A collar that stands upright on the back of the neck and opens in the front. This type of ruff was introduced to France by Marie de’ Medici in the 16th century, taking her name two centuries later.

The Details

The Medici collar is a type of ruff worn in the late 16th century and early 17th centuries (Fig. 1). The Complete Costume Dictionary (2011) defines it as a: “Standing, lace-edged ruff worn high in the back and ending in a low décolletage” (Lewandowski 189). Fashion, Costume, and Culture elaborates further:

“The ultimate extension of the ruffs, or wide pleated collars, that were so popular among the wealthy in the sixteenth century was the Medici collar. A Medici collar provided a large, decorative frame around the sides and back of a woman’s head. The collar was typically worn with a gown with a décolleté neckline, a low neckline that revealed a woman’s cleavage. Supported by wire or heavy starch, these collars of lace, embroidered satin, or some other light material could reach great heights, towering over the shoulders and head of the wearer. They might be studded with tiny jewels and could be worn with a normal ruff if desired.” (“Medici Collar”)

The Brooklyn Museum Quarterly writes about its origins:

“Marie de’ Medici, who was a niece of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, imported from her native country the costliest laces in utter disregard of the sumptuary laws restricting dealing with Italy. The upstanding ‘Medici collar,’ familiar in her portraits by Rubens, Pourbus de Younger and others, was made of choicest Venetian point…. The Medici collar was the transition between the ruff first worn by Henry II and Catherine de Medici and the wide flat collar worn by Louis XIII.” (126)

Portraits of Marie de’ Medici show her wearing increasing elaborate lace collars. While in a 1605 portrait (Fig. 4) the lace is restricted to a ruff edging attached to a linen collar, a portrait only a few years later shows what seems to be the entire collar made of lace (Fig. 6). Her daughter, Christine of France (Fig. 5), wears a more demure dress with a mostly lace collar in a 1615 portrait.

Fig. 1 - Frans Pourbus de Younger (Belgian, 1569-1622). Portrait of Maria de’ Medici, 1606-1607. Oil on canvas; 214 x 124 cm (84.3 x 48.8 in). Bilbao: Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, 84/86. Source: Wikimedia

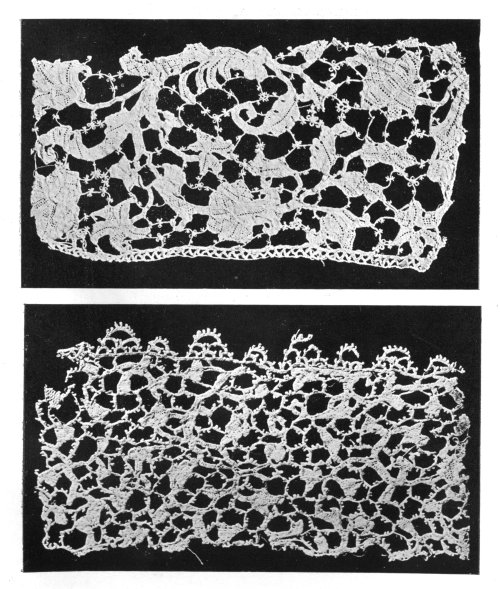

Fig. 2 - Maker unknown (Venetian). Point plat de Venise, 16th century. Emily Leigh Lowes Collection. Source: Project Gutenberg

Fig. 3 - Maker unknown (Italian). Ruff edging, 1600-1620. Needle lace worked in linen thread; length: 203 cm lace laid flat. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.14-1965. Given from the collection of Mary, Viscountess Harcourt GBE. Source: V&A

Fig. 4 - Attributed to Frans Pourbus the Younger (Belgian, 1569-1622). Portrait of Maria de'Medici, 1605. Oil on panel; 66 × 52 cm (26 × 20.5 in). Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 5 - Frans Pourbus the Younger (Belgian, 1569-1622). Christine of France (future Duchess of Savoy), ca. 1615. Source: Wikimedia

A surviving ruff edging now in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum features the sought after Venetian needle lace (Fig. 3), about which the V&A notes: “It reached the height of its popularity in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, when it was used to decorate every type of linen and in particular to draw attention to the face and throat in the form of collars.”

Emily Leigh Lowes writes in her book Chats on Old Lace and Needlework (1908), about the Venetian laces (Fig. 2):

“These Italian laces were admired and purchased by all the European countries, and the cities of Venice and Florence made enormous fortunes. The fashions of the day led to their extensive use, Marie de’ Medici introducing the Medici collar trimmed with Venetian points specially to display them.” (53)

The Survey of Historic Costume (2010) explains the much later origin of the collar’s name:

“During the 18th and 19th centuries, revivals of this style were called Medici collar after de’ Medici queens of France, Catherine and Marie, in whose reigns this style was popular.” (Tortora 220)

Fig. 6 - Detail of Fig. 1. Frans Pourbus de Younger (Belgian, 1569-1622). Portrait of Maria de’ Medici, 1606-1607. Bilbao: Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, 84/86. Source: Wikimedia

Its Afterlife

Today, the Medici collar is an enduring item that still influences designers like Michiko Koshino and Iris Van Herpen (Figs. 7, 8). As the Survey of Historic Costume notes:

“A considerable number of details of costume that originated in the 16th century have become part or the repertory of fashion design in subsequent centuries. Some examples include the ruff and the open standing collar, later named the Medici collar.” (Tortora 226)

Fig. 7 - Michiko Koshino (Japanese, 1943-). Ready-to-Wear, Spring/Summer 2005. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 8 - Iris Van Herpen (Dutch, 1984-). Chemical Crows Haute Couture, 2008. Dubai: The Cartel Fashion Show. Source: Iris Van Herpen

References:

- Lewandowski, Elizabeth J. The Complete Costume Dictionary. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Scarecrow Press, Inc. 2011.

- Lowes, Emily Leigh. Chats on Old Lace and Needlework. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1908.

- “Medici Collar.” Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages, edited by Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast, vol. 3: European Culture from the Renaissance to the Modern Era, UXL, 2004, p. 484. Gale Virtual Reference Library.

- “Ruff Edging.” Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Accessed October 03, 2016. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O318885/ruff-edging-unknown/

- The Brooklyn Museum Quarterly, vol. 8-9. New York: The Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, 1921.

- Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010.