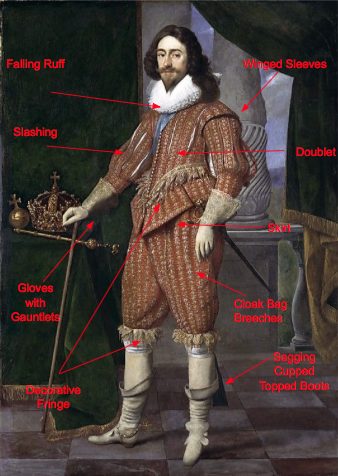

King Charles I, in a 1629 portrait by Daniel Mijtens, exemplifies 1620-30s fashions with his paned doublet, full breeches, and gloves with gauntlets made from the finest materials.

About the Portrait

T

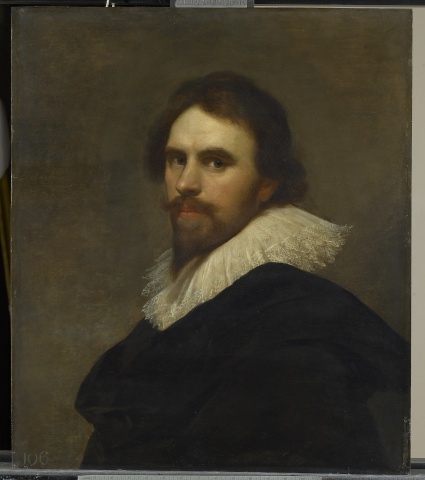

he painter Daniel Mijtens (1590-1647) was a Dutch painter of Flemish origin (Fig. 1). As art historian Rudolf Ekkart explains, he began his training in The Hague in the Netherlands, where he lived from an early age. In 1610 he joined a group of painters in The Hague. By August 1618, Mijtens began working in England where he painted portraits. Within only a few years of working in England, Mijtens had won the approval of both King James I and his son Charles, Prince of Wales (Fig. 2). In 1624 King James I granted Mijtens an annuity, which was later increased by Charles I in 1625. According to Oxford Art Online, “for most of the 1620s and in the early 1630s Mijtens was the leading court artist, as is evident from the numerous payments he received for portraits of the King or people connected with the court and for the many copies he made after the work of other artists.” It was during this time that Mijtens painted Charles I, King of England, 1629.

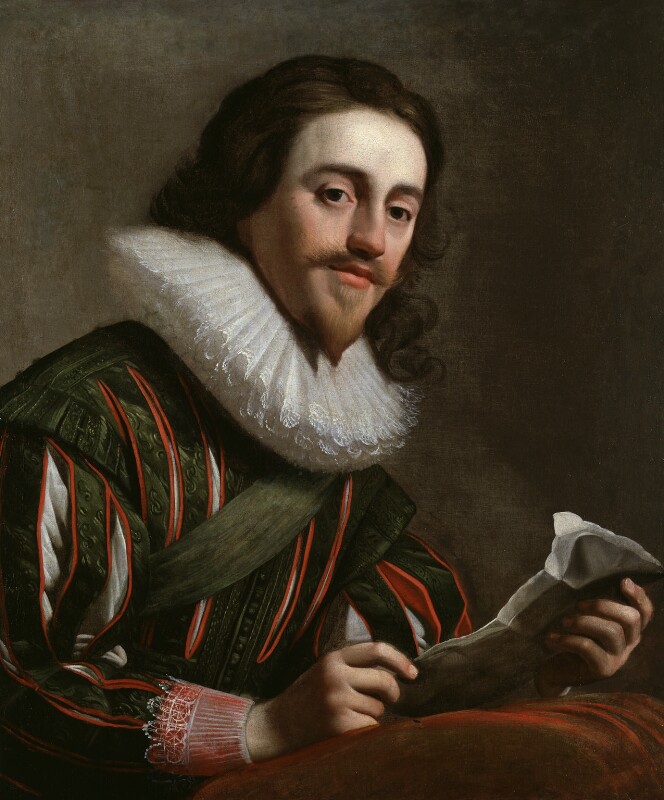

Charles I was born on November 19, 1600; he was the second son of James VI of Scotland. In 1603, Queen Elizabeth I passed away making James King of England and Ireland. Henry, Charles’ older brother, died in 1612 leaving Charles as the heir to the throne. It was not until 1625 that Charles I became King. Three months into his reign he married Henrietta Maria of France. They had a happy marriage and had five surviving children. The reign of Charles I is commonly associated with his conflicts with Parliament that led to civil war and eventually his execution. Due to his powerful position and elite status as King of England, there are many surviving portraits of Charles I, including multiple portraits painted by Daniel Mijtens (Figs. 2-5). A small replica of this portrait, but at half-length was also painted by Mijtens, who changed only the background (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 - Daniel Mijtens (Dutch, 1590-1647). Self-Portrait, 1630. Oil on oak panel; 68.3 x 58.9 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust. Source: The Royal Collection

Fig. 2 - Attributed to Daniel Mijtens (Dutch, 1590-1647). Portrait of Charles I, 17th century. Oil on panel; 35.5 x 26 cm. Source: Historical Portraits

Daniel Mijtens (Dutch, 1590–1647/48). Charles I (1600-1649), King of England, 1629. Oil on canvas; 78 7/8 x 55 3/8 in. (200.3 x 140.7 cm). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1906.06.1289. Gift of George A. Hearn. Source: The Met

About the Fashion

K

ing Charles I is painted wearing a doublet, a man’s short close-fitting padded jacket commonly worn from the 14th century to the 17th century. This is paired with cloak-bag breeches, which are commonly described as short trousers fastened just below the knee. Charles I accessorizes his outfit with falling ruff, leather boots and gloves.

The doublet displayed in the portrait is made of orange silk with “winged” sleeves, otherwise known as epaulets, that project over the ends of the shoulders giving them a broader, masculine outline with something of a military appearance (Davis 9). The sleeves are full and paned from shoulder to elbow, then closed by buttons up the back seam; similar doublets are seen in figures 3-6. The panes reveal the white of his shirt. The doublet is decorated with four to six long panes down the breast, front and back. The skirt attached to the doublet consists of deeper tabs curving down to a sharp point in the front. The two central tabs meet edge to edge. Lastly the doublet has a close row of buttons from the top of the collar to the waist, leaving the skirt unfastened.

Paired with the doublet, Charles I wears cloak-bag breeches. Cloak bag breeches are full and oval, gathering at the waist and above the knees. They are fringed with ribbon points. As fashion historians Willet and Phillis Cunnington note in their Handbook of English Costume in the Seventeenth Century (1955):

“from 1628-1635 a similar style was worn but closed just below the knee and there fastened on the outside by a ribbon rosette, or by sash garters tied in large bows. The legs were often trimmed down the outside with a vertical row of buttons and buttonholes, the lower ones sometimes being left undone to show the lining, often of linen.” (49)

Charles I wears leather rounded cup-topped boots pushed down; the same boots are seen in Figure 4. As the Cunningtons note: “The shape of the toe, in boots and shoes was rounded until c. 1635” (54). Attached to the boots, crossing the ankles in the front are spurs; indeed, “boots with spurs became fashionable for walking, from 1610 to 1660 and formed part of a gentleman’s outdoor wear” (Cunnington 57). Under the boots, Charles I wears linen white stockings.

On his hands Charles I wears gloves with embroidered gauntlets; as the Cunningtons explain, “gauntlets are made up of 6 to 8 inch sections, ending above the wrist in tabs or scallops. When embroidered this was usually done on white satin and applied.” (74) A surviving, less-elaborate pair of leather gloves with gauntlets embroidered in white silk can be seen in figure 7.

For his collar Charles I has a falling ruff. The falling ruff droops like petals of a fading flower. It is made up of several layers of linen or lawn, and usually edged with lace and gathered without formal sets. It was sewn onto a high neckband from which it sloped down to the shoulders. It was closed all around and tied by band-strings usually connected.

The cloak-bag breeches are cut full in the hips and thighs, with a moderate padding to accentuate the shape of the hips; Charles wears similar breeches in figures 3-4.

Fig. 3 - Daniel Mijtens (Dutch, 1590-1647). King Charles I, 1628. Oil on canvas; 219.4 x 139.1 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 404448. Source: The Royal Collection

Fig. 4 - Daniel Mijtens (Dutch, 1590-1647). King Charles I, 1631. Oil on canvas; 215.9 x 134.6 cm (85 x 53 in). National Portrait Gallery: London, NPG 1246. Purchased, 1899. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 5 - Gerrit van Honthorst (Dutch, 1590-1656). King Charles I, 1628. Oil on canvas; 76.2 x 64.1 cm (30 x 25.25 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 4444. Purchased with help from the Art Fund, 1965. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (French). Doublet, early 1620s. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989.196. The Costume Institute Fund, in memory of Polaire Weissman, 1989. Source: The Met

Fig. 7 - Maker unknown (British). Gloves, 17th century. Leather, silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.40.194.29a, b. Gift of Miss Irene Lewisohn, 1940. Source: The Met

The King stands full-length beside his crown and sceptre. The backdrop includes columns and a distant landscape, displaying blue skies with clouds making the viewers assume this portrait was painted during the morning. Jewel-like velvet green curtains are draped down behind the King. The emphasis of the portrait is on the rich and expensive texture of Charles’s clothing and the character of the King.

According to fashion historian Tom Tierney, under Louis XIII France had established itself as fashion arbiter of the world, and it was under his reign that Cavalier style first came into vogue–a style that would be forever linked to England’s Charles I:

“Taste began to change after the accession of Charles I in 1625. Both he and his wife, Henrietta Maria, preferred what was thought to be the more sophisticated fashions of the French court. Whilst the clothing of this period is as sumptuous and expensive as the preceding era, the elaborately embroidered textiles of the Jacobean court were replaced by plainer-looking lustrous silk satins. The padded stiffness of the Elizabethan era was replaced by a more casual, romantic look.” (51)

When ruff lost its starch and began to fall, men began to grow their hair long again. As for facial hair, clean-shaven was a common mode all throughout the seventeenth century, however, the beard of this period was called the vandyke beard (small and bristled out at the sides or curved upwards), which was worn by Charles I.

Figure 8 shows a portrait of a man, Cornelius Coning, dated 1630. Coning’s costume is similar to that of Charles I, 1629. He too wears a doublet, with panes to breast and slashing to reveal the light blue-colored lining. The doublet also has winged sleeves which project out over the shoulders. Although the doublet of Coning is almost identical to that of Charles I, the fabric of Conings’ garment are less expensive than the bright patterned and embroidered fabric used in Charles I’s doublet. Unlike Charles I, Coning wears a large hat cocked on one side, a popular hat worn in the 1620s. Around his neck, instead of the falling ruff that Charles I wears, Coning wears a falling band, a small turned-down collar with an inverted V-shaped spread under the chin and tied by band-strings.

In Figure 9, Portrait of a Young Gentleman, the young man also wears a doublet similar to Charles I. His doublet has panes to breast and slashing revealing a bright orange-colored lining. The doublet also has winged sleeves which project out over the shoulders. We can assume the man in Figure 9 is wealthier, for the fabrics used in his garment are more extravagant–the material used are patterned, and the color of the lining is brighter. He too, wears a falling ruff with lace edging, identical to Charles I.

Fig. 8 - Frans Hals (Dutch, 1583-1666). Cornelis Coning, 1630. Oil on canvas; 107.95 x 81.28 cm (42 1/2 x 32 in). Allentown: Allentown Art Museum, 1981.030. Bequest of Mrs. Joseph V. McMullan, 1981. Source: Allentown Art Museum

Fig. 9 - Jan Anthonisz van Ravesteyn (Dutch, 1570-1657). Portrait of a Young Gentleman, 1627. Oil on wood; 67.5 x 52.5 cm (26.6 x 20.7 in). Source: Artnet

Its Legacy

Chanel’s Pre-Fall 2013 collection was inspired by 17th-century fashion. Sarah Mower from Vogue states, “The interweaving of the threads of a double history—gutsy, outdoorsy, layered casualness played off against high Elizabethan-accented ruffled necklines, doublet corsets, and ballooning sleeves—gave the ‘Paris-Édimbourg’ collection a multidimensional groundedness and authenticity.” Throughout the collection Lagerfeld used embroidery in all the pieces and gold stitching–both which were crucial in the 17th century. In figures 10 and 11, the models wear cloak-bag breeches. We also see the use of winged sleeves, projecting out over the shoulders, similar to the doublet Charles I wears.

Fig. 10 - Karl Lagerfeld (German, 1933-). Chanel Pre-Fall, 2013. Model: Yumi Lambert. Photographer: Alessandro Garofalo. Source: Vogue

Fig. 11 - Karl Lagerfeld (German, 1933-). Chanel Pre-Fall, 2013. Model: Ava Smith. Photographer: Alessandro Garofalo. Source: Vogue

References:

- “Attributed to Daniel Mytens (c.1590-1647).” Historical Portraits. Accessed December 1, 2015. http://www.historicalportraits.com/Gallery.asp?Page=Item&ItemID=1808&Desc=King-Charles-I-|-Attributed-to-Daniel-Mytens

- “Charles I (1600 – 1649).” BBC News. BBC, Accessed December 1, 2015 http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/charles_i_king.shtml

- Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Cunnington. Handbook of English Costume in the Seventeenth Century. London: Faber and Faber, 1955.

- “Daniël Mijtens | Charles I (1600–1649), King of England.” Daniël Mijtens. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accessed December 1, 2015. http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/437090

- Davis, R. I., and William Landes. Men’s 17th & 18th Century Costume, Cut & Fashion: Patterns for Men’s Costumes. Studio City, California: Players Press, 2000.

- Ekkart, E. O. Rudolf, “Mijtens.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T057936pg1.

- Mower, Sarah. “Chanel Pre-Fall 2013.” Accessed December 1, 2015. http://www.vogue.com/fashion-week-review/862416/chanel-pre-fall-2013/

- Tierney, Tom. Historic Costume: From the Renaissance through the Nineteenth Century. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2004.

- Quinton, Rebecca. “The Seventeenth Century.” In Seventeenth-century Costume, 15-19. London: Unicorn Press, 2013.

- Watt, Melinda. “English Embroidery of the Late Tudor and Stuart Eras.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/broi/hd_broi.htm

- Westover, Abigail. “The Baroque Period in All Its Grandiloquence.” History of European Fashion. April 7, 2012. Accessed December 1, 2015. https://historyofeuropeanfashion.wordpress.com/2012/04/07/the-baroque-period-in-all-its-grandiloquence/