OVERVIEW

The stiff formality of 1560s womenswear, achieved through boning and high ruffs, was met by equally high collars on men, who also wore increasing pumpkin-sized melon hose and doublets with padding at the front belly.

Womenswear

Dress elements for women remained the same as in earlier decades: a chemise/shift topped by a dress bodice that usually included boning to create the desired flattened silhouette. An outer robe could be worn (closed or open), often with undersleeves and kirtle/skirt in a coordinating fabric. In the 1560s sleeves were generally narrow and ruffs small.

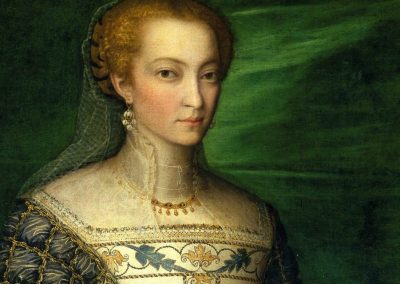

In Italy

Women’s dress bodices remained high and close about the neck everywhere except in Italy, where low necklines ruled. Indeed, as Millia Davenport notes in The Book of Costume (1948), “The very low décolletage is opening wider,” as can be seen in Titian’s Portrait of a Woman in White (Fig. 1) (501). Her bodice narrows to a point and features lacing across the front; the armscye has slipped nearly off the shoulder, where puffs of chemise emerge atop very narrow sleeves, save for at the top of the arm. A very similar dress, though in red velvet, features in Bernardino Licinio’s portrait of a family (Fig. 2). Here the sheer partlet that fills in the low neckline has added floral embroidery.

In Giovanni Moroni’s portrait of a woman in a red dress (Fig. 3), you can see not only a decorated sheer partlet, but also the embroidered edge of her chemise beneath it. Her dress has the inverted V-shape opening that was typical of dresses worn with a cone-shaped Spanish farthingale, but given the loose drape of her skirts it’s likely she merely has a bum roll at her waist to create added volume in the skirt. She wears a heavy gold girdle with bells attached and carries a zibellino, or marten fur pelt.

Fig. 1 - Titian (Venetian, 1488-1576). Portrait of a Woman in White, ca. 1561. Oil on canvas; 102 x 86 cm. Dresden: Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. Source: Norton Simon

Fig. 2 - Bernardino Licinio (Italian, 1489–1565). Ritratto di famiglia, 1560. Oil on canvas; 98.5 x 111 cm (38.8 x 43.7 in). Private Collection. Source: Blogspot

Fig. 3 - Giovanni Battista Moroni (Italian, 1523-1578). Woman in a red dress, ca. 1560. Oil on canvas; 135 x 89.5 cm. Dresden: Gemäldegalerie Old Masters, Gall 176. Source: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Fig. 4 - Jacopo Zucchi (Italian, 1540-1596). Portrait of Lady, ca. 1560. Oil on canvas; (48 x 37 3/4 in). Indianapolis Museum of Art, 2016.162. The Clowes Collection. Source: IMA

Fig. 5 - Maker unknown (English). The Gatacre Jewel; The Fair Maid of Gatacre, ca. 1560. Amethyst, mounted in enamelled gold, and hung with pearls; 6.9 x 3.9 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, M.7-1982. Purchased with the assistance of The Art Fund. Source: V&A

Jacopo Zucchi’s portrait of an unknown woman (Fig. 4) features trends already seen, including gold and blackwork embroidery on her chemise, a sheer partlet, puffs of chemise at the shoulders and a golden girdle, but also wears a sheer veil and carries leather gloves. Her pearl necklace has a delicate jeweled pendant dangling from it, as was fashionable in this period. An example of this type of pendant survives in the Victoria & Albert Museum’s collection (Fig. 5).

In England

Of course, pendants could also be much more substantial, as in the portrait of Mary Fitzalan, Duchess of Norfolk (Fig. 6). She wears the older style of dress popular in the 1540s and 50s with funnel-shaped sleeves and large turned back cuffs, in addition to her still-fashionable Spanish farthingale. Janet Arnold remarks of the portrait in Patterns of Fashion IV: “the bobbin lace at the neck is made of white linen, purple silk and silver-gilt thread” as are the acorn-pomegranate motifs on the sleeves (55).

Fig. 6 - Hans Eworth (British, active 1540-1574). Mary Fitzalan, Duchess of Norfolk, 1565. Oil on panel; 88.9 x 71.1 cm (35 x 28 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1986.9. Paul Mellon Fund. Source: YCBA

Fig. 7 - Hans Eworth (British, active 1545-1574). Portrait of an Unknown Lady, ca. 1565-68. Oil on oak; 99.8 x 61.9 cm. London: Tate, T03896. Source: Tate

Fig. 8 - Hans Eworth (British, active 1545-1574). Portrait of a Lady of the Wentworth Family (Probably Jane Cheyne), 1563. Oil on panel; 110.6 x 79.5 cm (43 9/16 x 31 5/16 in). Art Institute of Chicago, 1920.1035. Gift of Kate S. Buckingham. Source: ARTIC

Fig. 9 - Follower of Hans Eworth (British, active 1545-1578). Elizabeth Hardwick (‘Bess of Hardwick’), Countess of Shrewsbury (1520-1608), ca. 1560-69. Oil on panel; 87.6 x 66.7 cm (34 1/2 x 26 1/4 in). Derbyshire: Harwick Hall, NT 1129165. Source: National Trust

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown. Portrait of a Young Woman, 1567. Oil on panel; 92.7 x 73 cm (36 1/2 x 28 3/4 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.444. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (British). A Young Lady Aged 21, Possibly Helena Snakenborg, Later Marchioness of Northampton, 1569. Oil on oak; 62.9 x 48.3 cm. London: Tate, T00400. Source: Tate

More typical sleeves of the era are seen in two other Eworth portraits (Figs. 7-8), which feature narrow sleeves ending in ruffs at the cuffs. Both women wear a short-sleeved black outer robe fastened to the waist, where it parts to reveal a red kirtle/skirt. The unknown woman in figure 7 has matching skirt and sleeves, and her ruff is worn closed in a figure-8 pattern. Such elaborate shapes were made possible by the use of starch and specialized ruff irons; as François Boucher notes in A History of Costume in the West (1997): “The use of starch paste dated from 1564 in England, where it had been introduced by a Dutchman: Queen Elizabeth engaged a Fleming to prepare her ruffs” (244). The lady of the Wentworth family (Fig. 8) by contrast wears her ruff open at the neck and it is arranged in a more free-form pattern and features even more elaborate gold edging. Her black robe has thin hanging sleeves and is decorated with many gold and silver points or aiguillettes.

Elizabeth Hardwick (Fig. 9) wears a black short-sleeved robe similarly decorated with golden points, though her robe is lined in white fur and her sleeves are embroidered in a bright orange rather than gold. Daniel Delis Hill describes the English court’s enthusiastic embrace of color in the History of World Costume and Fashion (2011):

“By the 1560s, [Elizabeth I] had abandoned the sobriety of the dark colors and subdued fabrics of the Spanish styles adopted during Mary Tudor’s reign. Vivid colors were applied to both women’s and men’s’ apparel—crimson, peacock blue, golden ochre, and a myriad of vibrant jewel tones. Garment surfaces were variously embellished with allover decorations of embroidery, braid, pinking, sequin spangles, seed pearls, and gemstones.” (383)

Hardwick like Mary Fitzalan (Fig. 6) wears the English flattened version of the French hood popularlized by Queen Mary. An unknown woman in 1567 (Fig. 10) displays all the latest 1560s trends as Jane Ashelford explains in Dress in the Age of Elizabeth I (1988): “It was the fashion from about 1560 onwards to have a projecting wing or padded roll on the shoulder, the purpose of which was to hide the ties which united sleeves and bodice.” (13) She goes on to remark of the painting:

“The typical style of bodice and skirt worn in the 1560s can be seen in a portrait of an unknown girl … in 1567. The bodice narrows in a straight line to a point below the waist, whereas the skirt swells out with close-set pleats like a bell and is parted to show a smooth, plain underskirt.” (22)

Her partlet features a truly staggering number of small pearls, which also make up her girdle. Similar shoulder wings are featured in a portrait of Helena Snakenborg (Fig. 11), who wears a cherry red ensemble with her sleeves and chemise embellished with embroidery of bright red flowers. As Ashelford remarks in A Visual History of Costume (1983):

“The late 1560s saw a preference for brighter, fresher colours set off by enameled gold jewellery and gold braid trimming, strong naturalistic embroidered patterns and a distinctive arrangement of jewellery.” (pl. 74)

Just such an arrangement is visible here, with her gold chain necklace looped up along the top of her dress bodice and her pendant necklace pinned asymmetrically on her left breast almost like a medal. A gap at the neck of her chemise reveals another large pendant necklace, as was common at the time: “The arrangement of the partlet or chemise with standing collar undone so that a jeweled chain is exposed was very popular throughout the 1560s” (Ashelford 74).

Fig. 12 - Sofonisba Anguissola (Italian, 1530-1626). Elisabeth of Valois holding a portrait of Philip II, 1561-1565. Oil on canvas; 206 x 123 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P001031. Source: Prado

Fig. 13 - Sofonisba Anguissola (Italian, 1530-1626). Unknown Noblewoman, ca. 1560-65. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Source: Grand Ladies

Fig. 14 - Antonis Mor (Netherlandish, 1512-1576). Portrait of Margaret of Parma, ca. 1559. Oil on panel, transferred to canvas; 97.8 x 71.8 cm (38 1/2 x 28 1/4 in). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Cat. 428. John G. Johnson Collection, 1917. Source: PMA

In Spain, The Netherlands, & France

Elsewhere in Europe gowns were often worn closed, without a decorative kirtle or skirt visible. Two such gowns were painted by Sofonisba Anguissola, who served as a lady-in-waiting to Elisabeth of Valois and official court painter to King Philip II of Spain. Her portrait of Elisabeth (Fig. 12) shows her in a black gown closed by pearls and large jeweled broaches; she has extremely ample hanging sleeves that hang from her shoulders with only one broach closure on her forearm. Her high closed ruff is ornamented with lace and gold embroidery. An unknown noblewoman (Fig. 13) wears a simpler closed satin gown ornamented with foliate ribbon/braid. She wears a thin girdle without anything attached—see earlier examples for girdles with a pomander (Fig. 8) or a portrait miniature (Fig. 7) dangling. A similar thin golden girdle (though this one made of silk) survives in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum (Fig. 15).

Margaret of Parma, Governor of the Netherlands (Fig. 14), wears a silver satin gown ornamented with gold ribbon and horizontal bands on the sleeves, like Elisabeth of Valois. As Hill explains, she also wears a ropa, that is:

“a long, open-front outer gown. The design is thought to have originated in Portugal as a variation of the Moorish kaftan. The ropas were cut from a single piece of fabric shoulder to hem. Most were sleeveless with piccadils or a roll of fabric at the shoulder although some versions also had puff or funnel sleeves.” (360)

Margaret wears her ruff open at the neck, as does Claude de Beaune de Semlancay (Fig. 16).

French women continued to favor bodices with a rounded neckline that rose in the center (versus the straight cut neckline preferred by Italian women). As her outfit foreshadows, “Strong contrasts between black and white, small geometric-patterns and delicate bead necklaces were fashionable in the late 1560s” (Ashelford, Visual 72).

Fig. 15 - Maker unknown (Italian/French). Girdle, ca. 1540-80. Braided silk and metal thread; 375 x 3.8 cm. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.370-1989. Source: V&A

Fig. 16 - François Clouet (French, 1510-1572). Claude de Beaune de Semblancay, 1563. Oil on oak; 31 x 22.5 cm (12.2 x 8.8 in). Paris: Musée du Louvre, INV 3277. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 17 - Bartel Bruyn the Younger (German, 1530-1610). Catharina von Siegen, née Kannegießer, with Saint Anne and the Virgin and Child, ca. 1565-70. Oil on panel; 76.2 x 51.9 cm (30 x 20 7/16 in). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Cat. 748. John G. Johnson Colelction, 1917. Source: PMA

Fig. 18 - Lucas Cranach the Younger (German, 1515-1586). Portrait of a Woman, 1564. Oil on panel; 83.5 x 63.7 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 886. Source: KHM

Fig. 19 - Lucas Cranach the Younger (German, 1515-1586). Anna of Denmark (1532-1585), Elector of Saxony, after 1565. Oil on canvas; 214.5 x 103.5 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 3141. Source: KHM

In Germany

German women adopted elements of Spanish dress and shared their enthusiasm for black, as Davenport explains in reference to Bartel Bruyn the Younger’s portrait of Catharina von Siegen (Fig. 17):

“Spanish coat-dress of velvet-edged brocade, fur-lined, over a satin underdress. This gown will be upper class wear during second half XVIc…. These gowns, moiré-lined for summer wear, are often black. Black is much worn in XVIc. Germany in contrasting textures: velvet and cloth, moiré, dull silk and brocade. Nothing could better set off the headdresses of sheer white or gold and pearled, the wonderful goldsmith work, or the color used in bodice and apron embroidery.” (409-10)

The narrow white sleeves of a woman in a Lucas Cranach the Younger portrait (Fig. 18) show the sort of decorative embroidery work in black and gold that Davenport mentions. She also wears a decorative apron and many heavy gold chains. The effect of elaborate gold embroidery on a black gown is even more dramatically illustrated in Cranach’s portrait of Anna of Denmark (Fig. 19), which features floriate and scrollwork decoration at the bottom of the skirt and on the sleeves and bodice; “Her heavy gold jewelry, pleated skirt, and hairnet with cap are typically Saxon” (Brown 95).

Fashion Icon: Robert Dudley (1532-1588), Earl of Leicester

Fig. 1 - Attributed to Steven van der Meulen (Netherlandish, active 1543-1568). Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, ca. 1560-65. Oil on oak panel; 91.2 x 71 cm. London: Wallace Collection, P534. Source: Wallace Collection

Fig. 2 - Anglo-Netherlandish School. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, ca. 1564. Oil on panel; 107 x 80 cm. Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire: Waddesdon, 14.1996. Source: Waddesdon

Robert Dudley (1532-1588) was an English statesman and long-time suitor of Queen Elizabeth I. As Ashelford notes in A Visual History of Costume:

“The Earl’s intense love of finery earned him a respected position as arbiter of taste amongst the fashionable men at Elizabeth’s court.” (87)

He dressed well even before becoming an Earl as many surviving portraits attest. One attributed to Steven van der Meulen (Fig. 1) shows Dudley in a golden doublet with an extremely high standing collar, open figure-8 ruff, and black bonnet with coordinating feathers. As the Cunningtons note in their Handbook of English Costume in the Sixteenth Century (1954), collars reached maximum heights in England in the 1560s (90). Dudley’s doublet has open seams closed by pearl broaches and pickadils on the shoulder wings and peplum. Davenport explains the origin of the term pickadil:

“Incidentally the word picadill is the diminutive of the Spanish pica (spear); it was these cut edges, according to legend, which gave the name Picadilly to the street leading to the house of the tailor who introduced the style in England.” (440)

A circa 1564 portrait (Fig. 2) shows Dudley in a doublet ornamented with horizontal stripes similar to those seen on Elizabeth of Valois (Fig. 12 above) and Margaret of Parma (Fig. 15 above). He wears large melon hose and a slight codpiece is still visible. A sword hangs at his side and he’s shown tucking a handkerchief into a pouch at his waist—perhaps a gift of the Queen. Though she never married Dudley, she was intimate with him, gifting him handkerchiefs and even tickling him in public, as Tudor Times explains:

“Robert was created Baron Denbigh and Earl of Leicester on 29th September 1564 – the queen somewhat reducing the dignity of the occasion by putting her hand into his collar to tickle his neck. She had also granted him the superb castle of Kenilworth and extensive lands in Warwickshire. That year, he was also appointed as Chancellor of the University of Oxford.”

A ca. 1565 portrait (Fig. 3) shows Dudley in a leather jerkin with slashing across the torso and prominent pickadils at the peplum and shoulder wings. His red satin doublet sleeves are methodically slashed and pinked. The band strings of his open figure-8 ruff hang down near his chin—this was a fashionable choice at the time, as the Cunningtons note: “The Small Ruff, whether attached to the shirt or separate, was usually worn open in front, with the band strings untied and left dangling or pushed out of sight.” (112)

A smaller bust-length portrait (Fig. 4) likely based on the previous one omits the band strings and gives the Earl a slightly more youthful appearance. A less fine copy (Fig. 5) restores the band strings, but changes the doublet/jerkin to be black. As Elizabeth’s favorite, Dudley had a vast influence at court and also on English court fashion, which he helped establish.

Fig. 3 - Steven van der Meulen (Netherlandish, active 1543-1563). Robert Dudley, first Earl of Leicester (1532-1588), ca. 1565. Oil on panel; 90.2 x 72.4 cm (35 1/2 x 28 1/2 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.445. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

Fig. 4 - Anglo-Netherlandish School. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, ca. 1565-70. Oil on panel; 45.3 x 33.4 cm. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 3017-4. Felton Bequest, 1953. Source: NGV

Fig. 5 - British School. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, ca. 1565. Oil on panel; 49 x 37 cm. Derbyshire: Hardwick Hall, 1129154. gift to the National Trust with Hardwick Hall, 1959. Source: ArtUK

Menswear

The standard elements of 1560s menswear were fairly constant across Europe: a shirt, topped with a doublet, then a jerkin, perhaps then a cloak or cape. Men wore trunk hose, particularly paned melon hose with stockings. The differences were in the details and in choices of accessories like hats. For discussion of men’s fashion in England see the description of Robert Dudley above. Dudley aside, who should represent a national style is somewhat complicated to determine due to the mobility of the aristocracy in this period.

Take, for example, Alessandro Farnese, an Italian nobleman, son of Margaret of Parma (Fig. 15 above), herself the illegitimate daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Farnese was educated at the Spanish court and then went to the Netherlands with Margaret when she became Governor there. He wears Spanish fashions in a Sofonisba Anguissola portrait of ca. 1560 (Fig. 1). He sports a golden jerkin “with the highest of Spanish collars, open in the front in the manner of the 60s and after” (Davenport 463). His doublet sleeves are regularly banded and paned. His ample melon hose have gold embroidered panes, with white satin lining fabric visible in the gaps. He then “wears the cloak with hanging sleeves slung like a cape across one shoulder, as it is usually carried; it has a high collar and is notched into the beginning of our lapels” (Davenport 462). The cloak is embellished with pearls and is lined with ermine. As Ashelford summarizes in Dress in the Age of Elizabeth I:

“The whole effect is one of sumptuous elegance achieved by perfect cut and by using the richest fabric which needs no further ornamentation.” (53)

Fig. 1 - Sofonisba Anguissola (Italian, 1532-1625). Portrait of Prince Alessandro Farnese (1545-1592), later Duke of Parma and Piacenza, ca. 1560. Oil on canvas; 107 x 79 cm. Dublin: National Gallery of Ireland. Source: National Gallery

Fig. 2 - François Clouet (French, 1510-1572). King Charles IX of France (1550-1574), 1569. Oil on canvas; 224 x 116.5 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 752. Source: KHM

Fig. 3 - François Clouet (French, 1510-1572). Portrait of a Man, called the Duc d'Alençon, 1569. Oil on panel; 35.9 x 26 cm. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, NG 2426. Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to the National Gallery of Scotland, 1984. Source: National Gallery

Fig. 4 - Alonso Sánchez Coello (Spanish, 1531-1588). Don Carlos (1545-1568), 1564. Oil on canvas; 186 x 82.5 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 3235. Source: KHM

King Charles IX of France wears similar styles in a 1569 portrait by François Clouet (Fig. 2). His doublet sleeves are pinked rather than paned and his black jerkin, ornamented with ribbons of gold embroidery, has quite a long skirt, which nearly hides his codpiece and hose. The hose have achieved vast dimensions, as Brown notes: “In France breeches were nearly spherical. A 1562 English statute legislated against ‘monstrous and outrageous greatness of hose’ and fined those who wore them too large” (101). Another Clouet portrait perhaps of the Duc d’Alençon (Fig. 3) shows very similar doublet sleeves and a sleeveless jerkin. His ruff is ornamented with cutwork and lace at the edges.

Don Carlos of Spain (Fig. 4) wears a black cloak over his yellow doublet and hose with a more prominent codpiece. The portrait also features one of the new trends in menswear, namely the peascod belly, as the Tudor Tailor explains: “The peascod belly appears in portraiture in the late 1550s as a slightly padded area, starting above the waistline, which was rounded and extended down a little lower than the natural waist.” (19) The peascod belly will continue to extend down over the next decades, eventually covering and thus replacing the codpiece.

Fig. 5 - Antonis Mor (Netherlandish, 1519-1576). Portrait of a Gentleman, 1569. Oil on canvas; 119.7 x 88.3 cm (47 1/8 x 34 3/4 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1937.1.52. Andrew W. Mellon Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 6 - Giovanni Battista Moroni (Italian, 1520-1579). The Tailor, 1565-70. Oil on canvas; 99.5 x 77 cm. London: National Gallery, NG697. Source: National Gallery

Fig. 7 - Giovanni Battista Moroni (Italian, 1520-1579). Giovanni Gerolamo Grumelli, called Il Cavaliere in Rosa (The Man in Pink), 1560. Oil on canvas; 216 x 123 cm (85 x 48 3/8 in). Bergamo: Fondazione Museo di Palazzo Moroni. Lucretia Moroni Collection. Source: The Frick

Fig. 8 - Giovanni Battista Moroni (Italian, 1520-1579). Prospero Alessandri, 1560. Oil on canvas; 105 x 84 cm. Liechtenstein The Princely Collections, GE2149. Source: Liechtenstein

Fig. 9 - Maker unknown (Florentine). Burial clothes of Don Garzia de’ Medici: Doublet with breeches, surcoat, 1562. Satin and velvet. Florence: Pitti Palace, Invv. GGC nn. 8723, 8724. Source: Uffizi

A more subdued version of 1560s menswear is seen in Antonis Mor’s portrait of an unknown gentleman (Fig. 5), where his black velvet jerkin with very high Spanish collar is slashed. His satin doublet sleeves are adorned only with slight pickadils at the cuffs. He wears two gold chains and a sword atop his very bulbous melon hose. As Hill explains,

“Styles of upper stocks evolved into voluminous variations by the second half of the sixteenth century. Pumpkin hose, or melon breeches as they are sometimes called, were constructed as a pair of padded sack-like leggings over which vertical panes of fabric were sewn.” (357)

Very similar melon hose feature in Giovanni Moroni’s portrait of a tailor (Fig. 6), though this time in a rich crimson. The tailor’s doublet is pinked all-over; he prepares to cut fashionably black fabric with chalk lines visible on it. Beneath their melon hose some men wore canions, which were close-fitting hose that bridged the gap between the melon hose and stockings. An example of canions can be seen in Moroni’s portrait of Giovanni Gerolamo Grumelli (Fig. 7)—though they are difficult to spot as they match the pink of his melon hose and stockings. You can also see the beginnings of canions in Mor’s portrait (Fig. 5). Moroni’s portrait of Prospero Alessandri (Fig. 8) features more melon hose, this time paired with a black jerkin and banded white doublet with a minimal ruffle at the high collar. Notably all these Italian men have been bare-headed (Figs. 6-8), while the Spanish and French men continued to wear the black bonnet ornamented with jewels and ostrich feathers popular in earlier decades (Figs. 1-4).

Rare surviving clothes from 1562 attest to the accuracy of silhouettes seen in portraiture. The burial clothes of Don Garzia de’ Medici (Fig. 9) include a red satin doublet with narrow sleeves and bands of horizontal decoration, as well as full paned melon hose.

Other courts were adopting these trends as well, as can be seen in the portrait of Erik XIV, King of Sweden (Fig. 10), who wears an outfit quite similar to that of Don Garzia de’ Medici, though he has an additional jerkin with open seams closed by gold broaches.

Fig. 10 - Domenicus Verwilt (Flemish, active 1556-1566). Erik XIV king of Sweden (1533-1577), 1561. Oil on oak; 103 x 69 cm. Stockholm: National Museum, NM 4617. Source: National Museum

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown. Erik Sture (1546-1567), ca. 1567. Oil on canvas; 115 x 101.5 cm. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, NMGrh 938. Source: Nationalmuseum

Fig. 12 - Maker unknown. Sture costumes, ca. 1567. Uppsala Cathedral. Source: Blogspot

Unfortunately, King Erik wasn’t known just for his fashion sense, but also for his mental illness and the brutal murders of Erik Sture (Fig. 11) and 4 other noblemen. Their clothes survive (Fig. 12), including the black doublet featured in the portrait of Erik. Notably they all wore pluderose, rather than melon hose. As the Cunningtons explain,

“pluderhose were mainly a German or Swiss form of trunk hose, worn from mid-century. They were characterized by broad panes with wide gaps bulging with masses of silk or taffeta generally overhanging the panes below. These hose might be knee length or even longer.” (118)

Another example of pluderose can be seen in Cranach’s portrait of Elector August of Saxony (Fig. 13; husband of Anna, Fig. 19 above). As Davenport remarks, “The loose, pluderose fullness between the panes of the upper hose is characteristic of Protestant German costume” (412). His ensemble is all in black with the same gold embroidered decoration seen in his wife’s dress. He wears a cloak with a large standing collar; a similar example survives in the Museum of London (Fig. 14).

Common People

Thanks to portraits like Moroni’s of the tailor (Fig. 6) and the work of Netherlandish genre painters like Pieter Bruegel the Elder, we have a better picture of what those outside of the aristocracy wore. Hill explains that many of the elements essential to aristocratic fashion were simply omitted in common dress:

“Contrivances such as the farthingale, ruffs, and huge double sleeves were accoutrement of the upper classes. Through most of the sixteenth century in Italy and Spain, women of working and middle classes wore simplified versions of the courtly styles made of coarse linen or wool. The shape of the pointed-front bodices was adapted to the cut of their dresses but without the layers of padding and the constricting corset underneath that would have impeded taking care of the tasks of daily life.” (361)

Brueghel’s Harvesters (Fig. 15) shows us field workers in only shirts and hose and none of the decorative detail so essential to aristocratic dress. The central slumped figure does enable one to see the laced construction of the codpiece, which here remained practical.

Fig. 13 - Lucas Cranach the Younger (German, 1515-1586). Elector August of Saxony (1526-1586), after 1565. Oil on canvas; 214.5 x 103 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 3252. Source: KHM

Fig. 14 - Maker unknown. Cloak, ca. 1560-1575. Silk, metal, linen; 75 x 153 cm. Museum of London, C2116. Source: Museum of London

Fig. 15 - Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Netherlandish, 1525-1569). The Harvesters, 1565. Oil on wood; 119 x 162 cm (46 7/8 x 63 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 19.164. Rogers Fund, 1919. Source: The Met

CHILDREN’S WEAR

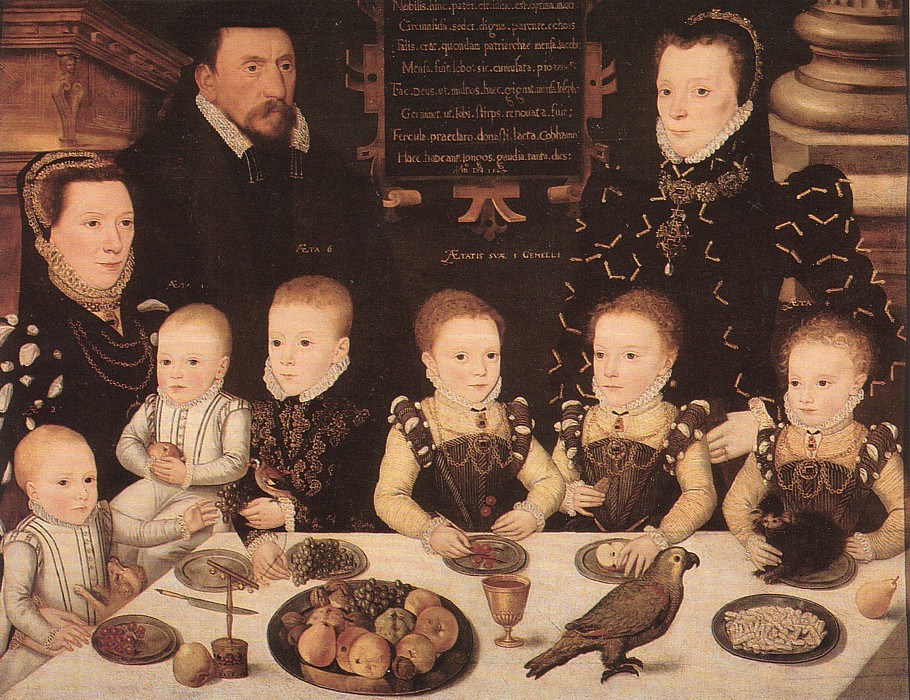

Fig. 1 - Master of the Countess of Warwick (British, active 1567-1569). William Brooke, Baron Cobham, and his family at the dining table, 1567. Source: Wikipedia

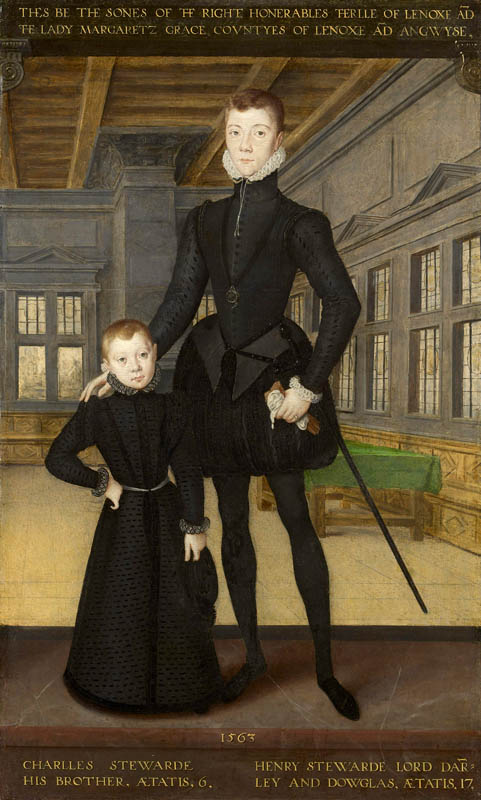

Fig. 2 - Hans Eworth (British, active 1545-1578). Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley and his brother Charles Stewart, Earl of Lennox, 1563. Oil on panel; 63.3 x 38 cm. Palace of Holyroodhouse, RCIN 403432. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 3 - Johan Baptista van Uther (Netherlandish, -1597). Crown Prince Sigismund Vasa (1566-1632), 1568. Oil on canvas; 91.5 x 56.3 cm (36 x 22.1 in). Kraków: Wawel Caste, 3221. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 4 - Workshop of François Clouet (French, 1510-1572). Hercule-François d'Alençon Duke of Alençon, Anjou and Brabant (1555-1584), ca. 1561. Private Collection. Source: Wikipedia

This progression can also be seen in Hans Eworth’s portrait of Henry Stewart and his brother Charles (Fig. 2). Henry is dressed as a man, while his little brother is still in skirts. The two-year old Crown Prince Sigismund Vasa is also still in skirts in his 1568 portrait (Fig. 3).

Two portraits of Hercule-François, Duke of Alençon (see also Fig. 3 in menswear above), allow us to see the transition from gown (Fig. 4) to miniature adult dress (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 - François Clouet (French, 1520-1572). Hercule-François, Duke of Alençon and of Anjou (1555-84), 1561. Oil on panel; 31.3 x 23.5 cm. Palace of Holyroodhouse, RCIN 403434. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 6 - Adriaen Van Cronenburg (Netherlandish, 1520-1604). Woman and Girl, 1567. Oil on panel; 107 x 78 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P002075. Source: Prado

Fig. 7 - Nicolas Neufchâtel (Netherlandish, 1527-1573). Portrait of Archduchess Anna of Austria, 1567. Oil on canvas; 67 x 49.5 cm (26.3 x 19.4 in). Warsaw: Museum of John Paul II Collection. Source: Wikipedia

Adriaen van Cronenburg’s portrait (Fig. 6) has a full mini-me effect, picturing as it does a woman and child dressed in a very similar style. The admirably self-possessed Archduchess Anna of Austria (Fig. 7) is impeccably dressed as well.

References:

- Arnold, Janet, Jenny Tiramani, and Santina M. Levey. Patterns of Fashion 4: The Cut and Construction of Linen Shirts, Smocks, Neckwear, Headwear and Accessories for Men and Women c.1540-1660. Hollywood: Quite Specific Media Group, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/909294834.

- Ashelford, Jane. A Visual History of Costume: The Sixteenth Century. London: Batsford, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/748457696.

- ———. Dress in the Age of Elizabeth I. London: Batsford, 1988. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/17981612.

- Boucher, François, Yvonne Deslandres, and John Ross. A History of Costume in the West: With 1188 Illustrations, 365 in Colour. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/443676264.

- Brown, Susan, ed. Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. New York: DK Publishing, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/840417029.

- Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Cunnington. Handbook of English Costume in the Sixteenth Century. London: Faber and Faber, 1954. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/362761.

- Davenport, Millia. The Book of Costume. New York: Crown Publishers, 1948. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/922657048.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950.

- Mikhaila, Ninya, and Jane Malcolm-Davies. The Tudor Tailor: Reconstructing 16th-Century Dress. Hollywood: Costume and Fashion Press, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/937528534.

- “Robert Dudley, Life Story.” Tudor Times. Accessed July 25, 2019. http://tudortimes.co.uk/people/robert-dudley-life-story/earl-of-leicester.

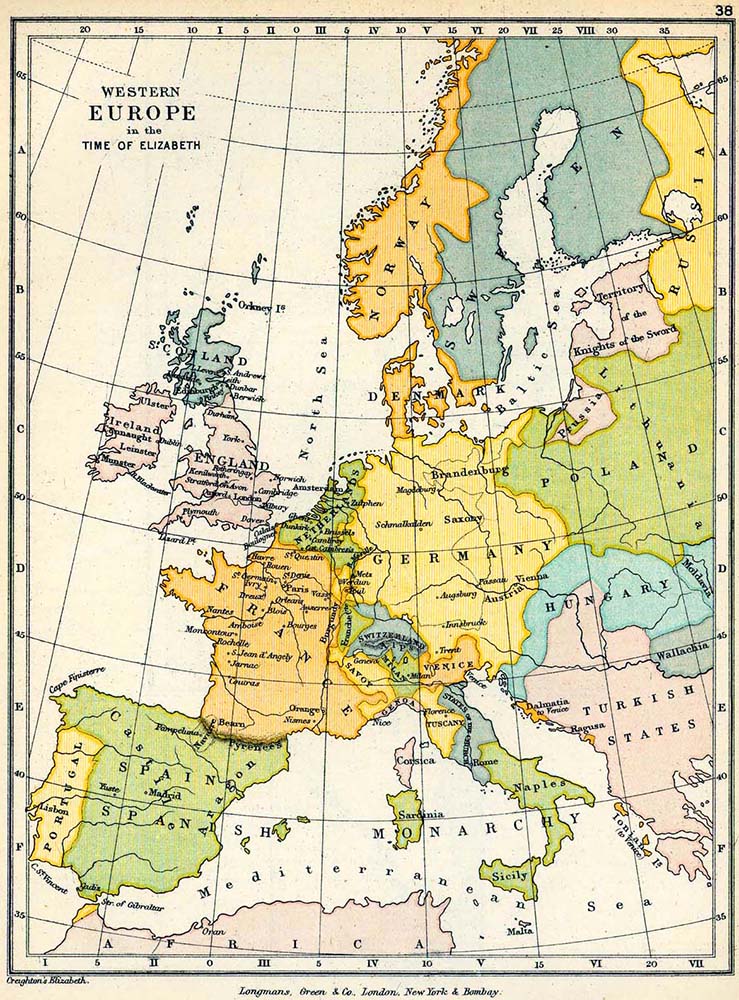

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1560-1569

Rulers:

- England: Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603)

- France: King Charles IX (1560-1574)

- Spain: King Philip II (1556-1598)

Historical Map of Western Europe in the Time of Elizabeth. Source: Emerson Kent

Events:

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 16th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.