This color-blocked 1973 chiffon evening dress represents American designer Stephen Burrows’ original contributions to fashion as well as to the ground-breaking Battle of Versailles.

About the Look

This 1973 Stephen Burrows look (Figs. 1-2) is emblematic of Burrows’ most innovative contributions to fashion.

Although both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology call this look an evening dress, it is composed of a skirt and tunic top with a belt sash. Therefore, it may also be referred to as an ensemble.

The fabric is polyester chiffon in “multicolored hot pastels” (Esterhazy). The one-shouldered tunic is blue with an orange sash tied around the waist. The tiered skirt layers are yellow, pink and black. The blue and black fabric hems are stitched in red thread, one of Burrows’ design signatures.

On Stephen Burrows’ 1970s designs, fashion historian Sara Jablon-Roberts wrote:

“His sinuous color-blocked and lettuce-hemmed dresses were ubiquitous on young, fashionable women at the era’s dance clubs.”

This ensemble is a prime example of what Jablon-Roberts describes. The flowing tiers are in vivid colors, demonstrating the modern color-blocking technique for which he is credited. Also present is Burrows’ lettuce edge technique on the hems, which is said to be his own invention. The effect is achieved by over-stretching and over-stitching the fabric. These are also signature features of Burrows’ 1970s designs.

Contemporary press coverage of the collection included the following passage, describing Burrows’ design themes and this ensemble:

“One of his past accomplishments was to put together a number of different colors … Layering chiffon is a present occupation. He does flippy little tops over long-layered skirts that are among the few evening dresses of the season that don’t have an old-lady look. Sensitive fashion show viewers had been threatening to scream if they saw one more one-shoulder evening dress. Burrows does one that is different. Its colors are bright blue, gold, pink and black and it’s one of those layered chiffons.” (Morris 1973)

Fig. 1 - Stephen Burrows (American, b. 1943). Evening dress, ca. 1973. Polyester chiffon. New York: The Museum at FIT, 99.15.1. Gift of Mrs. Savanna Clark. Source: The Museum at FIT

Fig. 2 - Stephen Burrows (American, b. 1943). Evening dress, ca. 1973. Polyester chiffon. New York: The Museum at FIT, 99.15.1. Gift of Mrs. Savanna Clark. Source: The Museum at FIT

Stephen Burrows (American, born 1943). Evening dress/ensemble, November 1973. Polyester chiffon. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985.379.4a, b. Gift of Mrs. Anne Markley Spivak, 1985. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

About the context

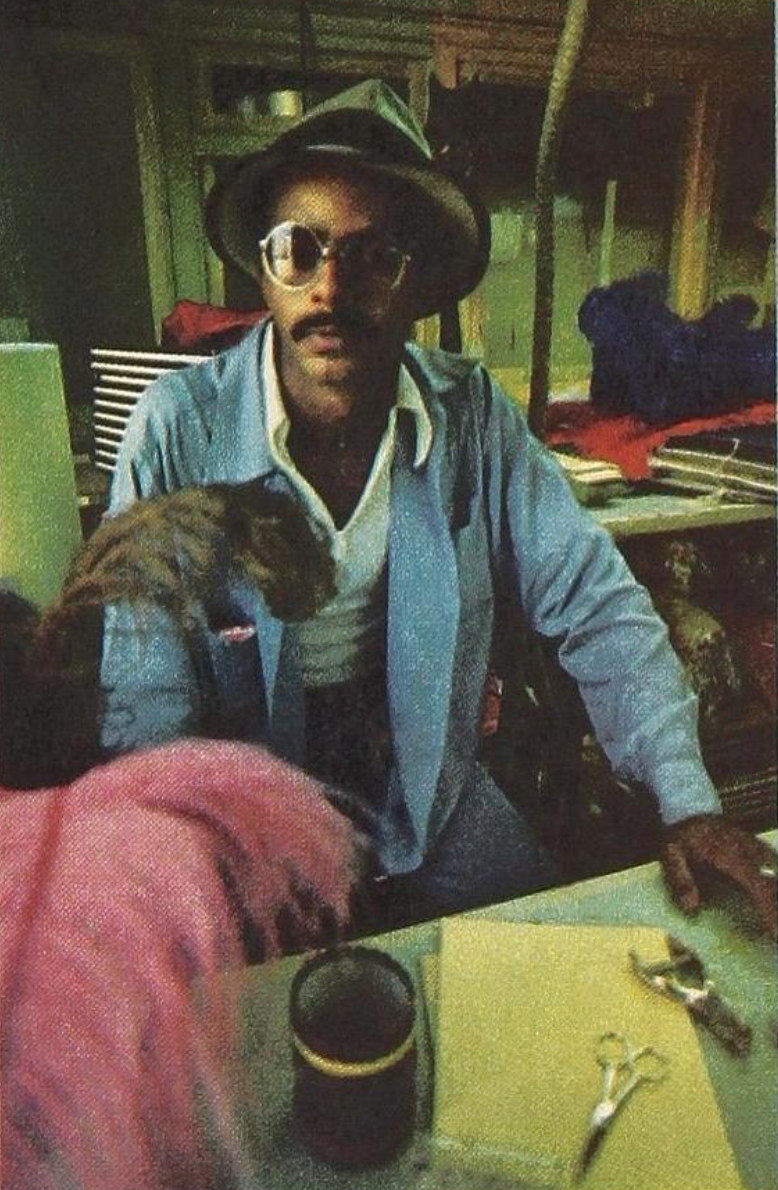

Born in Newark, New Jersey in 1943, Stephen Burrows’ (Fig. 3) interest in fashion design was encouraged by his grandmother (Jablon-Roberts). He learned from watching her sew, and is said to have sewed his first dress at nine years old (Morris 1970). Burrows obtained a degree in Fashion Design from the Fashion Institute of Technology in 1966. He then went on to design, sew, and sell dresses to friends and boutiques in New York City — including “O” Boutique, run by Burrows and former classmate Roz Rubenstein (Borden).

In some ways, Burrows’ early designs are in line with fashions of the late 1960s due to their youthful, fantastic, individualistic, and hippie themes. However, even then, Burrows’ designs ushered in the aesthetics of the ensuing decade. In 1969, the year of the “micro-mini,” Burrows favored longer skirts (Steele 82; “The Sportswear & Leisure Living: The Real Story of ‘O’.”). He also reportedly favored leather, fringe, and unisex separates (“The Sportswear & Leisure Living: The Real Story of ‘O’.”)

In 1970, “O” Boutique closed and Burrows began to work for the luxury retailer Henri Bendel (Jablon-Roberts). Bendel’s gave Burrows his own in-store boutique named Stephen Burrows’ World, where his vivid designs flourished (Morris 1970). He was praised as being an innovative and creative designer, especially when it came to his mixing-up of vibrant colors “like an abstract painter” (see Fig. 4) (Morris 1977; Morris 1973). His designs were so successful that Bendel’s even distributed them to other retailers (Jablon-Roberts).

Burrows was nominated for the Coty American Fashion Critics’ Award for design excellence in 1971 and 1972, and won in June of 1973 (“The Winners”). He was the Coty award’s first African American recipient (Jablon-Roberts).

Fig. 3 - Photographer unknown. Essence Designer Of The Month: Stephen Burrows, September 1972. Essence Magazine. Source: Essence

Fig. 4 - Stephen Burrows (American, b. 1943). Dress, Fall 1970. Wool. New York: Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, 92.105.8. Gift of Stephen Burrows. Source: Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology

Fig. 5 - Maning Obregon (Filipino American, 1939-1989). Illustration of Burrows' evening dress, November 1973. New York Times. Source: New York Times

However, that was not the only moment that made 1973 an outstanding, pivotal year in Burrows’ career. That November he released his first collection for Stephen Burrows, Inc. (which this dress belongs to), and showed it alongside Halston and his pale ultrasuedes (Morris 1973). Women’s Wear Daily felt that the collection was representative of a more serious and refined Burrows, reporting:

“His attention to cut and his tamed-down colorings reflect Stephen’s more subdued mood. The collection is filled with those great bodydresses Stephen does so well and this season there’s lots of emphasis on evening — from the slinky matte jerseys to the soft, tiered chiffons.” (“New York: Toned-Down Burrows And Ultra Halston”)

The New York Times had very high praise for the collection, writing “… it was clear that American fashion had at last produced a genius” (Morris 1973). They also covered the “tiered chiffons,” in greater detail and released an illustration (Fig. 5) of the ensemble, describing its colors as “bright blue, gold, pink and black” (Morris 1973).

Later that very same month, Burrows showed the collection at the most celebrated event of his career: the Battle of Versailles. Officially called the Grand Divertissement à Versailles (Fig. 6), the fashion show was a fundraiser to help restore the historic Palace of Versailles. Funds were raised through ticket sales to watch five French and five American designers show their collections in a spectacular performance alongside musical entertainment.

The event was organized by fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert (Fig. 7), who was often referred to as the “Empress of Fashion” (Nemy). Lambert believed that American designers were overlooked, and disagreed that Paris should remain the world’s only fashion capital. She was dedicated to promoting American fashion, and is credited with “recognizing future stars: Halston was one of them” (Nemy). The Battle of Versailles is considered a “highlight of her career” (Nemy).

Lambert chose to invite Yves Saint Laurent, Marc Bohan for Dior, Hubert de Givenchy, Pierre Cardin, and Emanuel Ungaro to represent the French. Lambert worked with them in deciding which American designers to invite (Jablon-Roberts). They decided on Halston, Oscar de la Renta, Bill Blass, Anne Klein, and Stephen Burrows. Burrows differed from the other American designers in many ways. He was the only African-American designer, and also the youngest by many years. He certainly didn’t have the level of fame or reputation that the other four designers shared. However, Burrows generated buzz and excitement as a great emerging talent.

Fig. 6 - Photographer unknown. Grand Divertissement à Versailles Program, November 1973. Los Angeles: FIDM Museum Special Collections. Source: FIDM Museum Blog

Fig. 7 - Associated Press. Eleanor Lambert, 1963. Source: MFIT

Fig. 8 - Photographer unknown. Models wearing Stephen Burrows at The Battle of Versailles, November 1973. Source: Dazed

Fig. 9 - Charles Tracy (American). Models wearing Stephen Burrows at The Battle of Versailles, November 1973. Source: Harper's Bazaar

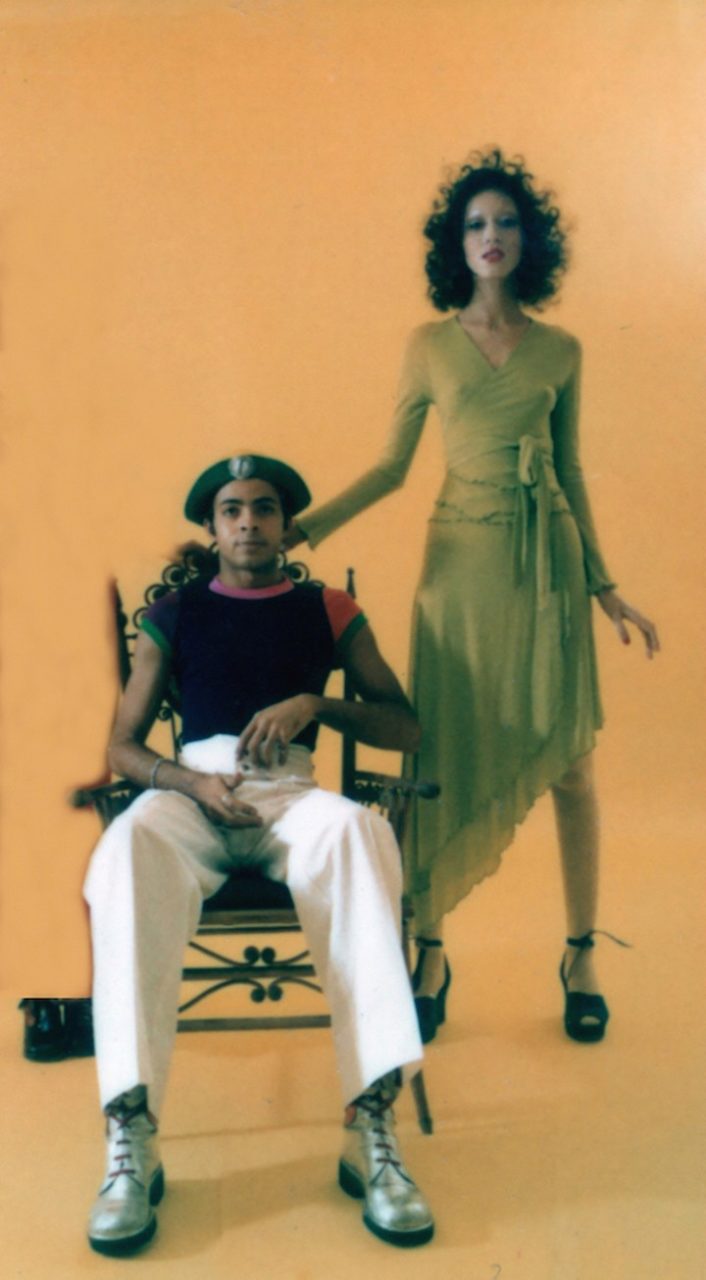

Fig. 10 - Photographer unknown. Stephen Burrows and Pat Cleveland, 1970. Source: i-D

On November 28, 1973, Lambert’s vision was realized: even the French admitted they lost the Battle of Versailles. Their segment was too formal, haughty, and over-produced. It also went on for much too long: about two and a half hours. In a stark contrast, the American show was a colorful, energetic thirty-five minutes. Figures 8 and 9 depict Burrows’ segment of the night.

The New York Times reported:

“The French show was held first, but from the moment Liza Minnelli strode onstage, belting ‘Bonjour Paris,’ accompanied by models in a symphony of vanilla to brown tones, the blue and gold theater resounded with bravos and sustained applause.” (Nemy)

A great deal of the American’s success at the Battle of Versailles is attributed to the performance of the African-American models on the runway. Not only did they add a noticeable diversity that the French lacked, but they brought with them the spirit of the Ebony Fashion Fair. Pat Cleveland, Stephen Burrows’ muse and model at Versailles, started modeling for Ebony Fashion Fair as a teenager (see Fig. 10) (Trebay).

Tied to Ebony magazine, Ebony Fashion Fair was an annual traveling fashion show founded in 1958. The show brought both renowned haute couture and lesser-known designers to middle-class African American audiences nation-wide (Nodjimbadem). It sought to represent Black women in an industry which historically excluded them. They encouraged models to walk with pride and celebrate their individualism.

Although the American designers partially owe their win to their models’ stage presence and talent, the Battle of Versailles itself is considered “a critical turning point for models of color” (Marra-Alvarez).

While the Americans won the day, it was Stephen Burrows’ part that truly stole the show. The audience’s reaction was supposedly so loud and cacophonous that Burrows worried something had gone wrong. Quite the opposite — the French adored Burrows’ colorful and original designs. Yves Saint Laurent told Women’s Wear Daily that “Stephen Burrows has great talent” (“Versailles: Americans Came, they Sewed, they Conquered.”). Burrows has said that receiving Saint Laurent’s praise was the highlight of the entire trip.

Its Afterlife

T

his ensemble is in several museum collections, including the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology and the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 2013, the ensemble was exhibited by the Museum of the City of New York in their exhibition titled Stephen Burrows: When Fashion Danced (Fig. 11). The exhibition utilized garments, photographs, and works on paper to explore Burrows’ design evolution and inspirations throughout the 1970s. According to the museum,

“Stephen Burrows: When Fashion Danced looks at the period spanning the 1970s when Stephen Burrows’s meteoric rise to fame made him not only the first African-American designer to gain international stature, but a celebrated fashion innovator whose work helped define the look of a generation. With vibrant colors, metallic fabrics, and slinky silhouettes that clung to the body, Burrows’s danceable designs generated a vibrant look that was of a piece with the glamorous, liberated nightlife of the era.” (“Stephen Burrows: When Fashion Danced”)

It was also exhibited in 2016-2017 by the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology in their exhibition Black Fashion Designers (Fig. 12). The show sought to contextualize Burrows’ legacy by discussing it within the context of other African American designers, including Ann Lowe, Willi Smith, and Patrick Kelly (“Black Fashion Designers”).

Burrows’ signature contributions to fashion have experienced sporadic revivals on the runway. For example, color-blocking was considered a fashion trend in 2011 (see Fig. 13) (Wasserman). Color-blocking, now defined as “the juxtaposition of dominant, solid colors to create a striking graphic effect,” was described as an accomplishment of Burrows in the 1970s (Hopkins; Morris 1973).

Fig. 11 - Museum of the City of New York. Stephen Burrows: When Fashion Danced, 2013. Source: Museum of the City of New York

Fig. 12 - The Museum at FIT. Black Fashion Designers, 2016. Source: Bloomsbury Fashion Central

Fig. 13 - Jil Sander (German, b. 1943). Color-blocked ensemble, Spring 2011 RTW. Source: Vogue

References:

- “Black Fashion Designers.” Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology. 2016. Accessed June 26, 2020. https://exhibitions.fitnyc.edu/black-fashion-designers/.

- Borden, Julia Bloodgood. “Burrows, Stephen.” In Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe, edited by Blanco F., José, Hunt-Hurst, Patricia, Heather Lee, and Mary Doering. ABC-CLIO, 2015. http://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2247/9781610693103

- Brady, Kathleen. “New York: Toned-Down Burrows and Ultra Halston: Stephen Burrows.” Women’s Wear Daily, Nov 09, 1973, 4-5, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1862389630?accountid=27253.

- Esterhazy, Marie-Antoinette. “The Versailles Caper: ‘One Night and Pouf–it’s Gone’.” Women’s Wear Daily, Nov 29, 1973, 1-5, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1862393866?accountid=27253.

- Hopkins, John. “Colour and Fabrics.” In Fashion Design: The Complete Guide, 76–107. London: Fairchild Books (UK), 2012. Accessed July 01, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218474.ch-003.

- Jablon-Roberts, Sara. “Stephen Burrows.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: The United States and Canada, edited by Phyllis G. Tortora. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed June 28, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781847888525.EDch031717.

- Marra-Alvarez, Melissa. “Ethnicity and the Catwalk.” In Fashion Photography Archive. London: Bloomsbury, 2015. Accessed July 01, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474260428-FPA007.

- Morris, Bernadine. “Burrows and Halston – It Was a Good Day on 7th Ave.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Nov 09, 1973. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/119763586?accountid=27253.

- Morris, Bernadine. “Fashion Saga: Cheers for a Happy Ending.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Apr 30, 1977. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/123352845?accountid=27253.

- Morris, Bernadine. “The Look of Fashions for the Seventies in Colors that can Dazzle.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Aug 12, 1970. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/117971266?accountid=27253.

- Nemy, Enid. “Eleanor Lambert, Empress of Fashion, Dies at 100.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Oct 08, 2003. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/92615018?accountid=27253.

- Nemy, Enid.”Fashion at Versailles: French were Good, Americans were Great.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Nov 30, 1973. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/119742741?accountid=27253.

- Nodjimbadem, Katie. “Reliving the Ebony Fashion Fair Off the Runway, One Couture Dress at a Time.” Smithsonian.com. April 21, 2017. Accessed July 01, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/reliving-ebony-fashion-fair-runway-one-couture-dress-time-180962987/.

- Steele, Valerie. Fifty Years of Fashion: New Look To Now. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/955193317.

- Stephen Burrows: When Fashion Danced.” Museum of the City of New York. 2013. https://www.mcny.org/exhibition/stephen-burrows.

- “The Sportswear & Leisure Living: The Real Story of ‘O’.” Women’s Wear Daily, Apr 03, 1969, 26, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1523505710?accountid=27253.

- “The Winners.” Women’s Wear Daily, Jun 22, 1973, 1, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1627611991?accountid=27253.

- Trebay, Guy. “She’s Still Got that Strut: In a New Memoir, Pat Cleveland, One of the First Black Supermodels, Looks Back on a Life Brimming with Glamour and Challenges.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Jun 16, 2016. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2310036231?accountid=27253.

- “Versailles: Americans Came, they Sewed, they Conquered.” Women’s Wear Daily, Nov 30, 1973, 1, 6, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1862394596?accountid=27253.

- Wasserman, Sydney. “It’s All About: Block Party.” ELLE. April 22, 2011. Accessed July 01, 2020. https://www.elle.com/fashion/g2508/its-all-about-block-party-561532/?slide=9.