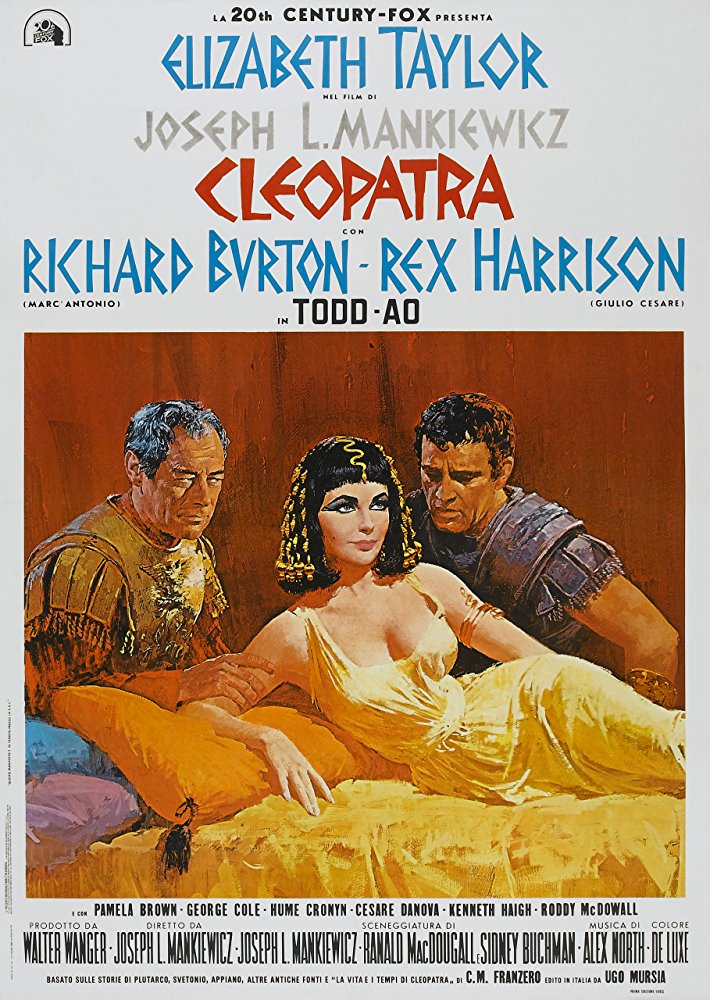

Cleopatra (1963)

Synopsis

Queen Cleopatra of Egypt experiences both triumph and tragedy as she attempts to resist the imperial ambitions of Rome.

Directed by

Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Release date

31 July 1963 (UK)

Costume Designer

- Nino Novarese [men]

- Renié [Irene Conley née Brouillet, women]

- Irene Sharaff [Elizabeth Taylor]

Studio

- Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation (as Twentieth Century – Fox)

- MCL Films S.A.

- Walwa Films S.A.

Source: IMDB

Film trailer

Introduction

The story of the 1963 film Cleopatra, starring Elizabeth Taylor, begins in the 1950s, when lavishly produced period films were Hollywood’s answer to the rise of television. Epic spectacles set in antiquity, filmed in widescreen Technicolor, seemed like a winning formula to lure audiences away from the small black-and-white screen at home and back into theatres. Samson and Delilah (1949), The Robe (1953), Ben-Hur (1959) and Spartacus (1960) were outstanding examples that all won Academy Awards for their costume designers. Conceived in 1958 at Twentieth Century Fox, Cleopatra is considered the last of the era’s ancient epics. [Although The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) was technically the last ancient epic to be released in this cycle, the long production time and the publicity surrounding Cleopatra made it more memorable (Burns).] Its troubled production and $44 million cost, which almost bankrupted the studio, discouraged filmmakers from attempting the genre until computer-generated imagery made it economically viable again. The equivalent in 2014 dollars is $338 million, making Cleopatra one of the most expensive films ever made (Susman).

After three years of shooting and re-shooting in London, Rome, Egypt and Spain, director Joseph L. Mankiewicz hoped to release two three-hour films, Caesar and Cleopatra and Antony and Cleopatra, but the studio insisted that he edit the footage into a single film. The version that premiered in New York in June 1963, over four hours long with an intermission in the middle, was released on DVD in 2006. After the premiere the studio made further cuts; the version that ran in theatres was only about three hours long (Burns). In this paper I will describe and analyze the costumes seen in the more complete DVD version, concentrating on the costumes of the leading character, Cleopatra.

About the Period Setting

The action of the film takes place between 48 B.C. and 30 B.C., in Alexandria, Egypt and in Rome. Cleopatra (born c. 69 B.C.) ages from twenty to thirty-nine during the course of the story. The first decision the film’s production designers faced was whether to represent Cleopatra’s dual cultural heritage and identity. Although she ruled as a female Pharaoh, Cleopatra was not descended from ancient Egyptian Pharaohs, but rather from conquering Greeks, who had arrived in Egypt with Alexander the Great about three hundred years before (“Cleopatra”).

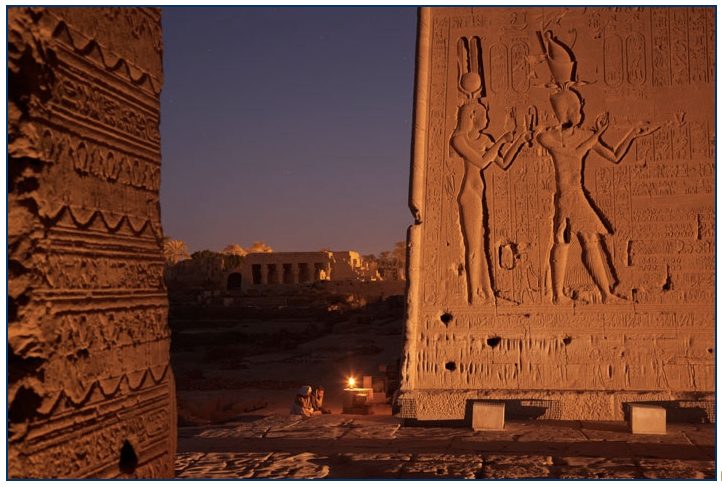

Fig. 1 - Cleopatra and Caesarion, relief sculpture. Temple of Dendera. Photograph by George Steinmetz. Source: National Geographic

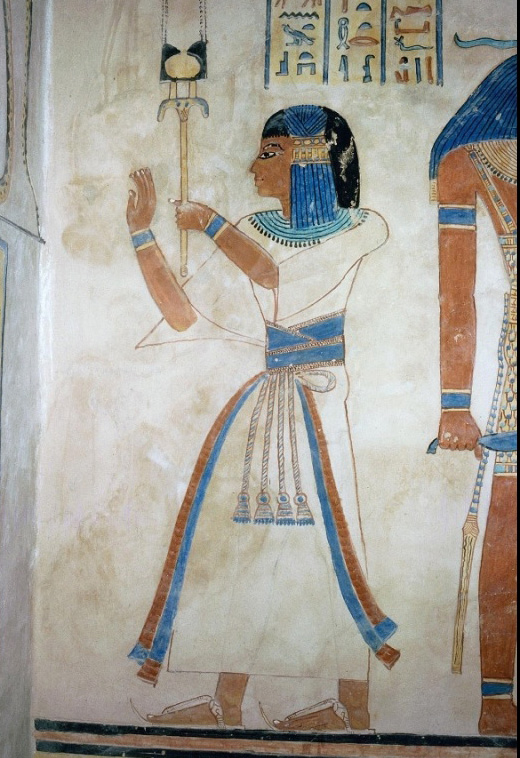

Fig. 2 - This tomb painting shows a white linen strap gown. Tomb of Sarenput II, ca. 1912 B.C. Aswan, Egypt. Source: Author

According to Robert LaVine, “to achieve historical accuracy in Cleopatra, research for the outfits was done from early Egyptian bas-reliefs, tomb paintings, and sculpture” (139). There are only two sculptures depicting Cleopatra surviving from her lifetime (C. Brown). One is a relief sculpture carved on the wall of an Egyptian temple (fig. 1). It shows her wearing a strap gown, the garment worn by women from the earliest periods of Egyptian history. The strap gown consisted of two pieces of linen sewn up the sides and suspended from the shoulders by means of straps made of folded linen, wide enough to cover the breasts. Although the strap gown could be decorated with embroidered beads in various colors, it was usually plain linen, in its natural color or bleached white, the material used for most ancient Egyptian costume (fig. 2). In the relief sculpture Cleopatra also wears a necklace called a broad collar, a long wig, and a ceremonial headdress with a sun disk and double feather enclosed in horns (Boucher 94-96).

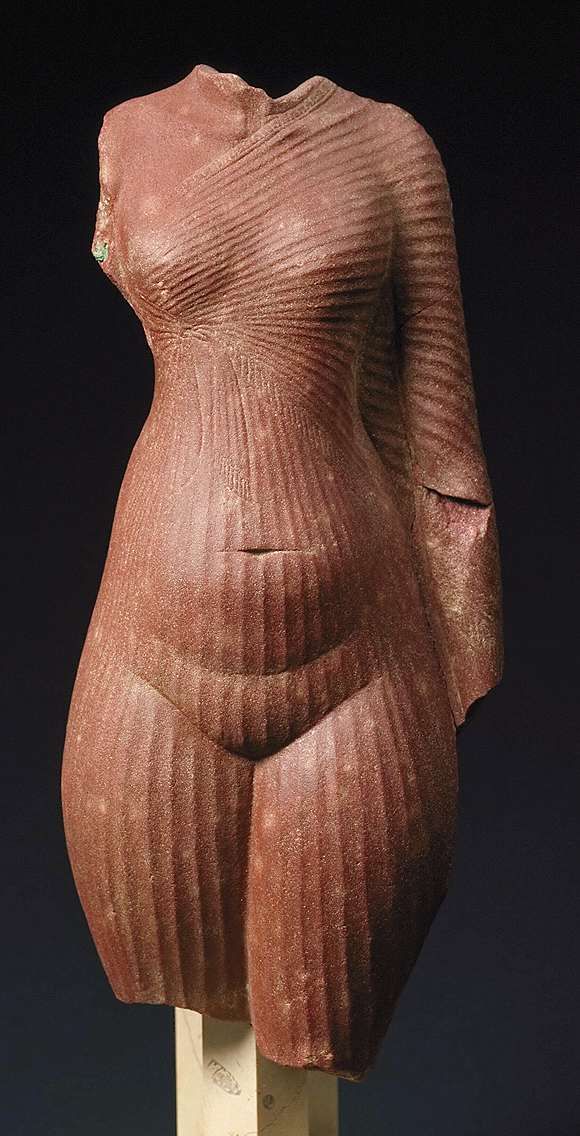

During the New Kingdom (1550-1070 B.C) a new garment called the kalasiris was introduced. The kalasiris was made of a single piece of linen wide enough to span the outstretched arms of the wearer, and long enough to entirely cover the front and back of the body; a slit in the center allowed it to be put on over the head; the sides were stitched together and the extra width pulled up into a knot at the center or held in place by belts. To help the garment fit the body more closely, the kalasiris could be finely pleated or crimped (fig. 3). Only one other garment was worn by ancient Egyptian women, and that was reserved for the highest-ranking members of the royal family. The royal haïk was a single wide piece of the finest, most transparent linen, draped diagonally around the body (fig. 4). The Pharaoh’s traditional ceremonial costume included various elaborate crowns and headdresses (Boucher 94-96).

Since Cleopatra was actually Greek, the film’s costume designers could have chosen to dress her in a Greek chiton (two pieces of wide linen, stitched partly up the sides and pinned together at the shoulders) and himation (a large, rectangular shawl) instead of Egyptian costume (S. Brown 25). The other sculpture that portrays Cleopatra during her lifetime, probably made in Rome while Cleopatra was there in 45 B.C., shows her wearing a Greco-Roman hairstyle (fig. 5). However in the film, apart from the characters’ visit to Alexander the Great’s tomb, there is little evidence of Greek culture. Cleopatra’s palace and costume are Egyptian in style.

Fig. 3 - A New Kingdom queen wears a white linen kalasiris. Tomb of Queen Nefertari, ca. 1200 B.C. Thebes, Egypt. Source: Author

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Statue of an Amarna Princess, ca. 1360 B.C. Pink quartzite; 29 cm. Paris: Musée du Louvre. Tell el Amarna, Egypt. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. Portrait bust of Cleopatra, ca. 45 B.C. Berlin: Altes Museum. Source: Wikipedia

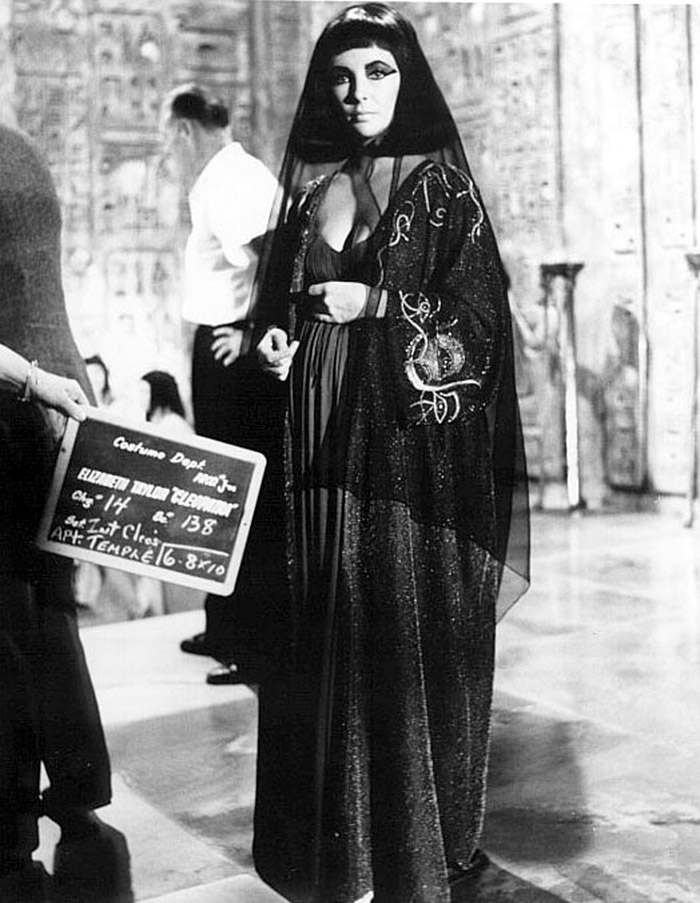

About the Costume Design

Since Cleopatra has so many costumes – a record-setting sixty-five for a single character in a feature film, of which only thirty-eight are seen in the four-hour cut (fig. 6), I have divided the costumes into categories and only included illustrations of the most important. [Edward Maeder writes that this figure of sixty-five costumes does not include forty that do not appear in the film, but I counted only thirty-eight in the four-hour cut. Therefore there were probably sixty-five total, with twenty-seven cut out of the film (Maeder 50).]

The Strap Gowns

The film opens with Julius Caesar (Rex Harrison) pursuing the rival Roman general Pompey to Egypt, which is ruled jointly by the young Pharaoh Ptolemy and his older sister Cleopatra. Cleopatra’s first appearance in the film is based on an account by the Roman historian Plutarch. She has herself rolled up in a carpet and smuggled in to meet Caesar in secret, since she is at war with her brother and hopes that Caesar will support her efforts to become Egypt’s sole ruler. The costume Cleopatra wears in this scene is the first of many of a type that appears throughout the film. It is a fitted sleeveless dress, with a V-neckline, based on the strap gown. This first one is red and fitted at the waist, with a skirt open at the sides to reveal a white, pleated under-layer (fig. 7). Both the red and the white fabrics look like lightweight silks, though they may in fact be synthetics.

There are over a dozen variations of this type of costume in the film, worn alone or under another garment as part of an ensemble. Some are loose-fitting or with a drawstring waistline, and are evidently meant to be nightgowns, but most are fitted and have lines of stitched horizontal or vertical pleats on the bodices. Some of the best examples are the sky blue one worn under a long, sheer white vest embroidered with lotus motifs (fig. 8), the orange one slit at the sides to reveal a sheer pair of pants underneath (fig. 9) the yellow one worn with a narrow white scarf hanging from the left shoulder (fig. 10) and the dark green one with a red and white shawl hanging from the right shoulder and tucked into a belt at the opposite side (fig. 11). A couple of variations have long fitted sleeves, like the bright green one seen in the second half of the film (fig. 12).

Fig. 6 - Left on the cutting room floor: Costume change no. 14 does not appear in the film. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 7 - Cleopatra’s first appearance in the film, wearing a red and white “strap gown.”. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 8 - A sky-blue strap gown with a long embroidered vest. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 12 - Cleopatra and Mark Antony (Richard Burton), in her bedroom. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 9 - An orange strap gown open at the sides over matching pants. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 10 - Cleopatra wears this yellow strap gown while she is visiting Rome. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 11 - At the window of Caesar’s villa near Rome, with his library in the background, Cleopatra wears a dark olive green strap gown with a red and white draped shawl. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

The Royal Haïk

In one early scene Cleopatra wears a dress draped over her right shoulder, leaving the left shoulder bare (fig. 13), which is probably based on the royal haïk. Despite the flowing drapery – the material looks like an undyed, silk crepe georgette or chiffon — underneath there is a fitted foundation. There is only one costume of this type in the four‐hour long cut of Cleopatra.

The Kalasiris

Another type of costume introduced during the early scenes is a long-sleeved, flowing dress based upon the kalasiris. The first one that we see is of turquoise silk, trimmed with gold braid and with a high slit up one side, revealing Cleopatra’s leg and golden sandals (fig. 14). In this scene she is relaxing on what looks like a terrace off her bedroom, so the scene establishes that this type of costume is informal and private in character. Two others are in shades of purple silk, with drawstring necklines and metallic embroidery.

The Open Kalasiris

Other versions of the kalasiris are open all the way down the front, like a robe. When made out of a sheer silky fabric and worn over a matching loose-fitting dress or nightgown, the open kalasiris forms a negligée ensemble, such as the golden orange one Cleopatra wears in the second half of the film, when she is awakened in the middle of the night and told that her lover Mark Antony has married another woman (fig. 15). As she flies into a rage and begins attacking Antony’s clothes with a dagger, the viewer sees the silver bead embroidery on the back of the robe and the black and white cranes embroidered on the sleeves (fig. 16). This costume was kept by Elizabeth Taylor and sold at auction after her death in 2011 (fig. 17).

Fig. 14 - Cleopatra with two of her attendants, the Egyptian Charmian (left) and the Chinese Lotus (right). Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 15 - The “open kalasiris” over a loose dress forms a negligée ensemble of nightgown and robe. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 16 - Cleopatra is enraged that Antony has married another woman. The back of her robe is embroidered with beads and black and white cranes. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

The Ensembles

As the film progresses, Cleopatra increasingly wears two garments layered one over the other, with increasingly elaborate wigs, jewelry and makeup. Sometimes the two garments match; sometimes they contrast in color or texture. In the scene where Caesar and Cleopatra visit Alexander the Great’s tomb, she wears a strap gown and an open kalasiris in matching violet silk satin, with one of her most elaborate golden headdresses (fig. 18). Earlier in the film there had been a reference to Caesar wearing his finest armor to visit the tomb, and he wears it again in this scene, so Cleopatra may be more elaborately dressed for the same reason, to show respect for Alexander the Great. Another striking ensemble is worn during the highlight of the film’s second half, the arrival of Cleopatra’s barge in Greece, where she has gone to meet Mark Antony. It consists of a dark blue strap gown with a bright blue open kalasiris, embroidered with golden sequins and swirling dark blue snake motifs (fig. 19). Later that evening, when she entertains Antony aboard the barge, she wears a similar ensemble, the two garments in matching white. During the second half of the film, this combination of garments becomes something of a formula (fig. 20). One ensemble is a red strap gown with a pink open kalasiris, another a blue-gray strap gown with a mauve open kalasiris, embroidered with a reptilian scale pattern, and yet another is an orange strap gown, embroidered with black snakes along the midriff, worn with a gray open kalasiris embroidered in silver lotuses.

Another type of ensemble is more rare. It consists of a long-sleeved, fitted dress with a high neckline, and some kind of scarf, shawl or coat on top. There are three variations in the film: a dress in violet silk, with a narrow red scarf, embroidered in gold with a snake motif, draped over the head (fig. 21). Cleopatra wears the second example when she is aboard her ship, during the naval Battle of Actium: a dark blue dress, with a heavy beige coat lined entirely in leopard fur, and a blue crown (fig. 22). Another example of the long-sleeved fitted dress with the high neckline is bright red, and worn with a black hooded cape lined in the same red silk and trimmed with gold braid.

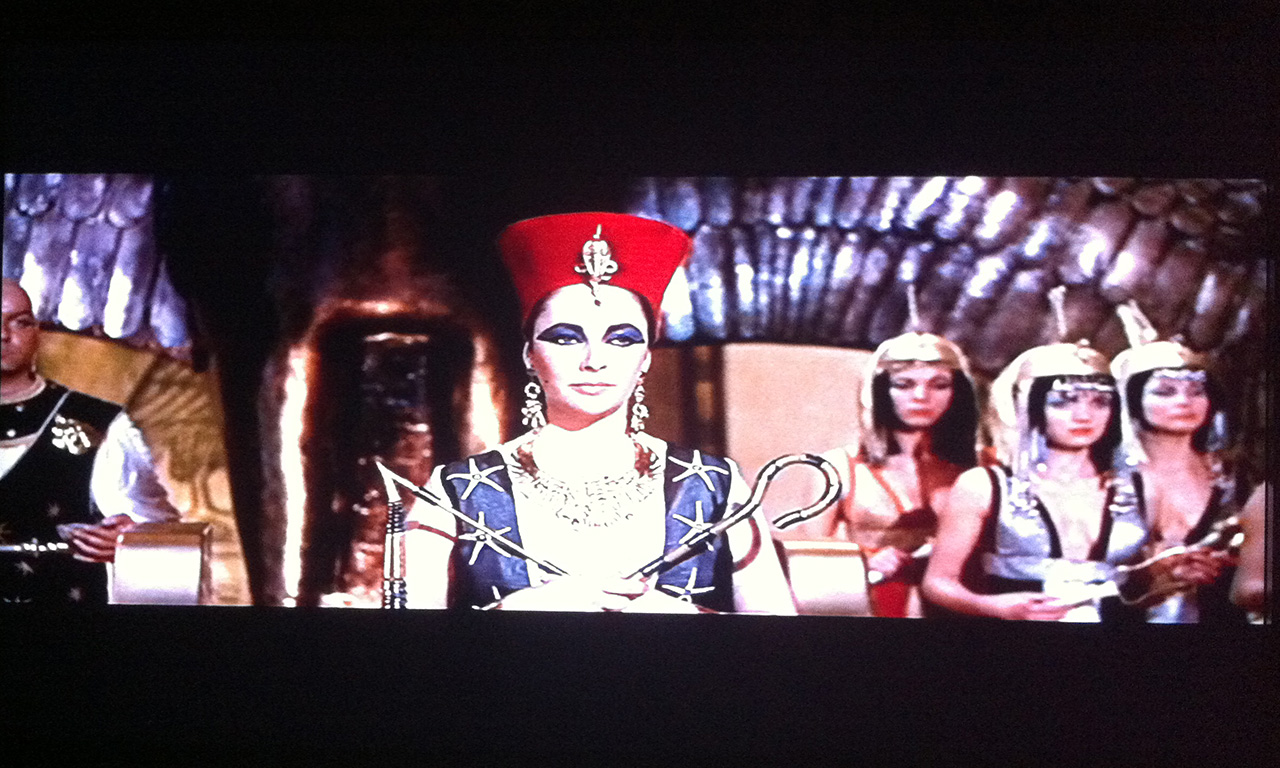

Ceremonial Costumes

Cleopatra wears four costumes that are ceremonial, the first when Caesar crowns her sole ruler of Egypt. The editing jumps from a long shot of the crowded throne room to close-ups of Cleopatra, so the costume is barely seen, although we do see her red and white double crown, representing the union of lower and upper Egypt. [The Metropolitan Museum has a sculpture of a goddess wearing the double crown, dating from the Intermediate Period (c. 1070-664 B.C.)]. Later, when she is again sitting on her throne, she wears a white strap gown under a long sleeveless black vest embroidered with white stars, and a similar crown.

After the intermission, when we first see Cleopatra at the start of the second half of the film, she is performing a ceremony before a statue of Caesar, and wears an ensemble consisting of a dark purple strap gown and an open kalasiris elaborately embroidered in radiating black and white stripes. What makes this costume ceremonial, however, is the even more elaborate silver headdress (fig. 23).

The most spectacular ceremonial costume, however, is the golden “Phoenix” ensemble worn for Cleopatra’s triumphal procession into Rome atop a huge black sphinx (fig. 24) Over a fitted dress of the strap gown type, embroidered in gold and with a pleated gold skirt, she wore a cape made of gold-painted strips of leather embroidered with gold bugle and seed beads. Together with the crown, the Phoenix cape made Cleopatra look like a golden bird-goddess. It is the only costume that appears twice in the film, the second time at the very end (fig. 25).

Wigs, Headdresses and Crowns

Cleopatra’s wigs and headdresses are very important elements of the costuming in this film. Her first wig is an unadorned shoulder-length pageboy with short bangs (fig. 7). The second one falls in three tiers of graduated length to her shoulders. Gradually the wigs grow more complicated, and they acquire decorative golden beads and headdresses laid on top. In scenes that take place in Cleopatra’s bedroom, we can see her attendants styling her many wigs, which are displayed on a special piece of furniture. The viewer picks up on the fact that Cleopatra wears wigs for the sake of fashion; underneath them she has her own long, dark hair though in keeping with Hollywood practice, Cleopatra’s “natural” hair is probably also a wig worn by Taylor over her own hair.

The headdresses in the film are of two types – decorative and ceremonial. An example of a decorative headdress is the one adorned with white flowers, probably made of silk (fig. 10). One of the most elaborate seen early in the film is the golden one worn to visit Alexander the Great’s tomb (fig. 18). The most elaborate headdress in the film is the one worn with the Phoenix ensemble (fig. 26). Like the Phoenix cape, these headdresses and crowns were probably made of woven, painted and embroidered leather.

Jewelry & Other Accessories

On several occasions in the script there are references to “Egyptian gold,” and to the Romans’ desire for Egypt’s riches. So it is not surprising that even in the early scenes when she is dressed relatively simply, Cleopatra always wears some jewelry, and it is always of gold. With her first costume she wears cuff bracelets at both wrists, which will remain nearly constant throughout the film, and a golden dagger tied to her belt (fig. 7). Near the end of the film, when her life is again in danger, we will see this dagger at her waistline again.

Her one-shouldered royal haïk costume is accessorized with a gold bracelet on her left upper arm, long gold earrings, and a large gold brooch under her right breast (fig. 13). She will often wear heavy gold earrings even when she also has a gold-decorated wig or headdress. When she leaves Rome and returns to Egypt after Caesar’s death, Cleopatra wears an especially notable piece of jewelry over her daringly low-cut strap gown: a golden chain acting as a belt under her breasts, fastening in the center with a buckle in the form of a coiled snake (fig. 27). At the start of the second half of the film, dialogue calls attention to a necklace she has had made out of the gold coins issued by the Romans with Caesar’s face on them. Cleopatra wears it with three different costumes and she tells Mark Antony that she wears it always, even to bed, as we see in a later scene (fig. 28). However once her relationship with Antony begins, the necklace disappears, signaling that a new man has replaced Caesar in her life.

The second time we see Cleopatra on her throne in ceremonial costume, she wears more jewelry–long heavy gold earrings and a gold necklace in the form of the wings of Horus, the sky god (fig. 29). This conveys the impression that she has grown older and more powerful. Near the end of the film the heavy jewelry, gold-decorated wigs and golden headdresses diminish, and Cleopatra returns to a simpler style, just before the spectacular “Phoenix” costume reappears at the end.

Makeup

Even in the early scenes of the film, Cleopatra’s eyes are surrounded by black eyeliner, with the upper line extended onto her temples, and her brows heavily drawn in. As the film continues her eye makeup gets heavier, with the whole area between her extended eyeliner and brows shadowed in blue or green (fig. 30). This makeup is inspired by ancient Egyptian sources and the film makes it clear that makeup is important to Cleopatra. In one scene, while her servants attend to her wigs, she sits at a table practicing her makeup techniques, or trying out new ones, on sculpted busts (fig. 31). Her makeup is even heavier when she wears ceremonial costume, when the eye shadow glints with a metallic sheen.

Nudity and Drapery

Cleopatra is shown nude or nearly so in two early scenes that establish that she is a sensuous and alluring woman. We see her near the round bathing pool in her bedroom at the palace in Alexandria, lying face down on a table as an attendant massages her back. A towel covers half of her body lengthwise, and on her head she wears a kerchief folded in the style of a nemes, the headdress worn by Pharaohs and Sphinxes (fig. 32). Soon afterwards she exchanges angry words with Caesar while lying on a bed, wearing only a piece of sheer violet silk. During the second half of the film she has another nude scene, bathing in the pool.

Fig. 18 - Caesar wears his best armor and Cleopatra a purple silk ensemble and an elaborate headdress to visit the tomb of Alexander the Great. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 19 - Cleopatra wears her necklace of gold coins with Caesar’s image. Elizabeth Taylor’s deep suntan is visible at the neckline With this blue ensemble. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 20 - This elaborate costume of a white strap gown, sheer vest with gold-embroidered serpentine motifs, beaded wig and gold headdress is only seen for a few seconds on the screen. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 21 - Cleopatra standing at the door to Caesar’s villa near Rome. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 22 - At the Battle of Actium, Cleopatra wears a blue fitted dress, leopard-lined coat, and the Pharaoh’s blue crown of war. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 23 - With her necklace of Caesar coins; a statue of Caesar is in the background Cleopatra in ceremonial costume. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 24 - The “Phoenix” ensemble is worn for Cleopatra’s triumphal entry into Rome with her son Caesarion. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 25 - The “Phoenix” ensemble at the end of the film. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 26 - The headdress of the Phoenix ensemble was auctioned in 2011. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Business Insider

Fig. 27 - Cleopatra leaves Rome under cover of night following Caesar’s assasination. Elizabeth Taylor will later pose in this costume for Vogue (see Fig. 37). Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 28 - Cleopatra sleeps with her heavy Caesar coin necklace on. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 29 - Cleopatra in ceremonial costume, wearing the red crown of Lower (northern) Egypt with the uraeus serpent symbol in the center, and holding the crook and the flail. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 30 - Cleopatra’s heavily made-up eyes in one of the film’s early scenes. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 31 - While she practices her makeup techniques Cleopatra’s attendants work on her wigs. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 32 - Cleopatra gets a massage near her bathing pool, while Greek musicians and poets entertain her. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

About the Costume Designers

The person most responsible for the look of Cleopatra was production designer John De Cuir, who envisioned the seventy-nine sets that represented such historic sites as the harbor and palace at Alexandria, the Roman Forum and Caesar’s villa near Rome. It was De Cuir’s decision to make the Alexandria exteriors in a Greek style and the interiors, where most of the film’s action takes place, in an Egyptian style, reflecting Cleopatra’s dual cultural heritage.

Creating the costumes for Cleopatra was a huge task. The British theatrical costume designer Oliver Messel, who had costumed the 1945 film Caesar and Cleopatra, was originally hired to design the costumes for the principal characters (LaVine 139). Messel’s costumes were used when the film began shooting under director Reuben Mamoulian at Pinewood Studios in London in September 1960, but after Elizabeth Taylor became seriously ill, the London production was shut down, and it was decided to move production to Cinecitta Studios in Rome. In the meantime the director was replaced with Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who rewrote the entire script, and most of the London footage was scrapped, at a cost of seven million dollars. Messel’s elaborate costumes (fig. 33) were abandoned along with the London sets. The job of designing the costumes was then divided among three designers. According to the documentary that accompanied the DVD release, over 26,000 costumes were made in total (Burns). The Italian designer Vittorio Nino Novarese designed the men’s costumes and Hollywood studio designer Renie Conley designed the women’s. Irene Sharaff was hired to design Elizabeth Taylor’s costumes, with Vivienne Zavitz (later Vivienne Walker) responsible for her hairdressing and Albert De Rossi for makeup. Although neither was credited, Joan Joseff designed and/or made Cleopatra’s jewelry, and Wah Chang contributed to the design of the headdresses (IMDB).

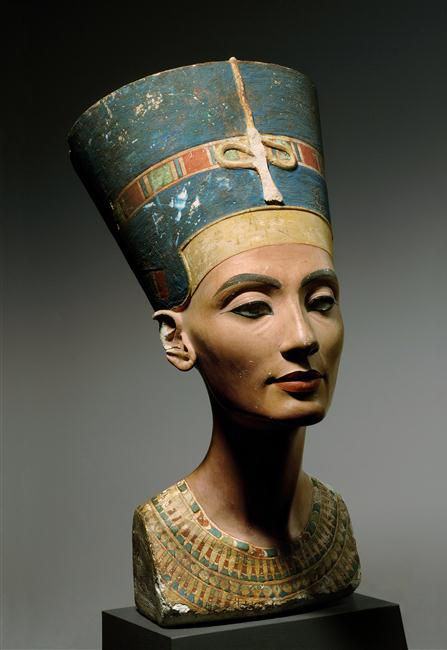

Irene Sharaff (1910-1993) started her career designing for the New York stage. In 1942 she was brought to Hollywood by the MGM producer Arthur Freed to design costumes for period musicals, such as Meet Me in St. Louis (1944). At the time of her work on Cleopatra, she had won two Academy Awards (for The King and I in 1956 and for West Side Story in 1961) and was working as a freelance designer (IMDB). Sharaff took her cue from De Cuir’s production design, and chose to portray Cleopatra as an Egyptian rather than a Greek. Many of Sharaf’s costumes were interpretations of the strap gown and headdress worn by Cleopatra in the sculpture made during her lifetime. Standing next to her in this sculpture (fig. 1) is Caesarion, her son by Caesar, whom she had made co-ruler. He is shown wearing the double crown representing dominion over Upper and Lower Egypt. This is the same crown that Cleopatra wears with her first ceremonial costume (fig. 34). Since these crowns were worn without a wig underneath, in these ceremonial scenes Cleopatra resembles the famous painted sculpture of Nefertiti (fig. 35), consort to the New Kingdom Pharaoh Ahkenaten. The relief probably inspired Sharaff’s main concept—that Cleopatra should wear fitted strap gowns—as well as the details of her ceremonial head-dresses, but it only provides so much information. From tomb paintings (figs. 2-3), Sharaff would have learned that most of the color and pattern in ancient Egyptian costume came from jewelry and accessories. LaVine writes that Sharaff’s costumes were “gorgeously decorated with superb reproductions of authentic Egyptian jewelry and rich trimmings of jewel-set gold embroidery” (245). Sharaff and the jewelry designer Joan Joseff must have studied objects such as the gold bracelet in the form of two coiled snakes (fig. 36).

By the end of 1961, Cleopatra was more than half completed, though costs were spiraling out of control. Edward Maeder writes that the production was “gargantuan,” and “its costumes were a significant part of the budget” (50). The goal of the costume designers, like that of everyone involved, was not only to tell the story of Cleopatra, Caesar and Antony but to create a spectacle that was so magnificent that it would prove irresistible to audiences, and make good on the studio’s investment. Another goal that was considered essential to the film’s box-office success was to make the most of its star. Audiences expected the beautiful Elizabeth Taylor to look even more beautiful as the legendary Cleopatra. Joseph L. Mankiewicz reassured studio executives that he was “making a great movie that would draw massive audiences” (Burns).

Fig. 33 - Elizabeth Taylor in one of Oliver Messel’s costumes. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 34 - Cleopatra wearing the red and white crowns. Cleopatra, 1963. Source: Author

Fig. 35 - Thutmose (Egyptian, 14th century B.C.). Portrait of Queen Nefertiti, ca. 1345 B.C. Limestone and stucco; 48 cm (19 in). Berlin: Neues Museum. Source: RMN

Fig. 36 - C. 40 B.C Gold bracelet in the form of coiled snakes. . Photograph by Kenneth Garrett. Source: National Geographic

Historical Accuracy

The historical accuracy of Cleopatra’s costumes is not easy to determine, since nobody knows for sure what Cleopatra looked like or how she dressed. Given her family’s Greek ancestry and language, she most likely dressed in Greek costume, and in ancient Egyptian costume for ceremonial occasions only. However, this mixture of styles might have confused and disappointed audiences, and in any case it was not an option for Sharaff. Even before she joined the project, the filmmakers had decided to surround Cleopatra with Egyptian splendor. Comparing the costumes to Egyptian art, it is evident that she based many of them on Egyptian garments. Cleopatra’s sleeveless, fitted dresses are inspired by the strap gown, her one-shouldered dress is based upon the royal haïk, and her loungewear and the outer garments in her ensembles were based upon the kalasiris. The wigs, headdresses and crowns were designed with care. However it is inaccurate for Cleopatra to be shown sleeping with what is supposed to be her own long, dark hair; an ancient Egyptian would have had a shaved head (Boucher 94-98).

It is also evident that Sharaff departed from Egyptian costume when it suited her purpose. She chose not to use white linen, and we can understand why. Linen is not suitable for costume purposes because of its tendency to wrinkle, and sixty-five costumes in white linen, or even the thirty-eight that survived the editing process, would have been monotonous for the audience to see. Instead she chose to interpret Egyptian garments in colorful silks (or synthetics that photographed like silks), and to make all of the jewelry in gold. She also departed from the proportions and forms of the garments, occasionally adding long sleeves to the strap gown and slashing the kalasiris open down the front. Some of her designs, like the long-sleeved fitted dresses with high necklines, or the long vests, have no basis whatsoever in Egyptian, Greek or Roman costume.

Possible reasons for these departures and inventions are to provide a richly varied spectacle for the audience, and to show Elizabeth Taylor’s voluptuous figure to best advantage. As well as alluding to Cleopatra’s royal status, bringing out the color of her famous violet eyes was probably the reason that eight of the thirty-eight costumes are in shades of purple. Sharaff did not seem much influenced by contemporary fashion. As Maeder points out, Cleopatra’s makeup emphasizes the eyes and subordinates the lips, as in Sixties fashion generally. Some of the wigs do resemble fashionable hairstyles of the time, but the fitted, cinched waistlines of most of the costumes resemble the fashions of the mid-1950s more than those of the early 1960s.

Sharaff was more interested in furthering characterization and heightening the drama of the story. For example, she probably chose red for Cleopatra’s first costume because red had already been established in the film as a color associated with the Romans, so from the first Cleopatra is allied with Caesar. Sharaff was known for her sense of color and for attention to detail, both of which are evident in her designs for Cleopatra. Most of the outer garments are decorated with embroidered motifs taken from the sources Sharaff studied. The motif that recurs most often is the serpent. Sharaff may again have taken her cue from De Cuir’s production design, because the large door handles to the audience hall in Cleopatra’s palace are in the form of dramatically coiled serpents (fig. 13). The serpent can be seen as a reference to the uraeus that appeared on royal crowns, a symbol of the snake goddess who protected the Pharaoh’s family. [See the statue of King Sahure from Dynasty V, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.] It appears on Cleopatra’s crowns and headdresses, but the use of so many serpent motifs on her garments also prefigures the manner of her death.

Influence on Fashion

Cleopatra had an influence on fashion even before it was released. On July 13, 1962, Charlotte Curtis wrote in the New York Times that fashion editors and designers were reporting “real fashion excitement” about the film:

“Cleopatra,” still unreleased but already a widely publicized extravaganza, presents an Egyptian look from head to toes. Eyes are heavily kohled. The clothes, designed by Irene Sharaff, one of the few costume designers fashion people admire, are slinky, wildly colored, and exceedingly ornate. Head- dresses are large and angular. Jewelery, as ornate and colorful as the costume, is heavy. This film has already influenced virtually every division of the fashion industry of America from the manufacturers of black eye shadow and mascara, to the jewelery and shoe designers.

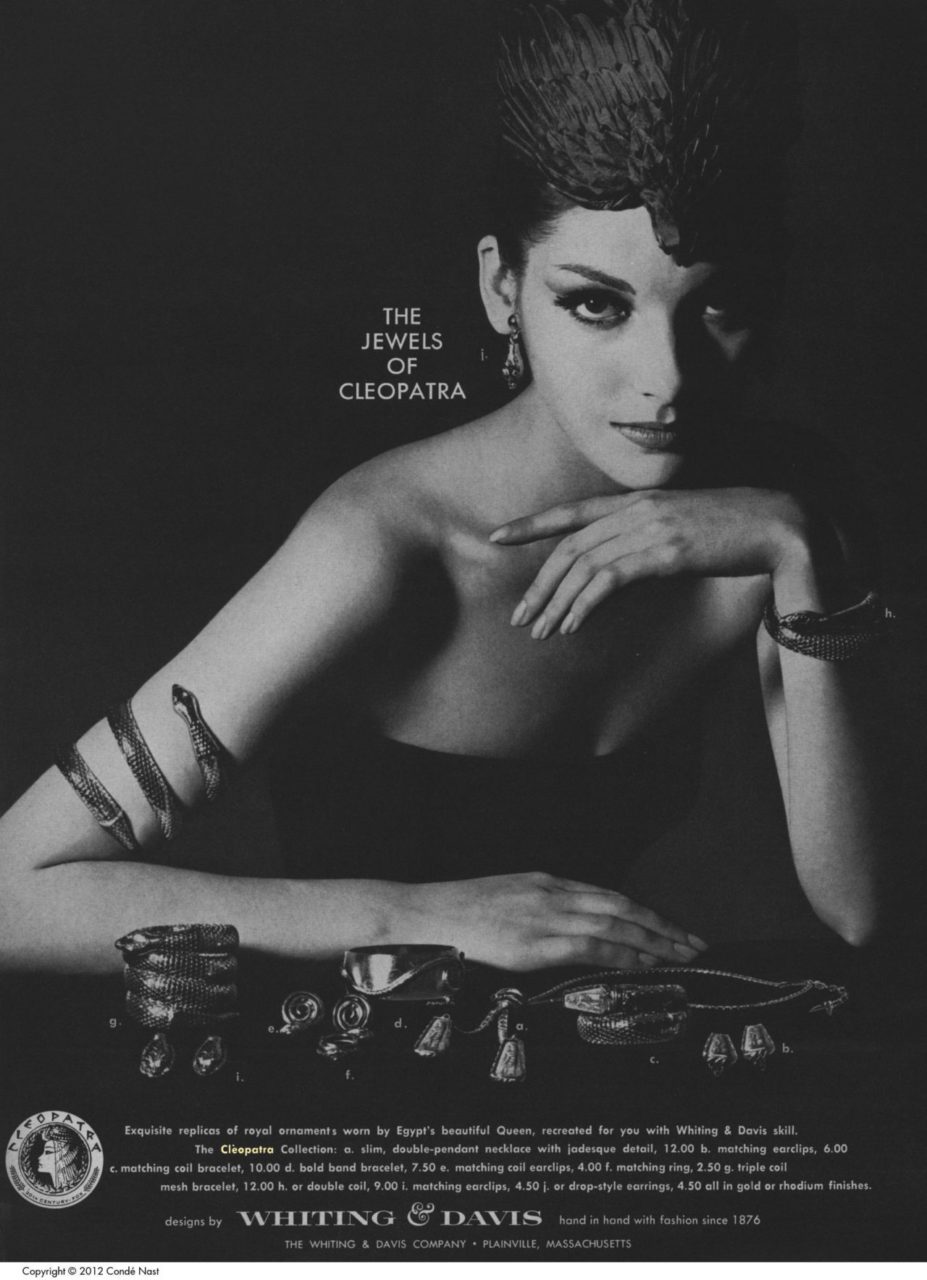

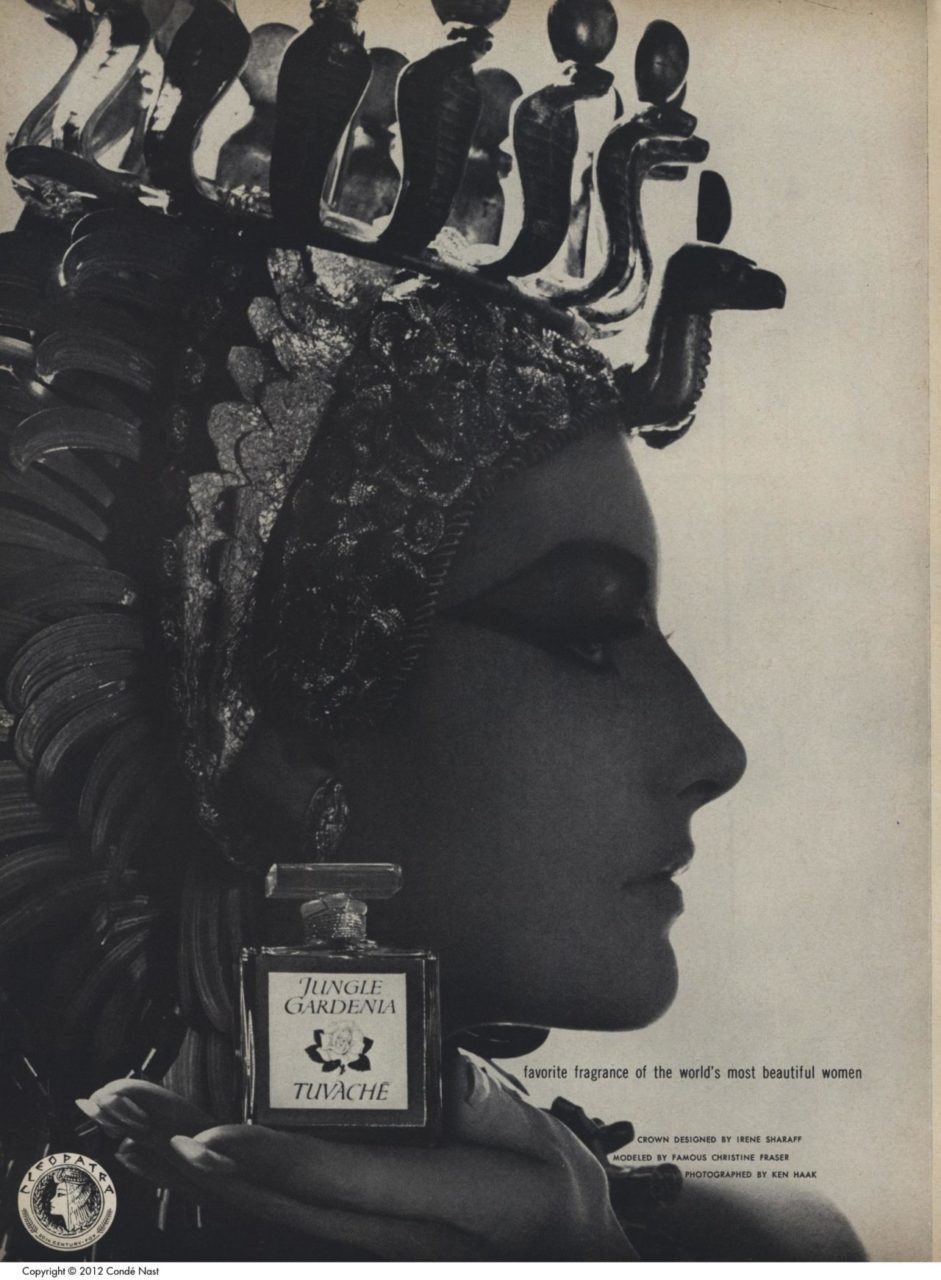

Even earlier, Vogue fueled the fashion world’s interest in the film by sending photographer Bert Stern to Rome to shoot a portrait of Elizabeth Taylor in one of her Cleopatra costumes and makeup (fig. 37) for their January 15, 1962 issue. Without the wig that accompanies the dramatically low-cut, long-sleeved strap gown in the film (fig. 27), the costume looks like it could be a contemporary evening dress, though an unusually daring one. Two months later Vogue gained access to the film’s sets in Anzio, Italy, where the Alexandria exteriors were shot, for a photo shoot featuring Italian fashion (fig. 38). The film’s most direct influence was seen in accessory design (fig. 39) and in the cosmetics and fragrance industry. In its April 1, 1962 issue Vogue recommended Revlon’s “Sphinx Kit,” to get the Cleopatra look. After the film’s release, one ad sanctioned by Twentieth Century Fox, for Elizabeth Taylor’s favorite gardenia perfume, featured a photograph of a model wearing Cleopatra’s golden headdress (fig. 40).

Fig. 37 - Photographed in one of her costumes for Cleopatra by Bert Stern Elizabeth Taylor. Vogue, Jan. 15, 1962, p. 41. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 38 - Photographed in one of her costumes for Cleopatra by Bert Stern Elizabeth Taylor. Vogue, Jan. 15, 1962, p. 41. Source: Vogue Archive

Fig. 39 - ” Whiting & Davis ad “The jewels of Cleopatra. Vogue, August 1, 1963, p. 24. Source: Vogue Archive

Fig. 40 - “Jungle Gardenia” perfume ad. Vogue, August 1, 1963. Source: Vogue Archive

Without a doubt the public’s interest in the film was also due to the drama of Elizabeth Taylor’s personal life. First, during the film’s first shoot in London in the fall of 1960, there was the illness that nearly killed her and that shut down production. An emergency tracheotomy had to be performed to save her life; the resulting scar at her throat, visible in several scenes in the film, only seemed to identify her more closely with Cleopatra. Then, in the spring of 1962, Taylor’s affair with her co-star Richard Burton became public knowledge and an international scandal. After divorcing their spouses, they married on March 15, 1964 (Burns). Taylor wore a short yellow chiffon dress designed by Irene Sharaff with a white floral headdress (fig. 41) that recalled one of her Cleopatra costumes (fig. 10).

Fig. 41 - Irene Sharaff (American, 1910-1993). Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton on their wedding day, March 15, 1964. Source: Celebuzz

Conclusion

As one of the most ambitious and expensive period films ever made, Cleopatra deserves to be seen and its production design studied. Most of the film’s multi-million-dollar budget is visible on the screen. Today’s audiences, accustomed to computer-generated-imagery, might appreciate the fact that in Cleopatra everything before the camera was real. It was nominated for nine Academy Awards and won four, including for Best Art Direction, and the three costume designers shared the award for Best Costume Design for a color film (IMDB). The Cleopatra costumes that have been preserved, such as the Phoenix cape and the “evening coat” from Elizabeth Taylor’s personal collection, have sold for high prices at auction. For example, the “Phoenix” cape sold for $59,375 at Heritage Auctions in Dallas, March 30, 2012 (Art Daily). While students of costume history should approach the film with caution, students of costume design should see Cleopatra, because of the creativity and artistry the costumes represent and the prominence of their role in the film.

References:

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment. Expanded ed. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/979316852.

- Brown, Chip. “The Search for Cleopatra.” National Geographic Magazine, July 2011. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/print/2011/07/cleopatra/brown-text.

- Brown, Susan, ed. Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. New York: DK Publishing, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/840417029.

- Burns, Kevin, and Brent Zanky. Cleopatra: The Film That Changed Hollywood. Documentary. Prometheus Entertainment, 2001.

- “Cleopatra.” IMDB. Accessed August 28, 2017. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0056937.

- “Cleopatra – Ancient History.” History. Accessed August 28, 2017. http://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/cleopatra.

- Curtis, Charlotte. “Effect of ‘Cleopatra,’ ‘Marienbad,’ Other Films Is Cited.” The New York Times, July 13, 1962. https://nyti.ms/2wckQDN.

- “Elizabeth Taylor’s Gold Cleopatra Cape Brings $59,375 at Heritage Auctions in Dallas.” Art Daily. Accessed August 28, 2017. http://artdaily.com/news/54488/Elizabeth-Taylor-s-gold-Cleopatra-cape-brings–59-375-at-Heritage-Auctions-in-Dallas-#.WaRP-oqQzfY.

- LaVine, W. Robert, and Allen Florio. In a Glamorous Fashion: The Fabulous Years of Hollywood Costume Design. New York: Scribner, 1980. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/803077041.

- Maeder, Edward, ed. Hollywood and History: Costume Design in Film. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/887804446.

- Susman, Gary. “The 19 Biggest Box Office Bombs in Movie History.” Moviefone. Accessed August 28, 2017. https://www.moviefone.com/2015/04/14/biggest-box-office-bombs-movie-history.