Elsa Schiaparelli created this unusual lobster dress with the help of Surrealist artist Salvador Dali in 1937, demonstrating the interconnected nature of the fashion and art worlds in the early 20th century.

About the Look

T

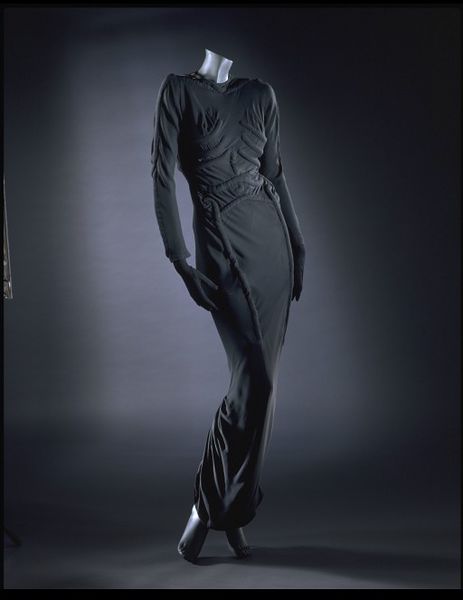

his dress by Italian fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli was a unusual garment for its time. Schiaparelli drew on her friendship with Spanish artist Salvador Dalí to create this in 1937 in the midst of the Surrealist art movement.

His work inspired the lobster design, and he drew the initial motif that was then incorporated onto the fabric. The lobster art was printed onto the silk organza dress by master silk designer Sache (Fig. 1) (Blum 135).

The dress is an off-white, A-line evening gown with a sheer coral inset below the bust that creates a slight empire-waist silhouette.

Fig. 1 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890-1973). Woman's Dinner dress, February 1937. Printed silk organza and synthetic horsehair. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1969-232-52. Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli, 1969. Source: PMA

Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890-1973). Woman’s Dinner Dress, February 1937. Printed silk organza and synthetic horsehair. Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1969-232-52. Gift of Mme Elsa Schiaparelli, 1969. Source: PMA

About the context

Elsa Schiaparelli designed avant-garde gowns from the 1920s until her couture house closed in 1954, and is most famous for her work in the 1930s. She was born to an academic family in Rome in 1890, and the thought that she would go into a creative career was unimaginable to them (Baxter-Wright 9).

In The History of Modern Fashion from 1850 (2015), Daniel James Cole and Nancy Deihl deem Schiaparelli one of the great designers of the 1930s. Many of her fashion contributions included collaborations with several Surrealist artists with results similar to this stand-out gown. Dali had incredible enthusiasm for fashion:

“Dalí’s increasingly commercial endeavors and lifelong interest in dress led him to become hugely influential in fashion, from his meticulously flamboyant self-presentation to his collaborations with couturières, to the clothing, jewelry, and store window displays that he went on to create.” (Moyse abstract)

This love of and influence in the fashion industry is what brought these two Thirties greats together, and the ‘lobster dress’ is enduring evidence of their friendship. In her The Little Book of Schiaparelli (2012), Emma Baxter-Wright explains:

“The partnership was rewarding for both artists, as Schiaparelli was known for her love of shock tactics and for her willingness to challenge the conventions of beauty and gender stereotypes.” (73)

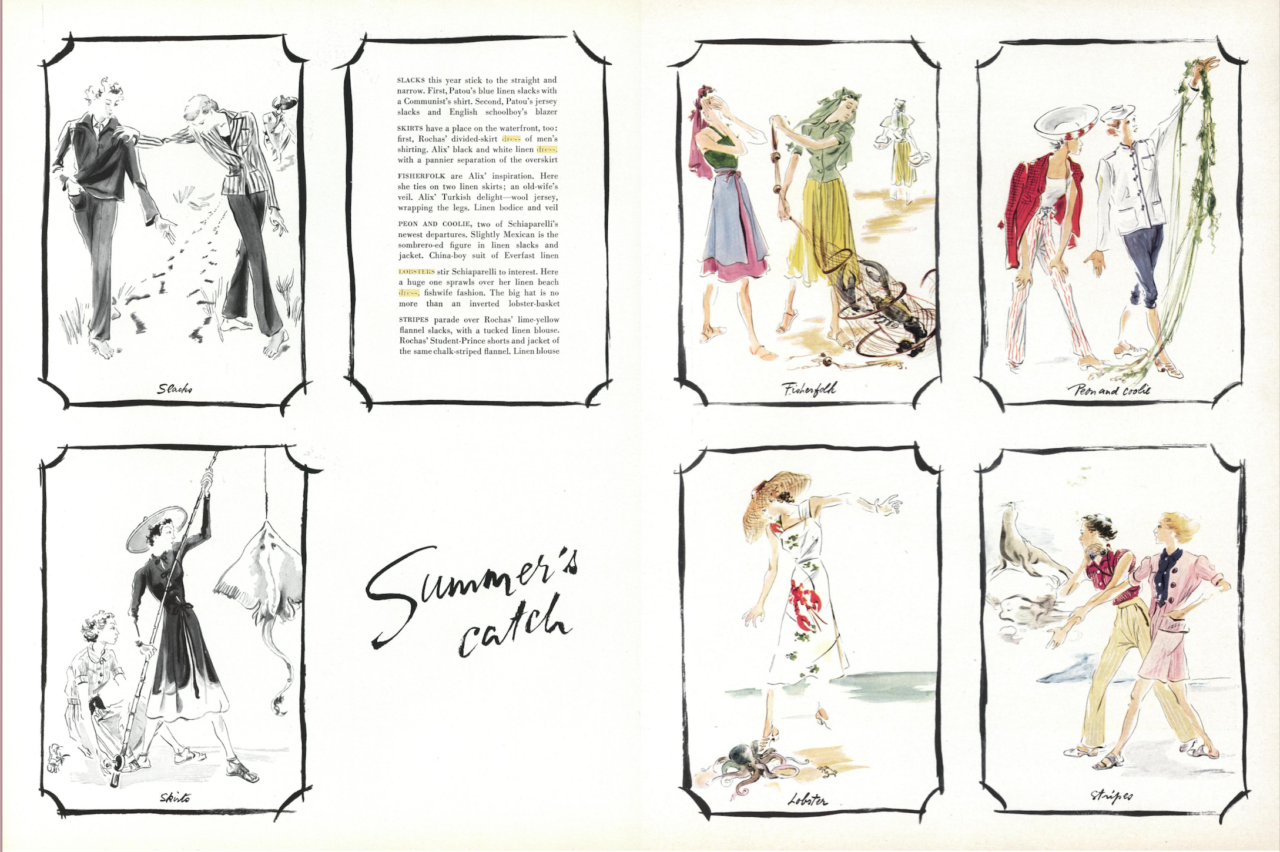

The two would go on to create several other garments together, like the 1937-38 “Shoe Hat” and 1938’s “Skeleton Dress” (Figs. 2 & 3). See also a series of sketches from Schiaparelli that appeared in Vogue 1937 that includes this famous dress, simply titled ‘Lobster’ (Fig. 4), at the bottom center.

Fig. 2 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890-1973). Shoe Hat, 1937-38. Wool felt and silk velvet; length: 32 cm, height: 26 cm. Londom: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.2-2009. Source: VAM

Fig. 3 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890-1973). Skeleton dress, 1938. Silk crêpe, trapunto quilting, and cotton wadding. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.394&A-1974. Given by Miss Ruth Ford. Source: VAM

Fig. 4 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890-1973). "Fashion: Summer's Catch", Vogue (NY), Vol. 89, Iss. 10, (May 15, 1937): 86, 87. Source: ProQuest

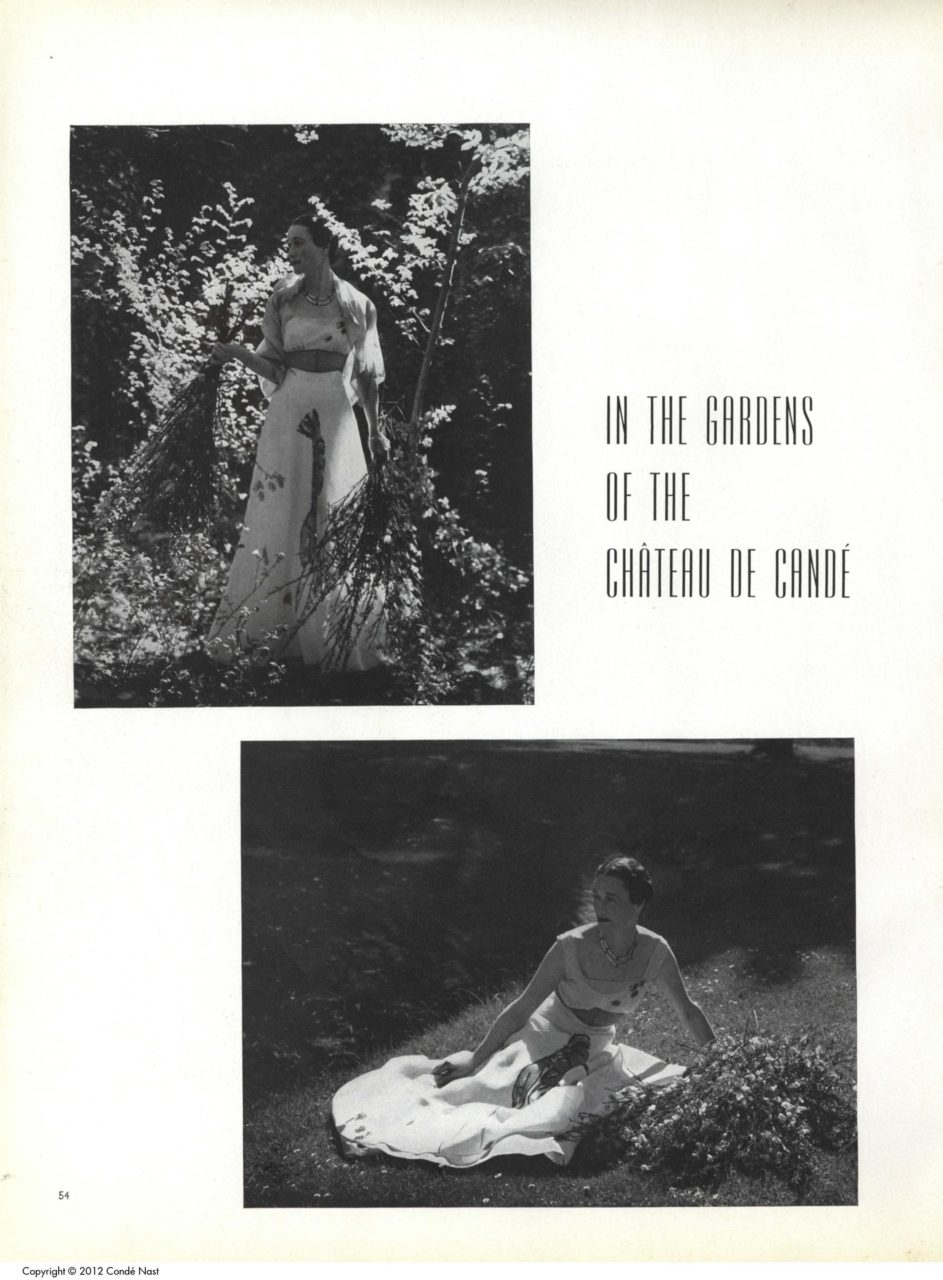

Just as Dali took inspiration from Schiaparelli’s fashion, she looked to his older work to inspire new art. The lobster motif came from a theme that Dalí had previously cultivated in his own work, which included 1936’s Lobster Telephone, and was influenced by the work of Sigmund Freud (Fig. 5). Schiaparelli’s dress attained widespread notoriety after Cecil Beaton photographed it on the American socialite Wallis Simpson; Simpson had recently gained the title Duchess of Windsor after Edward VIII abdicated the British throne in favor of marrying her (Fig. 6). In the exhibition catalogue for Shocking! The Art and Fashion of Elsa Schiaparelli, Dilys Blum writes: “Beaton took almost a hundred photographs during the session with Simpson, and Vogue devoted an eight-page spread to the results.” One page featured two photographs of Simpson in the Lobster dress in the gardens of the Château de Condé (Fig. 7).

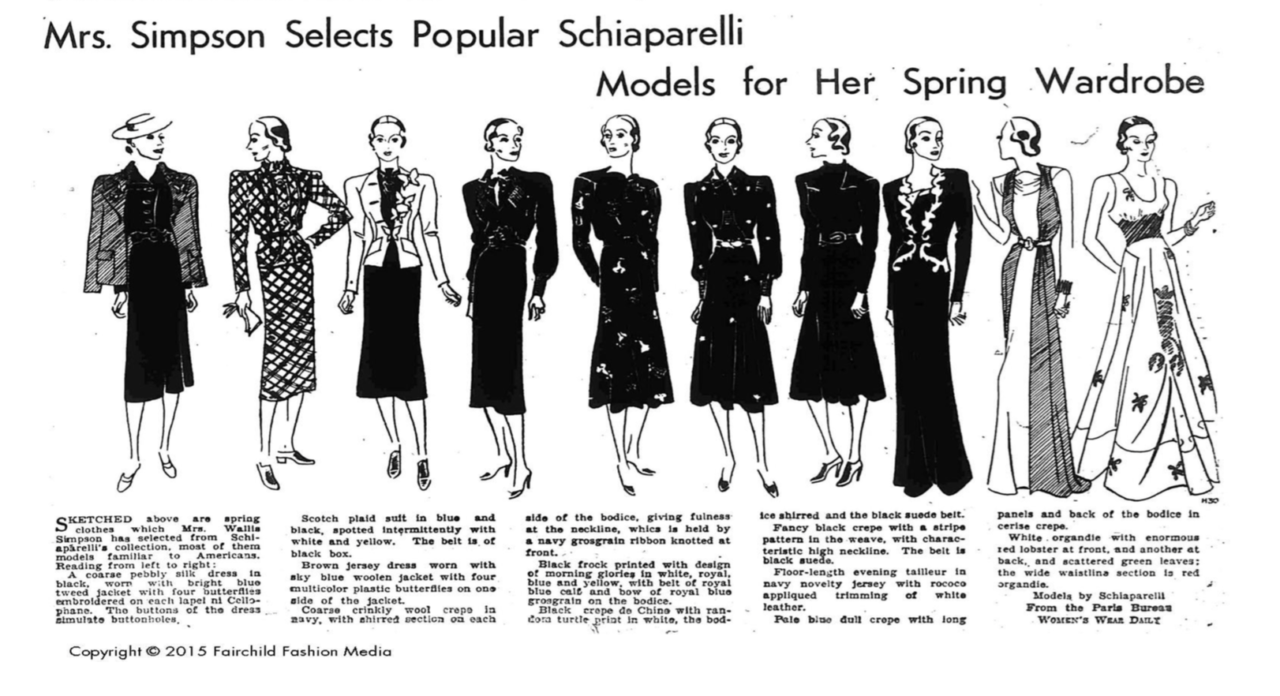

Women’s Wear Daily dedicated an article of its own to the garments Wallis Simpson selected to purchase from Elsa Schiaparelli’s collection, which includes the Lobster dress at far right (Fig. 8).

While Wallis Simpson brought in significant media coverage, the dress turned heads on its own. In The Little Book of Schiaparelli, Emma Baxter-Wright describes that “Dali’s famous lobster print appeared as the focus of attention, positioned provocatively on a simple white evening dress with little other decoration to distract” (74). Lucy Moyse notes: “According to Schiaparelli, Dali was disappointed that she did not allow him to add a final surreal flourish to the finished gown–mayonnaise” (56).

While Schiaparelli’s dress is not typical of 1930s fashion, it does fit some general aspects of contemporary style. Cole and Deihl discuss how “Neoclassical styles were the prevailing mode early in the decade; white and ivory columnar bias cut evening dresses” were popular, along with asymmetry, but “later in the decade, bold graphic trims were applied, and symmetry was once again common” (163-4). And indeed – despite its Surrealist deviation, the lobster dress is ivory, has hints of an empire waist, some splashes of bold color, and an asymmetrical graphic. In an article in Women’s Wear Daily from February 1937, a ‘Madame Zigmund’ is quoted in regards to Paris Fashion Week: “Everyone showed dresses with wide skirts for evening” and she found them especially attractive. Just so – the lobster dress, despite Empire-style roots, has a full, bias-cut hemline that increases its width.

Fig. 5 - Salvador Dali (Spanish, 1904-1989). Lobster Telephone, 1936. Steel, plaster, rubber, resin, and paper; 17.8 × 33 × 17.8 cm (7 × 13 × 7 in). London: Tate, T03257. Purchased at Christie's (Grant-in-Aid) 1981. Source: Tate

Fig. 6 - Cecil Beaton (British, 1904-1980). Wallis Simpson, 1937. Photograph. Getty Images. Source: Vogue

Fig. 7 - "The Future Duchess of Windsor". Vogue (NY), Vol. 89, Iss. 11, (Jun 1, 1937): 54. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 8 - "Mrs. Simpson Selects Popular Schiaparelli Models For Her Spring Wardrobe". Women's Wear Daily, Vol. 54, Iss. 87, (May 5, 1937): 3. From the Paris Bureau Women's Wear Daily. Source: ProQuest

Its Afterlife

The lobster dress has made several famous reappearances in the 21st century. A structured-looking column gown with a beaded lobster across its side was made by Prada for Anna Wintour; it was specifically for the 2012 Met Gala, which had the theme of “Schiaparelli and Prada: Impossible Conversations” (Fig. 9). Bias-cut gowns experienced a resurgence in popularity in the early 2000s, but by 2010 the fashion was for minimalist, structured gowns; this seems like an appropriate update.

Another notable recreation came in 2017; the House of Schiaparelli’s then-creative director, Bertrand Guyon, designed a throwback for the Spring 2017 couture collection (Fig. 10). The dress, released on the 80-year anniversary of the original garment, is another column-shaped rendition of the original, but with soft draping and asymmetry that Schiaparelli would hopefully have approved of. Its lobster is just as soft and surreal as the original, but made of appliqué, and it occupies the same pride of place on the skirt.

Fig. 9 - Miuccia Prada (Italian, 1949-). Lobster dress, May 2012. Getty Images. Source: Time

Fig. 10 - Bertrand Guyon for Elsa Schiaparelli (French, 1966-). Lobster dress, February 2017. Photo: Indigitial.tv. Source: Vogue

References:

- Baxter-Wright, Emma, and Elsa Schiaparelli. The Little Book of Schiaparelli. London: Carlton Books, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/990373640.

- Blum, Dilys E. Shocking! The Art and Fashion of Elsa Schiaparelli. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/52381172

- Cole, Daniel James, and Nancy Deihl. The History of Modern Fashion from 1850. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/932219920.

- “Features: The Future Duchess of Windsor.” Vogue, Jun 01, 1937, 52-52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879209111?accountid=27253.

- “Mme. Zigmund Impressed with Many Novelties.” Women’s Wear Daily 54, no. 33 (February 17, 1937): 7. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1653750370?accountid=27253.

- “Romance, Fun, Gaiety in Today’s Paris Openings.” Women’s Wear Daily 54, no. 24 (February 4, 1937): 4. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1653747349?accountid=27253