Often anachronistically called the ‘S-bend,’ the dramatic straight-front corset of the early 1900s was invented by a doctor for health purposes and quickly swept up into the tides of fashion.

The shape of corsets is undergoing a radical change,” an unnamed Vogue author wrote in “Piazza Talk” for readers in July 1896.

“From the long waist and high bust recently considered correct they are now made with shorter waists, straight fronts and lower bust. This change is just sufficient to give one who is always bien mise something to do. Indeed, fashion makers evidently fear we may disappear with dry rot, so assiduous are they in mapping out for us labors sufficient to prevent such a catastrophe.” (vii)

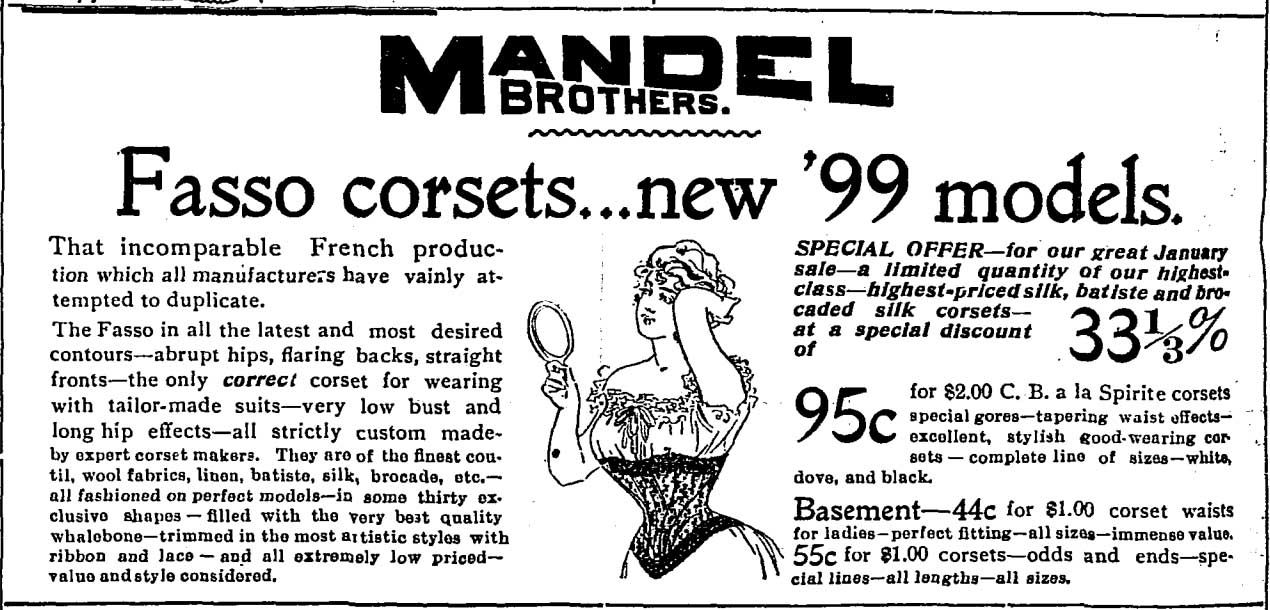

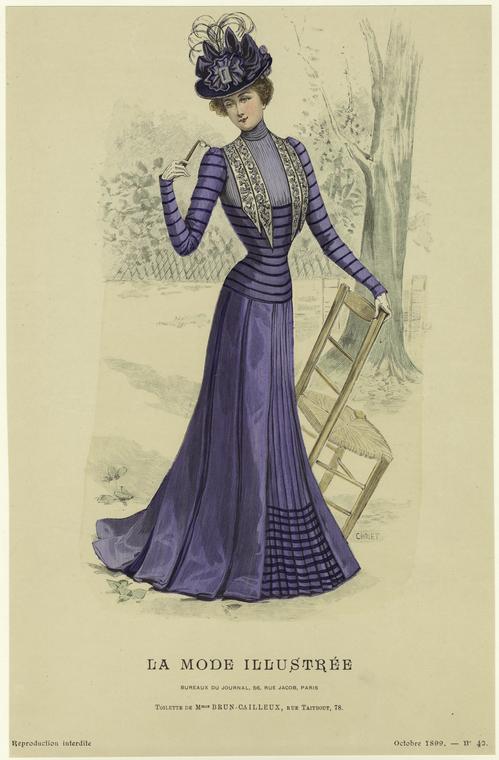

This silhouette (Fig. 1)–“straight front, low bust, and sudden hips,” as one advertiser put it–crept into fashion slowly rather than emerging explosively (“Fasso”). By 1900 it was the prevailing look and directed female dressing and comportment for more than a decade (Fig. 2).

In retrospect, it almost seems to have appeared out of nowhere. Corsets had barely changed between the 1840s and the 1890s; how did such a drastic shape suddenly come into being, and why was it so fashionable?

The answer: hygiene. But not the kind you might think…

Health corsets

A running theme in discussion of women’s dress and foundation garments in every era is the potential health drawbacks. Think of all the arguments against high heels today; the same held true for corsets. But unlike heels, corsets were necessary for most women because they were a structural garment meant to support the bust. Early brassieres existed, but they did not catch on until the nineteen teens (Tortora 434).

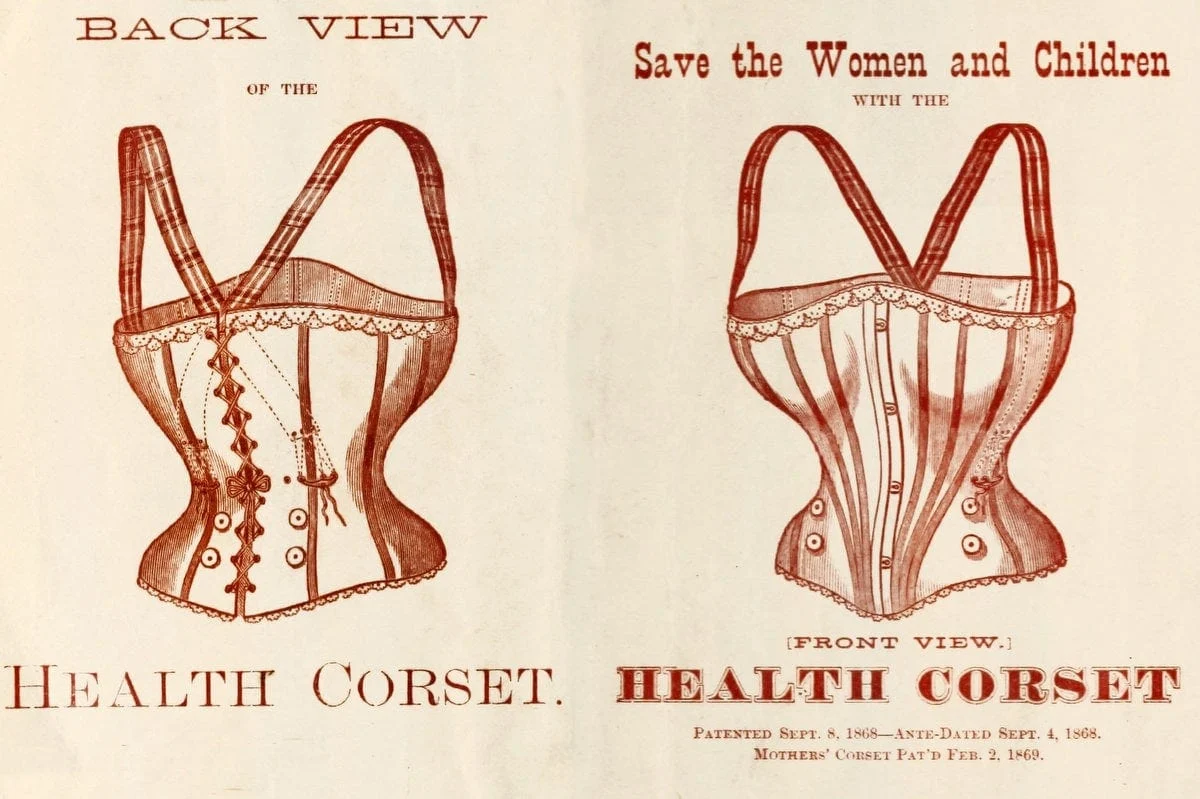

In order to create a more comfortable and supportive corset, doctors frequently took turns as corset designers (Steele 41). They published patents for “health” and “hygienic” corsets throughout the century–many of which did go into production (Fig. 3). As one author put it in 1900:

“Once in six months, on an average, a new “hygienic” corset is put on the market, but not more than once in a lifetime does it deserve its name.” (“Avoiding its Evils”)

Hygiene–by which they meant the overall health of the body and not just cleanliness–was something that all could agree was important. The controversies around corsetry and tight-lacing also meant that there was great public interest around these new designs (Fig. 4) (Steele 4, 76). Even if there was no true scientific proof that a design was more comfortable than its predecessors, there would be buyers. In short: ‘health corsets’ sold.

Many of them involved lightweight fabrics, new materials, and elastics; buttons instead of metal busks; and new cuts and shaping. Corsets do not gain their dramatic shapes because they are boned, after all; it is the way the fabric is cut that shapes the body underneath. And in the late nineteenth century, corsetières realized that there was a major change they could make to that shaping–a change that might redefine the entire female experience.

Fig. 1 - Simpson, Crawford, & Simpson (American). Corsets, May 5, 1898. Vogue. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 2 - Elmer Chickering (American, 1857-1915). Bianca Lyons, ca. 1902. B&w film copy negative. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, cph 3b11241. Source: LOC

Fig. 3 - Dr. Warner's. Coraline Health Corset, 1889-91. Cotton, metal, bone. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.3015a–c. Source: MMA

Fig. 4 - Thos. W. Love & Co. (American). Save the women and children with the health corset, 1869. Pamphlet. New York: Columbia University Libraries. Source: Archive.org

Inès Gâches-Sarraute and the ‘abdominal corset’

Dr. Gâches-Sarraute (1853-1928) held dual interests in corsetry and medicine. Many of the women she treated had come to her because of gynecological issues, and from 1890 onwards she worked to develop a supportive corset that might solve many of their problems (Gâches-Sarraute 74). As historian Susan Pryor wrote for a Colonial Williamsburg research report (1990):

“Mme. Gaches-Sarraute realized the importance of leaving the thorax free and yet still supporting the abdomen. In fact, she introduced the straight-fronted busk whose design supported and raised the abdomen instead of compressing it and forcing it down. She attempted to eliminate the constricting inward curve at the waist, thus removing pressure on the diaphragm and abdomen, including vital female organs.” (11-12)

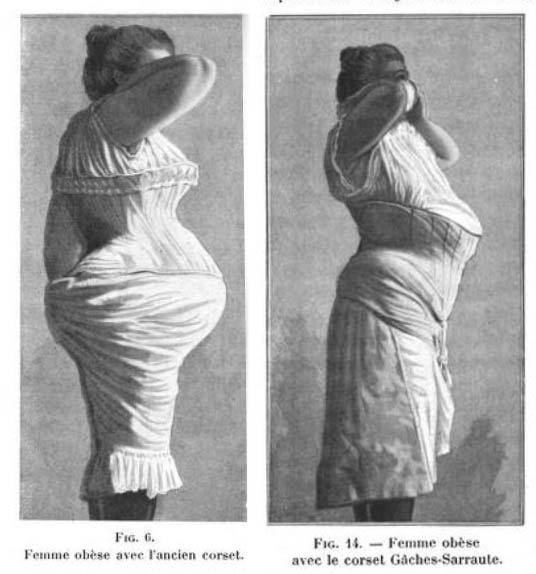

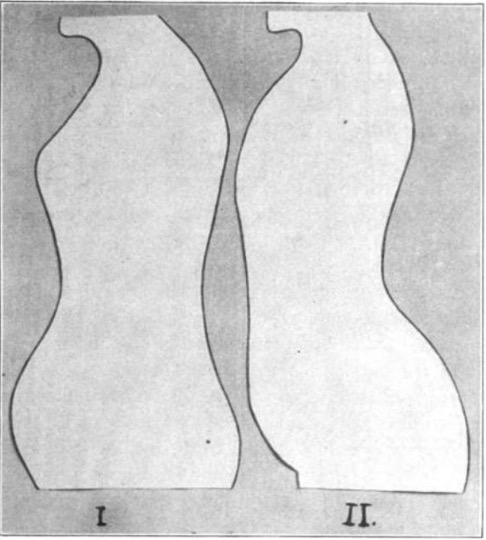

She provided visual comparisons of her version–the ‘abdominal corset’–against the older style for readers, showing how they affected the body and gave support for her patients’ need (Fig. 5). It is important to recognize that these corsets were not meant to be fashionable: they were medical devices meant to help her patients heal. However, she believed her successes with them would make for a healthier living experience across the board. Her promotion of the style as a healthy form of corsetry did exactly what previous forms of health and hygienic corsets had done: it sold. However, unlike its predecessors, it was unique enough in shape that it inspired waves of imitators, from Fasso to Erect Form to Kabo, who saw a chance to develop fashions and outsell a dwindling older style.

Dr. Gâches-Sarraute published a book on her findings, Le corset: étude physiologique et pratique, in 1900 (Fig. 6). However, we know that at least as early as June 1896 she had provided pamphlets to journalists, and that in January 1896 she had given a conference on the topic for the Union des Femmes de France in Paris (Ludka 29; “Bicyclette et Corset” 3). It is likely that she had been doing so for a while and that others snapped up the design and competed with her. However, it is also possible that she was working collaboratively or that similar designs were developed independently by other French doctors (Steele 84). Dr. Gâches-Sarraute is traditionally credited with the design and its introduction into fashion; whether or not she is the sole originator, she had an extremely important part to play in the design’s spread.

Fig. 5 - Inès Gâches-Sarraute (French, 1853-1928). The old style corset versus the Gâches-Sarraute corset, 1890s. Book. Le corset: étude physiologique et pratique. Source: Archive.org

Fig. 6 - Inés Gâches-Sarraute (French, 1853-1928). Femme normale avec le corset Gâches Sarraute, 1890s. Source: Archive.org

Fig. 7 - Edwin Izod (British, 1826-1887). Wedding corset, 1887. Satin, coutil, silk thread, silk braid, lace. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.265&A-1960. Source: VAM

Fig. 8 - Warner (American, 1970s-1950s). 'Rust Proof' Style 602 Flossed Corset, late 1890s. Cotton sateen, coraline & steel boning, lace. Underpinnings Museum, KL-2020-014. Source: Underpinnings Museum

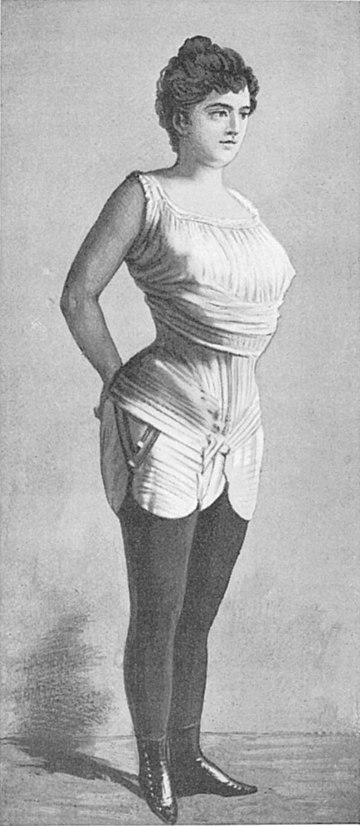

Corset Evolution

As women’s clothing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was usually fitted around the torso, the shape of the clothing echoed the shape of the corset. Not every corset was comfortable on every body, and the best were custom-fitted. However, most people used premade corsets – what we would now call readymade or off-the-rack. Body fat, if there is enough of it, can shift to fill the available space. This is how one woman might go through the progression of corsets from figure 7 to figure 11 within the space of only two decades: her body is not changing but merely squishing to shape.

The rounded hips, bust, and belly seen in the 1887 corset (Fig. 7) became a high bust and flatter belly by the late 1890s (Fig. 8). In the early 1900s, that shape relaxed, lowering the bust (Fig. 9) and giving enormous room to the hips and bum by 1905 (Fig. 10).

Corsets became longer to smooth the way for close-fitting skirts, and as brassieres became common they forwent bust support entirely. By 1915-1920, they straightened out and slimmed down the hips (Fig. 11), resulting in a silhouette that forecasted the ‘flapper’ look of the 1920s.

Figures 8-11 are all ‘straight front’ styles, though only the last two are really what we would think of as iconic shapes of the era because of their low bustlines and lengthened hips. This is part of the difficulty of naming such a style: not every corset in this era possessed each of the iconic attributes (‘low bust, straight front, sudden hip’).

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (German). Corset, ca. 1903. Cotton broché, machine lace, silk ribbon, metal. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.97&A-1984. Source: VAM

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown. Corset, 1900-1905. Figured silk, metal bones. Montreal: Musée McCord Stewart, M968.7.59. Gift of Mrs. A. Murray Vaughan. Source: MMCS

Fig. 11 - Parisian Corset Co. Ltd. (French). Corset, about 1915. Cotton coutil, steel boning. Montreal: Musée McCord Stewart, M2004.101.16.1-2. Gift of the Estate of Luc J. Béland. Source: MMCS

The Straight Front in Fashion

In December 1897, an anonymous author wrote in Godey’s Magazine of the newly emerging straight-front (French: droit devant) corset:

“The flat-fronted bias-cut corset is the latest novelty in stays, and needless to say it emanates from Paris. It is shaped with a number of gores forming curved bias sides; this corset conforms to the figure, following closely the curve of the waist and allowing the hips to swell out suddenly, hence its name, the sudden hip-corset. It also leaves the bust uncompressed, avoiding the pushed-up effect so unnatural and ugly where a woman possesses a surplus of flesh.” (663)

As the new style spread, audiences wondered what to call it. ‘The new corset’ is only so catchy, after all. The name ‘sudden-hip’ was tossed around by several advertisers and columnists in 1897, but department stores like B. Altman did not depend solely on the provocative name, adding in terms like “straight front” and “low bust” to fully describe the style (“Fasso Corset”) (Fig. 12).

However, the actual timeframe of introduction for the new style is murky. An author for Cloaks and Furs (July 1897) claims that this style of corset, as exemplified by the Fasso in which “all the curves come from the sides and the bust gore runs straight to the waist line,” was “introduced to the American public about four years ago but not until two years ago did it even assume the proportions of a fad with the exclusive set” (“Corsets and Cloaks” 16). If the new style was really introduced around 1893 it is impossible to tell, but ad copy and fashion columns in American magazines do not begin to depict or discuss anything resembling such a style until 1896, when the Pansy Corset Company began advertising its “New Straight Front Corsets” (“A Perfect Corset”). Importantly, while the extended bust gores are visible on their design, the overall silhouette remains in mid-1890s fashion, as if the manufacturers thought that buyers were not yet ready to embrace the change wholeheartedly.

The change in silhouette–from straight-backed to straight-fronted with a marked arch to the back–occurred slowly in fashion plates in the late 1890s. Backs begin arching noticeably by 1896 (Fig. 13) and by 1897 we begin to see skirt fronts flattening (Fig. 14). By 1899 the fashionable silhouette is established (Fig. 15): a smooth look with pronounced bust and bum and no belly to be seen. The sinuous lines of the fashion fit perfectly into the Art Nouveau style and brought women’s clothing into the twenty-first century.

American fashionistas were able to imitate these French styles within months, if not weeks, but the new corset and silhouette did not enter common dress for several years. Even then, there was the issue of posture and the ideal body…

Fig. 12 - Fasso (French). Fasso corsets...new '99 models, January 5, 1899. Chicago Daily Tribune, p. 12. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 13 - Designer unknown (French). Summer dress, 1896. Fashion plate. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17520939. Source: WatsonOnline

Fig. 14 - Designer unknown (French). Le bon ton et le moniteur de la mode united, November 1897. Fashion plate. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17520939. Source: WatsonOnline

Fig. 15 - Deun-Cailleux (French). Woman in dress, outdoors, Paris, France, 1899, October 1899. Fashion plate. New York Public Library, 816177. Source: NYPL

Fig. 16 - Lydia Ross (American). I. Normal stance; II. Affected posture, 1904-5. Shadowgraphs. Source: Google Books

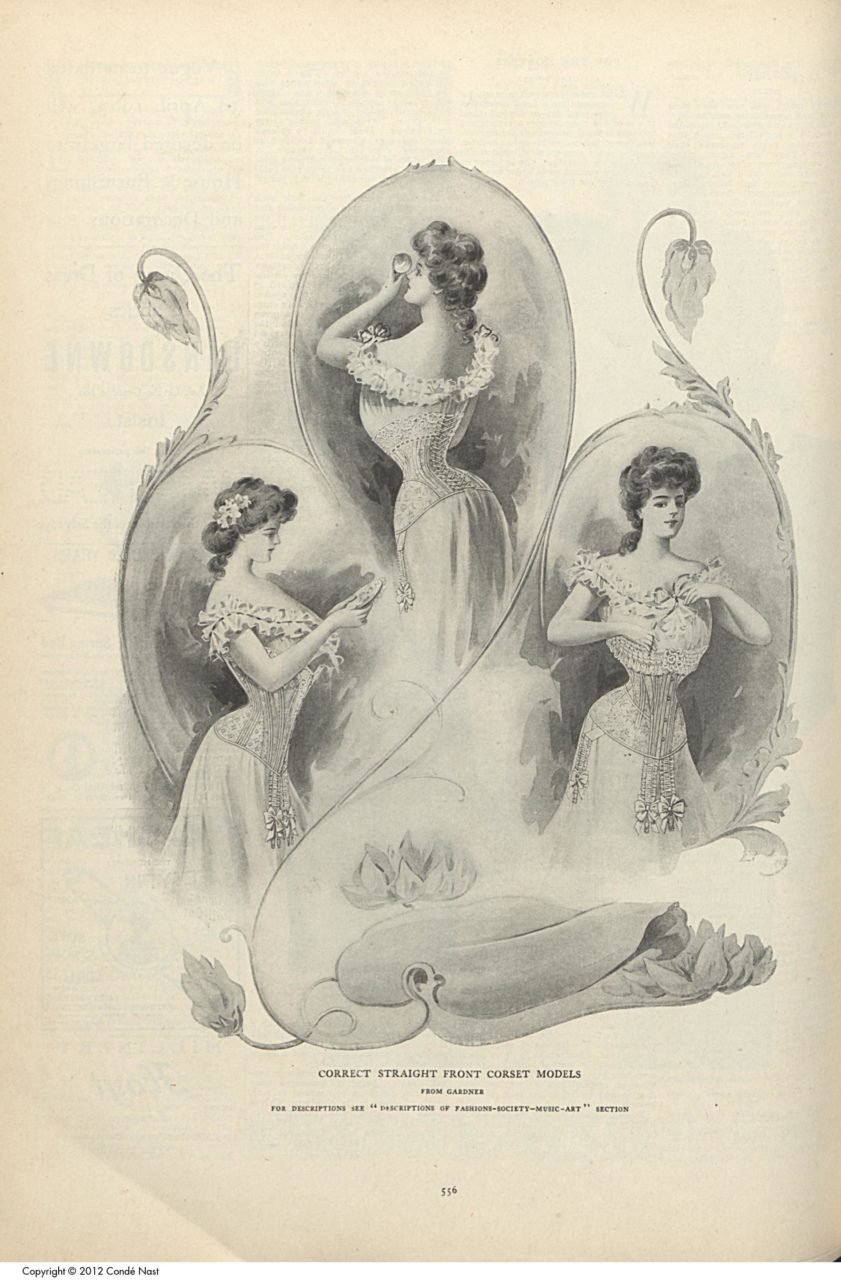

Fig. 17 - Mme. Gardner (American, active 1900-14). Correct Straight Front Corset Models, April 16, 1903. Vogue. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 18 - Ede Rauch (Hungarian). Portrait of a woman, 1905. Photograph. Collection of György Ungvári. Source: Fortepan

Posing with Intent

While the cut of the new corsets made room for a low bust and encouraged an apparent arch in the back by leaving room at the back of the hips and bum for fat, the corset alone did not make this new silhouette. It had to be paired with the correct garments – also cut to enhance the bosom and rear and smooth out the belly – and, most importantly, standing a certain way. Take a look at figure 16, which shows two outlined profiles of a female torso:

“No I. shows the outlines of the corseted figure in her usual standing position. Without removing the corset she was shown how to poise the body more normally with the result outlined in No. II.” (“The Poise Centre” 94-5)

These are the words of Lydia Ross, a doctor who sought to provide women with the means to achieve the ‘correct’ posture (Fig. 17) with the new corsets, which could only do so much on their own. Their boning–whether steel, whalebone, or a synthetic–was not designed to hold the female form rigid. It was highly flexible and designed instead to support the corset itself to ensure it remained smooth and did not wrinkle. Bending at the waist was easily done, and a casual slouch just the same–so of course the corset could deform with the pressure from an ‘incorrect’ (natural) posture.

The fanciful and severe shapes of women in fashion plates and advertisments were a fiction, as any fashion plate was in the nineteenth century. And the doctoring of photographs “was already well established” by this time; experts removed bulk from waists and bellies on popular cabinet card portraits and added bust and bum (Taylor 162). So what did the straight-front silhouette look like on ordinary women?

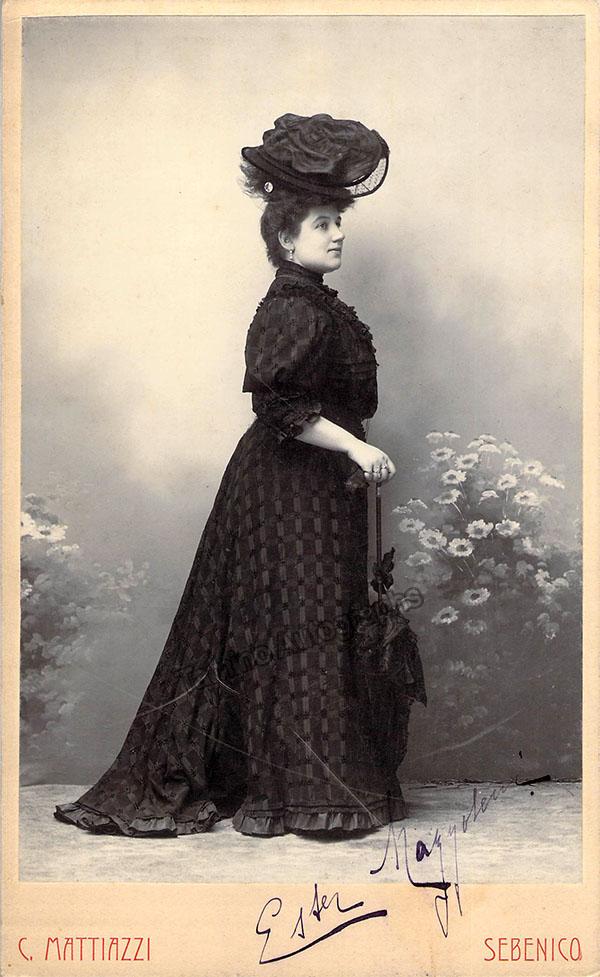

We can see from photographs that people could achieve the correct look with bloused bodices and padding in the right places, but that affecting the correct stance was key (Fig. 18). Bianca Bellincioni (Fig. 19) hits it perfectly, while the anonymous woman in figure 20 and opera singer Ester Mazzoleni in figure 21 both have more natural posture. While the latter two are dressed well and are certainly wearing the correct underthings, they fail to achieve Bianca’s fashion-plate-perfect look.

The new silhouette was an investment: buying the new ‘French corset’ and wearing it under your clothing from previous years was not going to cut it. Women had to learn to stand in a certain way and rely on a particular cut of corset, bodice, and skirt if they wished to be considered fashionable in this era.

Fig. 19 - Mario Nunes Vais (Italian, 1856–1932). Bianca Stagno Bellincioni, ca. 1901. Photograph. Florence: Collezione del Fondo Nunes Vais. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 20 - Edward Linley Sambourne (British, 1844-1910). Street style in Kensington, 1906. Photograph. Source: Rare Historical Photos

Fig. 21 - C. Mattiazzi (Croatian). Ester Mazzoleni (1883-1982), ca. 1905. Photograph; (5.25 x 8.5 in). Private collection. Source: Tamino Autographs

Legacy: Misnomers and Erasure

The corset and silhouette predominant in fashion during the years 1900-1915 are now nearly without fail called the ‘S-bend’ or ‘S-curve’ in the popular press and academic publications alike. Where does this odd term come from, and why isn’t it a “V-bend” or “R-swoop” instead?

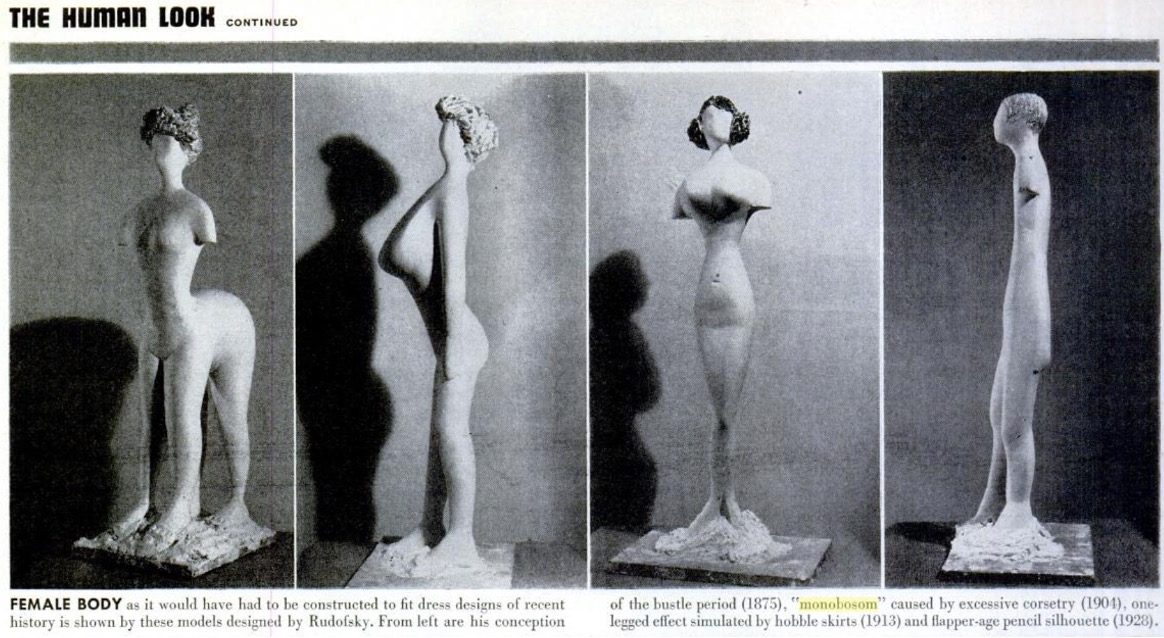

The straight-front style has attracted attention as a curious and unique historical fashion since the 1930s. “S-bend” is not the only post-period misnomer given to the style: perhaps you’ve heard ‘monobosom’ or ‘pigeon breast’, and 1940 Vogue called it ‘swaybacked’ (lordotic–surprisingly accurate). These early twentieth-century fashions can be awkward to name from a distance, which is why looking at contemporary sources is so important.

In addition to “straight front” (Fig. 22) it was variously called names like “the French corset,” “the new style,” “Louis XV corset,” “Marie Antoinette corset,” and so on. Like ‘sudden hip,’ these did not stick; they were too general and could easily refer to non-straight-fronted styles. Dr. Gâches-Sarraute’s term ‘abdominal corset’ suffers from the same ambiguity, as many health corsets had previously used the phrase. ‘Straight-front,’ of course, has the helpful benefit of being able to refer to both the corset and the overall silhouette where modern terms fail to do both.

‘Monobosom’

In 1946, architect Bernard Rudofsky curated an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Are Clothes Modern? he asked. In it, he displayed a series of caricature figurines (Fig. 23), one of which was based on the fashions of this era. He called this the ‘monobosom’ silhouette, as he felt that a protruding bust was the style’s iconic signifier. However, Rudofsky was a critic, not a supporter: he saw fashions like these as a “struggle against reality” and his caricaturing came from a place of patriarchal disdain (“The Human Look: A designer finds fashions ruin it”). He did not acknowledge the art that went into artifice when he coined ‘monobosom’ – and, worse, ‘mono-buttock’ to refer to the bustle era of the 1880s. And Rudofsky’s judgment aside, the bosom of this era (Fig. 24) was, really, no more singular than the bosom of the preceding eras.

‘S-Bend’ & La Sylphe

Even more enduring in fashion writing than ‘monobosom’ is the descriptor ‘S-bend’. Tracing the term’s development is a project in and of itself that involves searching foundational mid-century books on dress history. It begins to appear in the late 1930s, decades after the garment’s heyday.

Fig. 22 - Fasso (French). Fasso Corset, Oct 7, 1897. Vogue. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 23 - Bernard Rudofsky (Austrian-American, 1905-1988). The Human Look: A designer finds fashions ruin it, LIFE, September 23, 1946, 99-100. Source: Google Books

Fig. 24 - Photographer unknown (American). Jessie Gideon Garnett, ca. 1908. Photograph. Boston. Source: Wikimedia Commons

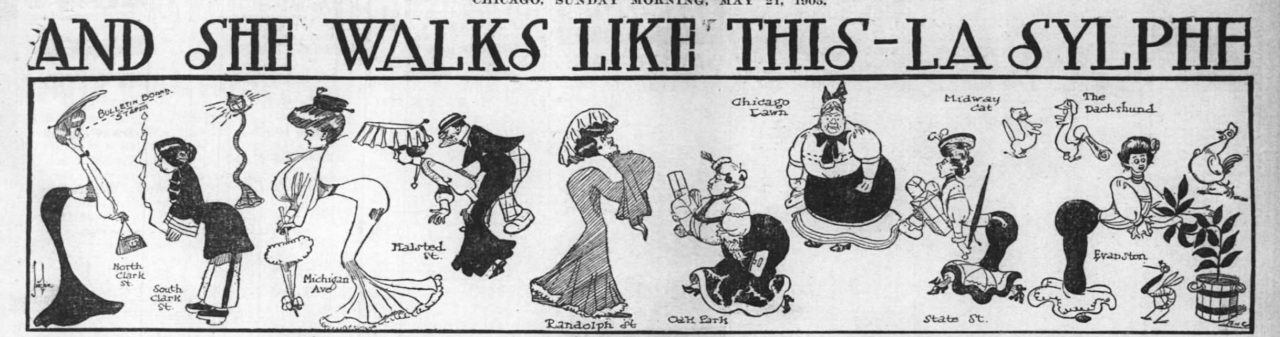

Fig. 25 - Artist unknown (signed TONC) (American). The Inter Ocean, Sunday, May 21, 1905. Newspaper. Chicago, Ill. Source: Newspapers.com

James Laver wrote in 1937 of “the S-shaped corset,” though in later publications he avoided the term, using instead “health corset,” “l’art nouveau,” and the more general “S-shaped stance” (Laver 1937; 1979, 213). Historian Doris Langley Moore spoke in 1949 of the “straight-fronted corset [giving] the back the desired ‘S’ curve…sometimes called the S-corset” (32, 148). From the 1970s onward the term is used in most volumes on Edwardian and Belle Epoque fashion–probably in part thanks to ex-Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, who highlighted the “serpentine S-shape” along with “monobosom” in the 1973 Met Costume Institute exhibit “The 10’s, the 20’s, the 30’s: Inventive Clothes 1909-1939.”

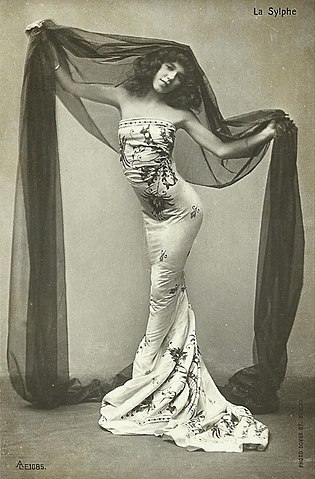

This anachronistic term most likely grew out of a particular and short-lived fad that began in 1905 inspired by the dancer La Sylphe (Edith Lambelle Langerfeld, 1883-1968). This was a particular way of posing and walking called the “Sylphist” or “La Sylphe” bend, and those who attempted it were known as “Sylphists” (Fig. 25) (“And She Walks Like This”). “‘La Sylphe’ bend as a society fad had its origin in London,” the author writes, “However, it owes its origin to India, where it is the natural pose of the Nautch dancing girls” (Fig. 26). The affectation is not one that persisted, and in fact the use of the name “Sylph” for corsets caught on only in the 1910s as a slimmer figure began to win out over the heavily curved form of the early 1900s. (Langerfeld herself was slim, a trait which earned her the name La Sylphe, and in press photographs like figure 27 she does not wear corsets or the fashionable clothing of the time at all.)

The “La Sylphe bend”, we learn, was not attributed at large to the corset or silhouette of this era; it was a particular–and Orientalist–way of posing popular for a brief time.

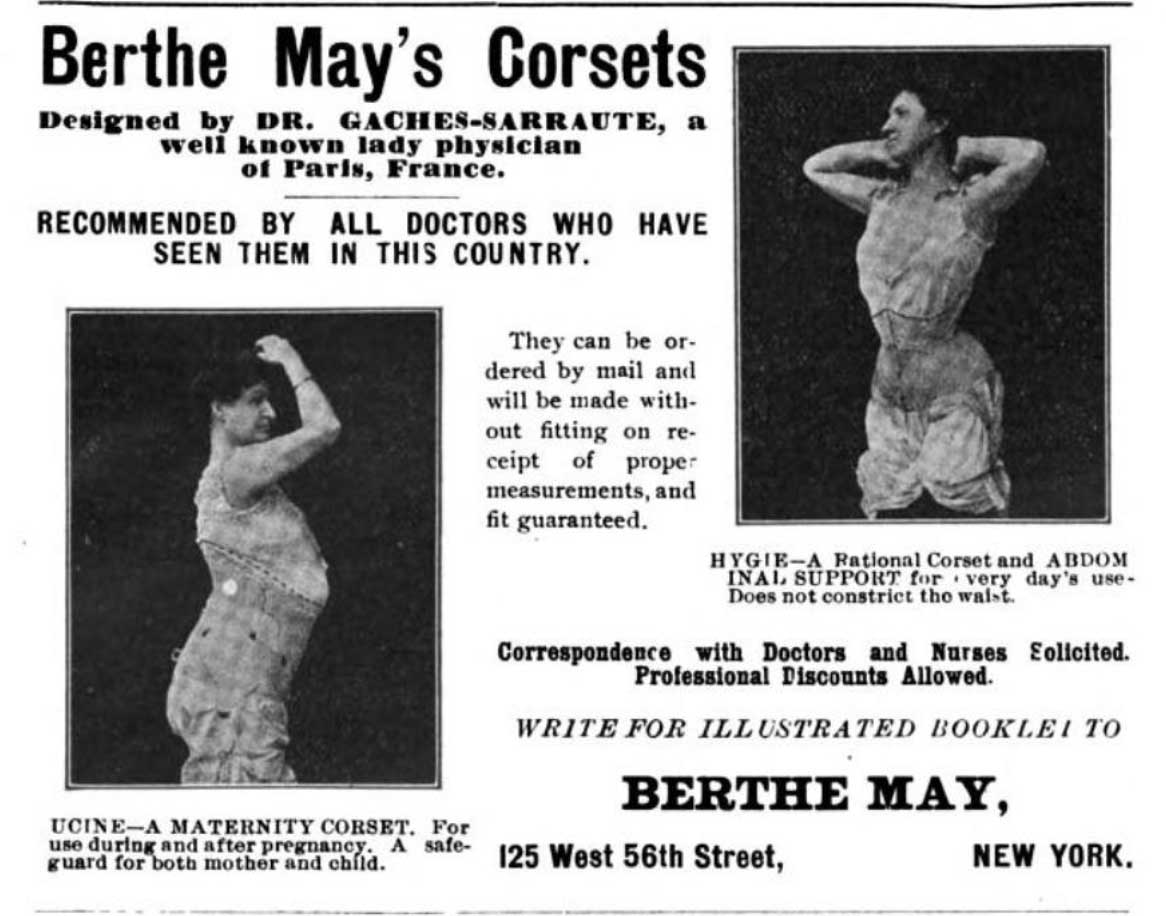

Honoring the Originator

While Dr. Inès Gâches-Sarraute (Fig. 28) and her efforts were sometimes honored as part of the corset’s name and advertising early in the century (Fig. 29), later historians have erased her part in favor of the simpler route of naming the thing by its appearance (Poiret 63). The doctor cared deeply about acknowledgement and attempted to confront her competition, going so far as to bring a civil suit against Maison Henri Vion in 1901 for infringing upon her image as the female docteur-couturière of the new style (“Tribunal” 438). She claimed he had pulled the design for his patent from her published book; unfortunately, she could only sue for brand confusion, and the judge sided with Vion.

Admittedly, the only true Gâches-Sarraute corsets are those designed by her, and almost all commercially-sold corsets in the era were not made under her purview. “Straight front,” therefore, remains the most accurate term for these corsets as it was the most heavily used name for the style in period.

While the Gâches-Sarraute straight-front corset was not, in the end, healthier for women than the older styles, it electrified the Parisian dress scene and led followers of European fashion into a new era full of arched backs and swooping skirts (Fig. 30) (Steele 84).

Fig. 26 - Charles Shepherd (British (active Simla, India), fl. 1858–1878). Nautch girls India, 1870. Albumen paper process; 22 × 28.5 cm. Private collection. Source: Catawiki

Fig. 27 - Dover Street Studios Ltd. (British, active c.1906-c.1912). La Sylphe, ca. 1908. Photograph. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 28 - Photographer unknown (French). Madame le Dr Gaches-Barthélémy (de Paris), late 1890s. Photogravure. Bibliothèque de l'Académie nationale de médecine. Source: Bibliothèques d'Université Paris Cité

Fig. 29 - Berthe May (American). Berthe May's Corsets designed by Dr. Gaches-Sarraute, October 1908. Source: Google Books

Fig. 30 - Alfred Choubrac (French, 1853-1902). Corsets Baleinine Incassables, ca. 1905. Color lithograph poster backed with linen; 93.5 x 128.7 cm (36 3/4 x 50 3/4 in). Private collection. Source: Invaluable

References:

- “A Perfect Corset.” Vogue (New York) 7, no. 24, (June 11, 1896): 413. ProQuest.

- “Avoiding its Evils.” The New York Tribune (February 11, 1900). ProQuest.

- “Bicyclette et Corset.” La Presse (January 14, 1896). Gallica.

- “Corsets and Cloaks.” Cloaks and Furs (New York) 26, no. 12 (July 1897). Google Books.

- “Early Autumn Fabrics, Trimmings and Accessories.” The Delineator (September 1905): 336. Google Books.

- “Fashion: Piazza Talk.” Vogue (New York) 8, no. 3 (July 16, 1896): vii. ProQuest.

- “Fasso Corset.” Harper’s Bazaar 30, no. 22, (May 29, 1897): 454-455. ProQuest.

- Gâches-Sarraute, Inès. Le Corset: étude physiologique et pratique. Paris: Masson et Cie, 1900. Google Books.

- Godey’s. “Woman and Home: The Sudden Hip-Corset.” Godey’s Magazine 135, no. 810 (December 1897): 663. Google Books.

- Laver, James, and Christina Probert. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. Oxford University Press, 1979. Worldcat.

- Laver, James. Taste and Fashion from the French Revolution until Today. London: G.G. Harrap & Co, 1937. Worldcat.

- Ludka. “La Mode Dans Le Monde.” Le Monde Illustré (July 11, 1896). Gallica.

- Moore, Doris Langley. The Woman in Fashion. London: B.T. Batsford, 1949. Worldcat.

- Poiret, Paul. En Habillant l’Époque. Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1930. Gallica.

- Pryor, Susan. “On Taking Great Pains With Fashion.” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series 324 (1990). https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/view/index.cfm?doc=ResearchReports%5CRR0324.xml

- Ross, Lydia. “The Poise Centre.” Transactions of the National Eclectic Medical Association, 1905, 94-5. Google Books.

- Steele, Valerie. The Corset: A Cultural History. New Haven: Yale UP, 2001. Archive.org.

- Taylor, Lou. The Study of Dress History. Manchester UP, 2002. Worldcat.

- “Tribunal civil de la seine, 16 décembre 1901,” La Gazette du palais: jurisprudence et legislation, 1er semestre 1902, 438. Google Books.

- Vreeland, Diana. The 10’s, the 20’s, the 30’s: Inventive Clothes 1909-1939. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973. Read here.