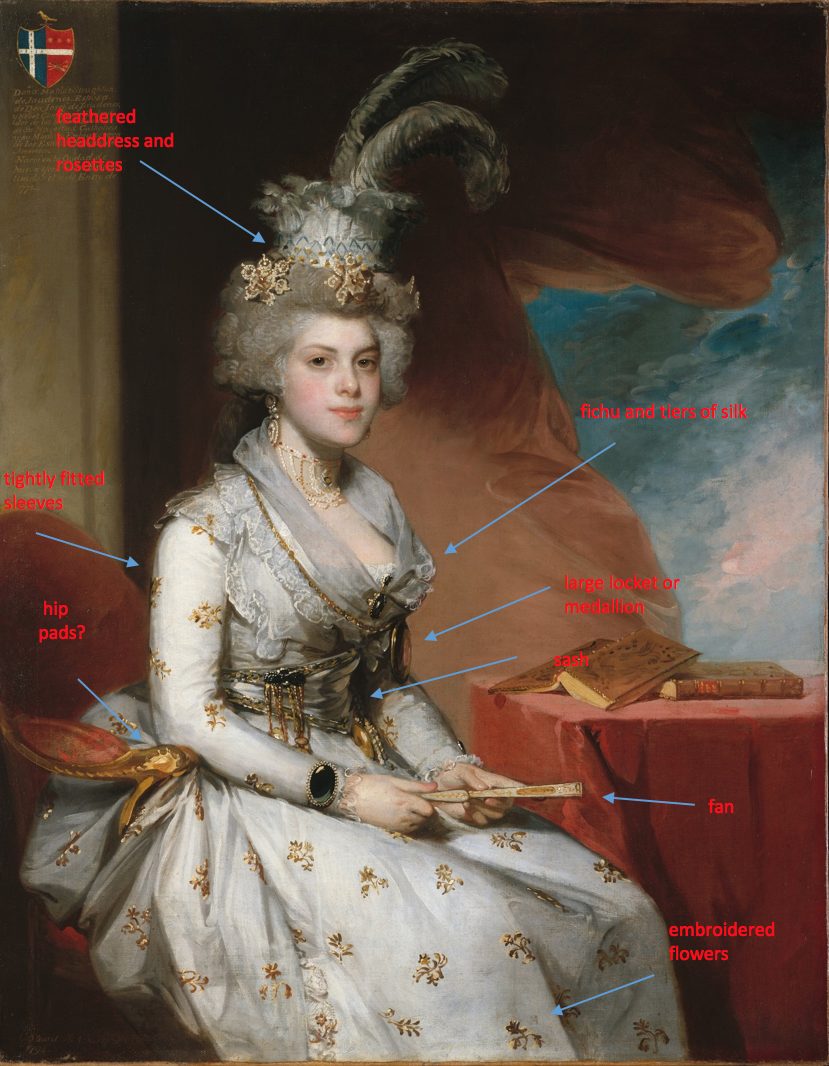

Matilda Stoughton de Jaudenes, painted by Gilbert Stuart in 1794, is dressed extravagantly at the height of contemporary style.

About the Portrait

The American Gilbert Stuart began his career in Newport, Rhode Island, but relocated to London in 1775 at age twenty where he first worked for Benjamin West. His own work in London eventually appeared at the Royal Academy. By 1794, Stuart was in New York, where he painted this portrait of Matilda Stoughton de Jaudenes.

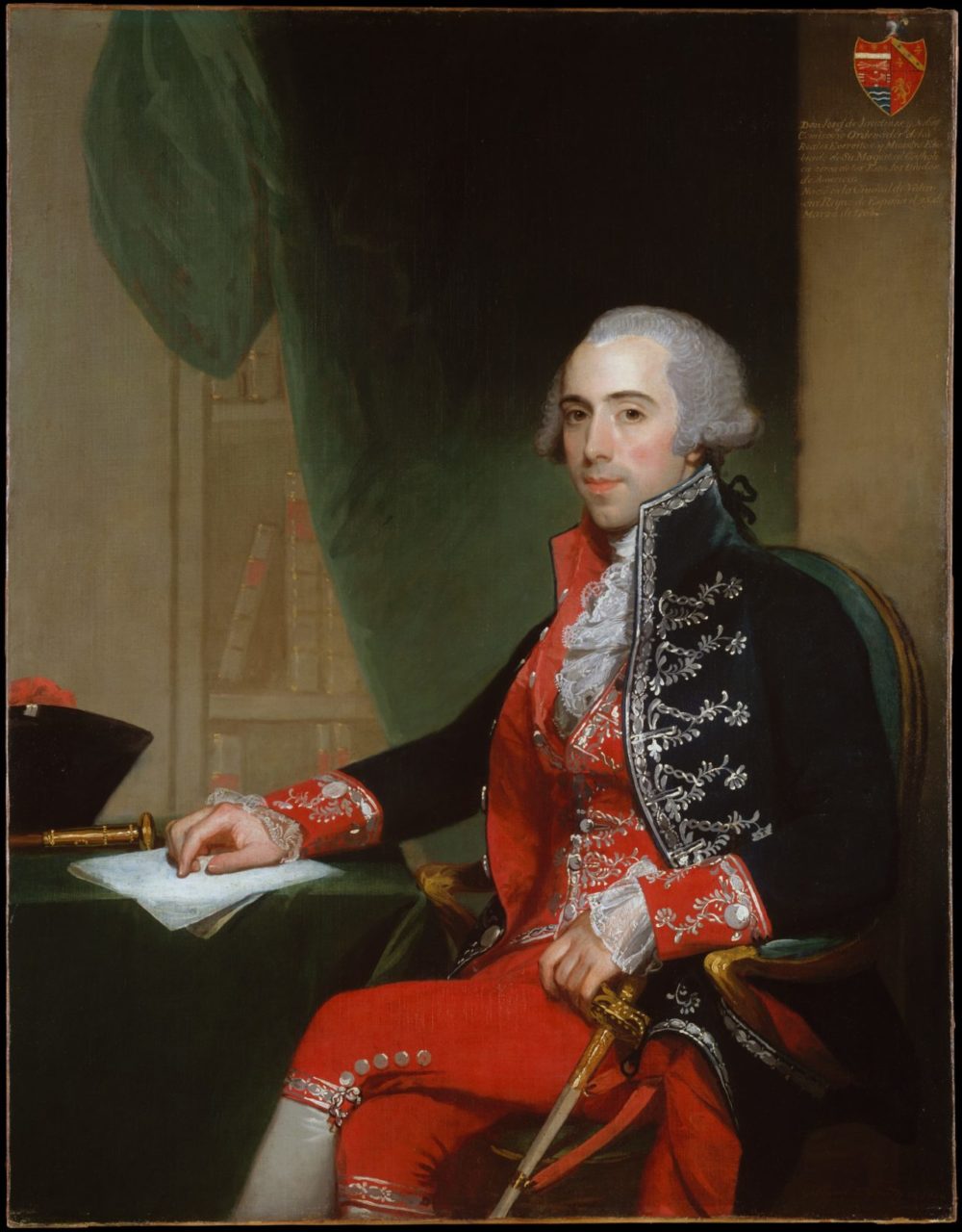

His portraits early on show a “snapshot entrapment of character” (Caldwell and Roque 1994, xxvii), and even in this portrait the sitter’s personality is apparent despite Stuart’s exact rendering of her attire (Gardner and Feld 1965, 84). But Barrett and Miles consider the sitter’s expression “vapid” (2004, 126). This portrait of Matilda Stoughton and that of her husband (Fig. 1) are done in a “Grand Manner” and are unlike Stuart’s other portraits done in America, according to McLanathan (1986, 89).

Matilda Stoughton (1778-after 1822), the sixteen-year-old daughter of Spanish consul John Stoughton of Boston is shown when she was the newly wedded wife of Josef de Jaudenes y Nebot (1764-before 1819), who was Spain’s charges d’affaires (1791-1796). After living an extravagant life in Philadelphia, the couple moved to the husband’s native Majorca in 1796 when it became clear that Jaudenes would not be envoy (Caldwell and Roque 1994, 169).

A portrait of her husband, Josef de Jaudenes y Nebot, also painted in 1794, shows him dressed as elaborately as his wife (Fig. 1). The painting is considered by Caldwell and Roque as Stuart’s “tour de force” (1994, 169). The art historian James Thomas Flexner, however, does not agree, and believes that Stuart was not engaged with either portrait (1955, 103-4).

Fig. 1 - Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828). Josef de Jaudenes y Nebot, 1794. Oil on canvas; 128.9 x 101 cm (50 3/4 x 39 3/4 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1907.07.75. Rogers Fund. Source: The Met

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828). Matilda Stoughton de Jaudenes, 1794. Oil on canvas; 128.6 x 100.3 cm (50 5/8 x 39 1/2 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1907.07.76. Rogers Fund. Source: The Met

About the Fashion

M atilda Stoughton de Jaudenes wears what is probably a robe à l’anglaise: the basic silhouette is a fitted back and a low, fitted bodice with a bit of lace chemise showing. The gown from the Metropolitan Museum’s collection that is depicted in Figures 2a and 2b is representative of this style. Note the fitted front and back of the Metropolitan Museum’s garment and the small floral decoration. Matilda Stoughton appears to wear the style that does not reveal the petticoat and has long, fitted sleeves with narrow lace at the cuffs. A contemporary fashion plate also shows narrow sleeves (Fig. 3). Matilda Stoughton’s gown was probably made of silk satin, with a pattern of small sprigs of flowers, which appear to be embroidered—the technique of painting shows light and dark highlights that give the flowers a three-dimensional look. The embroidery may indicate that the fabric was imported from Spitalfield, England, known for its fine workmanship and small floral motifs. The bodice is more difficult to describe. Fabric appears to be swathed around the figure’s stomach and bound by a sash. Surrounding her shoulders are two layers of lace-edged gauzy silk, above which is a nearly transparent fichu—all three layers might constitute one piece, perhaps. The middle figure in Figure 3 wears a similar transparent fichu, which was fashionable at the time Matilda’s Stoughton’s portrait was painted.

Under the robe à l’anglaise, is probably a chemise (see above), and most likely a corset and a bum roll to pad the hips. We do not see the bottom of the dress or the footwear in this portrait’s three-quarter view.

The sitter wears many pieces of jewelry and a fantastical feathered headdress. Chains surround her sash, and a heavy chained locket, remarked by the New York Times(1907), lies around her shoulders, terminating under her breast (but see below described as a fob). The fichu is attached with a brooch of a shape difficult to discern. Her elaborate earrings have three tiers: an oval, a flower of pearls, and then a medallion of pearls. Her necklace is a high collar of small pearls interspersed with red gems. A cascade of loops of pearls are attached with another jewel in the center. She wears a large bracelet with a stone on each wrist.

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à l’anglaise, side view, 1784-1787. Cotton, metal, silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991.204a, b. Purchase, Isabel Shults Fund and Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1991. Source: The Met

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à l’anglaise, rear view, 1784-1787. Cotton, metal, silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991.204a, b. Purchase, Isabel Shults Fund and Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1991. Source: The Met

Fig. 3 - Georg Melchior Kraus (German, 1737-1806). Journal des Luxus und der Moden, 1792-1793. Etching; 210 x 125 cm. Amsterdam: Rijks Museum, 2009. Purchased with the support of the F.G. Waller-Fonds. Source: Rijks Museum

Fig. 4 - Publisher Buisson (French). Plate 1–2 from Journal de la Mode et du Gout, Cahier 19, 25 August 1790. Etching with hand-applied color; 20 x 25.4 cm (7 7/8 x 10 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 44.2030. The Elizabeth Day McCormick Collection. Source: MFA Boston

Fig. 5 - Pyotr Gerasimovich Zharkov (Russian). Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna of Russia, 1790s. Oil on canvas. Source: Grand Ladies

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

The headdress is resembles a top hat–like structure of vertically arranged feathers, with several very long feathers curling slightly at the top, worn atop a either a wig or her own hair elaborately curled and powdered. The figure on the left in Figure 4 shows a quite similar headdress that would have been considered fashionable in 1790. Large rosettes are fastened in her powdered hair. The coiffure is similar to that of the figure on the left in Figure 4. Figure 5 shows a Russian grand duchess wearing similar rosettes in her hair. Note also that this figure of nobility is wearing a sash wrapped over her shoulder and tied at the waist. It may be that Matilda Stoughton with her similar costume was trying to emulate nobility.

The figure is holding what appears to be closed fan with a carved or painted design.

The accessories are more than what an American woman of this period would wear, however, this garment is the costume of a diplomat’s wife, whose husband is an attaché of a royal court (Caldwell and Roque 1994, 213). Caldwell and Roque state that “the diamond hairpins or piochas adorning her coiffure, the gold fob and chains encircling her waist, and well as the ivory fan . . . are typical Hispanic costume accessories” (214). The tiered earrings resemble those customary for jewelry of Spain and Portugal (McConnell 1991, 49). The Metropolitan Museum’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (under the entry “Gilbert Stuart: Matilda Stoughton de Jaudenes”) describes the gown as resembling those of Hispanic nobility.

The entire ensemble was custom-made and hand-sewed. The sitter is painted in a way that befits her status and reflects the desirable physical qualities and costume of a European woman of high status.

Its Legacy

Barratt believes that the Stuart’s portraits of prominent people, such as Matilda Stoughton and her husband, that were painted after his return to the United States paved the way for the commission of his famous portrait of George Washington (Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History).

References:

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora. “Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–present. Accessed December 4, 2015.

- Barratt, Carrie Rebora, and Ellen G. Miles. Gilbert Stuart. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004.

- Christman, Margaret C. S. “Stuart, Gilbert.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed November 13, 2015. (subscription required)

- Caldwell, John, and Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, with Dale T. Johnson. American Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, A Catalogue of Works by Artists Born by 1815. New York and Princeton, NJ: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Princeton University Press, 1994. Accessed November 5, 2015.

- Flexner, James Thomas. Gilbert Stuart: A Great Life in Brief. New York: Knopf, 1955.

- Gardner, Albert TenEyck, and Stuart P. Feld. American Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, Painters Born by 1815. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1965.

- Glasscock, Jessica. “Eighteenth–Century Silhouette and Support.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–present. Accessed December 11, 2015.

- McConnell, Sophie. Metropolitan Jewelry. New York and Boston: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Little, Brown, 1991.

- McLanathan, Richard. Gilbert Stuart. New York: Abrams, 1986.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Gilbert Stuart: Matilda Stoughton de Jaudenes” (07.76) In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–present. Accessed December 4, 2015.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Josef de Jaudenes y Nebot.” Accessed November 20, 2015.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Matilda Stoughton de Jaudenes.” Accessed October 28, 2015.

- “New Stuarts at the Metropolitan.” New York Times, May 5, 1907.

- Takeda, Sharon Sadako, et al. Fashioning Fashion: European Dress in Detail, 1700-1915. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2010.