In the 16th-century Tudor court, monarchs used portraiture to establish their ideal image—often times exaggerated and dramatized, but at the forefront of fashion.

About the Portrait

L

ucas de Heere was a South Netherlandish painter, tapestry designer, draughtsman and poet. He was trained by his artistic father, which enabled him to work in Ghent Guild of St. Luke. Art historian Carl Van de Velde describes Lucas de Heere’s artistic career through 1550-1585 as successful: “the resulting paintings and tapestries from the Ghent Guild were among the finest of their kinds.” However, de Heere was later exiled to England due to his religious and political sympathies against the Spanish authorities. During his stay in England, he was given an opportunity to paint several portraits for the English aristocracy as well as The Family of Henry VIII: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession and other royal portraits (Fig. 1) (Velde).

The National Museum Wales identifies the characters in the painting:

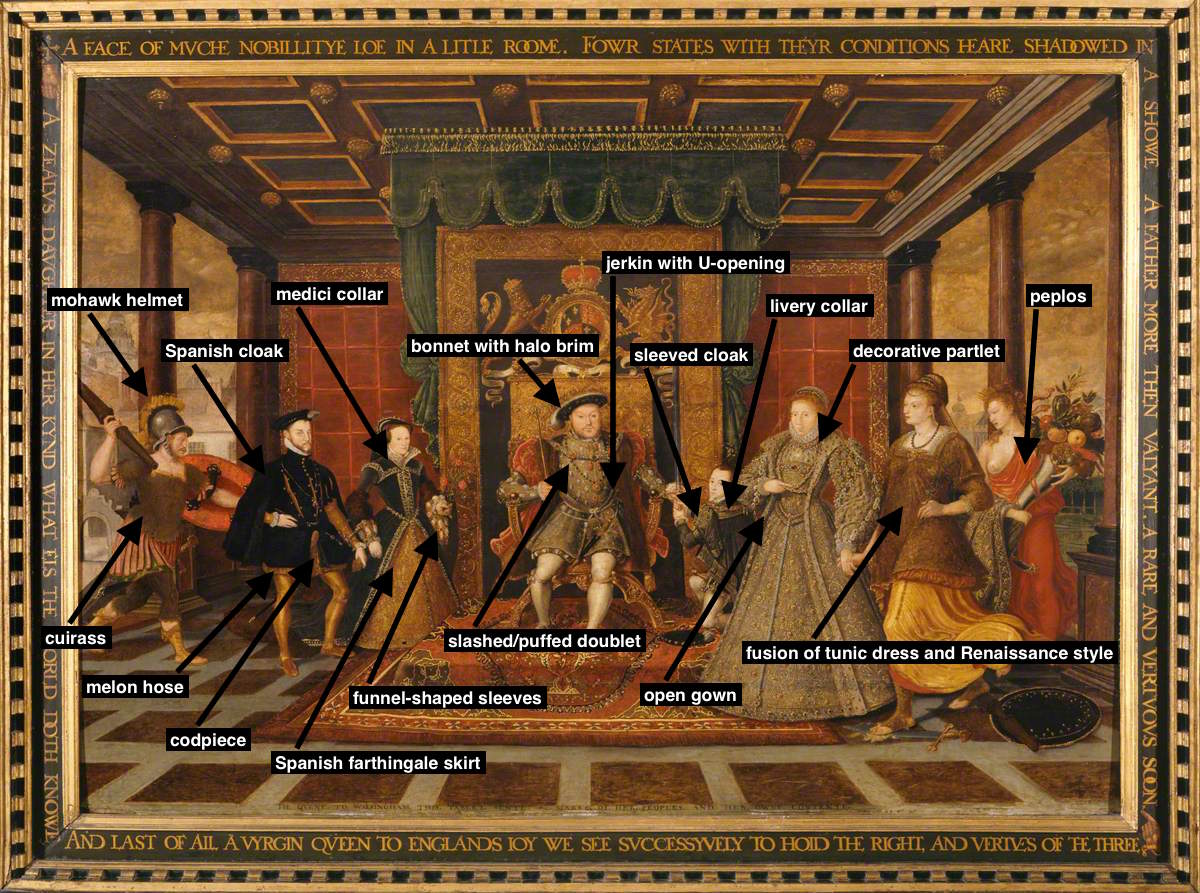

“Elizabeth is on the right, holding the hand of Pax (goddess of peace) and followed by Plenty (goddess of fertility in a flowing tunic and a peplos slipping on one shoulder. Her father Henry VIII, the founder of the Church of England, sits on his throne, and passes the sword of justice to his Protestant son Edward VI. On the left are Elizabeth’s Catholic half-sister and predecessor Mary I and her husband Philip II of Spain, with Mars (God of War) in an ancient Roman Mohawk helmet and cuirass.”

The museum also notes that the painting “exemplifies the 16th century’s fascination with allegory: the Queen’s vision of herself as the culmination of the Tudor dynasty and her concern with the legitimacy of her regime.” This painting was an exemplary portrayal of the Tudors and features the most elegant imperial fashion alongside the imagined classical divinities.

Fig. 1 - Lucas de Heere (South Netherlandish, 1534-1584). Mary I of England (1516–1558), and Philip II of Spain (1527–1598), 1558. Oil on canvas; 106.1 x 77.4 cm (41.8 x 30.5 in). London: National Maritime Museum, BHC2952. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Caird Collection. Source: Royal Museums Greenwich

Lucas de Heere (Netherlandish, 1534–1584). The Family of Henry VIII: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession, 1572. Oil on panel; 131.2 x 184 cm (51.7 x 72.4 in).Cardiff, Wales: National Museum Wales, National Museum Cardiff, NMW A 564. accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax 1991. Source: National Museum Wales

About the Fashion

P

hilip II, on the left side of the painting, is depicted in a black doublet with a row of buttons and skirt that flares out to stand over the bombasted trunk hose (melon hose), a standing high collar that reaches to his ears, a golden codpiece, and a black Spanish cape.

In In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion (2013), curator Anna Reynolds denotes the technique of “slashing,” used on Philip II’s doublet, explaining that one “way to provide a decorative surface effect was to cut into the fabric itself” (170).

Regarding the Spanish cape, dress historian Jane Ashelford explains in Dress in the Age of Elizabeth I (1988) that the way men wore their cloaks was highly dependent on which national style they preferred–Spanish, French, or Dutch. Philip II favors the Spanish fashion in the painting, showing its particular style: hooded, very full, and short (50). While Philip’s cape is black, C. Willett Cunnington and Phillis Cunnington in the Handbook of English Costume in the Sixteenth Century (1970) note that these “cloaks were often of diverse colors– some of cloth, silk, velvet, and taffeta” (106).

Very similar styles of dress can be seen in Mary I of England, 1516-58 and Philip II of Spain, 1527-98 (Fig. 1) and Portrait of a Gentleman of the order of Saint James (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 - Anton van Dashorst Mor (Netherlandish, 1519-1577). Portrait of a Gentleman of the order of Saint James, 1550. Oil on canvas; 116 x 90.5 cm (45.7 x 35.6 in). Barcelona: Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, 200703-000. Permanent loan from the Generalitat de Catalunya, Torelló settlement, 1994. Source: Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya

The Cunningtons also describe Mary I’s dress in the portrait, noting her “bodice with a high neck and medici collar, high collar partlet closed by jewelled carcanet, funnel-shaped sleeves, and Spanish farthingale skirt with a gold forepart” (153). The head accessory that Mary I wears in the painting, a French hood, is in fact an English variation– jewelled at the upper billiment (74). The funnel-shaped sleeves are “closely fitted above, expanding abruptly to a wide opening at the elbow, and finished with a broad turn-back cuff ending at the elbow bend in the front but very pendulous at the back” (152).

Mary’s dress contains elements repeated in Mary I (1516-58) (Fig. 3), Mary I (1516–1558), Queen of England and Ireland (Fig. 4), and Lady Jane Grey (Fig. 5). The notable similarities of all three portraits are the high neck Medici collar that opens at the front, and the Spanish farthingale skirts with reversed “V” openings. Most importantly, the portraits clearly depict the funnel-shaped sleeves that gradually widen from the elbows and the full, puffed under sleeves with lower slashing details and frill from chemise sleeves around the wrist.

Fig. 3 - Anthonis Mor (Netherlandish, 1519-1577). Mary I (1516-58), 1554-59. Oil on panel; 93.4 x 75.8 cm (36.8 x 29.8 in). Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, OM 53. Possibly purchased by Queen Caroline (consort to George II). First securely recorded in the Royal Collection in 1851. Source: The Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 4 - Hans Eworth (Netherlandish, 1520-1578). Mary I (1516–1558), Queen of England and Ireland, 1554. Oil on oak panel; 104 x 78 cm (41.2 x 30.7 in). London: Society of Antiquaries of London: Burlington House, LDAL 336; Scharf XXXVII. bequeathed by Reverend Thomas Kerrich, FSA, 1828. Source: ART UK

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. Lady Jane Grey, 1590-1600. Oil on oak panel; 85.6 x 60.3 cm (33.7 x 23.7 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 6804. Purchased with help from the proceeds of the 150th anniversary gala, 2006. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Reynolds additionally states that monarchs varied in their personal style and used clothing in different ways. For example, King Henry VIII, positioned in the center of the painting, was

“highly aware of the role of art, architecture and performance as a tool for propaganda, clothing constructed from rich fabrics played a vital role in the creation of both his personal image of magnificence as well as the reputation of his court as prosperous during a period of severe religious disruption.” (13)

Regarding King Henry VIII’s court attire in the painting, the Cunningtons describe each element of his clothing:

“the jerkin made with a deep U-opening to the waist in front, the gap being bridged by the slashed and puffed doublet, and the decorated doublet sleeves emerged from the gown sleeves also puffed out and hanging. The skirt is full and deep, hiding upper stocks.” (24-25)

For the last touch, he has a bonnet-style hat with a halo brim bordered with ostrich tips.

For Elizabeth I, standing on the right side and holding onto the hands of goddess of Peace, “dress was a key component in her iconography, its color and complex symbolism contributing to the cult of Virgin Queen,” according to Reynolds (13).

Ashelford describes the Queen’s partlet in the painting, that is, the decorative yoke that covers the area between the throat and the edge of the bodice; it would either be made of embroidered linen, of a rich fabric studded with jewels and pearls, or of a transparent fabric, just as shown in Mary Denton (Fig. 8) (50). Along with the partlet and the high neck ruff that Queen Elizabeth I wears, her cone-shaped Spanish farthingale and loose-bodied gown left open in the front are also evident in the painting. Such opened gown style with the rounded corner collar is also depicted in Portrait of an Unknown Lady, Aged 30 (possibly Anne Paget, d.1608) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 6 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). Portrait of Henry VIII of England, 1537. Oil on panel; 28 x 20 cm (11 x 7.9 in). Madrid: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, 191 (1934.39). acquired for the Rohoncz collection, 1934. Source: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Fig. 7 - Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497-1543). King Henry VIII, 1537. Oil on panel; 239 cm x 134.5 cm (94.1 x 52.9 in). Liverpool: Walker Art Gallery, WAG 1350. Purchased by the Walker Art Gallery in 1945. Source: Walker Art Gallery collections

Fig. 8 - George Gower (English, 1540–1596). Mary Denton, 1573. Oil on oak; 79 x 63.5 cm (31.1 x 25 in). Yorkshire: York Museums Trust, Yorag : 1137. purchased with the assistance of Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund, 1967. Source: Art UK

Fig. 9 - British (English) School. Portrait of an Unknown Lady, Aged 30 (possibly Anne Paget, d.1608), 1575. Oil on panel; 83 x 63 cm (32.7 x 24.8 in). Chippenham: National Trust Lacock Abbey, Fox Talbot Museum and Village, 996354. gift from Matilda Theresa Talbot (formerly Gilchrist-Clark), 1948. Source: Art UK

Lastly, kneeling in between King Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I, Prince Edward VI’s fashion is hardly noticeable, except the sleeved cloak with puffed out and false hanging sleeves and extremely elaborate livery collar. Livery collars or SS collars, shown in greater detail in Edward VI (1537-1553) (Fig. 10), first gained prominence when they were used by Henry IV as an official symbol of allegiance to the monarch. Edward VI continued to wear this early Tudor badge of allegiance (Merriam-Webster).

The Tudors were certainly fashion-forward and were able set an ideal image of royalty, which was often times exaggerated and dramatized. However, Ashelford explains that the ideal and mainstream fashion look of this period was also due to the rapid developments of the industry:

“Developments in fashion between 1558-1603 were characterized by the increasing preoccupation with decoration and exaggeration. This increased expenditure on clothes and a desire for imported goods transformed English fashion and English women to dress out in exceedingly fine clothes, giving all their attention to their ruffs and stuffs.” (11)

Fig. 10 - Guillim Scrots (Netherlandish, 1537–1553). Edward VI (1537–1553), 1545. Oil on panel; 58.5 x 45 cm (23 x 17.7 in). Chirk: National Trust, Chirk Castle, 1171164. purchased, 1999. Source: Art UK

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

References:

- Ashelford, Jane. Dress in the Age of Elizabeth I. London: Batsford, 1988. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/646844742.

- Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Emily Cunnington. Handbook of English Costume in the Sixteenth Century. Rev. ed. Boston: Plays, inc, 1970. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/34023831.

- “Definition of COLLAR OF SS.” Accessed November 28, 2018. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/collar+of+SS.

- Reynolds, Anna. In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/867850109.

- “The Family of Henry VIII: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession – HEERE, Lucas De.” National Museum Wales. Accessed November 3, 2018. https://museum.wales/art/online/?action=show_item&item=737.

- Velde, Carl Van de. 2003 “Heere, de family.” Grove Art Online. 22 Feb. 2019. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000037182.