Angiola di Bernardo Sapiti and Lorenzo di Ranieri Scolari dress in keeping with 1440s Florentine fashions.

About the Portrait

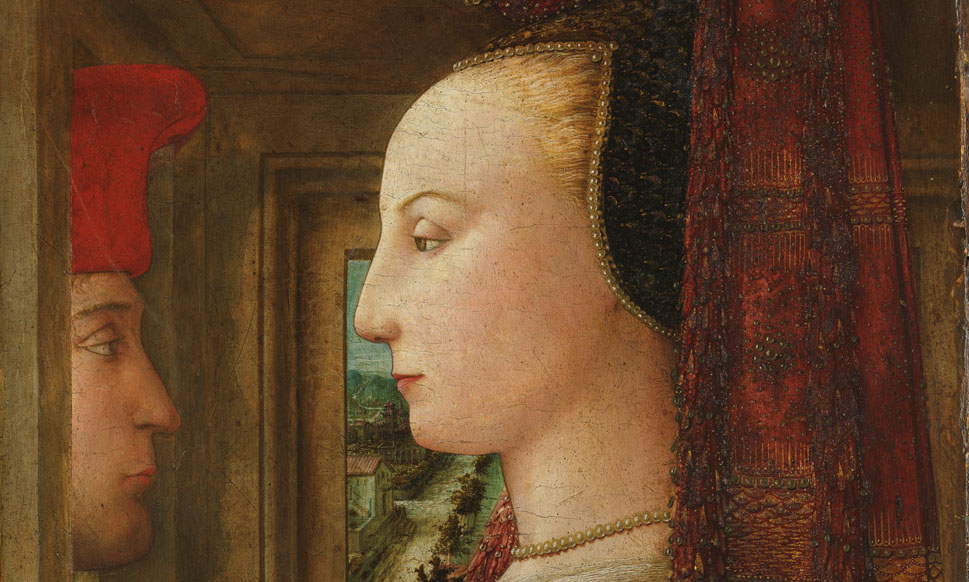

Fra Filippo Lippi was an Italian Renaissance painter born c. 1406. In a 1438 letter from Domenico Veneziano to Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici Lippi was said to have become, alongside Fra Angelico, one of the two most coveted painters in Florence (Oxford Art Online). Since the Portrait of a Woman with a Man at a Casement is from 1440, the painting was created when he was well-established as an artist. As the Met notes, this is the earliest double portrait from Italy that survives and also the first that displays the sitters in a home and to include a landscape view. It was popular to be painted in profile among Italians of the time. The sitters are likely to be Lorenzo di Ranieri Scolari and Angiola di Bernardo Sapiti. Lorenzo is seen with his hand upon his coat of arms. The Met goes on to explain that their relationship is told via the portrait since the lettering on Angiola’s sleeve spells “lealta,” which is Italian for “faithful.” The two were married c. 1439. It is possible that the piece was commissioned either for the celebration of the birth of a child or, more likely, to commemorate their marriage as her jewelry alludes to. Though exact ages are unknown, it was common place for women to be wed as teenagers (The Met).

Fra Filippo Lippi (Italian, Florence ca. 1406–1469). Portrait of a Woman with a Man at a Casement, 1440. Tempera on wood; 64.1 x 41.9 cm (25 1/4 x 16 1/2 in.). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand 1889. 89.15.19. Source: The Met

About the Fashion

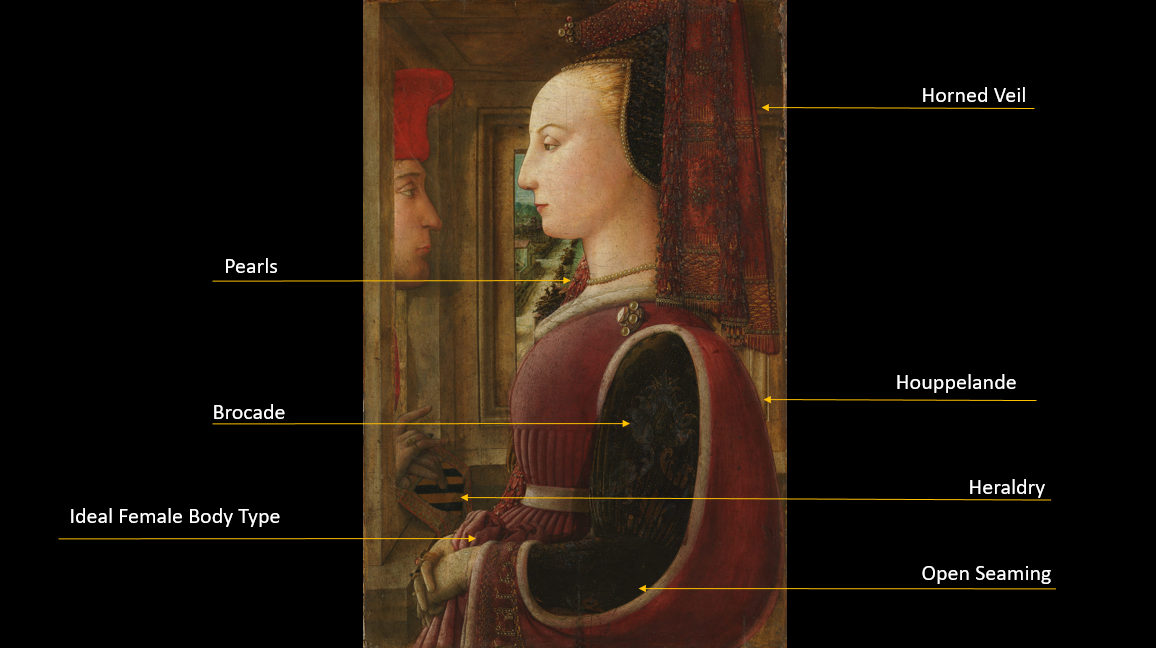

The sitter is wearing a typical 15th century garment known as the houppelande. This is an outer tunic with vertical pleats or folds at the front and back of the garment. Her houppelande is complete with open seaming which was also common at the time; this occurs when the seams of the sleeves are left open and are not stitched in order to display the undersleeve as a sign of wealth. She is portrayed wearing an even more lavish look due to the fact that her undersleeve is made of a luxurious brocade fabric, which was fashionable and much sought after during the 15th century.

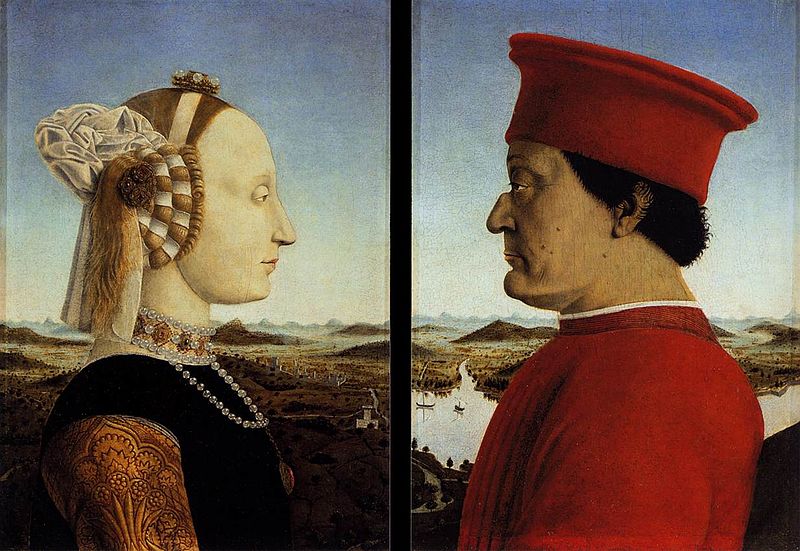

Van der Weyden’s Portrait of Isabella of Portugal (Fig. 1) depicts womenswear of a comparable time as the portrait is circa 1450. Isabella is wearing a brocaded fabric proving the fashionable state of this style. Isabella is also wearing a headdress and pearls while possessing the ideal female body type discussed later. Figure 2 displays an image of Piero della Francesca’s Ritratto di Battista Sforza e Federico da Montefeltro in which a very similar brocaded sleeve can be seen.

Fashion historian Daniel Delis Hill explains in The History of World Costume and Fashion (2011) that the sitter’s horned veil was a way to signify marital status. Unmarried women kept their hair natural and flowing. Married women, on the other hand, wore styles such as braids, knots, and buns. These hairstyles often had ribbons, pearls, chains, and veils such as the one depicted here (Hill 353).

Figure 3 displays a work by Jan van Eyck, the Portrait of Margaret van Eyck, from the year 1439. The striking similarities continue with this comparison image due to Margaret’s veil/head covering style, houppelande, and body type highlighted.

Another key identifier that has been alluded to previously is that the sitter possesses the ideal female body type for 15th century: a short-waisted silhouette, belted under the breast, with a protruding abdomen. Hill writes of this silhouette:

“The fullness of the bodice was gathered or pleated under a girdle that set above the natural waistline. This short-waisted silhouette emphasized the preeminent element of feminine beauty of the time, the protuberant abdomen. To achieve this pregnant profile, women even inserted bags of padding under their gowns. But the look ‘connoted elegance rather than fruitfulness’ suggests art historian Anne Hollander.” (337-38)

Van Eyck’s 1434 piece, the Arnolfini Portrait (Fig. 4), captures a clear example of the idealized female body discussed. The woman is also shown wearing a vertically pleated houppelande and a veil signifying marital status. Ercole de’ Roberti’s Portrait of Ginevra Bentivoglio (Fig. 5) highlights key 15th century womenswear components as well. Ginevra again has the ideal body clearly shown in her profile, a veiling of sorts, and is wearing pearls around her neck.

The sitter is wearing pearls, a jewel-encrusted broach, and many rings at once (some higher up on the finger) adding to her wealthy stature and fashionable state as well.

Margot Lister in Costume An Illustrated Survey from Ancient Times to the 20th Century (1972) lists the common fabrics employed in the 15th century:

“Wool of all grades, some cotton, linen of various qualities, satin, velvet, taffetas, rich silks in plain colours or embroidered, cloth of gold, silver and gold tissue, brocade and damask, with every type of fine lawn, gauze or thin silk for veils and headdresses.” (152)

In this case, the female sitter is likely wearing a fur-lined velvet houppelande. Her sleeve is almost certainly a brocaded velvet since this was commonplace of the time.

As for the man in the background, not much of his garments are visible, but we can easily notice the heraldry beneath his hands. Heraldry originated in the Late Middle Ages with the invention of chainmail; an identification problem arose at battle and so knights began carrying symbols as a way to denote what side they were on. Heraldry continued to be utilized even after the disappearance of chainmail to mark family lineage. Art historian Paola Tinagli explains in her work Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation and Identity (2015) that the man is wearing a hat known as a berretta alla capitanesca which is often red and simple in style (Tinagli 52).

Piero della Francesca’s Ritratto di Battista Sforza e Federico da Montefeltro (Fig. 2) also verifies that the berretta alla capitanesca was a popular 15th century hat silhouette for men.

Fig. 1 - Rogier van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1399/1400 - 1464). Portrait of Isabella of Portugal, 1450. Oil on panel; 46 × 37.1 cm (18 1/8 × 14 5/8 in). Los Angeles: The Getty Museum. Source: The Getty Museum

Fig. 2 - Piero della Francesca (Italian, 1420-1492). Ritratto di Battista Sforza e Federico da Montefeltro, ca. 1465. Tempera on panel; 47 × 33 cm (18.5 × 13 in). Florence: Uffizi Gallery, 3342,1615. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 3 - Jan van Eyck (Dutch, 1422-1441). Portrait of Margaret van Eyck, 1439. Oil on wood; 25 x 32.6 cm (9.8 x 12.8 in). Private Collection. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 4 - Jan van Eyck (Dutch, 1422-1441). The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434. Oil on oak; 82.2 x 60 cm (32.36 x 23.62 in). London: The National Gallery. Source: The National Gallery

Fig. 5 - Ercole de' Roberti (Italian, 1455/1456 - 1496). Portrait of Ginevra Bentivoglio, 1474/1477. Tempera on poplar panel; 53.7 x 38.7 cm (21 1/8 x 15 1/4 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1939.1.220. Source: National Gallery of Art

Diagram of referenced dress features. Source: Author

References:

- “Fra Filippo Lippi | Portrait of a Woman with a Man at a Casement | The Met.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Accessed November 3, 2017. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436896.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/731445106

- Lister, Margot. Costume: An Illustrated Survey from Ancient Times to the Twentieth Century. Boston: Plays, Inc, 1993. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/493187

- and . “Lippi.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed November 3, 2017, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T051269pg1.

- Tinagli, Paola. Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation and Identity. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/986609380.

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Sara B. Marcketti. Survey of Historic Costume. Sixth edition. New York: Fairchild Books, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/39609620