OVERVIEW

The nineteenth century opened with a fashion landscape that was changing dramatically and rapidly from the styles of a generation earlier. The French Revolution brought fashions that had been emerging since the 1780s to the forefront. Neoclassicism now defined fashion as both men and women took inspiration from classical antiquity. For women, the high-waisted silhouette in lightweight muslin was the dominant style, while fashionable men looked to the tailors of Britain for a new, refined look.

Womenswear

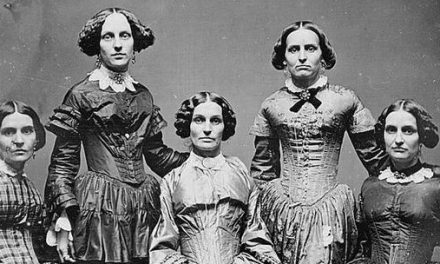

The year 1800 heralded a new century and a new world. The fashion landscape had changed radically and rapidly; the way that women dressed in 1800 stood in stark contrast to the dress of a generation earlier. The wide panniers, conical stays, and figured silks of the eighteenth century had melted into a neoclassical dress that revealed the natural body, with a high waist and lightweight draping muslins (Fig. 1). The origin of this garment was the chemise dress of the 1780s, worn by influential women such as Marie Antoinette and Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (Ashelford 174-175). The chemise dress, in part, reflected a neoclassicism that was beginning to emerge in fashion. Interest in classical antiquity had been growing throughout the second half of the eighteenth century, following the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Classical revivals appeared not only in fashion, but in architecture, the fine arts, and interior design (Davidson 30). However, it was the violently shifting politics at the end of the eighteenth century that spurred this style to the forefront. The French Revolution brought the old world hierarchy crashing down, forever altering dress during the 1790s. The new classical style, imitating the clothing of ancient democracies, seemed to be evidence of a political philosophy on the rise (Tortora 313-314; Byrde 23).

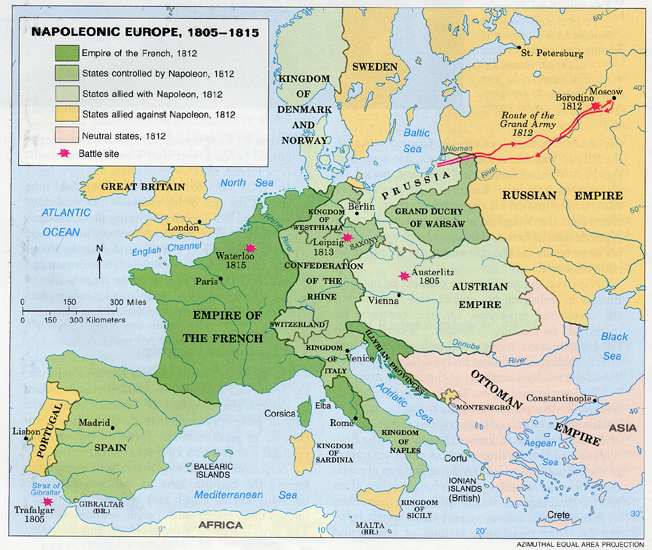

By 1800, the high-waisted silhouette was the prevailing fashion across the Western world (le Bourhis 72). The most extreme manifestations of the Revolutionary classical dress, such as the dampening of gowns so that they clung to the body, were rarely seen after 1800; indeed, those radical fashions had seldom ever been seen outside of France (C.W. Cunnington 26). Still, neoclassicism continued to dominate fashionable dress (Fig. 2). Fashionable women consciously sought to reproduce the supposed fashions of Ancient Greece or Rome. Everything from the hairstyles to the draping shawls evoked antiquity; the preeminence of white as a dress color was due, in part, to the incorrect assumption drawn from classical statuary that classical women only wore white. The slim, vertical line of the garments themselves reflected the neoclassical preference for clean geometry expressed in other visual and applied arts (Byrde 23-24; Tortora 313-314; C.W. Cunnington 26). Fashion historian Philippe Séguy wrote that early 1800s dress “would have been at home in the days of Hadrian” (le Bourhis 73). However, neoclassicism was not the only influence on fashion during the 1800s. Notably, the campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte brought inspiration from all over the world. For example, his occupation of Egypt popularized turbans for evening wear, and sketches of Egyptian ruins inspired palm motifs (Tortora 313; Foster 13). Towards the end of the decade, Spanish ornamentation, such as slashed sleeves, and a heavy use of fur imported from Russia, Poland, and Prussia was the result of Napoleon’s incursions in those countries (le Bourhis 108-109; C.W. Cunnington 27). Gothic ornament began to appear by 1810, and fanciful elements of pastoral dress were also seen (Byrde 24).

In addition to the very high waistline, directly under the bust, the signature feature of womenswear was the prominent use of fine cotton muslin; it achieved a lightness and drape that could not be accomplished with wool or silk (Byrde 23; Foster 12). The main form of dress construction was the “stomacher” or “fall front” dress. This consisted of a bodice front attached to the skirt which was partially cut in a flap; once the wearer pulled on the sleeves and fastened the inner bodice lining, the skirt flap was pulled up where it was fastened with ties around the “waist” and the bodice front was pinned into place (Johnston 166; C.W. Cunnington 31-32). Figure 3 illustrates this construction method. This type of dress was known as a “round gown.” Around 1804, some dresses were made with button fastenings up the center back of the bodice; these were referred to as frocks (Davidson 26).

Fig. 1 - Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825). Madame Récamier, née Julie (known as Juliette) Bernard, 1800. Oil on canvas; 174 x 224 cm. Paris: Louvre Museum, INV. 3708. Acquired at the sale of David's studio, 1826. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (Indian for the Western market). Dress and Kashmir Shawl, ca. 1800. Cotton muslin with silk embroidery. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Dress: M.2007.211.867, Shawl: M.45.3.150. Purchased with funds provided by Suzanne A. Saperstein and Michael and Ellen Michelson, with additional funding from the Costume Council, the Edgerton Foundation, Gail and Gerald Oppenheimer, Maureen H. Shapiro, Grace Tsao, and Lenore and Richard Wayne. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (British). Fall-front gown, ca. 1805-1810. Silk. Canberra: National Museum of Australia, 2005.0005.0141. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (British). Fashion Plate: "London Dresses for September" for "Ladies Museum", September 1808. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Public Library, rbc0238. Source: Los Angeles Public Library

Fig. 5 - Jean-Bernard Duvivier (Belgian, 1762-1837). Portrait of Madame Tallien, 1806. Oil on canvas; (49 1/2 x 36 3/4 in). New York: The Brooklyn Museum, 1989.28. Healy Purchase Fund B. Source: The Brooklyn Museum

Dresses saw minor changes during the 1800s, losing much of the rounded volume of the previous decade. By 1810, skirts were much straighter, and the fullness that was left in the skirt was concentrated at the back, while the front was flat, falling straight to the floor (Fig. 4). In the early years, long trains were common on fashionable gowns, for both day and evening wear, but these began to gradually disappear around 1807 (Byrde 24; Foster 21, 29). The straighter, slimmer appearance of the 1800s was also echoed in the bodice back which featured seams that created a distinctive “kite” or “diamond” shape and gave a very slim, small-backed effect. Finally, straight, narrow sleeves too reinforced the clean lines (Davidson 26; Johnston 56).

Importantly, part of the neoclassical ideal was the beauty of the natural, nude body. Fashion legends abound that tell of women leaving off their stays entirely, and appearing with very little underwear at all; while it seems that some women really did abandon their stays, the practice was not widespread or mainstream. Instead, nudity was suggested in the revealing cut of dresses. Large portions of the chest and back were bared even in day dresses, sleeves were short, and draping muslin revealed the shape of the leg (Fig. 5) (C.W. Cunnington 28; Davidson 63-64; Laver 155). Of course, this new style of dress did force a change in underwear. The narrowed skirt only required a single petticoat; indeed one was necessary for modesty beneath the nearly-transparent muslin (Byrde 25). Both long and short stays were worn; the new term “corset” referred to lightly boned or even simply corded supports, and these were often worn instead of stays. The chief goal of any supportive undergarment was to raise and shape the breasts, as their natural roundness was desirable for the first time (Davidson 64). Finally, throughout the decade, the fullness in the back of the gown was supported by a bustle pad attached to the inside of the skirt (Johnston 166; C.W. Cunnington 32-33).

The neckline of dresses, for both day and night, was quite low and could be either square or V-neck. During the day, the low neckline could be filled in with a chemisette or tucker (Foster 22). In the early years, the most fashionable sleeve was short for both day and night. Later in the decade, long sleeves were also worn, and they began to gain some fullness at the sleeve head (Davidson 288-289). In the evening, there was a fashion for short overdresses or tunics which borrowed from the ancient Greek chlamys (Fig. 6). While white was considered correct for evening, the nearly transparent muslins were sometimes worn over colored silk slips, creating shimmering pastels (Fig. 4) (Byrde 25-27; C.W. Cunnington 29-30).

Textiles of the 1800s were often enriched with embroidery, one of the few elements permitted to disrupt the classical line. Whitework, colored and gilt threads, and chenille were all employed to decorate gowns with a variety of embroidered designs (Figs. 2, 7) (Johnston 146, le Bourhis 95, 104). While white was undoubtedly the most modish color for dresses, it was difficult and costly to maintain. Sturdier printed cottons and patterned silks were common for daywear, and warmer wools were acceptable in the winter months (Figs. 3, 8) (Byrde 27).

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (British). Fashion Plate: "Paris dress", October 1801. Hand-colored etching; 17.78 x 10.16 cm. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, E.564-1956. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (French). Dress, 1805. Cotton gauze embroidered with wool and cotton. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 22.665. Gift of Miss Eleanora Curtis. Source: Museum of Fine Arts

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (British). Dress (round gown), ca. 1802. Printed cotton. Melbourne, Australia: The National Gallery of Victoria, D111.a-b-1974. The Schofield Collection. Purchased with the assistance of a special grant from the Government of Victoria, 1974. Source: The National Gallery of Victoria

A discussion of 1800s textiles would be incomplete without mention of the resurgence of French silk. In 1804, Napoleon declared the Empire, becoming Emperor, and he revived the luxury and pomp of the ancien régime, instituting lavish court dress once again. Napoleon gave the silk industry a much-needed boost in an imperial decree that French silk be worn at formal ceremonies (Fig. 9). The imperial commissions alone saved the French fashion industry which had been decimated during the Revolution (Fukai 125; le Bourhis 84-94, 100). While Paris was the center of women’s fashion, the best cottons originated in Britain and India; Napoleon forbade the wearing of foreign cotton in order to stimulate French manufacturing. His wife, Joséphine, was the most fashionable woman of the era, the undisputed leader of la mode, and she negotiated the contradictions of a fashion that preferred simple muslin with the demands of court dress expertly (Fig. 10) (Jensen).

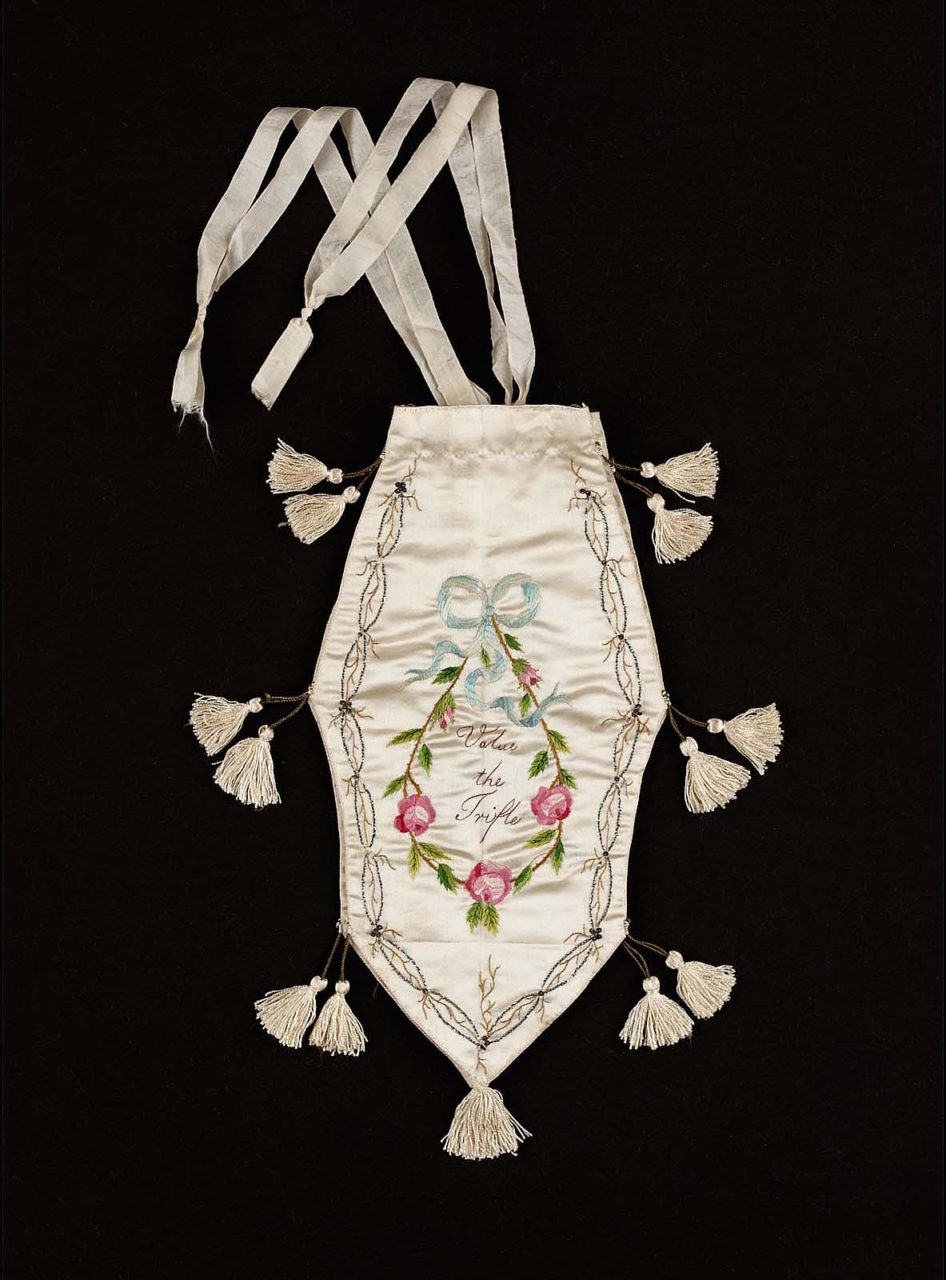

Outerwear and accessories were essential elements of the period, often introducing pops of color (Ashelford 178). By far, the most important accessory of the neoclassical period was the shawl, specifically Indian kashmiris/cashmere (Figs. 2, 5). Lightweight muslin gowns did not provide much protection from the cold, and shawls became a necessary accessory; not only did they provide warmth, they added to the classical draped effect. Imported Indian shawls were wildly expensive luxuries, and a favorite of Empress Joséphine (Fig. 10) (Jensen). European weavers quickly began to create cheaper imitations, most notably in Paisley, Scotland, and that city’s name would become synonymous with the pine or buta/boteh motif (Laver 155; Johnston 40; le Bourhis 77, 81). Other forms of outerwear included the pelisse (Fig. 11) and the redingote, both types of coat, and the spencer, a cropped jacket (Ashelford 179; C.W. Cunnington 34-38). Other smaller accessories also mark the era, such as swansdown boas and large fur muffs. Notably, the reticule, a small drawstring handbag, became a standard element of a woman’s outfit (Fig. 12). Reticules became essential as the era’s narrowly-cut skirts prevented the wearing of pockets beneath the dress (Byrde 25-29).

Hairdressing further underscored the classical inspiration of the era; styles were frequently given names from antiquity such à l’Agrippine and à la Phèdre (le Bourhis 80). The most extreme style was à la Titus, in which the hair was cropped short and messily tousled. More frequently, a woman’s hair was arranged in ringlets and curls, often entwined with bandeaux, ribbons, and jeweled combs (Figs. 1, 5, 10) (Tortora 317; Foster 22, 26). There was an astonishing variety of millinery. Jockey caps, lavish evening turbans, wide-brimmed bonnets, face-shielding poke bonnets, and veiled caps were all modish choices (Figs. 4, 6, 13) (C.W. Cunnington 29, 52-53).

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (French). Court costume, ca. 1809. Silk, metal thread. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 32.35.10. Rogers Fund, 1932. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 10 - Pierre-Paul Prud'hon (French, 1758-1823). The Empress Joséphine, 1805. Oil on canvas; 244 x 179 cm. Paris: Louvre Museum, R.F. 270. Assigned to the Louvre, 1879. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (English). Pelisse, ca. 1809. Silk. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.24-1946. Given by Miss M. D. Nicholson. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (English or American). Reticule, ca. 1800-1810. Silk; 27 x 20 cm. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 64.692. Bequest of Maxim Karolik. Source: Museum of Fine Arts

Fig. 13 - Artist unknown (British). Fashion Plate: "London Head Dresses", ca. 1804. Hand-colored stipple engraving; 22.2 x 13.5 cm. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, E.1015-1959. Given by Mr James Laver CBE. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fashion icon: George bryan “Beau” brummell (1778-1840)

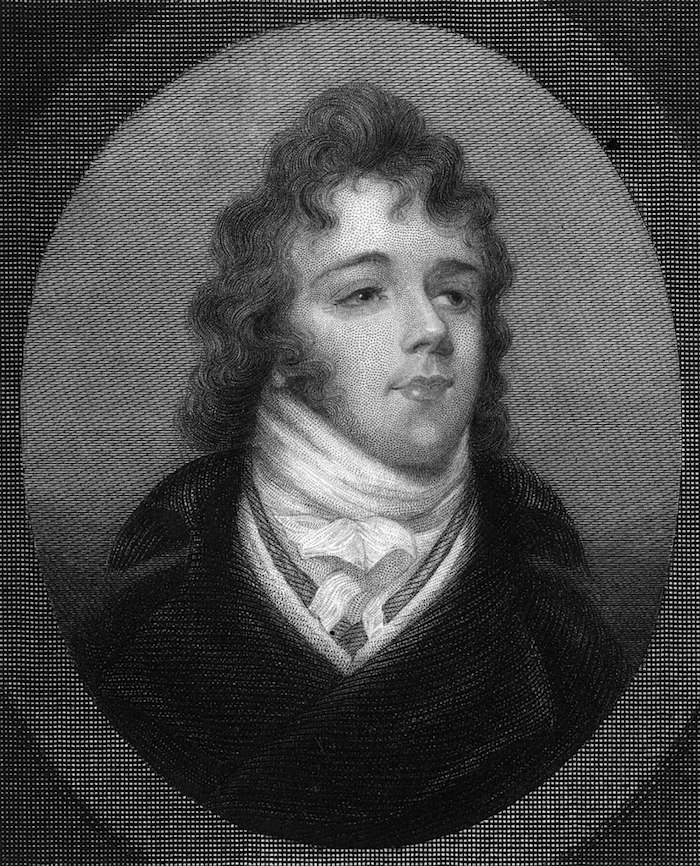

Brummell wore an immaculate suit of pantaloons, blue dress coat, starched cravat, and polished hessian boots (Figs. 1-2). This was not an innovation; it was simply the English country dress that was on the ascendancy throughout western menswear. However, Brummell took this style and “best distilled it, fusing the wearer and the dress in his person” (Davidson 201). He elevated the style with painstaking perfection. In an era in which fit was paramount, his was impeccable. The instep strap on pantaloons is attributed to Brummell as a mechanism to maintain a taut line (Byrde 94). Neckwear was his chief vanity; his exactitude about the quality of his cravat became the stuff of fashion legend. It is said he was the first to starch the cravat, achieving a crispness that resulted in a splendid knot (Davidson 202). A famous anecdote recalls a visitor finding Brummell and his valet next to a pile of crumpled cravats. When the visitor inquired about them, the valet responded, “Those, sir, are our failures” (Laver 160).

Importantly, while great effort was required to maintain Brummell’s style, it was meant to appear as if it had not. Unlike some of the ostentatious dandies of later eras, Brummell’s emphasis was on restraint and simple elegance. He eschewed flippant fineries, rejecting showy, colorful fashions. His was a dandyism of austere refinement, one in which the man shines through the clothes (Byrde 94-95; Cicolini). Davidson wrote:

“Brummell epitomized a new standard of elegance and ideal of perfection in male dress without being a flamboyant dresser. He helped to strengthen the reputation of the English as standard setters for fashionable male dress…the studied epitome of the unstudied riding-dress style seen as English taste.” (202)

Fig. 1 - John Cook after an unknown minaturist (British, Active 1843-44). Beau Brummell, ca. 1800. Stipple and engraving; (9 1/4 x 5 3/4 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG D1124. Given by Henry Witte Martin, 1861. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 2 - Robert Dighton (British, 1752-1814). Beau Brummell, 1805. Watercolor; 32.5 x 23.5 cm. Source: Bonhams Auctions

Brummell is still considered a true fashion icon and the foundation of dandy theory and philosophy. Jules Amédée Barbey d’Aurevilly wrote Du Dandysme et de Georges Brummell in 1845, which raised dandyism to the level of a philosophical and intellectual pursuit, a trend that continued throughout the nineteenth century. Brummell has been recreated in plays and Hollywood films, and modern menswear brands still invoke his name to represent quality and refinement (David). Beyond fashion, Brummell represented many of the larger shifts of the era and foreshadowed trends to come:

“Beau Brummell captured in the turn of his cuff and the knot of his cravat the studied irony and languor that defined his age…[his posturing] aptly crystallized the uncertainty of a period that witnessed the decline of aristocracy and the early rise of democratic politics…in many ways he anticipated the modern era-a world of social mobility in which taste was privileged above birth and wealth. Elevated as a style icon, he presaged the contemporary dominance of fashion and celebrity.” (Cicolini)

Menswear

Just as women’s clothing had undergone a radical change following the French Revolution, so had men’s. A growing Anglomania was shifting menswear even before the Revolution. The restrained riding costumes worn by English gentlemen on their country estates had been increasingly the preferred style in Britain and on the Continent (Fig. 1). However, the new era brought forth by the Revolution saw the English style find its full expression. Fashionable menswear now consisted of un-ornamented wool in dark colors; gone were the floral silk embroideries and fussy lace accessories of the eighteenth century (Laver 149; Byrde 89-91). This change further separated menswear from womenswear. Color and adornment became the nearly-exclusive prerogative of women’s fashion. A “separate spheres” ideology began to take hold during the 1800s, with men increasingly involved in serious business pursuits outside the home as the Industrial Revolution continued and women relegated to dependent caretakers inside the home. This trend soon solidified and defined the remainder of the nineteenth century. Indeed, while both women’s and men’s clothing was radically changing, the shift in menswear was much longer lasting, with its impacts felt even today (Davidson 30; Byrde 91; le Bourhis 116-117). Fashion historian Aileen Ribeiro summarized these shifts, writing:

“For most of the eighteenth century there was a sartorial harmony in the dress of men and women; they were united in their love of color, elegant design, and luxurious materials. One of the results of the French Revolution was to divide the sexes in terms of their clothing. Men’s dress becomes plain in design and sober in color; it is unadorned with decoration. It symbolizes gravitas and an indifference to luxury-essential elements of republican austerity; its virtual uniformity emphasizes the revolutionary ideal of equality.” (141)

Indeed, this shift also furthered separated court costume from general wear. Attendance at royal occasions throughout the courts of Europe remained events where ostentatious costume, much more akin to eighteenth-century dress, was required. Dress historian Hilary Davidson wrote that men’s court clothing during the early nineteenth century “was the last bastion of eighteenth-century styles” (210). Notably, as discussed in Womenswear, Napoleon brought back the court costumes of the ancien régime, which had disappeared in France during the Revolution. A matching silk suit, differentiated from pre-Revolutionary suits only by minor evolutions in cut and the scale of the embroidered motifs, was required at the Tuileries Palace (Fig. 2) (le Bourhis 109-112). Court costumes, increasingly diverged from fashion, continued for decades (Marschner).

Fig. 1 - Sir Henry Raeburn (Scottish, 1756-1823). Professor John Wilson (nom de plume, "Christopher North"), 1785-1854, ca. 1805-1810. Oil on canvas; 236 x 149.30 cm. Edinburgh: National Galleries Scotland, PG 708. Given by the Royal Scottish Academy 1910. Source: National Galleries Scotland

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French). Court suit, ca. 1810. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.1001a–c. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - François-Xavier Fabre (French, 1766-1837). Portrait of a Man, 1809. Oil on canvas; 61.5 x 50 cm. Edinburgh: National Galleries Scotland, NG 2548. Purchased with the aid of the Art Fund (Scottish Fund) 1992. Source: National Galleries Scotland

Fig. 4 - William Owen (English, 1769-1825). Captain Gilbert Heathcote, 1801-1805. Oil on canvas; 127 x 101.8 cm. Birmingham, U.K.: Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, 1938P680. Purchased, 1938. Source: Birmingham Museums Trust

Fig. 5 - Robert Lefèvre (French, 1755-1830). Portrait of Count Andrey Bezborodko, 1804. Oil on canvas; 225 x 165 cm. Saint Petersburg, Russia: State Hermitage Museum, ГЭ-5670. Entered the Hermitage in 1923; transferred from the Stroganov Palace Museum in Petrograd. Source: State Hermitage Museum

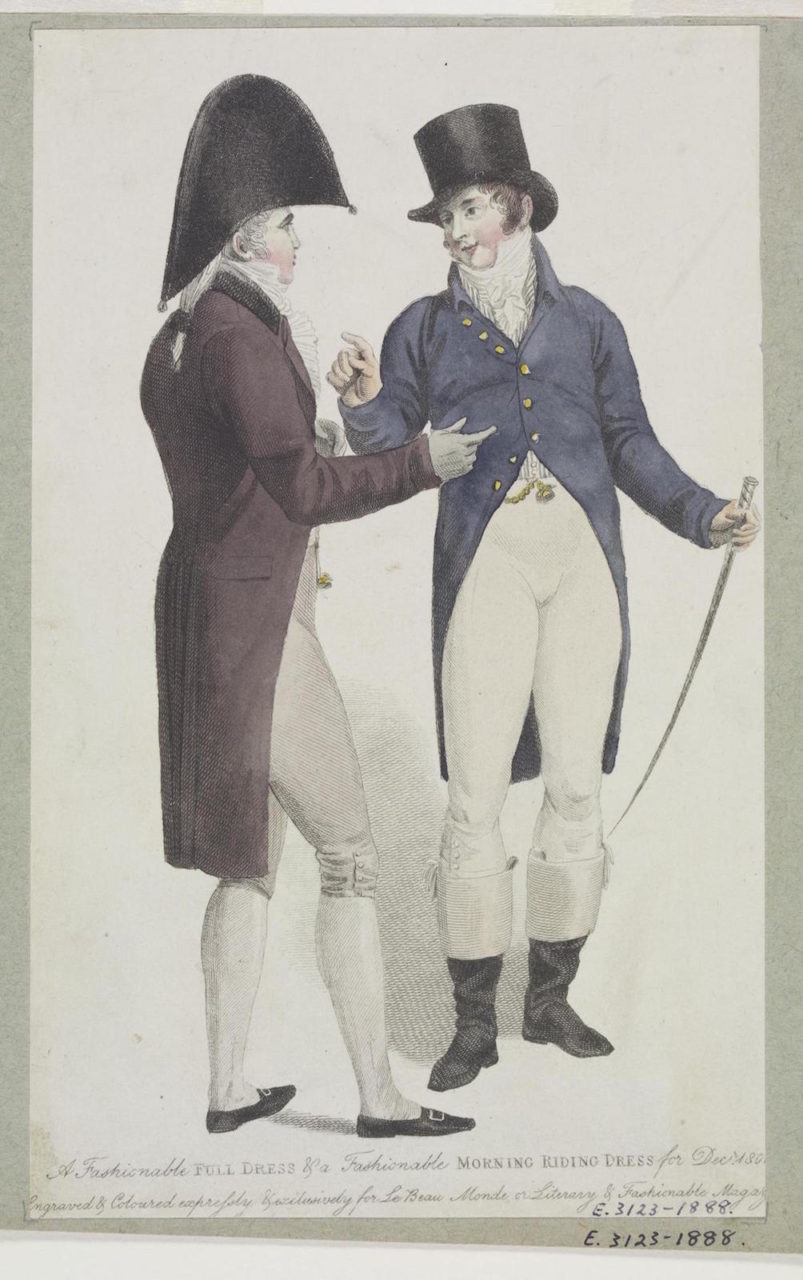

The influence of neoclassicism could also be seen in fashionable menswear. Breeches and pantaloons were often made of jersey or wool cut on the bias, providing an incredibly close fit, which when combined with the cream color often chosen, gave a revealing, almost nude effect; like the draperies of women’s gowns, this effect recalled Greek or Roman statues (Byrde 90; Ashelford 185). Beginning in the previous decade, men abandoned the practice of powdering their hair and cropped it short, creating a natural, tousled appearance (Fig. 3). These new hairstyles were referred to as à la Titus or Brutus, underscoring their classical inspirations (Davidson 57; Laver 153). The Napoleonic Wars also influenced menswear, as men in uniform dominated life (Fig. 4). The uniforms of the Napoleonic Wars were some of the most lavish and elaborate in history, showing “an unparalleled deployment of rich costumes, a veritable explosion of panache” (le Bourhis 179). The braid, frogging, Brandenburg buttons, and tassels served as inspiration in civilian men’s and womenswear for years (Johnston 14, 20). The prevailing fashion for pantaloons tucked into boots was, at least in part, inspired by the military; the ultra-fashionable hessian boots, defined by their cleft tops trimmed with tassels (Fig. 5), were borrowed from the German Hessian soldiers, and a different, more practical style was named for British military hero, the Duke of Wellington (Davidson 232).

Luxury in menswear was now expressed through a perfect fit of each element of a man’s wardrobe, and Britain’s exceptional tailors led the way (Waugh 112). The three basic elements were the coat, the waistcoat, and breeches or pantaloons. It was rare for all three pieces to be the same color. There were two main types of coats, both versions of the tailcoat: the dress coat and the riding coat. The dress coat was cut in at the waist, either straight across or in an inverted U-shape (Figs. 1, 5). The riding coat, a less formal choice, sloped gently from the waist back to the tails (Fig. 6). Either style was made of fine, felted wool, which could be molded to the body, in dark colors such as blue, black, brown, red, and green (Byrde 91). The felted quality of the material allowed it to be cut with raw edges, and the high collar sloped down into lapels cut with either an “M” or “V” shaped notch (Davidson 28). Waistcoats were single-breasted and cut straight across the waist, peeking out beneath the closed coat. They featured stand collars and could be made of a variety of materials, solid or patterned; indeed, most of the color left in men’s clothing retreated to the waistcoat (Fig. 7) (Tortora 321; Davidson 28-29). It was also not unusual to wear two waistcoats at a time (Byrde 94).

Both breeches and pantaloons were worn, both featuring fall-front openings (Waugh 116). Breeches extended to the knee where they were fastened with buttons and a buckle or tie (Fig. 6); pantaloons, which had originated in the 1790s, were very tightly-fitted and longer, extending to the calf or ankle where they fastened with ties or buttons (Fig. 8). Either were appropriate in the daytime, but for evening wear, cream breeches paired with a black or blue dress coat, white waistcoat, and stockings were considered correct (Byrde 93; Johnston 14). As mentioned above, breeches or pantaloons with tall boots was a favorite fashion of the era, and lent civilian dress a martial allure (le Bourhis 112; Ashelford 186). Finally, during the 1800s, trousers gained some acceptance as an informal choice. While still narrow, trousers were looser-fitting than pantaloons at the calf and ankle, and they had been present in dress as a young boy’s garment and wear for sailors. They began to slowly be accepted as informal wear, especially at the seaside (Davidson 258-259; Foster 28; Byrde 93).

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (British). Fashion Plate: "Full dress and Morning Riding dress" for "Le Beau Monde", December 1801. Hand-colored etching. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, E.3123-1888. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (Probably British). Waistcoat (Vest), 1800-1810. Silk, linen, metal. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.2841. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 8 - Sir Henry Raeburn (Scottish, 1756-1823). Lieut-Colonel Bryce McMurdo, ca. 1800-1810. Oil on canvas; 240 x 148 cm. London: The Tate, N01435. Bequeathed by Gen. Sir Montagu McMurdo 1895. Source: ArtUK

Several pieces completed the male ensemble. Shirts were of white cotton or linen with very high stand collars that skimmed the jaw. Frills decorated the front of the shirt; after 1806, some shirts for daywear instead featured pleated fronts (Tortora 319; Byrde 94). Neckwear was a crucial element of a man’s wardrobe. The main form was the cravat, a large square of fine muslin or silk, folded cornerwise and carefully tied in a variety of arrangements (Fig. 3) (Waugh 119). Properly wrapping and tying the cravat was a principle concern of well-dressed men, and several manuals were available to consult for the correct method (Byrde 94). A hallmark of early nineteenth-century menswear was the dangling seals and fobs at the waist, which were attached to the watch tucked into a pocket in the waistband (Figs. 1, 5, 6) (Ashelford 186; Cumming 83). The top hat was now the dominant form of headwear. It was made in a variety of shapes, usually in felt; although the silk top hat began to be seen around 1803, it was not perfected until the 1830s (Ginsburg 85-86; le Bourhis 112-113). The eighteenth-century bicorne, a hat with a turned-up brim creating two points, was still seen (Fig. 6). It was especially fashionable in the evening, carried under the arm, for which occasions it was known as a chapeau bras (Tortora 322; Davidson 200, 226).

CHILDREN’S WEAR

Infants were dressed in long, back-fastening dresses featuring a low neckline and short sleeves, and a simple baby cap (Fig. 1) (Buck 46, 50). White cotton was the usual material as it allowed for easy laundering. Particularly fine examples could feature whitework and drawn-work embroidery (Rose 29). When a baby reached about six months old, the gowns shortened to calf-length to allow movement (Callahan). As toddlers, boys and girls were dressed in similar clothes. Both wore calf-length dresses, often called frocks. Very small children, up to age two or three, could be seen without any leg coverings under these frocks (Fig. 2). After that age, boys wore trousers under their frocks; girls did as well but since their hemlines descended to ankle-length, it was harder to discern their trousers, or drawers as they would later be called (P. Cunnington 161; Buck 109). Similar to womenswear, toddler dresses usually featured low, square necklines, puffed sleeves, and a very high waistline (Buck 66, 106; Ashelford 280-281).

Fig. 1 - John Russell (British, 1745-1806). Mrs. Robert Shurlock (Henrietta Ann Jane Russell, 1775-1849) and Her Daughter, Ann, 1801. Pastel on paper, laid down on canvas; 60.6 x 45.1 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 67.132. Gift of Geoffrey Shurlock, 1967. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown (British). Fashion Plate: "Mourning dress" for "Ackermann's Repository", September 1, 1809. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met Digital Collections

Fig. 3 - Samuel Woodforde (English, 1763-1817). The Bennett Family, 1803. Oil on canvas; 119 x 143 cm. London: The Tate, T02207. Presented by the Rev. Gerald C. Streatfeild 1977. Source: The Tate

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (Danish). Girl's dress, back view, 1800-1810. Printed cotton. Copenhagen, Denmark: The National Museum, 414/1942. Source: The National Museum

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (English). Skeleton suit, ca. 1800-1805. Nankeen. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.165&A-1915. Given by Miss E. Marian Adeney. Source: The Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 6 - Jens Juel (Danish, 1745-1802). A Running Boy, Marcus Holst von Schmidten, 1802. Oil on canvas; 180.5 x 126 cm. Copenhagen, Denmark: State Museum of Art, KMS3635. Acquired, 1923. Source: Wikimedia

Girls’ clothing and womenswear were closely related. Throughout their childhood and adolescence, girls wore dresses much like their mother’s (Fig. 3). During the 1800s, even young girls wore their hemlines long to the ankles; it was only in later years that girls’ hemlines began to climb. As the silhouette narrowed, girls could dispense with layers of petticoats, instead wearing just one. Drawers were increasingly worn, but the long skirts hid these bifurcated garments from view (P. Cunnington 194-197; Buck 106, 211). Dresses for morning wear were often of a printed cotton (Fig. 4), but afternoon or best dresses were in fine white muslin. The wide waist sash of the previous decade had disappeared in womenswear, but remained an important element of a girl’s outfit (Rose 38-41; Buck 203-204, 208). Outerwear was important for girls as the short-sleeves and low necklines of fashionable dress offered little protection. A common form was the tippet, a small cape which was often made to match the dress. The spencer was also worn. Finally, a girl completed her outfit with headwear similar to adult fashions (Buck 212-217; Rose 43). By sixteen years of age, a girl was considered a young woman, lowering her hem all the way to the floor (P. Cunnington 194).

Boys passed through roughly three stages of dress, beginning with the frocks of toddlerhood, discussed above. Then, at about age three or four, a boy was breeched, a rite of passage in which he received his first trousers. These were an element of the skeleton suit, a garment that originated in the 1780s (Fig. 5). It consisted of loose trousers buttoned onto a very short jacket, completed with a white shirt featuring an open collar (Fig. 3) (Callahan). During the 1800s, the skeleton suit was made in strong cotton or linen, and the jacket and trousers could be of contrasting colors (Buck 111; Rose 51). A boy remained in the skeleton suit until about age ten; a transitional variation was sometimes worn by older boys in which the short jacket was worn outside the trousers. Then, from age ten through their early teenage years, boys wore short, round jackets and waistcoats with closer-fitting trousers or pantaloons. Sometimes the jacket had shortened, squared tails in the back (Fig. 6). By fifteen, a boy made the full transition to men’s styles, switching the open collar for a cravat and donning adult tailcoats and breeches (Buck 194-196; P. Cunnington 172-175; Callahan).

References:

- Ashelford, Jane. The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society, 1500-1914. London: National Trust, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/243850605

- Buck, Anne. Clothes and the Child: A Handbook of Children’s Dress in England, 1500-1900. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/243852072

- Byrde, Penelope. Nineteenth Century Fashion. London: Batsford, 1992. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/26300526

- Callahan, Colleen R. “Children’s Clothing.” in The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 145-149. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Bloomsbury Fashion Central via the New York Public Library. http://dx.doi.org.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0003223.

- Cicolini, Alice. “Dandyism.” in The Berg Companion to Fashion. Edited by Valerie Steele, 199-204. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Bloomsbury Fashion Central via The New York Public Library. http://dx.doi.org.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0004454

- Cunnington, C. Willett. English Women’s Clothing in the Nineteenth Century: A Comprehensive Guide with 1,117 Illustrations. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868281120

- Cunnington, Phillis, and Anne Buck. Children’s Costume in England: From the Fourteenth to the end of the Nineteenth Century. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1978. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/174334043

- Cumming, Valerie ed., The Dictionary of Fashion History. New York: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1003643284

- David, Alison Matthews. “Brummell, George (Beau)*.” in The Berg Companion to Fashion. Edited by Valerie Steele, 103-105. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Bloomsbury Fashion Central via The New York Public Library. http://dx.doi.org.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0002469

- Davidson, Hilary. Dress in the Age of Jane Austen: Regency Fashion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1115106379

- Foster, Vanda. A Visual History of Costume: The Nineteenth Century. London: BT Batsford, 1984. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/28405843

- Fukai, Akiko, ed. The Collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute: Fashion, A History from the 18th Century to the 20th Century. Kyoto: Taschen, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/81452017

- Ginsburg, Madeliene. The Hat: Trends and Traditions. London: Studio Editions, 1990. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/22914760

- Jensen, Heather Belnap. “Parures, Pashminas, and Portraiture, or, How Joséphine Bonaparte Fashioned the Napoleonic Empire.” in Fashion in European Art: Dress and Identity, Politics and the Body, 1775– 1925. Edited by Justine De Young, 36-59. London/New York: I.B.Tauris, 2017. Bloomsbury Fashion Central via The New York Public Library. http://dx.doi.org.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/10.5040/9781350986381.ch-002

- Johnston, Lucy, Marion Kite, Helen Persson, Richard Davis, and Leonie Davis. Nineteenth Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publications, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/61302743

- Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/966352776

- le Bourhis, Katell, ed. The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire 1789-1815. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/60131971

- Marschner, Joanna. “Court Dress.” in The Berg Companion to Fashion. Edited by Valerie Steele, 182-184. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Bloomsbury Fashion Central via The New York Public Library. http://dx.doi.org.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0004011

- Rose, Clare. Children’s Clothes: 1750-1985. London: BT Batsford, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/317672212

- Ribeiro, Aileen. Fashion in the French Revolution. London: Batsford, 1988. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/925254276

- Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865480300

- Waugh, Norah. The Cut of Men’s Clothes: 1600-1900. New York and London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927414537

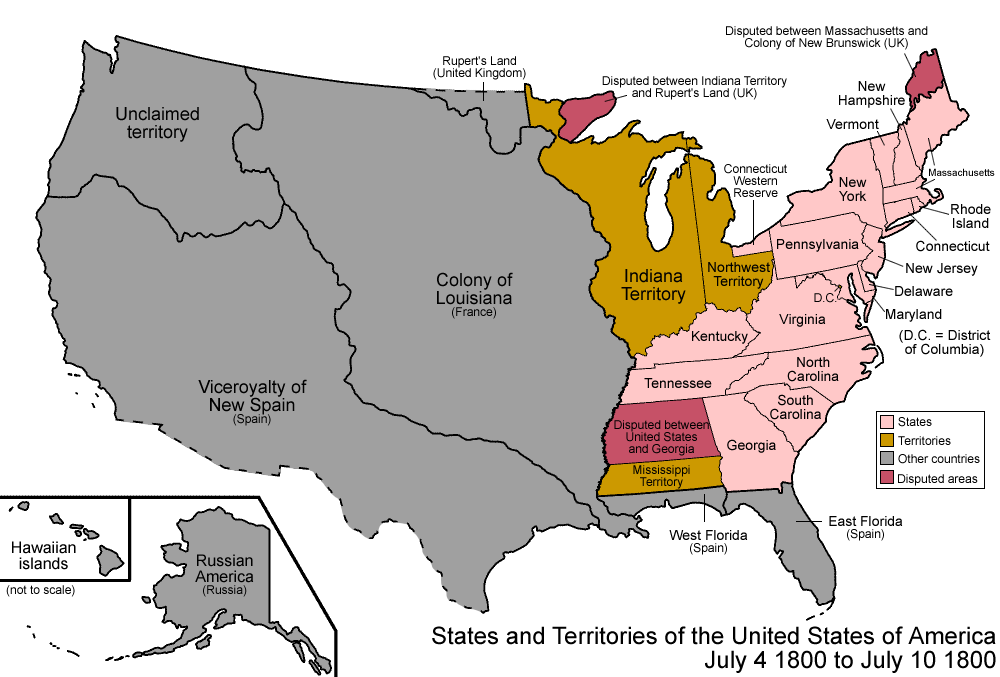

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1800-1809

Rulers:

- England: George III (1760-1820)

- France

- First Republic (1792-1804)

- Emperor Napoleon I (1804-1814)

- Spain: Charles IV (1748-1819)

- United States

- John Adams (1797-1801)

- Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809)

Events:

- 1800 – The Act of Union annexes Ireland on May 5, creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

- 1800 – Washington D.C. is established as the capital of the United States.

- 1803 – The United States purchased the Louisiana Territory from France.

- 1804 – Napoleon becomes Emperor. During his reign, he puts France at the forefront of fashion innovation and design.

- 1804 – Joseph Marie Jacquard invents the jacquard loom, which used punch cards to create complex designs.

- 1805 – The Battle of Trafalgar delivers a decisive victory to Great Britain in the Napoleonic Wars, and established British naval superiority for decades.

- 1808 – John Heathcoat patents a bobbin-net machine, allowing net to be manufactured much more affordably.

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Fashion Plate Collections (Digitized)

- Costume Institute Fashion Plate collection

- Casey Fashion Plates (LA Public Library) - search for the year that interests you

NYC-Area Special Collections of Fashion Periodicals/Plates

- FIT Special Collections (to make an appointment, click here)

- Costume Institute/Watson Library @ the Met (register here)

- New York Public Library

- Brooklyn Museum Library (email for access)

Fashion Periodicals (Digitized)

Etiquette Books (Digitized)

Secondary Sources

Also see the 19th-century overview page for more research sources... or browse our Zotero library.