to the availability of this prized possession outside the English capital, the sisters’ familiarity with Richardson’s novel, and their participation in its commercialization (Keyer and Sabor 144).

On April 23, 1745, almost five years after the novel first appeared, the Daily Advertiser promoted a waxworks exhibition of:

“PAMELA; or, Virtue Rewarded [that represented] the Life of that fortunate Maid, from the Lady’s first taking her to her Marriage… The whole containing above a hundred Figures in Miniature, richly dress’d, suitable to their Characters, in Rooms and Gardens, as the Circumstances require, adorn’d with Fruit and Flowers, as natural as if growing. Price Sixpence each.” (quoted in Keymer and Sabor 167)

Although the newspaper urged readers to hasten, “Without Loss of Time… to the ‘Corner of Shoe-Lane,’” Pamela in miniature was displayed for over a year. In fact, just seven months later, in November, another show, “A Curious Representation of PAMELA in High Life,” provided scenes from Richardson’s sequel of the same name (Keymer and Sabor 168). There was also “an equestrian Pamela vogue”—the first racehorse named for Richardson’s heroine “ran at Reading in July 1741” and by the following year, several steeds of that name were “regularly found in the starting line-ups” (Keymer and Sabor 3).

Fig. 1 - Joseph Highmore (English, 1692-1780). Mr.B Finds Pamela Writing, ca. 1743-1744. Oil on canvas. London: Tate Museum, NO3573. Source: Tate

Fig. 2 - Joseph Highmore (English, 1692-1780). Pamela and Mr B. in the summer house, ca. 1744. Oil on canvas; 62.9 x 75.6 cm. Cambridge: The Fitzwilliam Museum, M.Add.6. Source: FITZ MS

Fig. 3 - Joseph Highmore (English, 1692-1780). Pamela in the Bedroom with Mrs. Jewkes and Mr. B, ca. 1743-1744. Oil on canvas. London: Tate Museum, NO3574. Source: Tate

Fig. 4 - Joseph Highmore (English, 1692-1780). Pamela leaves Mr B's house in Bedfordshire, ca. 1743-1744. Oil on canvas; 62.6 x 75.6 cm. Cambridge: The Fitzwilliam Museum, M.Add.7. Source: FITZ MS

Fig. 5 - Joseph Highmore (English, 1692-1780). Pamela is Married, ca. 1743-1744. Oil on canvas. London: Tate Museum, N03575. Source: Tate

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (French). Chapeau à la Paméla, ca. 1801-1802. Engraving. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the novel itself, Pamela’s clothes play a key role in the narrative (Figs. 1-5). As literary historian Carey McIntosh argues, “the peculiar aptness of this symbolic leitmotif in Pamela is a consequence of intrinsic functional relationships between clothing and, on the one hand, sex, on the other, social position” (McIntosh 75). At the beginning of the novel, Pamela receives mourning clothes paid by her late employer, as was customary; however, “Mr. B,” her mistress’s son, also gives her “a Suit of my Lady’s [silk] Cloaths, and half a Dozen of her Shifts, and Six fine Handkerchiefs, and Three of her Cambrick Aprons, and Four Holland ones” (quoted in McIntosh 75). Although she deems them unsuitable for her own use, she reluctantly agrees to wear these garments that set her apart from the other female servants in the house. The ill-intentioned Mr. B. subsequently offers her more finery from his mother’s wardrobe including lace headwear, silk shoes, silver buckles, ribbons, cotton and silk stockings, and “two pair of rich stays” that she later acknowledges “were to be the Price of my Shame” (quoted in McIntosh 76). Later, in anticipation of leaving Mr. B’s house and returning to her farmer parents, she makes herself a “Dress that will become my position…of good sad-colour’d Stuff [wool]” (quoted in McIntosh 75). To accessorize this humble garment suitable for village life, Pamela—who has learned to appreciate more upscale clothing— purchases:

“two pretty round-eared caps, a little straw hat and a pair of knit-mittens turned up with white calico and two pair of blue worsted [wool] hose, with white clocks that make a smartish appearance… and two yards of black ribband for my shift sleeves and to serve as a necklace” from a peddler (quoted in Buck 25).

About to make her departure, she surveys herself outfitted in her “new garb” in a mirror and finds that, “To say truth I never liked myself so well in my life” (quoted in Buck 25).

In Joseph Highmore’s painting of the departure scene (Fig. 4), we see Pamela through the carriage window wearing her “little straw hat” to which she has added blue ribbons. The straw hat, worn by working-class women as well as those of higher status engaged in leisurely country pursuits, would be Pamela’s legacy to fashion. At the end of the century, in 1793, the well-known French actress, Mademoiselle Lange, played the role of Richardson’s heroine in a stage adaptation of the novel, and her “chapeau à la Paméla” was immediately popular. In 1802, a fashion plate in the Journal des Dames et des Modes (Fig. 6) illustrates a young woman in a high-waisted dress and a “chapeau à la Paméla;” the editor noted that although they were “very simple, and therefore very easy to copy, and of an affordable price,” they were still worn exclusively by “the class of opulent women.” Many other iterations of Pamela’s “little straw hat” would follow in the nineteenth century.

Menswear

Menswear of the 1740s did not change significantly from the previous decade. The collarless coat was cut full in the skirts and accented with wide cuffs. The three-piece suit could be matching or, as is often seen in paintings, the coat and breeches were made of the same material and worn with a waistcoat that differed in color and/or fabric.

Maurice-Quentin de La Tour’s portrait of the financier Duval de l’Epinoy (Fig. 1) and an unknown gentleman seated at a table in an understated interior by Arthur Devis (Fig. 2) illustrate a distinct sartorial contrast that reflects the sitters’ deliberate choices for their representations. Notwithstanding their respective social statuses and incomes, the sitters convey what was generally acknowledged on both sides of the Channel: Englishmen preferred a more sober appearance that often included wool and plain linen, while Frenchmen opted for silks accessorized with lace.

Duval’s pale grey silk coat with its rippling moiré pattern dominates the composition with the left sleeve cuff extending well beyond his arm and the full-cut coat skirts, lined in blue silk, escaping from the confines of the damask-upholstered chair. He wears a long-skirted blue silk waistcoat and a lace-trimmed shirt. In his description of La Tour’s “harmony of silvers and blues” that demonstrates the artist’s virtuosity in the pastel medium, art historian Neil Jeffares observes that Duval “wants us to see him not simply as a well- dressed gentleman, but as a scholar and a man of action” (Jeffares 2). He is “caught in the act of taking snuff” while reading from a large volume on his bureau on which is a terrestrial globe is also displayed (Jeffares 2). Forty-nine years old at the time that his friend La Tour created this portrait, Duval wears a conservative style of powdered wig and he has drawn up his white silk stockings over his knee-breeches—an outdated form of fastening by the mid-1740s (Ribeiro 22).

Devis’s sitter, reading a much smaller volume that he has selected from the bookcase opposite, is dressed more simply in a grey wool coat with moderately narrow sleeve cuffs à la marinière (sailor), matching breeches, and a white silk waistcoat. His cravat, tucked into his waistcoat, is plain linen and his shirt is trimmed at the wrists with sheer cotton ruffled cuffs. Unlike Duval whose carefully curled wig required the services of a wigmaker and a valet who had the task of evenly spreading the powder during his master’s toilette, the Englishman has left his brown hair unpowdered and probably tied in an unassuming queue at the back. His white silk stockings were considered the most fashionable and his black leather shoes with rounded toes are secured with small silver-colored buckles.

Fig. 1 - Maurice Quentin de La Tour (French, 1704-1788). Portrait of Duval de l’Épinoy, ca. 1745. Pastel on paper; 120 x 93 cm. Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Inv 2380. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2 - Arthur Devis (British, 1712-1787). An Unknown Man Seated at a Table, ca. 1744-1746. Oil on canvas; 50.8 x 35.6 cm. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1976.7.23. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

Fig. 3 - Arthur Devis (English, 1712-1787). William Farington of Shawe Hall, Lancashire, ca. 1743. Oil on canvas; 49.2 x 33.7 cm. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.228. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: Art UK

Fig. 4 - William Hogarth (British, 1697-1764). Captain Thomas Coram (1668–1751), ca. 1740. Oil on canvas; 238.7 x 147.3 cm. London: The Foundling Museum, FM32. presented by the artist, 1740. Source: Art UK

Fig. 5 - Anna Maria Garthwaite (British, 1690-1763). Waistcoat, ca. 1747. Silk, wool, metallic. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.66.14.2. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1966. Source: The Met

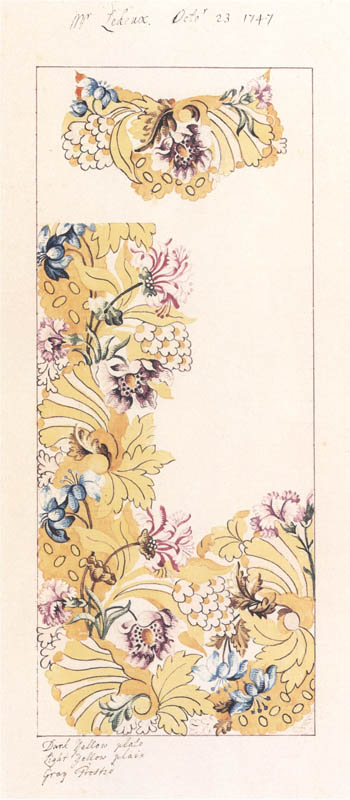

Fig. 6 - Anna Maria Garthwaite (British, 1690-1763). Design for a woven silk "shaped" for a waistcoat, 1747. Pencil, ink and watercolor. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, ber 5985.13. Source: Wikimedia

Another portrait by Devis, William Farrington of Shawe Hall, Lancashire (Fig. 3), depicts this member of the gentry in a frock coat, a style closely associated with the informality of English dress, especially in the country. Posed in a generic landscape with his hound, Farrington’s roomy brown wool frock has a matching velvet turned-down collar and large pockets; his white linen handkerchief trails casually from the left pocket. Dress historian Aileen Ribeiro notes that the frock coat began as as a working-class garment and was adopted by affluent Englishmen in the mid-1720s when it was “first worn for hunting and shooting and other rural pursuits” (Ribeiro 22). Somewhat uncharacteristically for the informality of this garment, Farrington’s black waistcoat and breeches appear to be velvet, with fur or plush lining to his waistcoat.

Like the frock, the ‘surtout’ or greatcoat that also originated from working-class dress “became a fashionable item at first in the Englishman’s wardrobe, and then adopted by the rest of Europe” (Ribeiro 22). This loose-fitting wool coat incorporated “a back vent necessary for riding and a large collar which could be turned up in bad weather” (Ribeiro 22). Just a year after he established the Foundling Hospital in 1739, Captain Thomas Coram (Fig. 4) was painted by William Hogarth, who was also instrumental in this philanthropic venture to care for unwanted babies and children. Coram’s unassuming personality is underscored by his choice of clothing: a brown wool greatcoat over a matching black three-piece suit, plain linen shirt, black stockings, and black shoes. His untrimmed three-cornered hat is at his feet and his white hair is evidence of age, rather than the use of powder.

Although known for—and often depicted in—informal clothing, Englishmen did not shy away from richly woven silks when the occasion called for it. In near-pristine condition and clearly treasured by the original wearer and its subsequent owners, a formal blue silk waistcoat (Fig. 5) is brocaded with a floral-and-foliate design in which the silver and silver-gilt threads are far more abundant than those of polychrome silk. As was typical throughout the eighteenth century, the upper sleeves and back are of a much less expensive fabric (here, wool). Very little information is known today about the wearers and makers of eighteenth-century garments and textiles. Remarkably, Anna Maria Garthwaite’s design for this silk, dated October 23, 1747, is held by the Victoria & Albert Museum (Fig. 6) and it identifies the weaver, Peter Lekeux. Notations on the design specify “the metal threads to be used in the weaving… ‘dark yellow plate’ (a plain, metal strip); ‘light yellow plain’ (a metal strip wound around a silk or linen core); and ‘grey frosted’ (a textured thread that sparkles)” (The Met).

CHILDREN’S WEAR

(BY SUMMER LEE)

Leading into the eighteenth century, attitudes about childhood were changing (Nunn 98). The shift was sparked by new philosophies emerging from the Age of Enlightenment. For example, in his 1693 publication, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, John Locke challenged long-held beliefs about best practices for child-rearing.

However, that was not reflected in childrenswear of the first half of the century. In the 1740s, traditions for childrenswear were not unlike those at the start of the century.

Infants were swaddled, as was the long-held European tradition (Tortora and Marcketti). Swaddling was the practice of tightly binding an infants’ limbs, so as to immobilize them (Callahan). The Victoria and Albert Museum possesses a finely embroidered swaddling band dated circa 1700-1750 (Fig. 1). Its elaborate floral embroidery indicates that this was a fashionable “outer swaddling band” (Victoria and Albert Museum).

In the early eighteenth century, babies typically outgrew the swaddling phase between two and four months (Callahan). They were then dressed in “slips” or “long clothes” (Callahan). These were ensembles with a fitted bodice and a very long, full skirt (Fig. 2) (Nunn 99). Babies also wore tight-fitting caps on their heads.

Once a child was becoming mobile, they transitioned into “short clothes” (Callahan). These ensembles allowed for greater mobility because skirts were cut at the ankle (Callahan). Bodices opened at the back and were boned or otherwise stiffened (Callahan). At this phase, toddlers typically had “leading strings” attached to the back of their bodice (Magidson). Leading strings were streamers of fabric used to protect young children from falling or wandering off (“Childhood”).

When boys were deemed mature enough, they underwent a rite of passage known as “breeching” (Reinier). Breeching referred to the first time a boy wore bifurcated breeches or trousers, symbolizing his entrance into manhood. In the first half of the eighteenth century, boys were typically breeched between the ages of four and seven (Callahan). From that point on, boys during this time followed menswear fashions. Girls did not fully transition into adult dress until their early teens. However, elements of fashionable womenswear were incorporated into their dress as they aged.

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (French). Swaddling band, 1700-1750. Hand embroidered linen; 340.5 cm x 12.5 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, B.13-2001. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 2 - Francis Hayman (English, 1708–1776). Detail of Samuel Richardson, the Novelist (1684-1761), Seated, Surrounded by his Second Family, 1740–1. Oil paint on canvas; 99.5 x 125.2 cm (39.17 x 49.29 in). London: Tate, T12221. Purchased with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund (with a contribution from the Wolfson Foundation) and Tate Members 2006. Source: The Tate Museum

Fig. 3 - William Hogarth (British, 1697-1764). The Graham Children, 1742. Oil on canvas; 160.5 × 181 cm (63.1 × 71.2 in). London: National Gallery, NG4756. Presented by Lord Duveen through The Art Fund, 1934. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 4 - Joseph Francis Nollekens (Flemish, 1702–1748). Children Playing with a Hobby Horse, 1741-1747. Oil on canvas; 45.7 x 55.9 cm (18 x 22 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.491. Source: Yale Center for British Art

A 1742 painting titled The Graham Children depicts the four children of Daniel Graham: Thomas, Henrietta, Anna Maria and Richard (Fig. 3). Thomas, who was less than two years old at the time of painting, wears short clothes and a tight-fitting cap on his head. Henrietta and Anna Maria wear gowns with bell-shaped skirt silhouettes, in solid blue and ivory floral fabrics respectively. They both wear white aprons, frilly sleeves, and flowery headdresses. It should be noted that their stiff, conical torsos are achieved by wearing stays, a predecessor of the corset. In her book, The Corset: A Cultural History, Valerie Steele uses The Graham Children as an example of “the ubiquity of stay-wearing” (Steele 21). On the far right, young Richard wears a men’s suit. His coat and breeches are green and his waistcoat is light brown.

Fig. 5 - Giuseppe Bonito (Italian, 1707-1789). Portrait of Infanta Maria Luisa of Spain, circa 1748. Oil on canvas. Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Another visual resource for 1740s children’s fashions is the painting Children Playing with a Hobby Horse, dated circa 1741-1747 (Fig. 4). On the far left, a young boy wears a red menswear suit with black stockings and a black cap on his head. The other children wear gowns with back-opening bodices and leading strings, both of which are plainly visible on the girl in the dark blue dress. Two girls wear a neckerchief, or fichu, around their necks. The girl on the far right appears to play with a moretta mask.

A portrait of Infanta Maria Luisa of Spain circa 1748 depicts her at the age of three (Fig. 5). Her gown is made of a luxurious pink silk with glittering silver metallic threads, and adorned with flowers and lace. It contains clear markers of childhood: her bodice opens at the back, and she carries a delicate, lacy apron in her arms. The silhouette of her skirt is very wide at the hips, however, mimicking the more extreme court fashions for contemporary womenswear.

References:

- Buck, Anne. Dress in Eighteenth-Century England. London: B. T. Batsford, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1148934170

- Buck, Anne. “Pamela’s Clothes.” Costume, No. 26 (1992): 21-31. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/888619566

- Callahan, Colleen R. “Children’s Clothing.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed August 08, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0003223.

- Chrisman, Kimberly. “Mary Edwards’s Taste and High Life.” Costume, No. 35 (2001): 1-13. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/888619566

- “Childhood.” In European Renaissance and Reformation, 1350-1600, edited by Norman J. Wilson, 319-321. Vol. 1 of World Eras. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2001. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3034600137/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=480f4328.

- De Gregorio, Billy. In Cora Ginsburg: A Catalogue of exquisite & rare works of art including 17th to 19th century costume textiles & needlework. New York, 2019. https://issuu.com/coraginsburg/docs/catalogue_1-single-highres?fr=sNDYyODE1NzQwNzU (Accessed 6/18/21)

- Cunnington, C. Willett. Handbook of English Costume in the Eighteenth Century. London: Faber, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/397113

- Fawcett, Trevor. “Bath’s Georgian Warehouses.” Costume, Vol. 26, No. 1(1992): 32-39.

- “Introduction to 18th-Century Fashion.” Victoria and Albert Museum, January 25, 2011. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/i/introduction-to-18th-century-fashion/.

- Ginsburg, Madeleine. “Ladies Court Dress: Economy and Magnificence.” In The V & A Album, 5, 1988: (142-154). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/902005871

- Jeffares, Neil. “La Tour, Duval de L’Épinay.” http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1177107369 (Accessed 6/18/21).

- Keymer, Thomas, and Peter Sabor. Pamela in the Marketplace: Literary Controversy and Print Culture in Eighteenth-Century Britain and Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/46641908

- Lemire, Beverly. “Peddling Fashion: Salesmen, Pawnbrokers, Taylors, Thieves, and the Second-hand Clothes Trade in England, c. 1700-1800.” Textile History, Vol. 22, No. 1 (1991): 67-82. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/474043958

- Levey, Santina. Lace: A History. London: Victoria & Albert Museum; Leeds: W.S. Maney, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1254027401

- Magidson, Phyllis. “Fashion.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 344-348. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/874270742

- McIntosh, Carey. “Pamela’s Clothes.” ELH, Vol. 35, No. 1 (March 1968): 75-83. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/5552834691

- Nunn, Joan. Fashion in Costume 1200-2000. Bridgewater, NJ: Distributed by Paw Prints/Baker & Taylor, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/232125801

- Pointon, Marcia. Hanging the Head: Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteenth-Century England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/925097861

- Pratt, Lucy, and Linda Woolley. Shoes. London: V & A Publications, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/256750343

- Reinier, Jacqueline S. “Breeching.” In Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood: In History and Society, edited by Paula S. Fass, 118. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2004. Gale eBooks (accessed August 7, 2020). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3402800074/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=360a7a45.

- Ribeiro, Aileen. Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/912425456

- Roche, Daniel. The Culture of Clothing: Dress and Fashion in the Ancien Regime. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/24247707

- “Robe à la française, British, 1740s.” Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/79893. Accessed 6/21/21.

- Rothstein, Natalie, ed. A Lady of Fashion: Barbara Johnson’s Album of Styles and Fabrics. London: Thames and Hudson, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/748992365

- Rothstein, Natalie. Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Boston: Little, Brown, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/246549873

- Steele, Valerie. The Corset: A Cultural History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1013954828

- Stewart, Kristen. “Dress (Robe à la française). In Amelia Peck, ed. Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865169749

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Sara B. Marcketti. “The Eighteenth Century 1700–1790.” In Survey of Historic Costume, 266–297. New York: Fairchild Books, 2015. Accessed August 07, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501304194.ch-010.

- Victoria and Albert Museum. “Swaddling Band.” V&A Collections. Accessed August 08, 2020. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O62960/swaddling-band/.duction-to-20th-century-fashion/.

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/756979502

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600-1930. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1074444804

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1740-1749

Rulers:

- England: George II (1727-1760)

- France: Louis XV (1715-1774)

- Spain:

- Philip V (1724-1746)

- Ferdinand VI (1746-1759)

Map of Europe in 1740. Source: Emerson Kent

Events:

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 18th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.