This green André Courrèges coat is a quintessential example of 1960s mod style, maintaining a delicate balance between the Space Age vibes of its synthetic material and the freedom of its functionality.

About the Look

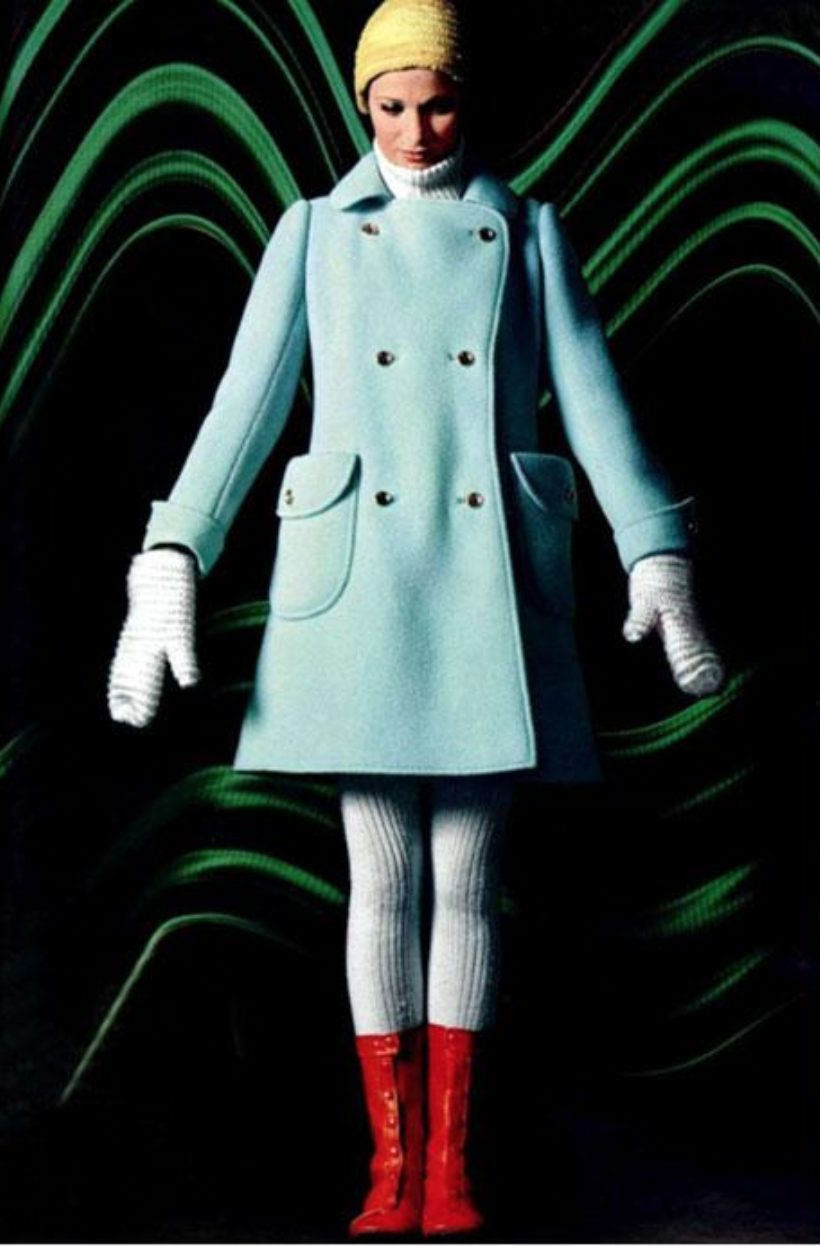

The use of vinyl fabric for the coat creates a sportier look than the wool or acrylic blends that were popular for outerwear at this time. In addition, the front pockets are easily accessible, following his practice of functionality. This design can be worn either as a coat or a dress. The belt clearly defines the waist, and the buttons and high collar give the wearer options for warmth or modesty. Figures 2 & 3 are additional colorways of the same garment, showing the variety of strong color in his designs.

Fig. 1 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). Coat, 1963-69. Source: Pinterest (Etsy)

Fig. 2 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). Coat, 1972. Cotton and synthetic. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006.146a–c. Gift of Florence Irving, 2006. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 3 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). Courreges orange vinyl coat dress, c. 1970, 1970. Vinyl. LU14021163622. Source: 1stdibs

André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). Coat, 1963-69. Cotton, polyurethane, acrylic. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984.601.5a, b. Gift of Mrs. Howard L. Ross, 1984. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

About the context

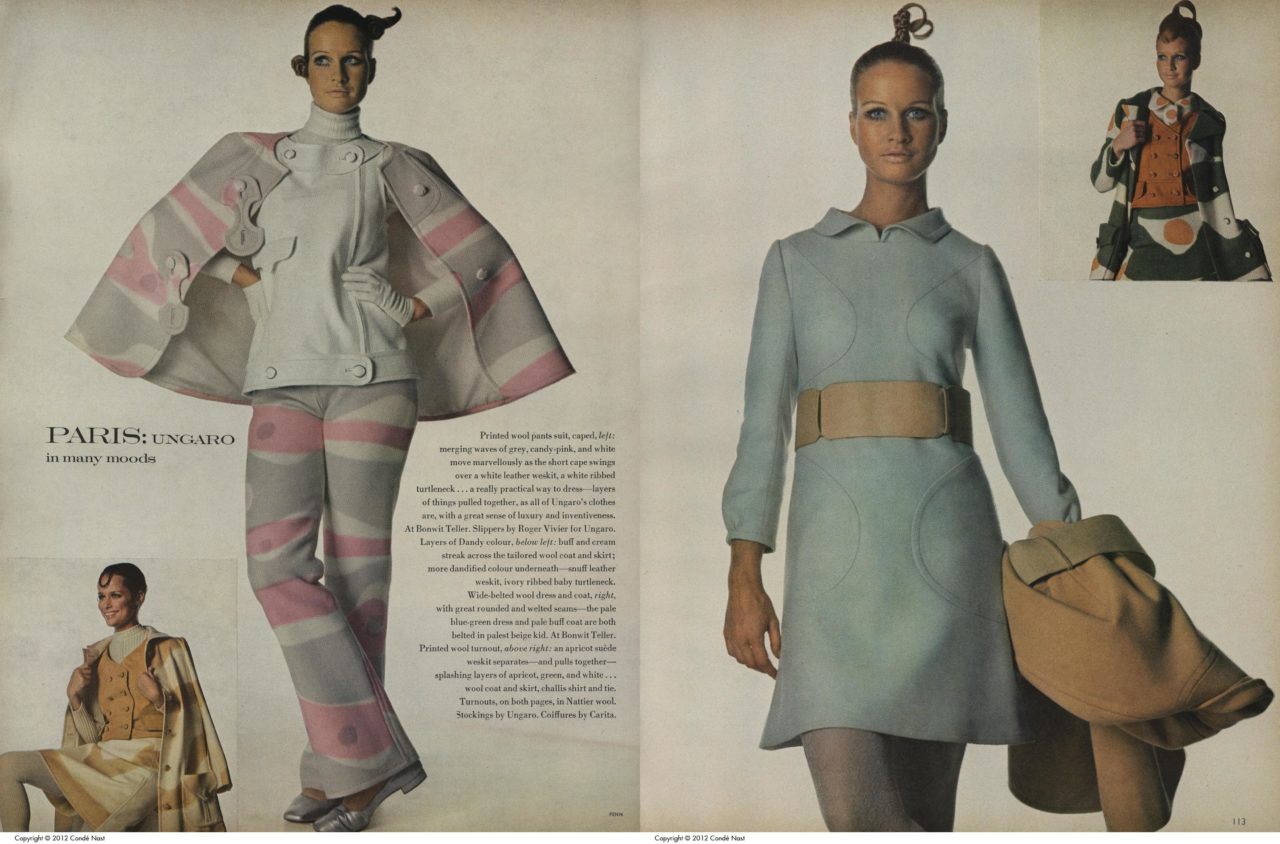

As the “father of Space Age fashion,” André Courrèges is one of the most influential designers of the 20th century (WWD). His functional approach to womenswear was made attractive by its modern twists. He provided the fashion industry with controversial imagery based on contemporary societal events. Political struggles earned women more freedom and consequently they began dressing differently (Dwyer 3). The energy of society in this time is reflected in Courrèges’ designs, as well as in the work of other prominent designers from the decade like Emanuel Ungaro (Fig. 4).

With the help of his wife Coqueline, Courrèges found a unique style. The duo paved the way for more comfortable silhouettes that gave women freedom of movement. In Courrèges (1998), Valérie Guillaume writes that “Coqueline recalls how women who until then had been restricted by tight skirts and high heels, were suddenly skipping along” (7). In addition to prioritizing wearability, Courrèges loved the look of sportswear and integrated its concepts as one of his signature styles.

Guillaume discusses how “Courrèges made the fashion world recognize and reflect the role of sport in modern life… for him sport represented a way of life, a code of behavior” (10). Figure 5 displays a sporty 1970 raincoat with a matching hat published in L’Officiel. Courrèges believed that women’s clothes should be unconventional, and the fluidity and modernism of the 60s provided the perfect platform for his ideas. As Guillaume describes,“Courrèges sees his creations as a vehicle for ideas that are not constrained by fashion. His inspiration comes from the modern world of industry and not the world of fashion, which is too driven by styles and trends” (14). The perfect fit, according to Courrèges,

“was somewhere between a youthful and optimistic inventiveness, and a concept of fashion embracing the platonic ideal of perfect form. What was needed was to apply new technical and aesthetic rules and to create a modern style that was easy to wear” (4).

When the synthetic textiles revolution began in the 1960s, Courrèges started experimenting with specialized materials that had previously only used by the military and the aviation industry. These unusual materials were crucial to his goal of revolutionizing fashion. Fabrics never before seen in womenswear suddenly took center stage in his designs. See, for example, figure 6 which features a synthetic coat advertised in L’Officiel in 1968.

In Fifty Fashion Looks That Changed the 1960s (2012), Paula Reed writes:

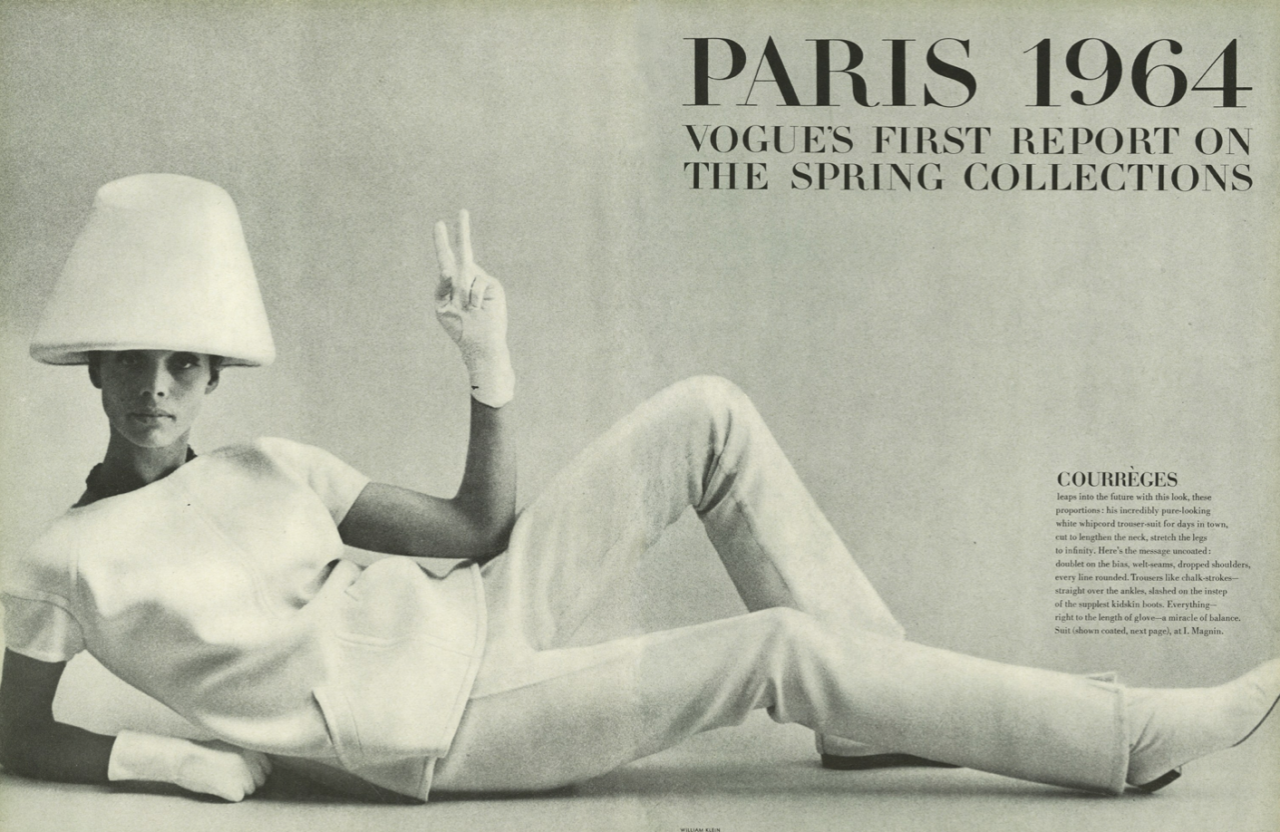

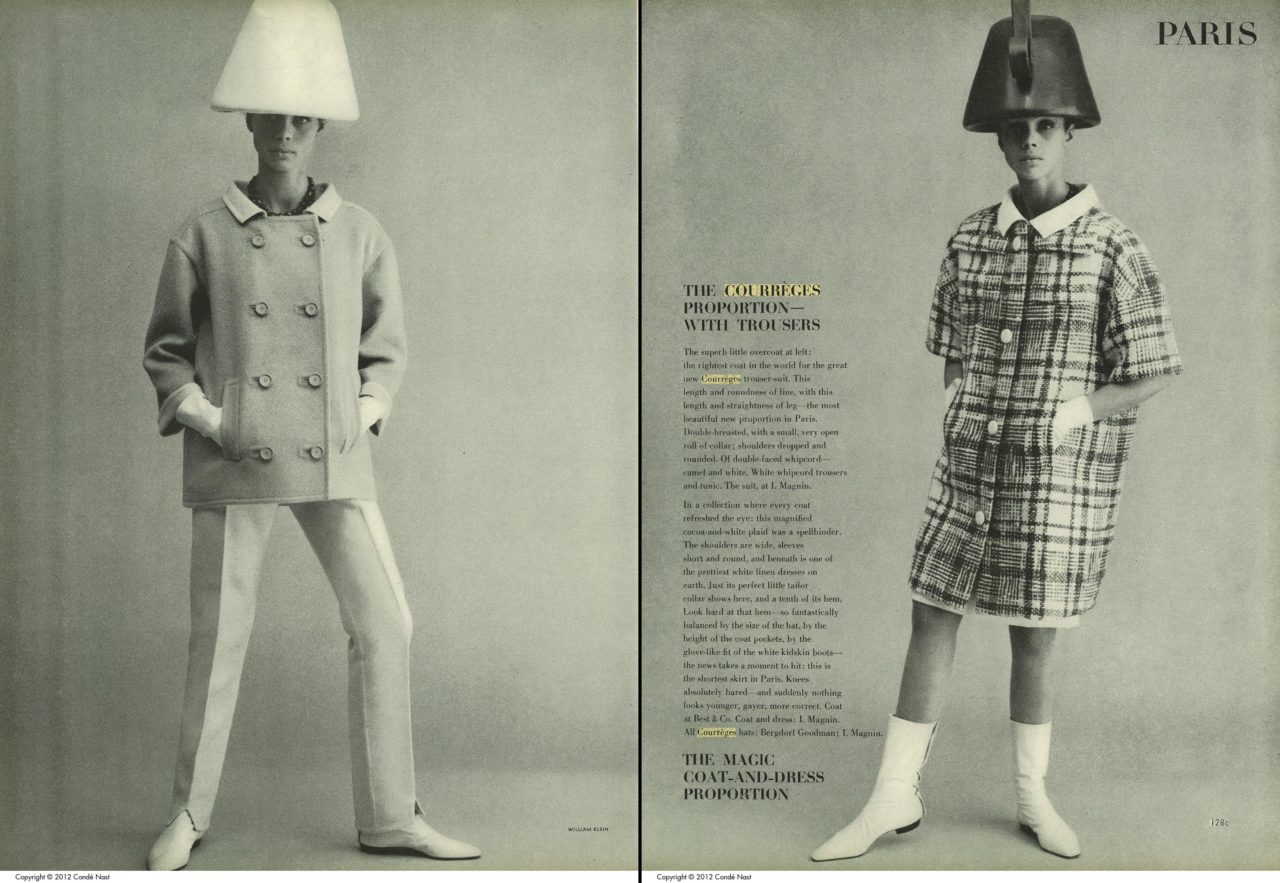

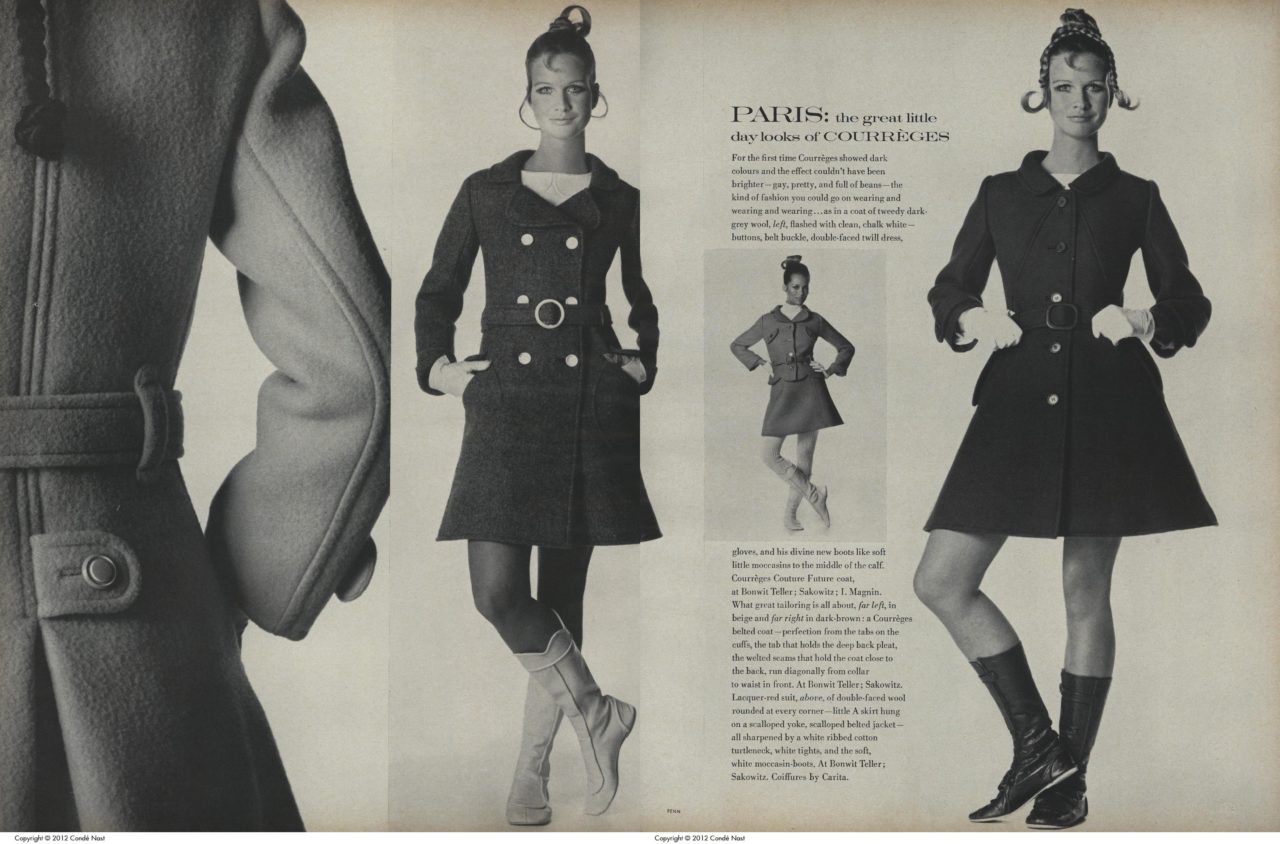

“His spring 1964 collection, with its linear mini dresses and futuristic tailoring, confounded the experts. The look was created using heavyweight fabrics such as gabardine that held a stiff, uncompromising shape. Moreover, he used materials hitherto unheard of in the couture atelier: metal, plastic and a cutting-edge innovation called PVC. Many of the outfits had cut-out panels, exposing backs, waists and midriffs, and shockingly they were also often worn without a bra.” (30)

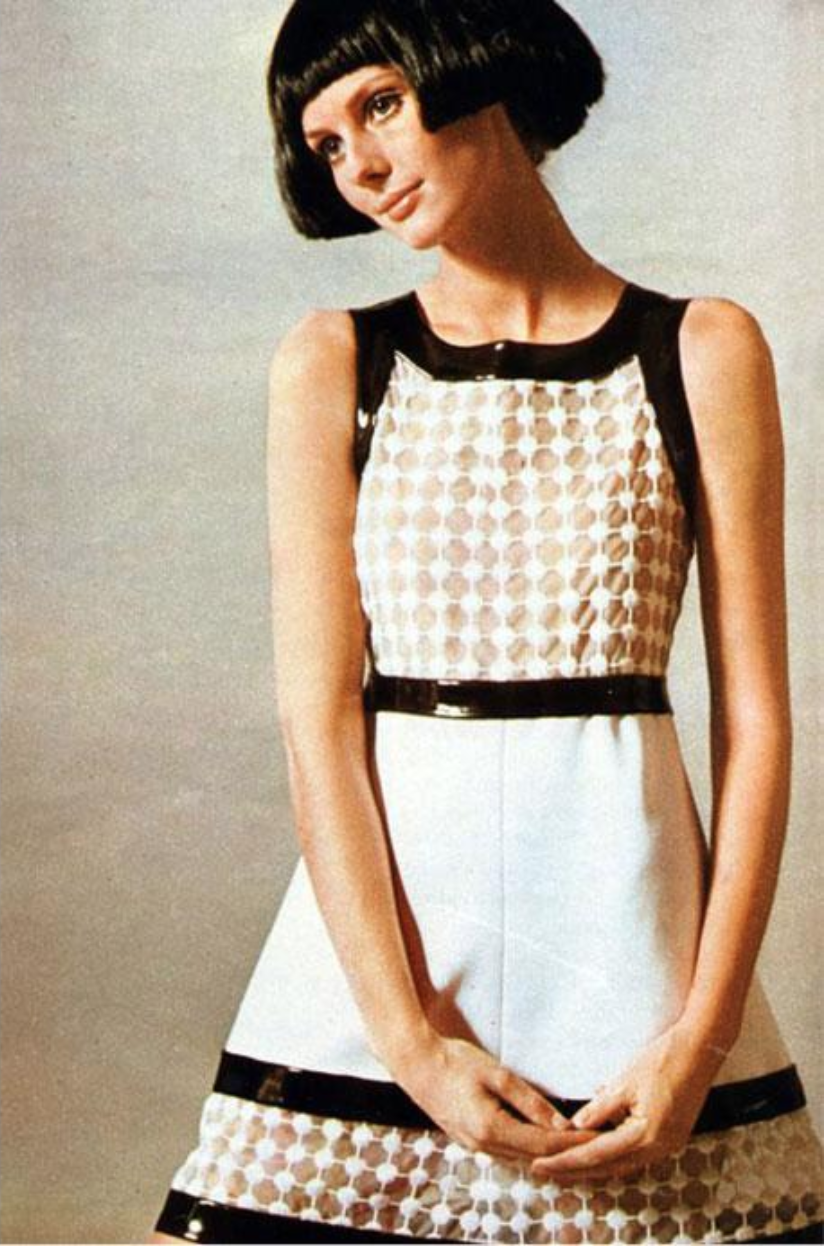

Figures 7 and 8 depict these heavyweight fabrics and stiff silhouettes from his 1964 spring collection on the cover of Vogue. Courrèges opted for a ‘youthful’ look, which he was fond of and based the majority of his designs around. The then-aged Coco Chanel watched these designs come to life with a skeptical eye, stating in 1966 that “This man is trying to destroy women by covering up their figures and turning them into little girls” (Guillaume 16). In 1972, Elle described Courrèges dresses as “the kind of dress a little girl would wear for her big sister’s wedding” (Guillaume 17). True to the criticism, Courrèges had taken inspiration from “the high plain yokes on little girls’ dresses, pinafores and dungarees” (Guillaume 17). Despite such commentary, Courrèges’ designs (Figs. 9-10) were both recognizable and highly sought after. In her MA thesis from the Fashion Institute of Technology (1988), Kathryn Ann Dwyer wrote:

“[Courrèges’] Spring Collection of 1964 made a dramatic impact on the fashion world. His space age baby doll designs overwhelmed the buyers because of their structure, uniqueness and sexiness. Ruth Lyman, a fashion editor covering this collection called it an ‘unforgettable revelation, a shuttering jolt into the present and the future. the tall bronzed model girls came out one by one in their perfectly cut coats and dresses and their immaculate pants outfits. But it was the extreme sexiness of the clothes which has us almost holding our breath with excitement. One had never seen anything quite like it before.’” (9)

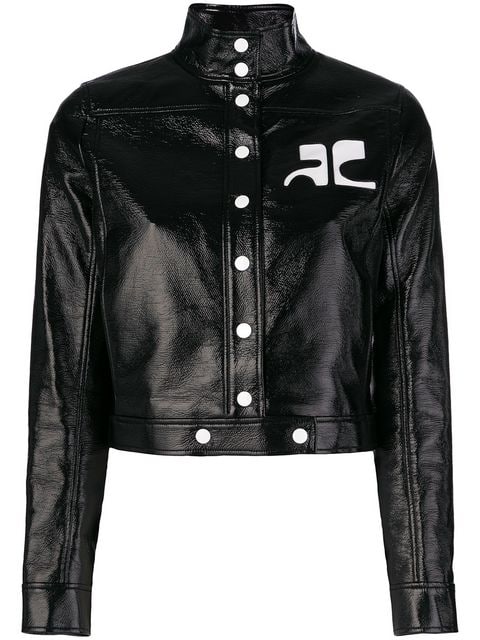

After a trip to America in 1965, the Courrèges discovered that their designs were being copied illegally, and they decided to come up with a logo to protect their brand. Coqueline explains: “we decided to intertwine our initials like the ones embroidered on linen in old-fashioned trousseaux. Our logo is strongly geometrical. The letters are in circles between the central axis. The initials have to be in the right place, which is different each time” (Guillaume 19). They began adding their design to the outside of all their clothes, thus incarnating a tradition which is still used widely in many Courrèges designs (Fig. 11).

Even though Coqueline was the behind-the-scenes creative, she occasionally dealt with press for the brand. During an interview for The New York Times (2001), Lisa Eisner and Roman Alonso asked Coqueline why the Courrèges aesthetic is still relevant; she responded: “because it’s stripped down to structure and purity. It’s pure, and it functions. It’s modern because it works.”

Courrèges’ coat-like dresses are pictured in a 1968 issue of Vogue (Fig. 12) titled “Fashion to Stimulate the World.” The designer’s iconic style continues to influence a variety of creatives in the fashion world today: In The History of Modern Fashion: From 1850 to 2010 (2015), Daniel James Cole and Nancy Deihl discuss how Courrèges’ designs fit in with the spirit of the time:

“Advances in space travel by both the United States and the Soviet Union promised a Space Age in the foreseeable future; the theme of space travel and the future was prevalent in popular culture, ranging from science fiction films, to home product design, to fashion.” (267)

The same futuristic approach can be seen among the fashion and art industries of today. The ideals that Courrèges stood for are still relevant, and continue to influence the work of fashion designers five decades later.

Fig. 4 - Emanuel Ungaro (French, 1933-). Vogue's Eye View: Fashion to Stimulate the World: The Inventive Savoir Vivre of Paris, Vol. 152, Issue 5, pg. 26-27 (Sep 15, 1968). Photographed by Irving Penn. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 5 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). L’Officiel, 1970. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 6 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). L'Officiel, 1968. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 7 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). Fashion: Paris 1964: Vogue's First Report on the Spring Collections, Vol. 143, Issue 5, pg. 1-2 (Mar 1, 1964). Photographed by William Klein. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 8 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). Fashion: Paris 1964: Vogue's First Report on the Spring Collections, Vol. 143, Issue 5, pg. 3-4 (Mar 1, 1964). Photographed by William Klein. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 9 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). Marie Claire, 1969. Source: Shrimpton Couture

Fig. 10 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). L'Officiel, 1969. Source: Shrimpton Couture

Fig. 11 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). Logo Bomber Jacket, 2000s. Source: FarFetch

Fig. 12 - André Courrèges (French, 1923-2016). Vogue's Eye View: Fashion to Stimulate the World: The Inventive Savoir Vivre of Paris, Vol. 152, Issue 5, Pg. 16-17 (Sep 15, 1968). Photographed by Irving Penn. Source: ProQuest

References:

- Cole, Daniel James, and Nancy Deihl. The History of Modern Fashion: From 1850 to 2010. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/932219920.

- Dwyer, Kathryn Ann. “Courrèges: The Last Couturier?,” MA Thesis, The Fashion Institute of Technology, 1988. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/80117644.

-

Eisner, Lisa, and Roman Alonso. “The White House: After Turning Fashion on its (White-Boot) Heel in the 60’s, Courreges is Back in Orbit.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Aug 19, 2001. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/92072544?accountid=27253.

- Guillaume, Valérie. Courrèges. New York: Assouline Publishing, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083132201.

- Reed, Paula. Fifty Fashion Looks That Changed the 1960s. London: Conran Octopus, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/829062212.

- “Vogue’s Eye View: Fashion to Stimulate the World: The Inventive Savoir Vivre of Paris.” Vogue, Sep 15, 1968, 87-117, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/897855990?accountid=27253.

- WWD Staff. “André Courrèges: Space Age Couturier.” WWD. Penske Media Corporation, 10 Jan 2016. https://wwd.com/fashion-news/designer-luxury/andre-courreges-space-age-couturier-10307711/