OVERVIEW

The 1890s were a transitional decade from the stiff Victorian Era to a new century. New freedoms and technologies drove an era that became known as the “Gay Nineties.”

Womenswear

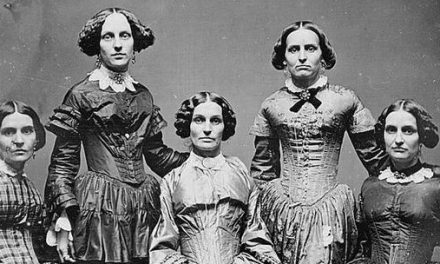

The 1890s were a period of change. As the century drew to a close, the world began to move away from the stiff, moralistic, Victorian Era (Laver 211). Urban centers were growing, and new technologies, such as the introduction of electricity into clothing manufacturing, produced a boom in the ready-to-wear market. Women were enjoying new levels of independence; during the decade the number of women employed outside the home almost doubled (Tortora 380-382). The “New Woman” of the era was an intellectual young female who worked, cycled, and played sports (Fig. 1). Dress historian James Laver wrote:

“The old, rigid society-mould [sic] was visibly breaking up… For the young, there was a new breath of freedom in the air, symbolized both by their sports costumes and by the extravagance of their ordinary dress. It was perfectly plain that the Victorian Age was drawing to its close.” (211)

Fig. 1 - Thomas E. Askew (American, 1850?-1914). Four African American women seated on steps of building at Atlanta University, Georgia, ca. 1895-1900. Gelatin silver photographic print. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, LOT 11930, no. 362. Source: Library of Congress

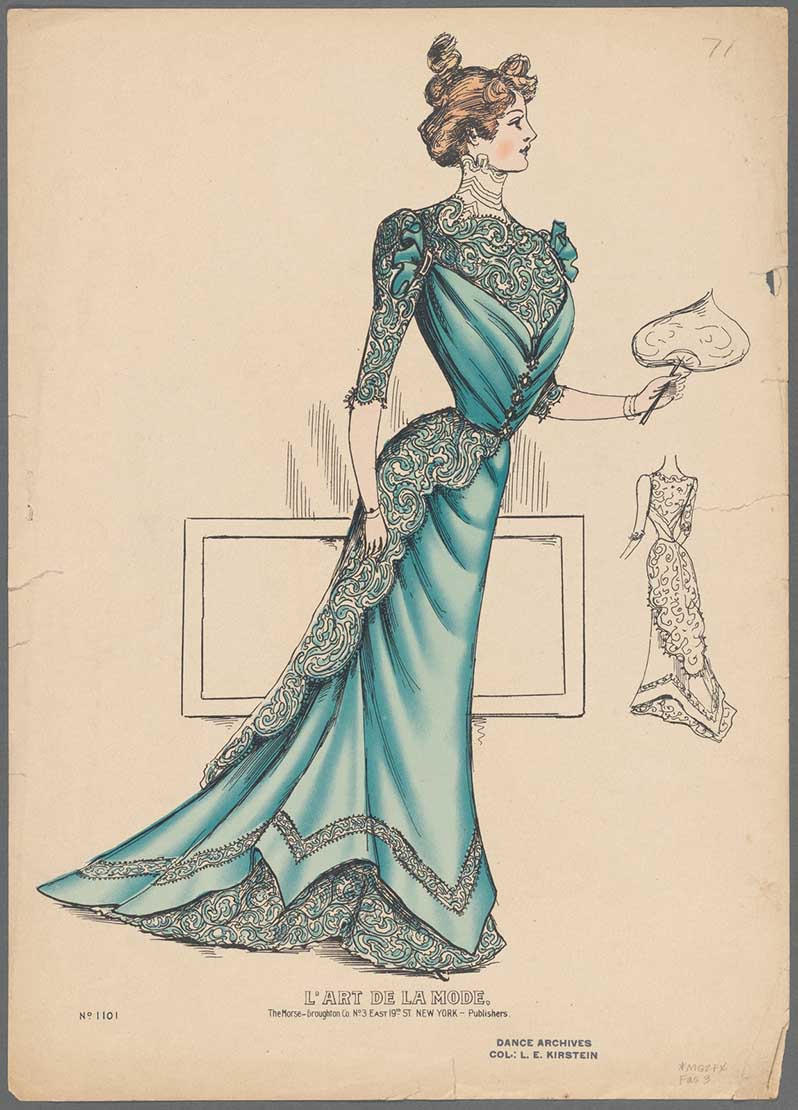

In the first years of the decade, the silhouette was a continuation of the late 1880s style, with the notable development of a small vertical puff at the shoulder (Fig. 2) (Severa 458; 476-481). By 1892, the dramatic, protruding bustle had completely disappeared, and the silhouette most associated with the 1890s took hold (Fig. 3). Skirts were bell-shaped, gored to fit smoothly over the hips, while bodices were marked by the large leg-o-mutton or gigot sleeves. The early puff grew greatly in size, reaching an apex in 1895. The width at the top and bottom of the silhouette was balanced by a nipped waist, to create an hourglass effect (Tortora 397; Shrimpton 26-27). Around 1897, the silhouette began to slowly shift with the introduction of the straight-front corset. Supposedly designed as a healthier alternative, these new corsets forced a woman’s chest forward and hips backward into a curvilinear “S” shape (Fig. 4), that became the dominant silhouette by 1900 (Laver 213).

Fig. 2 - Fisher & Monfort (American). Three quarter length portrait, lady in plaid dress, ca. 1890-1892. Cabinet card photographic print; 17 x 11 cm. New Haven, CN: Yale University: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, 2002225. Source: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown. Morning dress, 1892-1894. Printed silk, silk gauze, velvet. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.368&A-1960. Given by the Comtesse de Tremereuc. Source: Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Fashion Plate, 1899. New York: New York Public Library, *MGZFX Fas 1-8. Gift; Lincoln Kirstein. Source: New York Public Library

Fig. 5 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Mr. and Mrs. I. N. Phelps Stokes, 1897. Oil on canvas; 214 x 101 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 38.104. Bequest of Edith Minturn Phelps Stokes (Mrs. I. N.), 1938. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

As the nineteenth century wore on, the complex set of rules governing dress became ever more intricate, resulting in a dizzying array of recommended ensembles by the 1890s (Ginsburg 176; Font 26). The general delineations of morning, afternoon, and evening wear held throughout the decade. Morning wear featured high necklines and long sleeves, while afternoon clothing opened at the neck and featured shortened sleeves, and finally, evening wear bared the chest and arms. The simplified silhouette was present throughout the day (Tortora 397-400; Font 26-28).

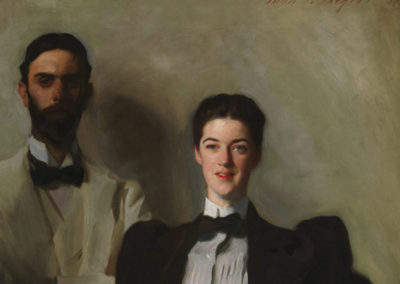

Menswear began to have a significant influence on women’s clothing (Fukai 127). Indeed, perhaps 1890s womenswear is most marked by the shirtwaist ensemble, as captured in John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Mr and Mrs I.N. Phelps Stokes (Fig. 5). It consisted of a simple skirt, and a shirtwaist, or blouse, that was tailored similar to a man’s shirt, but could feature tucks, frills, and lace trimmings (Laver 208). As seen on Mrs. Stokes in the Sargent portrait, the look was often completed with a jacket and straw boater hat. The shirtwaist was worn as standard day wear (Fig. 1), for sporting activities, and most often by the new female workforce, as seen in the photograph of young librarians wearing a variety of shirtwaist styles (Fig. 6). Shirtwaists could also be worn as part of a suit, often referred to as tailor-mades (Tortora 399; Fukai 127). Ranging from simple menswear-inspired looks to more elaborately trimmed, colorful versions, as seen in the fashion plate from the Delineator (Fig. 7), tailor-mades were common choices for morning wear (Shrimpton 27).

Fig. 6 - Photographer unknown. Staff of the Mechanics Institute Reference Library, 1895. Photograph. Toronto: Toronto Public Library, X 71-4 Cab. Source: Toronto Public Library

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. The Delineator, Visiting Toilettes, January 1897. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 8 - C.M. Bell. Allen, J.L.M., ca. 1895. Negative; (5 x 7 in). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, LC-B5- 41888A. Gift; American Genetic Association, 1975. Source: Library of Congress

Women generally arranged their hair in high, neat chignons with soft curls at the front (Tortora 400). Hats were an all-important accessory, and were available in a variety of styles. Usually, 1890s hats were wide and heavily trimmed with tall upwardly curling feathers, ribbons, and flowers (Shrimpton 28). Figure 8 depicts a typical hat of the decade. Often hat trimmings were excessive; a common decoration was an entire stuffed bird. Toques, a hat without a brim, were also fashionable, worn perched at the top of the head (Fukai 126-127).

Outerwear evolved to accommodate the large sleeve, with jackets and coats also featuring the gigot. However, capes became the most fashionable choice as they fell gracefully over the expansive sleeve. Capes could close with a graceful high collar, and were frequently trimmed with jet beading, braid, and fur (Fig. 9). The dolmans of the 1880s fell out of favor, and the cashmere shawl, a woman’s most prized accessory earlier in the century, all but disappeared from the fashionable wardrobe (Severa 464-466;Tortora 400). A commenter noted in 1895 that cashmere shawls were being used to cover pianos, writing “[h]ow the mighty have fallen” (Severa 466).

Fig. 9 - C.R. Smith. Woman in Cape, ca. 1895. Source: Black History Album

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown. Sweater, ca. 1895. Wool. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.1111. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 11 - Columbia. Bicycle Suit, ca. 1895. Wool. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC3318 80-21-4, AC5629 87-20B. Source: Kyoto Costume Institute

While women had been slowly participating in more sports since the 1870s, female participation in sports expanded greatly in the 1890s. Many women’s colleges began adding basketball to standard gymnastic activities. More and more women were playing golf, tennis, croquet, and bathing at the seashore (Tortora 381). Women wore a variety of ensembles to participate in such occasions, ranging from a standard shirtwaist suit to more specialized clothing. The sweater in Figure 10 would have been a possible choice for tennis or golf. The clearly corseted waist and gigot sleeves achieve the fashionable silhouette while the knit fabric would permit movement.

However, no sport entranced the public like the 1890s phenomenon of bicycling. Around 1892, several improvements to the bicycle spurred its adoption as a common form of transportation, and by 1896, the number of bicyclists was an estimated 10 million, an explosion from the approximately 50,000 in 1885 (Warner 118; Tortora 381). Entire magazines, sports clubs, and events were dedicated to the bicycle (Warner 104). While men certainly rode bicycles, the craze was particularly heady around women. The affordable bicycle allowed women a new level of freedom just as many were entering the workforce and demanding female emancipation (Shrimpton 27; Warner 117). The “bicycle suit,” devised to allow for easier cycling, consisted of a jacket and bifurcated bloomers (Fig. 11). Much controversy swirled around the daring “New Woman” in her shocking pants (Laver 208; Shrimpton 80). However, few women actually wore such a bold costume. More often, if a woman desired a specialized cycling costume, she chose a skirt with a deep pleat in the back to allow her to sit on the bicycle while still appearing to be wearing a skirt. The most common choice by women, however, was a shortened simple skirt over their bloomers or a standard shirtwaist ensemble (Fig. 12) (Warner 123-125).

Fig. 12 - Photographer unknown. Women on Bicycles, 1898. Platinum print. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, E.2283:191-1997. The Ashton Collection. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 13 - Charles Frederick Worth (French, 1825-1895). Evening dress, 1894. Silk satin, beaded embroidery. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC4799 84-9-2AB. Source: Kyoto Costume Institute

Fashion of the period also reflected trends prompted by artistic movements and international influences. The Aesthetic Movement, whose origins lay with the Pre-Raphaelite artists, began a dress reform movement in the early 1880s, which continued to have some influence on fashion in the 1890s (Laver 200). After Japan opened to the West in the 1850s, Japonism, the fascination with Japanese art and design, was a pronounced trend throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Accelerated by a flood of imports and International Exhibitions presenting Japanese art, textiles in particular featured cherry blossoms, ayame (iris pattern), chrysanthemums, and motifs borrowed directly from kimono designs, such as the sun design on the evening dress in Figure 13 (Fukai 252-269). The Art Nouveau movement also had significant influence on fashion, particularly later in the decade. With roots in the Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau emphasized stylized forms of nature, sinuous, curving lines, and a sense of movement (Fig. 14). This curvilinear focus worked very well with the S-curve silhouette of the turn-of-the century (Tortora 384).

Fig. 14 - Charles Frederick Worth (French, 1825-1895). Evening dress, 1898-1900. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976.258.1a, b. Gift of Miss Eva Drexel Dahlgren, 1976. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

FASHION ICON: THE GIBSON GIRL

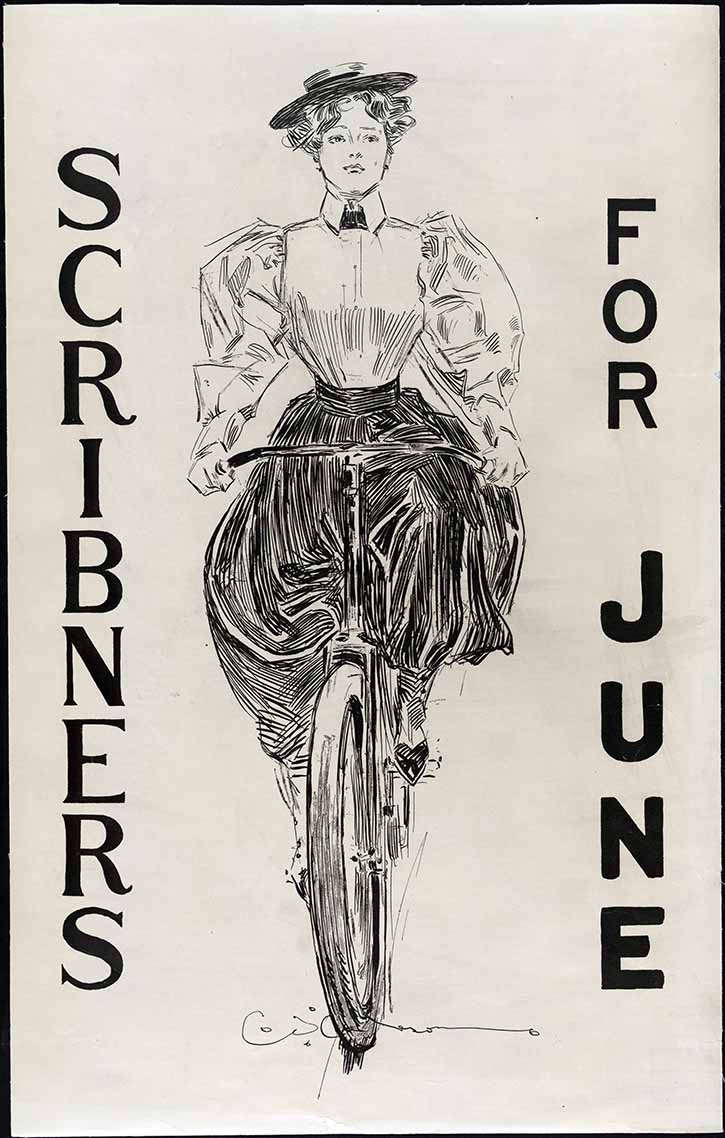

The woman in the illustrations of Charles Dana Gibson was the feminine ideal throughout the 1890s and through the Edwardian Era (Fig. 1). Gibson began creating these drawings around 1890, using various models including, most famously, his wife, Irene (Laver 219). The Gibson Girl became an archetype of American upper-middle class womanhood, a fashionable ideal (Tortora 399). She was flawlessly beautiful with a voluminous hairstyle framing her face. She was slender with a nipped waist, but still attractively voluptuous. Often wearing shirtwaists and tailor-mades, she participated enthusiastically and skillfully in sport (Fig. 2). Most importantly, the Gibson Girl possessed a self-assured grace and a cool confidence, dominant and independent in relations with men, an attitude sometimes associated with the “New Woman” of the period. However, the Gibson Girl was less controversial than the New Woman; she would not have been a suffragette or politically engaged (Wayne).

The Gibson Girl look was imitated across the country. After all, the Gibson Girl was always dressed in the latest, most fashionable mode. The depictions of that confident, sporty woman captured the shifting ideals and newfound freedom of the era. Gibson himself said, “I haven’t really created a distinctive type- the nation made the type…There isn’t any “Gibson Girl,” but there are many thousands of American girls and for that let us all thank God” (Marshall).

Fig. 2 - Charles Dana Gibson (American, 1867-1944). Scribner's for June, cover, June 1895. Lithograph and letterpress poster. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-34349. Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 1 - Charles Dana Gibson (American, 1867-1944). Gibson Girl, ca. 1895. Source: The Gibson Girl Blog

Menswear

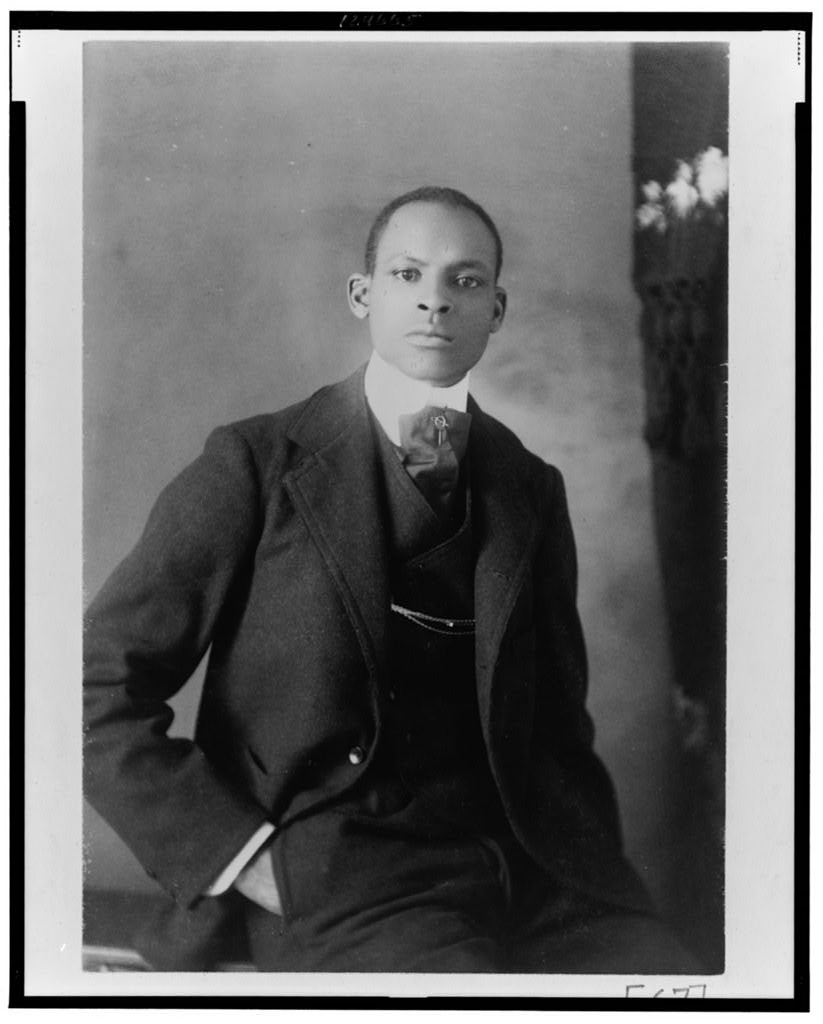

Menswear in the 1890s maintained an overall narrow silhouette, as in the 1880s. However, trousers became slightly more relaxed in cut (Shrimpton 38-40). The frock coat remained fashionable for formal daywear until the turn of the century, as the morning coat slowly supplanted it (Tortora 401). The morning coat, featuring a waistline seam and cutting away in the front, could be quite formal paired with contrasting dark trousers and a top hat, or more casual as a three-piece tweed suit (Fig. 1) perhaps worn by a businessman.

The lounge or sack suit, featuring a single-breasted jacket without a waist seam (Fig. 2), became the most common choice for working men and was increasingly worn by upper-class men as a relaxed alternative day suit (Shrimpton 39). White tie and tailcoats remained the correct dress for evening events, worn with heavily starched, and sometimes pleated, white dress shirts. A dress version of the sack suit, worn with black tie, had been introduced in the 1880s as the tuxedo or dinner jacket (Tortora 401-402). The tuxedo slowly became an acceptable choice for evenings at home or in a gentlemen’s club throughout the 1890s (Laver 205). Figure 3 depicts all of these suit varieties.

Fig. 1 - J.B. Johnstone (British). Morning Suit, 1894. Wool. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.548a–c. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - Photographer unknown. African-American Man, portrait, ca. 1899. Photograph. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, LOT 11930, no. 67. Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 3 - Jno. J. Mitchell Co.. American Fashions: Menswear, August 1899. Print. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-03142. Source: Library of Congress

The shirts of the 1890s were heavily starched and frequently featured stiff stand collars; during this decade the stand collar reached its tallest height at three inches. Collars with turned down wingtips were increasingly worn (Tortora 401). As jackets were more frequently left open, shirts and waistcoats were sometimes made in a playful color (Laver 206). The top hat and bowler remained the most common forms of headwear, the former paired with more formal ensembles. During the 1890s, the bowler hat could be exaggeratedly tall, emphasizing the narrow, tailored look (Shrimpton 38-41). Fedoras, a low, soft hat with a crease from front to back, became increasingly stylish (Tortora 403). Edward VII, then Prince of Wales, popularized a variant of the fedora, called a homburg (Hughes 44).

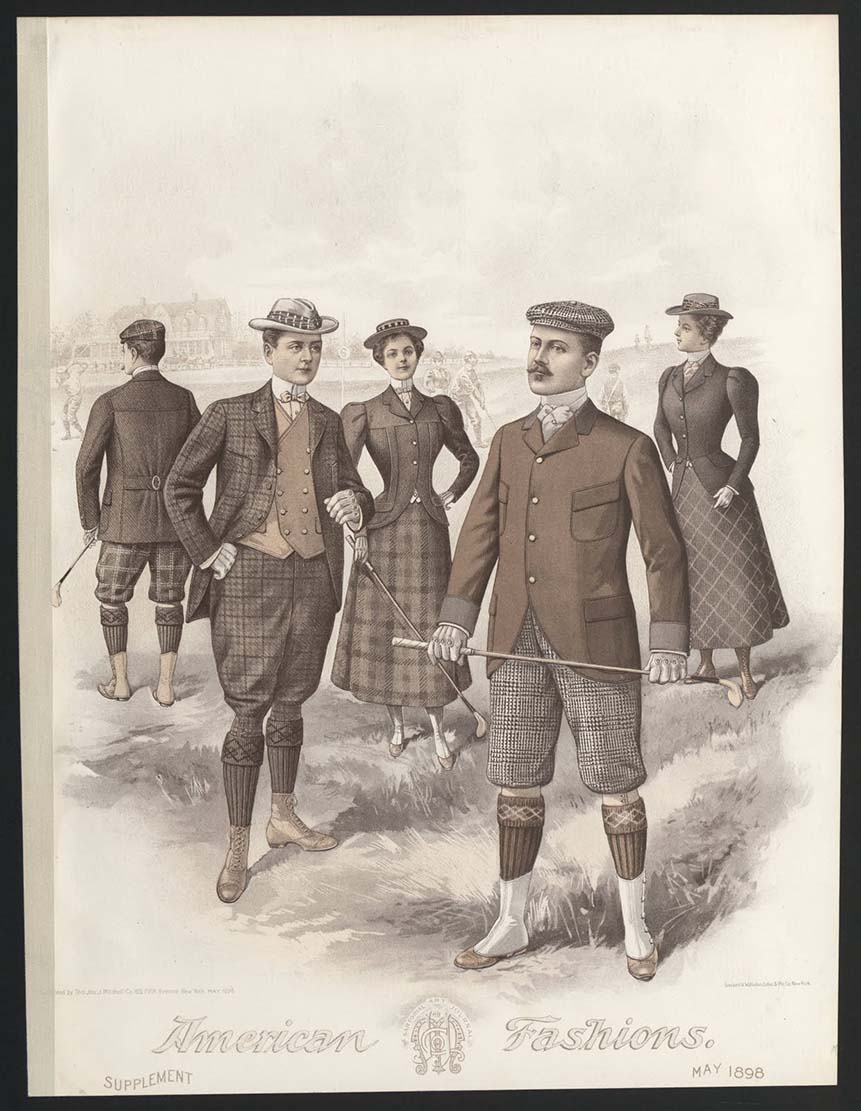

Similar to womenswear, 1890s menswear featured a great deal of sportswear, and those influences were seen in mainstream fashion (Laver 202). Light-colored, often striped flannel, lounge suits paired with a straw boater hat were stylish choices for seaside wear, yachting, and tennis (Shrimpton 40). Mr. Stokes, in the Sargent portrait above wears such a suit. The reefer jacket, square and double-breasted, could be worn without a waistcoat for sporting and seaside activities (Laver 202; Shrimpton 40). For shooting, a tweed Norfolk jacket, with its forgiving vertical pleats and characteristic belt, loose knee-breeches, and gaiters were most appropriate. Men also took part in the bicycle craze, and had a variety of choice: Norfolk suits, lounge suits, and reefer jackets (Laver 202-204; Tortora 401). Figure 4 illustrates a variety of men’s sportswear.

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. American Fashions, May 1898. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Notes from the Victorian Man

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown. Dress, ca. 1895. Cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.932. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - Photographer unknown. The Conner Street Boys, ca. 1898. Source: Kurt A. Meyer

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown. Boy's Little Lord Fauntleroy Suit, 1890. Silk velvet and braid, pewter buttons. Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1948-18-1a--d. Gift of Mrs. Henry W. Farnum, 1948. Source: The Philadelphia Museum of Art

By the 1890s, boys were breeched (given their first pair of pants) as young as three (Tortora 404). Thereafter, a young boy typically wore a suit consisting of narrow knickerbockers buckled below the knee, a shirt frequently featuring an Eton collar, and jacket. Common jacket types included Norfolk jackets, blazers, and lounge jackets with high lapels (Shrimpton 49; Tortora 404). Sailor suits, which first appeared in the 1840s, were also a common choice for young boys (Rose 100, 139-141). Figure 2 depicts all these types. The 1890s also saw the continuation of the fad for “Little Lord Fauntleroy” suits, named for the eponymous protagonist of the 1886 novel (Fig. 3). While the Little Lord Fauntleroy style captured the popular imagination, few boys actually wore the suit. The look was influenced by the Aesthetic Movement and featured a long jacket (sometimes a belted tunic), tight knickerbockers, and a wide lace collar that marked the style. A Fauntleroy boy’s hair was usually styled in long curls as well (Tortora 405).

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Fashion Plate, May 26, 1894. Harper's Bazar. Source: Proquest: Harper's Bazar Archive

Fig. 5 - Photographer unknown. African-American Girl, ca. 1899. Gelatin silver photographic print. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, LOT 11930, no. 212. Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 6 - Liberty & Company (British). Girl's day dress, ca. 1893-97. Silk. Los Angeles: FIDM Museum and Galleries, 2008.25.3. FIDM Museum Purchase: Funds generously donated by Tonian Hohberg. Source: FIDM Museum and Galleries

Girls were dressed as miniature versions of their mothers (Tortora 403). Their dresses, while shorter in length, reflected the fashionable 1890s silhouette for women (Fig. 4). Young girls began wearing training corsets around age thirteen, and their skirts steadily lengthened throughout the teenage years (Shrimpton 49). As with boys, sailor suits were also worn by small girls as seen in the far right of the fashion plate. Girls’ clothing was also influenced by the Aesthetic Movement, in the form of dresses inspired by the idyllic rural illustrations of Kate Greenaway. These children’s drawings depicted young girls wearing loose, high-waisted dresses, and many felt children could move more freely in such clothes (Mitchell 173). Figure 5 is a photograph of a small girl in a “Greenaway dress.” (See also John Singer Sargent’s 1890 portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer). The yoked dress, falling loose from the shoulder to hem, was a similar style (Rose 123). Another important development was the popularization of the smocked dress (Shrimpton 55) as seen in this excellent example in Figure 6. Smocking was associated with innocence (it was also frequently associated with Greenaway looks) and thought ideal for young girls (Mitchell 172).

References:

- Font, Lourdes M. and Trudie A. Grace. The Gilded Age: High Fashion and Society in the Hudson Highlands, 1865-1914. Cold Spring, NY: Putnam County Historical Society & Foundry School Museum, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/77078793

- Fukai, Akiko, ed. The Collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute: Fashion, A History from the 18th Century to the 20th Century. Kyoto: Taschen, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/81452017

- Ginsburg, Madeline. Victorian Dress in Photographs. London: B.T. Batsford, 1982. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/670478733

- Hughes, Clair. Hats. London: Bloomsbury, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1022835787

- Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/966352776

- Marshall, Edward. “The Gibson Girl Analyzed by Her Originator.” New York Times. November 20, 1910. http://sundaymagazine.org/2010/11/the-gibson-girl-analyzed-by-her-originator/

- Mitchell, Rebecca N., ed. Fashioning the Victorians: A Critical Sourcebook. London: Bloomsbury, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1085349620

- Paoletti, Jo B. Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/809762103

- Rose, Clare. Children’s Clothes: 1750-1985. London: BT Batsford, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/317672212

- Severa, Joan L. Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion 1840-1900. Kent, OH: Kent State UP, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/552147475

- Shrimpton, Jayne. Victorian Fashion. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/896980798

- Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865480300

- Warner, Patricia Campbell. When the Girls Came Out to Play: The Birth of American Sportswear. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/655742663

- Wayne, Cynthia. “The Gibson Girl’s America: Drawings of Charles Dana Gibson; Online Exhibition.” Library of Congress. 2013. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/gibson-girls-america/index.html

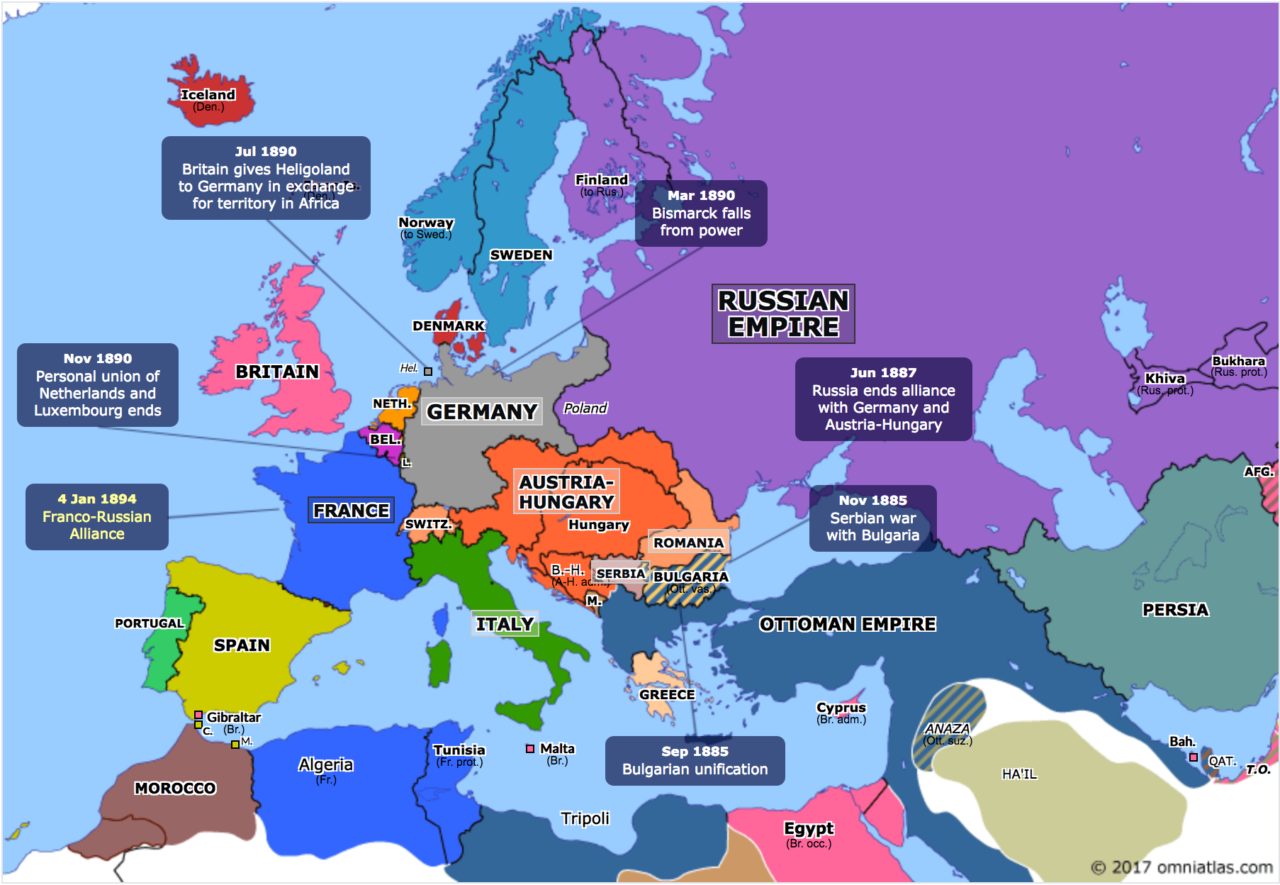

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1890-1899

Rulers:

- Austria-Hungary: Emperor Franz Josef (1848-1916)

- England: Queen Victoria (1837-1901)

- France:

- President Sadi Carnot (1887-1894)

- President Jean Casimir-Perier (1894-1895)

- President Félix Faure (1895-1899)

- President Émile Loubet (1899-1906)

- Italy: King Umberto I (1878-1900)

- Spain: King Alfonso XIII (1886-1931)

- United States:

- President Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893)

- President Grover Cleveland (1893-1897)

- President William McKinley (1897-1901)

Events:

- 1892 – The first issue of Vogue magazine, founded by Arthur Turnure, is published in the US. Viyella (a blend of wool and cotton) is introduced and is popularly used for night wear.

- 1893 – The Panic of 1893 in the United States leads to a severe economic depression until 1896. From May 1 to October 30, the World’s Fair or the World’s Columbian Exposition was held in Chicago.

- 1895 – Guglielmo Marconi invented wireless telegraph.

- 1896 – The first Olympics are held in Athens, Greece since Ancient times.

- 1898 – The Spanish-American War, between Spain and the United States over Cuban Independence, is fought for ten weeks in the summer.

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

- New York Public Library

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Womenswear Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 19th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.