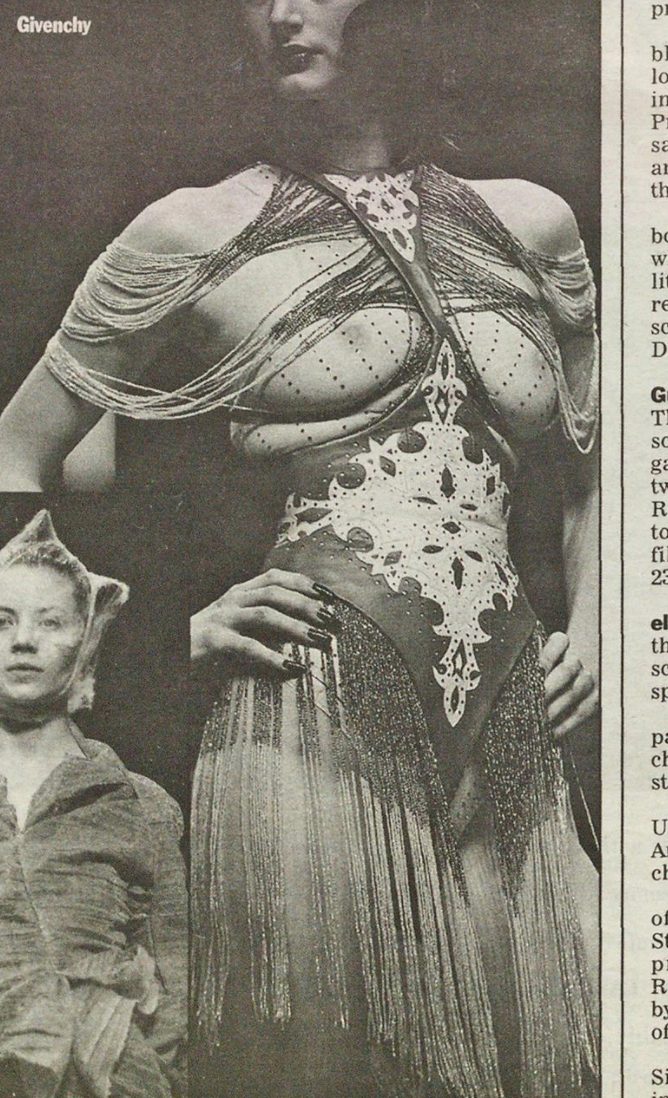

Galliano’s stringy suede shimmy dress from the 1996 F/W Baby Maker collection captured the originality and innovative qualities of his work – but also the appropriation of Native American cultures that he indulged in at this time.

About the Look

John Galliano was inspired by Native American culture for his Fall/Winter 1996-97 collection and appropriated aspects of Native American fashion for his palette, material, and patterns. The tan suede used channels the look of Native American deerskin suede garments, particularly those of Plains tribes like the Blackfoot (Niitsitapi (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ)).

The attention to detail is impeccable. Each pattern was laser-cut to create precise lines, and a flowing structure and exciting textures. The strings of suede hang in a way that encourages the eye to move up and down the body. The garment hangs on the body and yet is designed in such a way that it carefully reveals curves in a manner more akin to 1930s bias-cut evening gowns than Blackfoot dress. Each piece moves with the model as she walks down the runway. The techniques used to produce this dress were innovative in the late nineties, and the collection itself was considered to be edgy and unexpected, though appropriation of Native styles had been common since at least the 1970s.

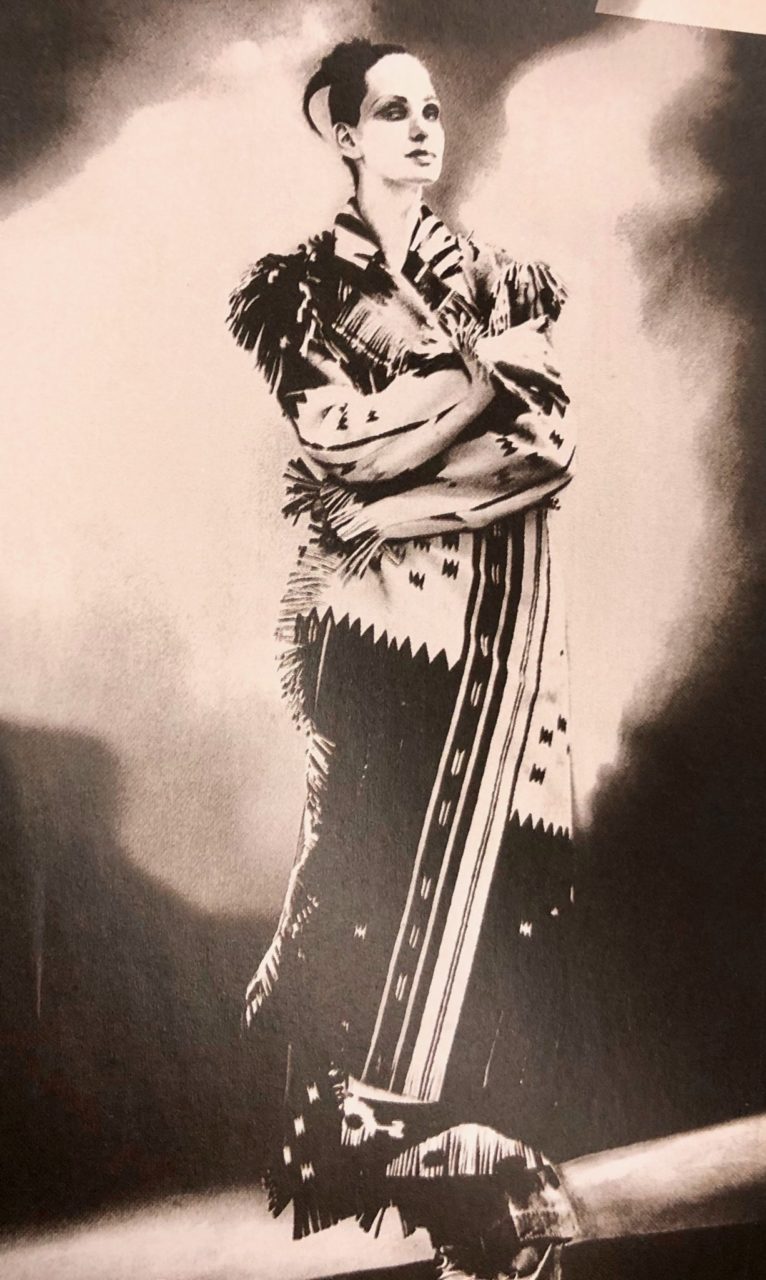

Fig. 1 - John Galliano (British, 1960-present). Dress, Fall/Winter 1996-97. Leather. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.46. Gift of John Galliano S.A., 2004. Source: MMA

John Galliano (British, 1960-present). Dress, Fall/Winter 1996-97. Leather. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.26. Gift of John Galliano S. A., 2004. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

About the context

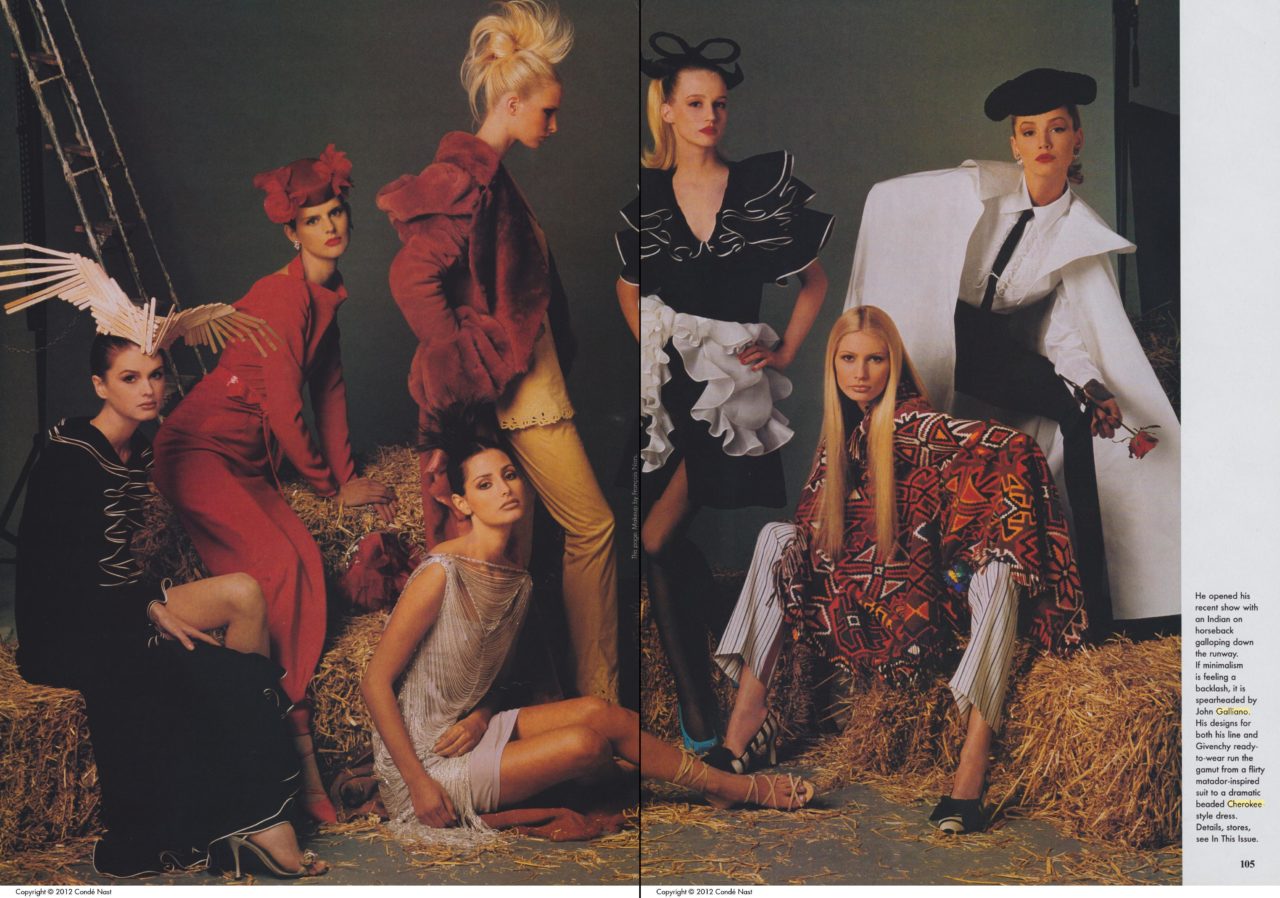

For his 1996-97 Fall/Winter collection, Galliano drew inspiration from multiple Native American cultures in a clear example of cultural appropriation. He set the scene with objects featuring what he considered to be classic Native American patterns; see figure 2 for a cocoon coat with motifs taken from traditional Navajo (Diné) iconography (Fig. 3). Some of the coats (Fig. 4) combined the Navajo blanket look with a kimono cut and Indonesian ikat patterning. The runway was set up with seemingly discarded items – toppled oil barrels, bits of old car, and various symbols of the American West, as if to conceptualize a dirty, forgotten land of the past rather than an area where many Native Americans still live and work today.

Fig. 2 - John Galliano (British, 1960-present). Cocoon Coat, 1996-97. March 1996. Source: Harper's Bazaar

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (Diné (Navajo)). Shoulder blanket, 1890s. Hand-spun wool. Washington, DC: National Museum of Natural History, 160986. Source: NMNH

Fig. 4 - John Galliano (British, 1960-present). Coat, Fall/Winter 1996-97. Wool felt, silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.410. Source: MMA

Galliano’s Fall/Winter 1996-97 collection for his own label was titled Baby Maker. Mimi Avins of the Los Angeles Times called it “a jumble of mixed metaphors” in her “Fall Collections” review (np). In Galliano: Spectacular Fashion (2020), Kerry Taylor describes its convoluted setup:

“Galliano’s collection had two heroines: soignée Wallis Simpson, wife of abdicated King Edward VIII, and Pocahontas, the ‘Cherokee babe’ whom he described as ‘a proper little [pejorative slur] on her podium straigtening her seams’…In their narrative, Wallis attends a Hopi/Cherokee wedding in the middle of the desert…” (122)

Pocahontas, born Matoaka and known as Amonute, was neither Hopi nor Cherokee but in fact Powhatan. The Hopi inhabit lands in Arizona in the south-west; the Cherokee North Carolina in the south-east; and the Powhatan Virginia in the mid-Atlantic United States. Galliano pulled together several very different cultures and time periods in order to set his show. He also brought together a privileged white woman connected with a historical colonial power–Great Britain–and a woman who was forced to assimilate by that same power.

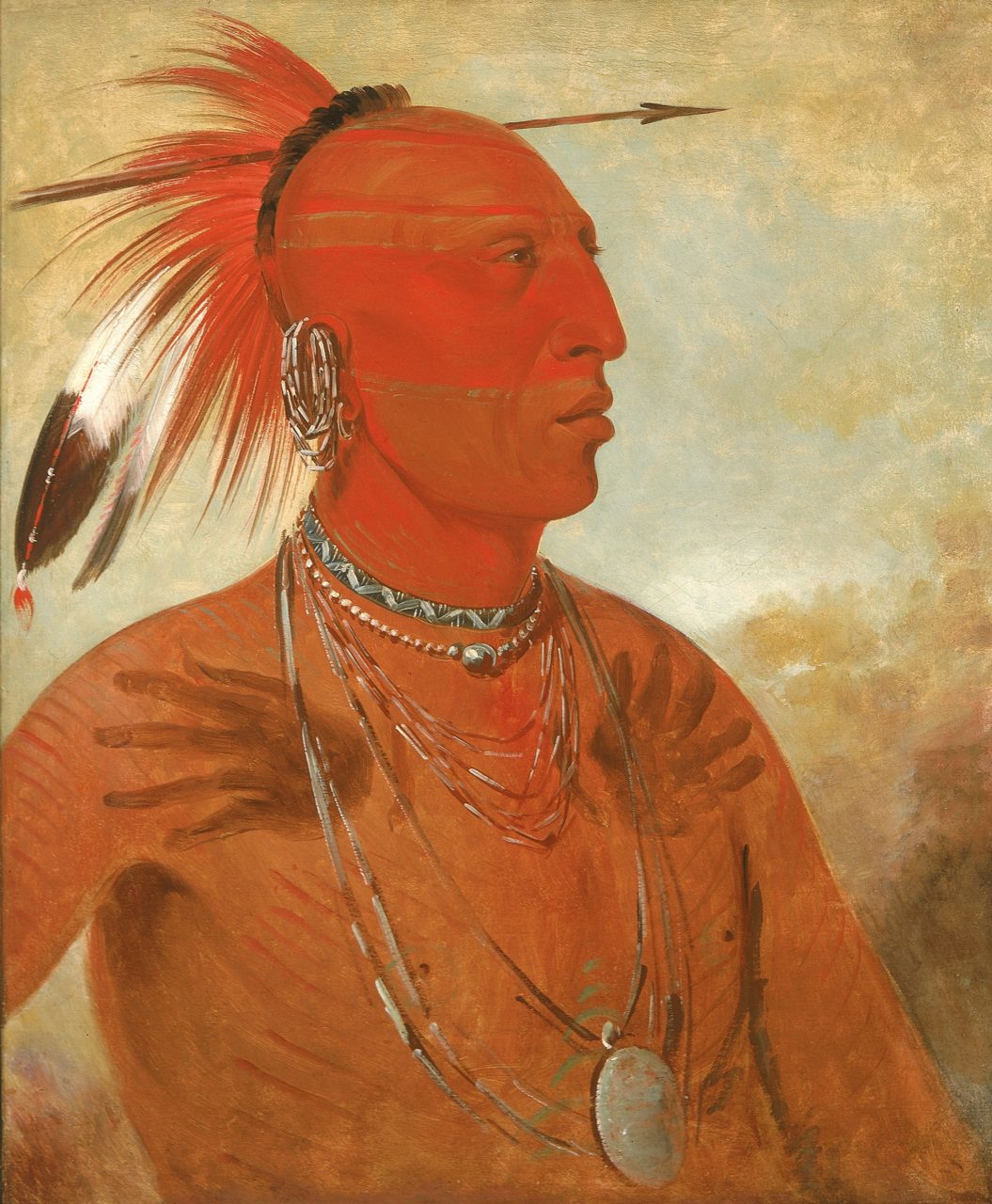

Fig. 5 - John Galliano (British, 1960-present). Mohawk look from the runway, Fall/Winter 1996-97. Paris: Fashion Channel, 4:37. Source: YouTube

Fig. 6 - George Catlin (American, 1796-1872). La-wáh-he-coots-la-sháw-no, Brave Chief, a Skidi (Wolf) Pawnee, 1832. Oil on canvas; 73.7 x 60.9 cm (29 x 24 in). Washington, DC: Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1985.66.110. Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr.. Source: SAMM

The show began with a man riding a frantic horse alongside the runway. Models strutted down the catwalk with their hair styled in mohawks (Fig. 5) (a misnomer; often attributed to the north-eastern Mohawks (Kanienʼkehá꞉ka), the style more closely resembles that of the Pawnee people (Chatiks si chatiks) of the midwest (Fig. 6)). Their faces were painted with random designs in an approximation of traditional war paint, in which each line, each color, has meaning, and it is “not so much about war as it is about ceremony” (Hopkins). Native cultures can have different meanings for shared designs, and Galliano’s versions are basically gibberish on non-Native faces.

Though the show is Native American inspired, Galliano failed to feature any Native American women on the runway. He used mostly white models with darker makeup and ‘war paint’ and combined disparate cultures with very different traditions into one contextless show. The thoughtfulness put into construction of the garments and the artistic presentation of the show did not carry over into his research or representation. If this show had been planned today, Galliano would be mired in controversy rather than lauded.

Fig. 7 - John Galliano (British, 1960-present). Vogue's View: Runway '96, 1996. Vogue, Vol. 186, Iss. 7, (Jul 1, 1996): 54. Photo by Roxanne Lowit. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (Niitsitapii (Blackfoot)). Woman's dress, Before 1921. Hide, cowrie shell/shells, glass bead/beads, hide thong/babiche. Washington, DC: National Museum of the American Indian, 10/7445. Source: NMAI

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (British). Evening dress, ca. 1932. Light green satin. Charleston Museum. Source: Flickr

Though the inspirations and runway presentation had serious flaws, many of the garments were more than simple copies of traditional Native dress. Galliano created what Women’s Wear Daily referred to as “suede string shimmy dresses” (Fig. 7). Inspired by deerskin suede garments worn by Plains Natives like the Blackfoot (Fig. 8), Galliano laser-cut the fabric into strips and patterns in order to create these detailed looks. Many of the final gowns have 1930s evening cuts; fishtail skirts, godets, and clear diagonal lines for dresses that appear slinky and glamorous (Fig. 9).

Colin McDowell wrote in Galliano (1998) that the designer regarded the collection as pivotal:

“If you view it on its own, you can see the cut, the techniques, the clash of fabrics. I love the print of the coat, and look at the dress-all the cuts. There was nothing like this at the time! Fashion really should capture the moment in textures and styles…” (np)

People were awed by the Galliano line; a March 15th, 1996 Women’s Wear Daily article titled “Two Shining Moments” claimed:

“The truth of the matter is that this was Galliano at his Galliano best – and there wasn’t a whiff of anti-fashion for miles…This collection was elaborate, rich, imaginative and romantic in the way we sometimes forget gashion should be – at least on occasion. And that was precisely Galliano’s goal.” (11)

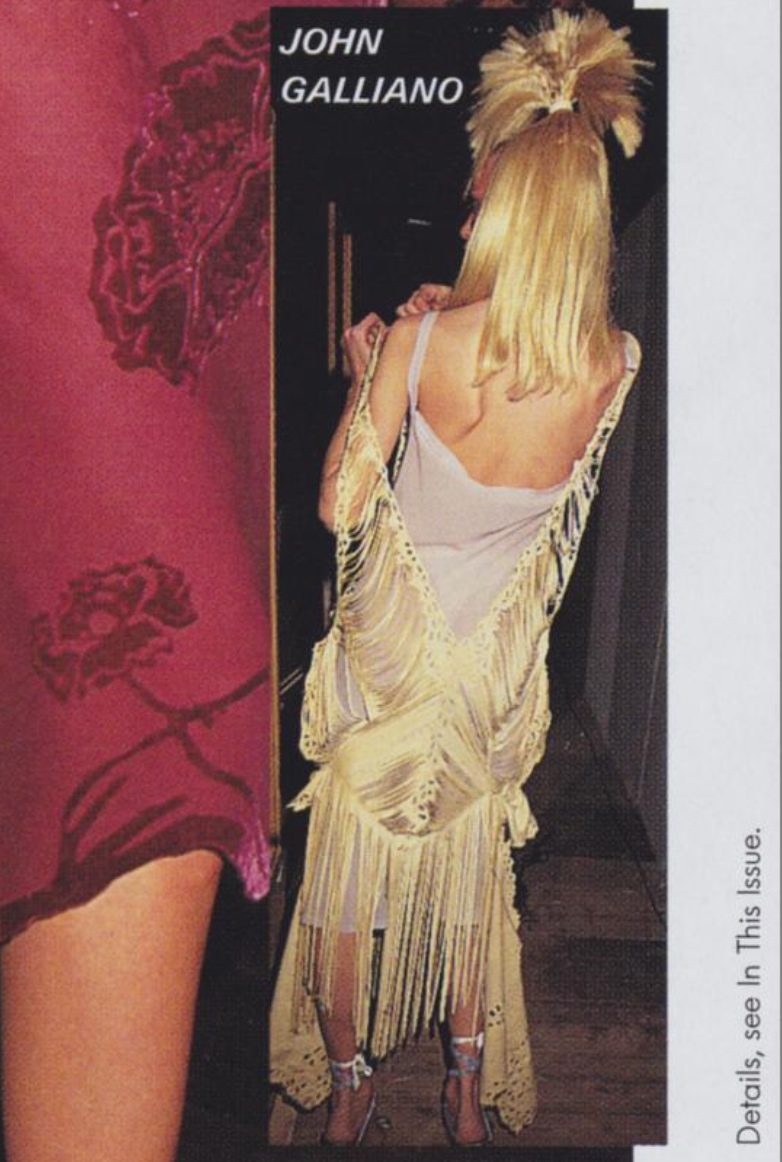

The dramatics of the presentation alongside technical prowess and exoticized cultures had the fashion world impressed. It seemed a “tribute to the American Indian”…but the set was also a “burial ground” (11). Editorial shoots done with the garments after the show left out many of the more aggressive aspects of Galliano’s presentation (Fig. 10), and focused on details like the movement of fringe (Fig. 11).

Galliano’s collections were always unexpected, exciting, and outrageous. This reputation led his role as the head designer at Givenchy in 1995 and Christian Dior in 1996. In The History of Modern Fashion from 1850 (2015), Daniel James Cole and Nancy Diehl explain: “His designs combined historical references with impressive craftsmanship and re-established the allure of Dior” (396).

In Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: Image and Morality in the 20th Century (2001), Rebecca Arnold describes fashion in the 1990s:

“The revival of couture during the middle of the decade increased the sense of decadence fed by the extravagant designs of Galliano for Dior…The lure of luxury fabrics and the relish taken in extravagant decoration, may be seen as vulgar…but it should perhaps be remembered that fashion’s ‘blatant consumerism shocks the culture whose heart it yet speaks so well.'” (10)

Fig. 10 - John Galliano for Galliano and Givenchy (British, 1960-present). Fashion's New Establishment, Fall/Winter 1996-97. Vogue, Vol. 186, Iss. 7 (Jul 1, 1996): 104-5. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 11 - Craig McDean (British, 1964-present). Kate Moss in John Galliano, 1996. Photograph. Vogue UK. Source: Condé Nast

Fig. 12 - John Galliano for Givenchy (British, 1960-present). The Year In Fashion: January, 1996. Women's Wear Daily, Vol. 174, Iss. 113 (Dec 15, 1997). Source: ProQuest

Shortly after Baby Maker debuted, Givenchy released a theatrical dress with a similarly stringy effect (Fig. 12), and Galliano went on to design more Native American-inspired clothing for a Dior show, Les Incroyables, the next year. Galliano had the privilege of a situation in which he could take risks, but such a collection would not be appropriate today.

Its Afterlife

There has also been a movement to recognize Native fashion designers in their own right, like Tammy Beauvais (Mohawk), Curtis Oland (Lil’Wat) (Fig. 13), and Bethany Yellowtail (Crow/Northern Cheyenne) (Fig. 14).

Fig. 13 - Curtis Oland (Lil’Wat-Canadian, Active 2016-present). Horse Medicine, Autumn/Winter 2019. Cotton canvas, horsehair fringe, viscose, copper, cotton muslin. Delicate Tissue. Photo by Theresa Marx. Source: Curtis Oland

Fig. 14 - Bethany Yellowtail (American (Crow and Northern Cheyenne), Active 2009-present). An Interview with Alter-NATIVE’s Bethany Yellowtail, ca. 2017. Source: Design Sponge

References:

- Arnold, Rebecca. Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: Image and Morality in the 20th Century. London: Tauris, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1154963520

- Avins, Mimi. “The Fall Collections / Paris: Au Revoir to Those Simpler Times.” The Los Angeles Times, March 18, 1996. Accessed 7 June 2020. www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-03-18-ls-48395-story.html

- Betts, Katherine. “Vogue’s View: Runway ’96.” Vogue 186, no. 7 (Jul 01, 1996): 39-54. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879294669?accountid=27253

- Cole, Daniel James, and Deihl, Nancy. The History of Modern Fashion from 1850. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/946909490

- Hopkins, Ruth. “The Use of War Paint in Native Communities is Evolving.” Teen Vogue, April 10, 2020. Accessed 7 June 2020. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/use-war-paint-native-communities

- Lehnert, Gertrud. A History of Fashion in the 20th Century. Cologne, Germany: Konemann, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/605898065

- McDowell, Colin. Galliano. New York: Rizzoli, 1998. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/929880160

- “Two Shining Moments.” Women’s Wear Daily, Mar 15, 1996, 1-13. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1445741385?accountid=27253