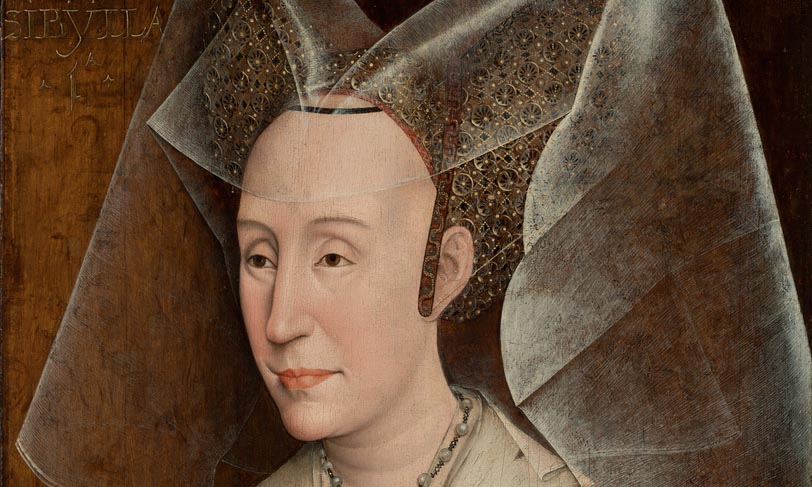

Isabella of Portugal, Duchess of Burgundy, painted by Rogier van der Weyden in 1450, is depicted wearing the latest styles of the Burgundian nobility.

About the Portrait

R

ogier van der Weyden was born in Tournai, present day Belgium, somewhere between 1399/1400 to 1464 (Clarke 44). Although little is known about the Netherlandish painter due to the lack of sources on his time, he mainly produced works comprising of religious triptychs, altarpieces and diptych portraits commissioned from, among others, Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, Netherlandish nobility and other foreign princes (Campbell 9).

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. Portraits of Philip the Good and Isabella of Portugal, 16th Century. Oil on panel; 21.7 × 28.7 cm (8.5 × 11.3 in). Ghent: Museum of Fine Arts, S-98. Source: Wikimedia Commons

According to art historian Erwin Panofsky, van der Weyden began his painting career at the age of 27 when he enrolled as an apprentice in the workshop of Robert Campin. After this apprenticeship, he was named master of the Tournai Guild of St. Luke. He then moved to Brussels in 1435 where he quickly established his reputation for his technical skill and emotional use of line and color (Panofsky 246).

Van der Weyden painted Isabella of Portugal’s portrait circa 1450, at a time when he was already a renowned artist and was producing altarpieces and portraits for Europe’s nobility (Campbell and Périer-d’Ieteren).

The sitter in this portrait is Isabella of Portugal, Duchess of Burgundy. Isabella was born in Evora, Portugal in 1397 to King John I of Portugal and Philippa of Lancaster. Isabella became the third wife of Philip the Good, the reigning Duke of Burgundy, in 1429 (Fig. 1) (Taylor). From 1441, the court of the Burgundy aristocracy was based in Brussels, where van der Weyden lived at the time.

This portrait was commissioned by Isabella’s husband, Philip the Good, to Rogier van der Weyden in 1450. It is known Philip had already commissioned other works from van der Weyden, including portraits of himself, his son Charles, and other members of the court.

Due to the fact that van der Weyden ran a workshop, the task of attributing artworks to him and/or his assistants is difficult and unclear, and such is the case in this portrait (Campbell and Périer-d’Ieteren, Grove). There are some sources that claim this portrait was done by van der Weyden himself, while other sources, like the J. Paul Getty Museum, claim it was done by a member of his workshop who copied Isabella’s likeness from a lost portrait by van der Weyden (The Getty). Some of the arguments say that although there are some typical van der Weyden style elements in the portrait (like the elongated fingers and the slightly mocking facial expression), other elements like the upper right inscription PERSICA SIBYLLA IA, suggest the portrait may have been one of a series of portraits depicting sibyls. As, according to The Getty,: “this identity strikingly contrasts with Duchess Isabella’s costume” it suggests that “someone other than the original artist added the inscription, as well as the brown background meant to simulate wood, some time after the portrait was painted” (The Getty). The Getty also affirms that “the duchess never actually sat for this portrait, which may account for the misunderstood representation of her clothing” (The Getty).

Van der Weyden was one of the most celebrated portrait painters of the Burgundian court, and the way in which he depicted his sitters was very acclaimed and preferred by them. Van der Weyden’s “highly subjective attitude to his sitters, in which he imposes his own ideals on them, makes his portraits similar in conception to his religious paintings, where narrative interest is subordinated to van der Weyden’s own highly individual vision of his subject” (Campbell and Périer-d’Ieteren). Isabella of Portugal was painted by many different artists throughout her life (Figs. 4 and 5).

Workshop of Rogier van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1399/1400 – 1464). Portrait of Isabella of Portugal, ca. 1450. Oil on panel; 46 × 37.1 cm (18 1/8 × 14 5/8 in). Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, N203. Source: The Getty Museum

About the Fashion

Isabella of Portugal is depicted in this portrait wearing a V-neck gown, which was developed from the houppelande. A houppelande is a long, full pleated gown cut from large circular shapes, belted over a tight underdress that was buttoned or laced down the front worn at the beginning of the century years by noblewomen (Fig. 2) (Brown 74). From 1450-1500 the costume for women changes, as fashion historian Blanche Payne explains in History of Costume: from the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century (1965):

“The neckline of women’s cottes and surcoats, which has been wide and low in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, was modified to a deep V-shape mid-century gown, the décolletage being filled in with a stomacher or by an underdress. Trains dominated skirts throughout the century, though the round-length—a skirt of even length without a train – was introduced at the court of Burgundy about 1460, and sleeves became long and closely fitted.” (235)

The V-neck gowns predominate over the houppelandes, changing the silhouette of women’s costume, and making the fit to became less full, and the bodice to have a closer fit, the belt widens and the sleeves became more modest and tubular. As we can see in this Rogier van der Weyden painting from ca. 1438 (Fig. 3), the gown somewhat resembles the houppelande worn in previous years, like in this van Eyck’s 1434 portrait of a noble wedding (Fig. 2). Both gowns have similar colors, but the silhouette has evolved from fuller skirts to lower V-neck lines ones with lower pleating and the sleeves have gotten tighter (Brown 80). The belt underneath the bust remains in the V-neck gown, as the desirable quest for the protuberant stomach style continues (Figs. 2-6, 8, 9, 11).

Isabella’s costume in the portrait reflects this change exactly: her sleeves are flared and modest-sized, and her sharp V-neck is laced together at the front. Although her skirt is not entirely shown on the portrait, Isabella’s skirt was probably floor-length and had a long trail on the back, as this was the common look worn by nobility of the time (Fig. 8).

According to fashion historian François Boucher, Isabella influenced Burgundian costume immensely; he writes that she “brought in new fashions, while Italy, Spain and Germany sent their rare textiles, pleated linen and pinked gowns respectively” (203). As Payne notes: “Fashion influence spread from [the Burgundian] court the way it does from Paris today. Two women closely associated with these court fashions were Isabelle [sic] of Portugal, wife of Philip the Good, and Mary, daughter of Charles the Bold.” (Payne 242).

The style of her dress epitomizes the latest trend of the time, implying Isabella was at the forefront of fashion since she has updated the look from the houppelandes worn in previous years to the new more fitted, V-neck version. This new gown was very well received by Isabella, since she commonly portrayed wearing such style (Figs. 4 and 5). This trend was also worn by members of the nobility (Figs. 8, 9, 11), and by other female rulers of time, like Mary of Guelders, Queen of Scotland (Fig. 6), and Marguerite d’Orleans, Countess of Vertus (Fig. 7).

Burgundy was especially known for its flamboyant style. As Boucher recounts in 20,000 Years of Fashion (1987):

“The court of Burgundy surpassed all others in the richness of its costume: sumptuous textiles, varied embroidery, and an incessant renewal of garments. On the whole, Burgundian styles absorbed outside elements to recreate a costume of unparalleled individualism.” (202-203)

Led by the desire to equal the kings surrounding them, the Duke and Duchess of Burgundy, Philip the Good, and Isabella, spent a large part of their personal revenue on costume (Boucher 202). They were known for their “taste for richness, the use of luxurious, often foreign, cloths and silks, and the exaggerated head-dresses” which were very present and caused Burgundy to surpass France in style (Boucher 203).

During the late 15th century, sumptuary laws were still active and ineffectively regulating who wore what (Brown 74). Thus, every social class had its own rules and appearances assigned. Also during this time, there are a lot of changes in the structure of society. Of these changes, Boucher writes in 20,000 Years of Fashion (1987):

“The growth of towns and the enrichment of the mercantile classes led to the emergence everywhere of a rich bourgeois which aspired to the privileges of the nobility. Costume thus became a means for one class to demonstrate its rise, and for another to empathize its jealously guarded prominence.” (192-193).

As Isabella was already the Duchess of Burgandy when van der Weyden painted the portrait, she is represented wearing the most luxurious materials, and the typical costume worn by other noblewomen. Isabella is portrayed by van der Weyden wearing a luxurious attire, the V-neck gown was probably made out of silk velvet and it was heavily woven with gold thread. Silk velvet was extremely popular in this time and could be intricately cut to achieve the rich textures common in the Renaissance dress. Her gown is richly brocaded with gold, commonly used by other contemporary rulers in Europe (Figs. 1, 4-7).

The gown also has a fur lining, which was a sign of luxury and all elegant, costly garments of the time were trimmed with it as edging or lining (Figs. 2, 4-11) (Boucher 214). Isabella’s fur is ermine, the most expensive and highly regarded fur due to its rarity. Her belt is tablet-woven in silk, with gold ends, and is belted under the bust (Fig. 3). Colors during this time were attributed to distinctive occupations, and the Burgundy Parliament had very strict rules: only its members were allowed to wear black, red and violet (Boucher 201). Red was typically also used and reserved by all other European sovereigns during this time (Figs. 6, 8, 9, 11).

Fig. 2 - Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, ca. 1390-1441). Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife, ca. 1434. Oil on oak; 82.2 cm × 60 cm (32.4 in × 23.6 in). London: The National Gallery, NG186. Bought, 1842. Source: The National Gallery

Fig. 3 - Rogier van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1399/1400 - 1464). The Magdalen Reading, ca. 1438. Oil on mahogany, transferred from another panel; 62.2 x 54.4 cm (24.4 x 21.4 in). London: The National Gallery, NG654. Bought, 1860. Source: The National Gallery

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (Netherlandish). Portrait of a Noblewoman, Probably Isabella of Portugal, (1397–1472). Oil on wood; 34.6 x 27 cm (13 5/8 x 10 5/8 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 50.145.15. Bequest of Mary Stillman Harkness, 1950. Source: The Met

Fig. 5 - Petrus Christus (Netherlandish, ca. 1410/1420 – 1475/1476). Isabella of Portugal with St. Elizabeth, ca. 1457-60. Oak on panel; 59 x 33 cm (23.2 x 13 in). Bruges: Groeninge Museum. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 6 - Petrus Christus (Netherlandish, ca. 1410/1420–1475/1476). A Goldsmith in his Shop, 1449. Oil on oak panel; 100.1 x 85.8 cm (39 3/8 x 33 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.1.110. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975. Source: The Met

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown (French). Marguerite d'Orleans, Comtesse de Vertus, ca. 1430. Paris: Département des Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Source: Corpus Artistique Étampois

Fig. 8 - Petrus Christus (Netherlandish, ca. 1410/1420–1475/1476). Portrait of a Female Donor, ca. 1455. Oil on panel; 41.8 x 21.6 cm (16 7/16 x 8 1/2 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1961.9.11. Samuel H. Kress Collection. Source: National Gallery of Art

Fig. 9 - Rogier van der Weyden (Netherlandish, 1399/1400-1464). Seven Sacraments Altarpiece, ca. 1445-1450. Oil on oak panel; 200 x 97 cm (78.7 x 38.2 in). Antwerp: Royal Museum of Fine Arts. Source: Web Gallery of Art

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown (Flemish). Marguerite de Bavière, ca. 1363-1424. Oil on wood. Lille: musée de l'Hospice Comtesse. Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais / Jacques Quecq d'Henripret. Source: L'Agence Photo RMN

About the Accessories

Fig. 11 - Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, ca. 1390-1441). Margaret, the Artist's Wife, 1439. Oil on canvas; 41.2cm x 34.6 cm (16.2 x 13.6 in). London: The National Gallery. Source: The National Gallery

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown (French). Book of Hours, "The Dunois Hours", ca. 1440 - 1450. London: The British Library. Source: Pinterest

Isabella wears various accessories in the portrait, including golden rings, a pearl necklace and a head-piece adorned with jewels: all of which convey of her aristocratic status. The head-piece is being used in a crown-like manner. This head-piece is a heart-shaped bourrelet, which was often adorned with a linen or silk veil hanging from the point or held on brass wires to form a butterfly shape head-dress (Brown 74).

This style was mainly worn in Northern France, Burgundy and the Low Countries. It was never a current trend in England, Italy or Spain (Boucher 200). Several aristocratic female figures of Northern France, Burgundy, and the Low Countries were depicted wearing the heart-shaped bourrelet, like Marguerite de Bavière, who was duchess consort of Burgundy and mother-in-law of Isabella of Portugal (Fig. 10), Marguerite d’Orleans, Countess of Vertus (Northwest France) (Fig. 7), and Mary of Guelders, born in the Netherlands (Fig. 6).

This head-style developed from the “horned head-dress” worn at the beginning of the century (Fig. 2, 9, 11). Isabella of Portugal wore bourrelets in different shapes and forms (Figs. 1, 3, 4). Although Isabella’s feet are not depicted in the portrait, it can be assumed she was wearing poulaines, and pattens still protected their tight shoes (Boucher 201). The costume was made by hand, since there were no sewing machines in the 15th century.

Another contemporaneous artwork of this time (Fig. 12), a French Book of Hours, shows the same style of dress and head-dress worn by Isabella of Portugal. Moreover, a surviving purse in red velvet brocade from the 15th century (Fig. 13) may have belonged to a member of the nobility of the time.

Fig. 13 - Maker unknown (Northern European). Purse, late 15th century. Iron, red velvet brocade; 31.2 x 22.8 x 2.5 cm (15 x 13.2 x 2.5 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 52.121.3. The Cloisters Collection, 1952. Source: The Met

Its Legacy

Over the years artists and designers have been continually inspired by the 15th-century fashion. Contemporary designers keep re-interpreting the V-neck gown in a myriad ways. In the Fall/Winter 2016 collection, two designers alone took inspiration from this era. Elie Saab (Fig. 14) kept iconic 15th Century elements like the belt, the long sleeves, the floor-length skirt, the plunging V-neck and the necklace. Valentino (Fig. 15) also played with the V-neck line, the necklace, the full sleeves and red color.

Fig. 14 - Elie Saab (Lebanese, 1964-). F/W 2016 Couture. Source: Vogue

Fig. 15 - Pier Paolo Piccioli and Maria Grazia Chiuri for Valentino (Italian). F/W 2016 Couture. Source: Vogue

References:

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment. Expanded ed. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/990429904.

- Brown, Susan, ed. Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. New York: DK Publishing, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/840417029.

- Campbell, Lorne and Périer-d’Ieteren, C. “Weyden, van der.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed December 1, 2017, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T091309pg1.

- Campbell, Lorne, and Christopher Wright. Van der Weyden. London: Chaucer Press, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/957194740

- Clark, Kenneth. Looking at Pictures. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1960. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/988731143.

- Davenport, Millia. The Book of Costume. New York: Crown Publishers, 1948. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/786259658.

- Houston, Mary G. Medieval Costume in England and France: The 13th, 14th, and 15th Centuries. New York: Dover Publications, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/491756801.

- “Isabella of Portugal, Duchess of Burgundy – History of Royal Women.” Accessed December 2, 2017. https://www.historyofroyalwomen.com/isabella-of-portugal/isabella-portugal-duchess-burgundy/#return-note-24130-1.

- National Gallery (Great Britain), and Lorne Campbell. The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Schools. London; [New Haven: National Gallery Publications, 1998. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1001169424.

- Panofsky, Erwin. Early Netherlandish Painting. The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures 1947–1948. New York: Harper & Row, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/315679404.

- Payne, Blanche. History of Costume: From the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century. New York: Harper & Row, 1965. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/777277049.

- “Portrait of Isabella of Portugal (Getty Museum).” The J. Paul Getty in Los Angeles. Accessed December 4, 2017. http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/651/workshop-of-rogier-van-der-weyden-portrait-of-isabella-of-portugal-netherlandish-about-1450/.

- Taylor, Aline S, and Robert Oresko. Isabel of Burgundy: The Duchess Who Played Politics in the Age of Joan of Arc, 1397-1471. Stroud: Tempus, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/806246794.

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume: A History of Western Dress. 3rd ed. New York: Fairchild Publications, 1998. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/926775418.