OVERVIEW

The 1820s were a transitional period away from the “Empire” silhouette and Neoclassical influences. Instead, Romanticism became the chief influence on fashion, as Gothic decoration lavished dresses and historicism inspired styles borrowed from past centuries. Layers of color and an increasingly exaggerated silhouette, for both men and women, created a style of dramatic display by the end of the decade.

Womenswear

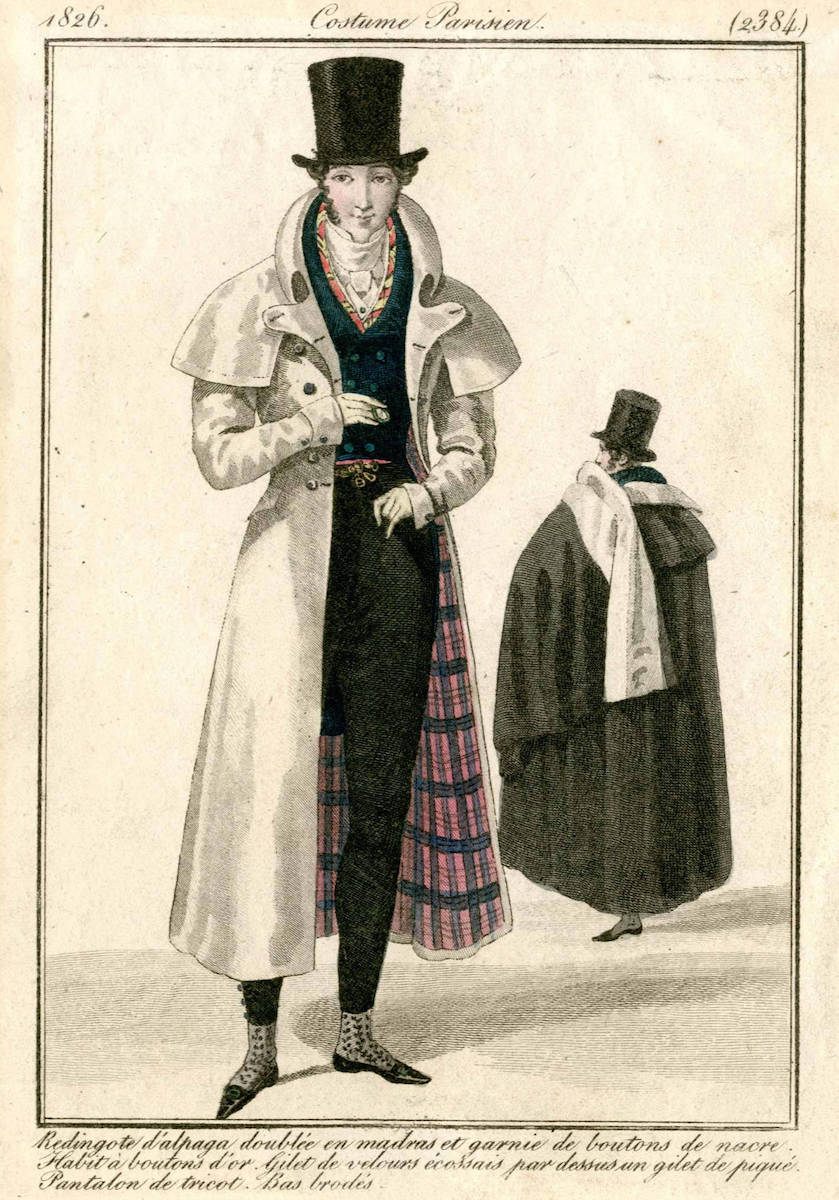

The 1820s were a period of transition in women’s fashion that swept away the last remnants of the Empire style and ushered in a Romantic one, as Gothic influences interrupted the Neoclassical line (C.W. Cunnington 74; Bassett 21). The Romantic Movement, which impacted all aspects of culture and society, was a rejection of eighteenth-century Enlightenment ideals of logic and reason. By the 1820s, it was in full swing, emphasizing imagination, emotion, individualism, and a fascination with the past (Tortora 328; Laver 163). Romantic influence was seen in art, music, architecture, and design, but the average person discovered Romanticism chiefly through literature such as the poetry of Lord Byron and John Keats. In particular, the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott were wildly popular, and helped to spur a historicism that permeated every aspect of dress (Fukai 163; Bassett 16-17). Similar to architects looking to a mysterious medieval past for inspiration, fashionable women wore styles directly borrowed from the supposed costumes of Romantic heroines; it has been noted that “the popularity of Sir Walter Scott is not only to be measured by the number of translations of his works, but also by the amount of tartan worn” (Mackrell 71) (Fig. 1). The Romantic spirit also rejected the Neoclassical preference for clean geometric lines and a monochromatic palette, reflected in the white Empire-style gowns of the early nineteenth century. Instead, by the end of the 1820s, an exuberant fashion consisting of layers of colorful pattern and curvaceous shapes was established (Fig. 2) (Bassett 36-39).

The silhouette underwent important changes during the 1820s. In the first year of the decade, the style was similar to that of the previous few years: the waistline was still high at an inch or two below the bust, the skirt was slightly flared with gores at the sides and fullness gathered at the back, and the sleeves puffed at the shoulder (Fig. 3) (C.W. Cunnington 32, 34; Byrde 35-36). However, the waistline was on the descent, as the Empire silhouette disappeared. Over the next few years, it dropped inch by inch until it was at nearly the natural level by 1825 (Byrde 35). As the waistline dropped, the skirt and sleeves widened; by 1825, the early Romantic silhouette was established with a natural waistline, large puffed sleeves, and a wide skirt with an increasing number of gores (Fig. 4). Through the second half of the 1820s, this silhouette only became more exaggerated. The breadth of sleeves grew exponentially into true gigot or leg-o-mutton styles by 1827, and skirts became so wide that gores were no longer enough and the volume of material began to be pleated into the waistband in 1828. When the decade drew to a close, the waistline was tightly cinched, skirts had expanded into a wide bell, and the gigot sleeve had reached such epic proportions that “the upper arm appeared to be quite double the size of the waist” (C.W. Cunnington 74) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1 - Thomas Lawrence (English, 1769-1830). Marie-Caroline of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, Duchess of Berry, 1825. Oil on canvas; 91 x 71 cm. Versailles: Chateau de Versailles, MV 8505. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (English). Dress, ca. 1828. Printed cotton. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.151 to B-1968. Given by Mrs. H.K. Ludgate. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 3 - Rudolph Ackermann (English, 1764-1834). Fashion Plate: Walking dress, November 1, 1820. Hand-colored engraving on paper; (8.75 x 4.75 in). Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.86.266.302. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Gerald Labiner. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (French). Costume Parisien Fashion Plate, 1825. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (French). Costume Parisien Fashion Plate, 1829. Hand-colored engraving. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, E.22396:137-1957. Given by the House of Worth. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (Canadian). Evening dress, 1823-25. Silk taffeta and satin, cotton lining. Montreal: McCord Museum, M20555.1-2. Source: McCord Museum

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (American). Pelisse-robe, ca. 1820. Silk. Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 2012.24.1. Purchased through a gift from Gloria Gworek. Source: Wadsworth Atheneum

Three-dimensional trim and decoration lavished dresses in the 1820s (Ashelford 184). Skirts in particular were festooned with layers of decoration on the hem (Fig. 6); a trend of frills and tucks began in the previous decade, but in the early 1820s this blossomed into elaborate trims of lace and flounces, puffs, and rouleaux which were tubes of bias-cut fabric filled with wadding to create a firm roll. This weighty decoration caused hemlines to shorten above the floor, and hemlines were padded with cotton or wool (Byrde 36; C.W. Cunnington 34; Johnston 223). In the last years of the decade, this type of decoration began to subside. Instead, deep hems and simpler bands of embroidery or appliqué as high as knee-level were seen. Bodices also featured decoration, especially as the waistline lowered. Trim on the bodice tended to point downwards to converge at the waist (Byrde 40-41).

Sleeves became elaborately decorated as well, and could feature imitations of slashing, puffs, and sleeve caps, or mancherons. These design elements reflected a Romantic historicism that pervaded the decade as they were directly inspired by the dress of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Johnston 46). Edges finished with deep points were called “vandyck points,” a reference to seventeenth-century artist Anthony van Dyck whose portraits served as inspiration (Fig. 7) (Bassett 20). Indeed, 1820s fashion borrowed elements from several hundred years of past dress, ranging from the Medieval period through the eighteenth century, but the Renaissance era was particularly favored (Fukai 125). Early 1820s day dresses were often completed with a ruff at the neck (Figs. 3, 7, 8). Later in the decade, wide, white pelerines were worn which echoed the “falling band” of the seventeenth century (Bassett 28-29; Foster 46).

During the day, necklines were varied, and there were a great many bodice types including versions of plain darted styles, and draped styles with pleats and folds (C.W. Cunnington 76-78; Tortora 332). More open necklines could be filled in with a chemisette, or increasingly through the decade, the wide pelerines previously mentioned (Fig. 5). Sleeves were long during the day. By the late 1820s, there were many types of the gigot sleeve from the very fashionable “Marie” sleeve which was tied into puffed sections (Fig. 9), to the “imbecile” sleeve which was enormous to the wrist (Fig. 10) (C.W. Cunnington 79). There was a particular style of day dress that should also be noted: the pelisse-robe (Fig. 7). Derived from the pelisse, a type of long coat, the pelisse-robe was a coat-dress worn especially in the morning for walking (Tarrant 13; C.W. Cunnington 75). In the evening, necklines lowered, and sleeves generally shortened, although in the early 1820s, long sleeves were sometimes seen. It was especially stylish to wear a short sleeve covered with or attaching to a long, transparent sleeve of gauze or net (Figs. 4, 11) (Byrde 35-36).

Fig. 8 - Charles Howard Hodges (British, 1764-1831). Portret van Alida Gerbade, 1821. Oil on canvas; 72.5 x 59.5 cm. Leiden, Netherlands: Museum de Lakenhal, S 601. Bequest, 1938. Source: Museum de Lakenhal

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (English). Dress and spencer jacket, ca. 1823. Silk. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.28&A-1983. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (British). Dress, 1829. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985.138.2a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn and Alice L. Crowley Bequests, 1985. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (European). Evening dress, ca. 1825. Silk net, silk embroidery, silk satin trim. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2007.211.935. Purchased with funds provided by Suzanne A. Saperstein and Michael and Ellen Michelson. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Fashions of the 1820s favored lightweight silks and cottons in increasingly bright patterns and colors as the decade continued (Byrde 38). Saturated hues such as “Turkey red” and richly printed calicoes were in vogue (Bassett 38-39). In particular, there was a lavish use of laces, net, and gauze. Machine-made net had been patented in 1808, and this novelty fabric saw an explosion in its use (Rose 57). Blonde lace, a bobbin lace woven from silk instead of linen, was also extremely fashionable (Byrde 36). Evening dresses, especially during the early 1820s, were often of a nearly transparent gauze or net worn over a colored satin slip, giving them a shimmering effect (Fig. 11) (C.W. Cunnington 34).

As the fashionable silhouette evolved, so did the corresponding underwear. When the waistline returned to its natural level, corsetry took on new importance, as the smallest possible waist was now desired (Ashelford 184). Indeed, wide waistbands and decorative belts highlighted the fashionable nipped waist (Byrde 35, 41). Tightly-laced corsets were long and featured gussets over the hips and breasts, emphasizing those natural curves (Fig. 12) (Lynn 84; Bruna 160-161). The skirt also required supportive underpinnings. In addition to the requisite petticoats, a small bustle, which was a simple down-filled pad during these years, was worn (Byrde 36). In the late 1820s, as the sleeve became enormous, sleeve supporters also became required; these were usually down-filled pads tied around the arm and attached to the corset straps (Lynn 168; Bruna 161).

Hair and headwear also changed through the decade, becoming more elaborate and extravagant. By the mid-1820s, hairstyles were tall and exaggerated, especially in the evening. The Apollo knot was very fashionable for formal occasions and consisted of tall loops of hair rising straight up from the crown, while sausage curls were arranged at the temples. Similarly, the style à la Chinoise, which appeared at the end of the decade, consisted of tightly arranged plaits and knots with curls at the temple, all skewered with long, decorative pins (Fig. 13) (C.W. Cunnington 95; Tortora 334). Day caps, worn by married or older women at home, grew in breadth and elaboration (Fig. 14) (Ginsburg 75). Most importantly, hats and bonnets of the 1820s expanded into breath-taking size by 1829. Brims widened into large halos around the face, crowns grew ever taller, and trims were loaded onto the enormous structures (Figs. 5, 13). Wide ribbons fluttered, flowers and greenery were used above and under the brim, and feathers bobbed from the crown (C.W. Cunnington 95-96). These overwhelming hats combined with the other elements of fashion to create an effect by 1830 that was summarized well by fashion historian Penelope Byrde:

“Long, fluttering ends of ribbon from the hat or bonnet and waistband of the dress were particularly fashionable, and combined with the shimmering gauzes and blonde lace, there was a feeling of constant movement, buoyancy, and exuberance in women’s clothes when at their best. At their worst, however, these styles could appear wild, fussy, and nonsensical, and the balance was not always easy to maintain.” (38)

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (English). Corset, ca. 1825-1835. Cotton, silk thread, trapunto work. London: The Victoria and Albert Museum, T.57-1948. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 13 - Artist unknown. World of Fashion, January 1828. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Public Library, rbc1076. Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 14 - Christian Albrecht Jensen (Danish, 1792-1870). Baroness Alexandrina Simplicia Nicolai, 1824. Oil on canvas; 64 x 52 cm. Saint Petersburg: The State Hermitage Museum, ГЭ-8338. Source: The State Hermitage Museum

FASHION ICON: MARIE-CAROLINE, DUCHESSE DE BERRY (1798-1870)

Fig. 1 - François Gérard (French, 1770-1837). Marie-Caroline, Duchesse de Berry and her children, 1822. Oil on canvas; 256.5 x 181 cm. Versailles: Chateau de Versailles, MV 4799. Source: Wikimedia

“Marie-Caroline, the Duchesse de Berry was one of the most remarkable, unconventional and iconic women of the 19th century…the undisputed social center of the royal court, the most fashionable and most portrayed princess of her time. Her influence on the fashion of Romanticism was paramount in every sphere…” (Sotheby’s).

Marie-Caroline’s fashion choices reflected the Romanticism of the era, particularly the fascination with the past. Both her clothing and her ever-expanding collection of art were often in the French style troubadour, an offshoot of Romanticism, defined by idealized depictions of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (Mackrell 45, 72). Her dress in figure 1 recalls historic dress with the square neckline, Renaissance-style pearls, and silk puffs in the sleeves imitating slashing. Note the similarities in her portrait in figure 1 in the Womenswear section above; additionally, her tartan hat conjures the novels of Sir Walter Scott, with whose heroines Marie-Caroline identified (Bassett 20; Mackrell 73; Baillio 233). The duchesse also revived the court practice of fancy dress balls, events in which attendees arrived dressed in historic costume. Her most famous took place in 1829; the duchesse organized a fête depicting a scene from the life of Mary Stuart (also known as Mary, Queen of Scots), for which all the court dressed in the fashion of the sixteenth century (Williams 245-247). The costumes from La Quadrille de Marie Stuart, as it came to be known, were reported in the fashion press and undoubtedly reinforced the 1820s obsession with the past (Mackrell 73).

The year following the legendary Stuart ball, the duchesse was forced to flee Paris due to the Revolution of 1830 which ousted the Bourbon dynasty. The next few years of her life were ones of intrigue and adventure as she tried unsuccessfully to restore her son to the throne. The remainder of her life was lived in exile from the city over which she had once reigned. While Marie-Caroline’s power as Paris’ chief tastemaker and fashion leader was short-lived, few women can claim such sartorial influence (Sotheby’s).

Menswear

Like womenswear, men’s clothing was transitional, as it became ever more influenced by the Romantic spirit (Fig. 1). Fashion historian Jane Ashelford noted:

“The Romantic movement stressed the creative power of the ‘shaping spirit of Imagination’ and was motivated by a desire to escape from the chilly neo-classicalism of the turn of the century and the harsh realities of the Industrial Revolution. It manifested itself in dress by an enthusiasm for extrovert personal display and theatrical fashions which, in the 1820s and early 1830s, led to men wearing their clothes with a swaggering bravado and panache.” (189)

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (French). Costume Parisien Fashion Plate, 1826. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

Fig. 2 - George Cruikshank (British, 1792-1878). Monstrosities of 1822, October 19, 1822. Hand-colored etching. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, PC 1 - 14438. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (British). Dress coat and slip waistcoat, 1820-30. Cotton. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.153-1931. Given by Miss E. M. Coulson. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 4 - Artisti unknown (French). Costume Parisien, 1829. Hand-colored engraving. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, E.22396:124-1957. Given by the House of Worth. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (British). Cossack trousers, 1820-30. Silk, cotton lining. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.197-1914. Given by Mr Frederick Gill. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 6 - Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798-1863). Louis-Auguste Schwiter, 1826-30. Oil on canvas; 217.8 x 143.5 cm. London: The National Gallery, NG3286. Purchase, 1918. Source: The National Gallery

Fig. 7 - Thomas Lawrence (English, 1769-1830). Portrait of Frederick H. Hemming, ca. 1824-25. Oil on canvas; (30 x 25 3/8 in). Fort Worth, TX: Kimbell Art Museum, ACF 1963.01. Bequeathed from Mr. and Mrs. Kay Kimbell, 1964. Source: Wikimedia

A man’s wardrobe consisted of many pieces that were chosen based on the time of day and occasion. For formal daywear, a dress coat was worn; this was a tailcoat with the fronts cut straight across the waist and hanging tails in the back (Fig. 3). The morning coat was a variation on the dress tailcoat, featuring instead sloped fronts that curved gently toward the back. For informal daytime occasions, the new frock coat was more and more fashionable. Introduced in mid-1810s, the frock coat featured a waistline seam, tightly-fitted, and full skirts hanging straight to the knee (Fig. 4) (Byrde 91, 95-96; Waugh 112-114).

With both the dress or frock coat, trousers were increasingly worn. Trousers were narrowly fitted and reached the top of the shoe (Laver 162). The wide-cut “cossacks,” inspired by the Russian Czar’s visit to London in 1814, were a notable departure from standard narrow trousers; 1820s cossacks were pleated into a waistband and tapered to a fitted ankle (Fig. 5). By 1825, trousers had replaced their predecessor, pantaloons, as general day wear. Pantaloons were distinguished from trousers by their fit; pantaloons were ankle-length in the 1820s with a buttoned side slit, and very closely fitted, similar to tights (Fig. 1) (Waugh 116). Both trousers and pantaloons featured fall-front openings; while the fly-front fastening first appeared in the early 1820s, it would not come into widespread use until the 1840s. Both were often secured with instep straps around the foot. While pantaloons were seen less and less in the daytime through the decade, they remained the standard choice for evening wear in black or cream, alongside a black dress coat (Fig. 6) (Byrde 91-97). It should be noted that knee breeches could still be occasionally seen in the evening, or paired with boots and a morning coat for riding and sporting (Waugh 116; Tortora 341-342).

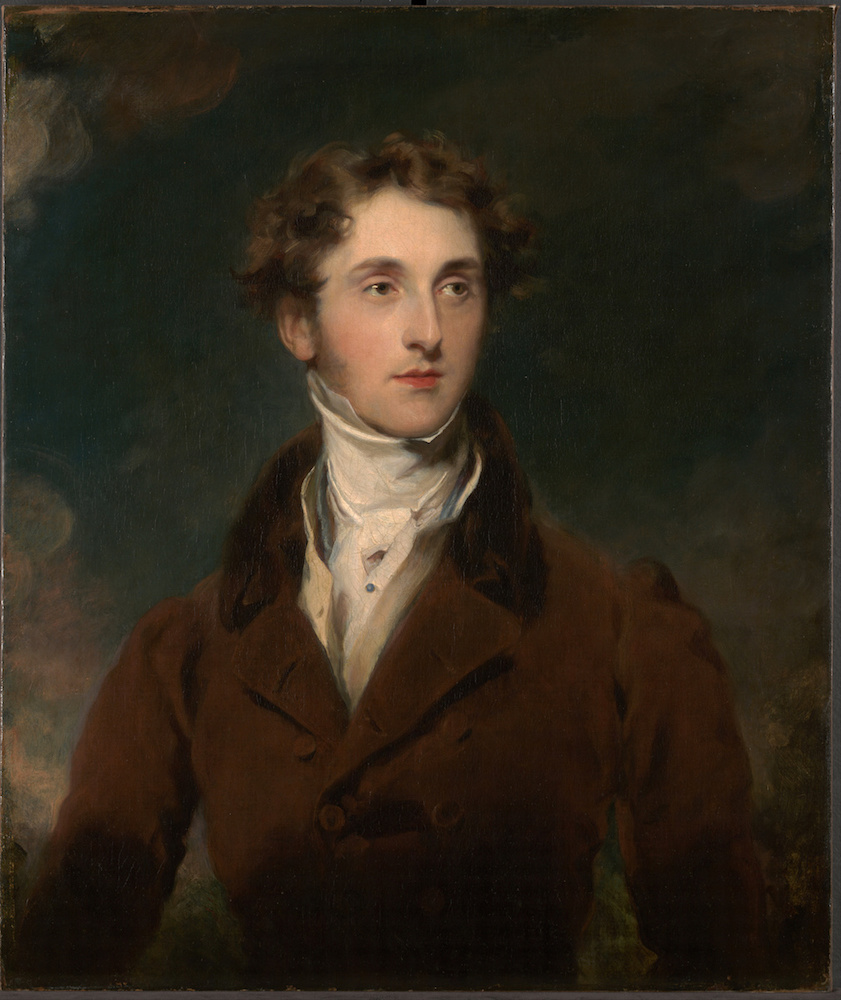

Both dress and frock coats were made in darker colors such as blue, black, brown, and green (Waugh 117). Trousers and pantaloons were usually in a lighter color than the coats. Waistcoats, worn at all times, were usually of some solid color; black or white for evening. They were predominantly single-breasted and featured either a short stand collar or a rolled shawl collar (Tortora 342). It was common to wear more than one waistcoat at a time, increasing the attention on the fashionable large chest (Waugh 115). Shirts were white, with exceedingly tall collars rising above the chin, echoing the high collars featured on coats (Figs. 6-7). During the day, shirt fronts featured pleated or tucked panels, but in the evening they were frilled (Byrde 94).

The final elements of men’s dress were especially important during this era. Neckwear, the chief vanity for dandies, fell into one of two categories: the cravat or the stock. The cravat, a large square of muslin or silk, was folded cornerwise and carefully tied around the neck in a variety of arrangements (Waugh 119; Tortora 341). The stock was a stiffened band, that fastened at the back, covered with velvet or satin. Originating in military dress, the stock became fashionable in 1822, popularized by George IV. The most common colors for neckwear were white or black, but patterned versions could be worn for informal occasions (Byrde 94). At the waist, dangling seals and fobs, which were attached to the watch tucked into a pocket in the waistband, continued to be seen (Ashelford 186; Cumming 83). The top hat was the standard choice for headgear, and its shape and color varied during this period (Ginsburg 76, 85).

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Louis Hersent (French, 1777-1860). Henri-Charles-Ferdinand d'Artois, Duke of Bordeaux and his sister Louise-Marie-Thérèse d'Artois, at the Tuileries, 1821. Oil on canvas; 146.5 x 113.5 cm. Versailles: Chateau de Versailles, MV 4800. Source: Chateau de Versailles

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (American). Child's dress and Pantalettes, 1820-29. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.2324a, b. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - E. W. Gill (British). Basket of Cherries, 1828. Oil on canvas; 117 x 91 cm. London: Bonhams Auctions. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 4 - Henry Raeburn (Scottish, 1756-1823). Walter Ross "The Yellow Boy", ca. 1822. Oil on canvas; 127 x 100.33 cm. Edinburgh: National Galleries Scotland, PG 3312. Bequeathed by John Cook, 2002. Source: Art UK

Fig. 5 - Merry-Joseph Blondel (French, 1781-1853). Two Children in an Empire Interior, 1826. Oil on canvas; 61 x 50.5 cm. Paris: Sotheby's. Source: Sotheby's Pinterest

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (French). Young Woman's dress, ca. 1822. Silk. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, AC1999.46.1. Gift of Helen Larson. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Young girls’ clothing was based on adult fashions; the chief distinguishing feature was the hemline. During the previous decade, dresses for little girls had begun to shorten to ankle-length. By the late 1820s, these hemlines shortened even more, to calf-length. As a girl aged, the hemline dropped until it was an inch or two above the floor in her early teen years (Fig. 6). A girl’s dress reflected the fashionable silhouette and trims of an adult dress, and as the Empire style disappeared in the 1820s, girls’ dress became more cumbersome, similar to women’s dress. The waistline dropped, sleeves grew, and skirts, now with multiple flounces at the hem, widened. Observe the small girl in figure 5 featured in the Womenswear section above. The widening skirt brought the return of multiple petticoats for young girls by the end of the decade (Buck 118, 137, 227). Additionally, as the hemline was shortened, the frilled or tucked pantalettes or drawers young girls’ wore to cover their legs became easily visible (Fig. 5). Drawers had been gaining in popularity for the last two decades, but only in the late 1810s and 1820s did the hem shorten enough for them to be plainly visible. These bifurcated garments for females caused some controversy but were eventually accepted as not only undergarments for girls, but for women as well (Callahan; Buck 135; P. Cunnington 197). Outdoors, spencers and pelisses were worn (Rose 76). Young girls also wore bonnets and hats similar to adult styles with high crowns, wide brims, and trailing ribbons (Buck 139, 242).

References:

- Ashelford, Jane. The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society, 1500-1914. London: National Trust, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/243850605

- Baillio, Joseph, Katharine Baetjer, and Paul Lang. Vigée Le Brun. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083139341

- Bassett, Lynne Z. Gothic to Goth: Romantic Era Fashion and Its Legacy. Hartford: Connecticut Wadsworth Antheneum Museum of Art, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/953101887

- Bruna, Denis, ed. Fashioning the Body: An Intimate History of the Silhouette. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/945435796

- Buck, Anne. Clothes and the Child: A Handbook of Children’s Dress in England, 1500-1900. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/243852072

- Byrde, Penelope. Nineteenth Century Fashion. London: Batsford, 1992. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/26300526

- Callahan, Colleen R. “Children’s Clothing.” in The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 145-149. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Bloomsbury Fashion Central via the New York Public Library. http://dx.doi.org.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0003223.

- Cumming, Valerie ed., The Dictionary of Fashion History. New York: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1003643284

- Cunnington, C. Willett. English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Guide with 1,117 Illustrations. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868281120

- Cunnington, Phillis, and Anne Buck. Children’s Costume in England: From the Fourteenth to the end of the Nineteenth Century. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1978. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/174334043

- Foster, Vanda. A Visual History of Costume: The Nineteenth Century. London: BT Batsford, 1984. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28405843

- Fukai, Akiko, ed. The Collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute: Fashion, A History from the 18th Century to the 20th Century. Kyoto: Taschen, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/81452017

- Ginsburg, Madeliene. The Hat: Trends and Traditions. London: Studio Editions, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/22914760

- Johnston, Lucy, Marion Kite, Helen Persson, Richard Davis, and Leonie Davis. Nineteenth Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publications, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/61302743

- Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/966352776

- Lynn, Eleri. Underwear: Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publishing, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/800448074

- Mackrell, Alice. Art and Fashion: The Impact of Art on Fashion and Fashion on Art. London: B T Batsford, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/316202486

- Rose, Clare. Children’s Clothes: 1750-1985. London: BT Batsford, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/317672212

- Sotheby’s. “Marie-Caroline, Duchesse de Berry (1798-1870)” in “A pair of gilt-bronze-mounted ebony veneered and mahogany console tables.” Treasures Including Selected Works from the Collections of the the Dukes of Northumberland. Last updated July 9, 2014. http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2014/treasures-princely-taste-l14303/lot.56.html

- Tarrant, Naomi E. A. The Rise and Fall of the Sleeve: 1825-1840. Edinburgh: Royal Scottish Museum, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/906444950

- Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865480300

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes: 1600-1900. New York and London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927414537

- Williams, Hugh Noel. A Princess of Adventure: Marie Caroline, Duchesse de Berry. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/645179181

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1820-1829

Rulers:

- England: George IV (1829 – 1830)

- France

- Louis XVIII (1815 – 1824)

- Charles X (1824 – 1830)

- Spain: Ferdinand VII (1813 – 1833)

- United States

- James Monroe (1817-1825)

- John Quincy Adams (1825-1829)

- Andrew Jackson (1829-1837)

Events:

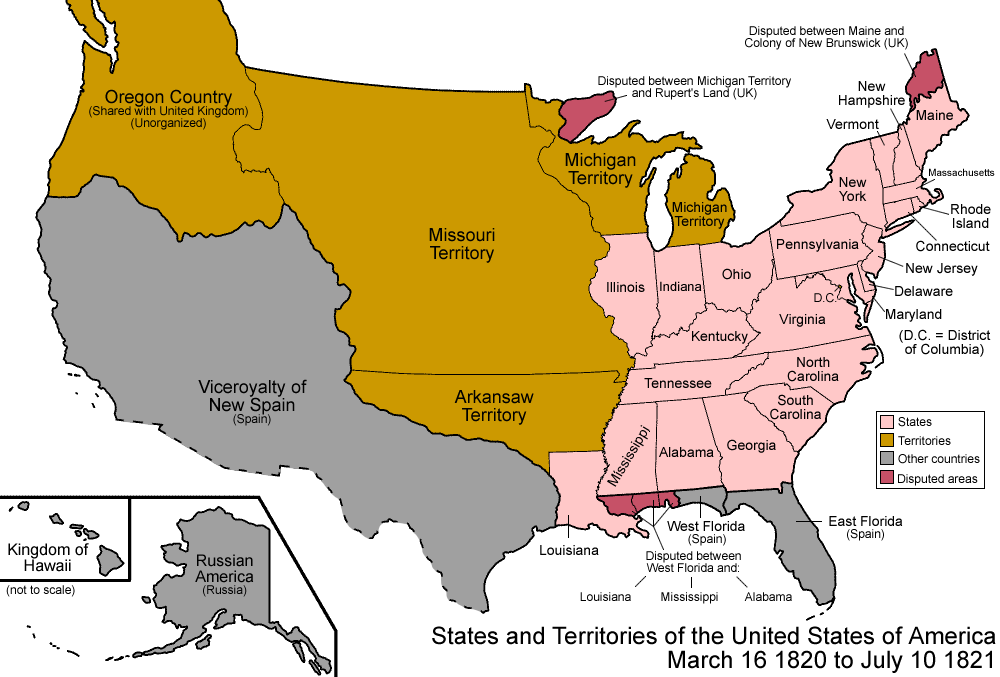

- 1820 – The Missouri Compromise, regulating slavery in the former Louisiana Territory and the proposed state of Missouri, becomes law.

- 1820 – Mount Rainier erupts over what is now Seattle.

- 1821 – The Greek War of Independence begins against the Ottoman Empire.

- 1821 – Napoleon Bonaparte dies on Saint Helena.

- 1822 – Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion publish their translations of the Rosetta Stone.

- 1824 – Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 premieres in Vienna.

- 1825 – The world’s first modern railway, the Stockton and Darlington Railway, opens in England.

- 1827 – Freedom’s Journal, the first African-American owned and operated newspaper in the United States, publishes its first issue.

- 1827 – The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad is incorporated, becoming the first railroad in the the United States to offer commercial transportation of both people and freight.

- 1828 – The Democratic Party is established in the United States.

- 1829 – The Metropolitan Police Service, the first modern police force, is established in London.

- 1829 – First Braille book is published.

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Fashion Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 19th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.