This crinoline-style day dress from 1855 combines decorative elements such as fringe and bold patterns and reflects the rise of voluminous tiered garments, improved cloth printing, and luxurious colors and embellishments utilized during the 1850s.

About the Look

This day dress, designed in 1855, was produced with a combination of silk and wool fabrics. The silhouette can be described as a large, bell-shaped skirt, perhaps supported at the time by a crinoline cage, but more likely by a series of stiffened petticoats. The outspread skirt is contrasted with a loosely fit, pleated bodice, tied at the waist with a ribbon to accentuate the fullness of the garment’s lower half. The fabric is printed with vibrant blue floral, hatching and other small patterns. Details include the delicate lace collar and fringe that trims the pagoda-style sleeves, a signature look of the 1850s (Fig. 1). The Kyoto Costume Institute states in the garment’s description:

“Considering that this mixed fabric of silk and wool is a material hard to print on, this dress with its bright and cheerful colors is a particularly fine example on how much cloth printing techniques had evolved.”

A variety of patterns are printed onto the garment — the repetitive bold floral design evenly spaced on each of the skirt’s tiers being the central focus (Fig. 2). The florals are adorned with a scalloped border, providing the illusion of additional tiers of the skirt. Polka dots cover the space beneath the border and a small criss-cross print overlays both the bodice and the distance in between the floral sections. This delicate criss-cross motif adds to the dress a replication of a woven texture and the sense of added dimension. While unusual and especially attention-grabbing to the modern audience, the use of multiple prints and patterns was common throughout this decade.

Under the flare of the pagoda sleeves, there is a layer composed of faux white sleeves peeking through (Fig. 3) . These sleeves are gathered at the wrists and completed with the same lace that lines the collar and an elegantly-tied blue silk ribbon that matches the one around the waist.

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown (British). Day dress, 1855. Silk and wool. Kyoto, Japan: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC885 78-24-60AB. Source: KCI

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (British). Day dress, 1855. Silk and wool. Kyoto, Japan: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC885 78-24-60AB. Source: KCI

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (British). Day dress, 1855. Silk and wool. Kyoto, Japan: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC885 78-24-60AB. Source: KCI

Designer unknown (British). Day dress, 1855. Silk and wool. Kyoto Costume Institute, AC885 78-24-60AB. Source: KCI

About the context

Throughout the 1850s, sleeve style and construction were one element that was in constant transition. Daniel James Cole and Nancy Deihl write in The History of Modern Fashion (2015):

“Sleeves ranged from the prim straight style of the 1840s to full flared ‘pagoda’ sleeves and many other variations. By the 1850s, engageantes were sometimes quite full and frilled.” (24)

Thid garment features flared pagoda sleeves as well as the mentioned “engageantes,” which are the faux sleeves partially visible underneath the pagoda-style layers. In a similar 1854-1855 print dress from the McCord Museum Collection (Figs. 4-5), the same sleeve style can be observed. As described on the museum’s website:

“During the middle of the decade the pagoda sleeve became quite large, and flounces with bold floral designs, such as those featured here, were popular. Later, geometric designs often found favour, and the pagoda sleeve frequently became even wider.”

This dress is also comparable in color, silhouette, and detailing. It features a circular skirt, draped on top of the cage crinoline, which was invented around this time (Cole and Deihl 24). A pretty blue is used in this design as well, and the garment incorporates a delicate lace around the neckline and a long fringe that lines the edges of the sleeves. A series of complex patterns are printed on the wool fabric, including a bold, floral design outlined with scalloped “frames.”

The McCord Museum analyzes the garment, explaining how:

“The expanding skirt of the 1850s is given buoyancy here by flounces, which also accentuate the breadth of the silhouette. The collarless pointed bodice is basqued (extended below the waist) and features a fringed and flounced three-tier pagoda sleeve embellished by a band of border-printed fabric.”

In a 1855 fashion plate from Les Modes Parisiennes (Fig. 6), a garment closely related to the Kyoto Costume Institute’s day dress can be seen. The light blue and white color palette is used, demonstrating the prevalence and fashionability of these hues especially in regards to fabric printing. Florals decorate each of the skirt flounces, as well as the full, layered sleeves.

An article titled “Paris Fashions for Summer” in the June 1855 issue of The Home Journal includes an excerpt dedicated to flounces, flower patterns, and elaborate fringe trimmings — all of which are notable attributes of the chosen garment. The Home Journal states:

“But when they are garlands of flowers, or sprinkled bouquets, no other shades than those of the flowers are employed. […] Almost all the flounces are trimmed with a fringe.” (1)

Another representation of fashionable dress during this year is shown in the fashion plate from the Journal des demoiselles (Fig. 7). A higher neckline is displayed, similar to the featured garment. A voluminous skirt is also illustrated, accomplished through the layering of petticoats or a crinoline cage. While the fringe lines the tiers of the skirt rather than just the sleeves, it is still noted as a significant addition to clothing during this period.

In a photograph of an unknown woman from 1855 (Fig. 8), similar collar detailing can be identified. The incorporation of fringe trim is continued, decorating the garment’s sleeves and the two-tiered skirt also includes an evenly repeated pattern. Each of these elements resemble that of the featured day dress.

In a November 1855 issue of The New York Times, trends are reviewed, including the variation of flounces that can be seen in different dress styles. For instance, in the garment chosen for analysis, there are only two flounces, whereas a larger number can be observed in some of the comparison pieces or cited fashion plates. The New York Times states:

“Some dresses have flounces of a different color; for instance a barege dress, with six flounces, alternately black and pink. Sometimes, when the flounces are of the same material as the dress, two only are worn; the the upper one very broad, and fastened in at the waist; the lower one a third narrower.” (2)

Another piece from around this period is a wedding dress from 1857 (Fig. 9). Though two years after the blue print dress, this garment still includes fringe trimmings, a high lace collar, and the choice of a light blue color fabric. The color story, full-tiered crinoline silhouette, and stunning trims and embellishments continued to be worn and appreciated throughout the entirety of the decade.

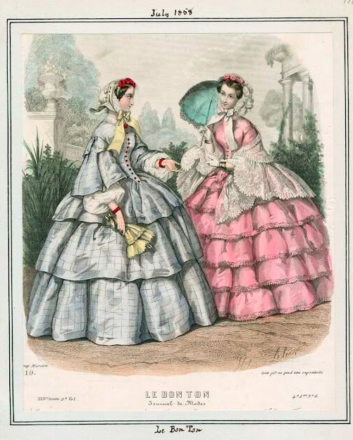

The same can be said of the 1858 fashion plate published by Le Bon Ton (Fig. 10). Design components including flared sleeves, a lace collar, and skirt flounces are still very prominent in trend illustrations for the general public.

These shared design elements in surviving dresses and photographs argue for the fashionability of Kyoto Costume Institute’s silk and wool day dress. Fashion plates from this same year (informing the public on current trends) also display similar colors, trims, shapes and silhouettes — further solidifying its relevancy to trends of the time.

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown. Dress, 1854-1855. Wool mousseline de laine, cotton lining, bone. Montreal: McCord Museum, M973.1.1.1-2. Gift of Mrs. Raymond Caron. Source: McCord Museum

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown. Dress, 1854-1855. Wool mousseline de laine, cotton lining, bone. Montreal: McCord Museum, M973.1.1.1-2. Gift of Mrs. Raymond Caron. Source: McCord Museum

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown. Les Modes Parisiennes, August 1855. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. Journal des demoiselles, 1855-1856. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: The Met

Fig. 8 - Maull & Polyblank. Unknown Woman, 1855. Albumen print; (7 7/8 x 5 3/4 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG P106. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown. Wedding dress, 1857. Barnard Castle: Bowes Museum. Source: Dreamstress

Fig. 10 - Hélöise Leloir (French, 1820–1873). Le Bon Ton, July 1858. Source: Pinterest

References:

- Cole, Daniel James and Nancy Deihl. “1850-1890: The Dawn of Modern Clothing.” In The History of Modern Fashion from 1850. 13-53. London: Laurence King Publishing. 2015. https://www.worldcat.org/title/history-of-modern-fashion-from-1850/oclc/935213653

- “Day Dress.” The Kyoto Costume Institute. Kyoto. Accessed April 13, 2022. https://www.kci.or.jp/en/archives/digital_archives/1850s_1860s/KCI_081

- “Dress.” McCord Museum. Montreal. Accessed March 30, 2022. http://collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca

- “Fashions For November.” New York Daily Times (1851-1857), November 10, 1855. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/european-affairs/docview/95864536/se-2?accountid=27253.

- Scott, Genio C. “Interesting To Ladies: The Gown– Its Past and Present.” The Home Journal, June 9, 1855: 4 https://www.proquest.com/magazines/interesting-ladies/docview/2161729902/se-2?accountid=27253.