An ancient Greek garment created from a single piece of cloth wrapped around the body and held together by pins at the shoulders.

The Details

T

he Berg Dictionary of Fashion History dates the chiton to ca. 480–323 BCE and defines it as:

“The ancient Greek garment formed from one piece of cloth wound round the body and held by a pin at the shoulder, or two pieces of cloth fastened along their top edges at the shoulders and down the arms. Both types could be held by a girdle below the breasts or round the waist.

The depiction of this garment has inspired later designers and makers; the chemise dress and Fortuny’s Delphos dress owe much to this style.”

According to Margaret Stavridi and Faith Jaques, co-authors of The History of Costume (1968), the chiton was “the simplest garment … a long shift for women and older men, and a short one for the young men” (6). In order to properly wrap the material for the chiton, the process was quite extensive. First, the material was: “folded in two and passed round the body, under the arms, with the opening at the right side. It was then pulled up, back and front, at equal distances from the sides and fastened on to each shoulders leaving the arms free, and girdled round the waist” (Stavridi 6).

In their Survey of Historic Costume (1998), authors Phyllis Tortora and Keith Eubank state that there were variations in the way that the chiton was styled, which was “often achieved by belting the chiton at any of several locations, by creating and manipulating a fold over the top of the fabric and by varying the placement of the pins at the shoulder” (53). In addition, “Greek men and women placed shawls or cloaks” over the top of the chiton for both decorative and utilitarian purposes (Tortora 53).

Mireille M. Lee describes the chiton in more detail in the Berg Fashion Library’s Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, writing:

“The garment worn closest to the body is a sleeved linen tunic conventionally known as the chiton. The full-length chiton was worn by both men and women in the early archaic period, but, by the middle of the sixth century b.c.e., the men’s version was shortened to the knee, probably as an accommodation for a new type of military armor. The shorter men’s chiton was called a chitoniskos or ‘little chiton’. By the middle of the fifth century b.c.e., young men rejected the chiton altogether, while older men retained the long chiton as a status symbol. The chiton was originally adopted from the East and seems to have connoted luxury and leisure in all periods, its fine white fabric and long flowing sleeves being inappropriate for manual labor.”

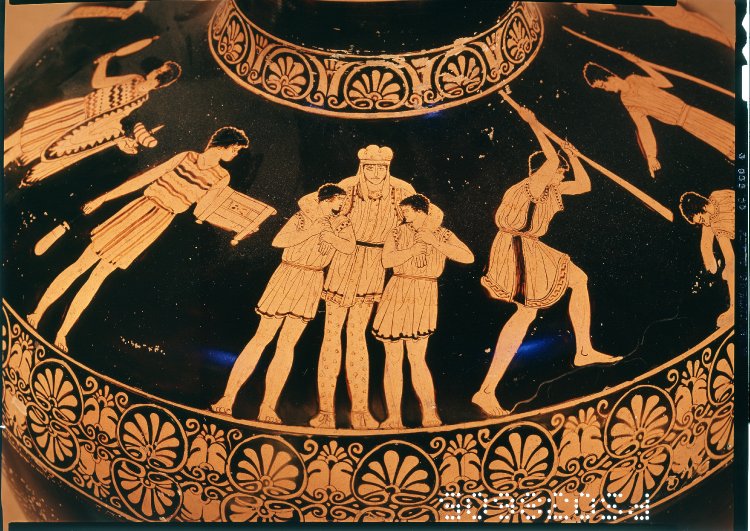

Unfortunately, there are no surviving chitons from ancient Greece, but artwork produced at the time allows us to have an understanding of the garments and its function. The chiton was a draped garment, as many Greek garments were. It was wrapped around the body, pinned at the shoulders and tied at the waist, as you can see in figures 1-6. More often, it is shown as a female garment. Many men wore it also, as it was a normal day-to-day outfit for all to wear in the 6th and 5th centuries (Figs. 3-4). The caryatids on the Erechtheion temple on the Acropolis in Athens all wear chitons (Fig. 6).

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown (Greek, Attic). Marble statue of a woman, late 4th century BC. Marble; 181.61 cm (71 1/2 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 10.210.21. Rogers Fund, 1910. Source: The Met

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown (Roman). Ten marble fragments of the Great Eleusinian Relief, ca. 27 BC – AD 14. Marble; 227 cm (89 3/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 14.130.9. Rogers Fund, 1914. Source: The Met

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (Greek, Attic). Hydria, 440 BCE. Pottery; 45.72 cm. London: British Museum, 1843,1103.24. Source: The British Museum

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (Greek). Statue of a youth, Early 5th century BCE. Limestone; 111.4 cm (43 7/8 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 74.51.2457. The Cesnola Collection, Purchased by subscription, 1874–76. Source: The Met

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (Greek). Marble statue of a woman, 2nd half of the 4th century B.C.. Marble; 168 cm (66 1/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 03.12.17. Gift of Mrs. Frederick F. Thompson, 1903. Source: The Met

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (Greek). Porch of the Caryatids, Erechtheion, 421-406 BCE. Marble. Athens: Acropolis. Source: Isabelle Duarte

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown (Greek). Eirene (the personification of peace), ca. A.D. 14–68. Marble; 177.2 cm (69 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 06.311. Rogers Fund, 1906. Source: The Met

References:

- Cumming, Valerie, C. W. Cunnington, and P. E. Cunnington. “Chiton.” In The Dictionary of Fashion History, 47. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2010. Accessed September 27, 2017. https://www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com/products/berg-fashion-library/dictionary/the-dictionary-of-fashion-history/chiton.

- Lee, Mireille M. “Ancient Greek Dress.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: East Europe, Russia, and the Caucasus, edited by Djurdja Bartlett and Pamela Smith, 442–445. Oxford: Berg, 2010. Accessed August 12, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch9085.

- Stavridi, Margaret, and Faith Jaques. History of Costume. Boston: Plays, Inc, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/919702192.

- Tortora, Phyllis G, and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume: A History of Western Dress. 3rd ed. New York: Fairchild Publications, 1998. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/39154857.