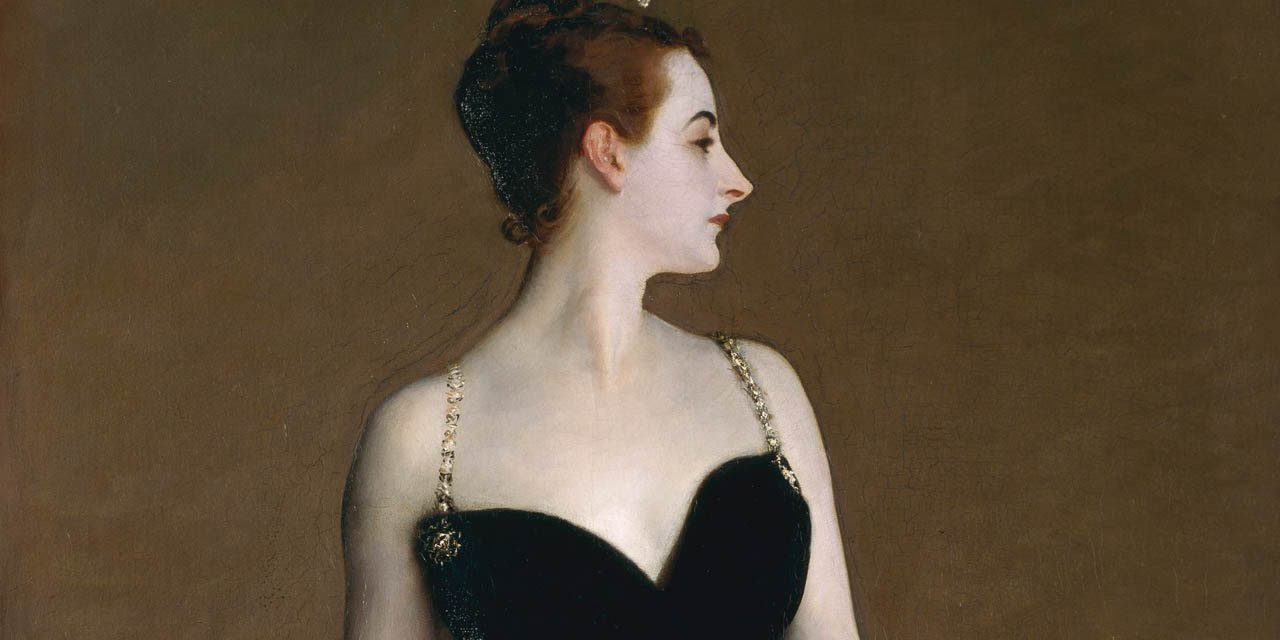

In Sargent’s most famous portrait, Virginie Gautreau, a celebrated American beauty living in Paris, dresses in daring advance of fashion–the unadorned simplicity of the dress makes it appear modern even today. Her apparent lack of underwear and daringly dropped shoulder strap (later repainted by Sargent) in combination with her heavy makeup and seeming indifference to the viewer provoked scandal when the work was first exhibited in the 1884 Paris Salon.

About the Portrait

John Singer Sargent, an ambitious young American artist, in 1874 moved to Paris, where he soon enrolled in the studio of the famed portraitist Carolus-Duran. In 1877, he exhibited his first work at the Paris Salon and gradually began to make a name for himself; his portrait of his teacher Carolus-Duran was a particular success in the 1879 Salon (Ormond, Grove).

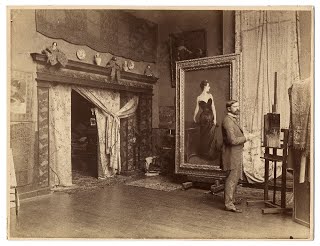

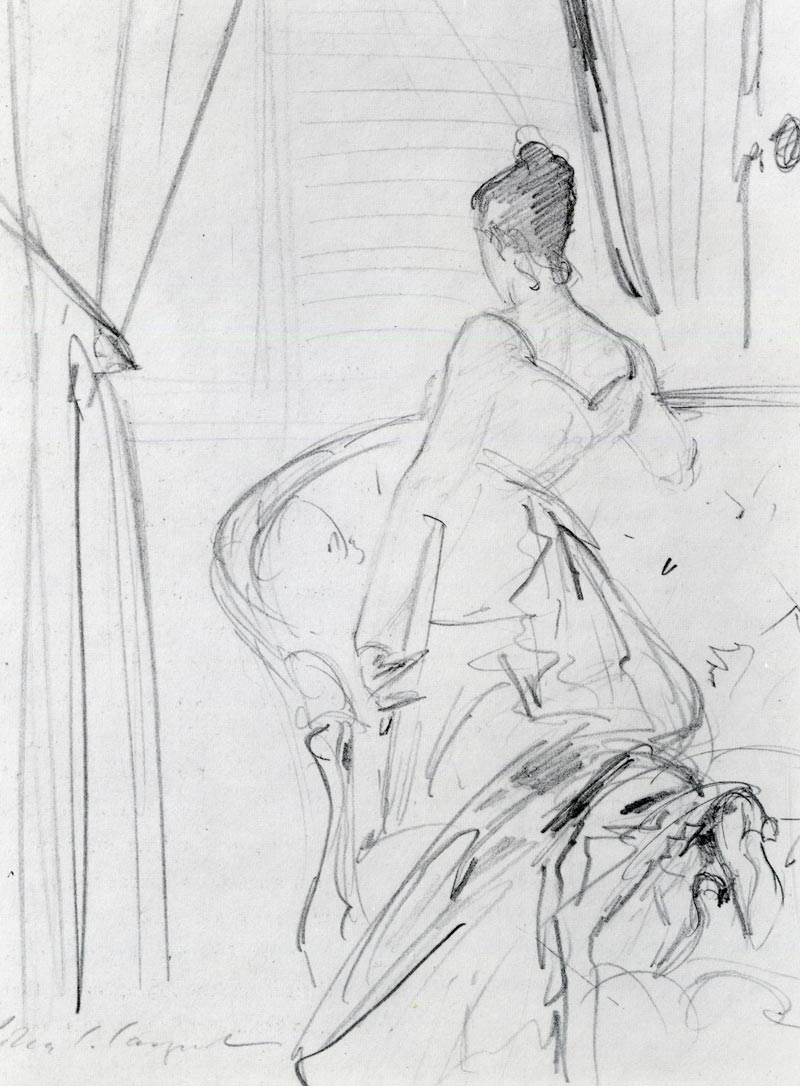

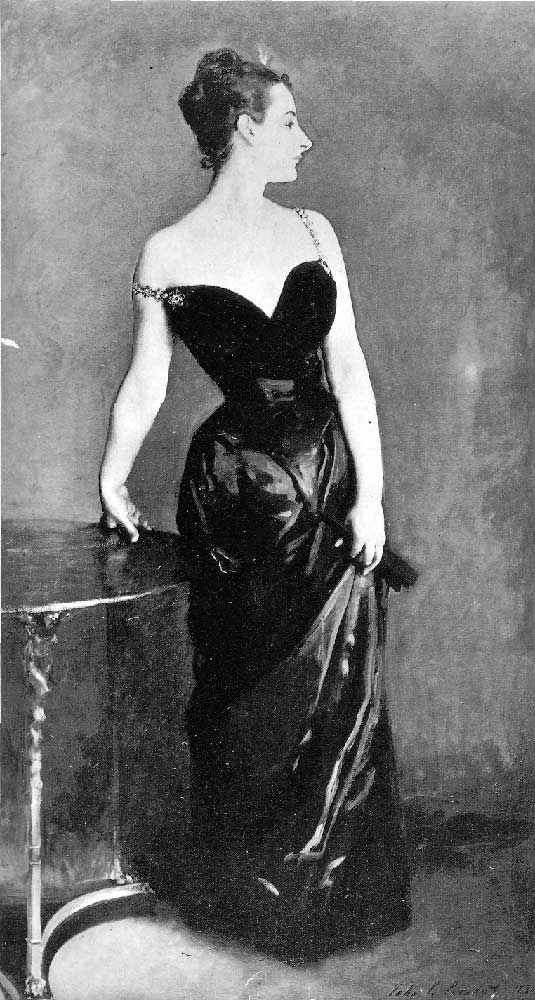

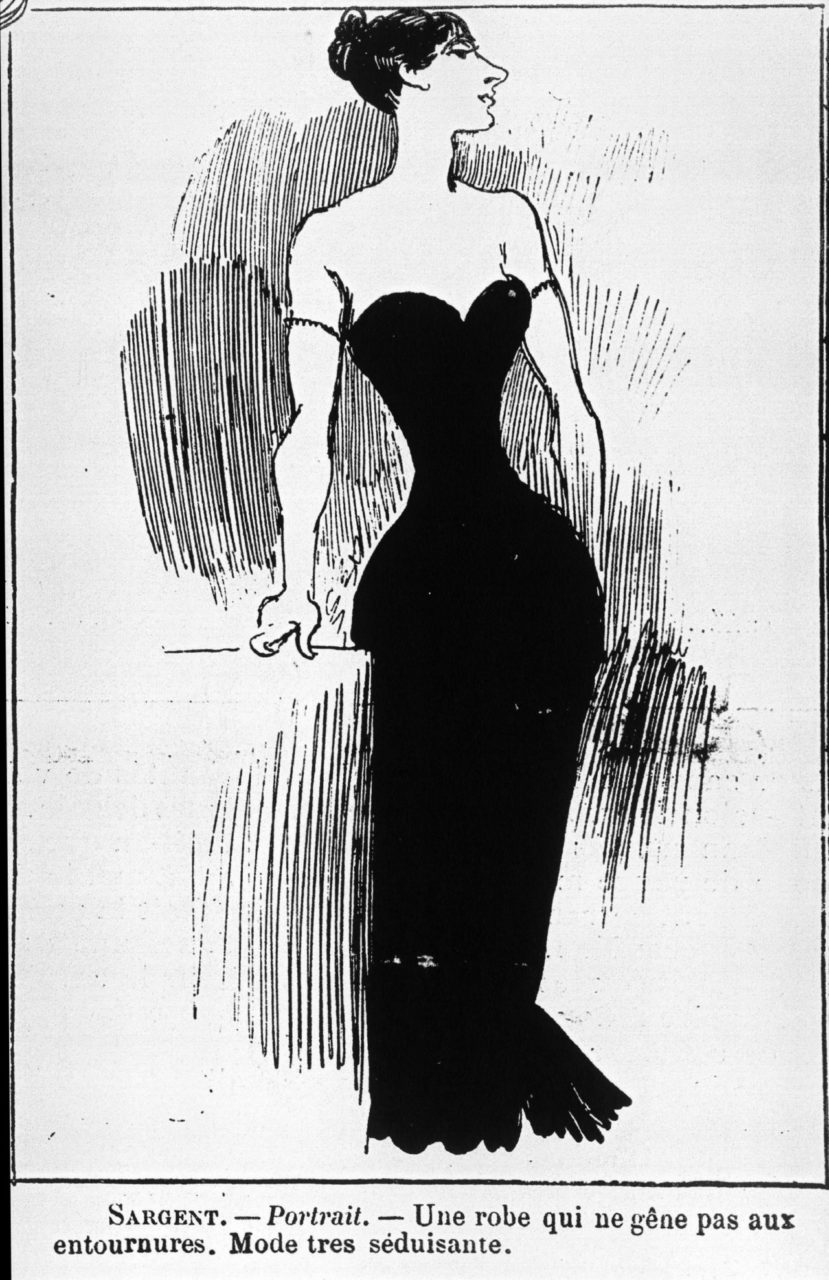

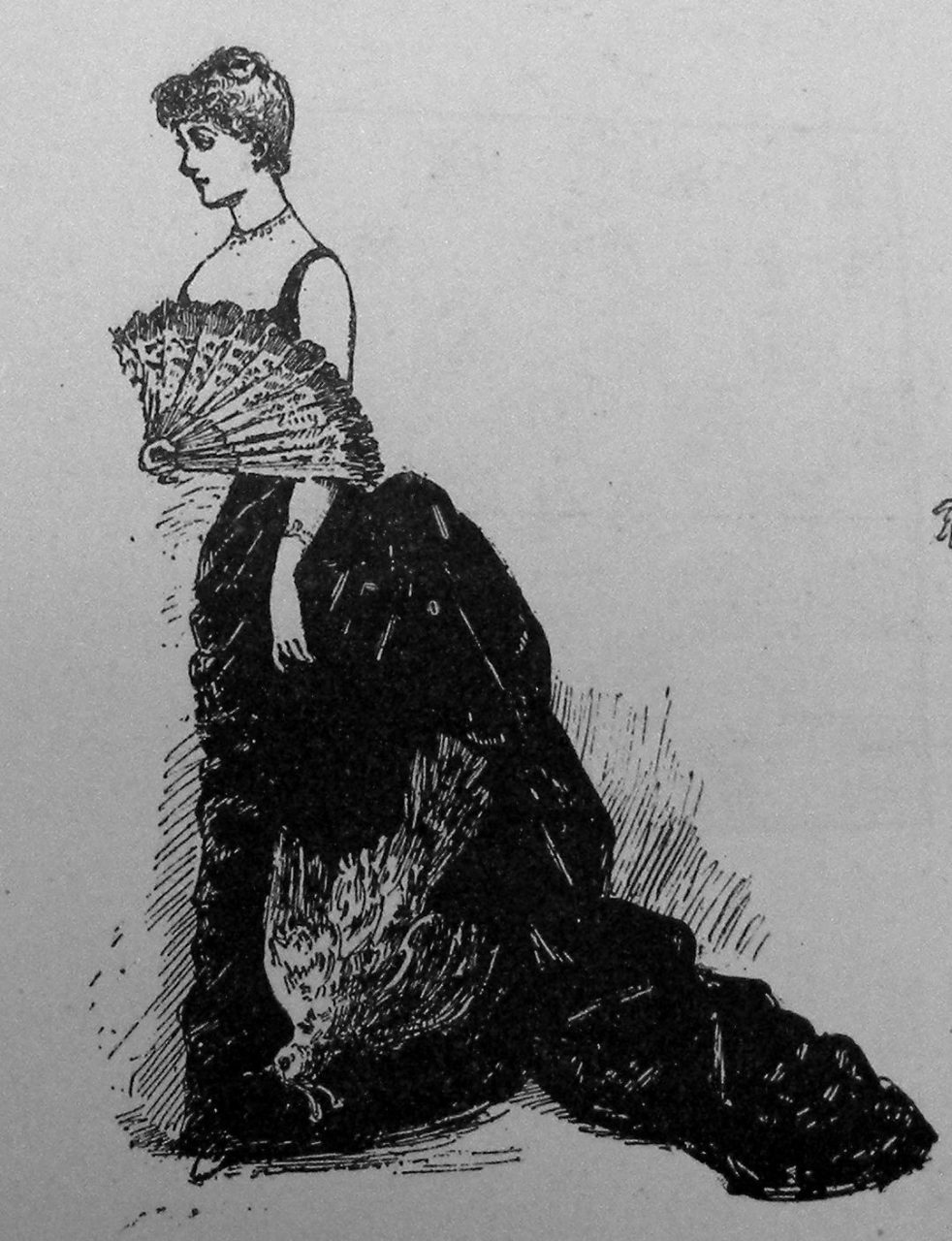

Eager to build on that success, he undertook in 1883 this uncommissioned full-length, life-size portrait of the celebrated beauty Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau (Fig. 1), an American herself who had married a successful French businessman, Pierre Gautreau. Sargent made many sketches and studies (Fig. 2) in preparation for the portrait, which caused a scandal when exhibited as Madame *** at the 1884 Paris Salon. Sargent’s original composition (Fig. 3) depicted the jeweled right strap of her dress as having slipped from her shoulder, which prompted ridicule in the press (Fig. 4) and damaged Gautreau’s reputation. Sargent thus kept the work in his studio (Fig. 5) until he sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1916, commenting:

“I suppose it is the best thing I have done.” (Metropolitan Museum 2015)

Fig. 1 - Nadar [Gaspard-Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910). Virginie Gautreau. Photograph; undated cm. Source: FindaGrave

Fig. 5 - Unidentified photographer. John Singer Sargent in his studio, ca. 1884. Source: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Fig. 2 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Study for Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau), ca. 1883. Pencil on paper; 29.2 x 21 cm (11.5 x 8.25 in). Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Jean-Marie Eveillard. Source: Wikiart

Fig. 3 - Unidentified photographer. Photograph of Madame X as exhibited at the 1884 Salon. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs Francis Ormond, 1950. Thomas J. Watson Library. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 4 - Albert Robida (French, 1848-1926). "Le Salon Comique," Caricature, no. 229 (May 17, 1884): 165. Source: BNF - Gallica

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau), 1883-84. Oil on canvas; 208.6 x 109.9 cm (82.125 x 43.25 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 16.53. Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916. Source: The Met

About the Fashion

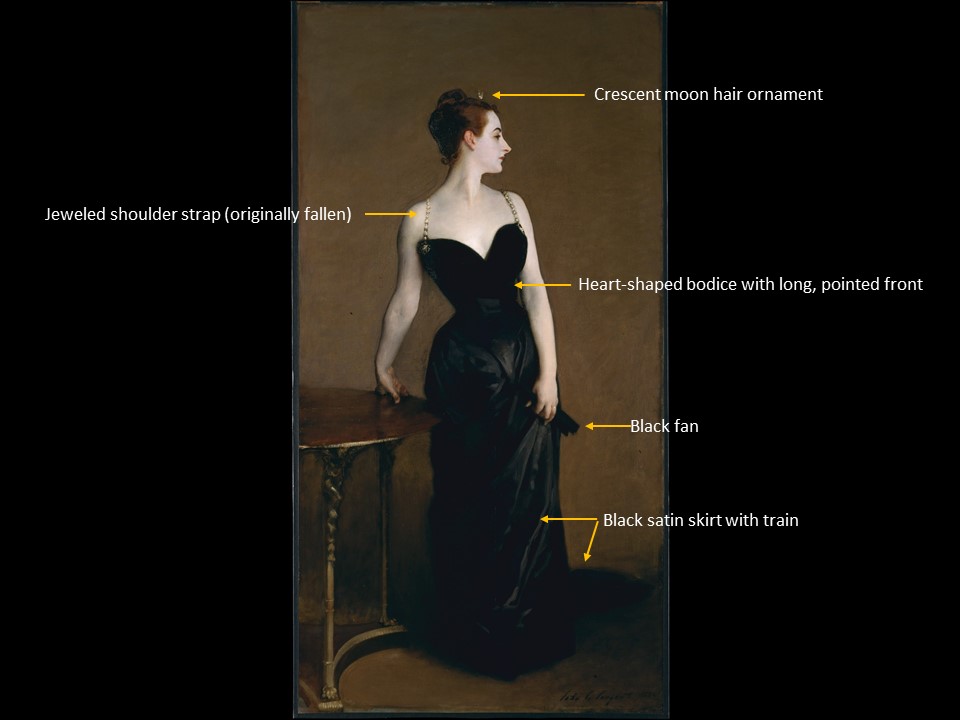

Gautreau wears a black evening dress with a heart-shaped velvet bodice with a long pointed front and a black satin skirt. Her only adornments are the dress’s jeweled shoulder straps, her gold wedding band, and in her hair a diamond crescent, likely meant to evoke Diana, goddess of the hunt (Ormond 1998). She carries a black fan and has powdered her skin to achieve an artificially white complexion (Sidlauskas 2001). This sort of elegant evening dress would be worn in Paris; from Sargent’s sketches (Fig. 2) we can see the dress featured a modest bustle and ample train and that she paired it with low-heeled pumps.

The display of such ample décolletage was not unusual and black was a popular color for evening wear as surviving portraits and garments attest (Figs. 6-9). Sargent’s contemporaneous portrait of Mrs. Alice Milbank (Fig. 6) features a perhaps even more daring décolletage and slipped shoulder strap. French artist Paul Baudry’s two 1884 portraits of Madame Thérèse Singer (Figs. 7, 8) depict her in a similar low bodice and a contemporaneous dress in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum by Hoschedé Rebours (Fig. 9) features a perhaps even more plunging neckline. Critics objected not to the display of décolletage, but the lack of fleshiness or sensuality, with one writing:

“The décolletage of the bodice doesn’t make contact with the bust, it seems to flee any contact with the flesh” (Houssaye, “Le Salon de 1884,” 589, quoted in Sidlauskas 27).

The silhouette is a very fashionable small-waisted one, likely created by extensive boning in the bodice. The dress design was undoubtedly a unique one created for Madame Gautreau herself, but by this period some of the sewing could have been done on machine. The black fan she holds could easily have been purchased at a department store.

Fig. 6 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Mrs. Harry Vane Milbank (née Alice Sidonie Vandenburg), 1883-1884. Oil on canvas; 188.6 by 90.8 cm. Private Collection. Source: JSS Gallery

Fig. 7 - Paul Jacques Aimé Baudry (French, 1828-1886). Madame Louis Singer, née Thérèse Stern, 1884. Oil on canvas; 132.5 x 85 cm. Paris: Musée du Petit Palais. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 8 - Paul Jacques Aimé Baudry (French, 1828-1886). Madame Louis Singer, née Thérèse Stern, 1884. Oil on canvas; 127 x 91.5 cm (50 x 36 in). Private Collection. Source: Artnet

Fig. 9 - Hoschedé Rebours (French). Evening dress, ca. 1885. Silk; length at cb (a): 44.5 cm; length at cb (c): 137.2 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.3304a–c. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 10 - Gustave Courtois (French, 1852-1923). Madame Gautreau, 1891. Oil on canvas; 106 x 58.5 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay, RF 3760. Source: Arthistory.us

Fig. 11 – L. Mesnil (French). “La Mode au Théatre.” La Vie Moderne 6 (February 10, 1883): 89. Source: Author.

FIg. 12 – L. Mesnil (French). “La Mode au Théatre.” La Vie Moderne 43 (October 27, 1883): 694. Source: Author.

Fig. 13 – Les Modes Parisiennes (April 1, 1881), pl. 433. Source: Author, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Gautreau was an extremely fashionable person, as Deborah Davis recounts in Strapless:

“L’Événement reported her appearance in a dress of salmon-colored velvet…. Le Figaro raved about her dress of red velvet with a bodice of white satin, as did La Gazette Rose about her white satin dress with pearl netting…. In 1880, a reporter from The New York Herald saw her in France and filed a flowery story describing her magnificence” (57).

In an 1883 column on the fashions worn by actresses on the stage (where many new styles debuted), the columnist for La Vie Moderne particularly praised that worn by Mlle Marie Magnier (Fig. 11) as the “most striking,” which in its ample décolletage, thin straps, pointed bodice, narrow-waisted columnar silhouette closely resembles Gautreau’s own dress (Magali 89).

In a later column, a different columnist praised the “superb and magisterial toilette in black velvet, the whole art of which is its magnificent simplicity,” (Fig. 12) worn by Mlle Marthe Devozod, “the prettiest woman in Paris” (Venasque 694). The thin-strapped black velvet dress closely resembles the silhouette of the similarly trend-setting Mme Gautreau. Gautreau’s dress is a dramatic simplification of a style for pointed-front bodices and narrow straps that had been recently fashionable, without the tiers of lace or decorative swags of flowers one more typically finds, as in this Les Modes Parisiennes plate (Fig. 13).

Thus, it was not the dress itself that prompted criticism, but instead her way of wearing it (with the slipped shoulder strap and heavy make-up). Also shocking was her almost certain lack of underwear:

“Heavily boned, the cuirass had a plunging neckline and came to a deep, sharp point over the crotch. ‘Though the cuirass would have had some kind of lining to soak up sweat, the model would not have been wearing any underwear,’ said Valerie Steele, director of the museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, and that would have been scandalous” (Dilberto, New York Times).

Sargent’s way of painting the portrait also created a great deal of the stir, as the contemporary critic writing for the Art Amateur emphasizes:

“This portrait is simply offensive in its insolent ugliness and defiance of every rule of art…. The drawing is bad, the color atrocious, the artistic ideal low, the whole purpose of the picture being, not an artistic and sensational ‘tour de force’ still within the limits of true art, as Sargent’s Salon pictures have hitherto been, but a willful exaggeration of every one of his vicious eccentricities, simply for the purpose of being talked about and provoking argument” (quoted in Herdrich and Weinberg 2000, 18)

Its Legacy

The portrait’s poor reception at the 1884 Paris Salon soon prompted Sargent to leave France to seek clients instead in England, where he found great success. By 1891, Gautreau had clearly changed her mind about the portrait as she commissioned a similar one from French artist Gustave Courtois that featured the same profile pose and daringly dropped shoulder strap (Fig. 10).

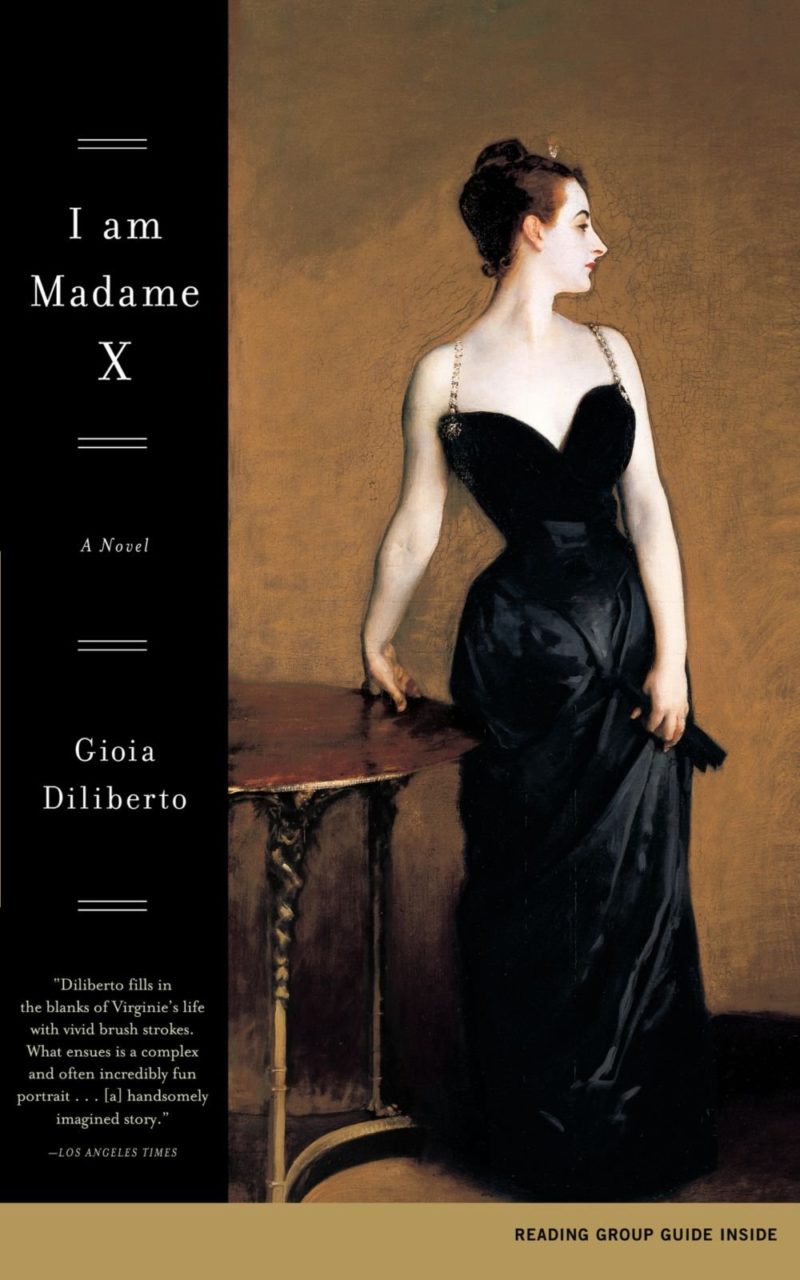

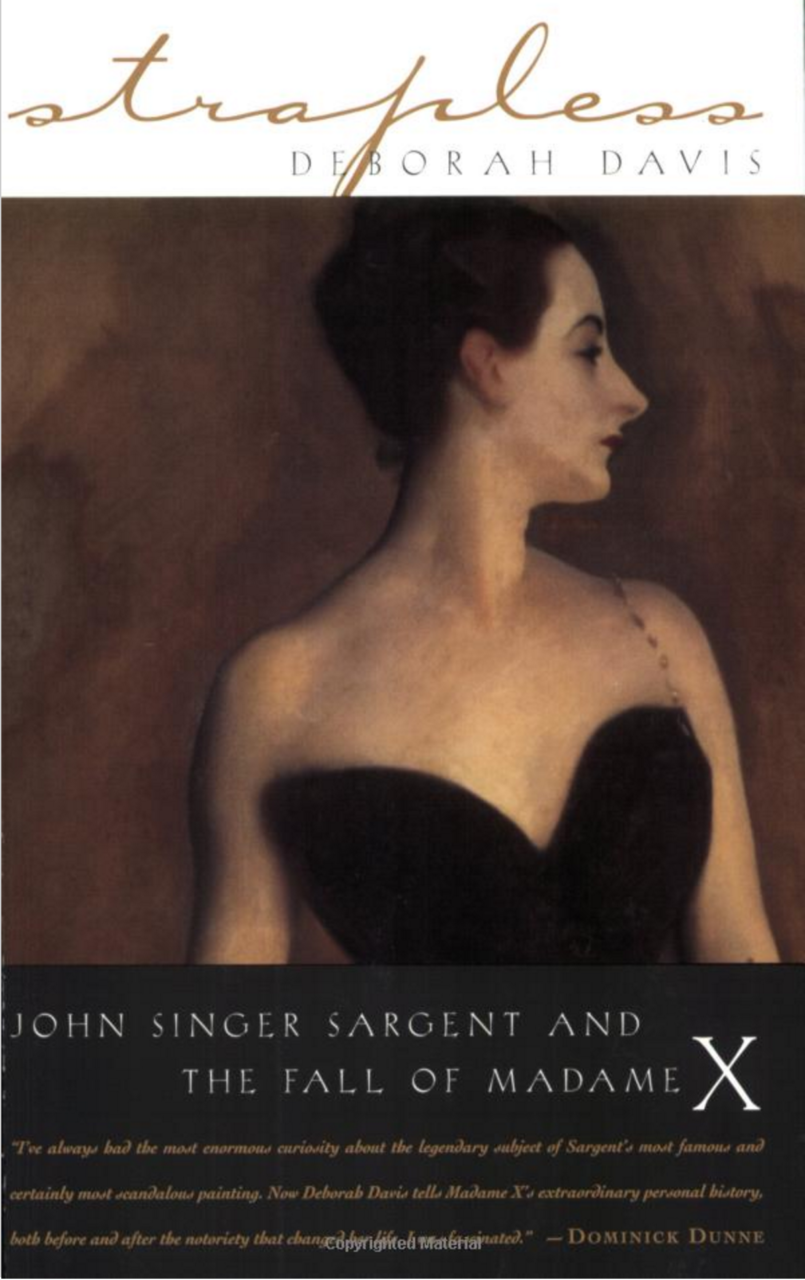

Madame X remains Sargent’s most famous portrait (Ormond, Grove) and its place in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum has kept it in the public eye since its acquisition in 1916. It has even inspired two historical novelizations, Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X by Deborah Davis and I am Madame X by Gioia Dilberto (both 2004).

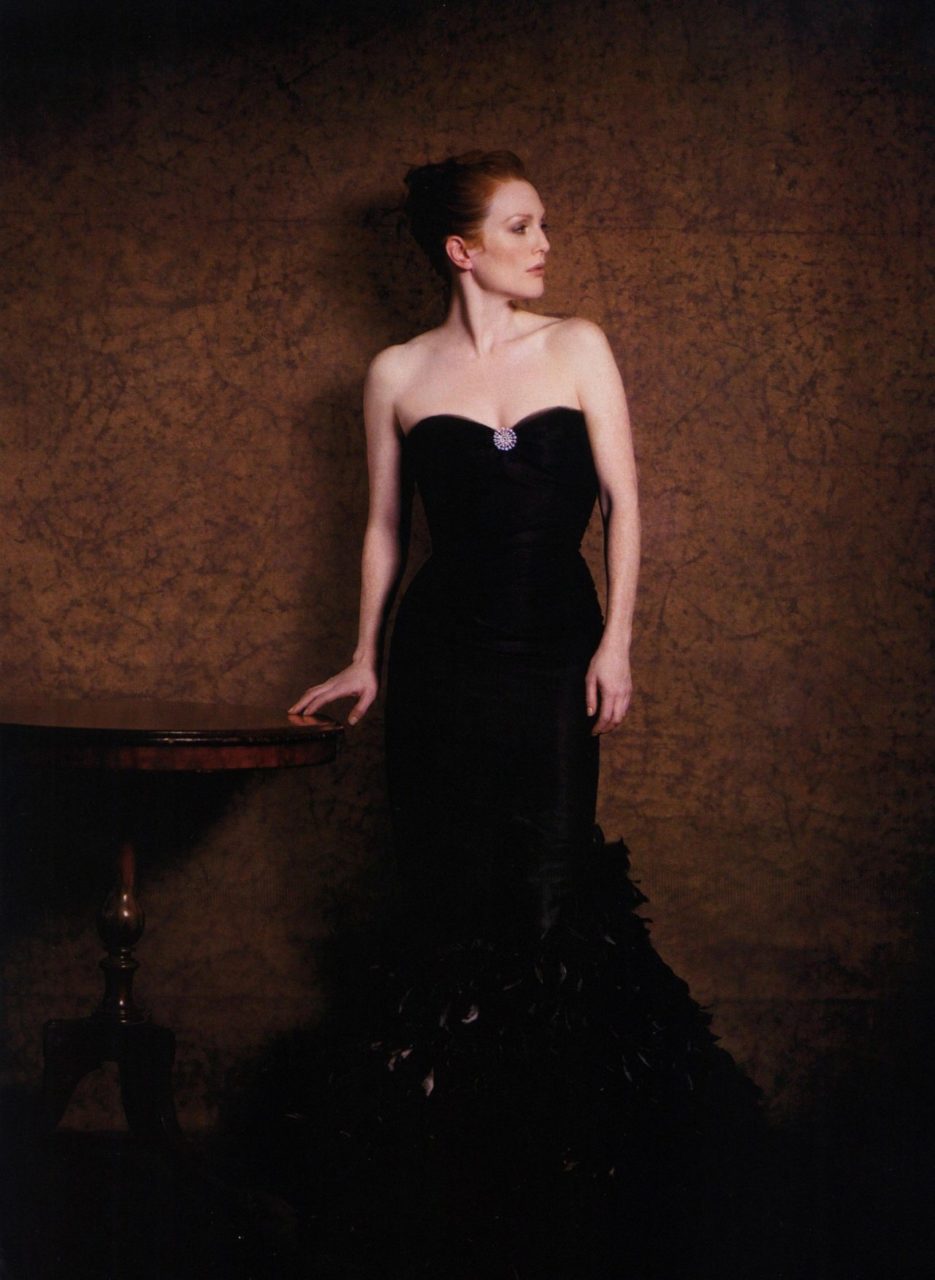

Vogue and Julianne Moore (photographed by Peter Lindbergh in 2008 – Fig. 17) in Harper’s Bazaar. Notably neither version includes the jeweled straps (fallen or otherwise).

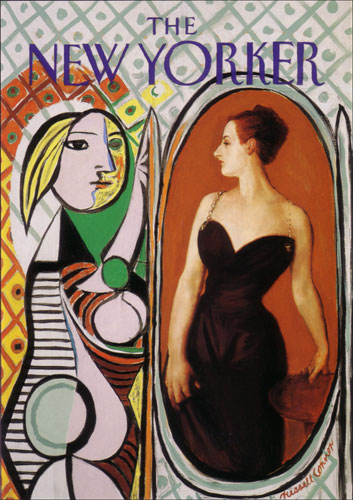

The heart-shaped neckline, small waist, and body-clinging silhouette has been echoed by a number of more contemporary designers, from Olivier Theyskens for Rochas in 2005 (Fig. 18) to Dior dressing Charlize Theron in 2014 for the Oscars (Fig. 19). Moreover, the portrait has frequently appeared in popular culture–for example, facing off against a Picasso on the cover of the New Yorker (Fig. 20).

Fig. 16 - Steven Meisel (American, 1954-). Vogue, "Portraits of a Lady," vol. 189, no. 6 (June 1992): 212. Source: Vogue Archive (subscription required)

Fig. 17 - Peter Lindbergh (German, 1944-). Harper's Bazaar, (May 2008). Source: The Red List

Fig. 18 - Olivier Theyskens (Belgian, 1977-). Rochas, Fall/Winter 2005. Photograph by Lisa Cant at MARILYN/Marcio Madeira. Source: Vogue

Fig. 19 - Raf Simons for Dior (Belgian, 1968-). Charlize Theron, at 2014 Oscars. Photograph by Jordan Strauss, Invision/AP. Source: Epoch Times

Fig. 20 - Russell Connor (American). "Not Myself Today," New Yorker, (November 23, 1992). Source: Russell Connor

Diagram of referenced dress features. Source: Author.

References:

- Davis, Deborah. Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X. New York: Tarcher, 2004.

- Dilberto, Gioia. “Sargent’s Muses: Was Madame X Actually a Mister?” New York Times, May 18, 2003.

- Herdrich, Stephanie L., and H. Barbara Weinberg. “John Singer Sargent in The Metropolitan Museum of Art.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 57, no. 4 (Spring 2000).

- Magali. “La Mode au Théatre.” La Vie Moderne 6 (February 10, 1883): 89.(The translation is my own.)

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau).” Accessed October 3, 2015. http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/12127

- Ormond, Richard, and Elaine Kilmurray. “Madame X or Madame Gautreau.” In John Singer Sargent: The Early Portraits. Complete Paintings, vol. 1, 112-115. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Ormond, Richard. “Sargent, John Singer.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed October 3, 2015, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T076043 (subscription required).

-

Sidlauskas, Susan. “Painting Skin: John Singer Sargent’s ‘Madame X.'” American Art 15, no. 3 (Autumn 2001): 8-33. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109402 (subscription required).

- Venasque, Madame la comtesse de. “La Mode au Théatre.” La Vie Moderne 43 (October 27, 1883): 694. (The translation is my own.)

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “John Singer Sargent (1856–1925)”. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/sarg/hd_sarg.htm (October 2004).