Streamlined in shape like other 1930s gowns, the Tears dress features surrealist elements that make it emblematic of the design collaboration between Elsa Schiaparelli and artist Salvador Dalí.

About the Look

T

he Tears dress was part of Elsa Schiaparelli’s Spring 1938 “Circus” Collection, and is considered to be one of her most famous designs. Although rather simple in shape, the garment exhibits elements of Surrealism that would come to define Schiaparelli’s work during this decade. The garment is a floor length, sheath-style, sleeveless dress that is fitted at the waist. The dress extends out into two pointed trains at the back, as if trailing behind the wearer (Fig. 1). It features a wide bateau neckline, and drapes gracefully across the chest to a gathered left shoulder; the opposite side is fastened over the shoulder with a strap. The dress, although an ivory shade now after years of being held in storage, was originally pale blue.

The garment is made from viscose rayon and silk-blend marocain. Made from the same fabric is a gathered veil that falls gracefully from the top of the head (Fig. 2). The fastening of the garment is a zipper made of white plastic—a material new in fashion at the time, and used as both a functional and decorative element by Schiaparelli. Similarly, the use of a viscose rayon material instead of silk—which was the standard in couture—represents her dedication to experimenting with new materials, as opposed to relying on traditional couture textiles.

Fig. 1 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890–1973). The Tears dress, 1938. Rayon, silk. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.393&A,D to F-1974. Given by Miss Ruth Ford. Source: Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 2 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890–1973). The Tears dress, 1938. Rayon, silk. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.393&A,D to F-1974. Given by Miss Ruth Ford. Source: Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 3 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890–1973). The Tears dress, 1938. Rayon, silk. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.393&A,D to F-1974. Given by Miss Ruth Ford. Source: T.393&A,D to F-1974

Beyond its noteworthy innovative use of materials, the garment holds its true significance in its manifestation of the collaboration between Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí. The pattern that repeats throughout the dress features a unique sort of “tear” print that gives the garment its name. The print was designed by none other than Dalí himself. The pink, magenta, and black printed “tears” that cover the dress are then replicated on the veil; however, instead of the flat trompe l’oeil design found on the dress, the veil includes real tears delicately lined with pink and magenta fabric (Fig. 3).

Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890–1973) and Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904–1989). The Tears dress, Spring 1938. Viscose-rayon and silk blend fabric printed with trompe l’oeil print. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.393&A,D to F-1974. Give by Miss Ruth Ford. Source: V&A

About the designer

Although Elsa Schiaparelli is most known for her work created during the 1930s, she got her start in the 1920s with sportswear garments. She created sweaters with two-dimensional collars and bows that were knit into the design (Fig. 4). These garments not only launched her fashion career but illustrated her early adoption of trompe l’oeil design elements. By the mid-1930s Schiaparelli had fully embraced an aesthetic that incorporated Surrealism—the art movement that had been popularized since the 1920s. During this period, she worked with famed Surrealist artists and created some of her most unique and inspired garments (Calahan and Zachary).

Fig. 4 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890–1973). Cravat (Jumper), 1927. Hand-knitted woollen. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.388-1974. Given by the designer. Source: Victoria & Albert Museum

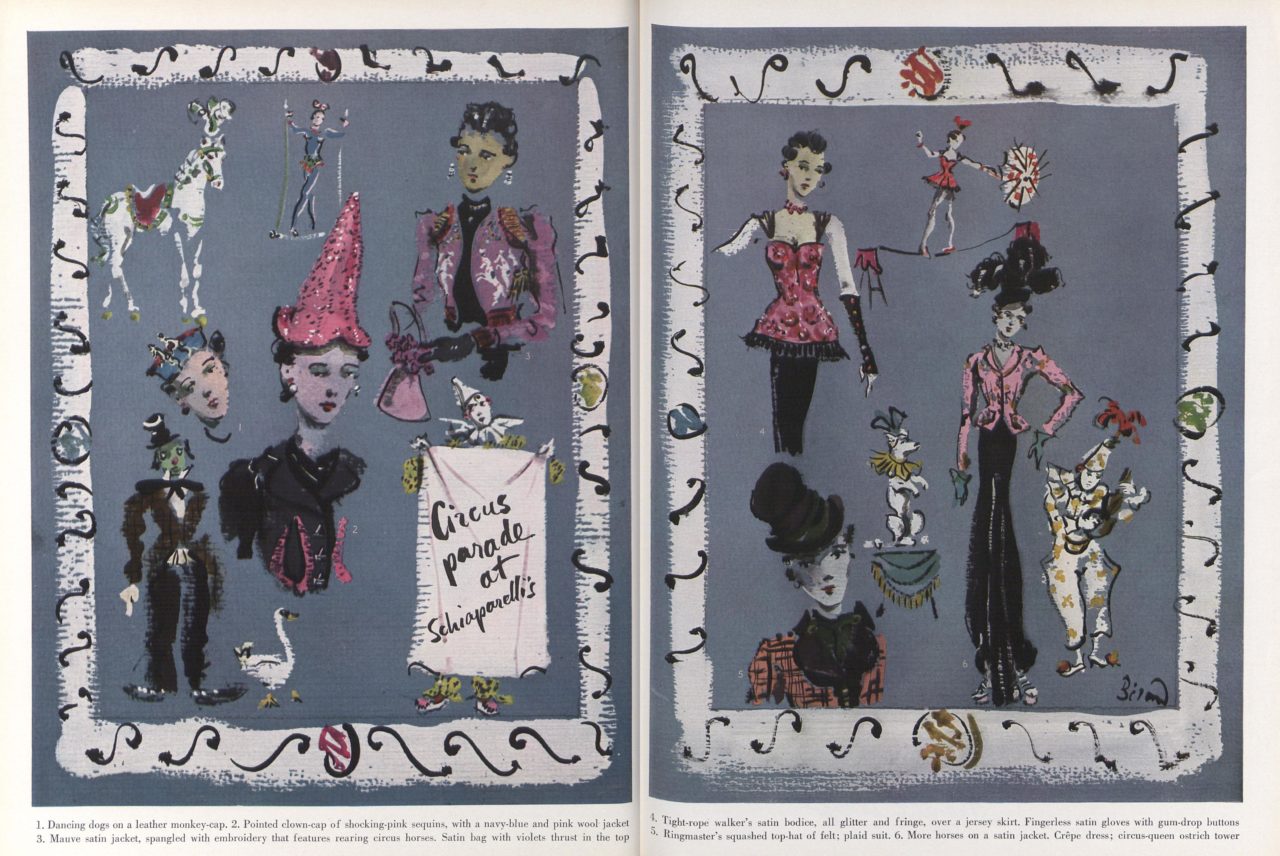

Fig. 5 - Christian Bérard (French, 1902–1949). "Circus parade at Schiaparelli's." Vogue 91, no. 7, (April 1938). New York: Condé Nast Archive. Source: ProQuest

Italian by birth, Schiaparelli set up her base of operations in Paris from 1922 and continued to work there until the political unrest of the late 1930s forced her to leave the city. In the midst of such upheaval, Schiaparelli created one of her most famed collections inspired by the circus. The Circus Collection debuted in the summer of 1938 to great success. According to the Victoria & Albert Museum—which holds multiple pieces from the collection—the Parisian fashion audiences thought it to be the “most riotous and swaggering collection [they’d] ever seen” (Fig. 5).

Schiaparelli’s themed collections set forth a new practice in the creation of fashion. Designing a collection around a specific theme has since become the norm for fashion designers, but at the time, creating a collection with a theme—especially one as whimsical as the circus—was unheard of. Schiaparelli’s work set the standard for “conceptual” collections. She took inspiration from different aspects of art and culture and designed clothing that became progressively more and more eccentric.

Although much of the Circus Collection featured novelty effects and motifs, including prancing horses, performing elephants, acrobats, tents and clowns—the Tears dress is one of the best-known pieces from the collection (“The Tears Dress,” V&A). The garment was designed in collaboration with her dear friend and fellow Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí (Fig. 6).

The dress was donated to the Victoria & Albert Museum by Ruth Ford, who was originally given the piece by Edward James, a patron of Dalí. Ruth Ford was not only a model and an actress, but also the sister of Surrealist poet Charles Henri Ford. She often wore Schiaparelli’s designs, but there are no surviving photographs of her wearing the Tears dress. An article in the 1992 issue of the magazine Harper’s and Queen confirms that it was worn by Ford, as well as others. It was not unusual for famous actresses and socialites of the time to wear even some of Schiaparelli’s more eccentric pieces. For example, such as the famed Lobster dress—another design collaboration with Dalí—was worn by Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor (Fig. 7). Ford’s ownership of the dress represents the way in which Schiaparelli was embedded in the community of Surrealist artists at the time.

Fig. 6 - Photographer unknown. Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí, circa 1949. Fundacio Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres. Source: Salvador Dalí Museum

Fig. 7 - Cecil Beaton (British, 1904–1980). Wallis Simpson photographed for Vogue, 1937. Photograph. Condé Nast Archive. Source: Vogue

About the context

Elsa Schiaparelli was an innovator who created many unique garments, and even helped to introduce her signature color, Shocking Pink, into fashion (Calahan and Zachary). She took inspiration from the world around her, taking art and culture into account when she designed clothes, and the Tears dress was no different. Central to the design of the dress was the influence of Surrealism. The goal of the movement, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was to: “release [the] unbridled imagination” in order to create new and “unexpected” imagery (Voorhies).

Surrealists sought to grapple with the horrors of the First World War, and the turmoil that followed by looking inwards to one’s imagination. One sector of Surrealism that was particularly fantastical was pioneered by artists such as Dalí. The Surrealists had a “disdain for convention” and aimed to create pieces that brought elements from one’s dreams into the visual sphere (Voorhies). Using this movement as a point of inspiration for her designs, Schiaparelli also drew from a wide range of sources such as myth, the constellations, and the circus to create clothing that challenged the norms of couture; her work was truly art in itself (Calahan and Zachary).

In “Fetishizing the Feminine: The Surreal Fashion of Elsa Schiaparelli” Sabina Stent discusses the way in which Schiaparelli was herself a Surrealist artist. Schiaparelli worked with other creatives of the movement, such as Jean Cocteau and Dalí, in order to create her most famous pieces towards the end of the decade; her Skeleton dress (Fig. 8) was also created in 1938. Her collaboration with Dalí did not officially begin until 1936, and The Circus Collection—which included the Tear dress—represented their first official design partnership (Stent 80).

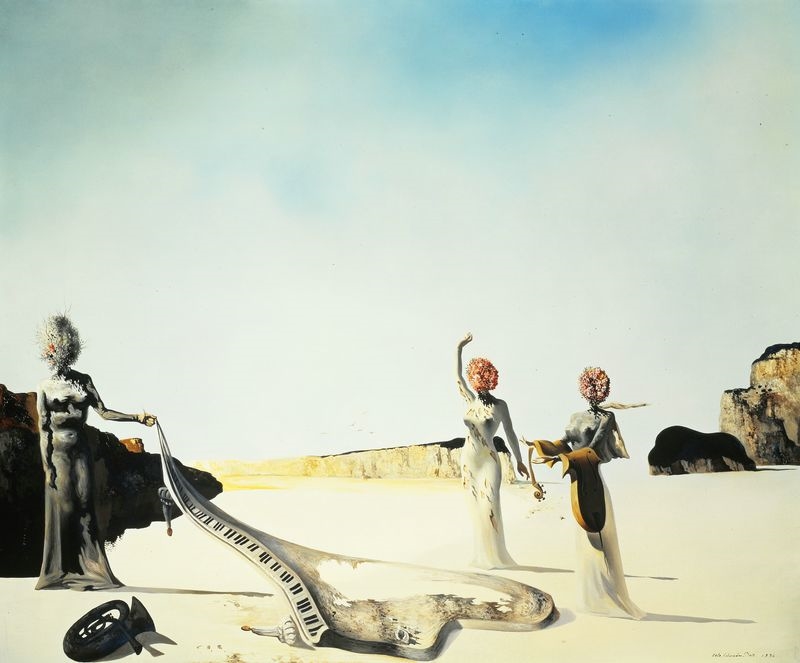

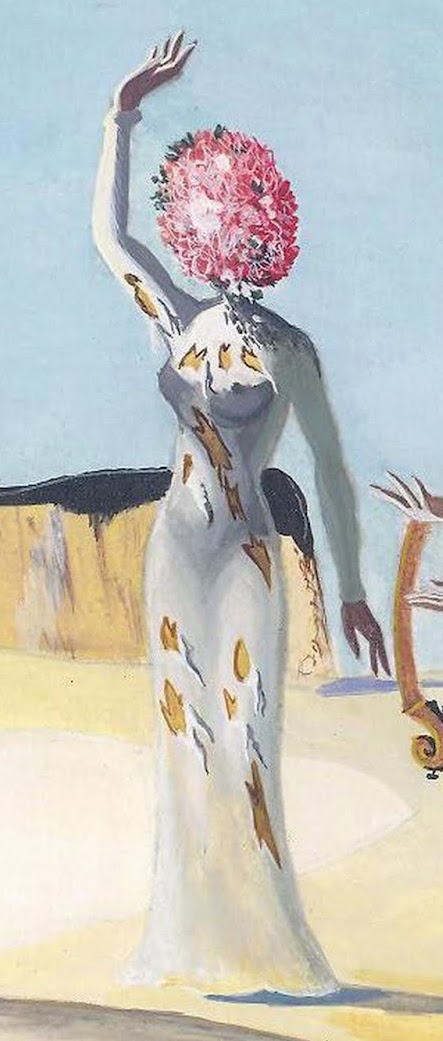

The inspiration for the dress’ “tear” print actually came from an earlier painting by Dalí, titled Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra (Fig. 9). The painting was created between 1934 and 1936, and is the third in a series of paintings—one of which Schiaparelli actually owned. Dalí’s painting exhibits multiple Surrealist elements that were common to the art movement. The painting depicts three women in a barren, deserted landscape with flowers shrouding their faces. Two of them hold instruments, as referenced to the title of the painting; but, it is the third figure in the middle from which the Tear dress takes its inspiration. The middle figure wears what appears to be a white dress (Fig. 10). Upon closer inspection, you can notice that it is the combination of skin and a type of garment that covers the form. The “garment,” which clings to the shape of the figure, appears to be a light color and features rips across the bodice and skirt. In the painting, the tears to the garment resemble flayed skin—an element that Schiaparelli and Dalí turn into something horrifyingly beautiful through the magenta and pink trompe l’oeil print on the Tears dress and the delicately lined tears on the coordinating veil (The Dalí Museum).

Fig. 8 - Elsa Shiaparelli (Italian, 1890–1973). The Skeleton dress, 1938. Silk crêpe, trapunto quilting, cotton wadding. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.394&A-1974. Given by Miss Ruth Ford. Source: Victoria & Albert Museum

Fig. 9 - Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904–1989). Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra, 1936. Oil on canvas; (21 3/4 in x 25 5/8 in). St. Petersburg, FL: Salvador Dalí Museum, 2000.24. The Dalí Museum, Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. Source: Salvador Dalí Museum

Fig. 10 - Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904–1989). Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra (detail), 1936. Oil on canvas; (21 3/4 in x 25 5/8 in). St. Petersburg, FL: Salvador Dalí Museum, 2000.24. The Dalí Museum, Gift of A. Reynolds & Eleanor Morse. Source: Salvador Dalí Museum

Its Afterlife

T

he Tears dress marks one of the first official collaborations between a fashion designer and a well-known artist. Since then, many designers have turned to the art world as a source of inspiration and sought to collaborate with artists. Similarly, the garment was part of a themed collection that was itself highly influential to the world of haute couture, and eventually the fashion industry as a whole. Now it has become standard to create conceptual collections each season and that concept in and of itself can be traced back to Schiaparelli. Many designers in the 20th and 21st centuries take inspiration from the work of Schiaparelli, and show that although form can be restrained, unusual design elements can be incorporated to create true pieces of clothing art (Calahan and Zachary).

In recent years, the house of Schiaparelli has been revived and the new designers have looked to Schiaparelli’s most famous work from the 1930s as a source of inspiration. For the Spring 2016 collection, artistic director Bertrand Guyon seemed to favor a simple silhouette for the patterned dresses, making the whimsical prints the focus—which is in line with the design of the Tears dress (Fig. 11). In Spring 2019, Guyon designed a ready-to-wear line for the house that was an homage to the collaborations between Schiaparelli and various Surrealist artists. The direct references to Surrealist artworks in the collection’s design and marketing is reminiscent of the collaborative effort that made pieces like the Tears dress so special (Fig. 12). Design elements that are reminiscent of the Tears dress pattern can be seen in a later ready-to-wear collection by Daniel Roseberry. For Spring 2020, he created an ensemble in which a snakeskin-patterned dress has holes cut throughout, revealing a layer of floral print beneath it (Fig. 13). Playing with elements of Surrealism to create eye-catching clothing, as Schiaparelli did for the Tears dress, is therefore still central to the Schiaparelli brand.

Fig. 11 - Bertrand Guyon for Schiaparelli (French). Look 19, Spring 2016 Couture. Photo by Kim Weston Arnold. Source: Vogue

Fig. 12 - Bertrand Guyon for Schiaparelli (French). Look 11, Spring 2019 Ready-to-Wear. Photo courtesy of Schiaparelli. Source: Vogue

Fig. 13 - Daniel Roseberry for Schiaparelli (American). Look 1, Spring 2020 Ready-to-Wear. Photo courtesy of Schiaparelli. Source: Vogue

References:

- Calahan, April and Zachary, Cassidy. “Elsa Schiaparelli.” Dressed, iHeart Radio, May 8th, 2018, https://www.iheart.com/podcast/105-dressed-the-history-of-fas-29000690/episode/elsa-schiaparelli-29294434/.

- Etherington-Smith, Meredith. “Q: How Many Surrealists does it Take to Change Haute Couture?: A: A Lobster.” Harpers and Queen (Nov. 1992): 154-155, 214. ProQuest, https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2020141448?accountid=27253 .

- “Fetishizing the Feminine: The Surreal Fashion of Elsa Schiaparelli.” Nottingham French Studies, vol. 50, no. 3 (Oct. 2011): 78–87. EBSCOhost, doi:10.3366/nfs.2011-3.006.

- “The Circus Collection: Elsa Schiaparelli.” Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O15665/the-circus-collection-evening-ensemble-elsa-schiaparelli/

- “The Tears Dress: Elsa Schiaparelli.” Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O84418/the-tears-dress-evening-ensemble-dress-elsa-schiaparelli/.

- “Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in Their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra.” The Dalí Museum, https://archive.thedali.org/mwebcgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=112;type=101

- Voorhies, James. “Surrealism.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/surr/hd_surr.htm