Renaissance beauty was not skin deep. In order to be considered beautiful (and fashionable), an early modern woman must also be virtuous.

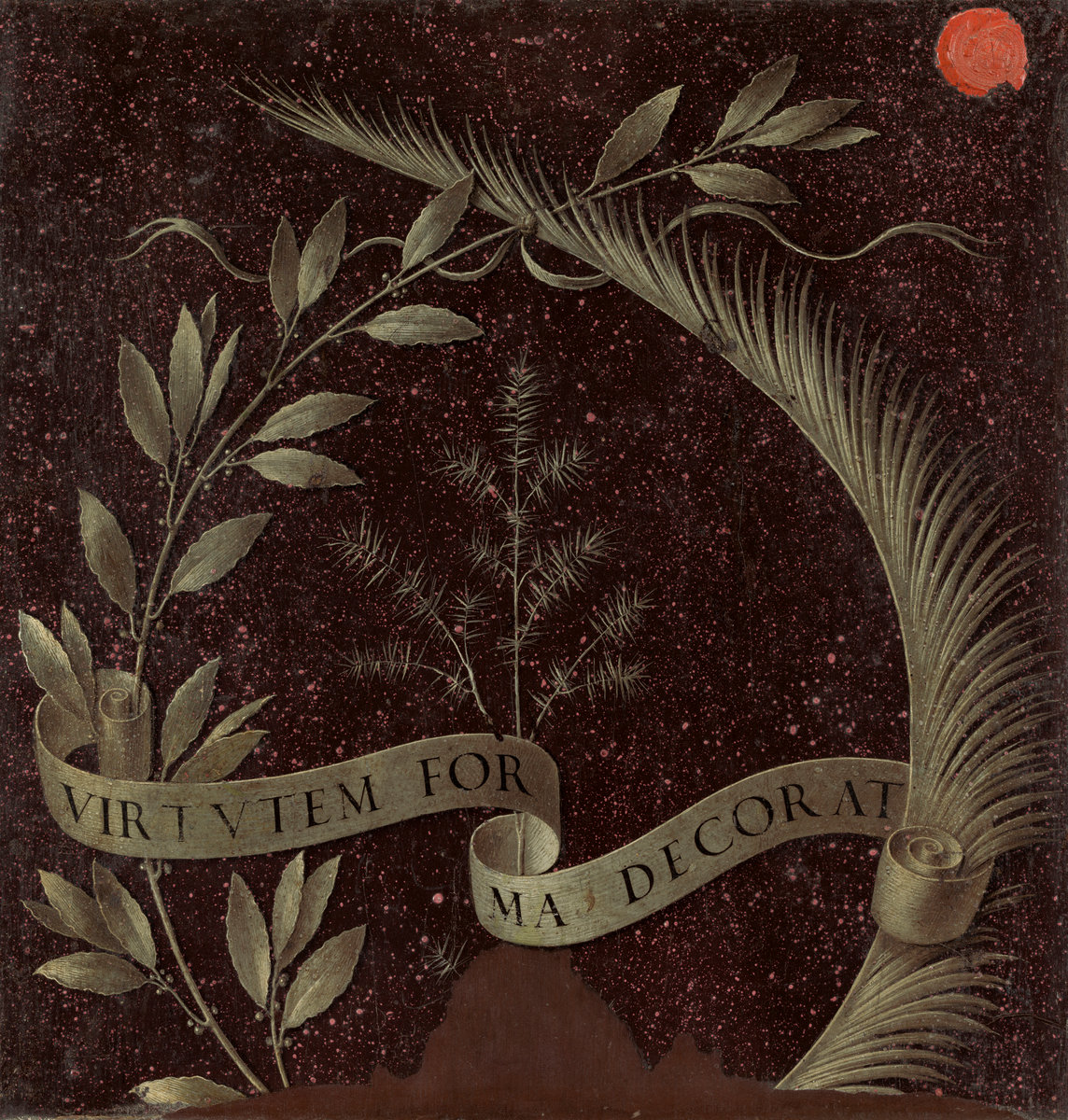

Around 1474-8 Leonardo da Vinci painted his iconic portrait of the Florentine noblewoman Ginevra de’Benci (Fig. 1a). The front panel displays the aristocrat’s face, while the back uses flora to represent her personality. The two sides blend together, creating a full picture of Ginevra de’Benci. The sitter wears a brown kirtle laced with blue ribbon, and a halo of tight ringlets surrounds her face. The obverse side of the portrait (Fig. 1b) proclaims Ginevra’s literary intellect with a laurel leaf, which intersects with a palm frond (a typical attribute carried by martyred saints) to suggest her strong moral character. Both symbolic branches encircle a sprig of juniper, a pun on the sitter’s given name. A banner of trompe-l’oeil paper intertwines all three plants, displaying a Latin motto: “VIRTVTEM FORMA DECORAT,” or “Beauty adorns virtue (Brown, 64).” Ginevra de’Benci is unique within Renaissance female portraiture due to its focus on the sitter’s individuality. However, the painted words “Beauty adorns virtue” reverberate across nearly all portraits of women from the period. Renaissance women were expected to use lavish clothing, jewelry, accessories, and cosmetics to adhere to contemporary beauty standards. However, Renaissance beauty was not skin deep. In order to be considered beautiful (and fashionable), an early modern woman must also be virtuous.

Fig. 1 - Leonardo da Vinci (Florentine, 1452-1519). Ginevra de' Benci, ca. 1474/1478. Oil on panel; 38.1 x 37 cm (15 x 14 9/16 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1967.6.1.a. Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund. Source: NGA

Fig. 1 - Leonardo da Vinci (Florentine, 1452-1519). Wreath of Laurel, Palm, and Juniper with a Scroll inscribed Virtutem Forma Decorat, ca. 1474/1478. Washington: NGA. Source: NGA

During the Renaissance, creating textiles was extremely expensive and time-consuming, so clothing was often recycled. If a dress was torn, stained, or became too small for its wearer, it would be cut, re-stitched, and reused as a seat cushion cover, for example, or clothing for children. Further, fabric decays quickly relative to other materials. As a result, there are very few full ensembles surviving from the Renaissance. Because pieces of clothing (and complete outfits) are so scarce, we must instead rely on pictorial media to understand what Renaissance peoples considered fashionable. While paintings are not always perfect mirrors of the past, they give us the best available estimation. Italy was a fashion forerunner at the time, and as such Italian portraiture helps us understand what people wore in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Men’s dress

Fashion trends in this period were generally set by the aristocracy and upper-classes. A patrician closet relied on a vast network of tailors, dressmakers, purse-makers, metalsmiths, furriers, embroiderers, lace-makers, and leather-workers to stay abreast of the latest trends. Courts would often employ private fashion designers to clothe the royal family. A wall fresco of Ludovico Gonzaga and his Family and Court (Fig. 2) painted by Andrea Mantegna between 1465-74 elucidates what men wore in fifteenth-century Italian courtly circles. Men’s clothing in this period enjoyed a wide range of colors. The courtiers wear red, blue, gold, pink, or green belted tunics. They all sport red circle-brimmed caps. Men’s hemlines in the fifteenth century ended above the knee to show off two-tone hose. As the period advanced, men’s hemlines ascended higher and higher up stockinged legs, ultimately culminating in the need for the codpiece in the mid-to-late sixteenth century.

Fig. 2 - Andrea Mantegna (Italian, 1431-1506). The Court of Gonzaga, ca. 1465-1474. Walnut oil on plaster; 805 x 807 cm (316.9 x 317.7 in). Mantua: Ducal Palace. Source: Wikimedia

This scene also gives insight into the ways clothing signaled authority and social connection in the fifteenth century. The men in the image all wear one white and one reddish stocking because this marks them as servants or household members of Ludovico Gonzaga’s (sitting on the far-right side of the fresco, wearing an off-red robe) Mantuan court. The ruler has marked his courtiers with his house colors. This helped visually identify men who had sworn fealty to Mantua, and promoted tonal unity in public settings. Clothes were also often used as payment for services rendered. Clothing, therefore, was a central facet of both politics and economic stability.

In the sixteenth century, men’s fashions turned towards darker, more somber hues in their fabrics. Baldassare Castiglione, writer of a popular book on etiquette, The Courtier (published 1528), tells upper-class men how to dress. Castiglione insists he:

“…would like our courtier always to appear neat and refined and to observe a certain modest elegance, though he should avoid being effeminate or foppish in his attire and not exaggerate one feature more than another.” (164)

Sixteenth-century men dressed down to display seriousness and sobriety. Men’s tunics, jackets, and stockings were generally tailored from black or dark brown luxury fabrics like velvet or silk. Women’s clothing, however, offered more complexity and variety throughout the Renaissance.

Fig. 3 - Fra Filippo Lippi (Italian, 1406-1469). Portrait of a woman, 1445. Oil on poplar panel; 49.5 x 32.9 cm. Berlin: Gemäldegalerie, Ident.Nr. 1700. Source: Gemäldegalerie

Fig. 4 - Domenico Ghirlandaio (Domenico Bigordi) (Florentine, 1449-1494). Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, 1489-1490. Mixed media on panel; 77 x 49 cm. Madrid: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Inv. no. 158 (1935.6). Source: Thyssen-Bornemisza

Fifteenth-century women’s dress

Fra Filipo Lippi’s Portrait of a woman (Fig. 3), painted around 1445 is a touchstone for fifteenth-century female beauty and dress. The unknown sitter’s lips and cheeks have been lightly rouged with cosmetics to highlight her youthful glow. Her fair complexion, bright eyes, rosy lips, and blonde, expertly-coiffed hair all refer to a popular fictional late Medieval lady, Laura. Petrarch describes his muse, Laura, in his humanist poetry collection Il Canzoniere or song book. Laura is also portrayed as perfectly virtuous and chaste in Petrarch’s poems, which enhances her unearthly beauty. This book was so popular in Renaissance Italy it inflected beauty standards; thanks to Petrarch’s ladylove, early modern gentlemen preferred blondes. Even Christ’s mother, Mary, is depicted with golden hair in most period paintings. Women dyed their hair to achieve the desired tone. The Trotula, a twelfth-century text on women’s medicine, advises:

“For coloring the hair so that it is golden. Take the exterior shell of a walnut and the bark of the tree itself, and cook them in water, and with this water mix alum and oak apples, and with these mixed things you will smear the head (having first washed it) placing upon the hair leaves and tying them with strings for two days; you will be able to color [the hair]. And comb the head so that whatever adheres to the hair as excess comes off. Then place a coloring which is made from oriental crocus, dragon’s blood, and henna (whose larger part has been mixed with a decoction of brazil wood) and thus let the woman remain for three days, and on the fourth day let her be washed with hot water, and never will [this coloring] be removed easily.” (Green 115)

Notice also that the hairline in Portrait of a woman is unnatural. Fifteenth-century women often plucked or shaved their hairline back several inches, towards the illusion of a lengthy forehead, a sign of intelligence. She has severely tweezed her eyebrows to complete the effect.

The dress style in Portrait of a woman is typically fifteenth-century. Fashionable gowns positioned female waistlines above the hips, accentuated the waist with a belt or girdle, and generously poured uninterrupted volumes of fabric towards the feet (Landini and Bulgarella 90). These gowns, which are referred to in period inventories as a gonna, gonnella, sottana, gamurra, or cotta interchangeably, could be hemmed at the ankles or floor. A wealthy early modern woman wore at least three—often four—complete layers of clothing in public. On special occasions a woman would wear another gown atop the gamurra called a giornea, usually patterned and made of velvet or silk brocade. The unknown figure in Portrait of a woman wears a green gamurra, while Giovanna da Tornabuoni (Fig. 4) wears both layers in her portrait. A woman’s exterior-most gown was the most expensive and ostentatious, as it faced the evaluating world (Frick 162). An outer garment alone could require eight braccia, or a little over five yards (4.5 meters) of fabric. Beneath their sumptuous gowns, women typically wore a chemise or camicia (Fig. 5), an undershirt that pressed directly against the skin. The white fabric peeking out from under the larger, green sleeve worn by Lippi’s sitter is an example. Between the camicia and gamurra women usually wore another over-dress. An upper-class woman’s clothing was thick, voluminous, and dense.

Fig. 5 - Maker unknown (Italian). Camicia or chemise (shirt), 16th century. Linen, silk and metal thread. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 10.124.2. Rogers Fund, 1910. Source: The Met

Fig. 6 - Maker unknown (Italian). Belt or girdle with a woven love poem, 16th century. Tapestry weave band with silk and metal thread; 167.6 x 6.4 cm (66 x 2.5 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 46.156.73. Fletcher Fund, 1946. Source: The Met

While the ensemble in Portrait of a woman may seem simple at first glance, it is in fact very lavish when considered within the context of the fifteenth century. Her overgown is dyed a vibrant shade of green, as bright jewel-tones were very popular for women’s clothing during the Renaissance. Pleats begin just below the breasts and expand at her waistline. Her long sleeves are a symbol of wealth and status, as the extra fabric hinders manual labor. Her skirts bunch and spring from her waist. Neckline and sleeves are lined with a thick fabric, perhaps muslin or even fur. Small, decorative holes are bored into her belt and undershirt. A strand of identical pearls hangs from her neck. Though the sitter’s hair is covered, viewers can assume it is arranged in a complex up-do. Two types of lace make up the headdress, one porous with seamed holes. A sheer lace veil sweeps around her neck. The veil symbolizes her adherence to humility and religious norms. A closer look at the veil reveals how very expensive this accessory was: tiny pearls trim its outer edges and line the main body.

Portrait of a woman may be a marriage portrait. The sitter’s hands are dotted with six rings, which were exchanged during Renaissance engagement and wedding ceremonies. Her pinned-up hair also possibly attests to her wedded status, as young Italian women only wore their hair down to announce marital availability. Further, the pearls she wears on both her necklace and headdress may also be read as potent symbols of sexual purity. Across Western Europe, young women wore pearls to broadcast their virginity, considered the most desirable trait in marriage negotiations. Her white, stippled belt may be a further marker of chastity. Belts were closely associated with marriage, sexual virtue, and pregnancy, and were commonly given as gifts from groom to bride, such as this example in the Metropolitan Art Museum’s collection (Fig. 6), which bears a love poem stitched in precious metal. Women were expected to be unflinchingly loyal to their husbands. While men often waited until mid-life to marry (so that they had time to grow their estate or business beforehand), marriage age for Renaissance women was late adolescence or early adulthood, with the optimal ages for best childbearing potential falling between fifteen and nineteen. If an upper-class woman was fortunate enough to have her portrait made, it was likely in celebration of her engagement or wedding. Lippi’s sitter, then, is likely a teenager.

This woman is performing Renaissance decorum, from her gaze to the position of her hands. Not only is her gaze pointed outside the frame, her eyes are also half-lidded. Downcast or avert eyes were a sign of feminine modesty. Lippi’s sitter clasps one hand to her sleeve and the other lightly strokes her collar. A popular handbook for upper-class maidens, the Décor Puellarum (printed in Venice in 1469) urged young ladies:

“not to touch yourself, nor others, nor any part of the body with your hands, except when absolutely necessary. Your right hand must always rest upon your left, in front of you, on the level of your girdle.”

It was socially safer for women to touch clothing or accessories rather than allow their hands to wheel through open air, or make contact with their own bare skin. Notice also how the woman is painted obviously inside, as the public sphere was generally reserved for men. Again, the words unfurling across the banner in Ginevra de’Benci, “beauty adorns virtue” may be easily applied to this sitter.

Sixteenth-century women’s dress

Women’s clothing in the sixteenth century remained similarly structured, with several layers beneath a sumptuous principle gown. However, a wider range of textures and additional detailing became fashionable. The Palazzo Reale in Pisa owns a rare, fully-intact Italian dress (Fig. 7) from the late sixteenth century, tailored circa 1550-60. This incredible survival gives a unique glimpse into changes to women’s dress in the sixteenth century. A tight, pointed bodice laces up the sides. Tassels accentuate the bodice and would have jangled as the wearer moved, adding to the gown’s lived intensity. The slits in the sleeves show off the underwear, usually made of silk or fine cotton, yet another hint that the wearer enjoys high status. Luscious red velvet panels are lined with embroidered trim. This dress is lavish in its sheer amount of fabric. The skirting extends in a bell towards the ground, and boasts a long train, heightening the public spectacle as the wearer walked through open streets. Typical Renaissance gowns covered the wearer from waist to feet, and were so long she was forced to carry her skirts to walk unhindered. Red-dyed fabrics have a long historical pedigree of association with wealth. A hue of such high saturation required the slaying of innumerable New World cochineal insects, whose bodies were crushed for textile dyes (Monnas 157).

Fig. 7 - Maker unknown. Gown, ca. 1550-60. Pisa: Museo di Palazzo Reale. Source: Pinterest

Tightly-laced corsets entered into popular fashion in the mid-to-late sixteenth century. The introduction of the steel corset into European female undergarments is apocryphally attributed to Catherine de’Medici in 1579 (Steele 2-7). According to a popular legend, the fertile Queen consort, who was with child nine times during her marriage to Henry II of France, desired a wearable instrument to shore up the contours of her postpartum figure. However, paintings tell us body-shaping implements were introduced earlier. Notice how stiff Eleonora of Toledo’s bodice is in Bronzino’s iconic portrait of the Spanish noblewoman (Fig. 8). Expensive accessories also grew more lavish in this era. Eleonora wears a snood (a hairnet) and a bavero (shoulder covering), both made of cloth-of-gold and decorated with pearls.

Fig. 8 - Bronzino (Italian, 1503-1572). Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni de' Medici, 1544-45. Oil on panel; 115 x 96 cm (45.3 x 37.8 in). Florence: Uffizi. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 9 - Lavinia Fontana (Italian, 1552–1614). Portrait of a Noblewoman, ca. 1580. Oil on canvas; 45 1/4 x 35 1/4 in cm. Washington: National Museum of Women in the Arts. Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay. Source: NMWA

Lavinia Fontana’s Portrait of a noblewoman (1580) showcases sixteenth-century Bolognese fashion (Fig. 9). A high collar and stiff, starched ruff surround the sitter’s face. A jeweled headband crowns her head. Her dress may be a wedding dress, as burgundy was a popular color for brides. This woman is careful to respect period sumptuary laws (civil restrictions on what could and could not be worn in public); women were only allowed to wear multiple necklaces if one hosted a cross (Murphy 96).

A small dog perches on her skirt beneath her caress. This animal is yet another signal to the viewer that this woman is extremely wealthy. Upper-class women often kept little dogs as luxury pets, as they were too small for hunting and thus only useful as companions and living accessories. The dog itself wears a gemstone collar. The creature is also symbolic of marital fidelity, as the animals were considered naturally loyal. The need to preserve a woman’s chastity was still tantamount throughout sixteenth-century portraiture.

It is possible the bejeweled martin head hanging from her belt (a popular accessory for women in the period) symbolizes pregnancy or the promise of future pregnancy (Musacchio 172). The head swings directly below her womb. Martins and weasels (a Renaissance person would not have made a distinction between species) were thought to reproduce rapidly, and so this fashionable accessory may double as a quasi-magical token used to generate future progeny. Ermines were also symbols of purity.

Clothing and jewelry, however, are the true subject of Portrait of a noblewoman. Every facet of every jewel, every stitch of the gown is rendered with high accuracy. Caroline Murphy argues that the extensive detail paid to the elaborate gowns and jewels of Bolognese noblewomen by Lavinia Fontana act as painted dowry inventories (Murphy 88). A dowry was a case of luxury items and cash a bride’s father exchanged with her groom. Upper-class Renaissance women did not work, but social norms required she wear ostentatious clothing in public. Clothing a wife was expensive, so families would often off-set the cost by providing the young bride with a set of clothing and jewelry to start her new, married life. In early modern Italy, it was possible for a woman to regain her dowry after her husband’s death, the first time in her life that she had access to its wealth. Paintings like this, therefore, may be so meticulously and precisely rendered to prove what made up the dowry, should its contents ever be called into question (Murphy 88).

Together, these images explain how fashion was bound up with beauty and social expectations for women. Female portraiture depicts not specific individuals, but rather their lavish clothing and jewelry. Women were meant to be decorous and decorative. Virtue, familial expectation, and attractiveness were deeply conflated. Leon Battista Alberti states in Della Famiglia, a treatise on living well (began 1432), that what makes a woman beautiful is potential fertility:

“Thus I believe that beauty in a woman can be judged not only in the charms and refinement of the face, but even more in the strength and shapeliness of a body apt to carry and give birth to many beautiful children.” (122)

In the very next line Alberti adds that “the first prerequisite of beauty in a woman is good habits” (Ibid). Alberti would have agreed with the mantra: “Beauty adorns virtue.”

References:

- Alberti, Leon Battista. The Albertis of Florence: Leon Battista Alberti’s Della Famiglia. Translated by Guido A Guarino. Lewisburg, 1971. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/924825616.

- Brown, David Alan. Virtue & Beauty: Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci and Renaissance Portraits of Women. Princeton University Press, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/931254672.

- Castiglione, Baldassarre, and Thomas Hoby. The Courtier of Counte Baldessar Castilio: Diuided into Foure Bookes. Verie Necessarie and Profitable for Young Gentlemen and Gentlewomen, Abiding in Court, Palace, or Place. Translated into English by Tho. Hobby. London: Printed by Thomas Creede, 1603. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/606505970.

- Frick, Carole Collier. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes, and Fine Clothing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62133195.

- Green, Monica Helen. The Trotula: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/45102919.

-

Landini, Roberta Orsi, and Mary Westerman Bulgarella. “Costume in Fifteenth-Century Florentine Portraits of Women.” In Virtue & Beauty: Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci and Renaissance Portraits of Women, edited by David Alan Brown, 89–98. Princeton University Press, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/931254672.

- Monnas, Lisa. Renaissance Velvets. London: V & A Publications, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/781677614.

- Murphy, Caroline P. Lavinia Fontana: A Painter and Her Patrons in Sixteenth-Century Bologna. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/470124067.

- Musacchio, Jacqueline Marie. “Weasels and Pregnancy in Renaissance Italy.” Renaissance Studies 15, no. 2 (June 2001): 172–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24438806.

- Randolph, Adrian W. B. Touching Objects: Intimate Experiences of Italian Fifteenth-Century Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/911944639.

- Steele, Valerie. The Corset: A Cultural History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/694642160.