Since its inauguration in 1969, the Museum at FIT has presented nearly 200 fashion exhibitions incorporating themes that intrigue and inform a broad range of audiences. “Exhibitionism” features 33 of the museum’s most interesting and influential fashion exhibitions.

In celebration of its 50th anniversary, The Museum at FIT has created “Exhibitionism,” a must-see fashion exhibit covering its history of showcasing elements of historical and modern fashion. “Exhibitionism” features 33 of the museum’s most groundbreaking shows, including “The Corset: Fashioning the Body” (2000), “Gothic: Dark Glamour” (2008), and “A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk” (2013).

To convey the idea of each exhibition distinctively, the museum placed representative garments next to floor-to-ceiling photographic mises-en-scène that depicted the installation. The selection of the garments was unquestionably fitting to the indicated theme and, most importantly, appealing to the eye. As Dr. Valerie Steele told the Associated Press,

“Over the 50 years of exhibitions, fashion came to be viewed differently—as social barometer rather than just, well, clothes.”

“Exhibitionism” is living evidence of this shift in perspective, exploring the extensive history of fashion as well as its connections to history, culture, and society. This essay will focus on “The Corset: Fashioning the Body,” “A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk” (2013), and “Gothic: Dark Glamour” (2008).

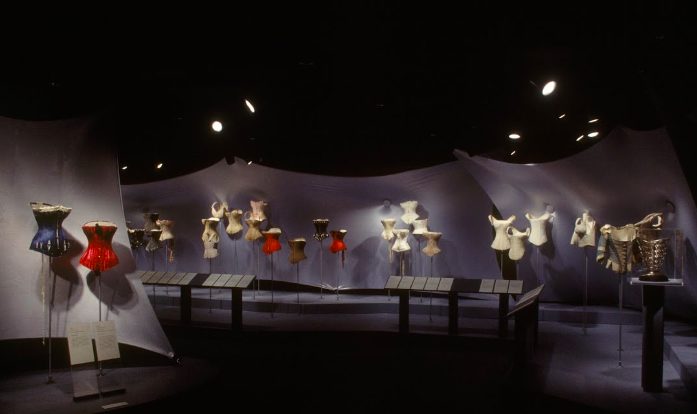

Fig. 1 - The Museum at FIT. The Corset: Fashioning the Body, 2019. Source: The Museum at FIT

Fig. 2 - The Museum at FIT. The Corset: Fashioning the Body, 2000. Source: Google Arts & Culture

“The Corset: Fashioning the Body”

This exhibition was a complete exploration of corsetry as a social construct, a fashion item, and even fetish-wear (Fig. 1). “The Corset: Fashioning the Body” was originally on view January 25 through April 22, 2000 (Fig. 2), with approximately 100 corsets and corset-inspired fashions, as well as archival photographs, posters, books, caricatures, and advertisements. The section flowed chronologically, presenting Stays (1750) (Fig. 3) and Corset (circa 1889). In the 18th century, boned stays or corsets were marks of aristocratic women, since an hourglass figure with thin waist was the “ideal” female shape that the society desired. After the French Revolution at the end of the 18th century, women temporarily gave up their corsets along with other symbols of the aristocracy. Nonetheless, corsets returned a few years later. They began to prompt concerns for women’s health—according to Addeane S. Caelleigh in Too Close for Comfort: 500 Years of Corsets,

“enumerable ills were attributed to the corset, such as tuberculosis, liver disease, and even cancer.”

The MFIT also touched upon medical horror stories in the exhibition, showing an x-ray of a woman’s ribs after years of tight-lacing her corsets (Fig. 4) and challenging viewers with such provocative questions as: “Did corsets really deform ribs and cut livers in half?” Regardless of these health risks, women continued to wear corsets to underscore the stereotypically fecund female physique.

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (French). Stays, 1750. Silk, brocade. New York: The Museum at FIT. Museum purchase. Source: Google Arts & Culture

Fig. 4 - Ludovic O'Followell (French). Padiographie du corset cambré devant (dos)., 1908. Book Le Corset. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 5 - Jean Paul Gaultier (French, 1952-). Corsets, 1990. Left: rayon, elastic net, velvet trim, metal boning, right: metallic coated warp knit, elastic, metal /. New York: The Museum at FIT. Lent by Ed Kosinski. Source: Google Arts & Culture

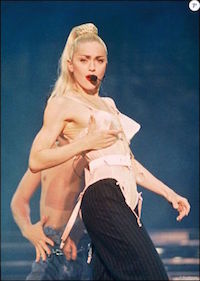

Fig. 6 - Unknown. Madonna en corset Jean Paul Gaultier lors du "Blonde Ambition Tour", à Tokyo, 1990. Source: Purepeople

Fig. 7 - Corey Sipkin. Designers Alexander McQueen (l.) and Gianni Versace were part of "A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk", 2019. Source: AM New York

In a New York Times article, “Can a Corset Be Feminist?” Alexander Fury suggested that in the 1980s:

“The sexual politics of the garment weren’t eschewed, rather they were embraced and manipulated, by a new generation of fashion designers.”

Indeed, the exhibition included corsets of the 20th century and today, including Jean Paul Gaultier’s Corsets (1990) (Fig. 5). Gaultier designed the golden corset with cone-shaped breasts for Madonna, who was instrumental in transforming the corset from a symbol of oppression into one of female sexual empowerment—she wore it on top of masculine-tailored pin striped pants (Fig. 6). In this way, the corset was made visible, functioning as a piece of clothing rather than as a shaping under layer. Today, we see incorporation of laces—often untied and unfastened—and other key details of the corset in unexpected areas of clothing.

“A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk”

This exhibition explored in-depth the notable contributions that LGBTQ (lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender-queer) individuals have made to fashion (Fig. 7), as well as the important role fashion has played within the LGBTQ community, as people developed styles that enabled them to recognize each other in an often hostile environment. One section of the exhibition explored the effects of AIDS upon fashion and design, through the lens of gay and lesbian life and culture. The exhibition addressed subjects such as androgyny, transgressive aesthetic styles, and the influence of subculture and street fashion, which are unfortunately seldom mentioned in public museums. MFIT Senior Curator of Costume Fred Dennis remarked:

“This is about honoring the gay and lesbian designers of the past and present. By acknowledging their contributions to fashion, we want to encourage people to embrace diversity.”

The pioneering exhibition in 2013-14, received several awards for transforming our understanding of fashion history.

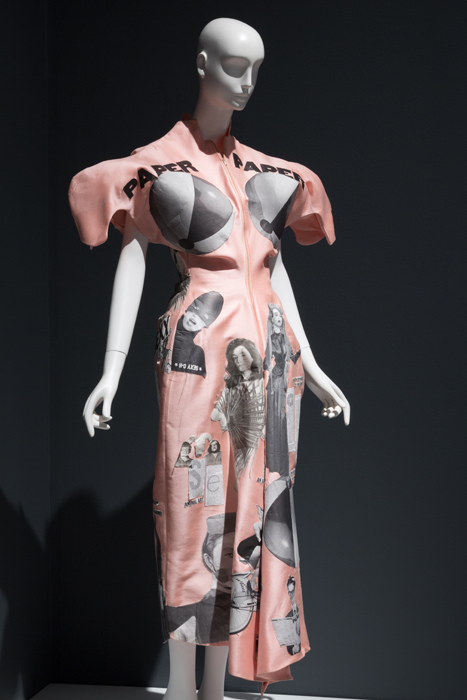

One key piece in the exhibition was Andre Walker’s Paper Dress, which was designed for the Love Ball—an AIDS benefit held in 1989. Throughout the 1980s in New York City, there was little support for those who contracted the virus as a result of the era’s discrimination against minorities, intravenous drug users and gay people. Given the high rate with which gay men died, fashion was almost brought to a catastrophic end. Members of the fashion and design industries responded to this crisis by organizing fundraisers to raise awareness for AIDS victims—the earnings were used to support research, prevention, public policy reform, and ways of assistance. For example, the Paper Dress (Fig. 8), soft pink dress with prints of photographed beach balls, models, and people and voluminous sleeves, was donated by designer Andre Walker to the Love Ball, which was one of the many AIDS benefits. Next to the Paper Dress, adorning the black walls, were the famous t-shirts with meaningful slogans such as “Read My Lips” and “Act Up.” The “Act Up” graphic t-shirt (Fig. 9) defined the AIDS/HIV activist movement in the 1980s as it represented the New York City-based organization, ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) who fought for the end of the disease by mitigating loss of health and lives. In this way, we may acknowledge the crucial role that fashion and style have played within the gay community and the AIDS crisis, which must not be forgotten.

“Gothic: Dark Glamour”

One of the most captivating displays in “Exhibitionism” was undoubtedly “Gothic: Dark Glamour” with its special mise-en-scène suggesting iconic gothic elements, such as the vampire coffin and glimmering moonlight (Fig. 10). The garments by various designers represented different outcomes from the same visual vocabulary—gothic. Originating in 18th-century literatures of terror, the gothic continued to be embraced by many people in vampire literature, cinema, and fashion. Director and curator of the Museum at FIT, Dr. Valerie Steele commented on this particular theme: “Although popularly identified with black-clad teenagers and rock musicians, the gothic has also been an important theme in contemporary fashion.”

Contemporary fashion designers, such as Rick Owens and Kate and Laura Mulleavy of Rodarte, fabricated their vision of the gothic in Ensemble with Bat Jacket (Fall 2008) (Fig. 11) and Evening Dress (Fall 2008) (Fig. 12) respectively. Attracted to the gothic’s glamorous, decadent aesthetic, Rick Owens designed this fanciful ensemble to symbolize the doomed idealism of adulthood. The ensemble’s unconventional shape and integration of different shades of black convey a dark, fearful image. The Evening Dress by Rodarte, on the other hand, took a more literal approach by connecting the dress to Japanese horror movies and by making sure that the red dye in the dress looked like blood in water. The Museum at FIT suggested:

“As a genre, the Gothic is characterized by the themes of death, destruction and decay, haunting and imprisonment…Ironically, its negative connotations have made it, in some respects, ideal as a symbol of rebellion; hence its significance for youth subcultures. Today the words ‘goth’ and ‘gothic’ are popularly associated with black-clad teenagers and mascara’d rock musicians.”

“Exhibitionism: 50 Years of The Museum at FIT” spotlights 33 of the most influential exhibitions held at the museum, including “The Corset: Fashioning the Body,” “A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk,” and “Gothic: Dark Glamour.” Dr. Steele and Colleen Hill carefully culled through costumes and accessories of the past shows, making the exhibition a crash course of sorts. Make sure to pay a visit to the Museum at FIT to see the exhibit before it closes. “Exhibitionism: 50 Years of The Museum at FIT” will be open until April 20, 2019 and The Museum at FIT is free and open to the public Tuesday through Friday from noon-8pm and Saturday 10am-5pm.

Fig. 8 - Andre Walker. Paper dress, 1989. Printed paper and synthetic twill. New York: The Museum at FIT, 89.102.2. gift of Paper Magazine. Source: The Museum at FIT

Fig. 9 - ACT-UP. Left: “ACT UP”, Right: “Safe sex is hot sex”, Left: 1990, Right: 1991. Printed cotton. New York: The Museum at FIT, Left: 90.179.1, Right: 91.143.10. gift of Richard Martin. Source: The Museum at FIT

Fig. 10 - Unknown. Gothic: Dark Glamour, 2019. New York: The Museum of FIT. Source: The Museum of FIT

Fig. 11 - Rick Owens (American). Ensemble with Bat jacket, Fall 2008. Black felted wool, denim, silk crepe chiffon, and knit. New York: The Museum at FIT. Lent by Rick Owens Corp. Source: The Museum at FIT

Fig. 12 - Rodarte. Evening dress, Fall 2008. Hand-dyed silk gauze. New York: The Museum at FIT, 2008.55.1. Museum purchase. Source: The Museum at FIT

References:

- Aizenman, Nurith. “How To Demand A Medical Breakthrough: Lessons From The AIDS Fight.” NPR.org. Accessed March 8, 2019. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/02/09/689924838/how-to-demand-a-medical-breakthrough-lessons-from-the-aids-fight.

- Caelleigh, Addeane. “Too Close for Comfort: 500 Years of Corsets.” Reshaping the Body: Clothing & Cultural Practice. Accessed March 1, 2019. http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/clothes/.

- “Exhibitionism: 50 Years of The Museum at FIT.” Accessed March 14, 2019. https://exhibitions.fitnyc.edu/exhibitionism/?url=1999-%E2%80%93-2011%3A-special-exhibitions-gallery%2Fgothic-v2-1.

- Force, Thessaly La. “Those We Lost to the AIDS Epidemic.” The New York Times, April 17, 2018, sec. T Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/04/17/t-magazine/aids-epidemic-deaths-new-york.html,

- Fury, Alexander. “Can a Corset Be Feminist?” The New York Times, November 25, 2016, sec. T Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/25/t-magazine/fashion/corset-history-feminism.html.

- “Gothic: Dark Glamour | Fashion Institute of Technology.” Accessed March 8, 2019. https://www.fitnyc.edu/museum/exhibitions/gothic-dark-glamour.php.

- “Hundred-Year-Old X-Rays Reveal How Corsets Put the Squeeze on Victorian Women.” nydailynews.com. Accessed March 1, 2019. https://www.nydailynews.com/life-style/fashion/x-rays-reveal-corsets-put-squeeze-victorian-women-article-1.1353935.

- “The Corset: Fashioning the Body.” Google Arts & Culture. Accessed March 1, 2019. https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/ywLSW2u2jYt1Kw.