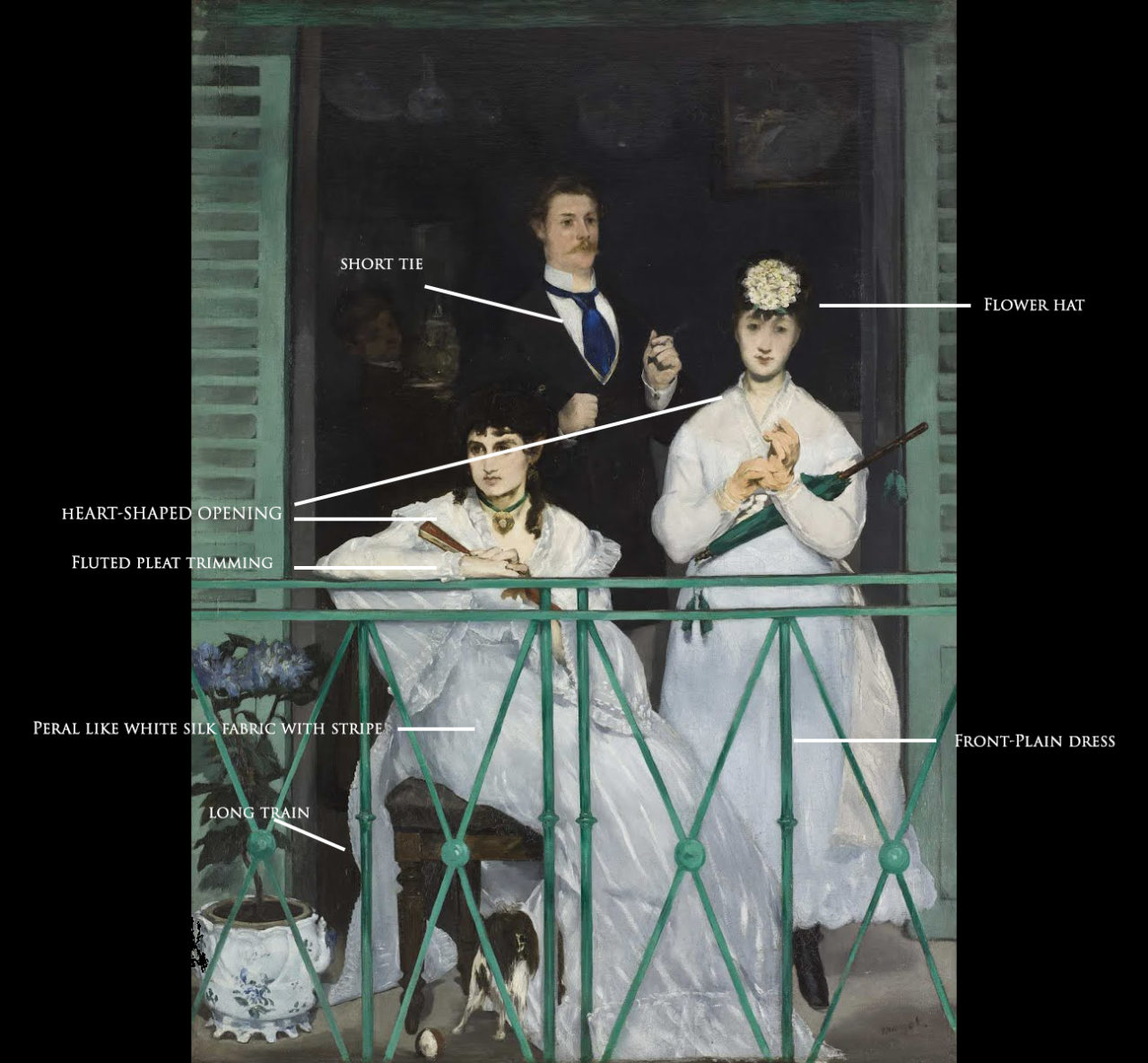

The Balcony is one Édouard Manet’s most popular paintings, but when it debuted it was the subject of much controversy. It is a study in contrasts: shadow and light, color, and types of fashionable dress in the late 1860s.

About the Portrait

É

douard Manet (1832–1883) was a French painter born to a wealthy family. As an artist, he became an important figure in the transition of popular art from Realism to Impressionism.

Manet met fellow artist Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) in the summer of 1868; she posed for Le balcon in September of that same year, along with three others. The Balcony marked a turning point of Manet’s career in which he began to focus on women’s fashion more frequently. With his admirer Émile Zola’s support, Manet became an icon of modernity (Farwell).

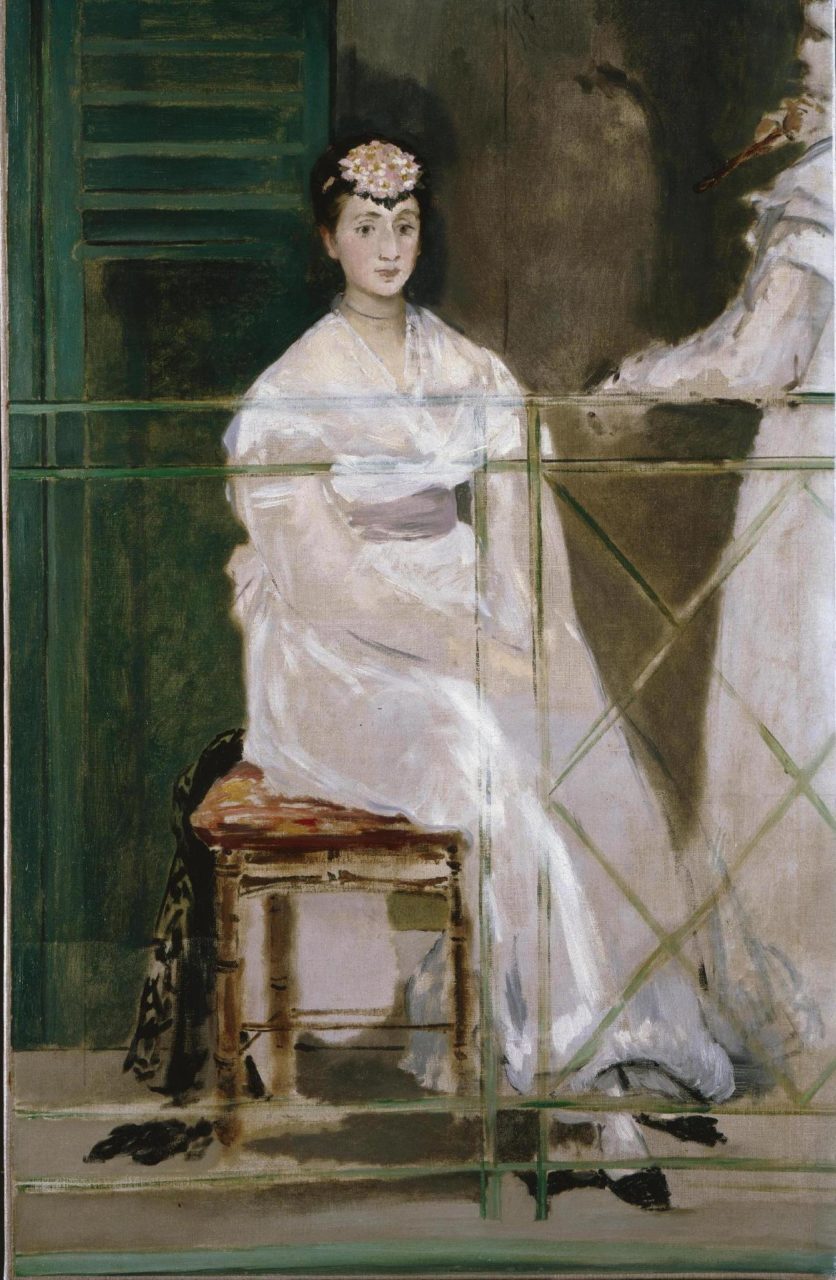

Berthe Morisot (Fig. 1), one of Manet’s favorite models, is seated in the front and wears a sheer white striped gown. The woman standing next to her, also in white, is Fanny Claus (1846-1877), a violinist and friend of his wife. While Morisot seems content to sit and watch the world, Claus seems ready to venture outdoors. The male figure at back in mid-movement is landscape painter Antoine Guillemet (1843-1918). Manet depicted his friends clustered together on a small open balcony painted in green, but there is a strange sense of isolation as none of them are interacting with each other or connected visually (Farwell).

A detail from an earlier sketch of this painting (Fig. 2) shows that several changes were made for the final version. The pink color of Claus’ flower and sash were drained, leaving the women’s palette monochromatic, and Morisot’s and Claus’ positions were swapped.

The painting was directly inspired by Francisco Goya’s Majas on the Balcony (Fig. 3) (Musée d’Orsay). Perhaps Morisot and Claus were transposed in order for Morisot’s dark hair to recall the black veil of the woman at left in Majas.

Le balcon shocked the crowds at the Paris Salon when it was presented in 1869, as they perceived that Manet had prioritized aspects that did not deserve it, and relegated important parts almost to the background, as the Musée d’Orsay explains:

“The vividness of the colours, the green of the balustrade and shutters, the blue of the man’s tie, as well as the brutal contrast between the white dresses and the darkness of the background, were perceived as provocation. The hierarchy usually attached to human figures and objects has been disregarded: the flowers receiving more detail than some of the faces.”

Fig. 1 - Édouard Manet (French, 1832-1883). Berthe Morisot au bouquet de violettes, 1872. Oil on canvas; 55.5 x 40.5 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay, RF 1998 30. Source: MAD

Fig. 2 - Édouard Manet (French, 1832-1883). Fanny Claus, 1868. Oil on canvas; 115.7 x 72.8 cm. University of Oxford - Ashmolean Museum, WA2012.53. Source: Ashmolean

Fig. 3 - Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Spanish, 1746–1828). Majas on a Balcony, ca. 1805. Oil on canvas; 194.9 x 125.7 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.100.10. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. Source: MMA

Édouard Manet ( French 1832-1883). Le balcon (The Balcony), 1868-1869. Oil on canvas, 170 × 124.5 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Image: Musée d’Orsay

About the Fashion

Berthe Morisot is seated in the front, apparently looking down to the street. She is wearing a sheer white striped dress with an open V-shaped neckline and wide pagoda sleeves, trimmed in ruffles of the same fabric. This kind of gown would have been the height of fashionability for hot summer afternoon wear, and Morisot seems to know that she is being appraised while on the balcony. Claus, standing next to her, is also wearing a white dress, but with a strong difference: it is pared down, with narrow sleeves, unpatterned white fabric, and only some frills at the neckline. She cuts a slimmer silhouette, and seems to draw into herself even as she removes her kid gloves. Gloria Groom wrote in Impressionism, Fashion & Modernity (2012):

“Morisot’s relaxed dress with pagoda sleeves suggests an intimate gathering, whereas Claus’s shorter walking dress would usually have been reserved for being out in public.” (158)

The satin stripes on Morisot’s gown were stylish during this time. A gown in figure 4 sports pink satin stripes on a neutral-colored gauze ground. In the April 1869 issue of Peterson’s Magazine, the editor remarks:

“Many striped silks are in the market, as well as others elaborately brocaded with flowers in the natural colors. One silk of exquisite quality is of so light a pearl that it is just “off” a white ground, is brocaded in crocuses of all the natural colors and size.” (328)

The article goes on to discuss bodices (called ‘waists’ or ‘bodies’ at this time):

“Open Bodies, made either square or heart-shaped, will be worn during the warm weather; but there seems to be no decided change in the fashion of making sleeves.” (328)

Trimming is emphasized in the Harper’s Bazar “New York Fashions” column on January 30, 1869, too:

“pleated ruffles are the favorite trimmings. A simple flounce at the edge of the skirt is four inches wide, laid in deep pleats, all turned one way.” (67)

For striped gowns in this era, it is common to see a bias-cut ruffle at the hem – this is visible in figures 4 and 7 – but it is difficult to tell if Morisot’s hem ruffle is similarly cut on the diagonal.

While Claus’ dress is much simpler and more casual, it is fashionably cut and up-to-date. The late 1860s were a time of transition between the crinoline era and the bustle silhouette of the early 1870s. Hemline was a matter of fashion, but was determined by occasion. In Peterson’s Magazine’s “Fashions for August” column in 1869:

“With regard to the make of dresses, we are glad to say that no change has taken place, for so numerous have been the new styles lately, that the fashion would almost change between the time a lady took her dress to her dress-marker and got it sent home. Short dresses for street wear, for both old and young; short dresses for the morning for the young; long dresses for afternoon, or visiting, seems to be the rule.” (157)

While parasols, fans, and gloves were generally fashionable accessories in this era, Claus’ enormous flower is another matter. Small florals were often tucked into hairstyles in the 1860s and 1870s, but statement flowers like this one were less common, especially placed in the middle of the head like hers is. Her flower reads as an artistic statement, perhaps a concession to creativity for her artist friends while her outfit remains plain. Large, central florals like hers were generally seen only on certain occasions; Józefy Neuville, for example, wore a similar bloom in the middle of her hair for a formal portrait in evening dress (Fig. 9). Claus’ flower may be part of a black hat or cap that blends into her hair, but it is difficult to say, and the flower stands out as unusual either way.

Morisot’s visible hairstyle is on-trend, as is her necklace; compare again to Neuville’s portrait (Fig. 9) with its wispy short bangs and ribbon choker.

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à transformation, 1870-72. Gaze de chambéry. Paris: Musée de les arts décoratifs, UF 66-34-3 ABCD. Don Jean-Marie Simon, UFAC, 1966. Source: MAD

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (American). White afternoon dress, ca. 1863. Linen lawn; (b 38", w 28", skirt l 40"-70", in). Augusta Auctions, Lot 69, April 2009, Vintage Fashion and Textile Auction, New York City. Source: Augusta Auctions

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown. Dress, Late 1860s. Cotton and linen, trimmed with lace. London: The John Bright Collection. Source: John Bright

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown. Blue and white striped gauze summer gown, ca. 1870. Gauze and satin. London: Kerry Taylor Auctions, Lot 142, June 10, 2008. Source: Liveauctioneers

Fig. 8 - Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). Madame Théodore Gobillard (Yves Morisot, 1838–1893), 1869. Oil on canvas; 55.2 x 65.1 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.100.45. H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. Source: MMA

Fig. 9 - Jan Mieczkowski (Polish, (1830-1889)). Portret Józefy Neuville, ca. 1871. Albumen print; 10.5 x 6.3 cm. Warsaw: Biblioteka Narodowa (The National Library of Poland), F.572. Source: POLONA

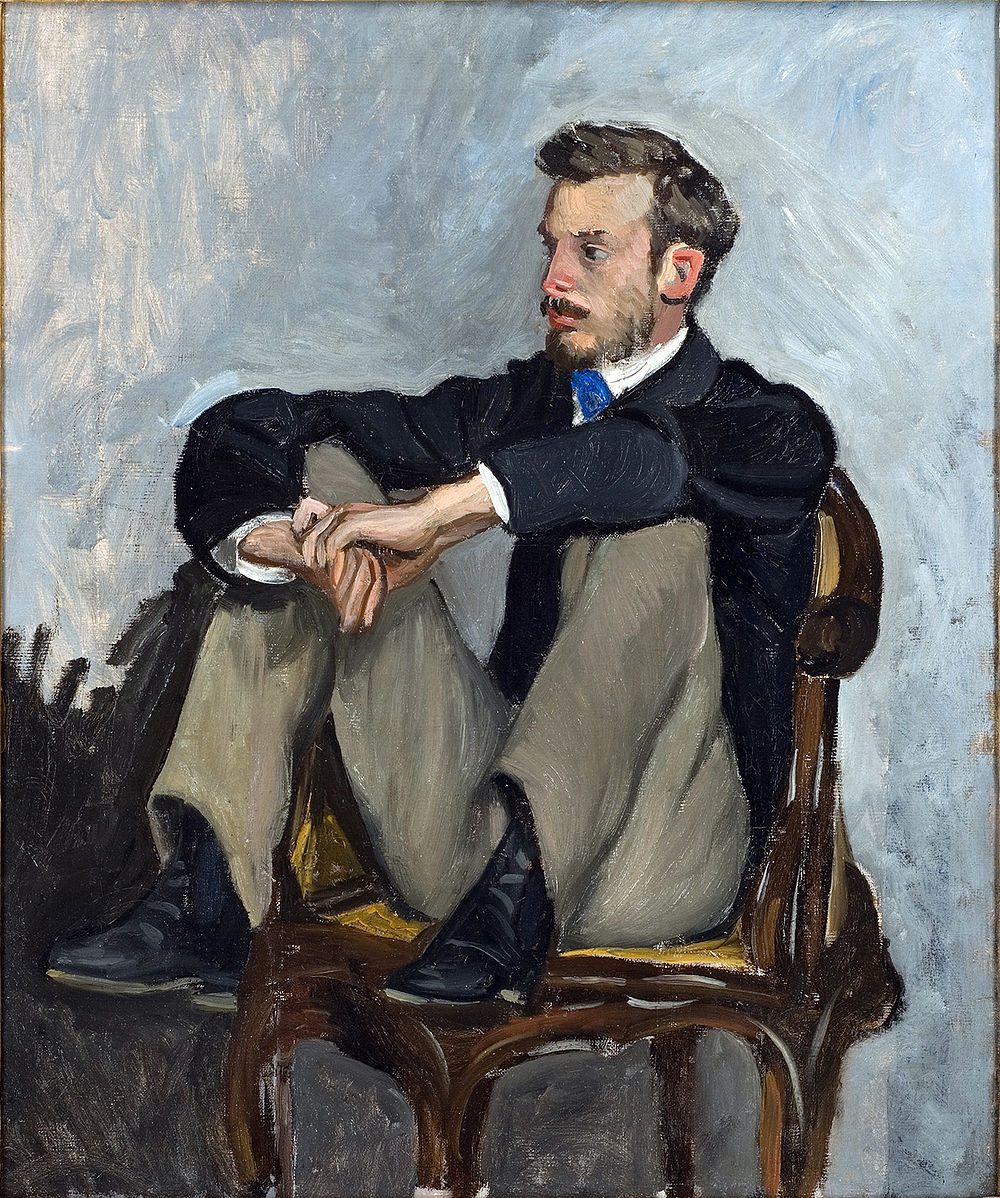

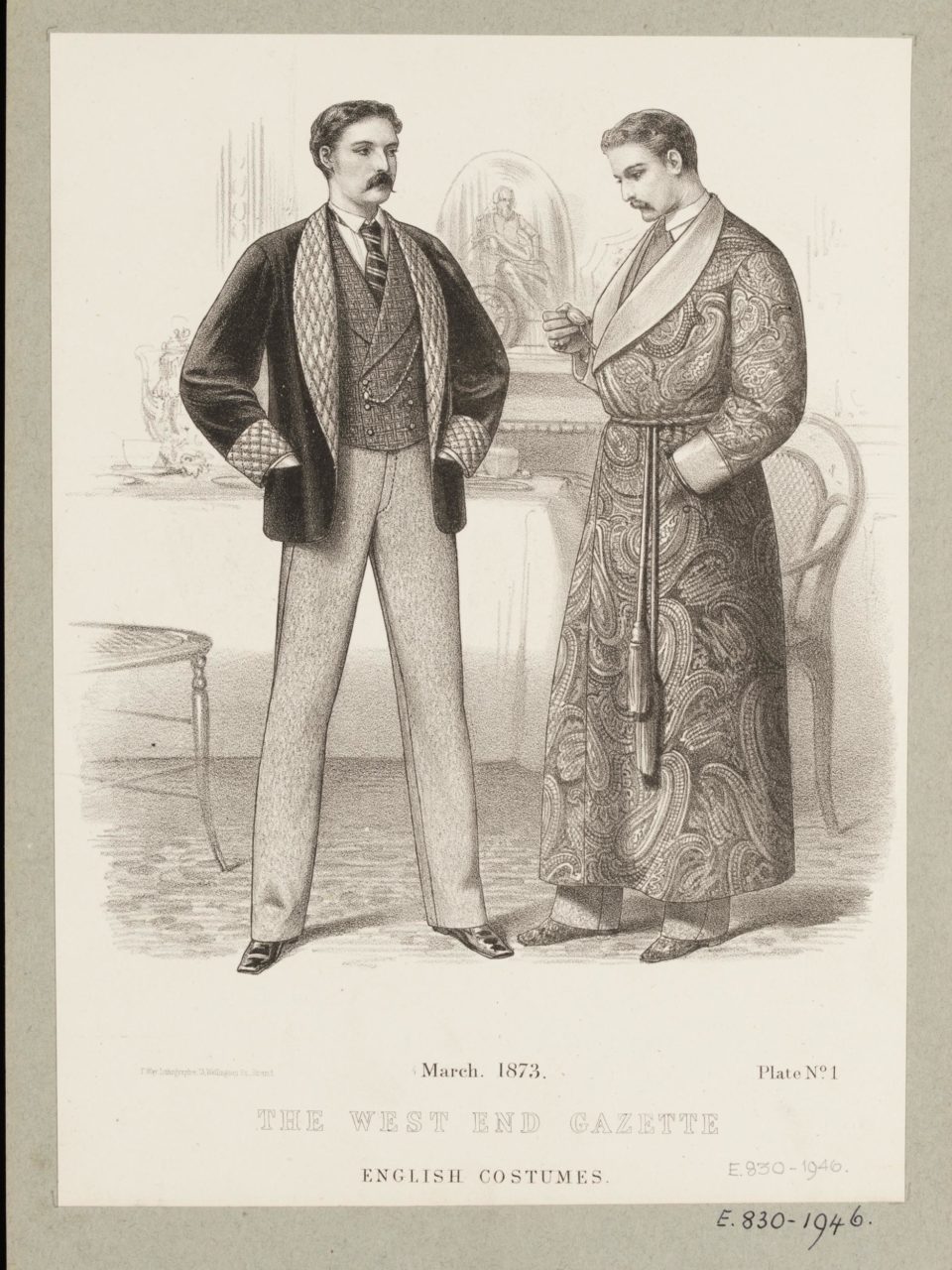

While men’s clothing in this era changed in less noticeable ways than women’s did, there were constant small changes in male dress. Guillemet’s black coat is classic, and unfortunately due to the black background we cannot see any more detail of lapels or construction. But his stock collar and navy blue tie are visible, as are his hairstyle and facial hair. The blue tie may be a nod to a trend, or perhaps a reference to an image like Bazille’s 1867 portrait of fellow Impressionist Renoir, whose blue tie is the only major pop of color in the painting (Fig. 10). Two years earlier than Le balcon, Bazille’s portrait shows Renoir wearing a similarly trim mustache and contrasting dark coat and white collar. His trousers, a light taupe that hardly matches his jacket (or, likely, his hidden waistcoat) demonstrate that men’s clothing did not have to match in color or pattern during this time. Guillemet’s trousers, unseen, may be a similarly contrasting color. Heavy facial hair was still common during this time, so his lack of beard or sideburns stands out just as his cravat (tie) does.

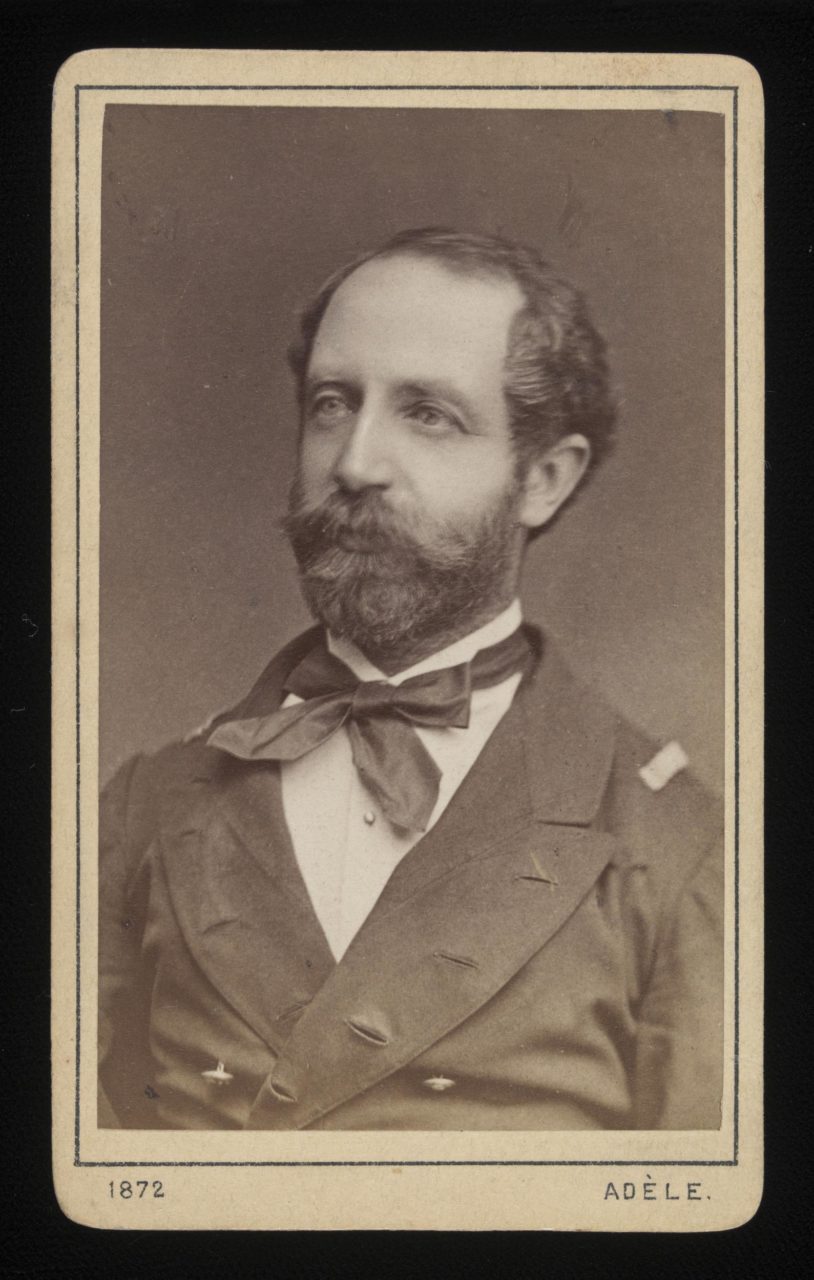

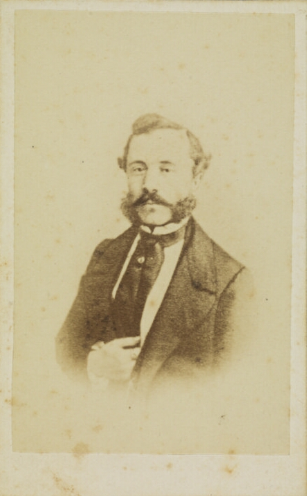

His close-cropped hair matches other images of men during this time (Fig. 11). His tie, left long and loose, is less common but still fashionable. The older style of a cravat can be seen in figure 12, and a more modern tie in figure 13. Many men still chose to tie theirs in a casual bow (Fig. 11).

He is probably wearing a stiff, removable starched cotton or linen collar, which came into use around this time for convenience in washing. While not extravagantly fashionable, Guillamet presents a clean figure with an eye-catching accessory, ensuring that anyone watching from the street comes away with a good impression.

Fig. 10 - Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870). Pierre Auguste Renoir, 1867. Oil on canvas; 61.2 x 50 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay, DL 1970 3, DL 1970 3. Source: MAD

Fig. 11 - Adèle (photographer) (German). Comte de Bombelles, 1872. Albumen photograph mounted onto card; card 105 x 63 mm cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, RPS.1737-2017. Source: VAM

Fig. 12 - Photographer unknown (Polish). Portret Aleksandra Zatwarnickiego, ca. 1865. Odbitka na papierze albuminowym; 8.5 x 5.3 cm. Warsaw: Biblioteka Narodowa, F.40156/W. Source: POLONA

Fig. 13 - Artist unknown (British). Fashion plate, March 1873. Engraving and lithography. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, E.830-1946. Given by Mrs E. M. Bridgland. Source: VAM

References:

- Farwell, Beatrice. “Manet, Edouard.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed May 08, 2017. http://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2150/subscriber/article/grove/art/T053749?q=manet&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit (subscription required)

- “Fashions for April.” Peterson’s Magazine, Vol. 55-56, (April 1869): 328. https://books.google.com/books?id=QJPNAAAAMAAJ

- “Fashions for August.” Peterson’s Magazine 55-56 (August 1869): 157. https://books.google.com/books?id=QJPNAAAAMAAJ

- Groom, Gloria Lynn. “Looking through, across and up.” In Impressionism, Fashion & Modernity. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/816976764

- “Le balcon [The Balcony].” Musée d’Orsay. Accessed 20 April 2020. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/works-in-focus/search/commentaire_id/the-balcony-7199.html

- “New York Fashions.” Harper’s Bazar Vol. II, No. 5 (January 30, 1869): 67. http://hearth.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=hearth;idno=4732809_1443_005